Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112462

Revised: August 20, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 186 Days and 1.6 Hours

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) requires optimal muscle relaxation, which is conventionally achieved with succinylcholine (SCC) despite its adverse effects. In this context, rocuronium-sugammadex (RS) has emerged as a potential alterna

To compare the recovery times, seizure duration, and side effect profiles of RS and SCC in ECT.

PubMed, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library (from inception to June 2025) were systematically searched for randomized and observational studies comparing RS with SCC in ECT. The primary outcomes were seizure duration (motor/electroencephalogram) and recovery time, and the secondary outcomes included adverse events (e.g., myalgia). Pooled standardized mean differences (SMDs) and risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using random-effects models.

This meta-analysis included 7 studies involving 250 observations of patients who received RS and 282 sessions in which patients received SCC. Regarding seizure duration required for effective ECT, RS was associated with a longer duration (SMD: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.15-0.70, P < 0.05). However, this effect became nonsignificant in analyses limited to randomized controlled trials (SMD: 0.54, 95%CI: -0.17 to 1.25, P > 0.05). No significant difference was found between the groups in the recovery time (SMD: -0.51, 95%CI: -1.57 to 0.56, P = 0.277), despite trends favoring RS in three out of six studies. Qualitatively, the RS combination was associated with fewer adverse events, such as myalgia, although the reporting was inconsistent across studies. Substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89%-93%) was a key finding for recovery outcomes, likely stemming from variability in the dosing and procedural protocols.

RS is a feasible alternative to SCC for ECT, with acceptable recovery and fewer side effects without affecting the seizure duration. However, larger high-quality randomized controlled trials are necessary to statistically sub

Core Tip: Based on the meta-analysis, rocuronium-sugammadex (RS) may be associated with a statistically longer seizure duration in the overall analyses, although this effect was not significant in randomized studies. No significant difference was found in recovery time compared to succinylcholine, despite some trends favoring the use of RS. Qualitatively, RS appears to have a better safety profile, with fewer adverse events such as myalgia. However, the high heterogeneity in recovery outcomes emphasizes the need for more standardized research protocols to yield more consistent and definitive conclusions.

- Citation: Anand R, Nag DS, Gope RL, Sahoo MK, Bhushan P, Pal BD, Patel R, Shivani S, Bharadwaj MK, Ansari MA. Rocuronium-sugammadex as an alternative muscle relaxant to succinylcholine in electroconvulsive therapy: A meta-analysis. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 112462

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/112462.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112462

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective and potentially life-saving treatment modality for several severe psy

In recent years, the combination of rocuronium-sugammadex (RS) has emerged as a promising alternative. Rocu

Despite increasing interest and anecdotal reports of its use in ECT, a comprehensive synthesis of evidence comparing SCC with RS combination in terms of efficacy is lacking. Particularly seizure duration, which is vital for ECT effectiveness, and safety profiles in the ECT context have not been adequately investigated. Individual case reports, studies, and literature reviews have reported mixed findings regarding seizure duration and varied outcomes for adverse events and recovery times[7]. Consequently, a meta-analysis is necessary for a robust and comprehensive quantitative compa

This meta-analysis aimed to systematically assess and compare the clinical outcomes of SCC and RS combination for muscle relaxation in patients undergoing ECT. The RS combination was hypothesized to provide similar efficacy in terms of seizure duration while offering a more favorable safety and recovery profile.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. The study protocol was registered in International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews 2025 (No. CRD420251 057315). Studies that satisfied the population, intervention, comparison, outcomes and study criteria were included (Table 1).

| Category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Population | Adults (≥ 18 years) undergoing ECT for psychiatric disorders | Pediatric populations |

| Intervention | Rocuronium (any dose) with sugammadex reversal | Other NMBA agents (e.g., atracurium and vecuronium) or reversal without sugammadex |

| Comparator | Succinylcholine (any dose) | Studies without a direct succinylcholine comparison group |

| Outcomes | Motor/EEG seizure duration, recovery time, adverse events | Studies not reporting relevant outcomes or with insufficient data for extraction |

| Study design | RCTs and observational studies (cohort, case-control study and case series) with comparator arms | Case reports, reviews, editorials, conference abstracts without full data and animal studies |

| Language | No restriction |

A systematic literature search of the PubMed, Web of Science, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases was conducted from their inception to June 30, 2025. The search terms included: “electroconvulsive therapy”, “ECT”, and “electroshock”; interventions: "rocuronium”, “sugammadex”; and the comparator “succinylcholine”. Two reviewers manually reviewed the reference lists of the relevant review articles and included the studies to identify additional eligible studies. Both observational and randomized studies were included to maximize the evidence base, given the limited number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

