Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.112787

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: November 4, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 112 Days and 21.7 Hours

Lumbar interbody fusion (LIF) is the primary treatment for lumbar degenerative diseases. Elderly patients are prone to anxiety and depression after undergoing surgery, which affects their postoperative recovery speed and quality of life. Effective prevention of anxiety and depression in elderly patients has become an urgent problem.

To investigate the trajectory of anxiety and depression levels in elderly patients after LIF, and the influencing factors.

Random sampling was used to select 239 elderly patients who underwent LIF from January 2020 to December 2024 in Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital. General information and surgery-related indices were recorded, and participants completed measures of psychological status, lumbar spine dysfunction, and quality of life. A latent class growth model was used to analyze the post-LIF trajectory of anxiety and depression levels, and unordered multi-categorical lo

Three trajectories of change in anxiety level were identified: Increasing anxiety (n = 26, 10.88%), decreasing anxiety (n = 27, 11.30%), and stable anxiety (n = 186, 77.82%). Likewise, three trajectories of change in depression level were identified: Increasing depression (n = 30, 12.55%), decreasing depression (n = 26, 10.88%), and stable depression (n = 183, 76.57%). Regression analysis showed that having no partner, female sex, elevated Oswestry dysfunction index (ODI) scores, and reduced 36-Item Short Form Health Survey scores all contributed to increased anxiety levels, whereas female sex, postoperative opioid use, and elevated ODI scores all contributed to increased depression levels.

During clinical observation, combining factors to predict anxiety and depression in post-LIF elderly patients enables timely intervention, quickens recovery, and enhances quality of life.

Core Tip: A latent class growth model was constructed to analyze trends in postoperative anxiety and depression levels in elderly patients who had undergone lumbar interbody fusion. Three different trends were found: Increasing, decreasing, and stable levels. Factors influencing increased anxiety included female sex, having no partner, high Oswestry dysfunction index (ODI) scores, and low 36-Item Short Form Health Survey scores, while increased depression contributors comprised female sex, postoperative opioid use, and high ODI scores.

- Citation: Liu XF, Wu YH, Huang GX, Yu B, Xu HJ, Qiu MH, Kang L. Trajectory and influencing factors of changes in anxiety and depression in elderly patients after lumbar interbody fusion. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 112787

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/112787.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.112787

With an aging population, the prevalence of spinal disorders in the elderly is increasing, including conditions such as lumbar disc herniation, lumbar spinal stenosis, and lumbar spondylolisthesis[1]. This has led to an increase in the number of elderly patients undergoing lumbar interbody fusion (LIF)[2]. LIF can enhance the structure of the herniated nucleus pulposus in the lumbar intervertebral disc and lessen its pressure on the surrounding nerve roots or spinal cord canal[3,4]. LIF can also alleviate spinal canal stenosis, thereby improving the mechanical environment of the lumbar spine and providing it with enhanced stability[5,6]. However, the recovery time after LIF is long, and patients need to rest in bed or wear lumbar support for protection[7]. Moreover, the procedure somewhat limits the mobility of the lumbar vertebrae, increases stress on neighboring vertebrae, and causes degenerative changes[8]. These physiological outcomes and the pain during recovery can psychologically burden the patient, leading in severe cases to anxiety and depression[9,10]. These consequences typically reduce the patient’s adherence to treatment, leading to a slower postoperative recovery, which prolongs the negative impact on their physical and mental health[11]. To better understand this phenomenon, this study investigated the trajectory of anxiety and depression levels in elderly patients after LIF and the influencing factors. The findings should provide insights into how to reduce postoperative anxiety and depression in this patient population and enhance their recovery speed and quality of life following LIF.

The literature indicates that roughly 12.3% of post-LIF elderly patients are diagnosed with anxiety and/or depression[12]. Applying a tolerance error of 0.05 and alpha value of 0.05 (two-sided test), power analysis using PASS 25 software generated a required sample size of 185 cases. Considering a 20% loss to follow-up rate, a minimum of 232 cases were required. A total of 276 elderly patients who underwent LIF in Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital between January 2020 and December 2024 were randomly selected. Three inclusion criteria were applied: (1) Age ≥ 60 years; (2) Successful LIF; and (3) Complete clinical and follow-up information. There were four exclusion criteria: (1) Preoperative severe hepatic or renal insufficiency; (2) Preoperative mental disorder or psychiatric disease; (3) Preoperative malignant tumor; and (4) Inability to complete each scale. The final sample comprised 239 patients. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Pingle Orthopedic Hospital (No. PLGSK202400412-3).

