Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111972

Revised: August 11, 2025

Accepted: September 10, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 136 Days and 0.4 Hours

Patients with major depression (MD) exhibit conditional reasoning dysfunction; however, no studies on the event-related potential (ERP) characteristics of con

To investigate the ERP characteristics of conditional reasoning in MD patients and explore the neural mechanism of cognitive processing.

Thirty-four patients with MD and 34 healthy controls (HCs) completed ERP measurements while performing the Wason selection task (WST). The cluster-based permutation test in FieldTrip was used to compare the differences in the mean amplitudes between the patients with MD and HCs on the ERP components under different experimental conditions. Behavioral data [accuracy (ACC) and reaction times (RTs)], the ERP P100 and late positive potentials (LPPs) were analyzed.

Although the mean ACC was greater and the mean of RTs was shorter in HCs than in MD patients, the differences were not statistically significant. However, across both groups, the ACC in the precautionary WST was greater than that in the other tasks, and the RTs in the abstract task were greater than those in the other tasks. Importantly, compared with that of HCs, the P100 of the left centroparietal sites was significantly increased, and the early LPP was attenuated at parietal sites and increased at left frontocentral sites; the medium LPP and late LPP were in

Patients with MD have conditional reasoning dysfunction and exhibit abnormal ERP characteristics evoked by the WST, which suggests neural correlates of abnormalities in conditional reasoning function in MD patients.

Core Tip: To our knowledge, this investigation represents the initial application of the Wason selection task to assess the neurocognitive mechanisms associated with conditional reasoning in patients with major depression (MD). The observed event-related potential differences between healthy controls and MD patients provide critical neurophysiological evidence for understanding the neural substrates of conditional reasoning and may guide targeted interventions for MD.

- Citation: Li JX, Lu MC, Wu LA, Li W, Li Y, Li XP, Liu XH, Gao XZ, Zhou ZH, Zhou HL. Neural correlates of conditional reasoning dysfunction in major depression: An event-related potential study with the Wason selection task. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 111972

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/111972.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.111972

Major depression (MD) is a prevalent psychiatric condition characterized by persistent and pervasive low mood, loss of interest or pleasure in previously enjoyable activities, and an assortment of cognitive, emotional, and somatic symptoms[1,2]. Despite significant advances in the understanding and treatment of MD, challenges remain in achieving sustained remission for all patients, highlighting the need for continued research into the biological underpinnings and preventive strategies for this complex and burdensome disorder[3].

MD is increasingly recognized as a condition marked by significant cognitive dysfunction[3,4]. Cognitive deficits in individuals with MD encompass a broad range of domains[5]. Clinically, cognitive dysfunction in MD has significant implications for functional outcomes, which has led to growing interest in cognitive remediation strategies[6]. Research has reported that MD is associated with significant cognitive alterations that extend into higher-order reasoning processes, including conditional reasoning[7]. Conditional reasoning refers to the cognitive ability to process and evaluate “if–then” statements, enabling individuals to draw inferences, solve problems, and engage in complex decision-making[8]. It encompasses both logical reasoning under abstract conditions and reasoning about real-life contingencies, playing a critical role in daily functioning and adaptive behavior[9]. One of the most influential paradigms used to investigate conditional reasoning is the Wason selection task (WST), which provides a rigorous experimental framework for exa

Several studies have explored reasoning performance in MD patients. For example, a study examining logical reasoning revealed that depressed individuals experienced greater difficulty rejecting invalid inferences, especially when these inferences were aligned with negative emotional content. These findings resonate with those of cognitive models of depression, which suggest that depressive schemas bias cognitive processes, including reasoning, toward negative and maladaptive interpretations[7]. Specifically, research using the WST has provided insights into reasoning biases in MD patients. Studies have shown that depressed patients display decreased performance on the WST, possibly due to reduced cognitive flexibility and working memory constraints. Moreover, a study revealed that when emotional content embedded in reasoning tasks further modulates performance, depressed individuals demonstrate reasoning biases when conditional rules are emotionally laden, tending toward interpretations consistent with negative affect[13].

Neuroimaging evidence complements behavioral findings, indicating altered activation in regions implicated in logical reasoning, such as the prefrontal cortex (PFC) and anterior cingulate cortex, during conditional reasoning in MD patients. For example, a previous study highlighted the role of emotional salience in modulating prefrontal engagement during reasoning, suggesting potential mechanisms through which affective disturbances in MD interfere with logical thought processes[14].

Despite these advances, the precise nature and neural mechanisms of conditional reasoning deficits in MD patients remain areas for further investigation. To date, few studies have directly targeted conditional reasoning as a primary cognitive domain in MD. Furthermore, there are no reports on applying the WST to investigate the neural mechanism of abnormal conditional reasoning function in MD patients.

Previous research has revealed that the accuracy (ACC) of individuals in conditional reasoning tasks is not particularly high. Researchers suggest that this is due to the excessive abstraction of the WST[15]. A study indicated that the app

Event-related potentials (ERPs) are time-locked electrophysiological responses that appear on an ongoing electroencephalogram (EEG) and are triggered by specific sensory, cognitive, or motor events. Owing to the high temporal re

To date, no studies on the ERP characteristics of conditional reasoning in patients with MD have been reported. Further investigations of the ERP characteristics of conditional reasoning in the context of MD would be helpful in understanding the neural process of conditional reasoning. Understanding the nuances of conditional reasoning deficits in MD patients could inform cognitive remediation strategies. Moreover, insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these deficits could provide novel targets for pharmacological and neuromodulatory treatments.

In this study, social contract, precautionary, descriptive, and abstract WSTs were employed to investigate the neural process of conditional reasoning. The aim of this study was to explore the ERP characteristics of conditional reasoning and further investigate the neural mechanisms of cognitive processing with abnormal conditional reasoning in patients with MD under different types of rules.

This study was conducted from January 1 to June 30, 2025, at the Department of Psychology, Affiliated Mental Health Center of Jiangnan University. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Mental Health Center of Jiangnan University (Reference No. WXMHCIRB2025 LLky013) and adhered to the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki. Before participating, all individuals were thoroughly informed about the experimental procedures and equipment and provided written informed consent.

The participants in this study included patients with MD and healthy controls (HCs). The diagnosis of MD was established according to the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V). The inclusion criteria for the MD group were as follows: (1) Aged between 18 and 65 years; (2) Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, 17-item edition (HAMD-17) score ≥ 17[19]; (3) No physical/neurological illnesses, traumatic brain injury, or substance abuse history; and (4) intact auditory/visual, verbal, and writing abilities. The exclusion criteria for MD patients were as follows: (1) The presence of any physical illness as determined by clinical evaluations and medical records; (2) A history of substance misuse or dependence; and (3) A history of modified electroconvulsive therapy within the past 12 months.

For HCs, the inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) No diagnosis of any psychiatric disorder according to the DSM-V criteria; (2) No current use of medications affecting cognitive function; and (3) Aged between 18 and 65 years.

