Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112819

Revised: September 25, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 156 Days and 22.8 Hours

Preoperative sleep disorders are common in elderly gastric cancer patients and may increase the risk of postoperative anxiety and depression. Traditional anes

To determine whether EEG-guided anesthesia improves psychological recovery by stabilizing anesthesia depth in elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders.

This retrospective study included 240 patients aged ≥ 65 years with preoperative sleep disorders (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index ≥ 5) who underwent elective radi

A total of 240 elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders were included (118 EEG group, 122 control group) with well-matched baseline characteristics. EEG-guided anesthesia significantly reduced anesthetic drug consumption (propofol: 5.8 ± 1.2 mg/kg/hour vs 7.3 ± 1.4 mg/kg/hour, P < 0.001; remifentanil: 0.18 ± 0.04 μg/kg/minute vs 0.24 ± 0.05 μg/kg/minute, P < 0.001) and achieved 18.6% cost reduction. Primary outcomes showed the EEG group had significantly lower postoperative anxiety and depression scores at 3 days (HADS total: 11.8 ± 3.7 vs 15.9 ± 4.9, P < 0.001) and 1 month (8.7 ± 3.2 vs 13.2 ± 4.1, P < 0.001). The proportion of patients with clinically significant symptoms was reduced from 62.3% to 39.0% at 3 days and from 45.9% to 21.2% at 1 month (both P < 0.001). Multivariate analysis identified EEG-guided anesthesia as the strongest protective factor [odds ratio (OR) = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.41-0.78, P = 0.003], while poor sleep efficiency (OR = 2.24, P < 0.001) and frequent sleep disturbances (OR = 1.95, P = 0.001) were the most significant risk factors. Subgroup analysis revealed a dose-response relationship, with greatest benefits in patients with severe sleep disorders. BIS stability metrics strongly correlated with psychological outcomes (r = -0.462 for target range maintenance, P < 0.001). Secondary outcomes demonstrated significant improvements in the EEG group: (1) Lower complication rates (32.2% vs 48.4%, P = 0.010); (2) Reduced postoperative delirium (8.5% vs 17.2%, P = 0.038); and (3) Superior pain control, faster recovery, and shorter hospital stay (10.8 ± 2.7 days vs 12.5 ± 3.0 days, P < 0.001).

For elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders, individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring significantly reduces postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms, lowers postoperative delirium risk, shortens hospital stay, and improves postoperative quality of life. The stability of anesthesia depth is closely associated with postoperative mental health outcomes, providing new clinical evidence and individualized stra

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that electroencephalogram (EEG)-guided anesthesia significantly reduces postoperative anxiety and depression in elderly gastric cancer patients with sleep disorders, with greatest benefits in severe cases. Anesthesia depth stability, rather than absolute values, critically influences mental health outcomes. EEG monitoring also reduces drug costs by 18.6% and complications, supporting routine Bispectral Index implementation in this vulnerable population.

- Citation: Zhang XM, Yuan L, Chen YL, Shuai SC, Ye XM, Zhao JB. Electroencephalogram-guided anesthesia and postoperative anxiety and depression in elderly gastric cancer patients with sleep disorders. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 112819

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/112819.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112819

Gastric cancer is one of the most prevalent malignant tumors globally, with particularly high incidence and mortality rates in Asian countries. In China, gastric cancer incidence shows a clear age-related pattern, with significantly higher rates in populations over 65 years compared to younger groups. With the accelerating aging population, the number of elderly gastric cancer patients continues to increase, presenting enormous challenges for clinical diagnosis, treatment, and perioperative management[1-4].

Elderly gastric cancer patients often present with multiple comorbidities, with sleep disorders being particularly common. Research indicates that approximately 60%-75% of elderly gastric cancer patients experience various sleep problems, including difficulty falling asleep, sleep interruptions, early awakening, and decreased sleep quality. These sleep disorders primarily stem from cancer-related pain, metabolic disturbances caused by the tumor itself, psychological stress, and medication side effects. Notably, sleep disorders not only reduce patients' quality of life but may also negatively impact perioperative management and prognosis[5-7].

Radical gastrectomy is one of the primary treatment methods for elderly gastric cancer patients; however, surgical stress responses can lead to various postoperative complications, including neuropsychiatric symptoms such as anxiety and depression. Compared to younger patients, elderly patients show higher sensitivity to anesthetic drugs, decreased drug metabolism and clearance abilities, making them more susceptible to fluctuations in anesthesia depth and related adverse events. Clinical research indicates that elderly patients with preoperative sleep disorders have significantly higher rates of postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms compared to age-matched patients with normal sleep, demonstrating a clear correlation between these factors. A prospective study involving 186 elderly gastric cancer patients found that for each 1-point increase in preoperative Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score, the risk of postoperative anxiety and depression increased by approximately 12%. This may be related to pathophysiological changes caused by long-term sleep disorders, including neurotransmitter imbalances, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, and elevated inflammatory factor levels[8,9].

Traditional anesthesia depth monitoring primarily relies on clinical observation and conventional vital signs (such as heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, etc.), which often lag behind actual changes in the central nervous system and have limited sensitivity and specificity in elderly patients. Research shows that anesthesia management based on conventional indicators may lead to inappropriate anesthesia depth in approximately 40% of elderly patients, including anesthesia that is either too deep or too shallow. Excessively deep anesthesia increases the risk of intraoperative hypo

Electroencephalogram (EEG) monitoring technology, particularly Bispectral Index (BIS) monitoring, provides objective indicators for evaluating anesthesia depth through real-time analysis of EEG signals. BIS values range from 0 to 100, with 40-60 considered the ideal range for general anesthesia. Compared to traditional monitoring, EEG monitoring can more directly and promptly reflect the functional state of the central nervous system, providing an objective basis for individualized adjustment of anesthetic drugs. Recent research suggests that anesthesia management guided by EEG monitoring can reduce the risk of intraoperative awareness, decrease anesthetic drug usage, accelerate postoperative recovery, and potentially improve cognitive function outcomes. However, the impact of EEG monitoring on postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms in elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders has not been thoroughly studied[12,13].

There is a close connection between sleep disorders and EEG activity. Research shows that patients with chronic sleep disorders often exhibit enhanced alpha and beta wave activity and weakened delta and theta wave activity in their EEGs, reflecting abnormal cerebral cortical function. These abnormalities may affect patients' sensitivity and responsiveness to anesthetic drugs, causing standard doses of anesthetics to produce different depths of anesthesia in different patients. Therefore, for elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders, individualized anesthesia plans guided by EEG monitoring may provide more precise control of anesthesia depth compared to traditional methods, thereby reducing perioperative risks and improving postoperative neuropsychiatric function[14].

