Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v15.i4.105732

Revised: February 27, 2025

Accepted: April 15, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 286 Days and 13.7 Hours

Heart transplantation is the last and best option for end-stage heart failure management. Early mortality rates have significantly decreased, enabling patients to survive longer with fewer complications, a trend observed even in our setting. The primary shared challenge has centered on achieving surgical success and immediate survival. The question arises about the medium- and long-term sur

To present the results of the medium and long-term follow-up of heart transplant patients.

This was a retrospective study of a single medical unit, and we selected patients who received heart transplants from July 21, 1988 to September 30, 2023. Selection criteria encompassed age, sex, and primary indication for heart transplantation across all groups. Patients with incomplete information or who died within 30 postoperative days were excluded. Data of primary pathology, ischemic, extracorporeal circulation, aortic cross-clamping times, length of ventilatory support, stay in postoperative therapy, hospitalization, and functional class were analyzed.

The causes of morbidity, mortality, and percentage of survival at 1, 5, and 10 years were examined. Overall, 257 heart transplants were performed during the study period. Of the total cases, 22 with incomplete data and 47 who died within 30 postoperative days were excluded for the middle- and long-term survival analyses. Of the remaining 188 patients, heart transplantation was performed (males: 146, females: 42). The average age of the participants was 44.43 ± 14.48 years. The primary indications included ischemic cardiomyopathy (42.55%) and dilated cardiomyopathy (39.36%). The mean durations of mechanical ventilator support, intensive care stay, and hospital stay were 57.55 ± 103.50 hours, 9.96 ± 8.59 days, and 19.49 ± 18.23 days, respectively. One-, five-, and ten-year survival rates were 90.7%, 71.3%, and 60.3%, respectively. Of the patients, 94% and 6% were in functional classes I and II, respectively. Infection and neur

In our setting, heart transplantation yields medium- and long-term survival and quality of life outcomes comparable to those achieved by other international centers.

Core Tip: In Mexico, ensuring surgical success and immediate survival in heart transplantation recipients constitute a significant challenge. The dilemma arises regarding the medium- and long-term survival of patients receiving heart transplant. The results of this review revealed 1- and 5-year survival rates of 90% and 71%, respectively. Notably, globally, current selection criteria for heart transplant candidates now include patients who were previously deemed ineligible. Adapting short- and long-term treatment and management protocols will be necessary.

- Citation: Careaga-Reyna G, Zetina-Tun HJ. Middle- and long-term survival of patients with heart transplant in Mexico from 1988 to 2023: A group experience. World J Transplant 2025; 15(4): 105732

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v15/i4/105732.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v15.i4.105732

Despite advances in knowledge and new treatment strategies for heart failure, heart transplantation remains to be the last and best option for managing end-stage heart failure in appropriately selected patients refractory to other options and/or with contraindications for mechanical circulatory support[1]. Heart transplantation has demonstrated its benefits since the first case performed in South Africa by Christian Barnaard in 1967[1-3]. Initially, immunosuppressive therapy represented the biggest challenge; in 1974, Graham et al[4] reported survival at 43% post-transplant and 3-year survival at 26%. The introduction of novel immunosuppressive drugs, including cyclosporine[5], has significantly improved the control over this this condition, complemented by advancements in perioperative care and the use of ventricular support devices for primary graft failure. Early mortality rates have substantially decreased, enabling longer survival with fewer complications, a trend noted even in our setting[5-8].

Under these conditions, on July 21, 1988, Argüero et al[8] successfully performed the first heart transplant in Mexico - a watershed in national medicine - a beginning that has been consolidated for more than 30 years, with the development of various centers in which this procedure is performed in our country[3,9]. Several heart transplant programs, each with varying levels of experience, productivity, and outcomes, have been implemented in Mexico. The significant shared challenge has focused on ensuring surgical success and immediate survival[3], which undoubtedly depends on the subsequent stage; therefore, following the perioperative stage, patient control is crucial for ensuring and maintaining the expected benefit of heart transplantation in enhancing survival and quality of life. Therefore, the dilemma arises regarding the medium- and long-term survival of patients receiving heart transplant in our setting at > 35 years following the onset of the longest-running heart transplantation program in Mexico[3], which is also the program with the highest productivity, and with patients in medium- and long-term follow-up. Global advancements in heart transplantation have led to improved long-term outcomes, expanding eligibility to patients with various medical conditions previously deemed unsuitable for transplant programs[6,9]. We aimed to present the experience and insights acquired by a medical unit with the longest-standing and most established heart transplantation program in Mexico.

