Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113101

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: November 24, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 142 Days and 22.7 Hours

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a common mental illness that affects 10%-20% of women globally and has a major negative influence on the health of both the mother and the child. It is highly prevalent, although many cases go undetected. The etiology is multifactorial and involves biological, psychological, and social factors. This study aims to evaluate PPD incidence and identify related risk factors to provide evidence for clinical screening and prevention.

To evaluate PPD prevalence and associated risk variables.

This study included 376 women who delivered in University-Town Hospital of Chongqing Medical University and completed a 6-week post-partum follow-up. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was used to assess postpartum depressive symptoms, with a score ≥ 13 defined as post-partum depression.

The prevalence of PPD was 15.7% (59/376). Compared with the non-PPD group, the PPD group had significantly greater proportions of primiparas (71.2% vs 52.4%), unplanned pregnancies (33.9% vs 18.6%), and cesarean sections (54.2% vs 37.9%). The overall incidence of pregnancy complications, particularly gestational hypertension and diabetes, was significantly greater in the PPD group (47.5% vs 28.7%). Previous depression or anxiety history (27.1% vs 8.2%), lower marital satisfaction, and family dysfunction were more common in the PPD group. The Social Support Rating Scale total score was significantly lower in the PPD group than in the non-PD group (31.6 ± 7.2 vs 40.3 ± 8.1). The PPD group had sig

PPD was 15.7% common, and its pathophysiology included social, psychological, and biological factors. The biggest predictors were marital strife, prior mental illness, and a lack of social support. It is advised that high-risk moms be screened for pregnancy and that a thorough intervention system be put in place, which should include boosting social support, bolstering marital bonds, and improving psychological support.

Core Tip: This study investigated the prevalence, risk factors, and prenatal screening predictors of postpartum depression (PPD) in 376 women at 6 weeks post-partum. The prevalence of PPD according to the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) was 15.7%. Multivariate analysis revealed previous depression or anxiety, marital discord, insufficient social support, pregnancy complications, poor sleep quality, and economic pressure as key independent predictors. An EPDS score ≥ 9 in late pregnancy demonstrated good predictive value. Early identification of high-risk mothers and targeted prenatal interventions may reduce the incidence of PPD and improve maternal-infant health outcomes.

- Citation: Yang XW, Jiang XL, Wu YL. Clinical investigation of postpartum depression risk factors and screening predictors. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 113101

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/113101.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113101

The main symptoms of postpartum depression (PPD), an affective disease that affects people throughout the puerperium period, include a persistently low mood, decreased interest and energy levels, irregular sleep patterns, feelings of guilt, and suicidal thoughts. This disease has become one of the major global public health priorities among prenatal mental health problems[1-3].

PPD affects between 10%-20% of people worldwide, while there are significant differences between countries and regions. About 10%-15% of new moms in wealthy countries suffer from PPD, compared to 20%-25% in poor countries. This difference can be attributed to sociocultural factors and restricted access to healthcare. In China, the prevalence has been rising in tandem with the country's fast economic development, changing family dynamics, and growing demands on women's roles; recent studies have found prevalence rates between 11.8% and 18.5%. Additionally, data suggests that almost half of all PPD instances go undiagnosed or mistreated in clinical settings, resulting in many moms suffering for an extended period of time without the proper support[4-6].

Beyond the physical and mental health of the mother, PPD has a significant negative impact on family relations and the developmental paths of infants. Research has shown that PPD can lead to strained family connections, difficulties nursing, abnormal newborn temperament patterns, and disturbed mother-infant bonding. In severe cases, this illness may endanger the welfare of the unborn child and cause the mother to engage in self-harming behaviors or attempt suicide. According to longitudinal studies, children of postpartum depressed moms exhibit varying degrees of developmental delays in the social, emotional, linguistic, and cognitive domains; these effects may persist throughout childhood and adolescence[7-9].

PPD is a complex etiology that seems to be influenced by a combination of biological, psychological, and societal variables. From a biological perspective, postpartum mood disorders are largely triggered by the large postpartum changes in hormone levels, especially those related to oxytocin, progesterone, and estrogen. Other factors that may contribute to the development of PPD include changes in immunological and neuroendocrine system processes. From a psychosocial perspective, factors like past depressive episodes, personality traits that are prone to anxiety, psychological distress during pregnancy, marital disputes, a lack of family support networks, financial strain, and unfavorable life circumstances have all been shown to have a significant correlation with the occurrence of PPD[10-12].

Similar to this, obstetric factors have a major role in the development of PPD. PPD risk factors include high-risk pregnancies, issues during pregnancy (such as gestational hypertension and diabetes), difficult deliveries, cesarean sections, prolonged labor, and delivery problems. Inadequate postpartum pain management, difficulties nursing, and issues with the health of the newborn might also act as triggers. The number of advanced maternal-age pregnancies has increased recently as a result of the two-child and three-child policies, and this group may be at higher risk for PPD due to unique physiological and psychosocial traits[13].

Early detection of at-risk groups and timely management are essential tactics for reducing the negative effects of PPD. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), which has a comparatively high sensitivity and specificity, is currently a commonly used screening tool for PPD. However, real clinical screening rates are still below ideal and are hampered by limited medical resources, low PPD awareness among medical professionals, and stigma associated with mental health issues among mothers. Despite the National Health Commission's inclusion of PPD screening in postpartum care protocols in China, there is significant variation in its implementation across primary healthcare facilities, with notable differences between urban and rural settings. As a result, many PPD patients in China receive delayed or ignored dia

Pharmacological medicines, psychological therapy, and social support systems are all part of PPD treatment plans. The main pharmaceutical treatment for PPD at the moment is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, albeit breastfeeding safety issues need to be taken into account. Positive results have been seen using supportive psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and interpersonal therapy. Additionally, postpartum home visiting programs, peer support groups, and family support are crucial social support strategies for preventing and lessening the symptoms of PPD. However, precise identification of high-risk populations is necessary for the successful implementation of these treatments[15].

There are currently few thorough assessments of PPD, and the majority of domestic research on its frequency and risk factors focuses on single-variable analyses or geographic regions. At the same time, risk factors for PPD may dynamically change as social contexts and health situations change. Therefore, it is crucial to carry out current research on the incidence of PPD and multifaceted risk factors at our hospital in order to improve postpartum mental health services and inform clinical practice[16].