Additionally, growing evidence suggests that appropriate anesthesia depth not only affects intraoperative stability but may also influence postoperative recovery and long-term prognosis through various mechanisms, including regulation of neuroendocrine responses, inflammatory processes, and immune function. These effects may be particularly important for elderly gastric cancer patients, who often have decreased multiple organ function reserves and chronic disease burdens[15].

Despite the theoretical and preliminary evidence supporting the potential value of EEG monitoring in anesthesia management for elderly gastric cancer patients, systematic research on its impact on postoperative anxiety and de

This study retrospectively included 240 patients who underwent elective radical gastrectomy in our hospital's Gastrointestinal Surgery Department between January 2022 and December 2023.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 65 years; (2) Clinical and pathological diagnosis of gastric cancer (TNM stages I-III); (3) Undergoing elective radical gastrectomy (including proximal subtotal gastrectomy, distal subtotal gastrectomy, or total gastrectomy); (4) Preoperative PSQI score ≥ 5 points, indicating sleep disorders, assessed prospectively during preoperative clinic visits typically 1 week and 2 weeks before surgery as part of routine clinical care; (5) Preoperative PSQI score ≥ 5 points, indicating sleep disorders; (6) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification grade II-III; and (7) Complete clinical data, including preoperative sleep assessments, intraoperative anesthesia records, and postoperative follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Emergency surgery; (2) Preoperative diagnosis of mental illness or current use of psychiatric medications; (3) Preoperative cognitive impairment (Mini-Mental State Examination < 24 points); (4) Preoperative use of sedative-hypnotic medications for > 4 weeks; (5) Chemotherapy or radiotherapy within 3 months before surgery; (6) Intraoperative finding of unresectable tumor or palliative surgery only; (7) Death within 30 days after surgery or transfer to intensive care unit for > 48 hours due to severe complications; and (8) Language communication barriers or inability to complete questionnaire assessments.

All patients underwent surgery performed by the same surgical team using similar surgical approaches and extents. Patients were divided into two groups based on anesthesia monitoring method: (1) The EEG monitoring group (EEG group, n = 118) used intraoperative BIS monitoring (BIS Vista monitor, Medtronic, United States) throughout the procedure, with anesthetic drug dosage adjusted according to BIS values (target maintenance between 40 and 60); and (2) The conventional monitoring group (control group, n = 122) relied only on conventional clinical indicators (such as heart rate, blood pressure, pupil size, respiratory parameters, etc.) to adjust anesthesia depth.

Both groups employed similar anesthesia protocols, including anesthesia induction (midazolam 0.02-0.04 mg/kg, sufentanil 0.3-0.5 μg/kg, propofol 1.5-2.5 mg/kg, cisatracurium 0.15-0.2 mg/kg) and anesthesia maintenance (sevoflurane or target-controlled infusion of propofol, continuous pump infusion of remifentanil 0.1-0.3 μg/kg/minute, with intermittent cisatracurium to maintain muscle relaxation as needed). The difference between the two groups was: (1) The EEG group adjusted anesthetic drug dosage according to BIS values, maintaining BIS values between 40 and 60; and (2) The control group adjusted anesthetic drug dosage based on conventional clinical signs and the anesthesiologist's experience. In both groups, sevoflurane or propofol was discontinued 30 minutes before the end of surgery, intravenous tramadol 100 mg was administered to prevent postoperative pain, and neostigmine and atropine were used to antagonize residual muscle relaxation at the end of surgery.

General data collected in this study included demographic characteristics [age, gender, body mass index (BMI)], baseline clinical characteristics (ASA classification, comorbidities, preoperative hemoglobin and albumin levels), tumor-related characteristics (TNM staging, tumor location, differentiation degree), preoperative assessments [PSQI with individual component analysis including sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores], and surgery-related indicators (surgical approach, operation time, intraoperative blood loss, blood transfusion). Anesthesia-related indicators included total anesthetic drug usage (propofol/sevoflurane, opioids, muscle relaxants), anesthesia duration, BIS value fluctuations in the EEG group (maximum value, minimum value, average value, standard deviation), intraoperative hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 65 mmHg) and bradycardia (heart rate < 50 beats/minute) occurrence frequency and duration, and intraoperative use of vasopressors and atropine. The primary endpoints were HADS scores at 3 days and 1 month postoperatively during follow-up, including the anxiety subscale (HADS-A, 0-21 points) and depression subscale (HADS-D, 0-21 points), with a HADS total score ≥ 8 considered indicative of significant anxiety or depression symptoms. Secondary endpoints included postoperative delirium incidence (assessed using the Confusion Assessment Method, evaluated twice daily for 3 consecutive days after surgery), postoperative pain level [assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) recording pain scores at rest and during activity on postoperative days 1, 2, and 3], postoperative nausea and vomiting incidence, time to first bowel sounds and first flatus, length of hospital stay, 30-day postoperative complication rate, and 30-day postoperative quality of life score (assessed using the health-related quality of life scale Short-Form 36).

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 25.0 software was used for statistical analysis. Measurement data were expressed as mean ± SD, and between-group comparisons were performed using independent sample t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests; count data were expressed as n (%), and between-group comparisons were performed using χ2 tests or Fisher's exact probability method. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine relationships between individual PSQI components and postoperative outcomes. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors affecting postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms. For missing data, multiple imputation was used if the missing rate was < 5%; if the missing rate was > 5%, the case was excluded. All tests were two-sided, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

A total of 240 patients were included in this study, with 118 in the EEG group and 122 in the control group. The mean ages of the two groups were 72.3 ± 5.7 years and 71.8 ± 6.1 years, respectively; male percentages were 63.6% (75/118) and 64.8% (79/122); mean BMI was 23.5 ± 2.8 kg/m² and 23.2 ± 3.0 kg/m²; ASA classification (grade II/III) distribution was 72/46 cases and 69/53 cases; rates of comorbid hypertension, diabetes, and coronary heart disease were 46.6% (55/118) vs 48.4% (59/122), 30.5% (36/118) vs 32.8% (40/122), and 22.0% (26/118) vs 24.6% (30/122), respectively; TNM staging (stage I/II/III) distribution was 32/51/35 and 30/53/39 cases; tumor location (cardia/body/antrum) distribution was 28/45/45 cases and 31/43/48 cases; differentiation degree (well/moderately/poorly differentiated) distribution was 21/62/35 cases and 19/66/37 cases; preoperative hemoglobin levels were 118.5 ± 13.2 g/L and 116.8 ± 14.5 g/L; albumin levels were 36.8 ± 3.5 g/L and 37.2 ± 3.3 g/L; and surgical approach (open/Laparoscopic) distribution was 69/49 cases and 72/50 cases. There were no statistically significant differences between the two groups in any of these baseline characteristics (P > 0.05). Preoperative sleep quality assessment showed that the mean PSQI score was 9.8 ± 2.6 in the EEG group and 10.1 ± 2.4 in the control group, with no statistically significant difference (P = 0.367); PSQI component scores (sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction) also showed no significant differences between the groups. Regarding preoperative anxiety and depression scores, the EEG group had HADS-A scores of 5.8 ± 1.9 and HADS-D scores of 6.0 ± 1.8; the control group had HADS-A scores of 5.7 ± 2.0 and HADS-D scores of 5.9 ± 1.7, with no statistically significant differences between the groups (P > 0.05). Surgery-related baseline indicators such as expected operation time, anesthesia risk assessment results, and preoperative medication use were also comparable between the two groups (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Electroencephalogram group | Control group | Statistical value | P value |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 72.3 ± 5.7 | 71.8 ± 6.1 | t = 0.642 | 0.521 |