General information: Sex, age, body mass index, education level, place of residence, partner status, underlying medical history, smoking history, drinking history, preoperative diagnosis, preoperative course of the disease, and postoperative use of opioids were recorded.

Surgery-related indicators: The fusion level and number of decompression segments were recorded.

Depressive symptoms: Patients completed the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[13], a tool commonly used for screening, diagnosing, and assessing the severity of depression. Each of its nine items is rated on a 4-point scale (0-3), with a maximum total score of 27 points: 0-4, no depression; 5-9, mild depression; 10-14, moderate depression; 15-19, moderately severe depression; And ≥ 20, severe depression. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.860.

Anxiety symptoms: Patients also completed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)[14], a widely recognized scale for screening and assessing the severity of anxiety disorders, especially generalized anxiety disorder. Each of the seven items is rated on a 4-point scale, with a maximum total score of 21 points: 0-4, no anxiety; 5-9, mild anxiety; 10-13, moderate anxiety; 14-18, moderately severe anxiety; And ≥ 19, severe anxiety. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.890.

Lumbar spine dysfunction: Patients’ lumbar spine function was measured six months after LIF using the 10-item Oswestry dysfunction index (ODI)[15]. Internationally, the ODI is the most commonly used scale for assessing the degree of functional impairment in patients with low back pain, specifically measuring the impact of pain on their ability to perform activities of daily living. Each item is rated on a 6-point scale, with a maximum total score of 50 points: 0-4 signifies no loss of function; 5-14 mild loss; 15-24 moderate loss; 25-34 severe loss; And ≥ 35 complete loss. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.87.

Quality of life: The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36)[16] was used to score patients’ quality of life six months after LIF. The items are organized into eight dimensions, and the maximum total score is 100, with a higher score indicating better quality of life. The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.901.

For observation indicators “surgery-related indicators” to “quality of life”, data were collected preoperatively and 1 month, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively.

The Mplus8.3 latent class growth model (LCGM) was used to analyze the trajectories of post-LIF anxiety and depression levels. Smaller statistical values indicate a better fit, and the results of trajectory fitting were not considered when the assigned probability was < 10%. SPSS 27.0 was used to process the data, using “mean ± SD” to express normally distributed continuous variables, and “n (%)” to express count information. Intergroup comparisons were performed using an independent samples t-test, χ2 test, or Fisher’s precision test. Finally, unordered multi-categorical logistic regression analysis was used to identify the influencing factors of anxiety and depression after LIF.

The specific fitting indicators of the anxiety growth model are shown in Table 1. The Akaike information criterion, Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and adjusted BIC all decreased as the number of model classes increased. With five classes, the smallest group size is 5.5%, which is below the 10% threshold; with four classes, the Lo-Mendell-Rubin-adjusted likelihood ratio test (LMR) is not significant. Considering the fitting indicator values, the LCGM with three classes was considered optimal.

| No. | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | LMR | BLRT | Probability |

| 1 | 3823.352 | 3844.211 | 3825.193 | 1.000 | |||

| 2 | 3481.818 | 3513.106 | 3484.579 | 0.984 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.121/0.879 |

| 3 | 3334.745 | 3376.462 | 3338.426 | 0.956 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.115/0.119/0.766 |

| 4 | 3251.977 | 3304.124 | 3256.578 | 0.899 | 0.083 | < 0.001 | 0.114/0.129/0.279/0.477 |

| 5 | 3193.969 | 3256.546 | 3199.491 | 0.924 | 0.003 | < 0.001 | 0.055/0.065/0.134/0.271/0.476 |