This study aims to retrospectively analyze clinical data from mothers who gave birth at our hospital's obstetric department between January 2020 and June 2024 in order to assess the prevalence of PPD and look into its risk factors from a biological, psychological, and sociological perspective. In order to reduce the prevalence of PPD and improve the health outcomes for mothers and infants, this study offers scientific support for the creation of efficient PPD screening methods and early intervention strategies.

Clinical data from moms who gave birth at our hospital's obstetric department and who finished 6-week postpartum follow-up evaluations between January 2020 and June 2024 were gathered for this study using a retrospective case-control research methodology. All participating mothers signed an informed consent form, and the study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (Approval No. IIT 2025-095). Maternal age ≥ 18 years; singleton pregnancies delivered at our hospital's obstetric department; grasp and completion of the EPDS evaluation; completion of follow-up assessment within the 6-week post-partum window; and thorough clinical documentation were the inclusion criteria. Previous severe mental illnesses like schizophrenia or bipolar disorder; prenatal depression diagnosed with ongoing postpartum medication; severe physical conditions during pregnancy or after delivery (like thyroid disorders or other endocrine conditions that may affect mood); infant mortality or severe illness requiring hospitalization within the first 28 days after delivery; multiple gestations; and incomplete clinical records were among the exclusion criteria. Based on research showing that PPD is 15% common in China, a minimum sample size of 346 cases was needed, with a two-sided α = 0.05 and a statistical power of 0.9. In the end, 376 moms were enrolled after taking probable data attrition into account. Six weeks after giving birth, all research participants had their EPDS evaluated. An EPDS score of > 13 was determined to be indicative of possible PPD symptoms based on worldwide standards and Chinese validation studies. Consequently, mothers were divided into two groups: Those with PPD (EPDS score ≥ 13) and those without (EPDS score < 13).

The observation indicators include general information (demographic characteristics, such as age, ethnicity, educational attainment, occupation, and monthly household income); factors related to pregnancy and delivery, such as gravidity, parity, pregnancy planning status, gestational complications, delivery method, gestational age at delivery, labor duration, and intrapartum complications; factors related to newborns, such as sex, birth weight, the Apgar score, prematurity status, and the presence of congenital abnormalities; psychosocial factors, such as psychiatric history, family psychiatric history, marital status and satisfaction, family relationship quality, social support availability, prenatal psychological condition, and postpartum stressful events; postpartum sleep quality; and lifestyle and postpartum adjustments, such as breastfeeding approach, postpartum physical recovery status, postpartum rest conditions, and infant care challenges. The study used a number of assessment tools, such as the EPDS (which consists of 10 items with ratings ranging from 0 to 3, with a total score of 30 points; ≥ 13 indicates possible PPD symptoms); the Social Support Rating Scale (SSRS; which assesses objective support, subjective support, and support use among mothers); the Family APGAR Questionnaire (which assesses family functioning, including flexibility, partnership, growth, affection, and resolve); the Marital Quality Questionnaire (which assesses marital relationship satisfaction); and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI; which measures sleep quality, with total scores > 7 indicating poor sleep quality). PPD prevalence (percentage of mothers with EPDS scores ≥ 13 at 6 weeks postpartum) was the main outcome of the study, while independent risk factors for PPD (factors showing significant associations with PPD through multivariate analysis) and individual risk factor weights [each factor's contribution to PPD occurrence, represented as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs)] were secondary endpoints. The methods used to collect the data were telephone follow-up (for mothers who were unable to attend follow-up appointments), questionnaire administration (mothers completed pertinent scale assessments during prenatal clinic visits and at 6-week post-partum visits), and medical record review (independent reviewers looked through the electronic medical record system to extract relevant information). Strict quality control procedures were put in place to guarantee the integrity of the research.

SPSS 25.0 software was used for statistical calculations in this inquiry. The measurement results are shown as means ± SD, and variance analysis or t tests are used to compare groups. Count data are shown as n (%), and χ2 tests are used to compare groups. Variables showing P < 0.1 were added to the multivariate logistic regression model after univariate analysis was conducted to find possible risk factors. PPD independent risk factors were identified using multivariate logistic regression analysis, and ORs with 95%CIs were calculated. Every statistical test was two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 376 moms were involved in this study; 59 (15.7%) were in the group with PPD, and 317 (84.3%) were not. Regarding age, ethnicity, occupation, and educational attainment, no statistically significant differences between the groups were found (P > 0.05). The PPD group's mean age was 29.4 ± 4.7 years, while the non-PD groups was 30.1 ± 4.3 years. In the PPD group, 89.8% of individuals were Han, but in the non-PPD group, 92.1% were (P = 0.553). Both groups' proportions of people with a high school diploma or more were 79.7% and 83.6%, respectively (P = 0.460). In each group, the employment rates were 61.0% and 66.2% (P = 0.432). The two groups' respective urban household registration percentages were 75.4% and 71.2% (P = 0.503). In both groups, the proportion of only children was 53.0% and 57.6%, respectively (P = 0.510). In terms of marital status, the corresponding categories included 90.2% and 86.4% of married people in stable partnerships (P = 0.364). There are 11.9% and 9.8% of the groups, respectively, had religious belief representation measured (P = 0.628). Prior to hospitalization for delivery, each group had 10.3 ± 2.1 and 10.5 ± 1.9 prenatal visits (P = 0.462). The corresponding groups' body mass index indices were 26.2 ± 2.7 kg/m2 and 26.8 ± 2.9 kg/m2 (P = 0.113). Regarding living circumstances, 45.8% and 39.7% of the groups, respectively, lived with their parents or in-laws (P = 0.383). The corresponding groups' stable residence percentages were 95.9% and 93.2% (P = 0.354). However, compared to the non-PPD group, low-income households (monthly income < 5000 yuan) showed a significantly higher representation in the PPD group (23.7% vs 13.2%, P = 0.031; Table 1).