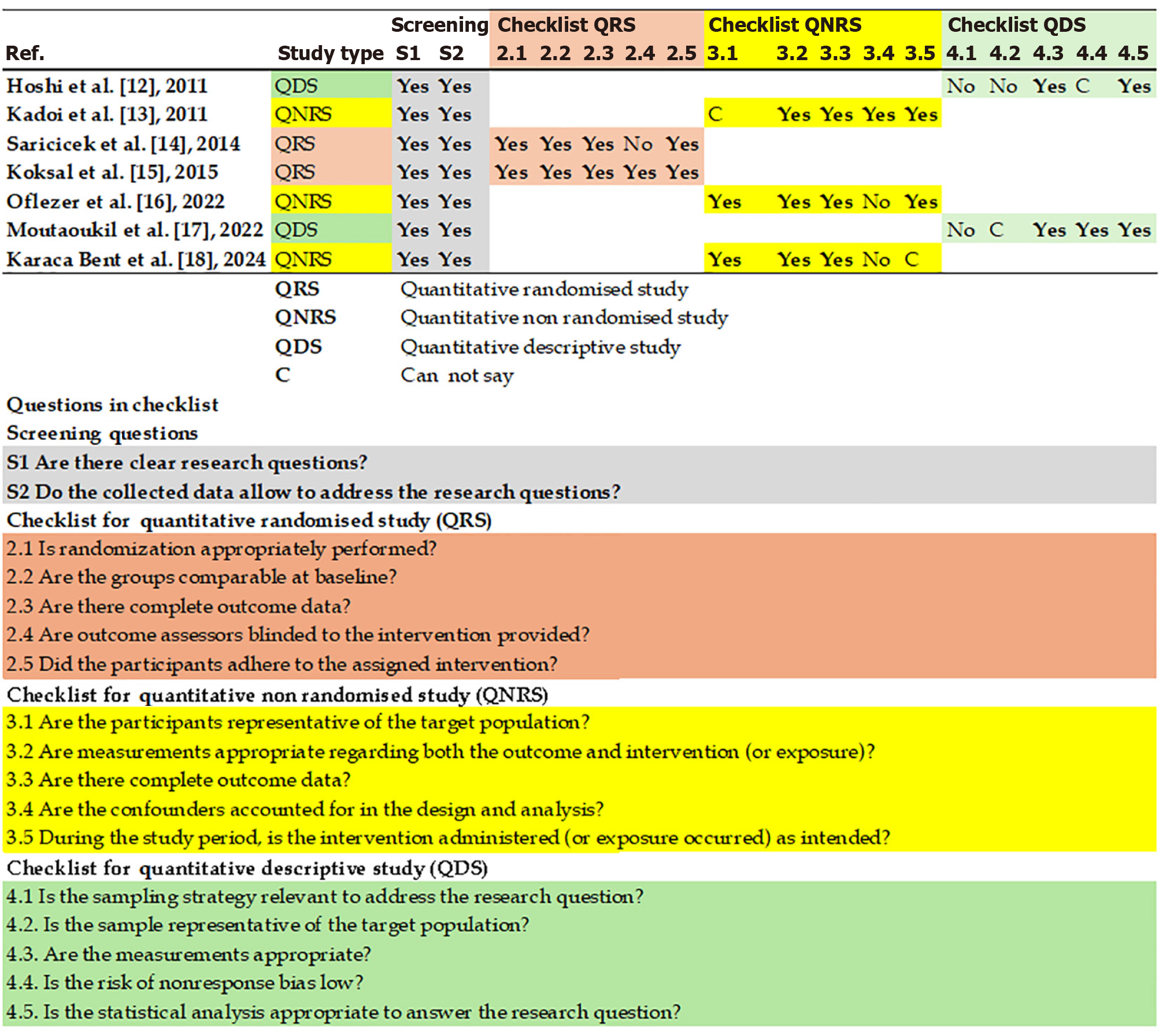

All search results were imported into the Zotero reference management software, and duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers screened the titles and abstracts according to predetermined eligibility criteria. Both reviewers retrieved the full texts of the selected studies and evaluated them for final inclusion. A third reviewer was consulted to resolve any disagreements at the screening and full-text review stages via discussion or arbitration. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias for each study using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018[9]. Conflicts were resolved via discussions or mediation by third-party reviewers.

Data were extracted using a piloted form that comprised the following elements: Study characteristics (including design, sample size, and country), patient demographics (such as age, diagnosis, and ECT parameters), intervention details (covering dosing and timing), and outcomes (expressed as mean ± SD for continuous variables and n/N for dichotomous variables).

Effect measures: For continuous outcomes, the standardized mean difference (SMD) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used. A random-effects model was used for all analyses, regardless of heterogeneity, as it accounted for both within-study and between-study variabilities. The Knapp-Hartung method was used for the tests and CIs. For dichotomous outcomes, the risk ratio (RR) with a 95%CI was used. Heterogeneity: Heterogeneity was assessed using τ2 (restricted maximum likelihood estimator), Cochran’s Q-test, and I2 statistic. For the I2 statistic, a value greater than 50% indicated substantial heterogeneity.

Pre-specified subgroup analyses included comparisons between RCTs and observational studies. Sensitivity analyses were planned, excluding studies with high influence if detected using Cook’s distance (median + 6 × interquartile range). Publication bias was determined using funnel plots and Egger’s tests. Microsoft Excel was utilized for data collection. Data was analyzed using the online web tool meta-analysis online[10], and the results were verified using the Jamovi statistical software package (Version 2.6.26).

