Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112235

Revised: August 11, 2025

Accepted: November 14, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 192 Days and 22.4 Hours

While several studies have explored the relationship among physical activity (PA), depressive symptoms, and cognitive health, the distinct effects of PA per

To investigate the differential impacts of job-related vs leisure-related physical activities on depressive symptoms and cognitive function among adults aged 45 years and older in China.

Data were extracted from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, encompassing 16476 participants. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, and cognitive func

Vigorous-intensity PA for job demands (JVPA) was significantly associated with increased depressive symptoms [P = 0.011, odds ratio (OR) = 1.003], indicating that high-intensity job-related activities may exacerbate mental health issues. Moderate-intensity PA for entertainment or exercise (EMPA) was inversely associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.030, OR = 0.999), suggesting that moderate-intensity leisure activities can reduce depressive symptoms. For cognitive function, the total PA for job demands was correlated with cognitive decline (P = 0.004, OR = 1.008), with the frequency of JVPA showing a positive association. However, EMPA was linked to reduced cognitive decline

JVPA exacerbates depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment, whereas EMPA mitigates depression and supports cognitive health. Targeted interventions promoting leisure-related PA may enhance mental and cognitive well-being in older adults.

Core Tip: This study investigates the differential impacts of job-related vs leisure-related physical activities (PA) on depressive symptoms and cognitive function among middle-aged and elderly adults in China, using data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Key findings indicate that vigorous-intensity PA for job demands exacerbates depressive symptoms and cognitive decline, while moderate-intensity PA for entertainment reduces depressive symptoms and supports cognitive health. These results highlight the importance of promoting leisure-based PA to enhance mental well-being and cognitive outcomes in aging populations, suggesting targeted interventions could be beneficial.

- Citation: Zhao QR, Xie L, Li B, Zhao XY, Yang SN, Yang Y, Dong L, Wang Q. Differential impacts of job-related vs leisure-related physical activity on depressive and cognitive function among middle-aged and elderly adults. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 112235

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/112235.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112235

As the global population continues to age, understanding the complex effects of physical activity (PA) on mental and cognitive health in older adults has become increasingly important. This issue is particularly relevant in China, which has the largest elderly population in the world. As of 2023, over 21.1% (296.97 million) of individuals are aged 60 years and above according to the “National Ageing Development Bulletin” published by the National Health Commission of China[1,2].

Aging is often accompanied by an increased prevalence of depressive symptoms and cognitive decline, both of which significantly diminish quality of life and impose substantial economic burdens on healthcare systems[3]. Identifying modifiable lifestyle factors such as PA that can mitigate these conditions is of primary relevance for public health. PA has long been recognized as a key determinant of physical, mental, and cognitive health[4,5]. It plays a protective role against several brain age-related conditions, including cognitive decline, neurodegenerative disorders, and overall brain function deterioration[6,7]. Evidence suggests that PA can alleviate depressive symptoms through mechanisms such as improved neuroplasticity, enhanced serotonin utilization, and reductions in systemic inflammation[8]. For cognitive health, PA promotes neurogenesis, increases hippocampal volume, and reduces β-amyloid deposition, thereby mitigating the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia[9].

Despite the wealth of research on PA and its health benefits in elderly populations, much of the existing literature treats PA as a homogeneous construct, failing to differentiate between its various types and purposes. PA for job demands (JPA), often characterized by necessity and high physical demands, may not confer the same benefits as PA for entertainment or exercise (EPA), which is typically voluntary and associated with relaxation and social interaction[10,11]. JPA may even exacerbate stress and depressive symptoms due to its obligatory nature, lack of autonomy, and potential physical strain[11]. Meanwhile, EPA may positively influence mental and cognitive health through its association with psychological well-being and social engagement[12]. However, studies have not systematically explored these dis

This study aims to address these gaps by examining the differential impacts of job-related vs leisure-related physical activities on depressive symptoms and cognitive function among Chinese adults aged 45 and older. Using data from the nationally representative China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), we categorize PA by purpose (job vs leisure) and intensity (vigorous, moderate, low) to explore their associations with mental and cognitive health. While previous studies have focused on general physical activity levels[1,13], to our knowledge, this research is among the first to explore the distinct effects of job-related and leisure-related PA in a large aging population. Our findings highlight the importance of promoting leisure-based PAs for enhancing mental and cognitive health, providing actionable insights for policymakers and healthcare practitioners in designing effective, culturally tailored interventions.

The data for this study were obtained from the 2018 CHARLS, which is a longitudinal survey designed to be representative of individuals aged 45 years and older residing in mainland China, covering the period of 2011-2018. This comprehensive dataset encompasses a wide array of information, including socioeconomic status and health conditions, thereby supporting scientific research focused on middle-aged and elderly populations.

All data collected during CHARLS are housed within the CHARLS database at Peking University, China. CHARLS was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (No. IRB00001052-11015). Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their inclusion in the study. The CHARLS team removed direct identifiers prior to data release to ensure participant confidentiality, retaining only anonymized participant IDs for cross-period tracking and matching, thereby preventing any potential tracing back to individuals. Further details regarding CHARLS can be accessed on the official website: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/en/.

