Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111869

Revised: July 30, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 187 Days and 15.8 Hours

Liver transplantation is a life-saving procedure for patients with end-stage liver diseases and acute liver failure. With advances in surgical techniques and immu

Core Tip: Liver transplant recipients are at risk of various ophthalmic complications, both infectious and non-infectious due to immunosuppression and drug toxicity. Infectious complications from pathogens like cytomegalovirus, Herpes simplex virus, Candida and Aspergillus require prompt diagnosis and treatment to preserve vision. Non-infectious manifestations include retinal vascular changes, cataracts, dry eye disease and neoplasms like post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders. Early recognition, vigilant monitoring and management are essential to improve patient outcomes in this population.

- Citation: Kaur M, Arora J, Naseem M, Singh A, Kumar V, Sohal A. Ocular complications after liver transplantation: A comprehensive review of infectious and non-infectious etiologies. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 111869

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/111869.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111869

Liver transplantation represents the definitive treatment modality for a range of acute and chronic hepatic disorders. According to data from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN), the number of liver transplants performed in the United States in 2023 reached a record high, totaling 10659 procedures[1]. With advancements in surgical technique and immunosuppressive regimens, there has been improvement in both graft and patient survival rates. According to the OPTN data, the overall patient survival rate is 93.5% at 1 year following deceased donor liver transplant and 81% at 5 years[1]. With these increasing success rates, the focus has expanded to include quality of life issues, such as visual health and the alleviation of medical complications that can impact outcomes.

Ocular complications in liver transplant patients may result from several interrelated pathophysiological mechanisms. Prolonged immunosuppression increases susceptibility to opportunistic infections, drugs such as cyclosporine and tacrolimus, which are commonly used to prevent graft rejection can cause optic neurotoxicity. Pre-existing systemic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes mellitus may be exacerbated post-transplant leading to compromise of retinal microvasculature. This review aims to highlight the spectrum of ocular complications associated with hepatic transplantation, outline preventive strategies and discuss current approaches to their management.

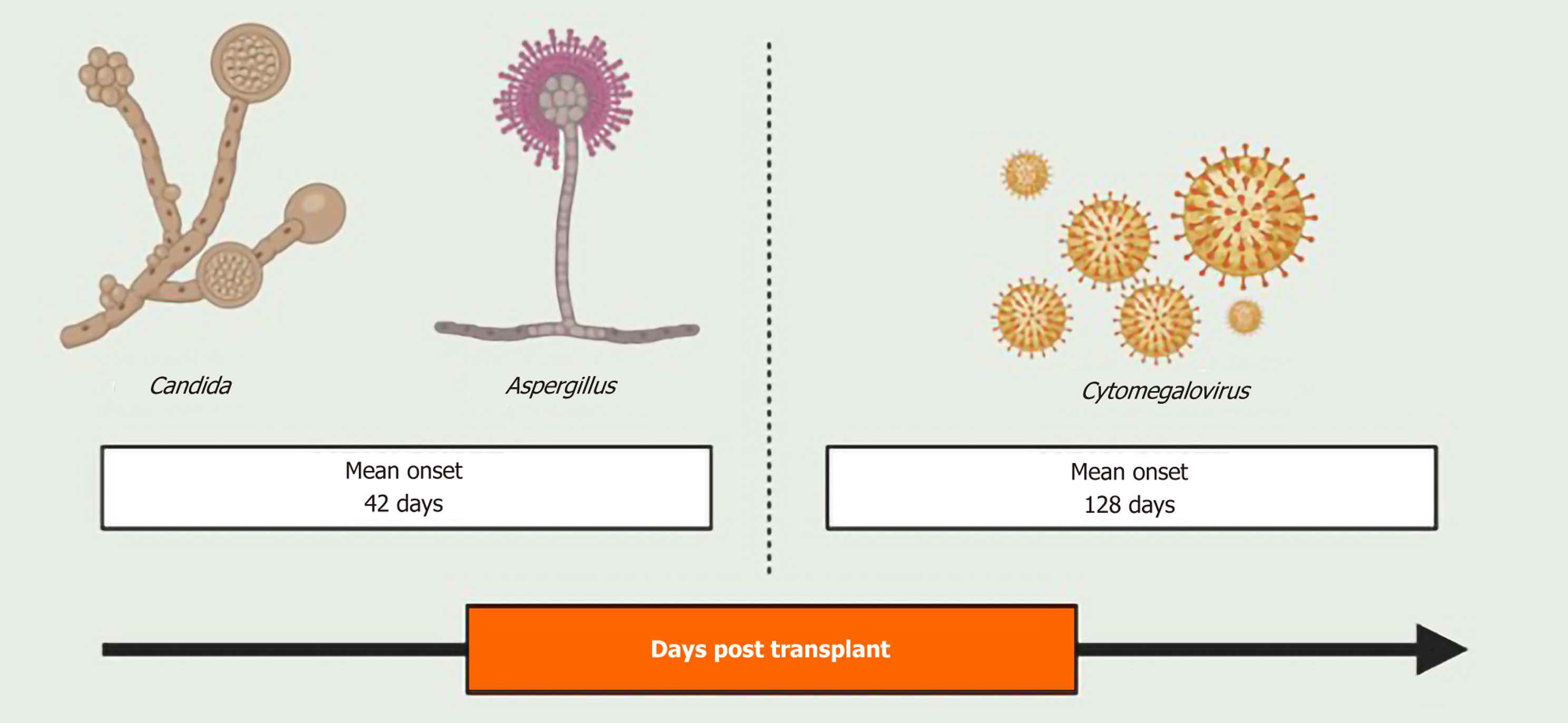

Infectious ocular complications, though relatively rare, have been reported after solid organ transplant with incidence following kidney, heart, and bone marrow transplantations reported between 2%-5%[2-4]. In a study by Papanicolaou et al[5] involving 684 orthotopic liver transplant recipients, the incidence of ocular infections was reported to be 1.3%. Immunosuppression in these patients predisposes them to opportunistic infection, with cytomegalovirus being the most common viral pathogen, and Candida and Aspergillus representing the most frequent fungal organisms. Notably, fungal infections tend to occur earlier in the post-transplantation period, with a mean onset of 42 days post-transplant, compared to viral infections, which typically present around a mean of 128 days[5] (Figure 1). The retina is the commonly involved ocular structure, affected either as an isolated opportunistic infection or as part of disseminated systemic infection[5]. Table 1 provides a summary of the infectious ocular complications post-liver transplant.