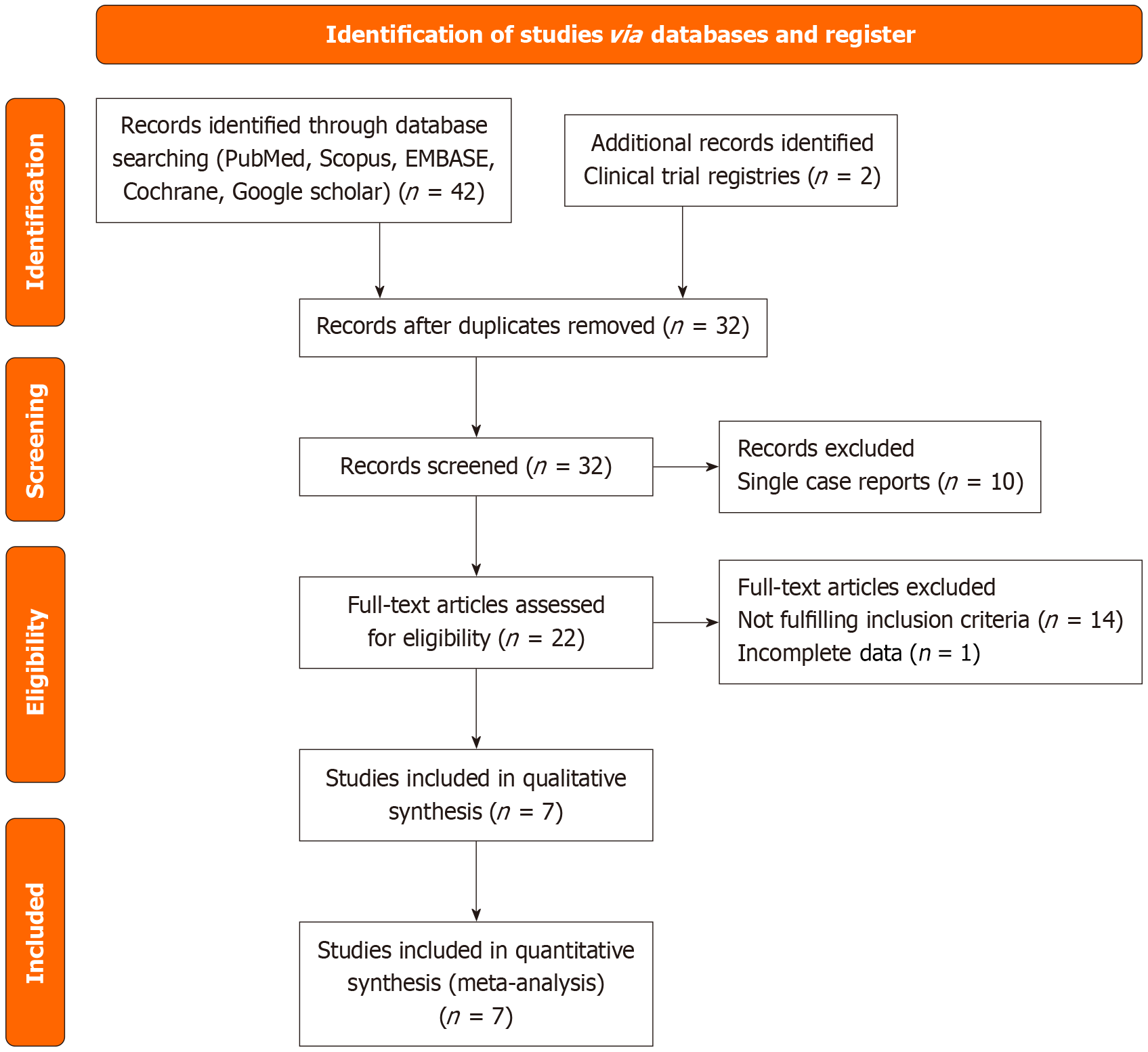

After protocol registration, two reviewers conducted a literature search between June 1, 2025, and June 30, 2025. They initially identified 42 records via database search. Two additional records were located in the clinical trial registries. Hence, a total of 44 records were screened (Figure 1). After removing the duplicates, the number of records was reduced to 31 articles. The initial screening excluded 10 single-case reports. Subsequently, 21 full-text articles were evaluated for eligibility, of which 14 were excluded as they failed to fulfill the inclusion criteria or reported insufficient data. Ultimately, seven studies were included in the qualitative meta synthesis, which formed the foundation for the meta-analysis (Figure 1)[11-17]. All studies were assessed for risk of bias using the MMAT, version 2018[9], and evaluations were based on the journal articles contents (Figure 2). The MMAT assessment revealed a moderate risk of bias in non-RCTs (e.g., lack of blinding). Therefore, sensitivity analyses were performed using subgroup analyses to exclude less scientifically rigorous studies before the final interpretation.

This meta-analysis synthesized data from 7 studies: Hoshi et al[11], Kadoi et al[12], Saricicek et al[13], Koksal et al[14], Oflezer et al[15], Moutaoukil et al[16], and Karaca Bent et al[17]. These studies encompassed 250 observations in the RS cohort and 282 in the SCC cohort (Table 2). The number of observations was contingent on the number of sessions conducted or observed in each study. In several studies, the subjects participated in multiple sessions, and they crossed over between the two groups. In studies where multiple doses were compared, the outcome data for the optimum combination, as suggested by the investigators, were used. ECT is a dynamic, multi-session intervention in which treat

| Ref. | Study design | Patients/ECT sessions | R dose | SG dose | SCC dose | Induction agent | Key outcomes measured |

| Hoshi et al[11] | Small observational case series, non-blinded muscle relaxant selection | 5 patients (every patient 3 with SCC and 4 with R + SCC) | 0.6 mg/kg | 16 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | Propofol 1.0 mg/kg | T1 10% and 90% recovery, time to first spontaneous breath, eye opening, seizure duration, adverse effects |

| Kadoi et al[12] | Clinical study, lottery system for sugammadex dose (non-blinded sugammadex administration) | 17 patients(3 session with different dose of SG and 4 sessions of SCC) | 0.6 mg/kg | 16 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, or 4 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | Propofol 1.0 mg/kg | T1 10% and 90% recovery, seizure duration, time to first spontaneous breath, adverse effects |

| Saricicek et al[13] | Randomized | 45 patients | 0.3 mg/kg | 4 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | Propofol 1 mg/kg | Myalgia VAS, headache VAS, time to T1, T2, motor seizure duration |

