Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113533

Revised: November 4, 2025

Accepted: December 4, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 111 Days and 22.7 Hours

Women are susceptible to anxiety and depression during pregnancy, but the temporal patterns of these emotions across gestation remain unclear. It is also uncertain whether anxiety and depression during pregnancy exert time-lagged effects on postpartum depression.

To explore the dynamic trends of anxiety and depression at different stages of pregnancy and their time-lagged effects on postpartum depression, providing a reference for emotional management during and after pregnancy.

Data were collected from 572 women who underwent prenatal care and delivered at the Obstetrics Department of Suzhou Ninth People’s Hospital between January 2024 and June 2025. The χ2 test was used to assess psychologically changes from early to late pregnancy. Pearson partial correlation and cross-lagged modeling were used to examine temporal relationships between prenatal anxiety/depre

Anxiety detection rates were 6.99% (40/572) in early pregnancy, 24.13% (138/572) in midpregnancy, and 16.96% (97/572) in late pregnancy, showing a significant fluctuation trend (χ2 = 21.092, P < 0.001). Depression rates were 5.42% (31/572), 21.68% (124/572), 13.81% (79/572) and 16.08% (92/572) in early, mid, late preg

Anxiety and depression during pregnancy demonstrate dynamic evolution and both have time-lagged predictive effects on postpartum depression.

Core Tip: Hormonal fluctuations, anatomical changes, and evolving family roles during pregnancy often disrupt women’s physical and emotional balance, leading to mental health challenges. This study revealed that fluctuations in anxiety and depressive emotions at different gestational stages have time-lagged associations with postpartum depression, offering a new insight for clinical management of maternal emotional health during and after pregnancy.

- Citation: Gao YP, Lu YY. Time series analysis of anxiety and depression during pregnancy to postpartum depression based on cross-lagged model. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 113533

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/113533.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113533

Postpartum depression typically manifests within six weeks after delivery as a major maternal mental health concern. Affected women often experience anxiety, pain, fear, and cognitive or behavioral changes; in severe cases, self-harm or infanticide behavior may occur, drawing considerable attention from obstetric and clinical psychologists[1]. Pregnancy is a unique physiological and psychological period. Hormonal changes, anatomical changes, and shifts in family roles can disrupt women’s physical and emotional balance, predisposing them to various physical and psychological symptoms. A global meta-analysis reported a prevalence of anxiety symptoms during pregnancy of 18.2%[2], while a meta-analysis of the Chinese population found detection rates of depressive symptoms during pregnancy and postpartum of 19.7% and 14.8% respectively[3]. These findings highlight the high incidence of anxiety and depression among pregnant and postpartum women. Adverse psychological states during pregnancy can negatively affect pregnancy outcomes, including premature birth and low birth weight[4]. Postpartum mental distress may impair mother-infant bonding and feeding, hinder emotional attachment, and even impact infant’s cognitive and emotional development[5]. However, most existing studies rely on cross-sectional designs and treat adverse psychological states during pregnancy (e.g., prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety) and postpartum (e.g., postpartum depression, postpartum anxiety) as independent variables, overlooking their high comorbidity and overlapping symptoms throughout the perinatal period. Analysis limited to a single time point cannot capture the dynamic evolution and systematic interaction of anxiety and depression from pregnancy through postpartum. The cross-lagged model can describe the predictive influence of one variable over another across time, and has been applied to relationships such as perinatal health-related quality of life and attitudes toward breastfeeding and between perinatal depression symptoms and breastfeeding[6,7]. However, the dynamic trajectory linking prenatal anxiety and depression to postpartum depression remains largely unexplored. This study systematically investigated these trajectories, using early, mid, and late pregnancy, as well as 6-week postpartum as observation nodes. By applying a cross-lagged model to construct a cross-time-point pathway, this study aimed to elucidate the interaction patterns between depression and anxiety across pregnancy and postpartum, offering new insights for emotional management and clinical intervention in perinatal women.

