Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111959

Revised: October 9, 2025

Accepted: December 9, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 184 Days and 7.4 Hours

The use of induction immunosuppression agents has improved kidney transplant outcomes, but selecting the optimal agent remains a point of debate.

To compare the long-term outcomes of kidney transplant recipients receiving al

Kidney transplant recipients who received alemtuzumab or basiliximab induction from 2014 to 2019 across two nephrology centres in Northwest England were evaluated. Propensity score matching at a 1:1.5 ratio ensured comparability between cohorts. Baseline characteristics, immunosuppression regimens, and outcomes were analyzed. Linear, binary logistics and Cox proportional hazard regression models.

A total of 436 recipients were included, with a median follow-up of 5.2 years. The matched cohort (n = 262) had a mean age of 51.1 ± 13.5 years; 39% were female and 92% were white. There was no significant difference in the cumulative incidence of acute rejection [odds ratio (OR) = 2.10; 95%CI: 0.9-4.9; P = 0.110]. Compared with basiliximab, alemtuzumab was associated with lower estimated glomerular filtration rate at 12 months (-6.6 mL/minute/1.73 m2; 95%CI: -10.5 to -2.7; P < 0.001) and higher risks of cytomegalovirus viremia (OR = 3.2; 95%CI: 1.6-6.5; P < 0.001), BK viremia (OR = 2.4; 95%CI: 1.1-5.5; P = 0.02), post-transplant malignancy (OR = 6.2; 95%CI: 1.6-29.9; P = 0.013), and death-censored graft loss (hazard ratio = 3.6; 95%CI: 1.2-11.4; P = 0.03). No significant differences were observed in post-transplant glomerulonephritis or recipient mortality.

In this propensity score-matched analysis, alemtuzumab induction was associated with lower graft function at 12 months and higher risks of viral infection, post-transplant malignancy, and graft loss compared with basiliximab. These findings highlight the need for further studies to confirm the long-term safety and effectiveness of alemtuzumab in kidney transplantation.

Core Tip: This retrospective cohort study compared real-world outcomes of alemtuzumab and basiliximab induction in kidney transplant recipients from two tertiary centers in North-West England, one routinely using alemtuzumab and the other exclusively basiliximab. Using propensity score matching to reduce confounding, we evaluated graft function, graft and patient survival, acute rejection, infection, and other long-term complications. Alemtuzumab induction was found to be associated with lower estimated glomerular filtration rate, and higher risks of cytomegalovirus and BK viremia, post-transplant malignancy, and death-censored graft loss compared with basiliximab. These findings emphasize the need for individualized selection of induction therapy, balancing the potent immunosuppressive effects of alemtuzumab against its potential for adverse outcomes, and support tailored approaches based on recipient risk profile and center-specific experience.

- Citation: Chukwu CA, Kalra PA, Lowe M, Poulton K, Augustine T, Rao A. Outcomes of basiliximab vs alemtuzumab induction in kidney allograft recipients with matched immunological Profiles: A retrospective cohort study. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 111959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/111959.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111959

The use of monoclonal and polyclonal antibody-based induction immunosuppression in kidney transplantation has significantly improved both short-term and long-term outcomes. It has enabled the utilisation of less-than-optimal donor kidneys, including expanded criteria donors and has improved the outcomes of high immunologic risk recipients such as highly sensitised recipients, Black Caribbean recipients, and repeat transplant recipients[1,2]. Two categories of induction agents are currently used for kidney transplantation: (1) Lymphocyte-depleting; and (2) Non-lymphocyte-depleting agents.

Alemtuzumab (Campath) is a recombinant anti-CD52 pan-lymphocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody that is widely used in the United Kingdom.

Basiliximab (Simulect), an interleukin-2 receptor antagonist (IL-2RA), is the main non-lymphocyte-depleting induction agent employed in the United Kingdom.

Despite their extensive use, the optimal induction agent and regimen remain subjects of ongoing debate amongst researchers and transplant clinicians. This controversy arises because the comparative effectiveness of commonly used agents such as alemtuzumab and basiliximab has yielded mixed results across studies. The inconsistency is partly due to heterogeneity in study populations, dosing strategies, and maintenance immunosuppressive regimens and partly because selection of induction therapy requires balancing the competing risks of acute rejection, infection, malignancy, and long-term graft survival[1,3]. Consequently, these agents are usually administered to patients with widely differing baseline clinical, demographic, and immunologic characteristics. Alemtuzumab recipients, for example, tend to be younger and have a higher immunologic risk profile compared with basiliximab recipients. This makes direct comparison between groups with fundamentally dissimilar baseline characteristics inherently challenging[1].

Furthermore, there is a paucity of head-to-head comparison studies[4-6] evaluating alemtuzumab and (IL-2RA) induction in relation to rejection rates, graft and patient survival, and complications such as DNA virus infection and malignancy[7-9].

This study therefore aimed to compare the outcomes of kidney transplant recipients (KTR) who received alemtuzumab vs basiliximab induction, using propensity score matching (PSM) to ensure comparable baseline immunologic risk profiles.

This retrospective comparative cohort study evaluated adult KTR who received kidney transplants between January 2014 and December 2019 at two tertiary nephrology centres in northwest England (Hospital A and Hospital B). Subjects received induction immunosuppression with either alemtuzumab (Campath) or basiliximab (Simulect) at the time of transplant. Hospital A predominantly used alemtuzumab for immunosuppression induction whereas Hospital B used basiliximab as an induction agent in most kidney transplantations reserving alemtuzumab for simultaneous kidney and pancreas transplantation.