| Koksal et al[14] | Randomized, double-blind (for drug preparation) | 16 patients | 0.6 mg/kg | 4 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | Propofol 2 mg/kg | Spontaneous breathing time, eye opening time, time for obeying instructions, motor seizure duration, MAS and MAS 9 timing, T1 0% and T1 90% times, vital signs, side effects |

| Oflezer et al[15] | Single-center retrospective observational study | 134 patients | 0.3 mg/kg | 2 mg/kg | 0.5 mg/kg | Propofol 1 mg/kg | EEG seizure duration, motor seizure modification, CGI-I score, adverse effects, vital signs |

| Moutaoukil et al[16] | Small observational case series (prospectively collected) | 4 patients | 0.3 mg/kg | 4 mg/kg | 0.5 mg/kg | Propofol 1-1.5 mg/kg | Motor seizure modification, time to spontaneous breathing, time to eye opening, agitation, myalgia, headache, nausea/vomiting, EEG seizure duration |

| Karaca Bent et al[17] | Single-center observational cohort study (prospective collection, retrospective analysis) | 100 adult patients | 0.4 mg/kg | 2 mg/kg | 1 mg/kg | Propofol 1 mg/kg | Spontaneous breathing time, spontaneous eye opening, seizure duration, vital signs (BP, HR, SpO2) |

| Ref. | Main findings | Conclusion/recommendation |

| Hoshi et al[11] | Recovery: Time to spontaneous respiration 10% and 90% recovery tended to be shorter in the RS group, but the difference was not statistically significant; seizure duration: RS longer (39 seconds vs 33 seconds) | It shows potential benefits as an alternative to succinylcholine for muscle relaxation; side effects: No adverse effects were reported with either muscle relaxants |

| Kadoi et al[12] | Efficacy as an alternative to SCC; sugammadex (8 mg/kg) produces equally rapid recovery as SCC for 0.6 mg/kg of rocuronium | Sugammadex (8 mg/kg) produces equally rapid recovery as SCC; side effects: No adverse effects were reported |

| Saricicek et al[13] | Recovery: Group RS is significantly shorter for spontaneous respiration and eye-opening across all sessions; side effects: Myalgia and headache VAS scores were significantly lower in the RS group; seizure duration: No statistically significant difference was observed | It also causes reduced myalgia and headache, and faster recovery compared to succinylcholine |

| Koksal et al[14] | Recovery: Rocuronium + succinylcholine was significantly shorter for Modified Alderete Score 9 (7.26 minutes vs 11.26 minutes), Spontaneous eye opening (6.64 minutes vs 9.67 minutes), obeying instructions (8.10 minutes vs 11.72 minutes), spontaneous breathing (5.93 minutes vs 8.14 minutes), and time to spontaneous respiration 90% (4.87 minutes vs 9.95 minutes); onset: Group RS longer (149.40 seconds vs 111.53 seconds); seizure duration: Group RS longer (23.28 seconds vs 15.62 seconds) | Sufficient muscle relaxation and early recovery. It can be used as an alternative to succinylcholine |

| Oflezer et al[15] | EEG/motor seizure duration: Rocuronium + succinylcholine longer than succinylcholine (36.61 seconds vs 33.15 seconds; P = 0.002, P < 0.001 respectively); adverse effects: No major complications or deaths were reported in either group; CGI-I score: No significant difference | Similar results in terms of seizure variables and clinical outcomes can be a suitable alternative. |

| Moutaoukil et al[16] | Recovery: Rocuronium + succinylcholine was significantly shorter for spontaneous respiration (219 seconds vs 296 seconds) and eye opening (402 seconds vs 467 seconds); motor seizure modification: RS had a significantly higher (better) score (3.6 vs 3.0); side effects: Agitation (0% vs 16%) and myalgia (4% vs 33%) were significantly lower in the RS group; seizure duration: Comparable (40 seconds vs 38 seconds) | Efficacious alternative to succinylcholine, leading to faster recovery with less myalgia and agitation |

| Karaca Bent et al[17] | Recovery: RS was notably shorter for spontaneous breathing time (88.82 seconds vs 111.78 seconds), spontaneous eye opening (173.12 seconds vs 211.42 seconds), and Modified Alderete Score 9 (410.54 seconds vs 542.60 seconds); seizure duration: No significant difference | Sugammadex is an ideal alternative agent when succinylcholine is contraindicated, or anticholinesterases are not suitable; it shortens recovery time and spontaneous respiration |