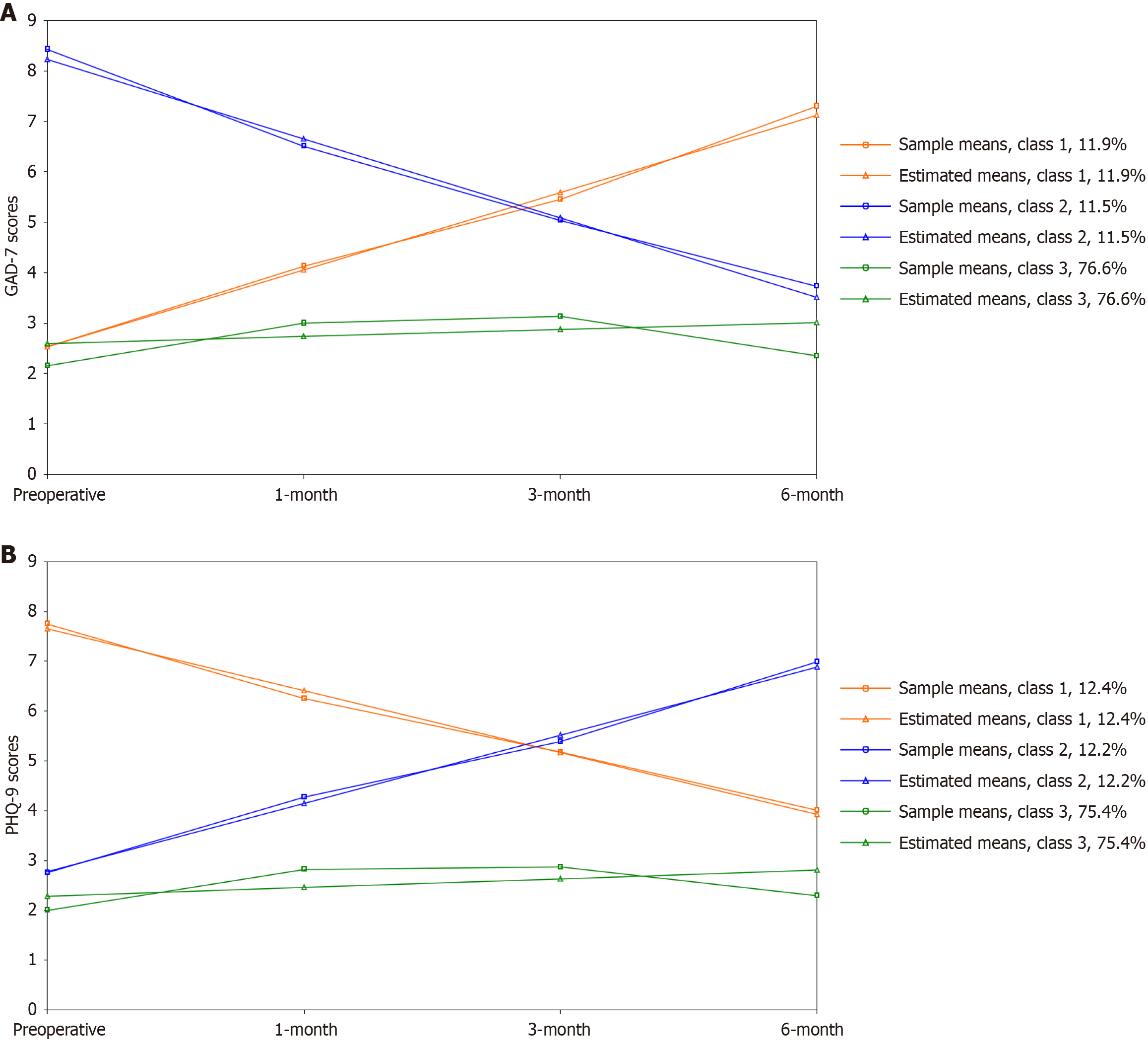

As shown in Figure 1A, the trajectories of the three potential classes were plotted with GAD-7 scores as vertical coordinates and assessment time points as horizontal coordinates. In class A1, the anxiety score was initially low (I = 2.522, P < 0.001) and showed a gradual increasing trend over time (S = 1.532, P < 0.001); therefore, A1 was named the increasing-anxiety group (n = 26, 10.88%). In class A2, patients’ anxiety score was initially high (I = 8.225, P < 0.001) and tended to decrease over time (S = -1.571, P < 0.001); therefore, A2 was named the decreasing-anxiety group (n = 27, 11.30%). In class 3 (A3), the anxiety score was initially moderate (I = 2.594, P < 0.001), slightly increased, and then decreased again over time (S = 0.139, P = 0.100). The overall score was lower than in groups A1 and A2. Therefore, A3 was named the stable-anxiety group (n = 186, 77.82%). The intercepts of the three groups were 2.522 (P < 0.001), 8.225 (P < 0.001), 2.594 (P < 0.001), and slopes were 1.532 (P < 0.001), -1.571 (P < 0.001), and 0.139 (P = 0.100).