Subjects were drawn from the transplant recipient databases of two participating hospitals, designated as Hospital A and Hospital B. Hospital A employed a combination of alemtuzumab and basiliximab for induction, while Hospital B predominantly utilised basiliximab. At Hospital A, the indications for alemtuzumab induction included transplantation of a donation-after-circulatory-death allograft, donation-after-brain-death allografts with a cold ischaemic time exceeding 24 hours, allografts with a 2-DR mismatch, panel reactive antibody (PRA) greater than 20%, positive human leucocyte antigen (HLA) crossmatch, and previous early graft loss due to acute rejection. The dosing regimen for alemtuzumab involved a 30 mg subcutaneous administration at transplantation, with a second dose given a day later for recipients under 60 years old; those over 60 years received a single 30 mg dose. Recipients not meeting these indications received basiliximab induction, dosed at 20 mg on days 0 and 4. Conversely, Hospital B employed basiliximab 20 mg intravenously on days 0 and 4 post-transplant, with rare instances of alemtuzumab induction in multi-organ transplant recipients.

Due to evolving immunosuppression regimens and data inconsistency before 2014, the study focused on KTR from 2014 onwards. In addition, recipients transplanted after 2019 were excluded due to the influence of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on immunosuppression practices.

The study exclusively considered kidney-only transplant recipients who received induction immunosuppression with either alemtuzumab (from Hospital A) or basiliximab (from Hospital B), ensuring no prior exposure to alemtuzumab. Exclusion criteria included recipients with prior alemtuzumab exposure for indications other than transplant immunosuppression induction, previous exposure to other lymphocyte-depleting agents (e.g., rituximab, thymoglobulin), multiorgan transplant recipients, and those experiencing graft loss within three months post-transplantation. Patients who experienced early graft loss (within 3 months) were excluded because their subsequent follow-up data (for outcomes such as acute rejection, viral infections, malignancy, and long-term graft function) would not be available or meaningful in the context of our study endpoints. This ensured that the study focused on medium-term and long-term outcomes among recipients with sustained allograft function beyond the immediate post-transplant period.

In Hospital A, recipients who underwent alemtuzumab induction were managed with a steroid-free, calcineurin inhibitor (CNI)-based regimen, typically involving tacrolimus (or cyclosporin if tacrolimus was contraindicated). The target tacrolimus trough level was 5-8 ng/L. Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) was also administered at a daily dose of 1000 mg in two divided doses. Recipients classified as high immunological risk, with factors such as a 2-DR mismatch, PRA > 20%, or a history of graft loss from acute rejection, had a higher target tacrolimus trough level of 8-12 ng/L for the initial 6 months, followed by 5-8 ng/L thereafter, in conjunction with MMF. Additionally, recipients aged over 60 years, who received a single dose of alemtuzumab, received tacrolimus targeting a trough level of 8-12 ng/L for the first 6 months, followed by 5-8 ng/L, and MMF at a dose of 1000 mg daily in two divided doses. Glucocorticoids were given for the initial 3 months post-transplantation.

In Hospital B, recipients who underwent induction with the IL-2RA basiliximab were treated with CNI-based maintenance immunosuppression, using either tacrolimus or cyclosporin. Those without contraindications also receive an anti-proliferative immunosuppressant, either mycophenolic acid or azathioprine. Steroid treatment for recipients with standard immunologic risk was typically restricted to less than two weeks. However, individuals at high immunologic risk, such as younger recipients and older donor age, calculated PRA greater than 20%, presence of a donor-specific antibody, blood group incompatibility, delayed onset of graft function, or cold ischemia time (CIT) exceeding 24 hours, received a more prolonged course of corticosteroid maintenance. The necessity for continued steroid administration was re-evaluated after 3 months and 6 months, with the potential for discontinuation if the patient was deemed to be at low risk of acute rejection or high risk of infections.

Although Hospital A had a steroid avoidance regimen, a significant number of patients were started on steroids as a replacement for MMF due to severe lymphopenia linked to the combination of alemtuzumab induction and MMF maintenance or post-transplant DNA viremia.

The data for this study were extracted from the hospital's electronic patient records, comprising relevant information obtained from clinical letters, notes, and laboratory results.

Data collection continued until clinical endpoints of graft loss, patient death, loss to follow-up, or study conclusion on December 31, 2021. Subjects were censored at the occurrence of any of the above endpoints, whichever came first.

Baseline demographic variables, comorbidities, transplant factors, maintenance immunosuppression, and post-transplant complications were recorded.

The exposure variable was induction type, specifically alemtuzumab induction vs basiliximab induction.

Potential confounders and effect modifiers included recipient age, ethnicity, the primary cause of end-stage kidney disease, donor type, donor and recipient cytomegalovirus (CMV) serostatus, degree of HLA mismatch, crossmatch status, transplant year, CIT, steroid regimen, baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), PRA, recipients were also categorised into age groups < 60 years and ≥ 60 years (with recipients aged 60 years and above receiving half the dose of alemtuzumab compared to those less than 60 years) and CIT categories (≤ 24 hours and > 24 hours).

Outcome variables included change in eGFR at 1 year, history of acute rejection, history of post-transplant DNA virus infections CMV, Epstein-Barr virus and BK viremia respectively, history of post-transplant malignancy, history of post-transplant glomerulonephritis (GN), death censored graft survival and recipient survival (RS).

Graft loss was defined as a return to dialysis or re-transplantation. Post-transplant malignancy included all de-novo cancers after transplantation, excluding non-melanoma skin cancers. Baseline eGFR was defined as eGFR at 3 months post-transplantation and was calculated using the modification of diet in the renal disease equation. Acute rejection was confirmed through allograft biopsy.

PSM: We conducted a PSM analysis to compare the outcomes between alemtuzumab and basiliximab recipients. We aimed to achieve a matched ratio of 1:2. The propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression, incorporating covariates such as recipient’s age, donor type, CIT, CIT ≤ or > 24 hours, year of transplantation, age < or ≥ 60 years, HLA-DR mismatch and the PRA. These covariates were selected based on the indications for alemtuzumab induction in Hospital A. MatchIt software in R was used for PSM[10]. Nearest neighbour greedy matching was performed using a calliper width of 0.25 standard deviations of the logit of the propensity score. The matched sample consisted of 101 alemtuzumab recipients and 160 basiliximab recipients resulting in a matching ratio of approximately 1:1.5. Despite not achieving a perfect 1:2 ratio, the matched groups were well-balanced in terms of observed covariates, indicating successful PSM. Covariate balance was assessed using standardised mean differences (SMDs), with an absolute SMD of ≤ 0.10 considered to indicate balance. Following PSM, two variables with significant residual imbalance (pre-emptive transplantation and primary renal disease) were additionally adjusted for in all multivariable regression models used to estimate treatment effects.