We present the cases of patients with terminal heart failure regardless of the etiology, who have undergone heart transplantation or heart transplantation combined with other organs, who have not died in the perioperative period between surgery and the first 30 days post-transplant, in a high specialty medical unit from July 21, 1988 to September 30, 2023. Inclusion criteria comprised patients of all age groups, both sexes, and primary indication for heart transplantation. Patients with incomplete data or who died within 30 days postoperatively were excluded. The variables of age, sex, and primary pathology were analyzed. Moreover, the ischemia time from the time of aortic cross-clamping was performed for heart extraction in the donor, until aortic clamp removal and the initiation of reperfusion once placed in the recipient, the time in which the recipient was maintained with the support of extracorporeal circulation expressed in minutes and the time of aortic cross-clamping in the recipient also reported in minutes. The duration of mechanical ventilation (in hours), length of stay in the postoperative care unit and hospital (in days), and functional class according to the New York Heart Association classification were evaluated. Furthermore, the causes of morbidity and mortality from 30 days postoperatively and long-term follow-up; survival rates at 1, 5, and 10 years; complications; treatments performed; and the occurrence of events requiring special care during follow-up due to special conditions and their evolution were analyzed. Descriptive statistics with measures of central tendency and dispersion were employed for characterizing the sample.

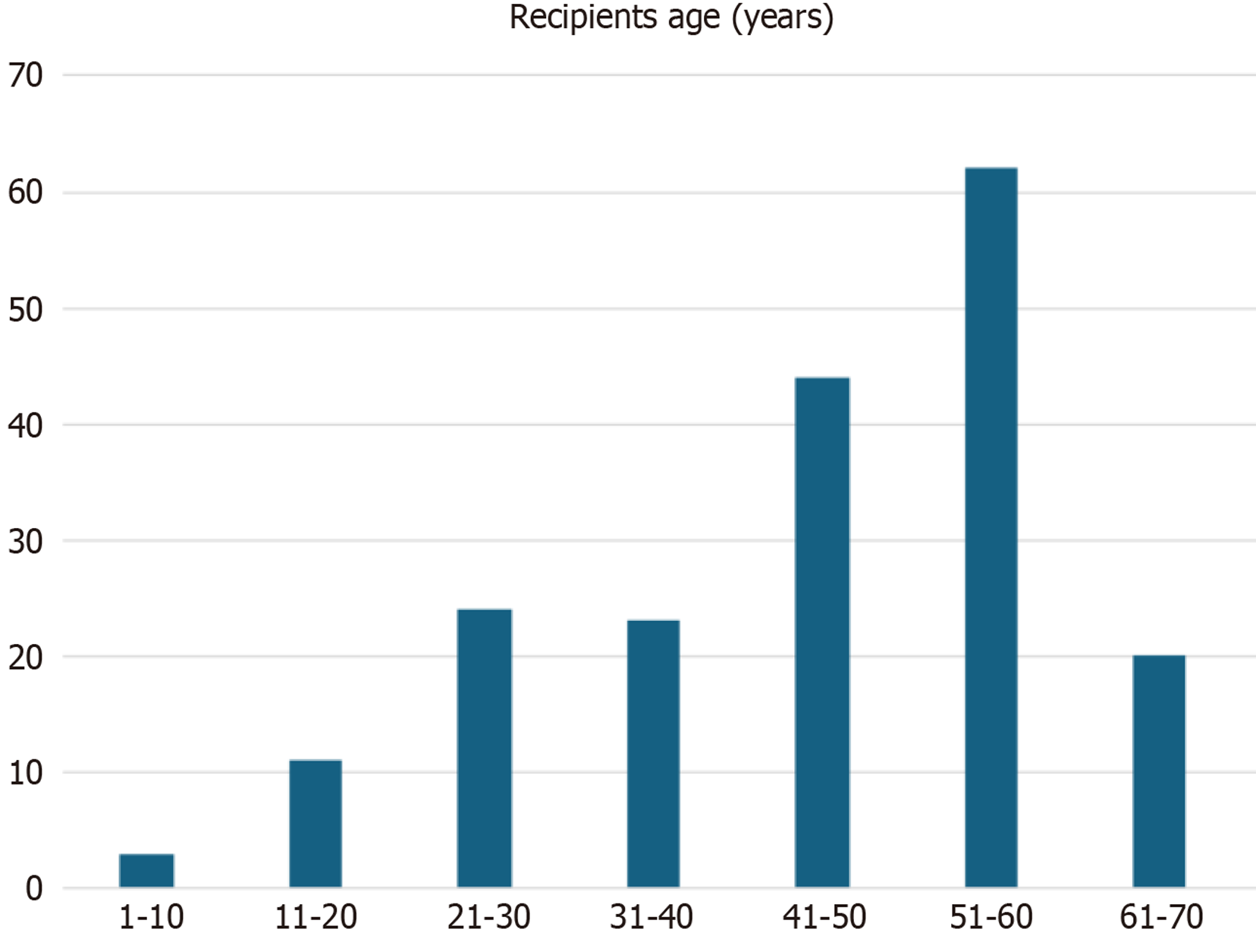

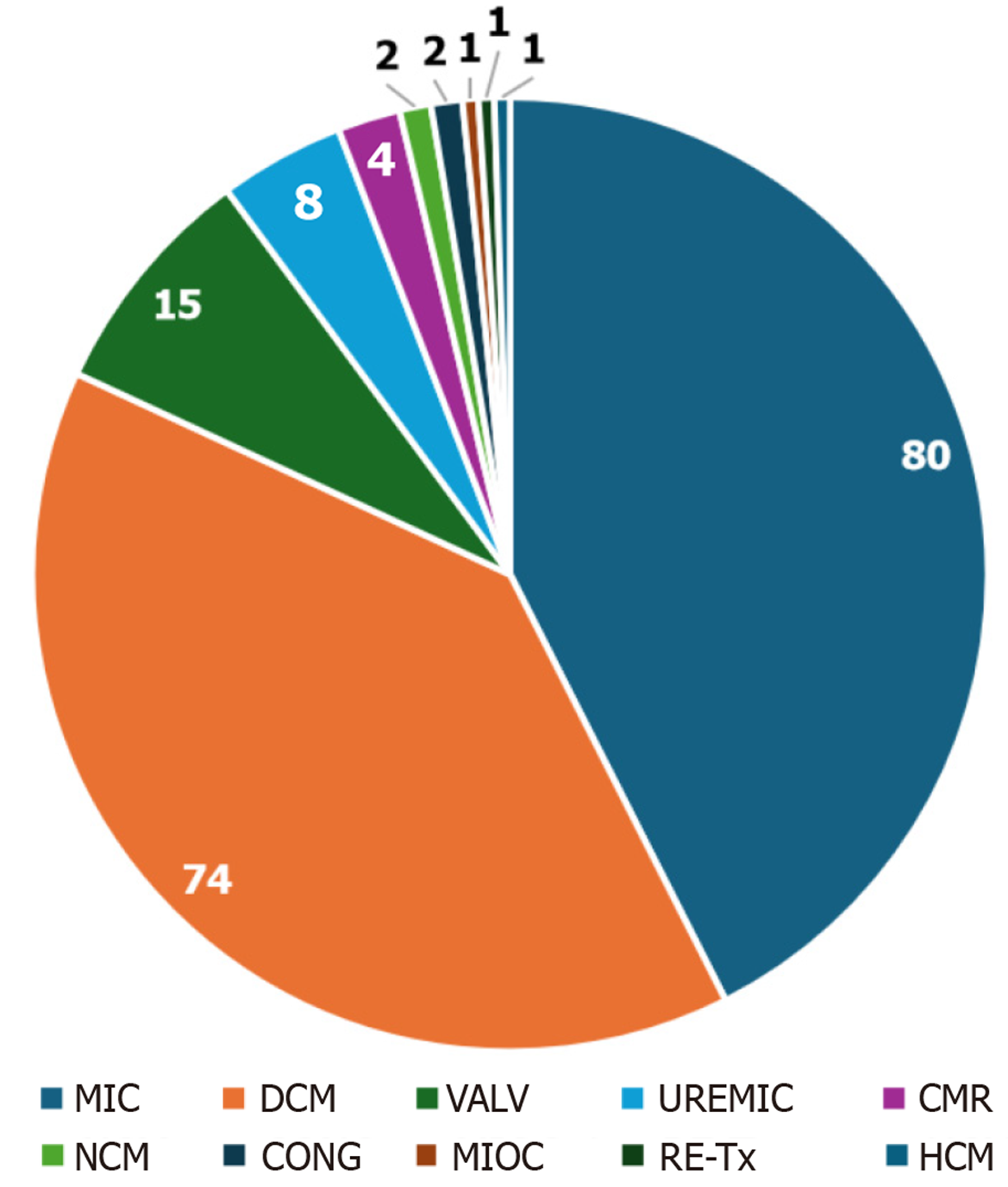

During the study period, 257 heart transplants were performed at this hospital, 188 of which survived for ≥ 30 days. There were 146 males and 42 females, with a mean age of 44.43 ± 14.48 (range 8-66) years (Figure 1). Forty-seven patients who died within 30 postoperative days and twenty-two with incomplete data were excluded from the final analysis. The primary indications encompassed ischemic and dilated cardiomyopathies with 80 (42.55%) and 74 (39.36%) patients, respectively; of two patients with Chagas disease, one had dilated cardiomyopathy due to inclusion antibodies, and the other due to propionic acidemia. Fifteen patients had valvular cardiomyopathy, and eight patients