| Gender | χ² = 0.039 | 0.843 | ||

| Male | 75 (63.6) | 79 (64.8) | ||

| Female | 43 (36.4) | 43 (35.2) | ||

| Body mass index (kg/m²) (mean ± SD) | 23.5 ± 2.8 | 23.2 ± 3.0 | t = 0.779 | 0.437 |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| American Society of Anesthesiologists classification | χ² = 0.415 | 0.520 | ||

| Grade II | 72 (61.0) | 69 (56.6) | ||

| Grade III | 46 (39.0) | 53 (43.4) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 55 (46.6) | 59 (48.4) | χ² = 0.074 | 0.786 |

| Diabetes | 36 (30.5) | 40 (32.8) | χ² = 0.146 | 0.702 |

| Coronary heart disease | 26 (22.0) | 30 (24.6) | χ² = 0.221 | 0.639 |

| Preoperative laboratory tests | ||||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) (mean ± SD) | 118.5 ± 13.2 | 116.8 ± 14.5 | t = 0.946 | 0.345 |

| Albumin (g/L) (mean ± SD) | 36.8 ± 3.5 | 37.2 ± 3.3 | t = -0.897 | 0.371 |

| Tumor characteristics | ||||

| TNM staging | χ² = 0.378 | 0.828 | ||

| Stage I | 32 (27.1) | 30 (24.6) | ||

| Stage II | 51 (43.2) | 53 (43.4) | ||

| Stage III | 35 (29.7) | 39 (32.0) | ||

| Tumor location | χ² = 0.267 | 0.875 | ||

| Cardia | 28 (23.7) | 31 (25.4) | ||

| Body | 45 (38.1) | 43 (35.2) | ||

| Antrum | 45 (38.1) | 48 (39.3) | ||

| Differentiation degree | χ² = 0.199 | 0.905 | ||

| Well differentiated | 21 (17.8) | 19 (15.6) | ||

| Moderately differentiated | 62 (52.5) | 66 (54.1) | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 35 (29.7) | 37 (30.3) | ||

| Surgery-related | ||||

| Surgical approach | χ² = 0.018 | 0.892 | ||

| Open | 69 (58.5) | 72 (59.0) | ||

| Laparoscopic | 49 (41.5) | 50 (41.0) | ||

| Preoperative assessment | ||||

| PSQI total score (mean ± SD) | 9.8 ± 2.6 | 10.1 ± 2.4 | t = -0.904 | 0.367 |

| PSQI component scores (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Sleep quality | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | t = -0.823 | 0.411 |

| Sleep latency | 1.7 ± 0.7 | 1.8 ± 0.6 | t = -0.736 | 0.463 |

| Sleep duration | 1.6 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | t = -0.871 | 0.385 |

| Sleep efficiency | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.6 ± 0.5 | t = -0.802 | 0.424 |

| Sleep disturbances | 1.9 ± 0.4 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | t = 0.645 | 0.520 |

| Use of sleep medication | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.6 ± 0.7 | t = -0.600 | 0.549 |

| Daytime dysfunction | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | t = -0.851 | 0.395 |

| HADS scores (mean ± SD) | ||||

| Anxiety subscale (HADS-A) | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | t = 0.401 | 0.689 |

| Depression subscale (HADS-D) | 6.0 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.7 | t = 0.444 | 0.657 |