Covariate balance after PSM: Overall, the propensity matching improved the balance of baseline characteristics between the Simulect group and Campath group, evidenced by a well-balanced SMDs on all the variables on which the cohorts were matched as shown in the Supplementary Figure 1. Before matching, there were notable differences in baseline characteristics between the alemtuzumab and basiliximab groups, with some variables having SMDs greater than 0.1. However, after PSM, all variables achieved balance, with SMD approximately 0.1 for all matched variables.

Inferential analysis was conducted on the matched cohort. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were expressed as means with standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges depending on the distribution. Propensity scores were used as covariates in linear regression for eGFR change at 12 months, logistic regression for binary outcomes (acute rejection, post-transplant GN, post-transplant viral infections), and Cox proportional hazard regression for death-censored graft survival (DCGS) and RS. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05, and R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, version 4.2.2) was used for analysis. Further analyses of the treatment effects were subsequently performed on the matched cohort.

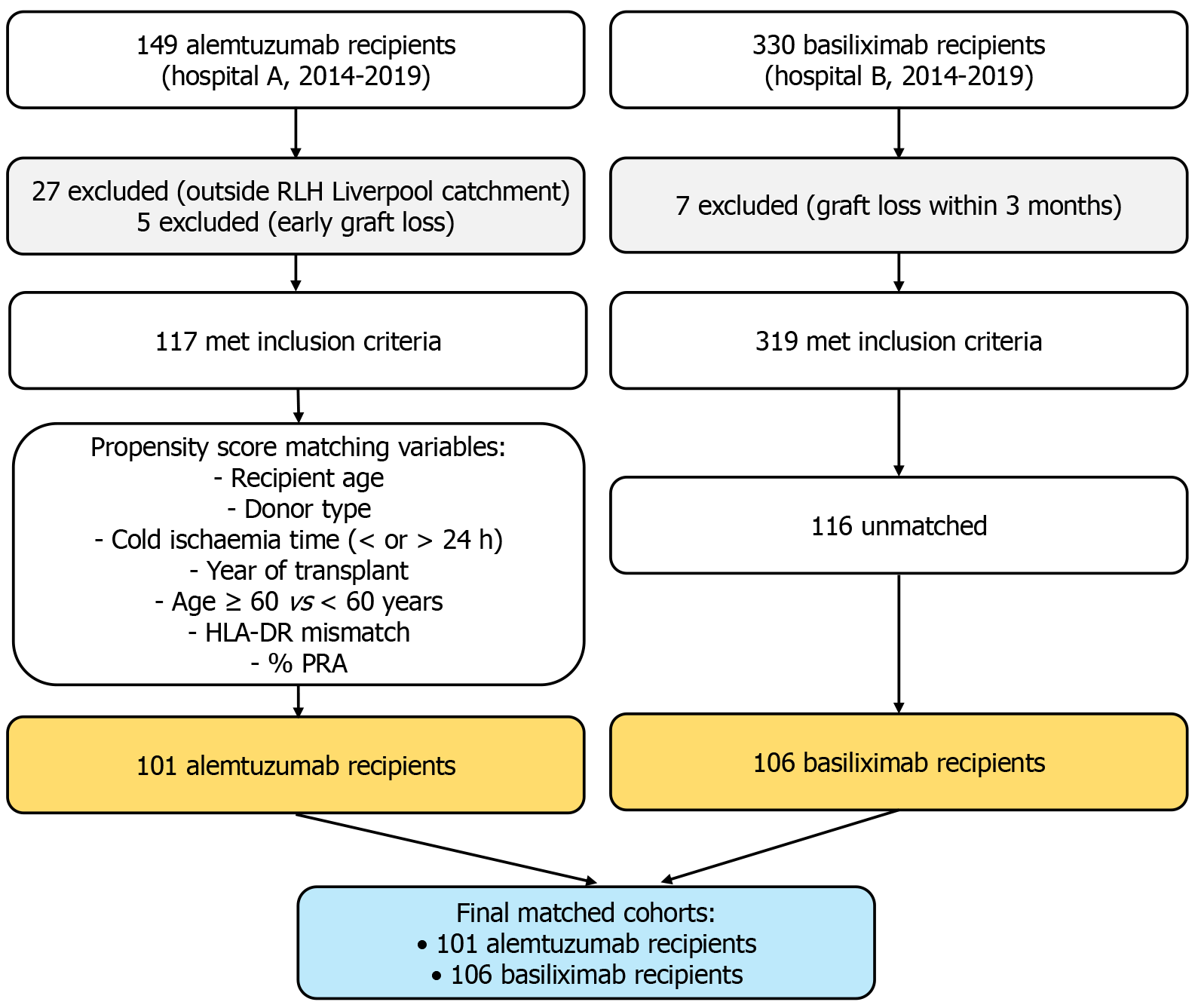

Between January 2014 and December 2019, a total of 665 patients underwent kidney transplantation across two hospitals, with 325 recipients from Hospital A and 330 from Hospital B. Among them, 149 recipients received alemtuzumab induction at Hospital A, while 329 received basiliximab induction at Hospital B. After excluding recipients who met the predefined exclusion criteria, 436 eligible recipients [basiliximab (n = 319), alemtuzumab (n = 117)] remained for PSM. Ultimately, 262 patients [alemtuzumab (n = 102) and basiliximab (n = 160)] were successfully matched. Twelve patients experienced early graft loss (< 3 months) and were excluded from the matched analysis [alemtuzumab (n = 5) and basiliximab (n = 7)]. The study flow and matching process are summarized in Figure 1.