| Characteristics | PPD group (n = 59) | Non-PPD group (n = 317) | Statistics | P value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 29.4 ± 4.7 | 30.1 ± 4.3 | t = 1.120 | 0.264 |

| Ethnicity | χ2 = 0.351 | 0.553 | ||

| Han | 53 (89.8) | 292 (92.1) | ||

| Minority | 6 (10.2) | 25 (7.9) | ||

| Education level | χ2 = 0.545 | 0.46 | ||

| High school and above | 47 (79.7) | 265 (83.6) | ||

| Junior high school and below | 12 (20.3) | 52 (16.4) | ||

| Employment status | χ2 = 0.617 | 0.432 | ||

| Employed | 36 (61.0) | 210 (66.2) | ||

| Unemployed/housewife | 23 (39.0) | 107 (33.8) | ||

| Household registration | χ2 = 0.448 | 0.503 | ||

| Urban | 42 (71.2) | 239 (75.4) | ||

| Rural | 17 (28.8) | 78 (24.6) | ||

| Only child | χ2 = 0.434 | 0.51 | ||

| Yes | 34 (57.6) | 168 (53.0) | ||

| No | 25 (42.4) | 149 (47.0) | ||

| Marital status | χ2 = 0.825 | 0.364 | ||

| Married with stable relationship | 51 (86.4) | 286 (90.2) | ||

| Others1 | 8 (13.6) | 31 (9.8) | ||

| Religious belief | χ2 = 0.235 | 0.628 | ||

| Yes | 7 (11.9) | 31 (9.8) | ||

| No | 52 (88.1) | 286 (90.2) | ||

| Number of prenatal visits (times), mean ± SD | 10.3 ± 2.1 | 10.5 ± 1.9 | t = 0.736 | 0.462 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 26.8 ± 2.9 | 26.2 ± 2.7 | t = 1.589 | 0.113 |

| Living arrangement | χ2 = 0.762 | 0.383 | ||

| With parents/in-laws | 27 (45.8) | 126 (39.7) | ||

| Couple only | 32 (54.2) | 191 (60.3) | ||

| Stable residence | χ2 = 0.858 | 0.354 | ||

| Yes | 55 (93.2) | 304 (95.9) | ||

| No | 4 (6.8) | 13 (4.1) | ||

| Monthly family income (yuan) | χ2 = 4.640 | 0.031a | ||

| < 5000 | 14 (23.7) | 42 (13.2) | ||

| ≥ 5000 | 45 (76.3) | 275 (86.8) |

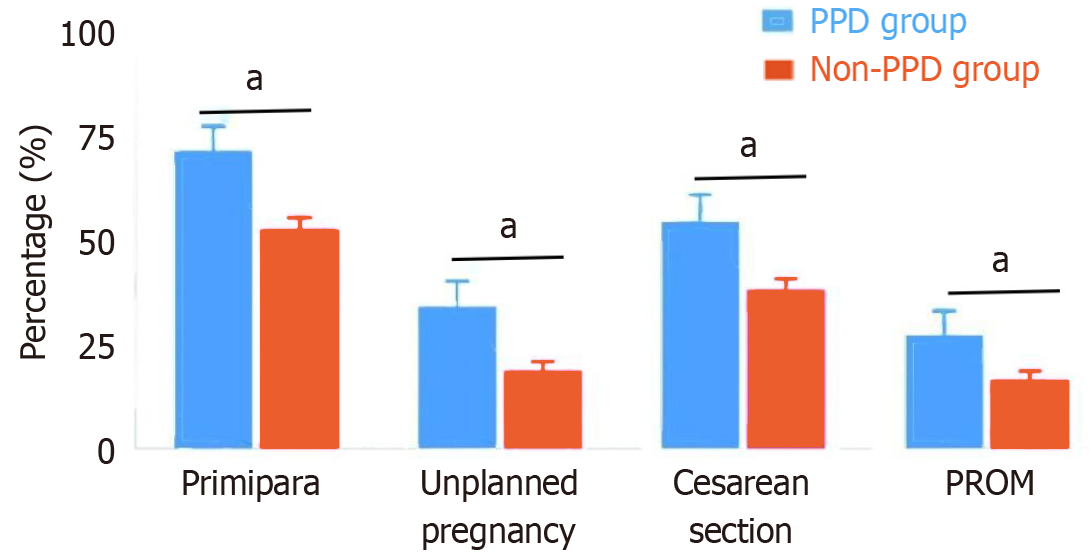

The proportion of primiparas in the PPD group was significantly greater than that in the non-PD group (71.2% vs 52.4%, P = 0.007). The proportion of unplanned pregnancies in the PPD group was also significantly greater (33.9% vs 18.6%, P = 0.008). The cesarean section rate in the PPD group was significantly greater than that in the non-PPD group (54.2% vs 37.9%, P = 0.019). The duration of labor in the PPD group was significantly longer than that in the non-PD group (13.8 ± 5.6 hours vs 11.2 ± 4.7 hours, P = 0.005). Additionally, the gestational weight gain in the PPD group was greater than that in the nonpregnant depression group (15.3 ± 3.8 kg vs 13.9 ± 3.5 kg, P = 0.011). The intrapartum blood loss in the PPD group was also significantly greater (312.5 ± 105.3 mL vs 278.6 ± 98.2 mL, P = 0.015). The postpartum hospital stay in the PPD group was longer than that in the nonpregnant depression group (4.5 ± 1.3 days vs 3.8 ± 1.1 days, P = 0.006). The incidence of premature rupture of membranes during delivery was also greater in the PPD group than in the non-PPD group (27.1% vs 16.4%, P = 0.047, Figure 1).