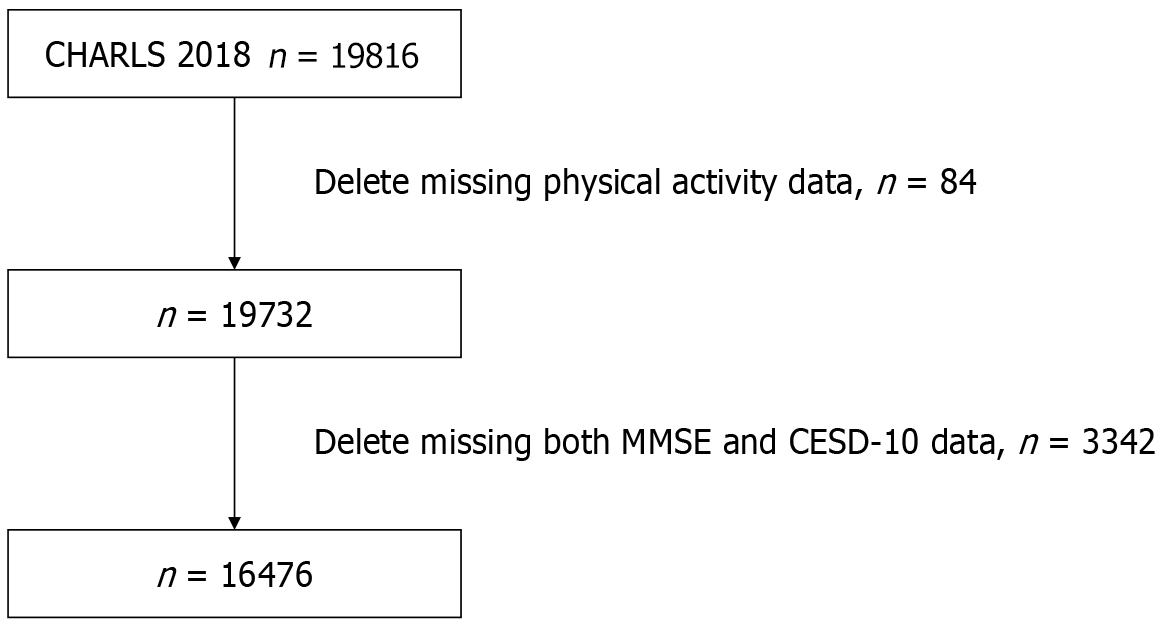

In alignment with the objectives of this study, specific exclusion criteria for participant selection were established, which included the absence of data from the 10-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CESD-10) questionnaire and cognitive-related assessments. Consequently, a total of 16476 subjects were selected from an initial pool of 19816 participants. Figure 1 presents the flowchart detailing the data selection process.

Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms were measured by the summary score from the validated Chinese version of CESD-10 (score: 0-30). A threshold of 12 indicated possible clinical depression[14].

Cognitive function: Cognitive functions were measured by the summary score from the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE; score: 0-30), including simple tasks in several areas: The test of time and place, the repeating lists of words, arithmetic such as serial subtractions of seven, language use and comprehension, and basic motor skills[15]. A threshold of 20 indicated possible moderate or severe cognitive decline.

PA: The level of PA was assessed by measuring different parameters.

Purpose: Participants were asked about the purpose of PA. The answers were classified into two types: (1) JPA; and (2) EPA.

Intensity: PA was classified into three intensity levels: (1) Vigorous-intensity activity (VPA) refers to activities that can cause shortness of breath (e.g., carrying heavy stuff, digging, hoeing, aerobic workout, bicycling at a fast speed, and riding a cargo bike/motorcycle); (2) Moderate-intensity activity (MPA) refers to activities that can make participants’ breathe faster than usual (e.g., carrying light stuff, bicycling at a normal speed, mopping, Tai-Chi, and speed walking); and (3) Low-intensity activity (LPA) refers to activities such as walking. Specifically, JPA was classified into vigorous-intensity JPAs (JVPA), moderate-intensity JPAs (JMPA), and low-intensity intensity JPAs (JLPA). Likewise, EPA was classified into vigorous-intensity EPA (EVPA), moderate-intensity EPA (EMPA) and low-intensity intensity EPA (ELPA).

Frequency: Participants were asked how many days a week they participated in VPA/MPA/LPA for at least 10 minutes. The responses ranged from 0 day to 7 days per week.

Duration Participants were asked how long they do VPA/MPA/LPA every day. The responses included no activity over 10 minutes/day, 10-29 minutes/days, 30-119 minutes/day, 120-239 minutes/day, and ≥ 240 minutes/day. The duration was recorded as 5 minutes/day, 20 minutes/day, 75 minutes/day, 180 minutes/days, and 240 minutes/day separately to calculate the scores of total JPAs (JTPA) and total EPA (ETPA)[16].

JTPA and ETPA scores: The amount of PA was calculated by multiplying frequency by the duration of each PA intensity. Instead of hours per day, the JTPA and ETPA scores were measured in metabolic equivalent (MET) hours per day (hour/day) by using a structured validated questionnaire. According to previous studies[17], 1 MET refers to oxygen con

Covariates: The covariates were screened based on basic individual information, including gender, age, residence education, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and sleep duration.