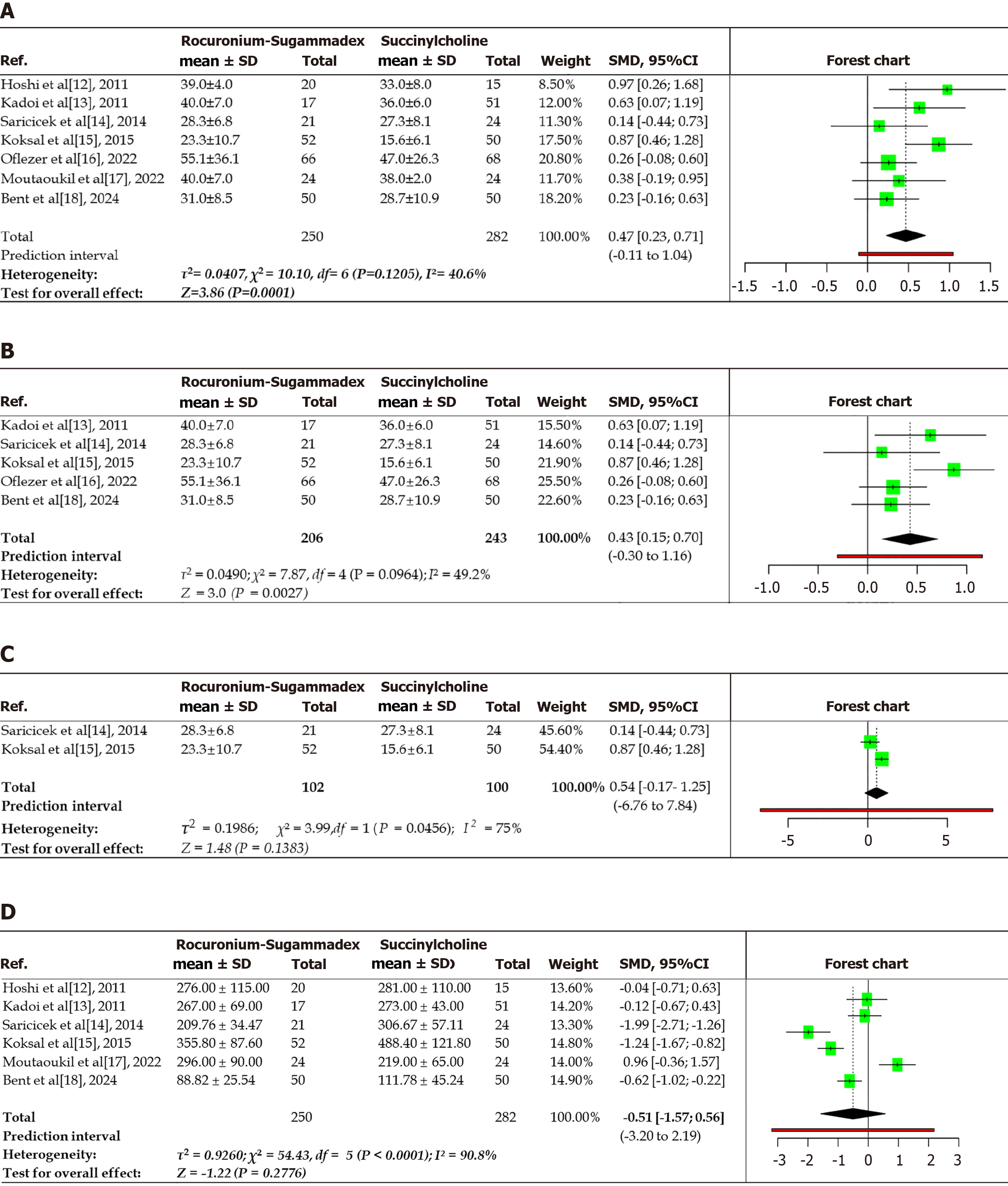

This meta-analysis included 7 studies with 250 observations in the RS cohort and 282 in the SCC cohort to assess seizure duration (electroencephalography or motor seizures). The total observations represented all recorded sessions across the included studies rather than unique patients. Each ECT session with recorded data was considered an independent ‘observation’ for quantitative pooling. This approach maximized the available data, particularly from studies with multiple sessions or crossovers between treatment groups. When using a random-effects model with inverse variance weighting, the pooled SMD in seizure duration was 0.43, with a 95%CI of 0.15-0.7, indicating a statistically significant prolongation of seizures in the RS group compared to the SCC group (P < 0.05; Figure 3A). The quantified heterogeneity was low to moderate [τ2 = 0.04 (95%CI: 0-0.45), τ = 0.20 (95%CI: 0-0.661), I2 = 40.6% (95%CI: 0%-74.4%), and H = 1.20 (95%CI: 1-2.007)]. Cochran’s Q test (Q = 10.16, degree of freedom = 6, P = 0.12) confirmed low heterogeneity across studies, with effect sizes showing consistent direction and magnitude. A random-effects model with the inverse variance method was used in the analysis to compare the SMD, which revealed a statistically significant difference between the two cohorts. A subgroup analysis was performed for seizure duration, which included five studies after excluding quantitative descriptive studies. This analysis included 206 and 243 participants in the experimental (RS) and control (SCC) groups, respectively (Figure 3B). A random-effects model with the inverse variance method was employed to compare the SMD, which revealed a statistical difference between the two cohorts. The summarized SMD was 0.43, with a 95%CI of 0.15-0.7. The test for the overall effect was significant at P < 0.05. Another subgroup analysis of QRSs (Figure 3C) included 73 and 74 participants in the RS and SCC groups, respectively. Although the trend signified favorable results for the RS group, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups. The summarized SMD was 0.54, with a 95%CI that ranged from -0.17 to 1.25. The test for the overall effect did not yield a significant effect. This subgroup analysis, focusing on studies that were not purely descriptive, continued to show a statistically significant difference (SMD: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.15-0.7), which agreed with the overall finding. This observation supports the potential impact of the RS combination on seizure duration, even after excluding certain study types. Nonetheless, despite a trend favoring the RS group, a statistically significant difference between two cohorts was not observed in the subgroup analysis focusing on randomized studies, which generally provide higher levels of evidence. The wider CI (-0.17 to 1.25) included zero, indicating that the observed effects could be attributed to chance. Preliminary data suggest that rocuronium, when reversed with sugammadex, maintains equivalent seizure duration compared to SCC. The difference in findings between the overall analysis and this specific subgroup (randomized studies) highlights the significance of the study design and warrants further investigations in the form of RCTs.