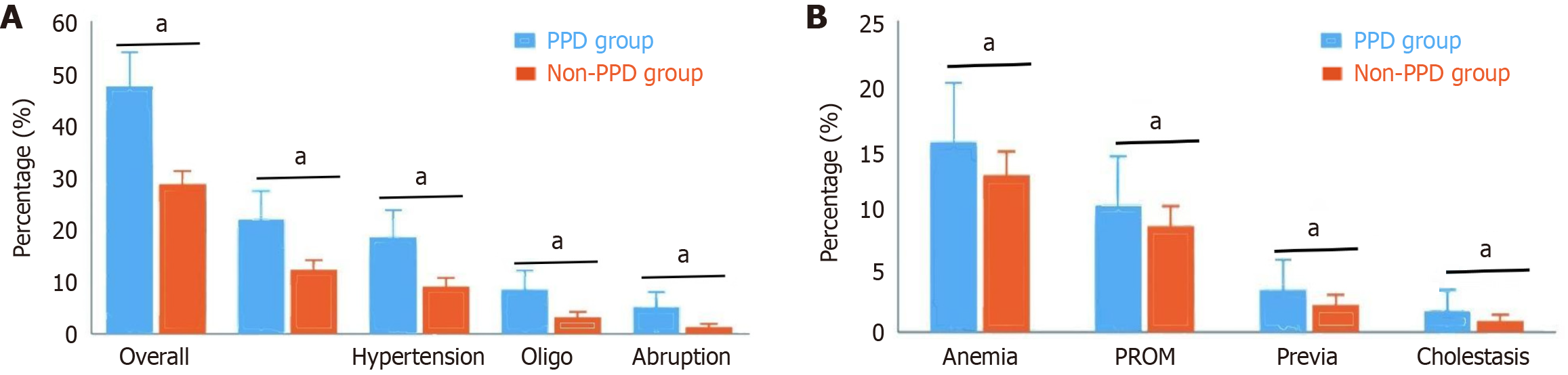

The overall incidence of pregnancy complications in the PPD group was significantly greater than that in the non-PPD group (47.5% vs 28.7%, P = 0.004). Analysis of specific complications revealed that the incidences of gestational hypertension (18.6% vs 9.1%, P = 0.027), gestational diabetes (22.0% vs 12.3%, P = 0.038), placental abruption (5.1% vs 1.3%, P = 0.042), and oligohydramnios (8.5% vs 3.2%, P = 0.049) were significantly greater in the PPD group than in the non-PPD group. Notably, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of gestational anemia (15.3% vs 12.6%, P = 0.572), premature rupture of membranes (10.2% vs 8.5%, P = 0.683), placenta previa (3.4% vs 2.2%, P = 0.585), or intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (1.7% vs 0.9%, P = 0.621). These results suggest that certain specific types of pregnancy complications, especially metabolic disorders and inadequate blood perfusion, may be closely associated with the occurrence of PPD (Figure 2).

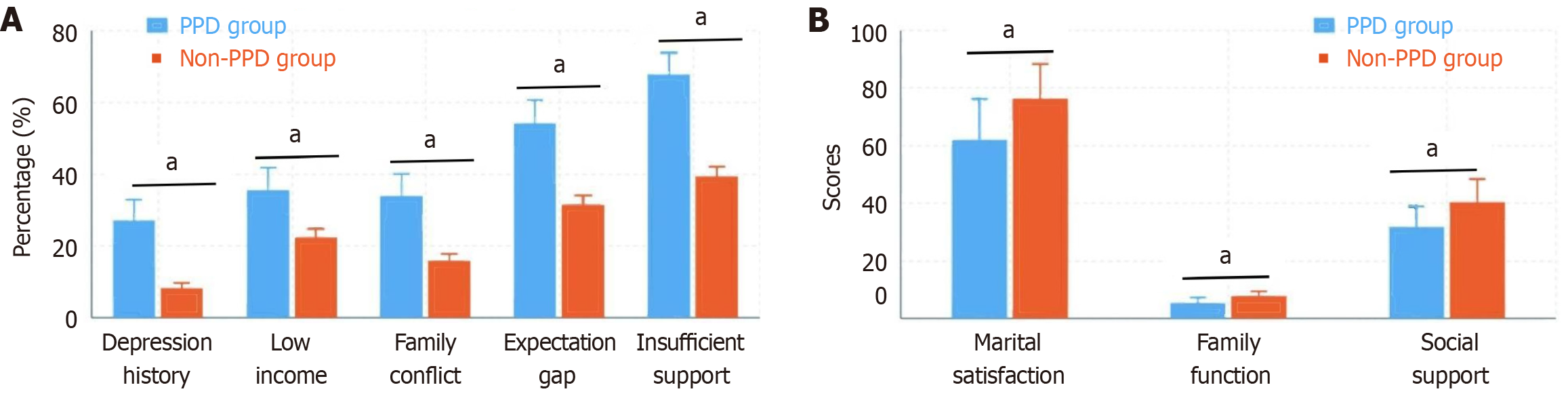

The proportion of those with a history of depression or anxiety was significantly greater in the PPD group than in the non-PPD group (27.1% vs 8.2%, P < 0.001). The marital satisfaction score in the PPD group was significantly lower than that in the nonpregnant depression group (62.1 ± 14.3 vs 76.5 ± 11.8, P < 0.001). The Family APGAR Questionnaire scores also indicated that the family function score in the PPD group was significantly lower than that in the non-PPD group (5.3 ± 1.9 vs 7.8 ± 1.6, P < 0.001). Additionally, the proportion of those with annual family income less than 50000 yuan was greater in the PPD group (35.6% vs 22.4%, P = 0.027), the incidence of family conflict was greater (33.9% vs 15.8%, P = 0.001), the proportion of those with discrepancies between prenatal expectations and postnatal reality was greater (54.2% vs 31.5%, P = 0.001), and the proportion of those with insufficient postpartum social support was greater (67.8% vs 39.4%, P < 0.001). The SSRS total score in the PPD group was significantly lower than that in the non-PPD group (31.6 ± 7.2 vs 40.3 ± 8.1, P < 0.001), with significantly lower scores in the dimensions of objective support, subjective support, and support utilization. Multivariate analysis revealed that a history of mental illness (OR = 4.26, 95%CI: 2.13-8.52), marital dissatisfaction (OR = 3.58, 95%CI: 1.79-7.14), and insufficient social support (OR = 3.12, 95%CI: 1.65-5.89) were independent risk factors for PPD (Figure 3).

The SSRS total score in the PPD group was significantly lower than that in the non-PPD group (31.6 ± 7.2 vs 40.3 ± 8.1, P < 0.001). Among the dimensions, objective support (9.4 ± 3.1 vs 12.6 ± 3.5, P < 0.001), subjective support (14.2 ± 4.3 vs 18.7 ± 4.5, P < 0.001), and support utilization (8.0 ± 2.1 vs 9.0 ± 2.3, P = 0.002) scores were significantly lower in the depression group than in the non-PPD group. Further analysis revealed that the proportion of those with insufficient spousal support in the PPD group was as high as 58.6%, which was significantly greater than the 31.9% reported in the non-PPD group (P < 0.001). The proportion of those with insufficient family support in the PPD group was 47.5%, which was higher than the 26.8% reported in the non-PD group (P = 0.002). The proportion of those with insufficient friend support in the PPD group was 42.4%, which was also higher than the 25.2% reported in the non-PD group (P = 0.007). The proportion of those who received professional healthcare follow-up within 1-month post-partum in the PPD group was 62.7%, which was lower than the 75.4% in the non-PD group (P = 0.038). Additionally, the satisfaction score with existing social support in the PPD group was significantly lower than that in the non-PPD group (5.8 ± 2.1 vs 7.4 ± 1.8, P < 0.001), and 67.8% of mothers in the PPD group indicated that social support could not meet their needs, whereas 38.5% of mothers in the non-PPD group did (P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis revealed that, after controlling for other variables, insufficient social support (OR = 3.12, 95%CI: 1.65-5.89) remained an independent risk factor for PPD (Table 2).