The sample size was estimated using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich Heine University, Germany), with parameter settings reaching a statistical power of 0.95 (1 - β = 0.95), and the α level of the F test was 0.05. This calculation indicated that each group required at least 25 participants. MD patients were recruited from the Affiliated Mental Health Center of Jiangnan University, China. HCs were recruited through community advertisements among residents living in Wuxi city, Jiangsu Province, China. A total of 40 MD patients and 35 HCs participated in the study. Additionally, six patients with MD were excluded from further analyses because of poor electrode contact, and one HC was excluded because of frequent blinks or muscle artifacts in their recordings. Both MD patients and HCs were compensated with 300.00 Chinese yuan.

A semi-structured interview based on the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-V was employed to gather so

Stimuli: In accordance with the methodology of previous research[17,21], eight social contract WSTs, eight precautionary WSTs, and eight descriptive WSTs were employed in the present study. All the conditional rules were translated into Chinese by experienced English-Chinese bilingual individuals, with certain terms localized (e.g., replacing “Philadelphia” with “Wuxi”). The number of Chinese characters in each problem closely matched across categories (social contract: Mean = 18.33, SD = 1.99, range = 15-21; precautionary: Mean = 18.53, SD = 2.56, range = 15-22; descriptive: Mean = 21.07, SD = 1.75, range = 19-25). Additionally, eight abstract WSTs were selected from the materials used in a previous report[22].

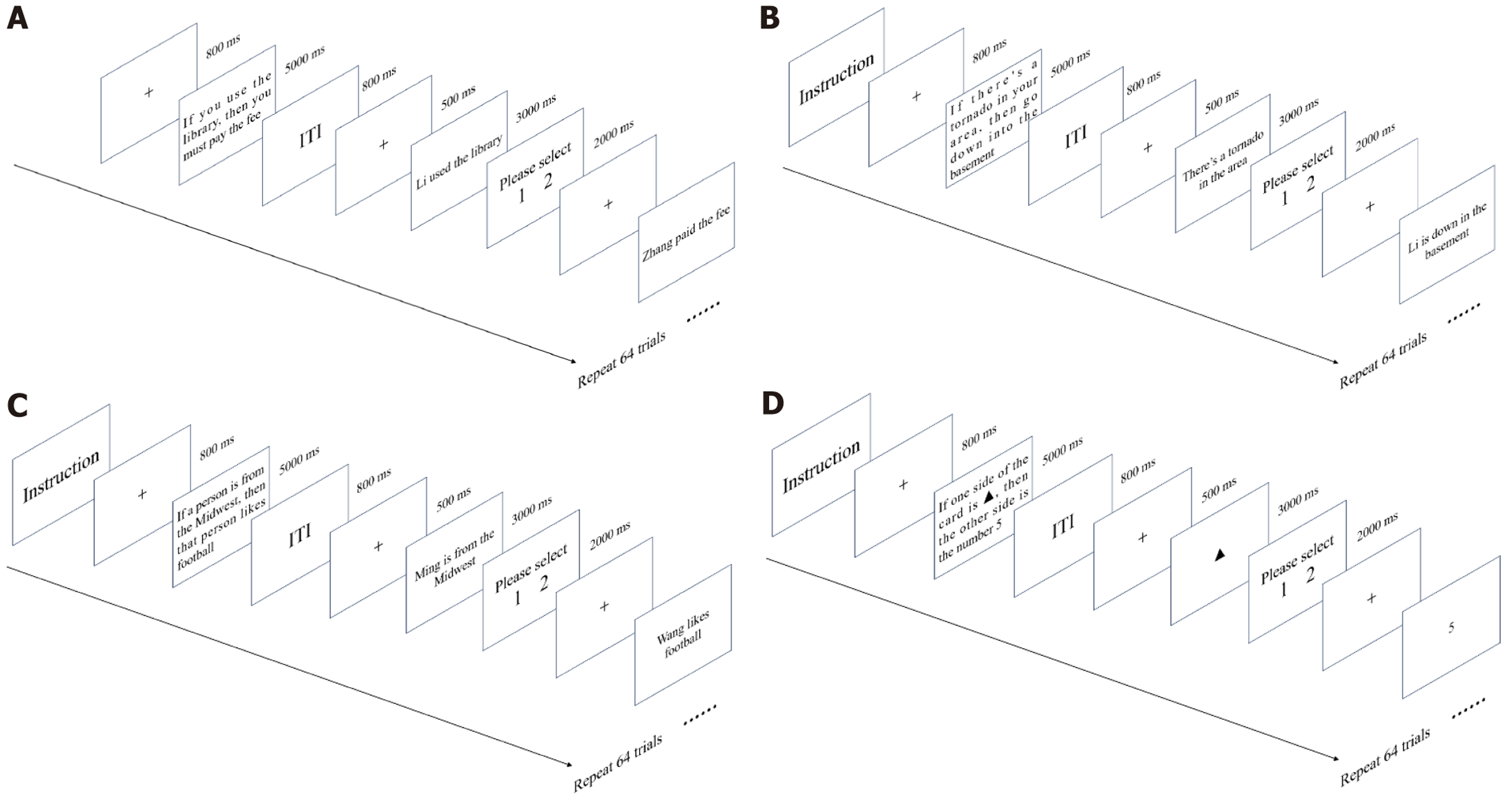

WSTs: The experimental procedure followed the methodology reported in previous studies[10,21]. As illustrated in Figure 1, each trial began with a centrally presented fixation cross lasting randomly between 800 and 1000 ms. Following the fixation, a rule was displayed at the center of the screen for 5000 ms (e.g., “If you use the library, then you must pay the fee”). A card (e.g., “Ming used the library”) subsequently appeared on the screen for 3000 ms. When the card was displayed, the participants were instructed to reason logically and determine whether the card represented a potential violation of the rule in preparation for the subsequent selection. The participants were required to decide whether to turn over the card by pressing the “1” key or, if they decided not to turn over the card, pressing the “2” key. To counterbalance responses, half of the participants had the opposite key assignments. The responses were to be made without delay when the response cue appeared, which remained on the screen for 2000 ms. After an intertrial fixation period of 800 ms, the next card was presented. Breaks were provided every 64 trials, with the duration determined by each participant’s pre

The WST consisted of one rule paired with four cards. For example, if the rule was “If P, then Q”, the corresponding cards were P, Q, not-P, and not-Q.

After fitting the EEG cap and reducing electrode impedance, the participants received written instructions for the task. Following the reading of instructions, the experimenter provided additional explanations and guided participants through practice exercises. The experimenter’s explanations were standardized to avoid influencing the participants’ reasoning processes. The participants then completed 16 practice trials of a computerized exercise, which was repeated if necessary. Upon completion of the practice, the formal experiment commenced.

The four content types—social contract, precautionary, descriptive, and abstract—correspond to experiments 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. Each experiment involved eight rules (four trials per rule), and the corresponding cards were pre

The participants were instructed to remain as still as possible and to avoid head movements throughout the task. Breaks were provided between experiments, with the duration adjusted on the basis of individual preference.

Reaction times (RTs) and ACC were recorded for each trial across the four experiments. RT was defined as the interval between the onset of the card and the participant’s keypress response. The rules were scored as follows: A perfect answer (selecting P and non-Q cards, not selecting Q and non-P cards) was awarded 1 point, whereas all other answers were awarded 0 points. The maximum score for each rule under each condition was 8 points, and ACC was calculated as the ratio of correct scores to the total scores.