The baseline characteristics of the recipients before propensity matching are shown in Supplementary Table 1, whereas the characteristics of the matched cohort are presented in Table 1, and the distribution of the outcome variables are shown in Table 2. The average age of the total cohort was 51.6 ± 14.2 years, which remained consistent at 51.1 ± 13.5 years in the matched cohort. The proportion of women was 38% in the total cohort and 39% in the matched cohort, with 80% of the total and 92% of the matched cohort being of white ethnicity. GN was the primary cause of kidney failure in 26% of both cohorts, while diabetic kidney disease occurred in 15% of the total and 13% of the matched cohort. The median follow-up period was 5.20 years (interquartile range: 4.17-6.20), during which 31 (7.1%) of the total cohort and 22 (8.4%) of the matched cohort experienced graft loss, and 37 (8.5%) of the total and 18 (6.9%) of the matched cohort died with functioning grafts.

| Variables | Basiliximab (n = 160) | Alemtuzumab (n = 102) | Total (n = 262) | P value |

| Age(years) [mean (SD)]1 | 51.1 (13.6) | 51.2 (13.4) | 51.1 (13.5) | 0.952 |

| Sex (female) | 62 (38.8) | 41 (40.2) | 103 (39.3) | 0.815 |

| Ethnicity1 | ||||

| White | 146 (91.2) | 96 (94.1) | 242 (92.4) | 0.773 |

| Asian | 10 (6.2) | 4 (3.9) | 14 (5.3) | |

| Black | 3 (1.9) | 1 (1.0) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Primary renal disease | ||||

| Adult polycystic kidney disease | 39 (24.2) | 14 (13.9) | 53 (20.2) | 0.048 |

| Glomerulonephritis | 42 (26.1) | 27 (26.7) | 69 (26.3) | |

| Diabetic kidney disease | 19 (11.8) | 14 (13.9) | 33 (12.6) | |

| Reflux/chronic pyelonephritis | 18 (11.2) | 14 (13.9) | 32 (12.2) | |

| Other | 28 (17.4) | 29 (28.7) | 57 (21.8) | |

| Unknown | 15 (9.3) | 3 (3.0) | 18 (6.9) | |

| Recipient diabetes | 28 (17.6) | 17 (17.3) | 45 (17.5) | 0.957 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) [mean (SD)] | 27.6 (4.4) | 27.0 (4.9) | 27.4 (4.6) | 0.318 |

| Pre-emptive transplant | 67 (41.9) | 20 (19.6) | 87 (33.2) | < 0.001 |

| Donor type1 | ||||

| Living donor | 63 (39.4) | 38 (37.3) | 101 (38.5) | 0.346 |

| Donation after brain death | 41 (25.6) | 20 (19.6) | 61 (23.3) | |

| Donation after circulatory death | 56 (35.0) | 44 (43.1) | 100 (38.2) | |

| Donor CMV | 93 (58.1) | 50 (49.0) | 143 (54.6) | 0.149 |

| Recipient CMV | 89 (55.6) | 51 (50.0) | 140 (53.4) | 0.373 |

| Recipient Epstein-Barr virus | 45 (90.0) | 87 (96.7) | 132 (94.3) | 0.103 |

| HLA-DR mismatch [mean (SD)]1 | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.7 (0.6) | 0.979 |

| Total HLA mismatch [mean (SD)]1 | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.6 (1.5) | 2.6 (1.4) | 0.987 |

| Crossmatch positive1 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0.738 |

| Pannel reactive antibodies [mean (SD)]1 | 22.4 (33.8) | 25.6 (35.8) | 23.7 (34.5) | 0.471 |

| Cold ischemia time1 | 11.0 (4.0-17.0) | 12.0 (5.0-15.0) | 11.5 (5.0-15.8) | 0.906 |

| Calcineurin inhibitor | ||||

| Tacrolimus | 156 (97.5) | 102 (100.0) | 258 (98.5) | 0.274 |

| Cyclosporin | 3 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Antimetabolite | ||||

| Mycophenolic acid | 150 (93.8) | 97 (95.1) | 247 (94.3) | 0.123 |

| Azathioprine | 9 (5.6) | 2 (2.0) | 11 (4.2) | |

| None | 1 (0.6) | 3 (2.9) | 4 (1.5) | |

| Steroid maintenance | 30 (22.2) | 22 (21.6) | 52 (21.9) | 0.904 |

| Baseline estimated glomerular filtration rate | 47.0 (36.0-57.0) | 43.0 (33.0-53.0) | 45.5 (35.0-54.8) | 0.093 |

| Outcomes | Basiliximab (n = 160) | Alemtuzumab (n = 102) | Total (n = 262) | P value |

| One-year estimated glomerular filtration rate | 53.5 (42.0-65.0) | 46.5 (34.0-54.8) | 50.0 (40.0-62.0) | < 0.001 |

| Cytomegalovirus viremia | 21 (13.2) | 31 (30.4) | 52 (19.9) | < 0.001 |

| Epstein-Barr virus viremia | 6 (3.8) | 11 (10.8) | 17 (6.5) | 0.025 |

| BK viremia | 18 (11.3) | 21 (20.6) | 39 (14.9) | 0.040 |

| Acute rejection throughout the follow up period | 10 (7.6) | 19 (18.6) | 29 (12.4) | 0.012 |

| Post-transplant glomerulonephritis | 5 (3.2) | 4 (3.9) | 9 (3.5) | 0.744 |

| Post transplant malignancy | 6 (4.3) | 12 (11.9) | 18 (7.5) | 0.027 |

In the pre-matched cohort, there was a higher proportion of white recipients in the Campath group compared to the Simulect group (94.9% vs 74.9%). However, after matching, the distribution of ethnicity became similar between the two groups, with a white majority (94.1% vs 91.2%). Pre-emptive transplantation was more common in the basiliximab group both before matching (39.8% vs 17.2%) and after matching (41.9% vs 19.6%). Additionally, basiliximab recipients exhibited a lower average PRA and a higher baseline eGFR.