Table 2 shows the fitting indicators for the depression growth model. With five classes, the smallest group size is 5.0%, which is below the 10% threshold; with four classes, the LMR is not significant. Taking into account the fitting indicator values, the linear fit LCGM with three classes was considered the optimal choice.

| No. | AIC | BIC | aBIC | Entropy | LMR | BLRT | Probability |

| 1 | 3864.588 | 3885.446 | 3866.428 | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||

| 2 | 3509.856 | 3541.144 | 3512.616 | 0.958 | 0.034 | < 0.001 | 0.163/0.837 |

| 3 | 3354.116 | 3395.833 | 3357.797 | 0.951 | 0.007 | < 0.001 | 0.122/0.124/0.754 |

| 4 | 3316.620 | 3368.767 | 3321.221 | 0.843 | 0.136 | < 0.001 | 0.115/0.120/0.257/0.508 |

| 5 | 3262.497 | 3325.074 | 3268.019 | 0.894 | 0.051 | < 0.001 | 0.050/0.075/0.113/0.234/0.527 |

As shown in Figure 1B, the trajectories of the three potential classes were plotted with PHQ-9 scores as vertical coordinates and assessment time points as horizontal coordinates. In class D1, the depression score was initially high (I = 7.657, P < 0.001) and showed a gradual decreasing trend over time (S = -1.243, P < 0.001); therefore, D1 was named the decreasing-depression group (n = 30, 12.55%). In class D2, patients’ anxiety score was initially moderate (I = 2.783, P < 0.001) and tended to increase over time (S = 1.367, P < 0.001); therefore, D2 was named the increasing-depression group (n = 26, 10.88%). In class D3, the depression score was initially lowest (I = 2.288, P < 0.001), slightly increased, and then decreased again over time (S = 0.174, P = 0.027). As the overall score was lower than in groups D1 and D2, D3 was named the stable-depression group (n = 183, 76.57%). The respective intercepts of the three groups were 7.657 (P < 0.001), 2.783 (P < 0.001), 2.288 (P < 0.001), and respective slopes were -1.243 (P < 0.001), 1.367 (P < 0.001), and 0.174 (P = 0.0.027).

Intergroup comparisons of different anxiety change trajectories (A1, A2, and A3) revealed significant differences among the three groups in terms of sex, partner status, level of fusion, and post- vs pre-surgery change in ODI and SF-36 scores (P < 0.05). The results of intergroup comparisons of different depression change trajectories (D1, D2, and D3) showed significant differences in terms of sex, partner status, postoperative opioid use, and post- vs pre-surgery change in ODI and SF-36 scores (P < 0.05). Table 3 reports the full results of the unifactorial analyses.

| Characteristic | A1 (n = 26) | A2 (n = 27) | A3 (n = 186) | χ2/F value | P value | D1 (n = 30) | D2 (n = 26) | D3 (n = 183) | χ2/F value | P value |

| Sex | 8.320 | 0.016 | 6.101 | 0.047 | ||||||

| Male | 6 (23.08) | 11 (40.74) | 97 (52.15) | 18 (60.00) | 8 (30.77) | 101 (55.19) | ||||

| Female | 20 (76.92) | 16 (59.26) | 89 (47.85) | 12 (40.00) | 18 (69.23) | 82 (44.81) | ||||

| Age (year) | 72.45 ± 5.36 | 71.85 ± 5.50 | 73.37 ± 4.04 | 0.582 | 0.560 | 71.47 ± 4.52 | 72.62 ± 5.78 | 72.49 ± 5.23 | 0.653 | 0.521 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.58 ± 1.17 | 21.59 ± 1.16 | 21.23 ± 0.88 | 1.143 | 0.321 | 21.22 ± 1.20 | 21.75 ± 1.11 | 21.57 ± 1.13 | 1.633 | 0.197 |

| Symptom duration | 5.479 | 0.065 | 4.887 | 0.087 | ||||||

| < 1 year | 9 (34.62) | 18 (66.67) | 92 (49.46) | 18 (60.00) | 17 (65.38) | 84 (45.90) | ||||

| ≥ 1 year | 17 (65.38) | 9 (33.33) | 94 (50.54) | 12 (40.00) | 9 (34.62) | 99 (54.10) | ||||

| Education level | 11.532 | 0.073 | 6.003 | 0.423 | ||||||

| Secondary school | 14 (53.85) | 6 (22.22) | 50 (26.88) | 9 (30.00) | 8 (30.77) | 53 (28.96) | ||||

| Junior high school | 6 (23.08) | 7 (25.93) | 41 (22.04) | 7 (23.33) | 4 (15.38) | 43 (23.50) | ||||

| High school | 3 (11.54) | 10 (37.04) | 53 (28.49) | 10 (33.33) | 11 (42.31) | 45 (24.59) | ||||

| College and above | 3 (11.54) | 4 (14.81) | 42 (22.58) | 4 (13.33) | 3 (11.54) | 42 (22.95) | ||||

| Residence | 2.315 | 0.314 | 2.702 | 0.259 | ||||||

| City | 13 (50.00) | 17 (62.96) | 88 (47.31) | 18 (60.00) | 15 (57.69) | 85 (46.45) | ||||