had uremic cardiomyopathy, in addition to congenital heart disease, noncompacted myocardium, and graft vasculopathy (chronic rejection), which was a treatment-refractory case that necessitated the first elective heart retransplantation case in our setting in 2017 (Figure 2). Here, it is relevant to comment on the start of the orthotopic heart transplantation program combined with kidney transplantation, which is the only one that exists in Mexico with eight cases performed during this review.

The following were the procedures performed: 180 orthotopic (41 using the conventional biauricular technique described by Lower and Shumway and 139 using the bicaval technique). In 1991, the first heart transplant on pediatric patients was conducted in Mexico, marking a significant milestone in the medical history of this country. From April 1995 to September 2006, eight heterotopic transplants were realized. On November 16, 2004, the first transplant using the bicaval technique was performed, which has been regularly developed thereafter, except for one case in 2023, wherein performing the transplant using the bicaval technique was necessary owing to the left vena cava draining into the coronary sinus. The procedure was performed without any complications. Table 1 presents the ischemia time, duration of support with extracorporeal circulation, and time of aortic cross-clamping of the patients. From 1988 to 1996, heart preservation for transplantation involved hypothermia and infusion of modified St. Thomas extracellular cardioplegic solution during procurement and implantation, with 20-minutes intervals. Subsequently, since 1996, myocardial protection was performed using Bretschneider’s solution (intracellular cardioplegia histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate), with a single dose of 30 mL/kg of the donor weight during heart extraction and hypothermia.

| Time | Duration, minutes |

| Ischemic period | 230.36 ± 57.97 (range 95-368) |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 147.12 ± 39.07 (range 69-290) |

| Aortic cross-clamping | 84.49 ± 15.51 (range 56-134) |

The initial immunosuppressive regimen comprised cyclosporine, azathioprine, and steroids. With the introduction of novel immunosuppressants, the regimen was modified, and cyclosporine and azathioprine were replaced by myco