A retrospective clinical case review of 200 adults aged 45 years and older who visited the Department of Geriatrics at our hospital between January 2020 and December 2024 was conducted to further validate the findings from the CHARLS dataset. The inclusion criteria for these cases included the following: (1) Age ≥ 45 years; (2) Availability of complete medical records, including depressive symptoms and cognitive function assessments; and (3) Documented PA levels categorized as job-related or leisure-related.

Data were collected through a structured review of electronic medical records. Depressive symptoms were assessed using the CESD-10 questionnaire, and cognitive function was evaluated using MMSE. PA data were extracted from patient histories, detailing the purpose (job-related vs leisure-related), intensity (vigorous, moderate, low), frequency, and duration of activities. For each participant, the JTPA and ETPA scores were calculated using the same MET-based formula described in the “Covariates” section. Covariates, such as gender, age, educational level, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and sleep duration, were recorded. This additional dataset aims to provide clinical validation and support the generalizability of the findings from the CHARLS database. The study received approval from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of our hospital. Given the use of anonymized patient data with no potential for harm, informed consent was waived in accordance with the ethical guidelines for retrospective research.

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD and categorical variables as the frequency and percentage. Mul

The cross-sectional study included 16476 participants. Among them, 48.1% were male, 55.9% were under 60 years old, 78.7% resided in urban areas, 62.9% had at most a primary school education, 87.2% were married, 42.4% had a smoking history, and 37.5% had a drinking history. The sleep duration was 6.227 ± 1.912, and the nap duration was 40.273 ± 48.302 minutes (Table 1).

| Variables | Value (n = 16476) |

| Male | 7929 (48.1) |

| Age < 60 years | 9210 (55.9) |

| Rural residence | 12962 (78.7) |

| Education level | |

| Primary school or below | 10366 (62.9) |

| Middle school or above | 6110 (37.1) |

| Married | 14363 (87.2) |

| Smoking | 6989 (42.4) |

| Drinking | 4539 (37.5) |

| Sleep duration, hours | 6.227 ± 1.912 |

| Nap duration, minutes | 40.273 ± 48.302 |

Among the participants, 4.7% experienced adverse health events, and 42.8% reported having no comorbidities. Most participants (98.3%) were independent in their daily activities, and 88.2% reported that their health did not influence their daily life. Self-perceptions varied, with 55.3% rating their health as good, and financial perceptions showed that 78.5% considered their income moderate (Table 2).

| Variables | Value (n = 16476) |

| Adverse health events | 774 (4.7) |

| Reported comorbidity | |

| 0 | 7068 (42.8) |

| 1 | 6179 (37.5) |

| 2 | 2323 (14.2) |

| ≥ 3 | 906 (5.5) |

| Activities of daily living | |

| Independent | 16196 (98.3) |

| Dependent | 280 (1.7) |

| Whether health influence life | |

| Yes | 1927 (11.8) |

| No | 14549 (88.2) |

| Self-perceived health | |

| Poor | 1154 (7.0) |

| Moderate | 6211 (37.7) |

| Good | 9111 (55.3) |

| Self-perceived income | |

| Poor | 1944 (11.8) |

| Moderate | 12933 (78.5) |

| Rich | 1599 (9.7) |

The average score for “everything was an effort” was notably higher at 1.95 ± 0.20, indicating the prevalence of this symptom, whereas restless sleep and trouble concentrating scored 1.55 ± 0.41 and 1.63 ± 0.39, respectively. Participants reported feeling bothered by things (1.59 ± 0.38) and depressed (1.61 ± 0.42) with moderate frequency. Lower frequencies were noted for feeling fearful (1.27 ± 0.36) and hopeless about the future (0.98 ± 0.32), with the lowest score observed for the inability to “get going” (0.95 ± 0.21). Notably, participants reported feeling lonely, with an average score of 1.45 ± 0.58, but maintained a moderate level of happiness (1.48 ± 0.25) (Table 3).

| Variables | Value (n = 16476) |

| Everything was an effort | 1.95 ± 0.20 |

| Restless sleep | 1.55 ± 0.41 |

| Trouble concentrating | 1.63 ± 0.39 |

| Bothered by things | 1.59 ± 0.38 |

| Depressed | 1.61 ± 0.42 |

| Fearful | 1.27 ± 0.36 |

| Lonely | 1.45 ± 0.58 |

| Happy | 1.48 ± 0.25 |

| Could not “get going” | 0.95 ± 0.21 |

| Hopeful about future | 0.98 ± 0.32 |

The mean total cognitive function score was 25.41 ± 2.39, indicating a generally preserved cognitive status among participants. The scores across specific domains revealed varied cognitive abilities, with orientation (to time and place) scoring 4.46 ± 0.55 and registration at 2.31 ± 0.49. The performance in attention and calculation was moderate, with a mean score of 3.28 ± 0.95, and recall ability scored at 2.32 ± 0.89. Language competence was reflected by a score of 1.89 ± 0.29. Repetition and complex commands had lower mean scores of 0.95 ± 0.46 and 1.55 ± 1.35, respectively, suggesting these areas may involve higher cognitive demands (Table 4).