This retrospective study included 572 women who received prenatal care and delivered at the Obstetrics Department of Suzhou Ninth People’s Hospital, between January 2024 and June 2025.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 18 years old; (2) Single pregnancy with both prenatal checkups and delivery completed at the study hospital; (3) Planned pregnancy; (4) Ability to communicate normally in speech and writing; (5) Live-born infants without deformities; and (6) Availability of psychological health screening data at four time points: Early pregnancy, midpregnancy, late pregnancy, and six weeks postpartum.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Prior diagnosis of mental illness before pregnancy; (2) History of recurrent spontaneous abortion; (3) Severe pregnancy complications (e.g., preeclampsia, placental abruption); (4) Presence of malignancy; (5) Serious postpartum complications (e.g., infection, postpartum hemorrhage); and (6) Medical disputes with the hospital.

General information collection: A standardized questionnaire was used to gather demographic and obstetric data, including age, educational level, residence, gravidity, parity, delivery status (prematurity and delivery method), newborn sex, and birth weight.

Mental health screening during pregnancy: Psychological status during pregnancy was assessed retrospectively using hospital records at four time-points (early, mid, and late pregnancy, as well as six weeks postpartum). Anxiety was measured using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale 7 (GAD-7)[8], comprising seven items rated on a 4-point scale: 0 = “not at all”, 1 = “several days”, 2 = “over 1 week”, and 3 = “almost every day”, totaling 0-21 points. Scores ≥ 5 indicated anxiety symptoms, with < 5 points indicating no anxiety symptoms, 5-9 indicating mild anxiety, 10-14 indicating moderate anxiety, and 15-21 severe anxiety. Depression was evaluated using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9)[9], comprising nine items rated similarly on a 4-point scale, including “not at all” (0 point), “several days” (1 point), “over 1 week” (2 points), and “almost every day” (3 points), totaling 0-27 points. Scores ≥ 5 points indicated depressive symptoms, classified as mild (5-9), moderate (10-14), or severe (15-27).

Postpartum mental health screening: At six weeks postpartum, participants underwent psychological evaluation during their routine obstetric follow-up using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), comprising 10 items assessing mood, pleasure, crying, self-blame, self-injury, sadness, depression, coping ability, fear, and insomnia. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale: 0 = “never”, 1 = “occasionally”, 2 = “frequently”, and 3 = “always”, totaling 0-30 points. Scores ≥ 9 indicated postpartum depressive symptoms[10], with higher scores reflecting greater severity. Specifically, < 9 points indicated no postpartum depressive symptoms, 9-12 points indicated mild postpartum depression, 13-15 points indicated moderate postpartum depression, and 16-30 points indicated severe postpartum depression.

All data analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0. Quantitative variables were first tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test and expressed as mean ± SD. Categorical variables were presented as n (%). When comparing scores across different scales, Z-score standardization was applied. The Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test was used to assess the trend of anxiety and depression incidence across pregnancy and postpartum stages. Pearson correlation analysis evaluated associations between depression and anxiety screening scores at different time points. A cross-lagged model was constructed using Amos version 23.0 to analyze the path relationships between maternal anxiety, depression during pregnancy, and postpartum depression. Statistical significance was set at α = 0.05, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Among the 572 participants, ages ranged from 20 to 39 years, with a mean of 28.93 ± 5.26 years. Long-term urban residents accounted for 52.27%, whereas 49.83% had completed high school or vocational education. Women with < 3 prior pregnancies comprised 61.01%, and those with < 2 prior deliveries accounted for 65.91%. The proportion of premature births in this pregnancy was 4.20%, and cesarean delivery accounted for 33.22%. Male newborns represented 52.97% of deliveries; 4.20% of newborns weighed < 2.5 kg, and 3.32% weighed > 4 kg (Table 1).