EEGs were continuously recorded with a 64-channel Ag-AgCl elastic cap arranged according to the International 10-20 System using the BioSemi ActiveTwo system. The signals were bandpass-filtered between 0.05 Hz and 100 Hz and digitized at a sampling rate of 500 Hz. A vertical electrooculogram was recorded using electrodes placed above and below the left eye, and a horizontal electrooculogram was recorded via electrodes positioned at the outer canthi of both eyes. The left and right mastoids served as reference electrodes, and the ground electrodes were positioned below the left clavicle. All interelectrode impedances were kept below 5 kΩ throughout the data acquisition.

In this study, ERP waveforms were time-locked to the onset of each card stimulus. The EEG epochs comprised a total duration of 1000 ms, including a 200 ms prestimulus baseline. Following data acquisition, offline processing was per

To explore the ability of the brain to stabilize neural responses, a spatiotemporal EEG/ERP data clustering method has been used as an innovative research strategy to identify the time windows of key ERP components effectively[25-27]. The Microstate EEGlab toolbox incorporates standard k-means clustering for ERP analysis alongside conventional microstate analytic approaches[28,29]. FieldTrip is a MATLAB toolbox that provides comprehensive EEG analysis functions, inc

Data analysis was performed using the Statistical Program for the Social Sciences software 21.0 (SPSS, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). First, independent samples t-tests were used to examine between-group differences in age and education between MD patients and HCs. The Pearson χ2 test was used for the comparison of sex distributions. For the behavioral data, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the ACC and RTs. Effect sizes were estimated using η2. The degrees of freedom of the F ratio were corrected using the Greenhouse-Geisser method.

The cluster-based permutation test in FieldTrip was used to compare the differences in the mean amplitudes between the two groups on the ERP components under different experimental conditions. We used the clustering parameter maxsum, the number of iterations was 3000, and the statistical significance threshold was set at P < 0.05.

Pearson correlation analysis was used to investigate potential correlations between P100, LPP, and behavioral data and the HAMD-17 scores.

As shown in Table 1, there were no differences in age, sex, education level or handedness between the MD group and the HC group. All MD patients were receiving antidepressant treatment; i.e., nine were taking sertraline (mean dose: 195.0 ± 22.1 mg/day), seven were taking escitalopram oxalate (mean dose: 16.1 ± 3.1 mg/day), eight were taking duloxetine (mean dose: 60.5 ± 18.2 mg/day), five were taking vortioxetine (mean dose: 10.0 ± 0.2 mg/day), and eight were taking venlafaxine (mean dose: 235.1 ± 22.3 mg/day). The mean fluoxetine-equivalent dose across patients was 33.9 ± 12.6 mg/day, which was calculated according to a previously established conversion method[30].

| Variables | MD (n = 34) | HC (n = 34) | Statistical analysis |

| Age (years) | 29.00 ± 9.28 | 31.94 ± 7.16 | t = 1.462, P = 0.148 |

| Sex (M/F) | 20/14 | 18/16 | χ2 = 0.239, P = 0.625 |

| Education (years) | 13.29 ± 2.62 | 14.44 ± 2.09 | t = 1.994, P = 0.051 |

| Age at onset (years) | 26.10 (6.57) | - | - |

| Handedness (R/M/L) | 13/12/12 | 12/10/12 | χ2 = 0.601, P = 0.253 |

| HAMD-17 | 22.88 ± 3.81 | - | - |

| Anxiety/somatization | 7.82 ± 2.44 | - | - |

| Weight loss | 0.82 ± 0.90 | - | - |

| Cognitive impairment | 4.76 ± 1.84 | - | - |

| Retardation | 6.15 ± 1.54 | - | - |

| Sleep disturbance | 3.32 ± 1.77 | - | - |

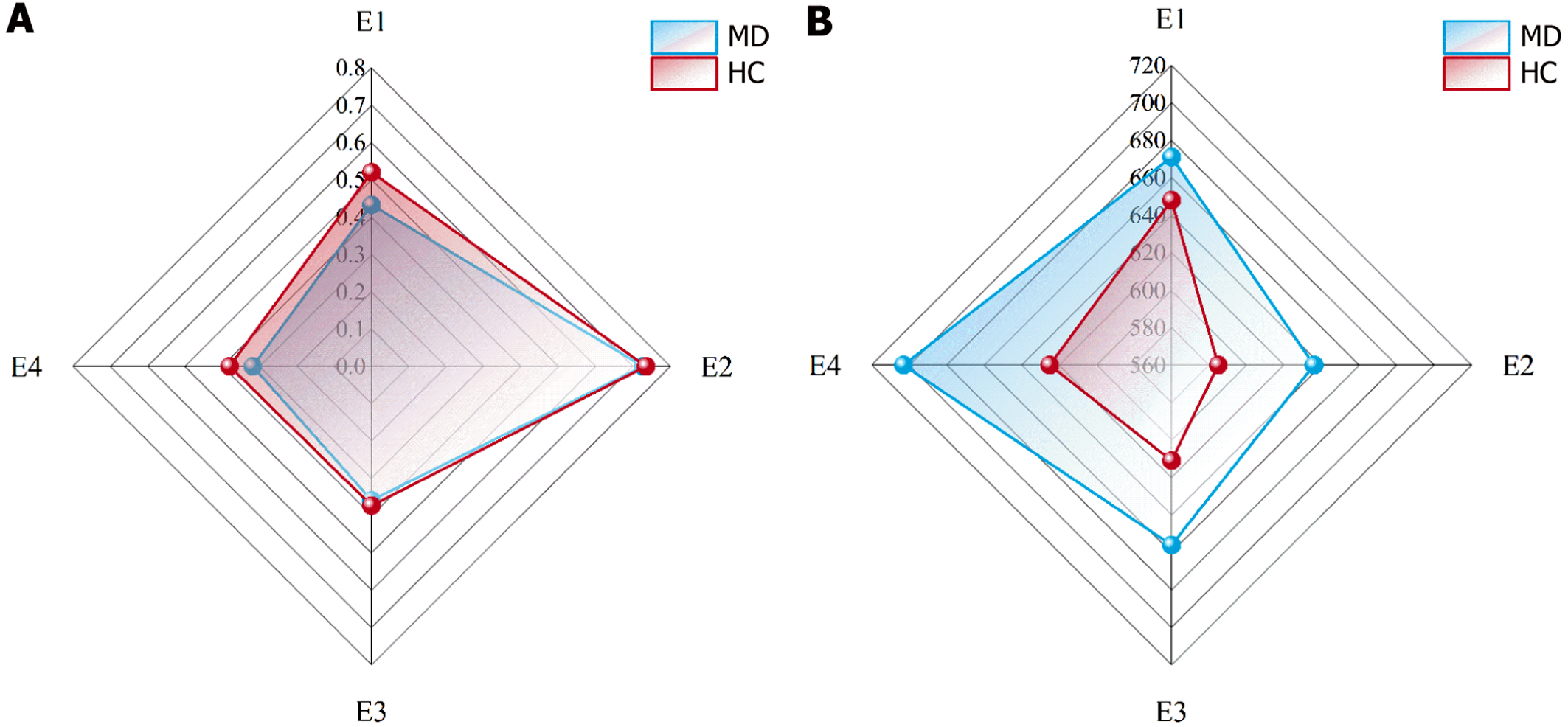

As shown in Figure 2, when group (MD vs HC) was used as the between-subjects factor and experiment (experiment 1 vs experiment 2 vs experiment 3 vs experiment 4) was used as the within-subjects factor, the ACC and RTs were compared with 2 (group) × 4 (experiment) repeated-measures ANOVA. For the ACC, Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated a violation of the sphericity assumption (W = 0.55, P = 0.00); therefore, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied (ε = 0.71). The results revealed a significant main effect of experiment, F (2.12, 139.73) = 46.71, P = 0.000, η² = 0.410. The ACC in experiment 2 was significantly greater than that in experiments 1, 3, and 4. The between-group main effect was not significant (P = 0.481).