The mean durations of mechanical ventilator support, intensive care stay, and hospital stay were 57.55 ± 103.50 (range 4-648) hours, 9.96 ± 8.59 (range 3-50) days, and 19.49 ± 18.23 (range 2-118) days, respectively. The longer durations of ventilatory support, intensive care stay, and hospital stay were due to perioperative complications (renal failure, mechanical ventilation-associated pneumonia, and reoperations due to excessive bleeding) that required further interventions. One-, five-, and ten-year survival rates were 90.7%, 71.3%, and 60.3%, respectively. A recipient, who is in his second year of post-transplant survival, received a heart from a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive donor and is currently surviving without complications. Of the included patients, 94% and 6% had New York Heart Association functional classes I and II, respectively.

At 1 year following transplantation, the primary cause of mortality was infection, particularly pneumonia (21%), followed by abdominal sepsis (13%) and ischemic and hemorrhagic neurological events (26%). Predominating the ischemic etiology were three cases with acute rejection, one of them was due to immunosuppressive therapy suspension by the patient. Following 1-year post-transplantation, the frequency of infectious complications decreased as a cause of mortality, whereas the frequency of chronic rejection manifesting as graft vasculopathy increased as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality (30%). Of these identified patients, four had sudden death, and six were treated with percu

The benefits of organ transplantation in enhancing life expectancy and quality of life for patients with terminal and irreversible organ failure have been well-established throughout the development of transplant programs worldwide. The success of the procedure is observed from the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods; however, ischemia-reperfusion, acute rejection, graft failure, and other surgical intervention-associated complications can be life-threatening. Fortunately, with advances in perioperative care, these complications occur less frequently and enable improved patient survival[6]. However, for the purpose of middle- and long-term survival analyses, we decided to exclude early mortality on the basis that perioperative deaths may occur, as previously described. In our series, primary graft failure mainly in the earlier stage of the heart transplantation program was the main cause of perioperative mortality.