| Infection type | Pathogen(s) | Typical clinical features | Diagnostic method | Treatment |

| CMV retinitis | Cytomegalovirus | Retinal hemorrhage, necrosis | Fundoscopy, PCR | Valganciclovir, ganciclovir |

| Herpetic keratitis | HSV-1, HSV-2 | Dendritic corneal ulcer | Slit-lamp, PCR | Acyclovir, foscarnet |

| Herpes zoster ophthalmicus | Varicella zoster virus | Pseudodendritic, periocular pustular skin eruption | Slit-lamp, PCR | Acyclovir, famciclovir, valacyclovir |

| Candida endophthalmitis, Candida retinitis | Candida spp. | Endophthalmitis Retinitis: Creamy raised retinal lesions | Slit-lamp, Fundus exam, PCR | Fluconazole, voriconazole, intravitreal amphotericin B |

| Aspergillus endophthalmitis | Aspergillus species, Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus terreus | Corneal ulcer, satellite lesions, fluffy white-pre-retinal lesions | Fundoscopy | Voriconazole, amphotericin B |

| Rhino-orbital cerebral zygomycosis | Rhizopus, Mucor, Absidia | Diplopia, Ptosis, ophthalmoplegia, decreased visual acuity, blindness | MRI/CT, PCR | Amphotericin B, debridement |

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis is one of the most common ocular infections in immunosuppressed patients and CMV is the most common infectious pathogen in liver transplant patients[5-7]. Literature has stressed the utility of differentiating between CMV infection and CMV disease when making therapeutic decisions. While CMV infection refers to the detection of viral presence through laboratory methods, CMV disease requires the presence of accompanying clinical signs and symptoms attributable to the virus, warranting medical intervention[8].

Prophylactic antiviral regimens during immunosuppressive periods have postponed the development of CMV disease. However, delayed CMV continues to be a significant cause of morbidity[9]. The retina is typically the primary ocular site affected, with retinal lesions often beginning in the periphery- initially asymptomatic- before progressing centrally and threatening vision. In transplant recipients, CMV disease most commonly occurs within the first post-transplant transplant as part of disseminated infection. In the late post-transplant period, it often presents as an isolated ocular infection without another concomitant clinical manifestation[10]. Several studies report that upto 50%-60% of patients can be asymptomatic at diagnosis[11,12]. CMV retinitis is primarily a clinical diagnosis based on the characteristic fundus findings. In transplant patients, the appearance of CMV retinitis is typical, with characteristic vessel sheathing, edematous and hemorrhagic lesions with actively extending borders, and a pallid necrotic center[13,14]. However, atypical cases may resemble retinitis caused by herpes simplex virus (HSV) or varicella zoster virus (VZV), creating diagnostic uncertainty. A CMV-QNAT on a vitreous fluid, biopsy, or vitrectomy sample can be helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Standard CMV prophylaxis regimens include IV ganciclovir and/or oral valganciclovir, typically administered for 12 weeks to cover the period of maximal immunosuppression[15,16]. While this remains standard practice, emerging data suggest that prolonged prophylaxis may be safer and more effective in select high-risk populations[17]. Post-transplant protocols typically involve periodic monitoring for CMV viremia[18].

Management strategies are tailored based on disease severity and patterns of resistance[18].

For initial episode of CMV disease, Oral Valganciclovir 900 mg twice daily (Patients who can tolerate and adhere) or IV ganciclovir (5 mg/kg every 12 hours) is recommended as the first-line treatment in adults with normal kidney function.

During treatment, renal function and CMV viral load should be monitored weekly. Nonnormalized glomerular filtration rate, such as Cockcroft-Gault formula i.e., mL/minutes is recommended to guide dosage adjustments.

In severe disease, cases with persistent high viral loads or leukopenia, dose reduction of immunosuppressive therapy should be considered.

Foscarnet is reserved for ganciclovir-resistant cases. Resistance to both oral ganciclovir and intravitreal foscarnet can be treated by the addition of leflunomide[19].

An important consideration is the systemic toxicity associated with ganciclovir and foscarnet, which may necessitate intravitreal drug delivery augmented with systemic therapy as tolerated. A Multidisciplinary approach is essential for optimal management[20]. Currently, no universal guidelines exist regarding the preferred route of administration.

Following treatment, patients require vigilant surveillance for CMV reactivation, given the risk of recurrence, esp

Herpetic keratitis is a viral infection of the cornea caused by HSV. Following primary infection, HSV remains latent in the trigeminal ganglion and carries a risk of reactivation, particularly in the immunosuppressed population. Transplant recipients are at an increased risk of reactivation during the first month after surgery[21]. While primary transmission from an allograft is rare, isolated cases have been reported[22,23].

Patients present with redness, pain, irritation, photophobia and increased tearing. The symptoms can closely resemble other infectious keratitis such as those caused by VZV, adenovirus, enterovirus and fungi. Diagnosis is made by identi

Prevention strategies- HSV IgG status of the recipient should be tested prior to transplantation. Seropositive patients carry a higher risk of reactivation if they are not receiving prophylaxis. Ganciclovir, acyclovir, valacyclovir and valgan

VZV can present as herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO) in immunocompromised patients. Like HSV, VZV has the tendency to remain latent in nerve ganglia and immunosuppression promotes its reactivation[27]. HZO occurs when the virus gets reactivated in the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve[28]. It has been reported that older transplant recipients are at greater risk of developing HZO[29]. The most common presentation is keratitis, followed by uveitis, conjunctivitis, and retinitis.