For RTs, Mauchly’s test of sphericity indicated a violation of the sphericity assumption (W = 0.68, P = 0.00), nec

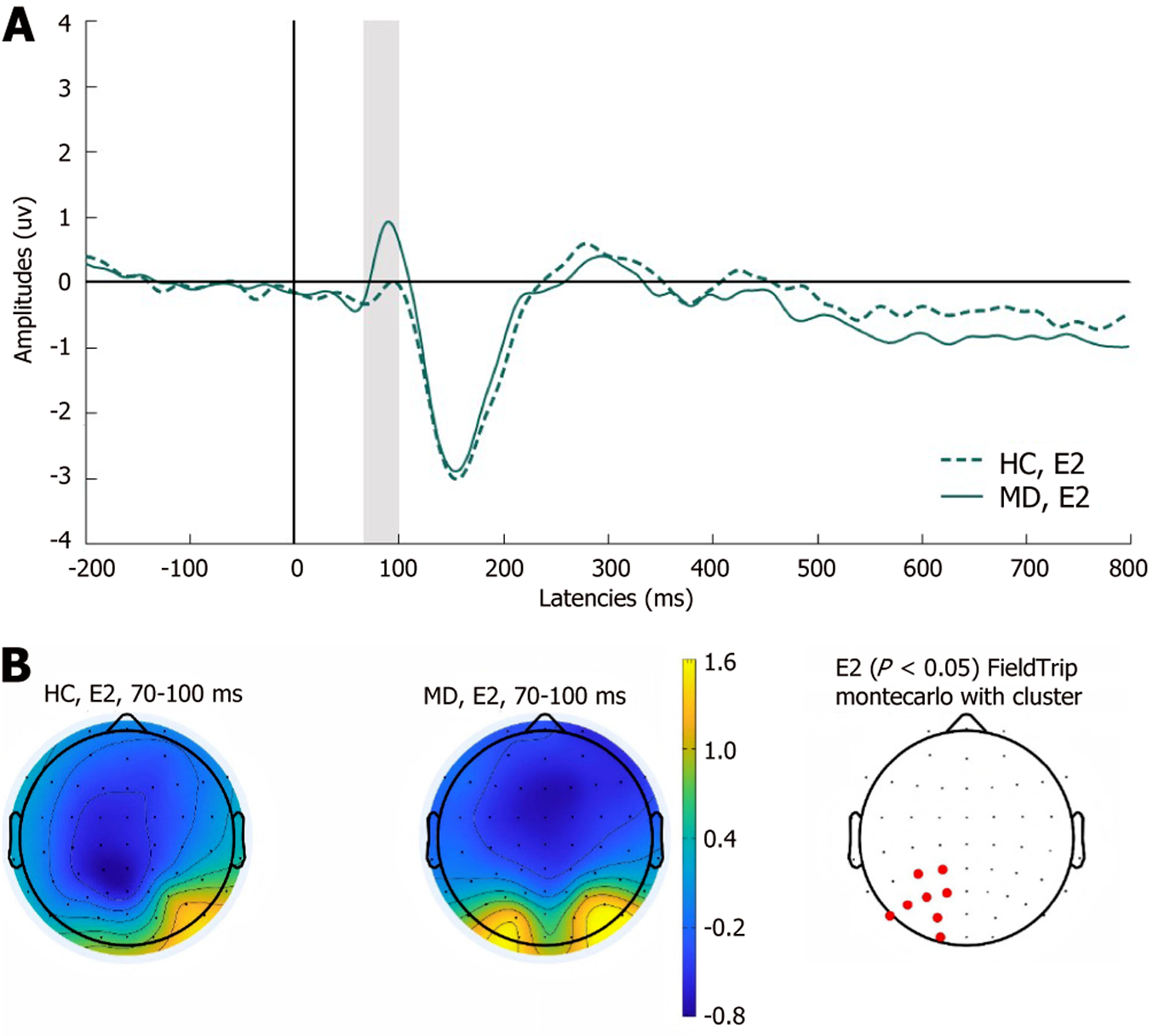

P100: As shown in Figure 3, the P100 of the left centroparietal sites was significantly increased in the MD group in experiment 2 (P < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between the two groups in the remaining experiments.