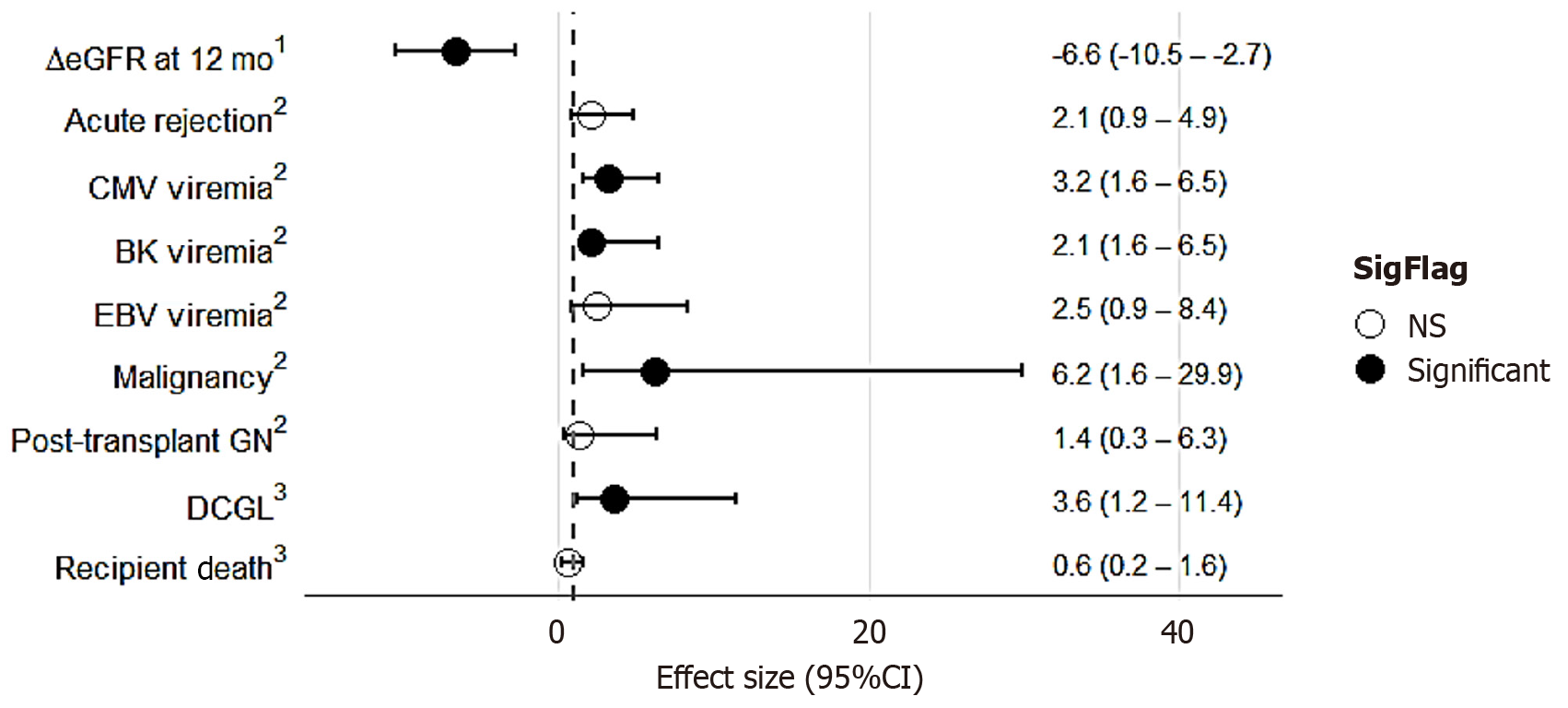

The treatment effects of alemtuzumab vs basiliximab were assessed across various outcome measures in the propensity-matched cohort, as depicted in Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 2. Recipients of alemtuzumab induction demonstrated a significantly lower eGFR at 12 months post-transplant compared with those who received basiliximab, with an adjusted mean difference of –6.6 mL/minute/1.73 m2 (95%CI: -10.5 to -2.7; P = 0.001), after adjustment for primary renal disease, baseline eGFR, pre-emptive transplantation, and propensity scores. Similarly, alemtuzumab induction was associated with a significantly higher risk of CMV viremia [odds ratio (OR) = 3.15; 95%CI: 1.58-6.48; P < 0.001] and BK viremia (OR = 2.40; 95%CI: 1.10-5.50; P = 0.024), following adjustment for pre-emptive transplantation, primary renal disease, donor and recipient CMV status, and propensity scores. In contrast, no significant difference was observed in the odds of Epstein-Barr virus viremia between the two groups. Furthermore, alemtuzumab induction was associated with a sixfold higher risk of post-transplant malignancy compared with basiliximab (OR = 6.17; 95%CI: 1.62-29.93; P = 0.013), after adjustment for age, pre-emptive transplantation, primary renal disease, and propensity scores. Finally, although the incidence of acute rejection was numerically higher among recipients of alemtuzumab, the difference did not reach statistical significance after adjustment for pre-emptive transplantation, PRA, and propensity scores (OR = 2.10; 95%CI: 0.88-4.93; P = 0.110).