| Basic information | Number of people | Composition ratio (%) |

| Age (years) | ||

| 20-25 | 101 | 17.66 |

| 26-30 | 296 | 51.74 |

| 31-34 | 134 | 23.43 |

| ≥ 35 | 41 | 7.17 |

| Long term residence | ||

| Cities and towns | 299 | 52.27 |

| Rural district | 273 | 47.73 |

| Degree of education | ||

| Junior high school and below | 94 | 16.43 |

| High school or vocational school | 285 | 49.83 |

| College degree or above | 193 | 33.74 |

| Previous pregnancies | ||

| < 3 times | 349 | 61.01 |

| ≥ 3 times | 223 | 38.99 |

| Previous deliveries | ||

| < 2 times | 377 | 65.91 |

| ≥ 2 times | 195 | 34.09 |

| Is this pregnancy premature | ||

| Yes | 24 | 4.20 |

| No | 548 | 95.80 |

| Delivery method of this pregnancy | ||

| Vaginal birth | 382 | 66.78 |

| Caesarean birth | 190 | 33.22 |

| Gender of newborn | ||

| Male baby | 303 | 52.97 |

| Female infant | 269 | 47.03 |

| Neonatal weight | ||

| < 2.5 kg | 24 | 4.20 |

| 2.5-4 kg | 529 | 92.48 |

| > 4 kg | 19 | 3.32 |

GAD-7 scores revealed a dynamic pattern across pregnancy. The mean GAD-7 score in early pregnancy was 3.45 ± 0.41, with a detection rate of 6.99% (40 cases): Mild anxiety, 3.32% (19 cases); moderate, 2.45% (14 cases); severe, 1.22% (7 cases). In midpregnancy, the mean score increased to 4.83 ± 0.63, with a detection rate of 24.13% (138 cases): Mild anxiety, 13.64% (78 cases); moderate, 7.52% (43 cases); severe, 2.97% (17 cases). In late pregnancy, the mean score was 4.41 ± 0.55, with a detection rate of 16.96% (97 cases): Mild anxiety, 9.79% (56 cases); moderate, 5.24% (30 cases); severe, 1.92% (11 cases) (Table 2). Overall, anxiety showed a significant fluctuation trend - early pregnancy (low anxiety) to midpregnancy (increase) to late pregnancy (decline) - with χ2 = 21.092, P < 0.001.

| Stage | No anxiety | Mild anxiety | Moderate anxiety | Severe anxiety |

| Early pregnancy | 532 (93.01) | 19 (3.32) | 14 (2.45) | 7 (1.22) |

| Mid pregnancy | 434 (75.87) | 78 (13.64) | 43 (7.52) | 17 (2.97) |

| Late pregnancy | 475 (83.04) | 56 (9.79) | 30 (5.24) | 11 (1.92) |

PHQ-9 and EPDS scores indicated similar dynamic changes. In early pregnancy, the mean PHQ-9 score was 3.40 ± 0.35, with a detection rate of 5.42% (31 cases): Mild depression, 2.80% (16 cases); moderate, 1.75% (10 cases); severe, 0.87% (5 cases). In midpregnancy, the mean score increased to 4.95 ± 0.62, with a detection rate of 21.68% (124 cases): Mild, 12.76% (73 cases); moderate, 6.64% (38 cases); severe, 2.47% (13 cases). In late pregnancy, the mean score was 4.34 ± 0.49, with a detection rate of 13.81% (79 cases): Mild, 8.39% (48 cases); moderate, 4.02% (23 cases); severe, 1.40% (8 cases). At six weeks postpartum, the mean EPDS score was 8.63 ± 0.98, with a detection rate of 16.08% (92 cases): Mild, 9.62% (55 cases); moderate, 4.72% (27 cases); severe, 1.75% (10 cases) (Table 3). Depression followed the trend: Early pregnancy (low mood) to midpregnancy (increase) to late pregnancy (decline) to six weeks postpartum (rise again), showing significant difference across stages (χ2 = 13.619, P < 0.001).

| Stage | No depression | Mild depression | Moderate depression | Severe depression |

| Early pregnancy | 541 (94.58) | 16 (2.80) | 10 (1.75) | 5 (0.87) |

| Mid pregnancy | 448 (78.32) | 73 (12.76) | 38 (6.64) | 13 (2.47) |

| Late pregnancy | 493 (86.19) | 48 (8.39) | 23 (4.02) | 8 (1.40) |

| 6 weeks postpartum | 480 (83.91) | 55 (9.62) | 27 (4.72) | 10 (1.75) |

After controlling for baseline maternal variables - including age, residence, education level, gravidity and parity, preterm status, delivery mode, newborn sex, and birth weight - Pearson correlation analysis was used to assess relationships between anxiety and depression scores from pregnancy to six weeks postpartum. Results showed that anxiety and depression scores during early, mid, and late pregnancy were positively correlated (P < 0.001). From pregnancy to the postpartum period, anxiety and depression scores during pregnancy (early, mid, and late) correlated negatively with depression scores at six weeks postpartum (P < 0.001, Table 4).