| Variables | PPD group (n = 59) | Non-PPD group (n = 317) | t/χ2 | P value |

| SSRS total score, mean ± SD | 31.6 ± 7.2 | 40.3 ± 8.1 | 7.935 | < 0.001c |

| SSRS dimensions, mean ± SD | ||||

| Objective support | 9.4 ± 3.1 | 12.6 ± 3.5 | 6.694 | < 0.001c |

| Subjective support | 14.2 ± 4.3 | 18.7 ± 4.5 | 7.158 | < 0.001c |

| Support utilization | 8.0 ± 2.1 | 9.0 ± 2.3 | 3.101 | 0.002b |

| Sources of insufficient support | ||||

| Spouse support | 34 (58.6) | 101 (31.9) | 14.966 | < 0.001c |

| Family member support | 28 (47.5) | 85 (26.8) | 9.997 | 0.002b |

| Friend support | 25 (42.4) | 80 (25.2) | 7.291 | 0.007b |

| Professional support | ||||

| Healthcare follow-up within 1 month | 37 (62.7) | 239 (75.4) | 4.301 | 0.038a |

| Satisfaction with support | ||||

| Satisfaction score, mean ± SD | 5.8 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 1.8 | 5.982 | < 0.001c |

| Unmet support needs | 40 (67.8) | 122 (38.5) | 17.381 | < 0.001c |

| Multivariate analysis result | ||||

| Insufficient social support, OR (95%CI) | 3.12 (1.65-5.89) | Reference | - | < 0.001c |