HZO can present as a pustular skin rash on the eyelid known as Periocular pustular skin eruptions which usually crusts after 7 days to 10 days[28]. It usually presents as punctate keratitis with a pseudo dendritic pattern, which looks similar to HSV keratitis[28]. Nucleic Acid Amplification Test can be used to distinguish between two entities[27]. Disciform keratitis and Acute Retinal Necrosis are the other forms in which it can present. Disciform keratitis presents with raised intraocular pressure and large circular corneal opacification due to corneal neovascularization[28]. Severe cases can eventually lead to corneal scarring and perforation[27,30]. Acute retinal necrosis or progressive outer retinal necrosis involves necrotic inflammation of the retina, often painless and more rapid than that in immunocompetent patients, with the potential to cause permanent vision loss

Management- HZO should be considered in post-transplant patients who present with complaints such as blurring of vision, headache or pustular skin eruptions. All patients with suspected HZO should undergo thorough and urgent ophthalmic examination starting with the eyelids, conjunctiva and cornea. Detailed fundoscopic examination should also be performed along with the measurement of intraocular pressure[28]. Treatment for HZO is recommended to be started within 72 hours of the symptom onset to prevent post-herpetic neuralgia[28]. Intravenous Acyclovir therapy 800 mg 5 times a day for 7 days to 10 days is usually recommended for the treatment of HZO, but it can be extended in post-transplant patients because VZV DNA is shown to persist for longer durations in immunocompromised patients[31]. Some studies have shown Famciclovir 500 mg 3 times a day and Valacyclovir 1 g 3 times a day to be as effective as Acyclovir 800 mg 5 times a day[28].

Pre-transplant prophylaxis: The patients undergoing liver transplant should undergo pre-transplant serological testing for VZV. The potential transplant patients should be vaccinated 2 weeks to 4 weeks prior to the scheduled transplant with two doses of live attenuated varicella vaccine[29].

Post-transplant prophylaxis: The HZ vaccine is contraindicated in transplant patients, because it carries the risk for disseminated disease in the setting of immunosuppression[31]. Acyclovir, famciclovir and valacyclovir can be used as short-term prophylaxis in liver transplant patients, in case CMV prophylaxis is not already being provided[31,32].

Endophthalmitis refers to infection of the aqueous or vitreous humor, which can lead to permanent vision loss within days of symptom onset[33]. It has been noted that the prevalence of fungal endophthalmitis is significantly lower than bacterial endophthalmitis[34]. Fungal endophthalmitis is rare and usually occurs secondary to invasive fungal infection (IFI), which is one of the most important complications in liver transplant patients[35]. The incidence of IFI in in these patients is reported between 5% and 42%[36]. Patients with underlying liver disease have been linked to increased incidence of several fungal infections, such as Candida, which, when combined with immunosuppression post-transplant, can result in worse outcomes[35,37].

Candida: Candida eye infections can present both as endophthalmitis or retinitis, usually secondary to candidemia, which is disseminated candida infection. Candidemia in transplant and immunocompromised patients is usually secondary to infected wounds or intravenous catheters[38]. It can present as:

Candidal endophthalmitis: Patients usually report symptoms such as pain, blurring of vision, or spots in the visual field[39]. These symptoms, especially in the setting of disseminated disease, warrant a thorough eye examination[38].

Candidal retinitis: Fundus examination in these patients is characterized by multiple, small, creamy, raised retinal lesions, which can extend into the vitreous cavity and form white floating colonies[40].

The diagnosis is usually established by correlating clinical findings with positive blood cultures in disseminated disease. Negative blood cultures might need vitreous humor aspiration and PCR testing for the detection of the causative organism[33,41]. It has been observed that Candida albicans is the most common pathogen involved[42]. Ocular coherence tomography imaging can also be used for retinal lesions, which can demonstrate the involvement of different retinal layers.

Management of Candida eye infections usually begins by removing all intravascular catheters and conducting a thorough eye examination[43]. Although amphotericin B has been considered the gold standard for treating Candidemia, it has poor ocular penetrance and is toxic[40,44]. However, liposomal amphotericin B has better ocular penetrance[45]. For patients with retinitis and endophthalmitis without significant vitreous involvement, first and second-generation antifungals, Fluconazole and Voriconazole respectively, can be used for 2 weeks to 4 weeks.

Voriconazole is usually given as 400 mg BID for two doses loading dose, then 300 mg/day if given intravenously or 200 mg BID/ day if given orally[45].

Fluconazole is usually given as an 800 mg loading dose and then 400-800 mg/day either orally or intravenously[45].

For significant vitreous involvement, intravitreous injections of amphotericin B and Voriconazole, along with pars plana vitrectomy, are generally recommended[40,46].

For intra-vitreous injection, Voriconazole is usually given at 100 µg/0.1 mL, and amphotericin B is given at 5-10 µg/0.1 mL[45]. They can also be repeated after 48-72 hours, depending on the clinical course[47].

A case report by Varma et al[40] documented deterioration of symptoms in a patient with candidal retinitis despite using intravenous Fluconazole. They then switched to Voriconazole 4 mg/kg body weight, which showed significant resolution of lesions after 2 weeks.

Aspergillus: Liver transplant patients are very susceptible to both invasive aspergillosis as well as Aspergillus endophthalmitis[31]. The most common causative Aspergillus species are Aspergillus fumigatus 73%, Aspergillus flavus 14%, and Aspergillus terreus 8%[39]. A study conducted by Hunt et al[48] reviewed the autopsy reports of 85 liver transplant patients, out of which 7 (7.1%) were found to have Aspergillus endophthalmitis. It was also noted that although in these patients, the eyes were the second most common organ affected by Aspergillus, yet only one patient was correctly diagnosed before death. The patients with early-onset Aspergillus endophthalmitis after transplant less than 25 days, or multi-organ involvement are considered to have poorer outcomes[39].

Aspergillus eye infections can present as dacryocystitis, conjunctivitis, ulcerative keratitis, uveitis, vitritis, endophthalmitis or necrotizing scleritis[49]. The symptoms include hyperemia, tearing, to pain on eye movement, and blurring of vision. Aspergillus endophthalmitis is usually bilateral, begins posteriorly in the choroid or retina, and frequently has vitreous involvement[48]. But the course remains more sub-acute when compared to bacterial or viral endophthalmitis[33]. Slit lamp examination for corneal involvement shows corneal ulcers, hypopyon, and satellite lesions[49]. Fun

A few studies have also shown that due to the preference for macular involvement in Aspergillus endophthalmitis, it is associated with poorer visual outcomes compared to other causes of fungal endophthalmitis[50]. Amphotericin B is commonly used to treat both invasive aspergillosis and Aspergillus endophthalmitis, but it has poor ocular penetrance[49]. The use of second-generation antifungal drugs such as voriconazole has been associated with improved outcomes[39]. In patients with vitreous involvement, intravitreous injections of amphotericin B 5 mg/0.1 mL or voriconazole 100 µg/0.1 mL are also recommended, along with para-plana vitrectomy[33]. If the general condition of the patient permits, the combined use of intra-vitreous antifungal injections and prompt vitrectomy is associated with better visual outcomes in these patients[49].