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Early pregnancy anxiety score | 1.000 | ||||||

| Early pregnancy depression score | 0.6171 | 1.000 | |||||

| Mid pregnancy anxiety score | 0.7251 | 0.5421 | 1.000 | ||||

| Mid pregnancy depression score | 0.3451 | 0.4311 | 0.6081 | 1.000 | |||

| Late pregnancy anxiety score | 0.2741 | 0.4581 | 0.4911 | 0.5491 | 1.000 | ||

| Late pregnancy depression score | 0.3131 | 0.3521 | 0.3741 | 0.4831 | 0.5071 | 1.000 | |

| Postpartum depression score | -0.2751 | -0.4451 | -0.5431 | -0.5431 | -0.4761 | -0.4191 | 1.000 |

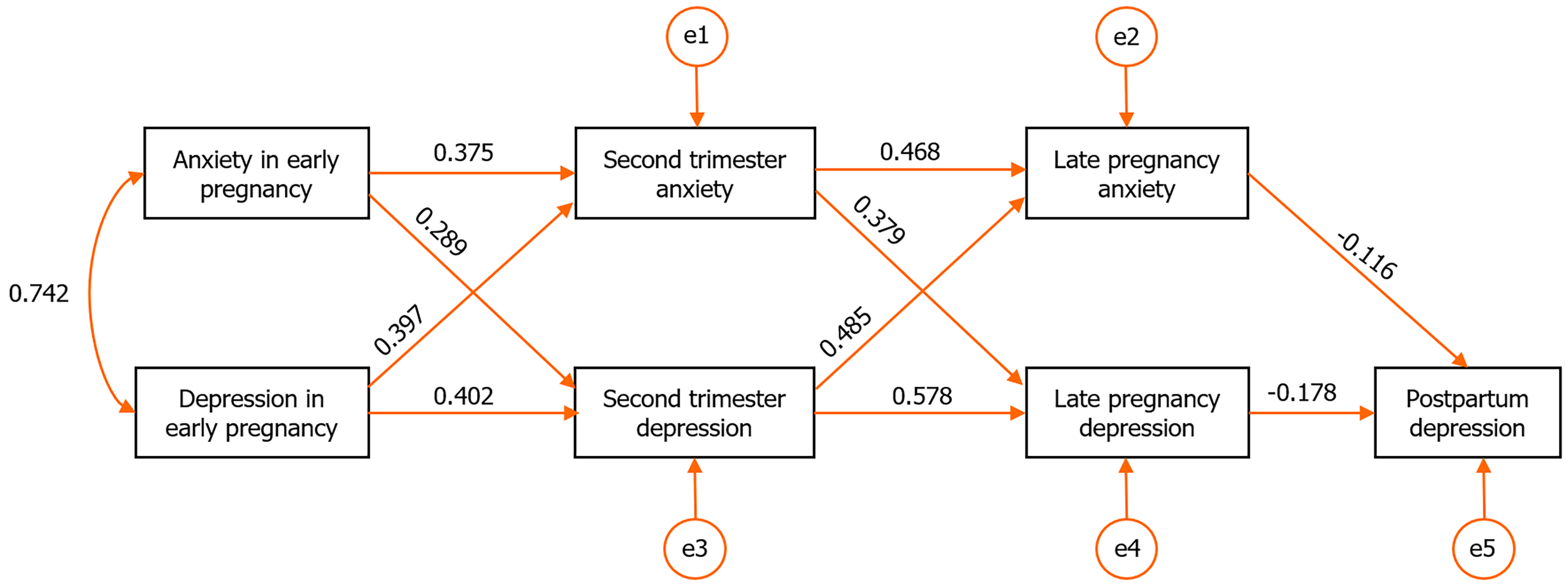

A cross-lagged model was constructed for anxiety and depression scores across pregnancy and up to six weeks postpartum. Using the maximum likelihood estimation method to test model fit, results show that the χ2 degree of freedom ratio of 2.761, the root mean square error of approximation of 0.012, the normalized fit index of 0.975 (> 0.900), and the comparative fit index of 0.965 (> 0.900), demonstrating good model adaptability. According to the model results, both anxiety and depression during pregnancy exerted significant time-lagged predictive effects on postpartum depression (P < 0.001, Figure 1).