This meta-analysis evaluated recovery times in terms of spontaneous breathing resumption between the RS and SC groups across seven studies involving 398 observations (Figure 3D). One study did not reported data for recovery of respiration[15]. The pooled analysis found no statistically significant difference in recovery times (SMD: -0.51, 95%CI: -1.57 to 0.56, P = 0.2776), although the negative point estimate suggested a trend toward faster recovery with the administration of RS. Substantial heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 90.8%, P < 0.01), indicating significant variability in the study outcomes. The 3 studies showed significantly shorter recovery times with RS: Saricicek et al[13] (SMD: -1.99), Koksal et al[14] (SMD: -1.24), Karaca Bent et al[17] (SMD: -0.62). By contrast one study favored SCC (Moutaoukil et al[16], SMD: 0.96), and two showed neutral effects. Significant heterogeneity was detected (P < 0.01), implying inconsistent effects in the magnitude and/or direction among the studies. The I2 value demonstrated that 90.8% of the variability among the studies arose from heterogeneity rather than random chance. The τ2 was 0.928, τ was 0.965, and H was 3.33. The test of heterogeneity showed a Q value of 54.43 and P < 0.01.

Although the pooled analysis did not reveal a statistically significant difference in recovery times between RS and SCC (SMD: -0.52, 95%CI: -1.57 to 0.56, P = 0.278), the negative point estimate and the fact that 3 out of 7 studies favored RS indicated a potential trend towards faster recovery. However, substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 90.8%) prevented definitive conclusions. These findings should be interpreted with caution because of the inconsistent directional effects across studies and high variability in outcomes.

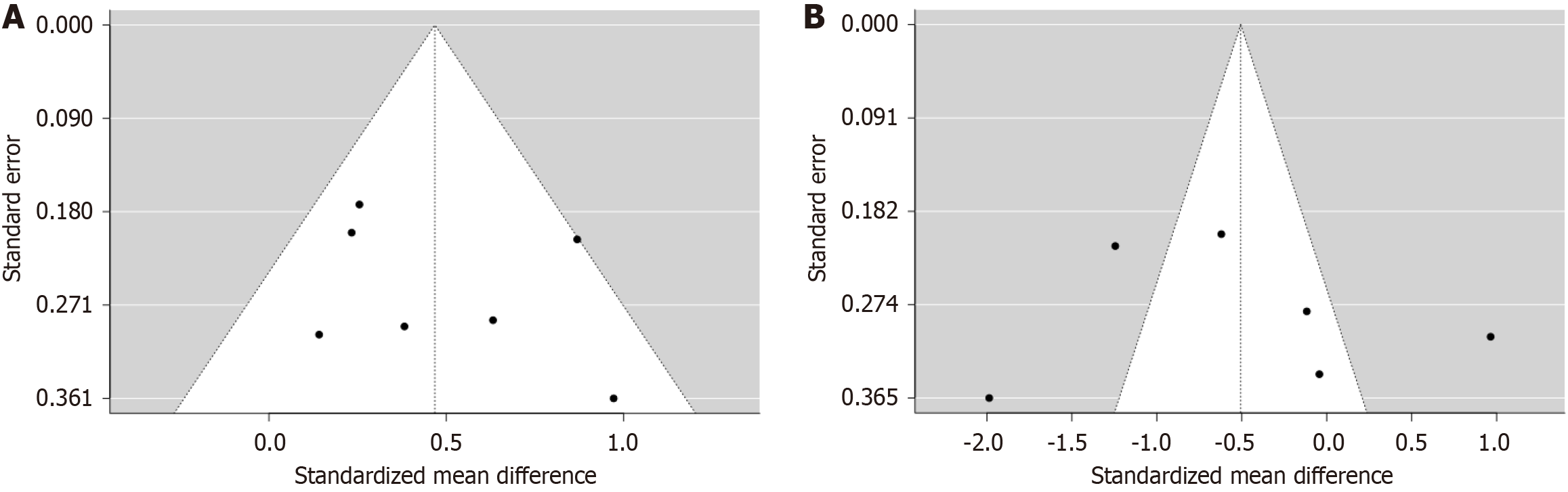

The funnel plot for both seizure duration and spontaneous breathing time did not indicate a potential publication bias. Egger’s test did not support the presence of funnel plot asymmetry (for seizure duration; intercept: 1.63, 95%CI: -2.48 to 5.75, t: 0.778, P value = 0.472; for spontaneous breathing time, (intercept: 2.75, 95%CI: -10.52 to 16.02, t: 0.406, P value = 0.705; Figure 4).

Thus, RS may facilitate more rapid recovery in specific clinical settings, definitive conclusions regarding its efficacy cannot be drawn owing to the high degree of heterogeneity. Institutional protocols and patient-specific factors must be considered while selecting an agent, particularly when the safety benefits of RS, such as the avoidance of SCC’s risks of hyperkalemia and malignant hyperthermia, may outweigh minor differences in recovery time. The primary conclusion from the analysis is that although the overall data suggest a longer seizure duration with RS, this effect is not observed in RCTs. In addition, the recovery time does not show a significant difference despite observable trends, all of which are influenced by considerable heterogeneity. Further research using standardized protocols is necessary to confirm these findings.