| Countryside | 13 (50.00) | 10 (37.04) | 98 (52.69) | 12 (40.00) | 11 (42.31) | 98 (53.55) | ||||

| Have a partner | 6.250 | 0.044 | 7.429 | 0.024 | ||||||

| Yes | 9 (34.62) | 18 (66.67) | 107 (57.53) | 19 (63.33) | 8 (30.77) | 105 (57.38) | ||||

| No | 17 (73.08) | 9 (33.33) | 79 (42.47) | 11 (36.67) | 18 (69.23) | 78 (42.62) | ||||

| Smoking | 0.250 | 0.882 | 5.927 | 0.052 | ||||||

| Yes | 13 (50.00) | 15 (55.56) | 94 (50.54) | 11 (36.67) | 18 (69.23) | 93 (50.82) | ||||

| No | 13 (50.00) | 12 (44.44) | 92 (49.46) | 19 (63.33) | 8 (30.77) | 90 (49.18) | ||||

| Alcohol abuse | 0.570 | 0.752 | 3.252 | 0.198 | ||||||

| Yes | 15 (57.69) | 13 (48.15) | 94 (50.54) | 14 (46.67) | 9 (34.62) | 97 (53.01) | ||||

| No | 11 (42.31) | 14 (51.85) | 92 (49.46) | 16 (53.33) | 17 (65.38) | 86 (46.99) | ||||

| History of diabetes | 3.348 | 0.187 | 1.465 | 0.481 | ||||||

| Yes | 17 (65.38) | 17 (62.96) | 93 (50.00) | 19 (63.33) | 13 (50.00) | 95 (51.91) | ||||

| No | 9 (34.62) | 10 (37.04) | 93 (50.00) | 11 (36.67) | 13 (50.00) | 88 (48.09) | ||||

| History of hypertension | 1.301 | 0.522 | 1.704 | 0.427 | ||||||

| Yes | 16 (61.54) | 16 (59.26) | 96 (51.61) | 15 (50.00) | 17 (65.38) | 96 (52.46) | ||||

| No | 10 (38.46) | 11 (40.74) | 90 (48.39) | 15 (50.00) | 9 (34.62) | 87 (47.54) | ||||

| History of coronary heart disease | 0.235 | 0.889 | 5.089 | 0.079 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (53.85) | 15 (55.56) | 95 (51.08) | 21 (70.00) | 11 (42.31) | 92 (50.27) | ||||

| No | 12 (46.15) | 12 (44.44) | 91 (48.92) | 9 (30.00) | 15 (57.69) | 91 (49.73) | ||||

| Preoperative diagnosis | 9.069 | 0.134 | 2.877 | 0.825 | ||||||

| Spondylolisthesis | 17 (65.38) | 10 (37.04) | 121 (65.05) | 16 (53.33) | 15 (57.69) | 117 (63.93) | ||||

| Scoliosis | 4 (15.38) | 7 (25.93) | 24 (12.90) | 6 (20.00) | 4 (15.38) | 25 (13.66) | ||||

| Recurrent disc herniation | 1 (3.85) | 2 (7.41) | 7 (3.76) | 2 (6.67) | 1 (3.85) | 7 (3.83) | ||||

| Stenosis | 4 (15.38) | 8 (29.63) | 34 (18.28) | 6 (20.00) | 6 (23.08) | 34 (18.58) | ||||

| Number of levels decompressed | 8.169 | 0.354 | 10.085 | 0.225 | ||||||

| 1 | 8 (30.77) | 12 (44.44) | 63 (33.87) | 14 (46.67) | 13 (50.00) | 56 (30.60) | ||||

| 2 | 8 (30.77) | 6 (22.22) | 72 (38.71) | 10 (33.33) | 4 (15.38) | 72 (39.34) | ||||

| 3 | 3 (11.54) | 6 (22.22) | 22 (11.83) | 3 (10.00) | 4 (15.38) | 24 (13.11) | ||||

| 4 | 4 (15.38) | 1 (3.71) | 19 (10.22) | 2 (6.67) | 2 (7.69) | 20 (10.93) | ||||

| 5 | 3 (11.54) | 2 (7.41) | 10 (5.39) | 1 (3.33) | 3 (11.54) | 11 (6.01) | ||||

| Number of levels fused | 11.654 | 0.020 | 7.542 | 0.103 | ||||||

| 1 | 8 (30.77) | 12 (44.44) | 87 (46.77) | 10 (33.33) | 10 (38.46) | 87 (47.54) | ||||