Therefore, during medium- and long-term care, other complications may arise that jeopardize the success of the transplant, including chronic rejection, immunosuppressive therapy-related complications, and concurrent diseases that may be asymptomatic. Therefore, follow-up protocols should be implemented, including multidisciplinary follow-up with dermatologists and oncologists, periodic control with endomyocardial biopsy[6,9], and in cases, as in this series, wherein a patient was pregnant in the middle-term follow-up, the participation of obstetricians and perinatologists for joint care where the immunosuppressive regimen, the monitoring of product development, and the function of the transplanted heart are involved[3]. The timely detection of graft vasculopathy has enabled the development of ther

The results of this review were obtained from only a single medical unit in Mexico, which has the longest-running and most established heart transplantation program in the country. Of the heart transplants realized in Mexico from July 21, 1988 to September 30, 2023, 30% were performed in this medical unit[3], with 1- and 5-year survival rates of 90% and 71%, respectively, which favorably contrasts with the review by Gupta and Krim[1], who in the same time periods reported 1- and 5-year survival rates of 84.5% and 72.5%, respectively[12]. However, in Mexico, owing to the local regulations of other medical units with heart transplantation programs, their complete database is not available for comparing their outcomes or developing a complete registry of the heart transplant programs. The etiologies of mortality are similar to those reported worldwide. In the early post-transplant period, infections and neurological complications are predominant, whereas graft vasculopathy emerges as the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the later stages[1,3,12]. Currently, the association of terminal failure of two or more organs that initially contraindicated heart transplantation can be managed with combined organ transplantation with careful evaluation. Such is the case of heart-kidney transplantation, a program that is developed with characteristics and results similar to those reported worldwide[3,13].

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic significantly affected the follow-up care of these patients, leading to wide

Our medium- and long-term follow-up results reveal that heart transplant patients experience life expectancy and quality of life comparable to other reported series, confirming heart transplantation as a viable therapeutic alternative with sustained benefits in our setting.

| 1. | Gupta T, Krim SR. Cardiac Transplantation: Update on a Road Less Traveled. Ochsner J. 2019;19:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Barnard CN. The operation. A human cardiac transplant: an interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 1967;41:1271-1274. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Careaga-Reyna G. Experience acquired after 34 years of the first heart transplantation in Mexico. Gac Med Mex. 2023;159:69-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Graham AF, Rider AK, Caves PK, Stinson EB, Harrison DC, Shumway NE, Schroeder JS. Acute rejection in the long-term cardiac transplant survivor. Clinical diagnosis, treatment and significance. Circulation. 1974;49:361-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | DiBardino DJ. The history and development of cardiac transplantation. Tex Heart Inst J. 1999;26:198-205. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Costanzo MR, Dipchand A, Starling R, Anderson A, Chan M, Desai S, Fedson S, Fisher P, Gonzales-Stawinski G, Martinelli L, McGiffin D, Smith J, Taylor D, Meiser B, Webber S, Baran D, Carboni M, Dengler T, Feldman D, Frigerio M, Kfoury A, Kim D, Kobashigawa J, Shullo M, Stehlik J, Teuteberg J, Uber P, Zuckermann A, Hunt S, Burch M, Bhat G, Canter C, Chinnock R, Crespo-Leiro M, Delgado R, Dobbels F, Grady K, Kao W, Lamour J, Parry G, Patel J, Pini D, Towbin J, Wolfel G, Delgado D, Eisen H, Goldberg L, Hosenpud J, Johnson M, Keogh A, Lewis C, O'Connell J, Rogers J, Ross H, Russell S, Vanhaecke J; International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:914-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1100] [Cited by in RCA: 1237] [Article Influence: 77.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jorde UP, Saeed O, Koehl D, Morris AA, Wood KL, Meyer DM, Cantor R, Jacobs JP, Kirklin JK, Pagani FD, Vega JD. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2023 Annual Report: Focus on Magnetically Levitated Devices. Ann Thorac Surg. 2024;117:33-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Argüero R, Castaño R, Portilla E, Sánchez O, Molinar F. [Primer Caso de Trasplante de Corazón en México]. Rev Med Inst Mex Seg Soc. 1989;26:107-112. |