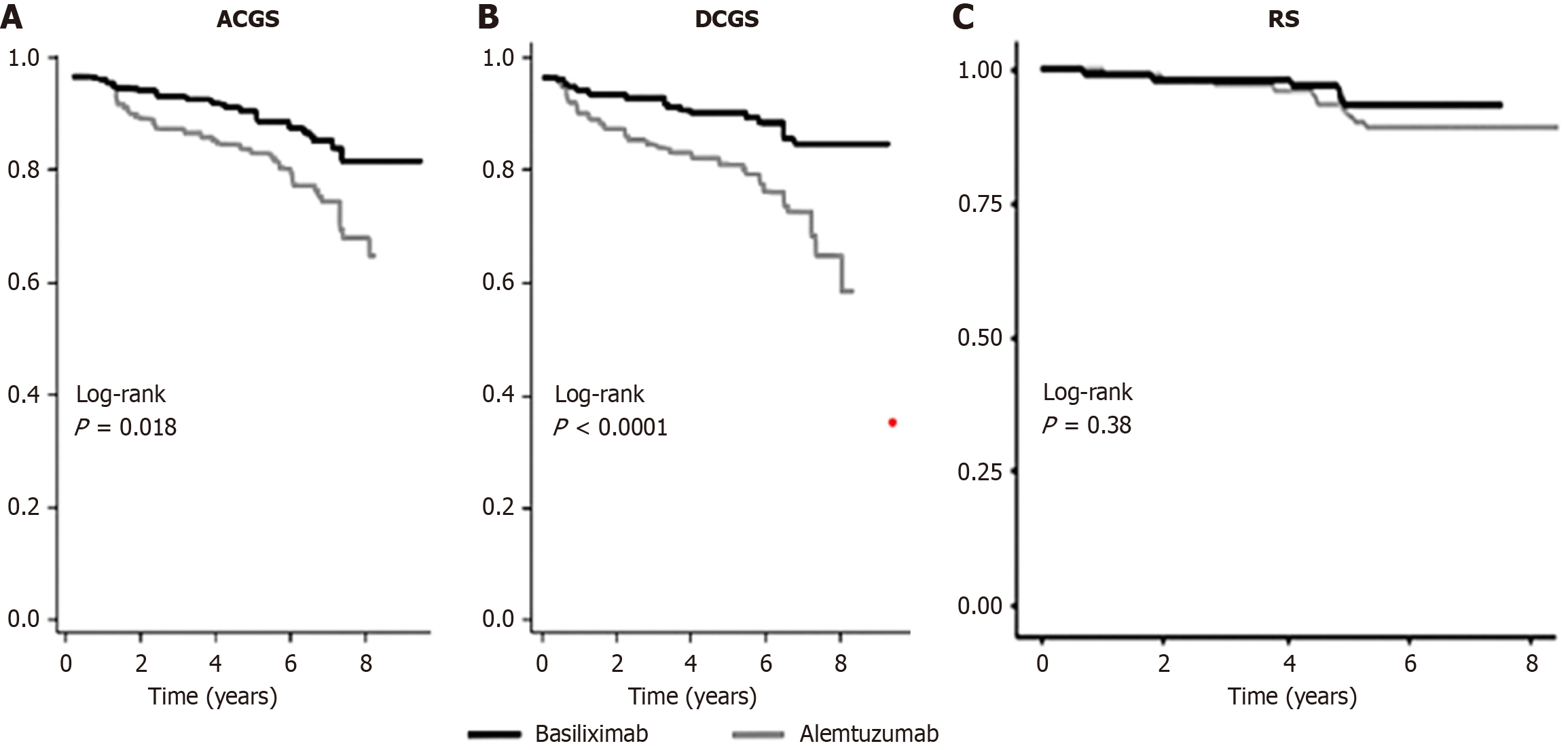

The hazard ratio (HR) of death-censored graft loss and recipient death is shown in Figure 2, whereas the all-cause graft survival, DCGS, and RS curves comparing alemtuzumab and basiliximab induction are presented in Figure 3. Alemtuzumab induction was associated with a significantly higher risk of death-censored graft loss compared with basiliximab (HR = 3.6; 95%CI: 1.2-11.4; P = 0.03). In contrast, no significant difference in overall RS was observed between the two groups (HR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.23-1.58; P = 0.31).

To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we performed sensitivity analyses using full matching as an alternative to the main propensity score greedy matching procedure. Effect estimates remained consistent across approaches, supporting the reliability of our main results (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Figure 2).

Comparisons between alemtuzumab and IL-2RA induction therapies in kidney transplantation have produced inconsistent results, often reflecting differences in study populations and follow-up durations. Assessing long-term outcomes has been particularly challenging because alemtuzumab is frequently reserved for higher-risk recipients, whereas basiliximab is widely used in standard-risk settings. Therefore, obtaining a cohort of recipients with comparable immunologic risks is difficult. By leveraging center-specific induction practices and applying PSM, our study was able to compare recipients with similar immunologic and demographic profiles. While prior investigations[6,7] have predominantly focused on short-term to medium-term outcomes (6-36 months)[11-14], our study's median follow-up duration of 62 months (5.2 years) provided valuable long-term insights.

Our findings indicate that alemtuzumab induction was associated with significantly lower eGFR at 12 months, a threefold higher risk of CMV viremia, a twofold higher risk of BK viremia, a sixfold higher risk of post-transplant malignancy, and inferior DCGS. In contrast, rates of acute rejection, post-transplant GN, and patient survival did not differ significantly.

The elevated risks of viral infections and malignancy are biologically plausible given alemtuzumab’s potent lymphocyte-depleting effects, which impair immune reconstitution and viral surveillance. Previous studies have reported mixed findings regarding infection risk[5,7,15]. The 3C study reported no difference in the occurrence of serious infections between alemtuzumab and basiliximab induction, including CMV viremia, but a higher BK virus infection in the alemtuzumab group[5] in the context of shorter follow-up and universal CMV prophylaxis. The 3C study may have underestimated later complications.

The higher incidence of malignancy is similarly consistent with impaired immune surveillance. The depletion of peripheral B cells and T cells, particularly regulatory T cells, in the early post-transplant period, followed by a skewed immune system reconstitution, may contribute to impaired viral surveillance and control mechanisms.

The decline in early graft function at 12 months parallels earlier reports and may reflect the cumulative impact of opportunistic infections, higher rates of chronic immunologic injury, and increased de novo donor-specific antibody formation associated with alemtuzumab[15-18]. These mechanisms[6,7,13] contribute to late immunological injury to the graft and likely contribute to the lower graft survival observed in our cohort, a finding also supported by several registry and single-center studies[19-23].