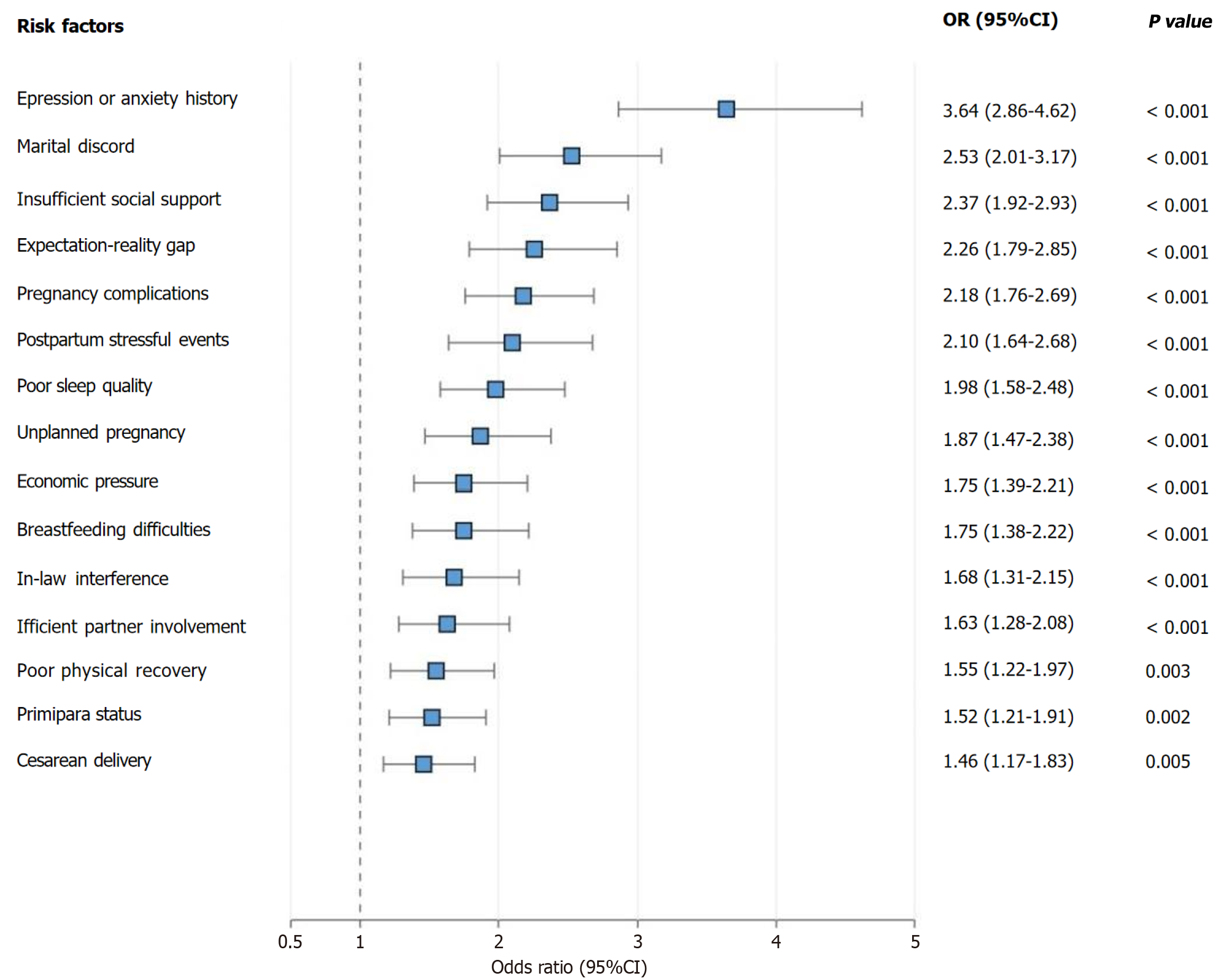

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that a history of depression or anxiety (OR = 3.64, 95%CI: 2.86-4.62, P < 0.001), marital discord (OR = 2.53, 95%CI: 2.01-3.17, P < 0.001), insufficient social support (OR = 2.37, 95%CI: 1.92-2.93, P < 0.001), pregnancy complications (OR = 2.18, 95%CI: 1.76-2.69, P < 0.001), poor postpartum sleep quality (OR = 1.98, 95%CI: 1.58-2.48, P < 0.001), economic pressure (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.39-2.21, P < 0.001), primipara status (OR = 1.52, 95%CI: 1.21-1.91, P = 0.002), and cesarean delivery (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 1.17-1.83, P = 0.005) were independent risk factors for PPD. Additionally, large discrepancies between prenatal expectations and postnatal reality (OR = 2.26, 95%CI: 1.79-2.85, P < 0.001), the occurrence of postpartum stressful events (OR = 2.10, 95%CI: 1.64-2.68, P < 0.001), unplanned pregnancy (OR = 1.87, 95%CI: 1.47-2.38, P < 0.001), postpartum breastfeeding difficulties (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.38-2.22, P < 0.001), parental or in-law interference in child-rearing methods (OR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.31-2.15, P < 0.001), insufficient spousal participation in child-rearing (OR = 1.63, 95%CI: 1.28-2.08, P < 0.001), and poor postpartum physical recovery (OR = 1.55, 95%CI: 1.22-1.97, P = 0.003) were also independent predictive factors for PPD. Subgroup analysis revealed that among primiparas, the risks of insufficient social support and poor postpartum sleep quality were more prominent (OR = 2.86, 95%CI: 2.18-3.74, P < 0.001 and OR = 2.43, 95%CI: 1.86-3.17, P < 0.001, respectively), whereas among multiparas, the risks of marital discord and economic pressure were relatively greater (OR = 3.12, 95%CI: 2.34-4.16, P < 0.001 and OR = 2.21, 95%CI: 1.65-2.97, P < 0.001, respectively; Figure 4).

The proportion of those experiencing major stressful events (such as serious illness or death of relatives, family conflicts, etc.) within 6 weeks post-partum was significantly greater in the PPD group than in the non-PPD group (30.5% vs 13.9%, P = 0.001). Among these, family conflict was the most common type of stressful event (18.6% in the PPD group vs 7.3% in the non-PPD group, P = 0.004). The PSQI scores revealed that sleep quality in the PPD group was significantly worse than that in the non-PPD group (11.5 ± 3.3 vs 8.2 ± 2.7, P < 0.001), and the proportion of those with PSQI scores > 7 (indicating poor sleep quality) in the PPD group was 81.4%, which was significantly greater than the 47.6% reported in the non-PPD group (P < 0.001). Further analysis revealed that difficulty falling asleep (68.5% in the PPD group vs 41.2% in the non-PPD group, P < 0.001), sleep maintenance problems (56.8% in the PPD group vs 33.4% in the non-PPD group, P = 0.002), and early morning awakening (45.8% in the PPD group vs 25.9% in the non-PPD group, P = 0.004) were the most common sleep problems in the PPD group. The reported rate of infant care difficulties (including frequent infant crying, feeding difficulties, etc.) in the PPD group was significantly greater than that in the non-PPD group (61.0% vs 38.5%, P = 0.001); difficulties in establishing breastfeeding (43.5% in the PPD group vs 26.7% in the non-PPD group, P = 0.008) and difficulties in establishing regular infant sleep patterns (54.2% in the PPD group vs 35.1% in the non-PPD group, P = 0.003) were especially prominent. Additionally, the proportion of poor maternal role adaptation was greater in the PPD group (47.5% vs 25.6%, P < 0.001), and the proportion of mothers with infant bonding difficulties was also greater (35.6% vs 18.3%, P = 0.003). However, there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in terms of newborn sex, birth weight, premature birth rate, or congenital anomaly incidence (all P > 0.05), suggesting that PPD may be more related to mothers’ subjective feelings and coping abilities than to objective newborn characteristics (Table 3).

| Variables | PPD group (n = 59) | Non-PPD group (n = 317) | Statistics | P value |

| Postpartum stressful events | ||||

| Any stressful event | 18 (30.5) | 44 (13.9) | χ2 = 10.73 | 0.001b |

| Family conflict | 11 (18.6) | 23 (7.3) | χ2 = 8.34 | 0.004b |

| Sleep quality | ||||

| PSQI score, mean ± SD | 11.5 ± 3.3 | 8.2 ± 2.7 | t = 8.45 | < 0.001a |

| Poor sleep quality (PSQI > 7) | 48 (81.4) | 151 (47.6) | χ2 = 22.78 | < 0.001a |

| Difficulty falling asleep | 40 (68.5) | 131 (41.2) | χ2 = 14.56 | < 0.001a |

| Sleep maintenance problems | 34 (56.8) | 106 (33.4) | χ2 = 9.87 | 0.002b |

| Early morning awakening | 27 (45.8) | 82 (25.9) | χ2 = 8.42 | 0.004b |

| Infant care difficulties | ||||

| Any infant care difficulty | 36 (61.0) | 122 (38.5) | χ2 = 10.96 | 0.001b |

| Breastfeeding difficulties | 26 (43.5) | 85 (26.7) | χ2 = 7.04 | 0.008b |

| Infant sleep regulation problems | 32 (54.2) | 111 (35.1) | χ2 = 8.64 | 0.003b |

| Maternal adaptation | ||||

| Poor maternal role adaptation | 28 (47.5) | 81 (25.6) | χ2 = 12.34 | < 0.001a |

| Mother-infant bonding difficulties | 21 (35.6) | 58 (18.3) | χ2 = 9.12 | 0.003b |

| Infant characteristics | ||||

| Male gender | 31 (52.5) | 164 (51.7) | χ2 = 0.01 | 0.915 |

| Birth weight (g), mean ± SD | 3214 ± 462 | 3278 ± 433 | χ2 = 1.03 | 0.305 |

| Preterm birth | 5 (8.5) | 21 (6.6) | χ2 = 0.27 | 0.602 |

| Congenital anomalies | 2 (3.4) | 7 (2.2) | Fisher's exact | 0.639 |

PPD, as one of the most common mental disorders during the postpartum period, not only seriously affects mothers’ physical and mental health but also may have long-term negative impacts on infant development and family functioning. Globally, the prevalence of PPD is approximately 10%-20%, although there are significant variations across different countries and regions[17-19]. The prevalence in developed countries is generally approximately 10%-15%, whereas in developing countries, it can reach 20%-25%. In China, with rapid economic development, changes in family structure, and the diversification of women's roles, the prevalence of PPD has shown an increasing trend, ranging from 11.8%-18.5%. More concerningly, approximately 50% of PPD cases are not clinically identified or are treated promptly, leaving many mothers in prolonged distress[20-23].