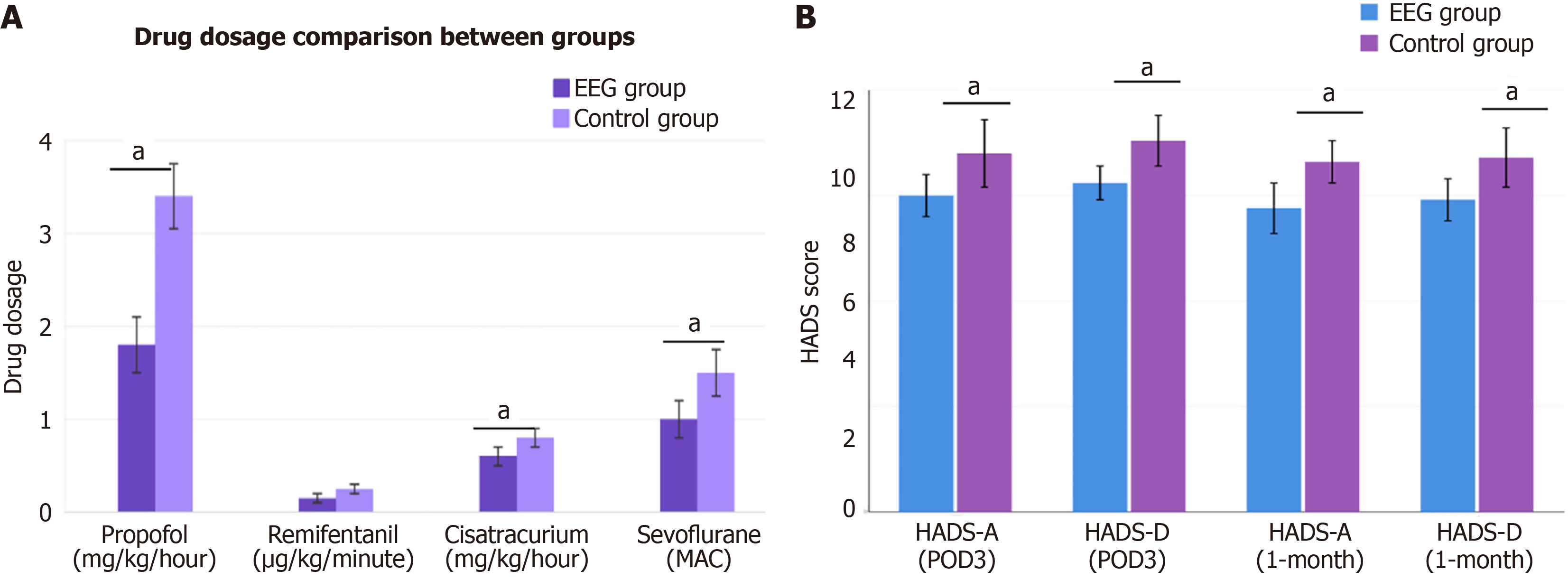

This study demonstrated that EEG-guided individualized anesthesia was significantly superior to conventional anesthesia management in terms of drug usage, hemodynamic stability, and cost-effectiveness. Regarding anesthetic drug consumption, the EEG group used significantly lower doses than the control group, including total propofol usage (5.8 ± 1.2 mg/kg/hour vs 7.3 ± 1.4 mg/kg/hour), total remifentanil usage (0.18 ± 0.04 μg/kg/minute vs 0.24 ± 0.05 μg/kg/minute), and total cisatracurium usage (0.42 ± 0.08 mg/kg/hour vs 0.51 ± 0.09 mg/kg/hour), all showing significant differences (all P < 0.001). For patients using sevoflurane, the EEG group also had significantly lower average minimum alveolar concentration values (0.72 ± 0.11 vs 0.88 ± 0.13), resulting in approximately 18.6% reduction in anesthesia costs. In terms of anesthetic timing, both groups had similar anesthesia induction times (EEG group: 6.8 ± 1.4 minutes vs control group: 7.1 ± 1.5 minutes), but the EEG group had significantly shorter recovery times (12.3 ± 3.5 minutes vs 15.7 ± 4.3 minutes). The EEG group maintained excellent BIS values with an average of 46.5 ± 4.2, and the proportion of time maintained within the target range reached 92.6% ± 5.1%. Regarding hemodynamic stability, the EEG group had a significantly lower incidence of intraoperative hypotension (22.0%) compared to the control group (37.7%), with shorter duration of hypotension (8.3 ± 2.7 minutes vs 12.5 ± 3.6 minutes). Correspondingly, the EEG group also had significantly reduced vasopressor usage rates (25.4% vs 41.0%). There were no significant differences between groups in bradycardia incidence or temperature maintenance (Figure 1A).

This multivariate regression analysis identified several independent protective and risk factors for postoperative psychological outcomes. Among the protective factors, EEG-guided individualized anesthesia emerged as the most significant protective factor with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.56 (95%CI: 0.41-0.78, P = 0.003), indicating a 44% reduction in risk. Reasonable preoperative psychological preparation also provided significant protection with an OR of 0.65 (95%CI: 0.45-0.94, P = 0.022). Good postoperative pain control (resting VAS < 4) showed a trend toward protection but did not reach statistical significance (OR = 0.74, P = 0.067). Several risk factors were identified that significantly increased the likelihood of poor postoperative psychological outcomes. The strongest risk factor was preoperative HADS score ≥ 8, more than doubling the risk (OR = 2.15, 95%CI: 1.42-3.26, P < 0.001). Preoperative PSQI score ≥ 10 nearly doubled the risk (OR = 1.87, 95%CI: 1.26-2.78, P = 0.002). Intraoperative factors also played important roles, with hypotension showing the highest risk among perioperative complications (OR = 1.75, 95%CI: 1.18-2.61, P = 0.006), followed by prolonged operation time > 3 hours (OR = 1.68, P = 0.010), excessive blood loss > 300 mL (OR = 1.52, P = 0.021), and hypothermia < 36.0 °C (OR = 1.46, P = 0.024). Patient-related factors including advanced age ≥ 75 years also increased risk (OR = 1.43, P = 0.038), while ASA III status showed a trend but did not reach statistical significance (OR = 1.39, P = 0.072). These findings emphasize that both preoperative psychological status and intraoperative management significantly influence postoperative psychological outcomes, with EEG-guided anesthesia providing substantial protective benefits. Among individual PSQI components, poor sleep efficiency (≤ 75%) was associated with the highest risk (OR = 2.24, 95%CI: 1.48-3.39, P < 0.001), followed by frequent sleep disturbances (≥ 2.5 points) (OR = 1.95, 95%CI: 1.32-2.88, P = 0.001), suggesting that sleep architecture disruption may be more predictive than sleep duration alone (Table 2).

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P value |

| Protective factors | |||

| Electroencephalogram-guided individualized anesthesia | 0.56 | 0.41-0.78 | 0.003 |

| Reasonable preoperative psychological preparation | 0.65 | 0.45-0.94 | 0.022 |

| Good postoperative pain control (resting Visual Analog Scale < 4) | 0.74 | 0.53-1.02 | 0.067 |

| Risk factors | |||

| Preoperative psychological factors | |||

| Preoperative Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale score ≥ 8 | 2.15 | 1.42-3.26 | < 0.001 |

| Preoperative PSQI score ≥ 10 | 1.87 | 1.26-2.78 | 0.002 |

| Individual PSQI components | |||

| Poor sleep efficiency (≤ 75%) | 2.24 | 1.48-3.39 | < 0.001 |

| Frequent sleep disturbances (≥ 2.5 points) | 1.95 | 1.32-2.88 | 0.001 |

| Patient-related factors | |||

| Age ≥ 75 years | 1.43 | 1.02-2.01 | 0.038 |

| American Society of Anesthesiologists III | 1.39 | 0.97-1.98 | 0.072 |

| Intraoperative factors | |||

| Intraoperative hypotension | 1.75 | 1.18-2.61 | 0.006 |

| Operation time > 3 hours | 1.68 | 1.13-2.49 | 0.010 |

| Intraoperative blood loss > 300 mL | 1.52 | 1.06-2.17 | 0.021 |

| Intraoperative temperature < 36.0 °C | 1.46 | 1.05-2.03 | 0.024 |

Based on the subgroup analysis results of HADS scores on postoperative day 3, EEG-guided individualized anesthesia showed significantly different effects on improving postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with varying severities of sleep disorders. In patients with severe sleep disorders, the EEG group demonstrated the most significant therapeutic effects, with anxiety scores (HADS-A) of 5.9 ± 1.8 points, markedly lower than the control group's 8.6 ± 2.1 points (t = -5.32, P < 0.001); depression scores (HADS-D) of 6.4 ± 1.6 points, also significantly lower than the control group's 8.2 ± 1.9 points (t = -4.06, P < 0.001); and total scores reaching 12.3 ± 3.1 points, showing substantial improvement compared to the control group's 16.8 ± 3.4 points (t = -5.48, P < 0.001). For patients with moderate sleep disorders, the EEG group's total score was 10.7 ± 2.9 points compared to the control group's 14.2 ± 3.2 points, with the difference between groups being statistically significant (t = -5.67, P < 0.001). In patients with mild sleep disorders, although the EEG group still outperformed the control group across all measures, the improvement magnitude was relatively smaller: (1) Anxiety scores of 4.5 ± 1.7 points vs 5.3 ± 1.9 points (t = -2.04, P = 0.045); (2) Depression scores of 5.0 ± 1.5 points vs 6.4 ± 1.7 points (t = -4.03, P < 0.001); and (3) Total scores of 9.5 ± 2.6 points vs 11.7 ± 2.8 points (t = -3.64, P = 0.023). These results indicate that patients with more severe preoperative sleep disorders derive greater benefits from EEG-guided individualized anesthesia, demonstrating a clear dose-response relationship (Table 3).