ECT is a procedure in which small electrical currents are applied through the skin to the brain, inducing generalized seizures to treat specific psychiatric disorders. Since its introduction, the scenarios in which ECT is an effective treatment have greatly expanded[6]. Neuromuscular blockers are often administered during seizures to minimize convulsive motor activity, thereby alleviating the risk of physical injuries, such as fractures[6]. These agents induce muscle relaxation during seizures, ensuring patient safety while undergoing ECT. The optimal dose aims to avoid prolonged paralysis, which can unnecessarily delay recovery[18]. These agents induce muscle relaxation, which is crucial in clinical settings, especially when controlling the physical manifestations of seizures. A systematic review of neuromuscular blocking agents for ECT observed that non-depolarizing agents, such as rocuronium, are preferred in patients with certain comorbidities[6]. However, neuromuscular blockade must be carefully monitored and pharmacologically reversed before emergence from anesthesia to ensure patient safety during ECT owing to the prolonged duration of action. RS is increasingly being considered a viable alternative to SCC for muscle relaxation during ECT[7]. RS provides a rapid onset of action and comparable recovery, making it suitable for ECT, where a quick and effective neuromuscular blockade is required, similar to SCC[19]. This combination is considered safe for use in special populations, including pregnant women and patients allergic to SCC[20].

This meta-analysis aimed to provide the most updated synthesis incorporating quantitative analysis to compare RS with SCC for neuromuscular blockade during ECT. The findings revealed several clinically important insights that warrant careful consideration. The most prominent finding was the significant increase in seizure duration in the case with RS compared to SCC (SMD: 0.43, 95%CI: 0.15-0.70). This effect persisted even after excluding descriptive studies, suggesting the biological plausibility of these results. However, the lack of statistical significance in the subgroup analysis of QRSs suggests the need for further confirmation. The prolongation of seizure duration in ECT following the administration of RS as opposed to SCC, may be attributed to the timing of electrical stimulation in relation to propofol administration; however, the precise mechanism yet to be elucidated[15]. Nevertheless, this finding should be cautiously interpreted as it was not replicated in the subgroup analysis of randomized studies, possibly due to the limited power from smaller sample sizes in the randomized designs. The seizure duration is traditionally regarded as a crucial determinant of the efficacy of ECT, with durations of 30 seconds to 60 seconds considered optimal for ECT[21,22]. This finding has key clinical implications. In case of recovery times, the pooled analysis did not indicate statistically significant difference (SMD: -0.51, 95%CI: -1.57 to 0.56, P = 0.277); nonetheless, the direction of the effect consistently favored RS in most studies. The substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) suggests that institutional protocols and dosing regimens critically influence recovery profiles. Studies employing higher sugammadex doses (≥ 4 mg/kg) demonstrated more rapid recovery, aligning with pharmacokinetic principles that optimal reversal requires adequate doses of neuromuscular blocker reversal.

The safety profile emerging from our analysis presents a compelling case for the use of RS. Although quantitative synthesis was limited by inconsistent reporting, qualitative assessment revealed fewer instances of myalgia, hyper

The comparative analysis of RS for rapid sequence induction intubation has been extensively investigated, with particular emphasis on intubation conditions, recovery times, and safety profiles[23]. SCC is traditionally preferred because of its rapid onset and short duration of action; rocuronium, especially when used in conjunction with suga

This study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the high heterogeneity, although addressed via random-effects models and subgroup analyses, means that the findings may not be generalizable across all clinical settings. Second, differences in the ECT technique (electrode placement and stimulus parameters) and anesthesia protocols (induction agents and monitoring standards) could have influenced the outcomes. Third, although funnel plots and Egger’s tests indicated the absence of significant asymmetries the predominance of small studies increases susceptibility to publication bias. Fourth, including all ECT sessions as independent data points might have introduced within-patient correlations not entirely addressed by random-effects models and the use of SMD, potentially overestimating the sample size or underestimating the variance. While this approach maximized the available data, this limitation should be considered when interpreting the pooled results.

The findings from this meta-analysis have key clinical implications. For patients at risk of SCC complications (e.g., those with neuromuscular disorders or hyperkalemia), RS appears to be a safe alternative that does not compromise seizure quality. The trend toward faster recovery, particularly with adequate sugammadex dosing, may enhance throughput in busy ECT suites. However, the specific context should be considered when implementing this approach as the learning curve for sugammadex use and cost implications are some of the practical challenges to be overcome.

Future research should prioritize large multicenter RCTs with standardized protocols to validate these findings. Dose-response relationships, long-term cognitive outcomes, and cost-effectiveness analyses warrant special attention. Furthermore, studies examining the impact of RS on ECT efficacy (e.g., remission rates) would provide beneficial clinical insights.

This meta-analysis indicates that the RS combination is a viable and safe alternative to SCC for muscle relaxation during ECT. In the overall analysis RS is associated with a longer seizure duration than SCC. It did not achieve statistical significance in the subgroup analysis of RCTs. Therefore, larger, high-quality RCTs are needed to definitively ascertain its impact on seizure quality. The pooled analysis did not identify statistically significant difference in recovery time between the two agents. However, a consistent trend favoring faster recovery with RS was observed across most studies, with considerable improvements in recovery profiles in studies employing higher sugammadex doses. This potential for expedited recovery, the qualitative observation of fewer adverse events, such as myalgia, and the avoidance of SCC’s risks (e.g., hyperkalemia and malignant hyperthermia), present a compelling safety advantage for RS. Despite substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, particularly in terms of recovery outcomes, RS emerges as a valuable option for patients undergoing ECT. Those with contraindications to SCC and those for whom a more predictable and controlled recovery is desired are likely to benefit from this approach. Nonetheless, further large-scale, methodologically rigorous RCTs with standardized protocols are warranted to confirm these findings, explore dose- response relationships, and assess long-term cognitive and cost-effectiveness outcomes in the context of ECT.