As gestational age increases, physiological changes can lead to emotional fluctuations, including as irritability, anxiety, and low mood, in many pregnant women, thereby increasing the risk of postpartum depression[11,12]. Understanding the psychological changes from pregnancy to the postpartum period is therefore critical for effective prevention and intervention in postpartum depression.

In this study, the detection rates of anxiety among pregnant women in early, mid, and late pregnancy were 6.99%, 24.13% and 16.96% respectively. Anxiety levels followed a fluctuating trend - lowest in early pregnancy, peaking in midpregnancy, and declining in late pregnancy - differing from the findings of Shen et al[13]. We suggest that during early pregnancy (1-13 weeks), physical changes, including abdominal enlargement, skin pigmentation, and stretch marks, are minimal, and normal daily activity is largely maintained, resulting in relatively low anxiety. However, as gestation progresses, anxiety typically peaks during midpregnancy (14-27 weeks), consistent with Aziz et al[14], who also reported the highest of incidence of anxiety disorders at this stage. The likely reason is that noticeable abdominal protrusion, rapid weight gain, and emerging stretch marks alter body image perception and satisfaction, leading to heightened anxiety over appearance and loss of control. Moreover, the second trimester coincides with key prenatal clinical prenatal examinations - including Down syndrome screening, four-dimensional fetal ultrasound, and glucose tolerance testing - that increases psychological stress. Down syndrome screening, as the first chromosomal risk assessment, can cause intense concern if “high” or “borderline” risk results are reported. The four-dimensional ultrasound, assessing structural deformities such as cardiac or craniofacial defects, may heighten nervousness, while abnormal glucose tolerance results can lead to a diagnosis of “gestational diabetes,” imposing dietary restrictions, glucose monitoring, and lifestyle adjustments that raise self-health concerns. Collectively, these factors create a chronic stress environment during mid

This study’s results show that the detection rates of depression among pregnant women in early, mid, and late pregnancy, as well as at six weeks postpartum were 5.42%, 21.68%, 13.81%, and 16.08%, respectively. The overall trend fluctuated - lowest in early pregnancy, peaking in midpregnancy, declining in late pregnancy, and a rebound at six weeks postpartum - consistent with findings reported by Ahmed et al[16]. Normally, rising levels of human chorionic gonadotropin and progesterone during early pregnancy cause symptoms such as vomiting, nausea, fatigue, and breast tenderness, and the higher miscarriage risk in this period can heighten negative emotions[17]. However, the joy of early pregnancy often outweighs distress, and early B-ultrasound confirmation of fetal cardiac activity quickly alleviates miscarriage-related anxiety, preventing widespread depression. During midpregnancy, stress induced by fetal malformation screening, glucose tolerance testing, and health monitoring pressures can easily provoke anxiety and depression. Leung and Kaplan[18] also observed that midpregnancy is associated with higher rates of depression due to medical uncertainty, perceived life risks, limited family attention, hormonal fluctuations, and insufficient social support - aligning with this study’s finding of peak midpregnancy depression. The adaptive decline in depression during late pregnancy may stem from stabilization of fetal position, establishment of a delivery plan, and confirmation of normal fetal development, which reduce fear of the unknown. Increased family care, maternity leave, and emotional adjustment further ease psychological strain. The subsequent rebound at six weeks postpartum may result from physical exhaustion, such as newborns needing to be breastfed every 2-3 hours, accumulating sleep fragmentation to the physiological tolerance limit (especially nighttime care), leading to sleep deprivation[19]. Moreover, unmet expectations - including difficulties in breastfeeding or inability to soothe a crying infant - can shatter the “perfect mother” ideal, intensifying self-blame and depressive symptoms. Therefore, pregnant women should receive structured prenatal education early in gestation or by the start of the second trimester to prepare them for upcoming screenings and prevent emotional distress upon receiving a “high-risk” result. In addition, mandatory perinatal psychological screening windows should be established. During key prenatal visits (e.g., fetal malformation or glucose tolerance screenings), standardized anxiety and depression scales such as GAD-7 and PHQ-9 can be administered for rapid assessment. For those identified with anxiety or depression, interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (providing coping strategies for pregnancy-related stress) and relaxation training (encouraging calming exercises) should be implemented promptly to improve psychological well-being and reduce the risk of postpartum depression.