| Sleep disorder severity | Measure | Electroencephalogram group | Control group | t value | P value |

| Severe | HADS-A | 5.9 ± 1.8 | 8.6 ± 2.1 | -5.32 | < 0.001 |

| HADS-D | 6.4 ± 1.6 | 8.2 ± 1.9 | -4.06 | < 0.001 | |

| HADS total | 12.3 ± 3.1 | 16.8 ± 3.4 | -5.48 | < 0.001 | |

| Moderate | HADS total | 10.7 ± 2.9 | 14.2 ± 3.2 | -5.67 | < 0.001 |

| Mild | HADS-A | 4.5 ± 1.7 | 5.3 ± 1.9 | -2.04 | 0.045 |

| HADS-D | 5.0 ± 1.5 | 6.4 ± 1.7 | -4.03 | < 0.001 | |

| HADS total | 9.5 ± 2.6 | 11.7 ± 2.8 | -3.64 | 0.023 |

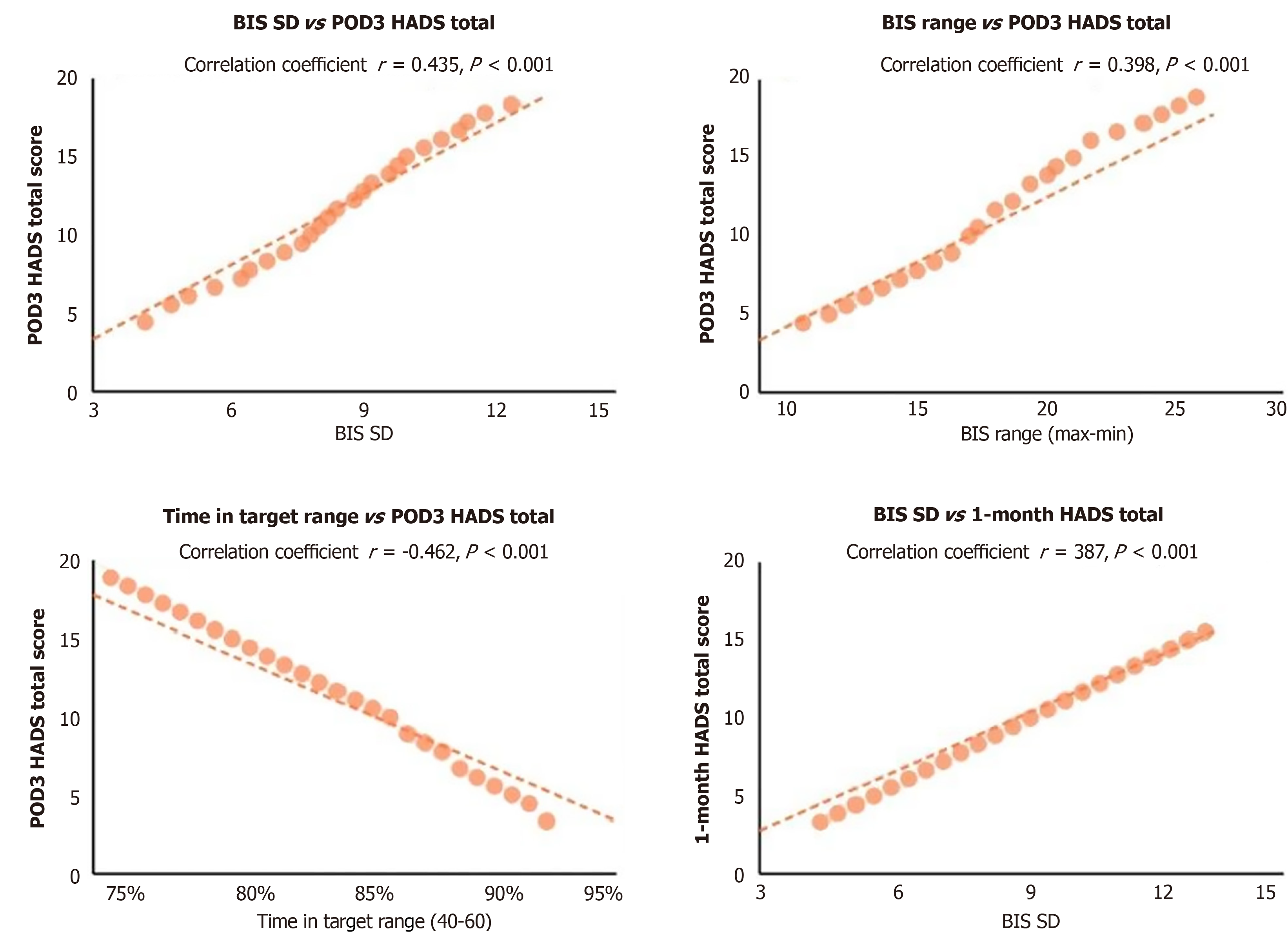

Internal analysis within the EEG group revealed significant correlations between BIS value stability and postoperative psychological outcomes. BIS standard deviation was positively correlated with postoperative anxiety and depression scores (postoperative day 3 HADS total score: r = 0.435, P < 0.001; 1-month HADS total score: r = 0.387, P < 0.001). Con

Postoperative anxiety and depression assessment showed that the EEG group had significantly better psychological outcomes than the control group. At 3 days postoperatively, the EEG group had lower HADS-A scores (5.6 ± 2.1 vs 7.8 ± 2.4, P < 0.001), HADS-D scores (6.2 ± 1.9 vs 8.1 ± 2.5, P < 0.001), and HADS total scores (11.8 ± 3.7 vs 15.9 ± 4.9, P < 0.001). The proportion of patients with clinically significant symptoms (HADS total ≥ 8) was lower in the EEG group (39.0% vs 62.3%, P < 0.001).