Rhino-orbital cerebral zygomycosis: This necrotizing infection, mainly caused by Rhizopus, Mucor, and Absidia species, is a devastating complication of immunosuppression in transplant patients[41]. The ocular symptoms can range from diplopia, ptosis, and ophthalmoplegia to decreased visual acuity and blindness[41,51]. Blindness can be secondary to central retinal artery occlusion[52], optic nerve infarction[53], or infarction of the optic chiasm[41,54]. A case report by Sabhapandit et al[55] documented similar symptoms in a 42-year-old post-liver transplant patient on postoperative day 20. They concluded that long hospital stay post-transplant is associated with high zygomycosis incidence[55].

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography imaging of the affected areas are useful in assessing the spread of the disease[51]. The patients affected with zygomycosis are documented to have imaging findings such as thickening of the medial rectus and superior oblique muscles with fat stranding or contiguous areas of non-enhancing tissue in the paranasal sinuses, suggestive of angioinvasive infection[55]. The diagnosis can also be supplemented by using a pan-fungal qualitative PCR assay for markers such as Mucorales deoxyribonucleic acid, which are specific for invasive zygomycosis[51,55]. On histologic evaluation of the affected tissue, wide, sparsely septate ribbon-like hyphae are usually present[56].

Amphotericin B and liposomal amphotericin B are the key treatments for zygomycosis[56]. But the successful treatment in liver transplant patients requires a multifaceted approach- reduction of immunosuppression, systemic antifungal therapy, surgical debridement of the affected tissue, and even local irrigation using antifungal drugs such as amphotericin B[36,57].

The overall mortality for Rhino-orbital cerebral zygomycosis in transplant patients has been reported as around 52.3%[21,56]. Osseis et al[58] described a case series of two liver transplant patients who were diagnosed with zygomycosis within 15 days of transplant receipt. Even with adequate treatment, both patients died within 10 days after the diagnosis, highlighting the severity of the disease. Another case report showed that the transplant patients who had aggressive reduction or complete discontinuation of immunosuppression had improved survival compared to those with no change in their regimen (69.5% vs 46.1%, P = 0.05)[57].

Toxoplasma gondii (T. gondii) has been reported to cause ocular infection in post-transplant patients[58,59]. Traditionally, the diagnosis of T. gondii relies on seroconversion, which can be delayed or absent in immunocompromised transplant patients. For these patients, PCR is considered instrumental in forming a diagnosis[60].

Some cases of ocular infections by Scedosporium, which is usually found in soil or sewage-polluted water, have been reported in post-transplant and immunosuppressed patients. The treatment involves systemic antifungal therapy, intravitreous injections of amphotericin B or voriconazole, and vitrectomy[33]. A few cases of conjunctivitis and keratitis by Microsporidia, which are intracellular, spore-like fungi, have also been reported[27].

Neurotoxic complications: Studies have reported that nearly one-third of transplant patients have neurotoxic complications, with the incidence reported between 10% to 59%, the majority of which are reported in liver transplant patients[61-63]. These can range from mild complications such as tremors and paresthesia to severe complications such as optic neuropathy and leukoencephalopathy. Out of all immunosuppressive drugs used post-transplant, calcineurin inhibitors (CIs) such as tacrolimus are the main drugs associated with neurotoxicity[61].

Optic neuropathy is one of the rare complications of tacrolimus, which may occur at any time post-initiation. The symptoms, usually bilateral, may range from a decrease in visual acuity to blindness[64,65]. In a study by Yun et al[66], the fundoscopic findings of some patients revealed no blood supply to the optic disc post symptom onset after Tacro

Another study by Yamauchi et al[67] concluded that different CNS pharmacokinetics in different individuals can be responsible for making them more sensitive to Tacrolimus, hence, Tacrolimus-induced optic neuropathy. Some studies have also reported cases of Cyclosporine-induced optic neuropathy even at the therapeutic levels[68]. Despite the early identification, optic neuropathy is often irreversible. In a case report by Alnahdi et al[64], the symptoms started unilaterally 16 years after Tacrolimus initiation and despite the discontinuation, the symptoms persisted. Hence, all transplant patients should be educated about the possibility of these symptoms and the importance of seeking urgent medical care to avoid progression[64].

Brain and orbital MRI can be used to identify optic nerve inflammation, indicated by the presence of contrast enhan

Retinal vascular complications: Retinal vascular issues such as central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) have been observed following liver transplantation. In a study involving 3656 organ transplant recipients, ophthalmic evaluation of 1198 patients revealed CRVO development exclusively in liver transplant patients. Relative to other transplant patients, liver transplant patients were receiving higher doses and a longer duration of immunosuppressive therapy including tacrolimus, prednisone and mycophenolate. Notably, none of these patients had preexisting hypertension or a history of other hematologic disorders. It was presumed that hypertension and hyperlipidemia, secondary to the large doses and extended duration of immunosuppressive therapy in LT patients, contributed to the development of CRVO[71]. In another study of 1205 patients following organ transplant, CRVO was diagnosed in five patients, all of whom had undergone lung transplantation. Hematological evaluation in these cases demonstrated alterations in blood coagulability secondary to hepatic failure, normalization of absolute platelet count, international normalized ratio and activated partial thromboplastin time. Additionally, an increase in factor VIII and activated protein C was observed[72].

Tacrolimus therapy has been independently linked to CRVO due to direct neurotoxicity. This may result in axonal swelling, increased water content, and edema of neural tissues[73,74]. As the central retinal vein is involved, it leads to ischemic CRVO and cystic macular edema. These complications have shown improvement with treatment using antiangiogenics such as aflibercept or ranibizumab, as well as intravitreal dexamethasone implants[74].

Dry eye disease: It is a multifactorial disease that can cause ocular discomfort, visual disruption, tear film instability and surface damage[75]. Studies have reported an incidence of 22.5% in liver transplant patients[76]. Regardless of initiating etiology, inflammation is usually the factor in the maintenance of disease. Inflammatory mediators promote apoptosis in the lacrimal gland and of ocular surface epithelial cells, interfering with normal differentiation and causing lacrimal dysfunction[77]. Ophthalmic examination including Schirmer test, tear film break-up time and ocular surface changes can be used to establish a diagnosis[78]. Management includes standard dry eye disease therapies.