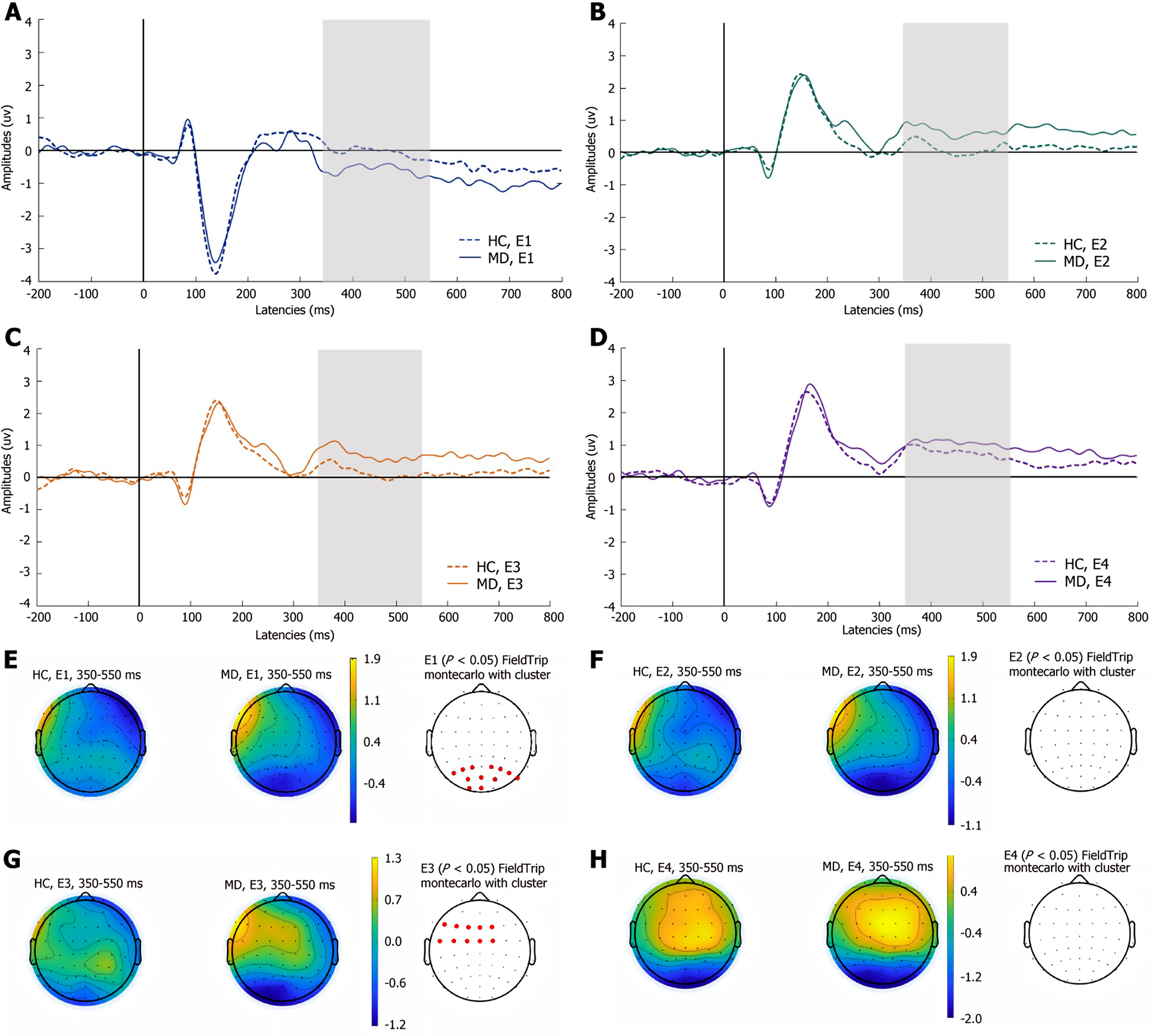

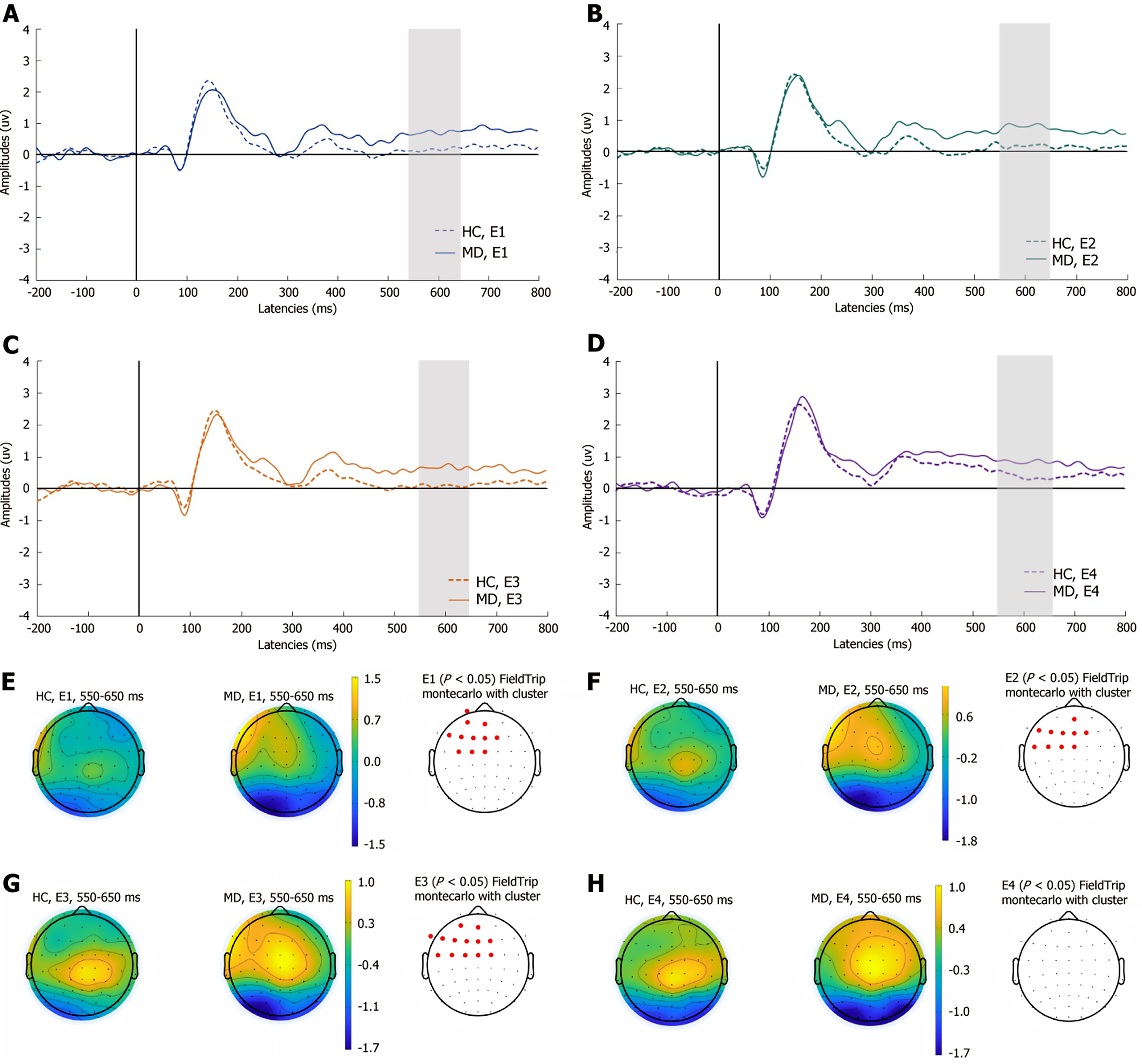

LPP: As shown in Figure 4, compared with HCs, the early LPP was significantly attenuated at parietal sites (P1-P8, PO3, POz, PO4, O1, Oz) in experiment 1, whereas in experiment 3, the early LPP was significantly increased at left frontocentral sites (F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCz, FC2) in the MD group (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the two groups in experiments 2 and 4.