At 1-month follow-up, the EEG group continued to show superior outcomes with lower HADS total scores (8.7 ± 3.2 vs 13.2 ± 4.1, P < 0.001) and fewer patients with significant symptoms (21.2% vs 45.9%, P < 0.001). The incidence of severe anxiety (HADS-A ≥ 11) was significantly lower in the EEG group at both 3 days (13.6% vs 27.0%, P = 0.008) and 1 month (5.9% vs 16.4%, P = 0.009). Similarly, severe depression rates (HADS-D ≥ 11) were lower in the EEG group at 3 days (9.3% vs 20.5%, P = 0.014) and 1 month (4.2% vs 13.9%, P = 0.010). Multiple linear regression analysis confirmed that EEG-guided anesthesia remained significantly associated with improved postoperative HADS total scores (β = -3.54, 95%CI:

This outcome analysis demonstrated that EEG-guided anesthesia provided significant clinical benefits compared to conventional anesthesia management.

Postoperative complications: The EEG group had lower overall complication rates (32.2% vs 48.4%, P = 0.010), including reduced postoperative delirium (8.5% vs 17.2%, P = 0.038) with shorter duration, less nausea and vomiting (25.4% vs 37.7%, P = 0.039), fewer hypotensive episodes (13.6% vs 24.6%, P = 0.028), and lower pulmonary infection rates (5.1% vs 12.3%, P = 0.048).

Pain and recovery: Pain control was superior in the EEG group with consistently lower VAS scores across all postoperative days (all P < 0.001) and reduced analgesic consumption (45.3 ± 12.8 mg morphine equivalent vs 58.7 ± 16.2 mg morphine equivalent, P < 0.001). Gastrointestinal recovery was faster with earlier return of bowel sounds, first flatus, and liquid diet tolerance (all P < 0.001). Early ambulation was enhanced with sooner out-of-bed activity (26.8 ± 7.6 hours vs 32.5 ± 9.2 hours, P < 0.001) and better functional capacity.

Hospitalization outcomes: These improvements resulted in shorter hospital stays, with reduced total length of stay (12.6 ± 3.2 days vs 14.8 ± 3.5 days, P = 0.012) and postoperative length of stay (10.8 ± 2.7 days vs 12.5 ± 3.0 days, P < 0.001). While 30-day readmission rates were lower in the EEG group (3.4% vs 6.6%), this difference was not statistically significant. These results indicate that EEG-guided anesthesia enhances overall perioperative recovery, reduces complications, and optimizes resource utilization beyond just improving psychological outcomes (Table 4).

| Outcome | Electroencephalogram group | Control group | Statistic | P value |

| Postoperative complications | ||||

| Overall complication rate | 38 (32.2) | 59 (48.4) | χ² = 6.72 | 0.010 |

| Postoperative delirium | 10 (8.5) | 21 (17.2) | χ² = 4.31 | 0.038 |

| Duration of delirium (days) (mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.9 | t = -2.62 | 0.014 |

| Postoperative nausea and vomiting | 30 (25.4) | 46 (37.7) | χ² = 4.27 | 0.039 |

| Number of vomiting episodes (mean ± SD) | 1.3 ± 0.6 | 2.2 ± 1.0 | t = -5.05 | < 0.001 |

| Perioperative hypotension | 16 (13.6) | 30 (24.6) | χ² = 4.85 | 0.028 |

| Pulmonary infection | 6 (5.1) | 15 (12.3) | χ² = 3.92 | 0.048 |

| Wound infection | 7 (5.9) | 9 (7.4) | χ² = 0.19 | 0.659 |

| Urinary tract infection | 4 (3.4) | 7 (5.7) | χ² = 0.76 | 0.384 |

| Pain management | ||||

| POD1 VAS score (at rest) (mean ± SD) | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | t = -4.65 | < 0.001 |

| POD1 VAS score (with movement) (mean ± SD) | 5.1 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 1.5 | t = -3.73 | < 0.001 |

| POD2 VAS score (at rest) (mean ± SD) | 2.5 ± 0.9 | 3.0 ± 1.1 | t = -3.89 | < 0.001 |

| POD2 VAS score (with movement) (mean ± SD) | 4.2 ± 1.3 | 4.9 ± 1.4 | t = -4.02 | < 0.001 |

| POD3 VAS score (at rest) (mean ± SD) | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | t = -3.46 | 0.001 |

| POD3 VAS score (with movement) (mean ± SD) | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 4.1 ± 1.2 | t = -3.34 | 0.001 |

| Cumulative analgesic consumption (morphine equivalent mg) (mean ± SD) | 45.3 ± 12.8 | 58.7 ± 16.2 | t = -7.24 | < 0.001 |

| Gastrointestinal recovery | ||||

| Time to first bowel sounds (hours) (mean ± SD) | 46.5 ± 12.8 | 53.2 ± 14.5 | t = -3.82 | < 0.001 |

| Time to first flatus (hours) (mean ± SD) | 62.3 ± 15.6 | 70.8 ± 16.9 | t = -4.04 | < 0.001 |

| Time to first liquid diet (days) (mean ± SD) | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | t = -4.53 | < 0.001 |

| Early ambulation | ||||

| Time to first out-of-bed activity (hours) (mean ± SD) | 26.8 ± 7.6 | 32.5 ± 9.2 | t = -5.21 | < 0.001 |

| 6-minute walking test on POD3 (m) (mean ± SD) | 152.6 ± 45.8 | 128.3 ± 40.6 | t = 4.28 | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization outcomes | ||||

| Total length of stay (days) (mean ± SD) | 12.6 ± 3.2 | 14.8 ± 3.5 | t = -5.05 | 0.012 |

| Postoperative length of stay (days) (mean ± SD) | 10.8 ± 2.7 | 12.5 ± 3.0 | t = -4.58 | < 0.001 |

| 30-day readmission rate | 4 (3.4) | 8 (6.6) | χ² = 1.29 | 0.256 |

Elderly gastric cancer patients represent a special high-risk population whose perioperative management faces numerous challenges. With the accelerating aging population, the number of elderly gastric cancer patients continues to increase, creating higher demands for optimized perioperative management strategies for these patients[16-18]. Preoperative sleep disorders are common problems among elderly gastric cancer patients, with approximately 60%-75% experiencing various sleep problems, including difficulty falling asleep, sleep interruptions, early awakening, and decreased sleep quality. These issues not only reduce patients' quality of life but may also negatively impact perioperative management and prognosis[19-21].