| 1. | Jaffe R. The Practice of Electroconvulsive Therapy: Recommendations for Treatment, Training, and Privileging: A Task Force Report of the American Psychiatric Association, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:331-331. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | de Mangoux GC, Amad A, Quilès C, Schürhoff F, Pignon B. History of ECT in Schizophrenia: From Discovery to Current Use. Schizophr Bull Open. 2022;3:sgac053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Payne NA, Prudic J. Electroconvulsive therapy: Part I. A perspective on the evolution and current practice of ECT. J Psychiatr Pract. 2009;15:346-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bahji A. The Rise, Fall, and Resurgence of Electroconvulsive Therapy. J Psychiatr Pract. 2022;28:440-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yang HS, Joung KW. Electroconvulsive therapy and muscle relaxants. Anesth Pain Med (Seoul). 2023;18:447-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mirzakhani H, Welch CA, Eikermann M, Nozari A. Neuromuscular blocking agents for electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2012;56:3-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Arora V, Henson L, Kataria S. Current evidence on the use of sugammadex for neuromuscular blockade antagonism during electroconvulsive therapy: a narrative review. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2025;78:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sacan O, White PF, Tufanogullari B, Klein K. Sugammadex reversal of rocuronium-induced neuromuscular blockade: a comparison with neostigmine-glycopyrrolate and edrophonium-atropine. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:569-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M, Griffiths F, Nicolau B, O’cathain A, Rousseau M, Vedel I, Pluye P. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. EFI. 2018;34:285-291. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in RCA: 1651] [Article Influence: 206.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fekete JT, Győrffy B. MetaAnalysisOnline.com: Web-Based Tool for the Rapid Meta-Analysis of Clinical and Epidemiological Studies. J Med Internet Res. 2025;27:e64016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 77.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hoshi H, Kadoi Y, Kamiyama J, Nishida A, Saito H, Taguchi M, Saito S. Use of rocuronium-sugammadex, an alternative to succinylcholine, as a muscle relaxant during electroconvulsive therapy. J Anesth. 2011;25:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kadoi Y, Hoshi H, Nishida A, Saito S. Comparison of recovery times from rocuronium-induced muscle relaxation after reversal with three different doses of sugammadex and succinylcholine during electroconvulsive therapy. J Anesth. 2011;25:855-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saricicek V, Sahin L, Bulbul F, Ucar S, Sahin M. Does rocuronium-sugammadex reduce myalgia and headache after electroconvulsive therapy in patients with major depression? J ECT. 2014;30:30-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koksal E, stun Y, Kaya C, Sahin A, Sahinoglu A. Comparing the effects of rocuronium-sugammadex and succinylcholine on recovery during electroconvulsive therapy. Anadolu Psikiyatri Derg. 2015;16:198. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Oflezer C, Atay Ö, Kaşdoğan ZE, Özakay G, İpekçioğlu D, Bahadır H. Does the Use of Rocuronium-Sugammadex Instead of Succinylcholine in Electroconvulsive Therapy Affect Seizure Duration? Psychiatry Investig. 2022;19:824-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moutaoukil MD, Najout H, Elkoundi A, Bensghir M. Comparison of Rocuronium-Sugammadex and Succinylcholine during Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Small Observational Case Series Study. Austin J Anesthesia Analgesia. 2022;10:1107. |

| 17. | Karaca Bent İ, Köşlük Gürler H, Ekinci O. A comparison of the effects of succinylcholine and rocuronium on recovery time from anesthesia and vital signs in electroconvulsive therapy. Intercont J Emerg Med. 2024;2:1-5. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Mirzakhani H, Guchelaar HJ, Welch CA, Cusin C, Doran ME, MacDonald TO, Bittner EA, Eikermann M, Nozari A. Minimum Effective Doses of Succinylcholine and Rocuronium During Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Prospective, Randomized, Crossover Trial. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:587-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hardman BL, Anand K, Joshi GP. Rapid Onset of Neuromuscular Blockade: Rocuronium vs. Succinylcholine- Neither Are Perfect! ASA Monit. 2022;86:42-42. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Karahan MA, Büyükfırat E, Binici O, Uyanıkoğlu H, Incebıyık A, Asoğlu M, Altay N. The Effects of Rocuronium-sugammadex on Fetomaternal Outcomes in Pregnancy Undergoing Electroconvulsive Therapy: A Retrospective Case Series and Literature Review. Cureus. 2019;11:e4820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Messer B, Wilkes J. The use of rocuronium and sugammadex in a patient with a history of suxamethonium allergy. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lalla FR, Milroy T. The current status of seizure duration in the practice of electroconvulsive therapy. Can J Psychiatry. 1996;41:299-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tran DT, Newton EK, Mount VA, Lee JS, Wells GA, Perry JJ. Rocuronium versus succinylcholine for rapid sequence induction intubation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD002788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Karcioglu O, Arnold J, Topacoglu H, Ozucelik DN, Kiran S, Sonmez N. Succinylcholine or rocuronium? A meta-analysis of the effects on intubation conditions. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:1638-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Soto R, Jahr JS, Pavlin J, Sabo D, Philip BK, Egan TD, Rowe E, de Bie J, Woo T. Safety and Efficacy of Rocuronium With Sugammadex Reversal Versus Succinylcholine in Outpatient Surgery-A Multicenter, Randomized, Safety Assessor-Blinded Trial. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e1654-e1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Aragón-Benedí C, Visiedo-Sánchez S, Pascual-Bellosta A, Ortega-Lucea S, Fernández-Liesa R, Martínez-Ubieto J; Research Group in Anesthesia, Resuscitation AND Perioperative Medicine of Aragón Health Research Institute (IIS Aragón). Study of Rocuronium-Sugammadex as an Alternative to Succinylcholine-Cisatracurium in Microlaryngeal Surgery. Laryngoscope. 2021;131:E212-E218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/