| 2 | 8 (30.77) | 8 (29.63) | 74 (39.78) | 14 (46.67) | 7 (26.92) | 69 (37.71) | ||||

| ≥ 3 | 10 (38.46) | 7 (25.93) | 25 (13.44) | 6 (20.00) | 9 (34.62) | 27 (14.75) | ||||

| Chronic opioid use postop | 1.002 | 0.606 | 6.777 | 0.034 | ||||||

| Yes | 14 (53.85) | 17 (62.96) | 98 (52.69) | 11 (36.67) | 18 (69.23) | 82 (44.81) | ||||

| No | 12 (46.15) | 10 (37.04) | 88 (47.31) | 19 (63.33) | 8 (30.77) | 101 (55.19) | ||||

| Post- vs pre-surgery ODI scores | 10.926 | 0.027 | 10.466 | 0.032 | ||||||

| Elevated | 11 (42.31) | 7 (25.93) | 30 (16.13) | 8 (26.67) | 11 (42.31) | 33 (18.03) | ||||

| Reduced | 6 (23.08) | 9 (33.33) | 57 (30.65) | 11 (36.67) | 6 (23.08) | 51 (27.87) | ||||

| No significant change | 9 (34.62) | 11 (40.74) | 99 (53.23) | 11 (36.67) | 9 (34.62) | 99 (54.10) | ||||

| Post- vs pre-surgery SF-36 scores | 10.232 | 0.033 | 10.207 | 0.034 | ||||||

| Elevated | 7 (26.92) | 14 (51.85) | 87 (46.77) | 12 (40.00) | 9 (34.62) | 86 (46.99) | ||||

| Reduced | 9 (34.62) | 6 (22.22) | 24 (12.90) | 6 (20.00) | 11 (42.31) | 27 (14.75) | ||||

| No significant change | 10 (38.46) | 7 (25.93) | 75 (40.32) | 12 (40.00) | 6 (23.08) | 70 (38.25) |

Variables with P < 0.05 in the univariate analyses were included in the unordered multi-categorical logistic regression analyses, which used the latent classes as the dependent variable [with A1 (increased-anxiety) as the reference group]. The regression model likelihood ratio was χ2 = 72.001 (P = 0.001). Results showed that patients who had no partner, were female, had elevated ODI scores, or reduced SF-36 scores were more likely to have increased anxiety levels. Table 4 reports the full results.

| β | SE | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| A1 vs A2 | |||||

| Have a partner | 1.202 | 0.595 | 3.326 | 1.036-10.682 | 0.043 |

| A1 vs A3 | |||||

| Sex | -1.186 | 0.500 | 0.305 | 0.115-0.815 | 0.018 |

| ODI scores | -0.567 | 0.285 | 0.567 | 0.325-0.992 | 0.047 |

| SF-36 scores | 0.596 | 0.295 | 1.815 | 1.012-3.255 | 0.045 |

The same approach was followed for unordered multi-categorical logistic regression analysis of depression level trajectories, with D2 (increased-depression) as the reference group. The regression model’s likelihood ratio was χ2 = 163.655 (P = 0.003). Results showed that patients who were female, postoperative opioid users, or had elevated ODI scores were more likely to have increased depression levels. The full results are reported in Table 5.

| β | SE | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| D1 vs D2 | |||||

| Sex | -1.291 | 0.585 | 0.275 | 0.087-0.866 | 0.027 |

| Chronic opioid use postop | -1.413 | 0.618 | 0.243 | 0.073-0.817 | 0.022 |

| D2 vs D3 | |||||

| Sex | -1.010 | 0.469 | 0.364 | 0.145-0.913 | 0.031 |

| ODI scores | -0.638 | 0.265 | 0.528 | 0.314-0.888 | 0.016 |

This study fitted the LCGM to the respective trajectories of anxiety and depression levels of elderly patients after LIF. For anxiety and depression, three groups were identified in which levels were increasing, decreasing, or stable. As the sample included only patients for whom LIF had been successful, the different trends in anxiety and depression levels could be explained by the different cooperative treatments required during the postoperative recovery period and by individual pain perception. Plausibly, new-onset anxiety or depression explains the increasing trends, while preoperative comorbid anxiety or depression explains the decreasing trends. The results of this study are consistent with those of prior research[17].

Unordered multi-categorical logistic regression analysis showed that patients who were female or had no partner, elevated ODI scores, or reduced SF-36 scores were more likely to have increased anxiety levels. Similarly, patients who were female, postoperative opioid users, or had elevated ODI scores were more likely to have increased depression levels. Female elderly patients are generally more emotionally sensitive than their male counterparts, and thus more susceptible to postoperative anxiety and depression[18].