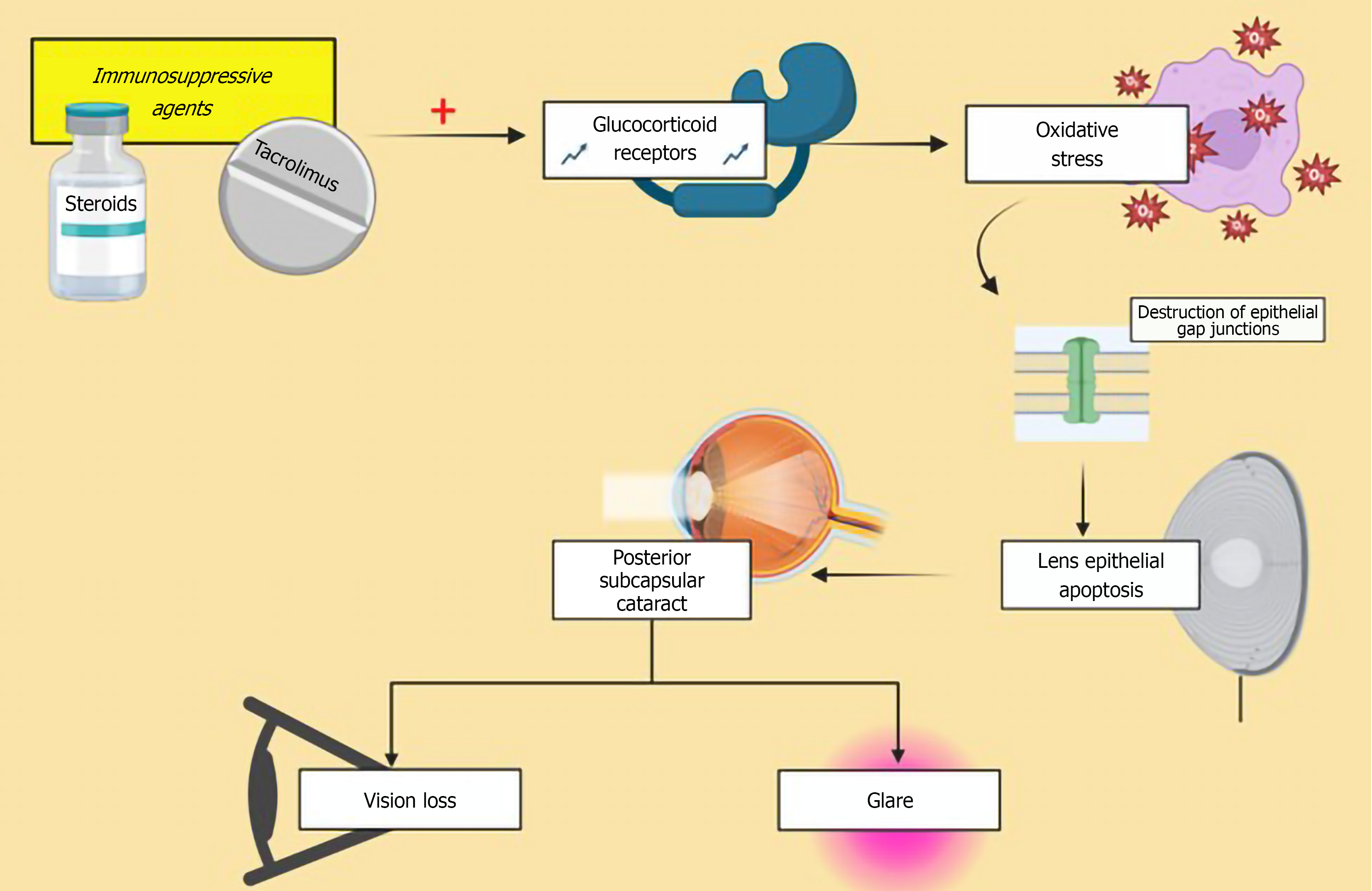

Lens related pathologies: Cataract formation is a well-documented complication among organ transplant recipients, frequently associated with the use of postoperative medications including steroids, cyclosporine, and tacrolimus[79]. Posterior subcapsular cataracts (PSC), are most commonly reported in liver transplant recipients, with studies reporting incidence up to 45%[76]. As the name suggests, in PSCs the cataract develops in the posterior cortical region of the lens, just anterior to the posterior capsule. The pathogenesis involves multiple factors including oxidative damage, role of glucocorticoid receptors and defective differentiation due to dysregulated apoptotic pathways[80] (Figure 2). The duration of the sustained steroid treatment has been associated with development of cataract[81]. Reduction in drug dosage or discontinuation of corticosteroids can be particularly beneficial for older patients to prevent development of cataract[82]. Patients present with glare and progressive diminution of visual acuity. Diagnosis is made through slit-lamp examination. Management follows the standard approach for visually significant cataracts, involving surgical removal and replacement of the natural lens.

Central serous chorioretinopathy: Central serous chorioretinopathy (CSC) post-transplant, similar to idiopathic CSC, is characterized by the appearance of focal or multifocal detachments of the neurosensory retina, retinal pigment epithelium or both, usually with an identifiable inkblot or smokestack pattern of leakage on fluorescein angiography. The patho

Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) are a spectrum of diseases caused by lymphoplasmacytic proliferations that arise in the setting of post-transplant immunosuppression, causing uncontrolled proliferation of B cells[85]. Immunosuppressive therapy inhibits T cell function, which leads to a reduction in B cell growth suppression[86]. PTLDs range from benign polymorphic, polyclonal proliferations to aggressive monomorphic, monoclonal lym

The incidence of PTLD is reported to be significantly higher in children 9.7% than in adults 2.9%, with an overall incidence of 4.3%[88]. Ocular incidence in PTLD is very rare, with only 24 cases reported in literature to date.

Primary ocular PTLDs are a distinct, late-onset, polyclonal lymphoproliferation primarily seen in pediatric liver transplant patients[89]. Histopathologically, it is characterized by a mixture of lymphocytes and plasma cells diffusely infiltrating the uveal tissue. Cho et al[91] reported that anterior uveitis and iris nodules are the most common ocular manifestations of PTLDs, however posterior segment can also be involved, presenting as vitritis, subretinal mass and optic disc swelling[90,91]. Notably, some patients may remain asymptomatic.