| Variables | Value (n = 16476) |

| Total score | 25.41 ± 2.39 |

| Orientation (to time, to place) | 4.46 ± 0.55 |

| Registration | 2.31 ± 0.49 |

| Attention and calculation | 3.28 ± 0.95 |

| Recall | 2.32 ± 0.89 |

| Language | 1.89 ± 0.29 |

| Repetition | 0.95 ± 0.46 |

| Complex commands | 1.55 ± 1.35 |

Multivariate regression analysis (model 1) revealed that JTPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms [P = 0.011, odds ratio (OR) = 1.003, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.001-1.005]. Specifically, the frequency and duration per session of JVPA showed significant associations with depressive symptoms (frequency: P = 0.022, OR = 1.017, 95%CI: 1.002-1.031; duration: P = 0.005, OR = 1.001, 95%CI: 1.000-1.001) in Table 5. ETPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.011, OR = 1.003, 95%CI: 1.001-1.005), with the duration per session of EMPA showing a significant association (P = 0.030, OR = 0.999, 95%CI: 0.998-1.000). Other PA variables, including frequency and duration of JMPA, JLPA, ELPA, and EVPA and frequency of EMPA, did not demonstrate statistically significant associations with depressive symptoms.

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.011a | 1.003 | 1.001-1.005 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.022a | 1.017 | 1.002-1.031 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.619 | 1.003 | 0.990-1.017 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.768 | 1.002 | 0.990-1.014 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.005b | 1.001 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.164 | 1.000 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.782 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.000 |

| ETPA score | 0.011a | 1.003 | 1.001-1.005 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.797 | 1.005 | 0.970-1.040 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.109 | 0.964 | 0.921,1.008 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.718 | 10.992 | 0.951-1.035 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.291 | 1.001 | 0.999-1.002 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.030a | 0.999 | 0.998-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.064 | 0.999 | 0.999-1.000 |

In model 2, JTPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.012, OR = 1.003, 95%CI: 1.001-1.005), as was the frequency of JVPA, showing a significant positive association (P = 0.012, OR = 1.003, 95%CI: 1.001-1.005) in Table 6. Additionally, the duration per session of JVPA was significantly related to depressive symptoms (P = 0.005, OR = 1.001, 95%CI: 1.000-1.001). ETPA was inversely associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.022, OR = 0.992, 95%CI: 0.985-0.999), with EMPA displaying a significant inverse correlation (P = 0.031, OR = 0.999, 95%CI: 0.998-1.000). Other variables, including the frequency and duration of JMPA, JLPA, EVPA, and ELPA and frequency of EMPA, did not show statistically significant associations, suggesting these activities may not be independently influential on depressive symptoms in this cohort.

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.012a | 1.003 | 1.001-1.005 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.012a | 1.003 | 1.001-1.005 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.629 | 1.003 | 0.990-1.017 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.782 | 1.002 | 0.990-1.014 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.005b | 1.001 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.168 | 1.000 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.778 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.000 |

| ETPA score | 0.022a | 0.992 | 0.985-0.999 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.795 | 1.005 | 0.970-1.040 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.109 | 0.964 | 0.921-0.008 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.721 | 0.992 | 0.951-1.035 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.290 | 1.001 | 0.999-1.002 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.031a | 0.999 | 0.998-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.670 | 0.999 | 0.999-1.000 |

In this investigation of cognitive function and its association with PA among middle-aged and elderly adults in CHARLS, the multivariate regression analyses (models 1 and 2) highlighted key findings (Tables 7 and 8). JTPA was consistently correlated with cognitive decline (model 1: P = 0.004, OR = 1.008, 95%CI: 1.002-1.007; model 2: P = 0.003, OR = 1.007, 95%CI: 1.002-1.011). The frequency of JVPA showed significant positive associations with cognitive decline in both models (model 1: P = 0.001, OR = 1.046, 95%CI: 1.018-1.075; model 2: P = 0.023, OR = 1.017, 95%CI: 1.002-1.031). Though the duration of JVPA was not statistically significant, the EMPA duration per time illustrated a consistent inverse relationship with cognitive decline in both models (model 1: P = 0.017, OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.996-1.000; model 2: P = 0.018, OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.996-1.000). Other PA variables, including the frequency and duration of JMPA, JLPA, EVPA, and ELPA and frequency of EMPA, did not demonstrate statistically significant associations, suggesting that these activities may not be as influential on cognitive outcomes in this cohort.