The effect on acute rejection remains less clear. Randomized controlled trials have reported both reduced[7,8,21] and similar[12,13,24] rates of rejection with alemtuzumab, and evidence suggests that any protective effect diminishes with time[7,16,25]. In our study, cumulative incidence over five years did not differ, but the absence of data on timing, type, severity, and treatment of rejection episodes limits interpretation. It remains possible that an early benefit may have been obscured.

To mitigate potential risks associated with alemtuzumab induction, alemtuzumab recipients often receive minimal exposure to corticosteroids and lower CNI trough levels, but the increased risk of cytopenias often leads to reduced or omitted antiproliferative agents. This may inadvertently increase long-term immunologic risk, particularly once lymphocyte reconstitution occurs after the first post-transplant year. Careful risk stratification and individualised immunosuppression adjustments are therefore crucial for these recipients.

Finally, treatment crossover complicates interpretation. In our cohort, more than one-third (42 of 117) of alemtuzumab recipients required prolonged steroids (≥ 6 months) within the first year, despite an intended steroid-free regimen (Supplementary Table 3). These recipients had a higher degree of HLA mismatch and a higher frequency of CMV viremia (48% vs 20%). It is worth noting, however, that this association between steroid use and occurrence of CMV viremia may partly reflect substitution of steroids for antiproliferative agents following CMV infection rather than preceding it. Nonetheless, such complexities highlight the challenges of long-term immunosuppression management and the importance of tailoring therapy to individual risk profiles.

In summary, our findings add to the evidence that alemtuzumab induction, while effective in some contexts, may be associated with increased risks of viral infections, malignancy, and inferior graft survival compared with basiliximab. These results underscore the need for cautious use, close monitoring, and future studies designed to disentangle the effects of induction therapy from subsequent treatment modifications.

The main strength of this retrospective investigation lies in its use of PSM, which enabled the identification of two cohorts of transplant recipients with comparable immunological and demographic profiles. This approach allowed a more balanced comparison of outcomes associated with alemtuzumab and basiliximab induction, thereby reducing confounding bias that has limited prior retrospective analyses.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective design also carries inherent limitations, including the risk of selection bias and incomplete data capture. Although PSM was employed to mitigate these concerns, residual confounding cannot be completely excluded[26].

Second, the matching process excluded a substantial proportion of patients from the original cohort, potentially reducing statistical power and limiting the generalizability of the findings. However, the use of the full matching method in the sensitivity analysis enabled all patients to be included by creating matched groups.

Third, the two-center design may introduce systematic bias related to institutional differences in clinical practice. While both centers adhered to National British Transplantation Society guidelines for key aspects of post-transplant management (including CNI trough level monitoring, infection prophylaxis, and rejection treatment), unmeasured differences, such as local antibiotic protocols, cardiovascular risk management strategies, and biopsy practices, may have influenced outcomes. These variations could have introduced residual confounding and should be considered when interpreting the results.

Fourth, the study period (2014-2019) coincided with evolving transplant practices, including refinements in immunosuppressive regimens and the implementation of a new kidney allocation scheme in the United Kingdom. Although these changes were unlikely to directly alter induction strategies, their potential impact on overall outcomes cannot be excluded.

Fifth, patients who experienced early graft loss (within three months post-transplantation) were excluded from the analysis. This decision was made to focus on long-term outcomes; however, because early graft failure may be influenced by the choice of induction agent, its exclusion could have underestimated risks associated with one or both agents. While the numbers were few and the characteristics of excluded patients were reported, this exclusion limits the interpretation of results, particularly regarding graft survival.

Additionally, detailed data on the timing, type, and severity of acute rejection episodes were not available, nor were histological assessments of chronic rejection or interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy, owing to the absence of routine protocol biopsies in both centers. This represents an important limitation in evaluating the full impact of induction therapy on graft durability.

Finally, changes in maintenance immunosuppression during follow-up were not systematically accounted for. These modifications, such as steroid reintroduction or adjustments in antiproliferative therapy, though difficult to capture in a retrospective analysis, may have influenced long-term outcomes and represent a potential source of confounding.

While no difference was observed in acute rejection rates, alemtuzumab induction was associated with several adverse outcomes, including inferior renal function, higher risks of viral infections and malignancy, and reduced graft survival compared with basiliximab induction. These findings highlight the need for careful long-term monitoring, risk stratification beyond the first post-transplant year, and individualized adjustments to maintenance immunosuppression in alemtuzumab recipients. Future prospective studies with extended follow-up will be required to validate these findings and provide stronger evidence to guide induction therapy choices in kidney transplantation.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the transplant teams, nephrology nursing staff, and data management personnel at both participating centers for their invaluable support in data collection and patient care. We also thank the clinical governance departments for facilitating access to institutional databases. The authors are particularly grateful to the patients whose clinical data made this study possible.