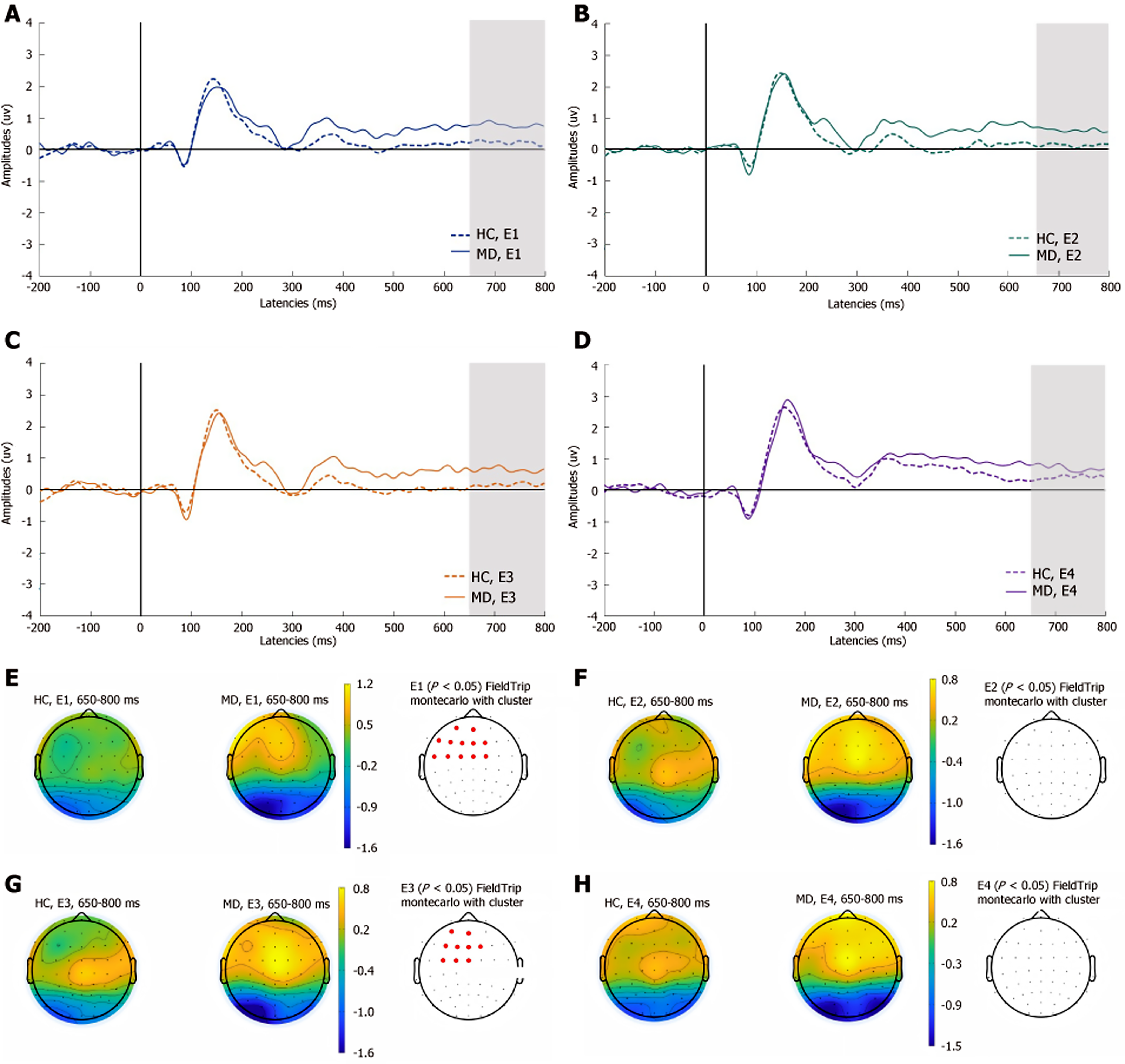

As shown in Figure 5, in the MD group, compared with that of HCs, the medium LPP was significantly greater at the left frontocentral sites (Fp1, AF3, AFz, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC3, FC1, and FCz) in experiment 1; in experiment 2, the medium LPP was significantly greater at the left frontocentral sites (AFz, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC5, FC3, FC1, and FCz); and in experiment 3, there was a significant increase in the medium LPP at the left frontocentral sites (AF3, AFz, F7, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCz, and FC2; P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the two groups in experiment 4.

As shown in Figure 6, compared with that in HCs, the late LPP was significantly greater at the left frontocentral sites (AF3, AFz, F5, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC5, FC3, FC1, FCz, and FC2) in experiment 1, and in experiment 3, the late LPP at the left frontocentral sites (AF3, AFz, F3, F1, Fz, F2, FC3, FC1, and FCz) was significantly greater in the MD group (P < 0.05). The remaining two experiments did not show significant differences in the late components of LPPs between the two groups.

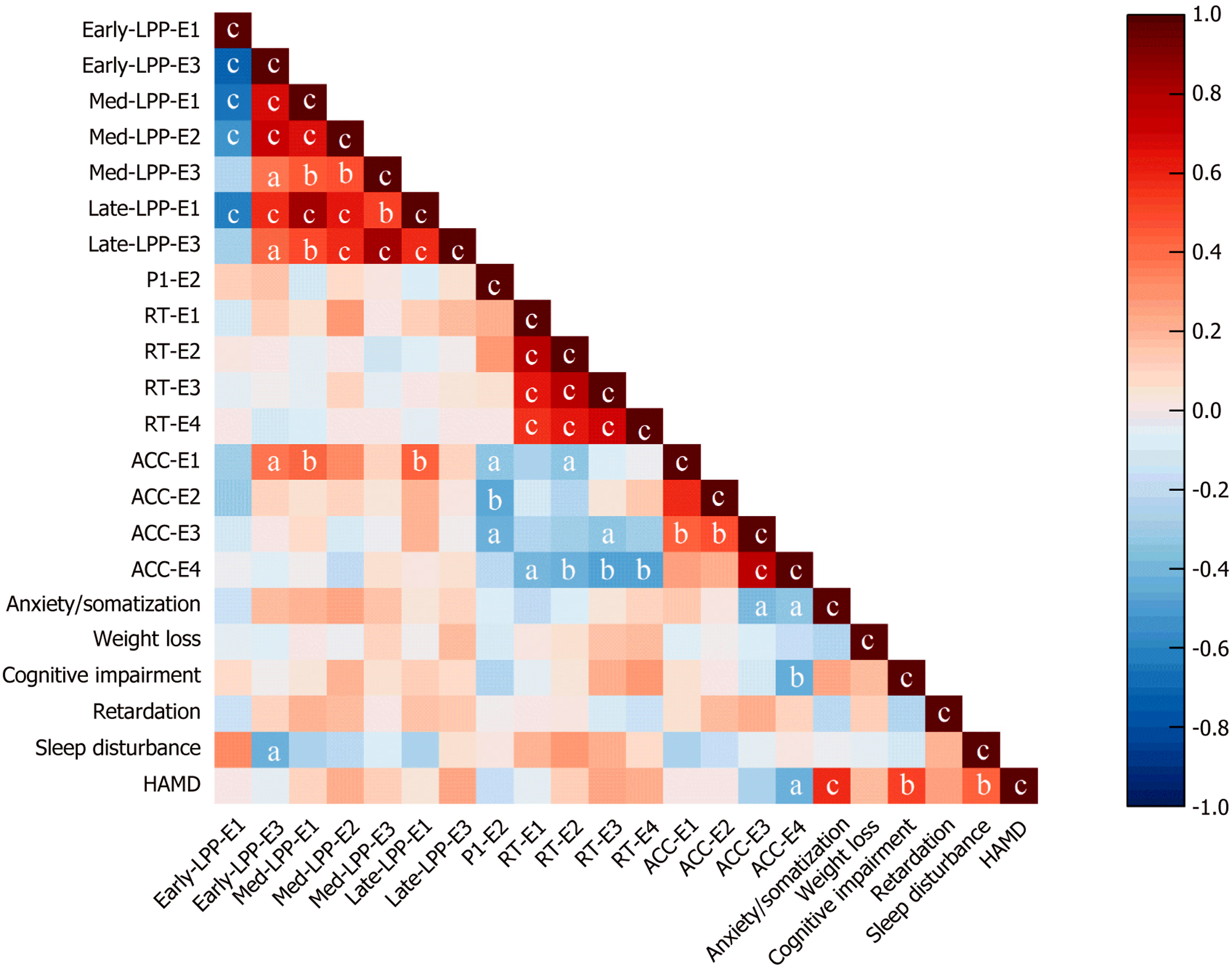

As shown in Figure 7, moderate correlations were observed for three variables: HAMD-17 scores, behavioral data, and ERP amplitudes (P100, LPPs).