There is a close association between sleep disorders and anxiety-depression symptoms. Long-term sleep disorders can lead to pathophysiological changes including neurotransmitter imbalances, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, and elevated inflammatory factor levels, which increase patients' risk of developing postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms[22,23]. Additionally, elderly patients show higher sensitivity to anesthetic drugs, with decreased drug metabolism and clearance abilities, making them more susceptible to fluctuations in anesthesia depth and related adverse events. Traditional anesthesia depth monitoring primarily relies on clinical observation and conventional vital signs, which often lag behind actual changes in the central nervous system and have limited sensitivity and specificity in elderly patients. Anesthesia management based on conventional indicators may lead to inappropriate anesthesia depth in approximately 40% of elderly patients, including anesthesia that is either too deep or too shallow, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms[24-26].

There is a close connection between sleep disorders and EEG activity. Patients with chronic sleep disorders often exhibit enhanced alpha and beta wave activity and weakened delta and theta wave activity in their EEGs, reflecting abnormal cerebral cortical function[27]. These abnormalities may affect patients' sensitivity and responsiveness to anesthetic drugs, causing standard doses of anesthetics to produce different depths of anesthesia in different patients. EEG monitoring technology, particularly BIS monitoring, provides objective indicators for evaluating anesthesia depth through real-time analysis of EEG signals. BIS values range from 0 to 100, with 40-60 considered the ideal range for general anesthesia. Compared to traditional monitoring, EEG monitoring can more directly and promptly reflect the functional state of the central nervous system, providing an objective basis for individualized adjustment of anesthetic drugs[28-30].

Appropriate anesthesia depth not only affects intraoperative stability but may also influence postoperative recovery and long-term prognosis through various mechanisms, including regulation of neuroendocrine responses, inflammatory processes, and immune function. This is particularly important for elderly gastric cancer patients, who often have decreased multiple organ function reserves and chronic disease burdens. With the promotion of precision medicine concepts, individualized anesthesia management has received increasing attention, and EEG monitoring, as an important tool for achieving individualized anesthesia, warrants in-depth exploration of its application value in special populations[31-33].

This study systematically evaluated, for the first time, the impact of individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring on postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms in elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders. The results showed that, compared to conventional monitoring, patients in the EEG monitoring group had significantly reduced postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms, decreased postoperative delirium incidence, shortened hospital stays, and improved postoperative quality of life. Multivariate regression analysis confirmed that individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring was an independent protective factor for improvement of postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms (OR = 0.56, 95%CI: 0.41-0.78, P = 0.003). This finding has important clinical significance, indicating that by optimizing anesthesia management strategies, the postoperative psychological health status of elderly gastric cancer patients can be significantly improved.

Another important finding of this study was the significant correlation between BIS value stability and postoperative psychological outcomes. BIS value standard deviation was significantly positively correlated with postoperative anxiety and depression scores, while the proportion of time maintained within the target range was significantly negatively correlated with postoperative anxiety and depression scores. This suggests that the stability of anesthesia depth, rather than absolute depth level, may be the key factor affecting postoperative neuropsychiatric symptoms. This finding aligns with recent research results on anesthesia depth fluctuations, suggesting that maintaining stable anesthesia depth may be more important than simply pursuing a specific depth.

Subgroup analysis revealed the differential impact of EEG monitoring on patients with varying degrees of sleep disorders. The protective effect of EEG monitoring was most significant in patients with severe sleep disorders (OR = 0.41), followed by those with moderate sleep disorders (OR = 0.58), and was relatively weak in patients with mild sleep disorders (OR = 0.72). This gradient effect suggests that patients with more severe preoperative sleep disorders derive greater benefits from individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring. This may be related to the higher sensitivity to anesthetic drugs and more pronounced EEG activity abnormalities in patients with severe sleep disorders, making them more susceptible to anesthesia depth instability and related complications under conventional monitoring.

This study also systematically analyzed, for the first time, the relationship between preoperative sleep disorder severity and anesthetic drug sensitivity. The results showed that as preoperative PSQI scores increased, patients' sensitivity to anesthetic drugs gradually increased, with patients with severe sleep disorders requiring significantly lower anesthetic drug dosages than those with mild disorders to achieve similar anesthesia depths. This finding provides important reference for anesthesia management, suggesting that when administering anesthetic drugs to elderly patients with preoperative sleep disorders, their sleep status should be considered, with appropriate dose adjustments to avoid drug overdose.

Additionally, this study found that EEG monitoring significantly reduced anesthetic drug usage, improved hemo

The mechanisms by which individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring improves postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms may be multifaceted: (1) Precise control of anesthesia depth, avoiding anesthesia that is too deep or too shallow, reducing the adverse effects of drug fluctuations on the brain; (2) Reducing total anesthetic drug usage, lowering drug-induced central nervous system suppression and inflammatory responses; (3) Improving hemodynamic stability, maintaining cerebral perfusion, reducing hypoxic neuronal damage; and (4) Accelerating awakening and recovery, shortening delirium states, promoting early activity and gastrointestinal function recovery, indirectly impro

Our findings provide strong evidence supporting the routine implementation of BIS monitoring in elderly cancer patients with sleep disorders. The demonstrated benefits extend beyond psychological outcomes to include reduced drug consumption, improved hemodynamic stability, and enhanced overall recovery profiles. Healthcare institutions should consider developing protocols for identifying high-risk patients through preoperative sleep assessment and imp

Despite the valuable findings of this study, some limitations exist. Most importantly, our single-center design may limit the generalizability of our findings. While this approach enhanced internal validity through standardized surgical techniques and consistent perioperative protocols, we acknowledge that this may constrain the external validity of our results. Our findings should be interpreted within the context of our specific institutional protocols and patient population characteristics. Future multicenter studies will be valuable for validating our findings across different patient populations and healthcare settings, as variations in surgical techniques, perioperative care protocols, and patient demographics may influence the magnitude of benefits observed with EEG-guided anesthesia.

Additionally, as a retrospective study, selection bias and confounding factors cannot be completely eliminated, though our comprehensive baseline matching and multivariate analysis help mitigate these concerns. The postoperative follow-up period was relatively short, preventing assessment of long-term neuropsychiatric outcomes beyond one month. Finally, while we identified sleep efficiency and sleep disturbances as the most predictive PSQI components, the study did not deeply explore the interaction between EEG monitoring and different subtypes of sleep disorders, which warrants investigation in future prospective studies.