Partner status had a strong influence on the postoperative trajectory of anxiety, with levels increasing over time in patients without a partner. This could be explained by the lack of companionship, depriving patients of a vital outlet for emotional expression and essential psychological support as they cope with the stress of postoperative recovery[19,20]. In an earlier study of middle-aged and older adults, widowed individuals were found to be at higher risk of depression[21].

Preoperative comorbid anxiety or depressive symptoms have been associated with lower surgical satisfaction and slower recovery after LIF, as well as lower health-related quality of life scores[22]. In another study, the postoperative improvement in ODI scores was lower in patients with (vs without) anxiety and depression[23]. Similarly, the present study found that ODI and SF-36 scores six months after surgery were significantly lower in elderly patients with symptoms of anxiety or depression, compared to those without (P < 0.05). The analysis indicates that when elderly patients experience anxiety or depression, their daily routines, regular eating habits, and activities of daily living can be disrupted[24]. Factors such as irregular meal times and inconsistent sleep schedules may cause a decline in postoperative quality of life, which can harm their prognosis. In the opposite direction, for post-LIF patients with poor quality of life scores on the SF-36[25], psychological stress builds up and has fewer outlets for release, thereby raising anxiety levels.

In an earlier study, patient-reported outcome measurement information system scores were lower for opioid users than for non-users[26], suggesting that chronic opioid use is detrimental to patients’ postoperative recovery. This may be explained by a bidirectional association between opioids and both major depressive disorder and anxiety- and stress-related disorders[27]. This study found that postoperative opioid use significantly influenced the development of depression in post-LIF elderly patients, highlighting the need to monitor these patients with follow-up visits and provide timely intervention if they show signs of depression.

In summary, to protect the mental health of elderly patients after LIF, more attention should be given to patients who are female, have no partner, or who, after surgery, use opioids, score higher on the ODI, or score lower on the SF-36. Clinicians should detect these factors promptly by communicating with elderly patients and their families, and implement early interventions to address psychological problems, promote postoperative recovery, and improve quality of life.

However, this study has limitations. Collecting all data from patients of a single hospital may have introduced bias, and the relatively short follow-up period restricts the findings (if the patient’s anxiety and depression levels remain stable within 3 months, but if the follow-up period is extended to 1-3 years, their anxiety and depression levels may show a downward trend). Future research designs should include multiple patient populations and longer follow-up periods to further validate and refine factors influencing the occurrence of anxiety and depression after LIF surgery.

This study observed three different trajectories of anxiety and depression levels in post-LIF elderly patients, and identified several factors contributing to increased anxiety or depression over time. Female sex, having no partner, elevated ODI scores, and reduced SF-36 scores are important influencing factors of elevated anxiety levels; somewhat similarly, female sex, postoperative use of opioids, and elevated ODI scores are important influencing factors of elevated depression levels. In clinical practice, these factors can be combined to predict the postoperative occurrence of anxiety and depression in elderly patients, enabling prompt intervention to protect their mental health status, thereby ac