The ACC for experiment 1 was positively correlated with the medium LPP (r = 0.40, P < 0.01) and the late LPP (r = 0.44, P < 0.01), whereas the ACC for experiment 2 was negatively correlated with the P100 (r = -0.46, P < 0.01). The ACC for experiment 3 was significantly negatively correlated with the RT (r = -0.34, P < 0.05). The ACC for experiment 4 was significantly correlated with the RT for each trial. The sleep disturbance factor score of the HAMD-17 was negatively correlated with the early LPP in experiment 3 (r = -0.43, P < 0.05), and the total HAMD-17 score was negatively correlated with the ACC in experiment 4 (r = -0.43, P < 0.05).

This study is the first in which the ERP characteristics of conditional reasoning with measurements of ERPs during the WST was investigated and in which the neuroelectrophysiological mechanism of the cognitive processing of conditional reasoning dysfunction in MD patients was explored. Specifically, we used the cluster-based permutation test in FieldTrip to compare the differences in the mean amplitudes of the ERP components between patients with MD and HCs under different experimental conditions.

Conditional reasoning constitutes a fundamental aspect of human cognition, referring to the mental processes by which individuals evaluate, infer, and draw conclusions on the basis of conditional statements[31,32]. This reasoning process underpins numerous cognitive functions, including problem-solving, decision-making, and scientific hypothesis testing[33-35]. Research employing the WST has revealed that human reasoning often deviates from strict logical norms, with many individuals selecting cards consistent with the affirmation of the rule (confirmation bias) rather than against the rule[36-38]. Variations of the task have demonstrated that performance improves substantially when the conditional rules are embedded in familiar, concrete, or social contexts—an observation that has fueled debates between theories emphasizing abstract logical competence and those highlighting pragmatic, content-sensitive reasoning processes[10,39,40].

In this study, the behavioral data revealed that although the mean ACC was lower and the mean RTs were longer in MD patients than in HCs, the differences were not statistically significant. This outcome might not indicate that the ACC and RT of depressed patients are similar to those of HCs when they perform the WST. This might be due to the relatively small sample size. Future large-sample studies are needed to further confirm these findings. However, in both MD patients and HCs, the ACC in the precautionary WST was greater than that in the other tasks, and the RT in the abstract WST was greater than those in the other tasks. This finding aligns with prior research demonstrating markedly different performance rates depending on task framing: Whereas only a minimal proportion (approximately 4%) of participants provided correct responses in the standard WST (abstract), the ACC rate increased substantially to 62% when the task incorporated familiar, contextually meaningful rules such as social contracts[15,16].

Additionally, in the precautionary WST, the MD group presented greater amplitudes for the P100 component at the left centroparietal sites than did the HC group, which suggests that initial processing and attentional engagement might differ between the two groups during precautionary reasoning. MD patients exhibit heightened emotional reactivity to self-referential safety-related lexical stimuli, as evidenced by increased attentional bias. The early LPP amplitudes in MD patients was attenuated at parietal sites in the social contract WST and increased at left frontocentral sites in the descriptive WST. Empirical studies indicate that the early LPP component is highly sensitive to internally generated emotional processing[41]. Compared with HCs, MD patients demonstrate reduced interpersonal communication motivation[3], which manifests neurocognitively as diminished cortical activation during social contract processing—a paradigm requiring reciprocal social exchange evaluation. Notably, this attenuation is absent during the comprehension of nonaffective descriptive sentences, suggesting modality-specific deficits in socio-emotional integration. Moreover, the medium LPP is modulated by attentional resource allocation. Previous studies have shown that MD patients exhibit significant executive dysfunction, which is primarily mediated by the frontal lobe, particularly the PFC[42,43]. Our findings extend this evidence by demonstrating enhanced medium LPP amplitude over the left frontal region in depressed patients. This electrophysiological pattern indicates that these individuals require greater cognitive effort mobilization when performing tasks that involve detection of active rule violation. The late LPP amplitudes increased at the left frontocentral sites, suggesting that the cognitive resources input by MD patients are significantly greater than HCs. This result may reflect deeper processing related to ongoing evaluations of stimulus meaning. MD patients typically display maladaptive rumination, a cognitive pattern distinct from the transient task engagement observed in HCs. This persistent overprocessing is neurophysiologically reflected in sustained amplitude enhancement of the late LPP in the WST, indicating abnormally prolonged allocation of cognitive resources to decision-making processes. The above results are consistent with the findings that MD patients have abnormal conditional reasoning dysfunction.

The ACC for experiment 1 was positively correlated with the medium LPP and the late LPP. These findings suggest that during the social contract WST, MD patients may require greater cognitive resource allocation than HCs do to maintain equivalent task ACC, even when performing ostensibly simple discriminations. This compensatory cognitive effort manifests neurophysiologically through enhanced LPP amplitudes. However, for precautionary tasks, MD patients who exhibit lower ACC demonstrate stronger P100 amplitudes activation instead. When individuals face potential threats, they adopt preventive measures to minimize risk. Previous studies have shown that for tasks related to threat assessment, HCs can arrive at the correct answer through straightforward reasoning[44]. However, our findings indicate that in such tasks, the overthinking characteristic of depression may instead lead to poorer performance in these patients. The sleep disturbance factor score of the HAMD-17 was negatively correlated with the early LPP in experiment 3, which may reflect abnormal emotional processing in MD patients. MD patients who obtained higher scores on the HAMD, reflecting more severe depressive symptoms, had significantly lower ACC in abstract reasoning tasks. No similar correlation was found for the other tasks. This pattern may be attributed to the inherently complex nature of abstract reasoning tasks. Previous studies have indicated that even HCs frequently perform poorly on such tasks because of inherent challenges in rule abstraction[15]. Therefore, among MD patients, increasing depressive symptom severity is associated with progressively greater cognitive dysfunction, which directly contributes to their impaired performance on these demanding tasks.

There are two limitations of this study. First, owing to the relatively small sample size of the study, our results are preliminary. In the future, a large sample with the same parameters will be needed to repeat this outcome. Second, owing to the low spatial resolution of ERP devices, future research will need to combine high spatial resolution fMRI or mag

Patients with MD have conditional reasoning dysfunction and exhibit abnormal ERP characteristics evoked by the WST, which suggests neural correlates of abnormalities in conditional reasoning function in MD. These findings provide valuable insights into the understanding of the neural mechanisms of conditional reasoning function and may guide targeted interventions in patients with MD.