This study demonstrates that for elderly gastric cancer patients with preoperative sleep disorders, individualized anesthesia guided by EEG monitoring can significantly reduce postoperative anxiety and depression symptoms, lower postoperative delirium risk, shorten hospital stays, and improve postoperative quality of life. This protective effect is most pronounced in patients with severe sleep disorders, suggesting the special value of EEG monitoring in high-risk populations.

| 1. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Chao J, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Fanta P, Farjah F, Gerdes H, Gibson MK, Hochwald S, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Keswani RN, Kim S, Kleinberg LR, Klempner SJ, Lacy J, Ly QP, Matkowskyj KA, McNamara M, Mulcahy MF, Outlaw D, Park H, Perry KA, Pimiento J, Poultsides GA, Reznik S, Roses RE, Strong VE, Su S, Wang HL, Wiesner G, Willett CG, Yakoub D, Yoon H, McMillian N, Pluchino LA. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2022;20:167-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 1163] [Article Influence: 290.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guan WL, He Y, Xu RH. Gastric cancer treatment: recent progress and future perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2023;16:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Gullo I, Grillo F, Mastracci L, Vanoli A, Carneiro F, Saragoni L, Limarzi F, Ferro J, Parente P, Fassan M. Precancerous lesions of the stomach, gastric cancer and hereditary gastric cancer syndromes. Pathologica. 2020;112:166-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Hall CE, Maegawa F, Patel AD, Lin E. Management of Gastric Cancer. Am Surg. 2023;89:2713-2720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xiao Y, Zhao Z, Su CG, Li J, Liu J. An interpretable machine learning model for predicting depression in middle-aged and elderly cancer patients in China: a study based on the CHARLS cohort. BMC Psychiatry. 2025;25:610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Machlowska J, Baj J, Sitarz M, Maciejewski R, Sitarz R. Gastric Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Genomic Characteristics and Treatment Strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:4012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 969] [Article Influence: 161.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hu LY, Liu CJ, Yeh CM, Lu T, Hu YW, Chen TJ, Chen PM, Lee SC, Chang CH. Depressive disorders among patients with gastric cancer in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Matsuoka T, Yashiro M. Novel biomarkers for early detection of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2515-2533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Petryszyn P, Chapelle N, Matysiak-Budnik T. Gastric Cancer: Where Are We Heading? Dig Dis. 2020;38:280-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 3294] [Article Influence: 549.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 11. | Thrift AP, El-Serag HB. Burden of Gastric Cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 1076] [Article Influence: 179.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 12. | Xia JY, Aadam AA. Advances in screening and detection of gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2022;125:1104-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Yang WJ, Zhao HP, Yu Y, Wang JH, Guo L, Liu JY, Pu J, Lv J. Updates on global epidemiology, risk and prognostic factors of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:2452-2468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 103.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (14)] |

| 14. | Yasuda T, Wang YA. Gastric cancer immunosuppressive microenvironment heterogeneity: implications for therapy development. Trends Cancer. 2024;10:627-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zeng Y, Jin RU. Molecular pathogenesis, targeted therapies, and future perspectives for gastric cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86:566-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Li J, Ma C. Anxiety and depression during 3-year follow-up period in postoperative gastrointestinal cancer patients: prevalence, vertical change, risk factors, and prognostic value. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:2621-2629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yoon K, Shin CM, Han K, Jung JH, Jin EH, Lim JH, Kang SJ, Choi YJ, Lee DH. Risk of cancer in patients with insomnia: Nationwide retrospective cohort study (2009-2018). PLoS One. 2023;18:e0284494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zhan LH, Dong YJ, Yang K, Lei SS, Li B, Teng X, Zhou C, Luo R, Yu QX, Jin HY, Lv GY, Chen SH. Soporific Effect of Modified Suanzaoren Decoction and Its Effects on the Expression of CCK-8 and Orexin-A. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:6984087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chung JW, Kim N, Wee JH, Lee J, Lee J, Kwon S, Hwang YJ, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Kim JW. Clinical features of snoring patients during sedative endoscopy. Korean J Intern Med. 2019;34:305-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Janić M, Škrgat S, Harlander M, Lunder M, Janež A, Pantea Stoian A, El-Tanani M, Maggio V, Rizzo M. Potential Use of GLP-1 and GIP/GLP-1 Receptor Agonists for Respiratory Disorders: Where Are We at? Medicina (Kaunas). 2024;60:2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Katayama ES, Woldesenbet S, Munir MM, Endo Y, Rawicz-Pruszyński K, Khan MMM, Tsilimigras D, Dillhoff M, Cloyd J, Pawlik TM. Effect of Behavioral Health Disorders on Surgical Outcomes in Cancer Patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2024;238:625-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang Z, Jiang C, Yin B, Wang H, Zong J, Yang T, Zou L, Dong Z, Chen Y, Wang S, Qu X. Investigating the causal links between obstructive sleep apnea and gastrointestinal diseases mediated by metabolic syndrome through mendelian randomization. Sci Rep. 2024;14:26247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kwon S, Kim J, Kim T, Jeong W, Park EC. Association between gastric cancer and the risk of depression among South Korean adults. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bai L, Shi Y, Zhou S, Gong L, Zhang L, Tian J. Intervention model under the Omaha system framework can effectively improve the sleep quality and negative emotion of patients with mid to late-stage lung cancer and is a protective factor for quality of life. Am J Cancer Res. 2024;14:1278-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Loosen S, Krieg S, Krieg A, Leyh C, Luedde T, Vetter C, Kostev K, Roderburg C. Are sleep disorders associated with the risk of gastrointestinal cancer?-A case-control study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:11369-11378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mogavero MP, DelRosso LM, Fanfulla F, Bruni O, Ferri R. Sleep disorders and cancer: State of the art and future perspectives. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;56:101409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhuang J, Yu J, Yang Y. Association of GAB2 with Quality of Life and Negative Emotions in Patients with Gastric Cancer after Postoperative Comprehensive Care. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:1732214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Nguyen LT, Dang AK, Duong PT, Phan HBT, Pham CTT, Nguyen ATL, Le HT. Nutrition intervention is beneficial to the quality of life of patients with gastrointestinal cancer undergoing chemotherapy in Vietnam. Cancer Med. 2021;10:1668-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pham AT, Do MT, Tran HTT. A cross-sectional study of sleep disturbance among middle-aged cancer patients at Vietnam National Cancer Hospital. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2024;7:e2055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tan BKJ, Teo YH, Tan NKW, Yap DWT, Sundar R, Lee CH, See A, Toh ST. Association of obstructive sleep apnea and nocturnal hypoxemia with all-cancer incidence and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2022;18:1427-1440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tang WW, Han ML, Xu SH, Deng YX, Shen Q. Analysis of sleep quality, disease uncertainty, and psychological tolerance in patients undergoing chemotherapy for digestive tract malignancies. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:4247-4255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Du D, Zhang G, Xu D, Liu L, Hu X, Chen L, Li X, Shen Y, Wen F. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of sleep disorders in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2023;112:282-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wei J, Yan H, Yin W, He F. The change of symptom clusters in gastric cancer patients during the perioperative period: a longitudinal study. Support Care Cancer. 2024;32:387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/