The etiology of PPD is complex and involves multiple factors, including biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors[24,25]. From a biological perspective, dramatic changes in postpartum hormone levels, especially fluctuations in estrogen, progesterone, and oxytocin, are considered important physiological foundations for postpartum mood disorders. Changes in the neuroendocrine and immune systems may also be involved in pathogenesis. From an obstetric perspective, factors such as high-risk pregnancy, pregnancy complications, cesarean section, and prolonged labor may increase the risk of PPD. From a psychosocial perspective, factors such as a previous history of mental illness, marital discord, inadequate family support, economic pressure, and negative life events have all been reported to be closely associated with PPD. Additionally, sleep disorders, breastfeeding difficulties, and infant care pressure may also become precipitating factors[26-29].

The EPDS, currently the most commonly used screening tool, has relatively high sensitivity and specificity and is widely applied in clinical practice and scientific research[30,31]. However, owing to limited medical resources, insuf

This study revealed that among the 376 mothers who delivered in our hospital's obstetric department, the prevalence of PPD at 6 weeks post-partum was 15.7%, which is consistent with the range reported in the domestic and international literature. This finding suggests that PPD remains a public health problem that cannot be ignored in our country and requires increased attention from the healthcare system. Through multivariate analysis, this study identified multiple independent risk factors for PPD, with the three strongest predictive factors being a previous history of depression or anxiety (OR = 3.64), marital discord (OR = 2.53), and insufficient social support (OR = 2.37), which is generally consistent with previous research findings, reemphasizing the core role of psychological and social support factors in the occurrence of PPD.

Notably, this study also revealed that pregnancy complications (OR = 2.18), especially gestational hypertension, diabetes, placental abruption, and oligohydramnios, which involve metabolic disorders and inadequate blood perfusion, were significantly associated with PPD. These findings suggest that pregnancy comorbidities may affect postpartum emotional states through both physiological and psychological pathways. Additionally, cesarean section (OR = 1.46) and primipara status (OR = 1.52) were also independent risk factors, possibly related to surgical trauma, postpartum recovery difficulties, and lack of childcare experience. There are a number of possible explanations for why these particular issues are more strongly linked to PPD than to other pregnant conditions: (1) Metabolic complications, like gestational diabetes, involve insulin resistance and inflammatory pathways that have been linked to mood disorders; (2) Placental complications and hypertensive disorders reflect inadequate uteroplacental perfusion, which may affect the neuroendocrine regulation of the mother; (3) These complications often require medical interventions and intensive monitoring, which increases the stress and anxiety of the mother; and (4) Women with these conditions may have a greater fear of the outcomes for both the mother and the fetus, which contributes to psychological distress that lasts after giving birth.

This study also revealed that poor postpartum sleep quality (OR = 1.98) was closely associated with PPD, with significantly higher PSQI scores in the PPD group than in the non-PPD group (11.5 ± 3.3 vs 8.2 ± 2.7). Sleep disorders may be an important warning signal for PPD and may also form a vicious cycle: Sleep deprivation leads to decreased emo

Several contextual factors can be linked to the similarities and discrepancies between our findings and those of foreign studies. In contrast to studies from collectivist Asian cultures, the prevalence of social support deficiency as a risk factor (OR = 2.37) is higher than in most Western studies. This could be due to China's particular cultural emphasis on extended family support during the postpartum phase as well as the difficulties caused by rapid urbanization and migration patterns that cut off young mothers from traditional support networks. Although our effect size is somewhat smaller, the association between cesarean section and PPD (OR = 1.46) is consistent with meta-analyses from Western nations. This could be due to variations in cesarean section procedures, pain management techniques, or cultural perspectives regarding various delivery methods. Contrary to some Western research, our findings that economic pressure has a greater impact on multiparas than primiparas are intriguing. This could be a result of China's recent two-child and three-child policies, which may make financial worries about raising multiple children in an increasingly costly urban setting especially pressing for families with children already.

Subgroup analysis revealed differences in risk factors between primiparas and multiparas: Primiparas were more susceptible to the influence of insufficient social support and poor sleep quality, whereas multiparas were more susceptible to the influence of marital discord and economic pressure. This result suggests that differentiated prevention and intervention strategies may need to be developed for populations with different parities.

This study also revealed that an EPDS score ≥ 9 in late pregnancy had moderate predictive value for PPD (AUC = 0.763), with a sensitivity of 76.3% and specificity of 65.9%. This result suggests that prenatal screening may help with early identification of high-risk mothers, providing a basis for prenatal intervention and close postpartum follow-up, thereby achieving primary prevention of PPD.

Important clinical ramifications for early detection and intervention result from this finding. Healthcare professionals may detect about 75% of women who will experience PPD while keeping a fair specificity to prevent over screening thanks to the threshold, which provides a useful balance between sensitivity and specificity. Using this criteria for prenatal screening could allow for more focused preventive measures during pregnancy, like closer postpartum monitoring for high-risk moms, cognitive behavioral therapy, or improved psychosocial support. However, for successful incorporation into clinical practice, a number of factors need to be taken into account. Initially, the moderate specificity (65.9%) indicates that almost one-third of women who test positive might not go on to have PPD, requiring appropriate counseling to prevent needless worry. Since thorough screening necessitates skilled staff, follow-up infrastructure, and intervention programs, resource allocation must be taken into account as well. Third, rather than being a stand-alone treatment, prenatal screening ought to be a component of a larger perinatal mental health approach. Future studies ought to assess the financial viability of prenatal screening initiatives and identify the best ways to assist women who test positive for the test in various medical environments.