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.004b | 1.008 | 1.002-1.007 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.001b | 1.046 | 1.018-1.075 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.210 | 0.984 | 0.959-1.009 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.990 | 1.000 | 0.978-1.022 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.107 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.693 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.315 | 1.000 | 1.000-1.001 |

| ETPA score | 0.358 | 0.996 | 0.984-1.006 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.397 | 1.025 | 0.968-1.085 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.158 | 0.949 | 0.882-1.021 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.870 | 0.994 | 0.927-1.067 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.071 | 1.002 | 1.000-1.004 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.017a | 0.998 | 0.996-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.732 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.003b | 1.007 | 1.002-1.011 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.023a | 1.017 | 1.002-1.031 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.629 | 1.003 | 0.990-1.017 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.782 | 1.002 | 0.990-1.014 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.105 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.712 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.315 | 1.000 | 1.000-1.001 |

| ETPA score | 0.357 | 0.995 | 0.984-1.006 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.795 | 1.005 | 0.970-1.040 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.109 | 0.964 | 0.921-0.008 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.721 | 0.992 | 0.951-1.035 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.068 | 1.002 | 1.000-1.004 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.018a | 0.998 | 0.996-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.709 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

The retrospective clinical study included 200 clinical participants. Among them, 49.0% were male, 52.5% were under 60 years old, 78.5% resided in rural areas, 63.0% had at most a primary school education, 87.0% were married, 42.5% had a smoking history, and 37.5% had a drinking history. The sleep duration was 6.251 ± 1.873 hours, and the nap duration was 40.306 ± 44.532 minutes (Table 9). Among the clinical participants, 4.5% experienced adverse health events, and 45.0% reported having no comorbidities. Most participants (98.5%) were independent in their daily activities, and 88.0% reported that their health did not influence their daily life. Self-perceptions varied, with 56.0% rating their health as good, and financial perceptions showed that 78.5% considered their income moderate (Table 10).

| Variables | Value (n = 200) |

| Male | 98 (49.0) |

| Age < 60 years | 105 (52.5) |

| Rural residence | 157 (78.5) |

| Education level | |

| Primary school or below | 126 (63.0) |

| Middle school or above | 74 (37.0) |

| Married | 174 (87.0) |

| Smoking | 85 (42.5) |

| Drinking | 75 (37.5) |

| Sleep duration, hour | 6.251 ± 1.873 |

| Nap duration, minute | 40.306 ± 44.532 |

| Variables | Value (n = 200) |

| Adverse health events | 9 (4.5) |

| Reported comorbidity | |

| 0 | 90 (45.0) |

| 1 | 75 (37.5) |

| 2 | 25 (12.5) |

| ≥ 3 | 10 (5.0) |

| Activities of daily living | |

| Independent | 197 (98.5) |

| Dependent | 3 (1.5) |

| Whether health influence life | |

| Yes | 24 (12.0) |

| No | 176 (88.0) |

| Self-perceived health | |

| Poor | 18 (9.0) |

| Moderate | 70 (35.0) |

| Good | 112 (56.0) |

| Self-perceived income | |

| Poor | 24 (12.0) |

| Moderate | 157 (78.5) |

| Rich | 19 (9.5) |

The average score for “everything was an effort” was notably higher at 1.91 ± 0.25, indicating the prevalence of this symptom, whereas restless sleep and trouble concentrating scored 1.54 ± 0.33 and 1.65 ± 0.35, respectively. Participants reported feeling bothered by things (1.54 ± 0.41) and depressed (1.67 ± 0.46) with moderate frequency. Lower frequencies were noted for feeling fearful (1.23 ± 0.34) and hopeless about the future (0.94 ± 0.29), with the lowest score observed for the inability to ‘get going’ (0.97 ± 0.27). Notably, participants reported feeling lonely, with an average score of 1.40 ± 0.52, but maintained a moderate level of happiness (1.45 ± 0.31) (Table 11).

| Variables | Value (n = 200) |

| Everything was an effort | 1.91 ± 0.25 |

| Restless sleep | 1.54 ± 0.33 |

| Trouble concentrating | 1.65 ± 0.35 |

| Bothered by things | 1.54 ± 0.41 |

| Depressed | 1.67 ± 0.46 |

| Fearful | 1.23 ± 0.34 |

| Lonely | 1.40 ± 0.52 |

| Happy | 1.45 ± 0.31 |

| Could not “get going” | 0.97 ± 0.27 |

| Hopeful about future | 0.94 ± 0.29 |

The mean total cognitive function score was 25.47 ± 2.11, indicating a generally preserved cognitive status among participants. The scores across specific domains revealed varied cognitive abilities, with orientation (to time and place) scoring 4.26 ± 0.56 and registration at 2.23 ± 0.43. The performance in attention and calculation was moderate, with a mean score of 3.19 ± 0.74, and recall ability scored at 2.24 ± 0.79. Language competence was reflected by a score of 1.96 ± 0.32. Repetition and complex commands had lower mean scores of 0.92 ± 0.45 and 1.68 ± 1.56, respectively, suggesting that these areas may involve higher cognitive demands (Table 12).

| Variables | Value (n = 200) |

| Total score | 25.47 ± 2.11 |

| Orientation (to time, to place) | 4.26 ± 0.56 |

| Registration | 2.23 ± 0.43 |

| Attention and calculation | 3.19 ± 0.74 |

| Recall | 2.24 ± 0.79 |

| Language | 1.96 ± 0.32 |

| Repetition | 0.92 ± 0.45 |

| Complex commands | 1.68 ± 1.56 |

Multivariate regression analysis (external validation) revealed that JTPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.020, OR = 1.004, 95%CI: 1.001-1.007). Specifically, the frequency and duration per session of JVPA showed significant associations with depressive symptoms (frequency: P = 0.030, OR = 1.015, 95%CI: 1.001-1.029; duration: P = 0.008, OR = 1.001, 95%CI: 1.000-1.002). ETPA was significantly associated with depressive symptoms (P = 0.015, OR = 1.004, 95%CI: 1.001-1.007), with the duration per session of EMPA showing a significant association (P = 0.040, OR = 0.999, 95%CI: 0.998-1.000). Other PA variables, including frequency and duration of JMPA, JLPA, ELPA, and EVPA and frequency of EMPA, did not demonstrate statistically significant associations with depressive symptoms (Table 13).