After controlling for baseline maternal data - age, residence, education level, gravidity and parity, prematurity, delivery mode, and newborn sex and weight - these findings remained robust. This study further found that anxiety and depression were positively correlated during early, mid, and late pregnancy, indicating high comorbidity and synchronous occurrence of these emotional disorders throughout gestation. This finding aligns with that of Liu et al[20], who reported that depression and anxiety often coexist during pregnancy. One explanation is that anxiety frequently precedes depression: Sustained anxiety and restlessness may erode psychological resilience, leading to emotional collapse and depressive symptoms. However, this study also revealed that anxiety and depression during pregnancy were negatively correlated with the risk of depression at six weeks postpartum. A likely reason lies in the different emphases of the screening tools used. The PHQ-9 scale, administered during pregnancy, focuses primarily on somatic symptoms, such as appetite and sleep disturbances, which are common in pregnancy - especially in the mid-to-late stages - and may not necessarily indicate depression, potentially inflating scores. In contrast, the EPDS emphasizes core emotional features such as anhedonia, anxiety, and self-blame. Thus, a pregnant woman might score high on the PHQ-9 due to pregnancy-related physical symptoms but lower on the EPDS postpartum once those symptoms subside. Furthermore, under persistent psychological stress during pregnancy, anxiety and depression may interact and mutually reinforce one another, amplifying negative emotions[21]. This cumulative process may unfold gradually, exerting a delayed influence on postpartum depression. A cross-lag analysis in this study confirmed a significant correlation between prenatal anxiety and depression and postpartum depressive symptoms, indicating that prenatal anxiety and depression have a time-lagged predictive effect on postpartum emotional states. This may occur because the detection of prenatal mental health issues during checkups prompt healthcare providers to deliver targeted psychological education and support[22]. Such interventions can enhance psychological resilience and self-efficacy in pregnant women, thereby alleviating or delaying postpartum depression[23]. The mechanism can be summarized as: Emergence of negative emotional signals during pregnancy to initiation of healthcare-based adaptive interventions (particularly psychological education) to strengthened psychological resilience and self-efficacy to prevention of rapid emotional decline postpartum.

This study has several limitations: (1) Conducted in Suzhou - a highly developed city with a large, well-educated population - the study sample was dominated by urban residents and women with at least a high school education. These factors are closely linked to better access to mental health knowledge and resources. Educated and urban women are generally more capable of understanding psychological changes during pregnancy and childbirth, recognizing early signs of depression or anxiety, and seek timely help to manage stress. Conversely, rural women have fewer opportunities for regular prenatal checkups or access to perinatal psychological services. This urban-rural disparity limits the generalizability of the findings to less educated or rural populations. Future studies should include multiple regions to improve external validity; and (2) The study utilized GAD-7 and PHQ-9 from prenatal handbooks, while postpartum depression was assessed with the EPDS. The inconsistency in measurement tools may introduce bias, as these scales emphasize different symptom domains. Future research should employ a unified instrument across pregnancy and postpartum stages to ensure comparability and confirm these findings.