The majority of PTLD cases are associated with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection[92]. EBV induces uncontrolled proliferation of B cells, which are normally regulated by cytotoxic T-cells and natural killer cells[92,93]. Treatment of ocular PTLD involves systemic therapy with rituximab, often in combination with antiviral agents and a reduction in immunosuppressive therapy, especially in cases with concomitant central nervous system involvement[90]. Table 2 provides a summary of the non-infectious complications post-liver transplant.

| Disease | Pathogenesis | Clinical manifestation | Treatment |

| Dry eye disease | Apoptosis of the lacrimal gland due to inflammation | Gritty sensation, visual disruption | Artificial tears |

| Cataract | Oxidative stress | Glare, diminution of visual acuity | Surgery |

| Central retinal vein occlusion | Hyperlipidemia, Neurotoxicity | Sudden vision loss | Anti-VEGF, intravitreous dexamethasone implants |

| Ocular PTLD | B cell overgrowth due to T-cell suppression | Uveitis and subretinal mass | Rituximab, antiviral agents |

The review highlights the broad spectrum of ocular complications that can arise post-liver transplantation. The immunosuppressive regimens essential for graft survival predispose recipients to a range of ocular manifestations, which can significantly impact visual prognosis and overall morbidity. The increased susceptibility to opportunistic infections, such as CMV retinitis, underscores the necessity of robust prophylactic strategies and prompt, aggressive treatment. Simultaneously, non-infectious complications are prevalent and significantly impact vision. The successful management of these diverse ocular conditions requires a high index of suspicion and a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach. Pre-transplant ophthalmologic screening is essential to identify and manage pre-existing conditions, while vigilant post-transplant surveillance is crucial for the early detection and treatment of emerging complications. Future research should continue to refine prophylactic regimens and therapeutic strategies tailored to this vulnerable population.