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.020a | 1.004 | 1.001-1.007 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.030a | 1.015 | 1.001-1.029 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.650 | 1.004 | 0.989-1.019 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.800 | 1.001 | 0.989-1.013 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.008b | 1.001 | 1.000-1.002 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.180 | 1.000 | 1.000-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.800 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| ETPA score | 0.015a | 1.004 | 1.001-1.007 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.800 | 1.006 | 0.968-1.045 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.120 | 0.960 | 0.915-1.007 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.750 | 1.000 | 0.955-1.047 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.300 | 1.001 | 0.999-1.003 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.040a | 0.999 | 0.998-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.080 | 0.999 | 0.999-1.000 |

JTPA was consistently correlated with cognitive decline (P = 0.005, OR = 1.007, 95%CI: 1.002-1.012). The frequency of JVPA showed significant positive associations with cognitive decline (P = 0.002, OR = 1.040, 95%CI: 1.015-1.066). Though the duration of JVPA was not statistically significant, the EMPA duration per time illustrated a consistent inverse relationship with cognitive decline (P = 0.020, OR = 0.998, 95%CI: 0.996-1.000). Other PA variables, including frequency and duration of JMPA, JLPA, EVPA, and ELPA and frequency of EMPA, did not demonstrate statistically significant associations, suggesting that these activities may not be as influential on cognitive outcomes in this cohort (Table 14).

| Variables | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| JTPA score | 0.005b | 1.007 | 1.002-1.012 |

| JVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.002b | 1.040 | 1.015-1.066 |

| JMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.250 | 0.988 | 0.963-1.014 |

| JLPA frequency (day/week) | 0.995 | 1.000 | 0.977-1.023 |

| JVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.150 | 1.001 | 1.000-1.002 |

| JMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.720 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| JLPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.350 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

| ETPA score | 0.400 | 0.997 | 0.985-1.009 |

| EVPA frequency (day/week) | 0.450 | 1.020 | 0.960-1.084 |

| EMPA frequency (day/week) | 0.200 | 0.950 | 0.880-1.025 |

| ELPA frequency (day/week) | 0.900 | 0.995 | 0.925-1.070 |

| EVPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.100 | 1.002 | 1.000-1.004 |

| EMPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.020a | 0.998 | 0.996-1.000 |

| ELPA duration per time (minutes) | 0.750 | 1.000 | 0.999-1.001 |

In analyzing the effects of PA on depressive symptoms and cognitive function among middle-aged and elderly adults using data from CHARLS, this study provides novel insights that enhance the understanding of the nuanced roles that different types and intensities of PA play in mental health and cognitive resilience. The association between depressive symptoms and PA, particularly the differentiation between JPA and EPA, is a compelling aspect of the results. The positive correlation identified between JVPA and depressive symptoms contrasts with much of the existing literature that generally supports a buffering or alleviative effect of PA on depression[18,19]. This discrepancy could be attributed to the psychological and physical stress associated with PA performed out of necessity rather than choice[20]. Vigorous work-related activities may be perceived as less enjoyable and more physically draining, potentially exacerbating stress and fatigue, which could compound depressive symptoms, particularly in middle-aged and elderly adults who may have limited physical capacity to recover from high-intensity demands[21,22].

Meanwhile, EMPA was inversely associated with depressive symptoms, suggesting a potentially protective effect. This is aligned with the broader literature indicating that voluntary, leisure-based PA is more consistently associated with mental well-being[23]. EPA, especially when engaging in social elements, likely provides not only a physical outlet but also emotional and cognitive enrichments such as socialization, fulfillment, and stress reduction[24]. These findings support the notion of exercise as a multi-dimensional intervention in mental health, where the context and nature of the activity may importantly determine the outcome.

The analysis of the relationship between PA and cognitive function revealed that total PA and the frequency of JVPAs were positively associated with cognitive decline. These findings suggest a complex relationship where, while structured, regular vigorous PA can stimulate neurogenesis and enhance synaptic plasticity, the increased stress and fatigue associated with high-intensity job-related PA, particularly when performed under pressure or without sufficient recovery, could counteract these cognitive benefits and contribute to cognitive decline over time[25].

While EMPA showed associations suggesting reduced cognitive decline, the absence of statistically significant associations for other levels and types of PA warrants further discussion. Some forms of PA may only exert subtle influence over cognitive domains, insufficient to manifest in measurable improvements over short durations or in certain contexts[26,27]. In addition, individual differences in health status, cognitive baseline, and lifestyle factors like diet and education could modulate how, and to what extent, physical activities impact cognitive health, possibly masking or interacting with the observed effects within this cohort[28].