We thank the subjects and their families who participated in this study and we would like to acknowledge everyone who helped us in this project.

| 1. | Trivedi MH. Major Depressive Disorder in Primary Care: Strategies for Identification. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:UT17042BR1C. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Yang L, Guo C, Zheng Z, Dong Y, Xie Q, Lv Z, Li M, Lu Y, Guo X, Deng R, Liu Y, Feng Y, Mu R, Zhang X, Ma H, Chen Z, Zhang Z, Dong Z, Yang W, Zhang X, Cui Y. Stress dynamically modulates neuronal autophagy to gate depression onset. Nature. 2025;641:427-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, Pariante CM, Etkin A, Fava M, Mohr DC, Schatzberg AF. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1102] [Cited by in RCA: 1431] [Article Influence: 143.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Polosan M, Lemogne C, Jardri R, Fossati P. [Cognition - the core of major depressive disorder]. Encephale. 2016;42:1S3-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pan Z, Park C, Brietzke E, Zuckerman H, Rong C, Mansur RB, Fus D, Subramaniapillai M, Lee Y, McIntyre RS. Cognitive impairment in major depressive disorder. CNS Spectr. 2019;24:22-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang X, Wang M, Liao Q, Zhao L, Wei J, Wang Q, Sui J, Qi S, Ma X. Multiple cognition associated multimodal brain networks in major depressive disorder. Cereb Cortex. 2024;34:bhae305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beck AT. The evolution of the cognitive model of depression and its neurobiological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:969-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 864] [Cited by in RCA: 951] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kornreich C, Delle-Vigne D, Brevers D, Tecco J, Campanella S, Noël X, Verbanck P, Ermer E. Conditional Reasoning in Schizophrenic Patients. Evol Psychol. 2017;15:1474704917721713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu IM. Conditional reasoning and conditionalization. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2003;29:694-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cutmore TR, Halford GS, Wang Y, Ramm BJ, Spokes T, Shum DH. Neural correlates of deductive reasoning: An ERP study with the Wason Selection Task. Int J Psychophysiol. 2015;98:381-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li B, Zhang M, Luo J, Qiu J, Liu Y. The difference in spatiotemporal dynamics between modus ponens and modus tollens in the Wason selection task: an event-related potential study. Neuroscience. 2014;270:177-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fiddick L, Cosmides L, Tooby J. No interpretation without representation: the role of domain-specific representations and inferences in the Wason selection task. Cognition. 2000;77:1-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blanchette I, Richards A. The influence of affect on higher level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgement, decision making and reasoning. Cogn Emot. 2009;24:561-595. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Goel V, Dolan RJ. Explaining modulation of reasoning by belief. Cognition. 2003;87:B11-B22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Evans JS, Over DE, Manktelow KI. Reasoning, decision making and rationality. Cognition. 1993;49:165-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wason PC. Problem solving and reasoning. Br Med Bull. 1971;27:206-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ermer E, Guerin SA, Cosmides L, Tooby J, Miller MB. Theory of mind broad and narrow: reasoning about social exchange engages ToM areas, precautionary reasoning does not. Soc Neurosci. 2006;1:196-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kappenman ES, Farrens JL, Zhang W, Stewart AX, Luck SJ. ERP CORE: An open resource for human event-related potential research. Neuroimage. 2021;225:117465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Young D, Chelminski I, Dalrymple K. Severity classification on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. J Affect Disord. 2013;150:384-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 877] [Article Influence: 67.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tsuang HC, Chen WJ, Kuo SY, Hsiao PC. Handedness and schizotypy: The potential effect of changing the writing-hand. Psychiatry Res. 2016;242:198-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen C, Mei Q, Liu Q, Lu M, Hou L, Liu X, Gao X, Chen L, Zhou Z, Zhou H. Neural Correlates of Cognitive Dysfunction in Conditional Reasoning in Schizophrenia: An Event-related Potential Study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2024;20:571-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cai X, Li F, Wang Y, Jackson T, Chen J, Zhang L, Li H. Electrophysiological correlates of hypothesis evaluation: revealed with a modified Wason's selection task. Brain Res. 2011;1408:17-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Debener S, Ullsperger M, Siegel M, Fiehler K, von Cramon DY, Engel AK. Trial-by-trial coupling of concurrent electroencephalogram and functional magnetic resonance imaging identifies the dynamics of performance monitoring. J Neurosci. 2005;25:11730-11737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 748] [Cited by in RCA: 823] [Article Influence: 41.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Plöchl M, Ossandón JP, König P. Combining EEG and eye tracking: identification, characterization, and correction of eye movement artifacts in electroencephalographic data. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Koenig T, Stein M, Grieder M, Kottlow M. A tutorial on data-driven methods for statistically assessing ERP topographies. Brain Topogr. 2014;27:72-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Delorme A, Makeig S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. J Neurosci Methods. 2004;134:9-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13353] [Cited by in RCA: 16363] [Article Influence: 743.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brunet D, Murray MM, Michel CM. Spatiotemporal analysis of multichannel EEG: CARTOOL. Comput Intell Neurosci. 2011;2011:813870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 416] [Cited by in RCA: 536] [Article Influence: 35.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Poulsen AT, Pedroni A, Langer N, Hansen LK. Microstate EEGlab toolbox: An introductory guide. 2018 Preprint. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Murray MM, Brunet D, Michel CM. Topographic ERP analyses: a step-by-step tutorial review. Brain Topogr. 2008;20:249-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 715] [Cited by in RCA: 850] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Furukawa TA, Cipriani A, Cowen PJ, Leucht S, Egger M, Salanti G. Optimal dose of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, venlafaxine, and mirtazapine in major depression: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:601-609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Skovgaard-Olsen N. Ranking Theory and Conditional Reasoning. Cogn Sci. 2016;40:848-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wang L, Zhang M, Zou F, Wu X, Wang Y, Chen J. Brain Functional Networks Involved in Different Premise Order in Conditional Reasoning: A Dynamic Causal Model Study. J Cogn Neurosci. 2022;34:1416-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Markovits H, Thompson VA, Brisson J. Metacognition and abstract reasoning. Mem Cognit. 2015;43:681-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Evans JB, Twyman-Musgrove J. Conditional reasoning with inducements and advice. Cognition. 1998;69:B11-B16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Schwartz F, Epinat-Duclos J, Léone J, Prado J. The neural development of conditional reasoning in children: Different mechanisms for assessing the logical validity and likelihood of conclusions. Neuroimage. 2017;163:264-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hashemi SFS, Khosrowabadi R, Karimi M. Set-shifting and inhibition interplay affect the rule-matching bias occurrence during conditional reasoning task. J Med Life. 2022;15:828-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Blanchette I. The effect of emotion on interpretation and logic in a conditional reasoning task. Mem Cognit. 2006;34:1112-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wertheim J, Ragni M. The Neurocognitive Correlates of Human Reasoning: A Meta-analysis of Conditional and Syllogistic Inferences. J Cogn Neurosci. 2020;32:1061-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Almor A, Sloman SA. Reasoning versus text processing in the Wason selection task: a nondeontic perspective on perspective effects. Mem Cognit. 2000;28:1060-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Berthet V, Teovanović P, de Gardelle V. A common factor underlying individual differences in confirmation bias. Sci Rep. 2024;14:27795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Schupp HT, Flaisch T, Stockburger J, Junghöfer M. Emotion and attention: event-related brain potential studies. Prog Brain Res. 2006;156:31-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 673] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Elderkin-Thompson V, Kumar A, Bilker WB, Dunkin JJ, Mintz J, Moberg PJ, Mesholam RI, Gur RE. Neuropsychological deficits among patients with late-onset minor and major depression. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:529-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Krompinger JW, Simons RF. Cognitive inefficiency in depressive undergraduates: stroop processing and ERPs. Biol Psychol. 2011;86:239-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Cosmides L, Tooby J. Dissecting the computational architecture of social inference mechanisms. Ciba Found Symp. 1997;208:132-56; discussion 156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/