In summary, anxiety during pregnancy exerts a time-lagged predictive effect on postpartum emotional states. Esta

| 1. | Pan D, Xu Y, Zhang L, Su Q, Chen M, Li B, Xiao Q, Gao Q, Peng X, Jiang B, Gu Y, Du Y, Gao P. Gene expression profile in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of postpartum depression patients. Sci Rep. 2018;8:10139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dennis CL, Falah-Hassani K, Shiri R. Prevalence of antenatal and postnatal anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:315-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 609] [Cited by in RCA: 950] [Article Influence: 105.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nisar A, Yin J, Waqas A, Bai X, Wang D, Rahman A, Li X. Prevalence of perinatal depression and its determinants in Mainland China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:1022-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 218] [Article Influence: 36.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li X, Gao R, Dai X, Liu H, Zhang J, Liu X, Si D, Deng T, Xia W. The association between symptoms of depression during pregnancy and low birth weight: a prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu Y, Wang Y, Wen S, Guo X, Xu L, Chen B, Chen P, Xu X, Wang Y. Association between social and family support and antenatal depression: a hospital-based study in Chengdu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lau Y, Fang L, Ho-Lim SST, Lim PI, Chi C, Wong SH, Cheng LJ. Cross-lagged models of health-related quality of life and breastfeeding across different body mass index groups: A three-wave prospective longitudinal study. Midwifery. 2022;112:103413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haga SM, Lisøy C, Drozd F, Valla L, Slinning K. A population-based study of the relationship between perinatal depressive symptoms and breastfeeding: a cross-lagged panel study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:235-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 20762] [Article Influence: 1038.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 31268] [Article Influence: 1250.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stefana A, Mirabella F, Gigantesco A, Camoni L; Perinatal Mental Health Nework; Perinatal Mental Health Nework also includes:. The screening accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) to detect perinatal depression with and without the self-harm item in pregnant and postpartum women. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2024;45:2404967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Duan KM, Ma JH, Wang SY, Huang Z, Zhou Y, Yu H. The role of tryptophan metabolism in postpartum depression. Metab Brain Dis. 2018;33:647-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Baumel A, Tinkelman A, Mathur N, Kane JM. Digital Peer-Support Platform (7Cups) as an Adjunct Treatment for Women With Postpartum Depression: Feasibility, Acceptability, and Preliminary Efficacy Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2018;6:e38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shen Q, Xiao M, Wang B, He T, Zhao J, Lei J. Comorbid Anxiety and Depression among Pregnant and Postpartum Women: A Longitudinal Population-Based Study. Depress Anxiety. 2024;2024:7802142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aziz HA, Yahya HDB, Ang WW, Lau Y. Global prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms in different trimesters of pregnancy: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Psychiatr Res. 2025;181:528-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van de Loo KFE, Vlenterie R, Nikkels SJ, Merkus PJFM, Roukema J, Verhaak CM, Roeleveld N, van Gelder MMHJ. Depression and anxiety during pregnancy: The influence of maternal characteristics. Birth. 2018;45:478-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ahmed A, Feng C, Bowen A, Muhajarine N. Latent trajectory groups of perinatal depressive and anxiety symptoms from pregnancy to early postpartum and their antenatal risk factors. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2018;21:689-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Werner E, Le HN, Babineau V, Grubb M. Preventive interventions for perinatal mood and anxiety disorders: A review of selected programs. Semin Perinatol. 2024;48:151944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Leung BM, Kaplan BJ. Perinatal depression: prevalence, risks, and the nutrition link--a review of the literature. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1566-1575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhao XH, Zhang ZH. Risk factors for postpartum depression: An evidence-based systematic review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu H, Huang F, Gao Y, Wang M, Lin Q, Kong Y, Zhou R, Zhang C, Chen Y. Network analysis of depression and anxiety symptoms and their associations with cognitive fusion among pregnant women. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rondung E, Massoudi P, Nieminen K, Wickberg B, Peira N, Silverstein R, Moberg K, Lundqvist M, Grundberg Å, Hultcrantz M. Identification of depression and anxiety during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of test accuracy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2024;103:423-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Min W, Jiang C, Li Z, Wang Z. The effect of mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy on postpartum mental health: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2023;331:452-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dol J, Richardson B, Murphy GT, Aston M, McMillan D, Campbell-Yeo M. Impact of mobile health interventions during the perinatal period on maternal psychosocial outcomes: a systematic review. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18:30-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/