| 1. | Kwong AJ, Kim WR, Lake JR, Schladt DP, Handarova D, Howell J, Schumacher B, Weiss S, Snyder JJ, Israni AK. OPTN/SRTR 2023 Annual Data Report: Liver. Am J Transplant. 2025;25:S193-S287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Coskuncan NM, Jabs DA, Dunn JP, Haller JA, Green WR, Vogelsang GB, Santos GW. The eye in bone marrow transplantation. VI. Retinal complications. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:372-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Porter R, Crombie AL, Gardner PS, Uldall RP. Incidence of ocular complications in patients undergoing renal transplantation. Br Med J. 1972;3:133-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Quinlan MF, Salmon JF. Ophthalmic complications after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:252-255. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Papanicolaou GA, Meyers BR, Fuchs WS, Guillory SL, Mendelson MH, Sheiner P, Emre S, Miller C. Infectious ocular complications in orthotopic liver transplant patients. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1172-1177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lizaola-Mayo BC, Rodriguez EA. Cytomegalovirus infection after liver transplantation. World J Transplant. 2020;10:183-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Razonable RR, Humar A. Cytomegalovirus in solid organ transplant recipients-Guidelines of the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 76.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Ljungman P, Griffiths P, Paya C. Definitions of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in transplant recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1094-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 947] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bessat JD, Lavanchy DL, Bickel M. [Change in gingival fluid pH during periodontal treatment: longitudinal study]. J Parodontol. 1988;7:57-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Silva F, Ficher KN, Viana L, Coelho I, Rezende JT, Wagner D, Vaz ML, Foresto R, Silva Junior HT, Pestana JM. Presumed cytomegalovirus retinitis late after kidney transplant. J Bras Nefrol. 2022;44:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Erakgun T, Afrashi F, Nalbantgil S, Ozbaran M, Mentes J. Asymptomatic cytomegalovirus retinitis after cardiac transplantation. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fishburne BC, Mitrani AA, Davis JL. Cytomegalovirus retinitis after cardiac transplantation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1998;125:104-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pollard RB, Egbert PR, Gallagher JG, Merigan TC. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in immunosuppressed hosts. I. Natural history and effects of treatment with adenine arabinoside. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:655-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scherger SJ, Molina KC, Palestine AG, Pecen PE, Bajrovic V. Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in the Modern Era of Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2024;56:1696-1701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Squires JE, Sisk RA, Balistreri WF, Kohli R. Isolated unilateral cytomegalovirus retinitis: a rare long-term complication after pediatric liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2013;17:E16-E19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Engelmann C, Sterneck M, Weiss KH, Templin S, Zopf S, Denk G, Eurich D, Pratschke J, Weiss J, Braun F, Welker MW, Zimmermann T, Knipper P, Nierhoff D, Lorf T, Jäckel E, Hau HM, Tsui TY, Perrakis A, Schlitt HJ, Herzer K, Tacke F. Prevention and Management of CMV Infections after Liver Transplantation: Current Practice in German Transplant Centers. J Clin Med. 2020;9:2352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Humar A, Lebranchu Y, Vincenti F, Blumberg EA, Punch JD, Limaye AP, Abramowicz D, Jardine AG, Voulgari AT, Ives J, Hauser IA, Peeters P. The efficacy and safety of 200 days valganciclovir cytomegalovirus prophylaxis in high-risk kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1228-1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kotton CN, Kumar D, Manuel O, Chou S, Hayden RT, Danziger-Isakov L, Asberg A, Tedesco-Silva H, Humar A; Transplantation Society International CMV Consensus Group. The Fourth International Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Cytomegalovirus in Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation. 2025;109:1066-1110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 64.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rifkin LM, Minkus CL, Pursell K, Jumroendararasame C, Goldstein DA. Utility of Leflunomide in the Treatment of Drug Resistant Cytomegalovirus Retinitis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2017;25:93-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pearce WA, Yeh S, Fine HF. Management of Cytomegalovirus Retinitis in HIV and Non-HIV Patients. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2016;47:103-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dhal U, Raju S, Singh AD, Mehta AC. "For your eyes only": ophthalmic complications following lung transplantation. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:6285-6297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Singh N, Dummer JS, Kusne S, Breinig MK, Armstrong JA, Makowka L, Starzl TE, Ho M. Infections with cytomegalovirus and other herpesviruses in 121 liver transplant recipients: transmission by donated organ and the effect of OKT3 antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Basse G, Mengelle C, Kamar N, Ribes D, Selves J, Cointault O, Suc B, Rostaing L. Disseminated herpes simplex type-2 (HSV-2) infection after solid-organ transplantation. Infection. 2008;36:62-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Oshry T, Lifshitz T. Intravenous acyclovir treatment for extensive herpetic keratitis in a liver transplant patient. Int Ophthalmol. 1997-1998;21:265-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Choong K, Walker NJ, Apel AJ, Whitby M. Aciclovir-resistant herpes keratitis. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;38:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wilck MB, Zuckerman RA; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Herpes simplex virus in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 4:121-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Leal SM Jr, Rodino KG, Fowler WC, Gilligan PH. Practical Guidance for Clinical Microbiology Laboratories: Diagnosis of Ocular Infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2021;34:e0007019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Vrcek I, Choudhury E, Durairaj V. Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus: A Review for the Internist. Am J Med. 2017;130:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Burroughs M, Moscona A. Immunization of pediatric solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:857-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Binder MI, Chua J, Kaiser PK, Procop GW, Isada CM. Endogenous endophthalmitis: an 18-year review of culture-positive cases at a tertiary care center. Medicine (Baltimore). 2003;82:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Pergam SA, Limaye AP; AST Infectious Diseases Community of Practice. Varicella zoster virus in solid organ transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13 Suppl 4:138-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hernandez Mdel P, Martin P, Simkins J. Infectious Complications After Liver Transplantation. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2015;11:741-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Durand ML. Bacterial and Fungal Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2017;30:597-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 291] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 34. | Azmi AZ, Patrick S, Isa MIB, Ab Ghani S. Mixed Clinical Pictures of Endogenous Endophthalmitis in a Relapse Leukemic Patient. Cureus. 2023;15:e49167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Breitkopf R, Treml B, Simmet K, Bukumirić Z, Fodor M, Senoner T, Rajsic S. Incidence of Invasive Fungal Infections in Liver Transplant Recipients under Targeted Echinocandin Prophylaxis. J Clin Med. 2023;12:1520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Scolarici M, Jorgenson M, Saddler C, Smith J. Fungal Infections in Liver Transplant Recipients. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7:524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lahmer T, Messer M, Schwerdtfeger C, Rasch S, Lee M, Saugel B, Schmid RM, Huber W. Invasive mycosis in medical intensive care unit patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis. Mycopathologia. 2014;177:193-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Romero FA, Razonable RR. Infections in liver transplant recipients. World J Hepatol. 2011;3:83-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 39. | Barchiesi F, Mazzocato S, Mazzanti S, Gesuita R, Skrami E, Fiorentini A, Singh N. Invasive aspergillosis in liver transplant recipients: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcomes in 116 cases. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:204-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Varma D, Thaker HR, Moss PJ, Wedgwood K, Innes JR. Use of voriconazole in candida retinitis. Eye (Lond). 2005;19:485-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Klotz SA, Penn CC, Negvesky GJ, Butrus SI. Fungal and parasitic infections of the eye. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2000;13:662-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Gentile P, Ragusa E, Bruno R, Ceccarelli F, Adani C, Bolletta E, De Simone L, Gozzi F, Cimino L. Endogenous Candida Endophthalmitis: An Update on Epidemiological, Pathogenetic, Clinical, and Therapeutic Aspects. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2025;33:1777-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE Jr, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:503-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2308] [Cited by in RCA: 2062] [Article Influence: 121.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Akler ME, Vellend H, McNeely DM, Walmsley SL, Gold WL. Use of fluconazole in the treatment of candidal endophthalmitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:657-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Patel TP, Zacks DN, Dedania VS. Antimicrobial guide to posterior segment infections. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2021;259:2473-2501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Durand ML. Endophthalmitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 27.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 47. | Haseeb AA, Elhusseiny AM, Siddiqui MZ, Ahmad KT, Sallam AB. Fungal Endophthalmitis: A Comprehensive Review. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;7:996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Hunt KE, Glasgow BJ. Aspergillus endophthalmitis. An unrecognized endemic disease in orthotopic liver transplantation. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:757-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Spadea L, Giannico MI. Diagnostic and Management Strategies of Aspergillus Endophthalmitis: Current Insights. Clin Ophthalmol. 2019;13:2573-2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Das T, Joseph J, Jakati S, Sharma S, Velpandian T, Padhy SK, Das VA, Shivaji S, Nayak S, Behera UC, Mishra DK, Gandhi J, Dave VP, Pathengay A. Understanding the science of fungal endophthalmitis - AIOS 2021 Sengamedu Srinivas Badrinath Endowment Lecture. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70:768-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hadaschik E, Koschny R, Willinger B, Hallscheidt P, Enk A, Hartschuh W. Pulmonary, rhino-orbital and cutaneous mucormycosis caused by Rhizomucor pusillus in an immunocompromised patient. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;37:355-357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Ferry AP, Abedi S. Diagnosis and management of rhino-orbitocerebral mucormycosis (phycomycosis). A report of 16 personally observed cases. Ophthalmology. 1983;90:1096-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Downie JA, Francis IC, Arnold JJ, Bott LM, Kos S. Sudden blindness and total ophthalmoplegia in mucormycosis. A clinicopathological correlation. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1993;13:27-34. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Lee BL, Holland GN, Glasgow BJ. Chiasmal infarction and sudden blindness caused by mucormycosis in AIDS and diabetes mellitus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;122:895-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sabhapandit S, Sharma M, Sekaran A, Menon B, Kulkarni A, Tr S, Nagaraja Rao P, Nageshwar Reddy D. Postliver Transplantation Rhino-Orbital Mucormycosis, an Unexpected Cause of a Downhill Course. Case Reports Hepatol. 2022;2022:5413315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Sun HY, Forrest G, Gupta KL, Aguado JM, Lortholary O, Julia MB, Safdar N, Patel R, Kusne S, Singh N. Rhino-orbital-cerebral zygomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2010;90:85-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Almyroudis NG, Sutton DA, Linden P, Rinaldi MG, Fung J, Kusne S. Zygomycosis in solid organ transplant recipients in a tertiary transplant center and review of the literature. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2365-2374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Osseis M, Lim C, Salloum C, Azoulay D. Mucormycosis in liver transplantation recipients a systematic review. Surg Open Dig Adv. 2023;10:100088. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 59. | Blanc-Jouvan M, Boibieux A, Fleury J, Fourcade N, Gandilhon F, Dupouy-Camet J, Peyron F, Ducerf C. Chorioretinitis following liver transplantation: detection of Toxoplasma gondii in aqueous humor. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:184-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Gourishankar S, Doucette K, Fenton J, Purych D, Kowalewska-Grochowska K, Preiksaitis J. The use of donor and recipient screening for toxoplasma in the era of universal trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis. Transplantation. 2008;85:980-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Senzolo M, Ferronato C, Burra P. Neurologic complications after solid organ transplantation. Transpl Int. 2009;22:269-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 62. | Sakhuja V, Sud K, Kalra OP, D'Cruz S, Kohli HS, Jha V, Gupta K, Vasishta RK. Central nervous system complications in renal transplant recipients in a tropical environment. J Neurol Sci. 2001;183:89-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Uckan D, Cetin M, Yigitkanli I, Tezcan I, Tuncer M, Karasimav D, Oguz KK, Topçu M. Life-threatening neurological complications after bone marrow transplantation in children. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Alnahdi MA, Al Malik YM. Delayed tacrolimus-induced optic neuropathy. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2019;24:324-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Rasool N, Boudreault K, Lessell S, Prasad S, Cestari DM. Tacrolimus Optic Neuropathy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2018;38:160-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Yun J, Park KA, Oh SY. Bilateral ischemic optic neuropathy in a patient using tacrolimus (FK506) after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2010;89:1541-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Yamauchi A, Ieiri I, Kataoka Y, Tanabe M, Nishizaki T, Oishi R, Higuchi S, Otsubo K, Sugimachi K. Neurotoxicity induced by tacrolimus after liver transplantation: relation to genetic polymorphisms of the ABCB1 (MDR1) gene. Transplantation. 2002;74:571-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Akagi T, Manabe S, Ishigooka H. A case of cyclosporine-induced optic neuropathy with a normal therapeutic level of cyclosporine. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2010;54:102-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Sierra-Hidalgo F, Martínez-Salio A, Moreno-García S, de Pablo-Fernández E, Correas-Callero E, Ruiz-Morales J. Akinetic mutism induced by tacrolimus. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2009;32:293-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Zhang W, Egashira N, Masuda S. Recent Topics on The Mechanisms of Immunosuppressive Therapy-Related Neurotoxicities. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:3210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Chung H, Kim KH, Kim JG, Lee SY, Yoon YH. Retinal complications in patients with solid organ or bone marrow transplantations. Transplantation. 2007;83:694-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Chung H, Yoon SY, Kim JG, Yoon YH. Central retinal vein occlusion after liver transplantation. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87:572-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Donnadieu B, Amouyal F, Hoffart L, Matonti F. Central retinal vein occlusion-associated tacrolimus after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;98:e94-e95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Cerveró A, González Bores P, Casado A, Ruiz Sancho MD, Hernández Hernández JL, Napal Lecumberri JJ. Retinal vein occlusion in solid organ transplant recipients. Study of 4 cases and literature review. Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol (Engl Ed). 2020;95:615-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | The definition and classification of dry eye disease: report of the Definition and Classification Subcommittee of the International Dry Eye WorkShop (2007). Ocul Surf. 2007;5:75-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1844] [Cited by in RCA: 2222] [Article Influence: 116.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Sarigul Sezenoz A, Gokgoz G, Kirci Dogan I, Gur Gungor S, Oto S, Haberal M. Ocular Symptoms in Kidney, Liver, and Heart Transplant Patients. Exp Clin Transplant. 2024;22:141-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Donnenfeld E, Pflugfelder SC. Topical ophthalmic cyclosporine: pharmacology and clinical uses. Surv Ophthalmol. 2009;54:321-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Trung NL, Toan PQ, Trung NK, Tuan VA, Huyen NT. Eye Lesions in Patients After One Year of Kidney Transplantation. Clin Ophthalmol. 2023;17:2861-2869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Lanzetta P, Monaco P. Major ocular complications after organ transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:3046-3048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Petersen A, Carlsson T, Karlsson JO, Jonhede S, Zetterberg M. Effects of dexamethasone on human lens epithelial cells in culture. Mol Vis. 2008;14:1344-1352. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Berindán K, Nemes B, Szabó RP, Módis L Jr. Ophthalmic Findings in Patients After Renal Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2017;49:1526-1529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Keswani RN, Ahmed A, Keeffe EB. Older age and liver transplantation: a review. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:957-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Fawzi AA, Holland GN, Kreiger AE, Heckenlively JR, Arroyo JG, Cunningham ET Jr. Central serous chorioretinopathy after solid organ transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:805-13.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Abalem MF, Carricondo PC, Pimentel SL, Takahashi WY. Idiopathic organ transplant chorioretinopathy after liver transplantation. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med. 2015;2015:964603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Abbas F, El Kossi M, Shaheen IS, Sharma A, Halawa A. Post-transplantation lymphoproliferative disorders: Current concepts and future therapeutic approaches. World J Transplant. 2020;10:29-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 86. | Baer I, Zimmermann HB. [Gaucher's disease in the adult]. Dtsch Gesundheitsw. 1967;22:1297-1300. [PubMed] |