| 9. | Peled Y, Ducharme A, Kittleson M, Bansal N, Stehlik J, Amdani S, Saeed D, Cheng R, Clarke B, Dobbels F, Farr M, Lindenfeld J, Nikolaidis L, Patel J, Acharya D, Albert D, Aslam S, Bertolotti A, Chan M, Chih S, Colvin M, Crespo-Leiro M, D'Alessandro D, Daly K, Diez-Lopez C, Dipchand A, Ensminger S, Everitt M, Fardman A, Farrero M, Feldman D, Gjelaj C, Goodwin M, Harrison K, Hsich E, Joyce E, Kato T, Kim D, Luong ML, Lyster H, Masetti M, Matos LN, Nilsson J, Noly PE, Rao V, Rolid K, Schlendorf K, Schweiger M, Spinner J, Townsend M, Tremblay-Gravel M, Urschel S, Vachiery JL, Velleca A, Waldman G, Walsh J. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the Evaluation and Care of Cardiac Transplant Candidates-2024. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2024;43:1529-1628.e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Leite L, Matos V, Gonçalves L, Silva Marques J, Jorge E, Calisto J, Antunes M, Pego M. Heart transplant coronary artery disease: Multimodality approach in percutaneous intervention. Rev Port Cardiol. 2016;35:377.e1-377.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mehra MR, Crespo-Leiro MG, Dipchand A, Ensminger SM, Hiemann NE, Kobashigawa JA, Madsen J, Parameshwar J, Starling RC, Uber PA. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation working formulation of a standardized nomenclature for cardiac allograft vasculopathy-2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29:717-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 787] [Cited by in RCA: 724] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, Benden C, Christie JD, Dipchand AI, Dobbels F, Goldfarb SB, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Yusen RD, Stehlik J; International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation. The registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: thirty-first official adult heart transplant report--2014; focus theme: retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:996-1008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 36.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khush KK, Cherikh WS, Chambers DC, Goldfarb S, Hayes D Jr. , Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, Meiser B, Rossano JW, Stehlik J; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-fifth Adult Heart Transplantation Report-2018; Focus Theme: Multiorgan Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1155-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Martinez-Reviejo R, Tejada S, Cipriano A, Karakoc HN, Manuel O, Rello J. Solid organ transplantation from donors with recent or current SARS-CoV-2 infection: A systematic review. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2022;41:101098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Secretaria de Salud. Plan de reactivación de los programas de donación y trasplantes ante la epidemia del virus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) en México. [cited 30 December 2024]. Available from: https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/756875/22-08-26_PLAN_de_reactivacion_de_los_programas_de_donaci_n_y_trasplantes.pdf. |

| 16. | Zetina-Tun HJ, Careaga-Reyna G, Galván-Díaz J, Sánchez-Uribe M. Heart transplantation for the treatment of isolated left ventricular myocardial noncompaction. First case in Mexico. Cirugía y Cirujanos (English Edition). 2017;85:539-543. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Careaga-Reyna G, Zetina-Tun HJ, Arizmendi-Uribe E. Heart transplantation in patients with type II diabetes Mellitus. Rev Arg Cir Card. 2024;22:3-6. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Clark S. Ethical considerations in controlled donation after circulatory death. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;14:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang L, Cain MT, Minambres E, Hoffman JRH, Berman M. Thoracoabdominal normothermic regional perfusion-approaches to arch vessels and options of cannulation allowing donation after circulatory death multi-organ perfusion and procurement. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;14:70-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Boffini M, Gerosa G, Luciani GB, Pacini D, Russo CF, Rinaldi M, Terzi A, Pelenghi S, Luzi G, Zanatta P, Zanierato M, Sacchi M, Bottazzi A, Tarzia V, Onorati F, Pellegrini C, Suarez SM, Mondino M, Lilla Della Monica P, Nanni A, Marro M, Oliveti A, Feltrin G, Cardillo M. Heart transplantation in controlled donation after circulatory determination of death: the Italian experience. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;14:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Jolliffe J, Brookes J, Williams M, Walker E, Jansz P, Watson A, MacDonald P, Smith J, Bennetts J, Boffini M, Loforte A. Donation after circulatory death transplantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes and methods of donation. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;14:11-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/