The role of lifestyle covariates, such as smoking, alcohol consumption, and sleep, further complicates these rela

Mechanistically, the role of biological pathways is worth considering, such as the anti-inflammatory effects of exercise, the modulation of neurotransmitter systems (e.g., increased release of endorphins, serotonin, and dopamine), and improvements in cardiovascular health that reduce the risk of comorbidities affecting mood and cognition[30]. Spe

Voluntary leisure-based PA offers additional psychological benefits, such as improved mood and reduced cognitive fatigue. The autonomy in choosing leisure activities enhances their holistic benefits, contributing to mental resilience beyond mere physiological exertion[32]. Given these insights, promoting leisure-based PA can serve as an effective intervention strategy for mental health and cognitive preservation in aging populations. Policymakers and health practitioners should consider individual preferences and contexts when designing PA programs, ensuring that they are accessible, enjoyable, and suitable for all participants.

While this study provides valuable insights into the relationship between different types of PA and their effects on depressive symptoms and cognitive function among middle-aged and elderly adults, several limitations must be acknowledged. The cross-sectional nature of the study restricts the ability to establish causal relationships because only associations at a single time point were observed. The observed associations do not necessarily imply causality. The reliance on self-reported data for PA and other lifestyle factors introduces the potential for recall bias and inaccuracies, which could affect the robustness of the findings. Cultural and socioeconomic factors unique to the Chinese population, such as traditional health beliefs and economic disparities, may influence PA levels and cognitive outcomes, potentially affecting the generalizability of the findings. While the results demonstrated statistical significance, the ORs (e.g., 1.003 and 0.999) suggest very small effect sizes, which may limit the clinical significance of these findings. The absence of data on the intensity or frequency of certain cognitive and lifestyle factors, which were not captured or controlled for, may confound the results. Furthermore, while the study adjusted for several covariates, other unmeasured confounding variables, such as dietary habits and genetic predispositions, may exist, which could influence the outcomes. Future studies could benefit from longitudinal designs with specific measures, such as repeated assessments over time and more comprehensive data collection, to better elucidate these complex relationships.

This study suggests that PA associated with job demands, particularly VPAs, may be linked to an increased risk of depression and moderate to severe cognitive decline in middle-aged and elderly adults. Conversely, moderate-intensity PA undertaken for recreational or exercise purposes appears to potentially confer protective effects against depression and cognitive decline in middle-aged and older populations. These findings suggest that distinguishing between the types of PA is important because job-related physical exertion may not serve as a substitute for engaging in leisure or exercise-oriented activities. Future research should explore whether these associations hold over time and investigate the mechanisms underlying these potential relationships. Additionally, targeted interventions aimed at promoting mental health through appropriate PA modalities could be explored.

The authors extend their heartfelt thanks to all participants of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study team for their dedication to the project. We are deeply appreciative of Peking University for their invaluable support in collecting, organizing, and providing access to the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study database, as well as the involvement of all individuals associated with this effort.