| 1. | Zhang Q, Wei Y, Wen L, Tan C, Li X, Li B. An overview of lumbar anatomy with an emphasis on unilateral biportal endoscopic techniques: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jacome FP, Lee JJ, Hiltzik DM, Cho S, Pagadala M, Hsu WK. Single Position Prone Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Review of the Current Literature. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2024;17:386-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Abel F, Tan ET, Chazen JL, Lebl DR, Sneag DB. MRI after Lumbar Spine Decompression and Fusion Surgery: Technical Considerations, Expected Findings, and Complications. Radiology. 2023;308:e222732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hu X, Yan L, Chai J, Zhao X, Liu H, Zhu J, Chai H, Zhao Y, Zhao B. Comparison of the Outcomes of Endoscopic Posterolateral Interbody Fusion and Lateral Interbody Fusion in the Treatment of Lumbar Degenerative Disease: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Orthop Surg. 2025;17:1287-1297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pholprajug P, Kotheeranurak V, Liu Y, Kim JS. The Endoscopic Lumbar Interbody Fusion: A Narrative Review, and Future Perspective. Neurospine. 2023;20:1224-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | An B, Ren B, Han Z, Mao K, Liu J. Comparison between oblique lumbar interbody fusion and posterior lumbar interbody fusion for the treatment of lumbar degenerative diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2023;18:856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Luo J, Tang Y, Cao J, Li W, Zheng L, Lin H. Application of an enhanced recovery after surgery care protocol in patients undergoing lumbar interbody fusion surgery: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res. 2025;20:154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hu X, Yan L, Jin X, Liu H, Chai J, Zhao B. Endoscopic Lumbar Interbody Fusion, Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion, and Open Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion for the Treatment of Lumbar Degenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Global Spine J. 2024;14:295-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mai E, Zhang J, Lu AZ, Bovonratwet P, Kim E, Simon CZ, Kwas C, Allen M, Asada T, Singh N, Tuma O, Araghi K, Korsun M, Kim YE, Heuer A, Vaishnav A, Dowdell J, Wetmore DS, Qureshi SA, Iyer S. Predictors for Failure to Respond to Erector Spinae Plane Block Following Minimally Invasive Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2024;49:1669-1675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Siempis T, Prassas A, Alexiou GA, Voulgaris S, Tsitsopoulos PP. A systematic review on the prevalence of preoperative and postoperative depression in lumbar fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2022;104:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sencaj JF, Siddique MA, Snigur GA, Ward SO, Patel SN, Singh K. Baseline American Society of Anesthesiologists classification predicts worse anxiety and pain interference following Lumbar Interbody Fusion. J Clin Neurosci. 2025;131:110929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bekeris J, Wilson LA, Fiasconaro M, Poeran J, Liu J, Girardi F, Memtsoudis SG. New Onset Depression and Anxiety After Spinal Fusion Surgery: Incidence and Risk Factors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2020;45:1161-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sun XY, Li YX, Yu CQ, Li LM. [Reliability and validity of depression scales of Chinese version: a systematic review]. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2017;38:110-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pheh KS, Tan CS, Lee KW, Tay KW, Ong HT, Yap SF. Factorial structure, reliability, and construct validity of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7): Evidence from Malaysia. PLoS One. 2023;18:e0285435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu H, Tao H, Luo Z. Validation of the simplified Chinese version of the Oswestry Disability Index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1211-6; discussion 1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Joelson A, Sigmundsson FG, Karlsson J. Stability of SF-36 profiles between 2007 and 2016: A study of 27,302 patients surgically treated for lumbar spine diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2022;20:92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merrill RK, Zebala LP, Peters C, Qureshi SA, McAnany SJ. Impact of Depression on Patient-Reported Outcome Measures After Lumbar Spine Decompression. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2018;43:434-439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang X, Rao W, Chen X, Zhang X, Wang Z, Ma X, Zhang Q. The sociodemographic characteristics and clinical features of the late-life depression patients: results from the Beijing Anding Hospital mental health big data platform. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang Z, Zeng Z. Association between personality characteristics and sleep quality among Chinese middle-aged and older adults: evidence from China family panel studies. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:2427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Alzahrani N. The effect of hospitalization on patients' emotional and psychological well-being among adult patients: An integrative review. Appl Nurs Res. 2021;61:151488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wanjau MN, Möller H, Haigh F, Milat A, Hayek R, Lucas P, Veerman JL. Physical Activity and Depression and Anxiety Disorders: A Systematic Review of Reviews and Assessment of Causality. AJPM Focus. 2023;2:100074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Inose H, Kato T, Matsukura Y, Hirai T, Yoshii T, Kawabata S, Takahashi K, Okawa A. Factors influencing the long-term outcomes of instrumentation surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: a post-hoc analysis of a prospective randomized study. Spine J. 2023;23:799-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Goyal DKC, Stull JD, Divi SN, Galetta MS, Bowles DR, Nicholson KJ, Kaye ID, Woods BI, Kurd MF, Radcliff KE, Rihn JA, Anderson DG, Hilibrand AS, Kepler CK, Vaccaro AR, Schroeder GD. Combined Depression and Anxiety Influence Patient-Reported Outcomes after Lumbar Fusion. Int J Spine Surg. 2021;15:234-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu NW, Yang F, Xia J, Ma TP, Yu C, Li NX. [Analysis of the Status of Depression and the Influencing Factors in Middle-Aged and Older Adults in China]. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2021;52:767-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen M, Peng DY, Hou WX, Li Y, Li JK, Zhang HX. Study of quality of life and its correlated factors in patients after lumbar fusion for lumbar degenerative disc disease. Front Surg. 2022;9:939591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wague A, O'Donnell JM, Stroud S, Filley A, Rangwalla K, Baldwin A, El Naga AN, Gendelberg D, Berven S. Association between opioid utilization and patient-reported outcome measures following lumbar spine surgery. Spine J. 2024;24:1183-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Rosoff DB, Smith GD, Lohoff FW. Prescription Opioid Use and Risk for Major Depressive Disorder and Anxiety and Stress-Related Disorders: A Multivariable Mendelian Randomization Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:151-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 28.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/