Due to its multifaceted nature, PPD necessitates multifaceted preventative and intervention techniques. To enhance maternal and infant health outcomes, comprehensive screening and early intervention programs should be implemented for high-risk moms, such as those with a history of mental health issues, marital problems, a lack of social support, or pregnancy complications.

| 1. | Le J, Alhusen J, Dreisbach C. Screening for Partner Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2023;48:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alimi R, Azmoude E, Moradi M, Zamani M. The Association of Breastfeeding with a Reduced Risk of Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Breastfeed Med. 2022;17:290-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arifunhera J, Mirunalini R. An update on the pharmacotherapy of postpartum depression. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025;168:933-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Asare H, Rosi A, Scazzina F, Faber M, Smuts CM, Ricci C. Maternal postpartum depression in relation to child undernutrition in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:979-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beck CT. Experiences of Postpartum Depression in Women of Color. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2023;48:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Wu L, Zheng Y, Liu J, Luo R, Wu D, Xu P, Wu D, Li X. Comprehensive evaluation of the efficacy and safety of LPV/r drugs in the treatment of SARS and MERS to provide potential treatment options for COVID-19. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:10833-10852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cafiero PJ, Justich Zabala P. Postpartum depression: Impact on pregnant women and the postnatal physical, emotional, and cognitive development of their children. An ecological perspective. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2024;122:e202310217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dennis CL, Singla DR, Brown HK, Savel K, Clark CT, Grigoriadis S, Vigod SN. Postpartum Depression: A Clinical Review of Impact and Current Treatment Solutions. Drugs. 2024;84:645-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dessì A, Pianese G, Mureddu P, Fanos V, Bosco A. From Breastfeeding to Support in Mothers' Feeding Choices: A Key Role in the Prevention of Postpartum Depression? Nutrients. 2024;16:2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Flor-Alemany M, Migueles JH, Alemany-Arrebola I, Aparicio VA, Baena-García L. Exercise, Mediterranean Diet Adherence or Both during Pregnancy to Prevent Postpartum Depression-GESTAFIT Trial Secondary Analyses. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Frankel LA, Sampige R, Pfeffer K, Zopatti KL. Depression During the Postpartum Period and Impacts on Parent-Child Relationships: A Narrative Review. J Genet Psychol. 2024;185:146-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Garcia V, Meyer E, Witkop C. Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression in Active Duty Women. Mil Med. 2022;187:e562-e566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gopalan P, Spada ML, Shenai N, Brockman I, Keil M, Livingston S, Moses-Kolko E, Nichols N, O'Toole K, Quinn B, Glance JB. Postpartum Depression-Identifying Risk and Access to Intervention. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2022;24:889-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hawkins SS. Screening and the New Treatment for Postpartum Depression. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2023;52:429-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wu L, Zhong Y, Wu D, Xu P, Ruan X, Yan J, Liu J, Li X. Immunomodulatory Factor TIM3 of Cytolytic Active Genes Affected the Survival and Prognosis of Lung Adenocarcinoma Patients by Multi-Omics Analysis. Biomedicines. 2022;10:2248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lewkowitz AK, Whelan AR, Ayala NK, Hardi A, Stoll C, Battle CL, Tuuli MG, Ranney ML, Miller ES. The effect of digital health interventions on postpartum depression or anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2024;230:12-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stewart AL, Payne JL. Perinatal Depression: A Review and an Update. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46:447-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wu L, Liu Q, Ruan X, Luan X, Zhong Y, Liu J, Yan J, Li X. Multiple Omics Analysis of the Role of RBM10 Gene Instability in Immune Regulation and Drug Sensitivity in Patients with Lung Adenocarcinoma (LUAD). Biomedicines. 2023;11:1861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Valverde N, Mollejo E, Legarra L, Gómez-Gutiérrez M. Psychodynamic Psychotherapy for Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review. Matern Child Health J. 2023;27:1156-1164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu QR, Zong QK, Ding LL, Dai HY, Sun Y, Dong YY, Ren ZY, Hashimoto K, Yang JJ. Effects of perioperative use of esketamine on postpartum depression risk in patients undergoing cesarean section: A randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:815-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Liu X, Wang S, Wang G. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Postpartum Depression in Women: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:2665-2677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 283] [Article Influence: 70.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Luo F, Zhu Z, Du Y, Chen L, Cheng Y. Risk Factors for Postpartum Depression Based on Genetic and Epigenetic Interactions. Mol Neurobiol. 2023;60:3979-4003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu L, Zheng Y, Ruan X, Wu D, Xu P, Liu J, Wu D, Li X. Long-chain noncoding ribonucleic acids affect the survival and prognosis of patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma through the autophagy pathway: construction of a prognostic model. Drugs. 2022;33:e590-e603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wells T. Postpartum Depression: Screening and Collaborative Management. Prim Care. 2023;50:127-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Worthen RJ, Beurel E. Inflammatory and neurodegenerative pathophysiology implicated in postpartum depression. Neurobiol Dis. 2022;165:105646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Newman DM, Boyarsky M, Mayo D. Postpartum depression. JAAPA. 2022;35:54-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nguyen HTH, Hoang PA, Do TKL, Taylor-Robinson AW, Nguyen TTH. Postpartum depression in Vietnam: a scoping review of symptoms, consequences, and management. BMC Womens Health. 2023;23:391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wu L, Zhong Y, Yu X, Wu D, Xu P, Lv L, Ruan X, Liu Q, Feng Y, Liu J, Li X. Selective poly adenylation predicts the efficacy of immunotherapy in patients with lung adenocarcinoma by multiple omics research. Anticancer Drugs. 2022;33:943-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Park SH, Kim JI. Predictive validity of the Edinburgh postnatal depression scale and other tools for screening depression in pregnant and postpartum women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2023;307:1331-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yu M, Washburn M, Bayhi JL, Xu W, Carr L, Sampson M. Home visiting for postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2025;1:CD015984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zacher Kjeldsen MM, Bricca A, Liu X, Frokjaer VG, Madsen KB, Munk-Olsen T. Family History of Psychiatric Disorders as a Risk Factor for Maternal Postpartum Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2022;79:1004-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Patatanian E, Nguyen DR. Brexanolone: A Novel Drug for the Treatment of Postpartum Depression. J Pharm Pract. 2022;35:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Qin X, Liu C, Zhu W, Chen Y, Wang Y. Preventing Postpartum Depression in the Early Postpartum Period Using an App-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Program: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:16824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pandey AN, Yadav PK, Premkumar KV, Pandey AK, Chaube SK. Therapeutic Potential of Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) for Psychological Stress-mediated Women's Reproductive Health Disorders. Innov Discov. 2025;2:11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Sharma P, Kalra S, Singh Balhara YP. Postpartum Depression and Diabetes. J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72:177-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sharma V, Sharkey KM, Palagini L, Mazmanian D, Thomson M. Preventing recurrence of postpartum depression by regulating sleep. Expert Rev Neurother. 2023;23:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/