| 1. | Chukwu CA, Spiers HVM, Middleton R, Kalra PA, Asderakis A, Rao A, Augustine T. Alemtuzumab in renal transplantation. Reviews of literature and usage in the United Kingdom. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2022;36:100686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Afaneh C. Induction Therapy: A Modern Review of Kidney Transplantation Agents. J Transplant Technol Res. 2013;3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Klein CL. Selection of induction therapy in kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2013;26:662-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hwang SD, Lee JH, Lee SW, Park KM, Kim JK, Kim MJ, Song JH. Efficacy and Safety of Induction Therapy in Kidney Transplantation: A Network Meta-Analysis. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:987-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | 3C Study Collaborative Group; Haynes R, Harden P, Judge P, Blackwell L, Emberson J, Landray MJ, Baigent C, Friend PJ. Alemtuzumab-based induction treatment versus basiliximab-based induction treatment in kidney transplantation (the 3C Study): a randomised trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1684-1690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Welberry Smith MP, Cherukuri A, Newstead CG, Lewington AJ, Ahmad N, Menon K, Pollard SG, Prasad P, Tibble S, Giddings E, Baker RJ. Alemtuzumab induction in renal transplantation permits safe steroid avoidance with tacrolimus monotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Transplantation. 2013;96:1082-1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hanaway MJ, Woodle ES, Mulgaonkar S, Peddi VR, Kaufman DB, First MR, Croy R, Holman J; INTAC Study Group. Alemtuzumab induction in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1909-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pascual J, Pirsch JD, Odorico JS, Torrealba JR, Djamali A, Becker YT, Voss B, Leverson GE, Knechtle SJ, Sollinger HW, Samaniego-Picota MD. Alemtuzumab induction and antibody-mediated kidney rejection after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;87:125-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Von Stein L, Witkowsky O, Samidurai L, Doraiswamy M, Flores K, Pesavento TE, Singh P. Modification in induction immunosuppression regimens to safely perform kidney transplants amid the COVID-19 pandemic: A single-center retrospective study. Clin Transplant. 2021;35:e14365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ho DE, Imai K, King G, Stuart EA. MatchIt: Nonparametric Preprocessing for Parametric Causal Inference. J Stat Soft. 2011;42. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1461] [Cited by in RCA: 1462] [Article Influence: 97.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Knechtle SJ, Pascual J, Bloom DD, Torrealba JR, Jankowska-Gan E, Burlingham WJ, Kwun J, Colvin RB, Seyfert-Margolis V, Bourcier K, Sollinger HW. Early and limited use of tacrolimus to avoid rejection in an alemtuzumab and sirolimus regimen for kidney transplantation: clinical results and immune monitoring. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1087-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sampaio MS, Kadiyala A, Gill J, Bunnapradist S. Alemtuzumab versus interleukin-2 receptor antibodies induction in living donor kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2009;88:904-910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Safdar N, Smith J, Knasinski V, Sherkow C, Herrforth C, Knechtle S, Andes D. Infections after the use of alemtuzumab in solid organ transplant recipients: a comparative study. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;66:7-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hanaway M, Woodle ES, Mulgaonkar S, Peddi R, Harrison G, Vandeputte K, Fitzsimmons W, First R, Holman J. Final 36-month results of a multicenter, randomized trial comparing three induction agents (alemtuzumab, thymoglobulin and basiliximab) with tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil and a rapid steroid withdrawal in renal transplantation: 2689. Transplantation. 2010;90:19. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | LaMattina JC, Mezrich JD, Hofmann RM, Foley DP, D'Alessandro AM, Sollinger HW, Pirsch JD. Alemtuzumab as compared to alternative contemporary induction regimens. Transpl Int. 2012;25:518-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Todeschini M, Cortinovis M, Perico N, Poli F, Innocente A, Cavinato RA, Gotti E, Ruggenenti P, Gaspari F, Noris M, Remuzzi G, Casiraghi F. In kidney transplant patients, alemtuzumab but not basiliximab/low-dose rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin induces B cell depletion and regeneration, which associates with a high incidence of de novo donor-specific anti-HLA antibody development. J Immunol. 2013;191:2818-2828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jarmi T, Khouzam S, Shekhar N, Hosni M, White L, Hodge DO, Mai ML, Wadei HM. The Impact of Different Induction Immunosuppressive Therapy on Long-Term Kidney Transplant Function When Measured by Iothalamate Clearance. J Clin Med Res. 2020;12:787-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jarmi T, Abdelmoneim Y, Li Z, Jebrini A, Elrefaei M. Basiliximab is associated with a lower incidence of De novo donor-specific HLA antibodies in kidney transplant recipients: A single-center experience. Transpl Immunol. 2023;77:101778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ravindra KV, Sanoff S, Vikraman D, Zaaroura A, Nanavati A, Sudan D, Irish W. Lymphocyte depletion and risk of acute rejection in renal transplant recipients at increased risk for delayed graft function. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:781-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yakubu I, Ravichandran B, Sparkes T, Barth RN, Haririan A, Masters B. Comparison of Alemtuzumab Versus Basiliximab Induction Therapy in Elderly Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single-Center Experience. J Pharm Pract. 2021;34:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tanriover B, Zhang S, MacConmara M, Gao A, Sandikci B, Ayvaci MU, Mete M, Tsapepas D, Rajora N, Mohan P, Lakhia R, Lu CY, Vazquez M. Induction Therapies in Live Donor Kidney Transplantation on Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate With or Without Steroid Maintenance. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1041-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ciancio G, Gaynor JJ, Guerra G, Sageshima J, Chen L, Mattiazzi A, Roth D, Kupin W, Tueros L, Flores S, Hanson L, Vianna R, Burke GW 3rd. Randomized trial of three induction antibodies in kidney transplantation: long-term results. Transplantation. 2014;97:1128-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tanriover B, Jaikaransingh V, MacConmara MP, Parekh JR, Levea SL, Ariyamuthu VK, Zhang S, Gao A, Ayvaci MUS, Sandikci B, Rajora N, Ahmed V, Lu CY, Mohan S, Vazquez MA. Acute Rejection Rates and Graft Outcomes According to Induction Regimen among Recipients of Kidneys from Deceased Donors Treated with Tacrolimus and Mycophenolate. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11:1650-1661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ciancio G, Burke GW, Gaynor JJ, Roth D, Kupin W, Rosen A, Cordovilla T, Tueros L, Herrada E, Miller J. A randomized trial of thymoglobulin vs. alemtuzumab (with lower dose maintenance immunosuppression) vs. daclizumab in renal transplantation at 24 months of follow-up. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:200-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sureshkumar KK, Thai NL, Hussain SM, Ko TY, Marcus RJ. Influence of induction modality on the outcome of deceased donor kidney transplant recipients discharged on steroid-free maintenance immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2012;93:799-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Austin PC. A comparison of 12 algorithms for matching on the propensity score. Stat Med. 2014;33:1057-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 743] [Cited by in RCA: 753] [Article Influence: 62.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/