| 87. | Swerdlow SH. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders: a morphologic, phenotypic and genotypic spectrum of disease. Histopathology. 1992;20:373-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Jain A, Nalesnik M, Reyes J, Pokharna R, Mazariegos G, Green M, Eghtesad B, Marsh W, Cacciarelli T, Fontes P, Abu-Elmagd K, Sindhi R, Demetris J, Fung J. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in liver transplantation: a 20-year experience. Ann Surg. 2002;236:429-36; discussion 436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | O'hara M, Lloyd WC 3rd, Scribbick FW, Gulley ML. Latent intracellular Epstein-Barr Virus DNA demonstrated in ocular posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder mimicking granulomatous uveitis with iris nodules in a child. J AAPOS. 2001;5:62-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Iu LP, Yeung JC, Loong F, Chiang AK. Successful treatment of intraocular post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder with intravenous rituximab. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:169-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Cho AS, Holland GN, Glasgow BJ, Isenberg SJ, George BL, McDiarmid SV. Ocular involvement in patients with posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:183-189. [PubMed] |

| 92. | Ho M, Miller G, Atchison RW, Breinig MK, Dummer JS, Andiman W, Starzl TE, Eastman R, Griffith BP, Hardesty RL. Epstein-Barr virus infections and DNA hybridization studies in posttransplantation lymphoma and lymphoproliferative lesions: the role of primary infection. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:876-886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Wu L, Rappaport DC, Hanbidge A, Merchant N, Shepherd FA, Greig PD. Lymphoproliferative disorders after liver transplantation: imaging features. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:200-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/