| 1. | Dong N, Yi X, Mao L, Wang B, Sharma M, Si L, Xie G, Xu X. Geographical distribution disparities and prediction of health satisfaction among middle-aged and elderly adults in China: An analysis based on national data. Ann Epidemiol. 2025;108:16-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu H, Wang Y, Zhang H, Yin X, Wang L, Wang L, Wu J. An investigation into the health status of the elderly population in China and the obstacles to achieving healthy aging. Sci Rep. 2024;14:31123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Munro CE, Boyle R, Chen X, Coughlan G, Gonzalez C, Jutten RJ, Martinez J, Orlovsky I, Robinson T, Weizenbaum E, Pluim CF, Quiroz-Gaviria YT, Gatchel JR, Vannini P, Amariglio R. Recent contributions to the field of subjective cognitive decline in aging: A literature review. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2023;15:e12475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liu J, Qiang F, Dang J, Chen Q. Depressive Symptoms as Mediator on the Link between Physical Activity and Cognitive Function: Longitudinal Evidence from Older Adults in China. Clin Gerontol. 2023;46:808-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Boa Sorte Silva NC, Barha CK, Erickson KI, Kramer AF, Liu-Ambrose T. Physical exercise, cognition, and brain health in aging. Trends Neurosci. 2024;47:402-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sujkowski A, Hong L, Wessells RJ, Todi SV. The protective role of exercise against age-related neurodegeneration. Ageing Res Rev. 2022;74:101543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hoogen H, Hebling Vieira B, Langer N. Maintaining Brain Health: The Impact of Physical Activity and Fitness on the Aging Brain-A UK Biobank Study. Eur J Neurosci. 2025;61:e70085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hossain MN, Lee J, Choi H, Kwak YS, Kim J. The impact of exercise on depression: how moving makes your brain and body feel better. Phys Act Nutr. 2024;28:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Santiago JA, Quinn JP, Potashkin JA. Physical Activity Rewires the Human Brain against Neurodegeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Koh YS, Asharani PV, Devi F, Roystonn K, Wang P, Abdin E, Sum CF, Lee ES, Chong SA, Subramaniam M. Benefits of leisure-related physical activity and association between sedentary time and risk for hypertension and type 2 diabetes. Ann Acad Med Singap. 2023;52:172-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li J, Yuan B, Lan J, Huang X. How Late-Life Working Affects Depression Among Retirement-Aged Workers? An Examination of the Influence Paths of Job-Related (Non-Job-Related) Physical Activity and Social Contact. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64:e435-e442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Feng C, Shi Z, Tian Y, Ma C, Sun Q. Longitudinal associations between leisure activities and subjective happiness among middle-aged and older adults people in China: national cohort study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1441703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li X, Wang P, Jiang Y, Yang Y, Wang F, Yan F, Li M, Peng W, Wang Y. Physical activity and health-related quality of life in older adults: depression as a mediator. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cheng ST, Chan AC. The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in older Chinese: thresholds for long and short forms. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20:465-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56757] [Cited by in RCA: 61825] [Article Influence: 1212.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kujala UM, Kaprio J, Sarna S, Koskenvuo M. Relationship of leisure-time physical activity and mortality: the Finnish twin cohort. JAMA. 1998;279:440-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lei XL, Gao K, Wang H, Chen W, Chen GR, Wen X. The role of physical activity on healthcare utilization in China. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:2378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Moroń M, Mengel-From J, Zhang D, Hjelmborg J, Semkovska M. Depressive symptoms, cognitive functions and daily activities: An extended network analysis in monozygotic and dizygotic twins. J Affect Disord. 2025;368:398-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Werneck AO, Araujo RHO, Silva DR, Vancampfort D. Handgrip strength, physical activity and incident mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Maturitas. 2023;176:107789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Stein C, O'Keeffe F, Strahan O, McGuigan C, Bramham J. Systematic review of cognitive reserve in multiple sclerosis: Accounting for physical disability, fatigue, depression, and anxiety. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2023;79:105017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Marx W, Penninx BWJH, Solmi M, Furukawa TA, Firth J, Carvalho AF, Berk M. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023;9:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pérez Bedoya ÉA, Puerta-López LF, López Galvis DA, Rojas Jaimes DA, Moreira OC. Physical exercise and major depressive disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:13223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gravante F, Trotta F, Latina S, Simeone S, Alvaro R, Vellone E, Pucciarelli G. Quality of life in ICU survivors and their relatives with post-intensive care syndrome: A systematic review. Nurs Crit Care. 2024;29:807-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Heissel A, Heinen D, Brokmeier LL, Skarabis N, Kangas M, Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Firth J, Ward PB, Rosenbaum S, Hallgren M, Schuch F. Exercise as medicine for depressive symptoms? A systematic review and meta-analysis with meta-regression. Br J Sports Med. 2023;57:1049-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 76.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zeraatkar D, Ling M, Kirsh S, Jassal T, Shahab M, Movahed H, Talukdar JR, Walch A, Chakraborty S, Turner T, Turkstra L, McIntyre RS, Izcovich A, Mbuagbaw L, Agoritsas T, Flottorp SA, Garner P, Pitre T, Couban RJ, Busse JW. Interventions for the management of long covid (post-covid condition): living systematic review. BMJ. 2024;387:e081318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Baek JE, Hyeon SJ, Kim M, Cho HY, Hahm SC. Effects of dual-task resistance exercise on cognition, mood, depression, functional fitness, and activities of daily living in older adults with cognitive impairment: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2024;24:369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lindvall MA, Holmqvist KL, Svedell LA, Philipson A, Cao Y, Msghina M. START - physical exercise and person-centred cognitive skills training as treatment for adult ADHD: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Andersen BL, Lacchetti C, Ashing K, Berek JS, Berman BS, Bolte S, Dizon DS, Given B, Nekhlyudov L, Pirl W, Stanton AL, Rowland JH. Management of Anxiety and Depression in Adult Survivors of Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3426-3453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Duarte JDS, Alcantara WA, Brito JS, Barbosa LCS, Machado IPR, Furtado VKT, Santos-Lobato BLD, Pinto DS, Krejcová LV, Bahia CP. Physical activity based on dance movements as complementary therapy for Parkinson's disease: Effects on movement, executive functions, depressive symptoms, and quality of life. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0281204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kiah Hui Siew S, Yu J, Teo TL, Chua KC, Mahendran R, Rawtaer I. Technology and physical activity for preventing cognitive and physical decline in older adults: Protocol of a pilot RCT. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0293340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Schneider E, Doll JPK, Schweinfurth N, Kettelhack C, Schaub AC, Yamanbaeva G, Varghese N, Mählmann L, Brand S, Eckert A, Borgwardt S, Lang UE, Schmidt A. Effect of short-term, high-dose probiotic supplementation on cognition, related brain functions and BDNF in patients with depression: a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2023;48:E23-E33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Curran E, Palmer VJ, Ellis KA, Chong TWH, Rego T, Cox KL, Anstey KJ, Westphal A, Moorhead R, Southam J, Lai R, You E, Lautenschlager NT. Physical Activity for Cognitive Health: A Model for Intervention Design for People Experiencing Cognitive Concerns and Symptoms of Depression or Anxiety. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;94:781-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/