Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.110916

Revised: August 27, 2025

Accepted: October 10, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 121 Days and 1.6 Hours

Patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) experience not only progressive respiratory impairment but also a significant psychological burden. The prevalence and impact of anxiety and depression and their intricate relationship with dyspnea severity and pulmonary function decline remain inadequately characterized in this population, hindering comprehensive care.

To explore the incidence of anxiety and depression in CTD-ILD and its relation

Data of 100 patients with CTD-ILD (January 2022-June 2024) were retrospectively analyzed. Baseline demographic, pulmonary function [forced vital capacity (FVC%) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO%)], modified medical research council (mMRC) score, and psychological scale [gene

Baseline prevalence of moderate-to-severe anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) was 38% and 42%, respectively. Following 24 weeks of treatment, pulmonary function (FVC%: 72.11 ± 13.08 vs 67.89 ± 12.73; DLCO%: 60.67 ± 13.76 vs 55.32 ± 13.95, both P < 0.05), psychological scores (GAD-7 and PHQ-9, P < 0.05), and inflammatory markers [C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation, P < 0.05] signi

Anxiety and depression in patients with CTD-ILD constituted a bidirectional negative feedback loop involving pulmonary function impairment, inflammatory activity, and dyspnea. Psychological disorders were identified as independent risk factors for deterioration of pulmonary function. Psychological evaluation and intervention should be integrated clinically to block brain–lung axis-mediated neuroendocrine–immune network imbalance and improve prognosis.

Core Tip: This retrospective study investigates the association between anxiety, depression, dyspnea severity, and pulmonary function in patients with Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD). Results revealed that higher anxiety (generalized anxiety disorder-7) and depression (patient health questionnaire-9) scores were significantly correlated with worse pulmonary function (forced vital capacity, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide), more severe dyspnea (modified medical research council score), and elevated systemic inflammation (C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate). Moreover, psychological distress emerged as an independent predictor of pulmonary function decline. These findings underscore the importance of routine psychological assessment and timely intervention in CTD-ILD management to prevent deterioration and improve prognosis.

- Citation: Zhu ZJ, Liu KL, Qu HR. Relationship between anxiety and depression, dyspnea severity, and pulmonary function in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 110916

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/110916.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.110916

Connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease (CTD-ILD) is a chronic progressive disease, and its essence is that autoimmune connective tissue disease involves the lung parenchyma, triggering different alveolar inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis processes[1,2]. It is common in patients with systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus, and the extent of lung involvement can significantly affect survival rate and quality of life[3]. Patients with CTD-ILD often present with symptoms, such as dyspnea, chronic cough, and decreased activity tolerance. As the disease progresses, pulmonary function decreases significantly, especially forced vital capacity (FVC) and diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO), which have become important indicators of disease severity[4]. In addition to physical symptoms, psychological health concerns are increasing in patients with CTD-ILD are a growing concern. Anxiety and depression, which are common psychological disorders, are more prevalent in patients with chronic respiratory diseases than in the general population[5]. Chronic diseases, such as physical pain, limited activity, uncertainty regarding the future, and drug side effects, may induce anxiety and depression, which in turn affect treatment compliance and quality of life[6]. However, systematic studies on the relationship between anxiety and depression and their clinical characteristics in patients with CTD-ILD are scarce, and the correlation between the subjective dyspnea score and objective indicators of pulmonary function remain unclear[7]. This study aimed to investigate the incidence of anxiety and depression in patients with CTD-ILD and analyze their relationship with the severity of dyspnea and pulmonary function parameters to elucidate the interaction mechanism between physiology and psychology, and to provide the basis for formulating more comprehensive clinical intervention strategies. This has important clinical value for improving the overall health management and prognosis of patients.

This retrospective cohort study enrolled patients diagnosed with CTD-ILD who visited the respiratory department of Longhua Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine from January 2022 to June 2024. A total of 100 patients were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Age of 18-75 years; (2) Diagnosis of CTD-ILD through clinical examination, imaging examination [chest computed tomography (CT)], pulmonary function test, and pathological examination (bronchoscopy or open lung biopsy), and had known connective tissue diseases (systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus); (3) Symptoms of dyspnea [assessed using the modified medical research council (mMRC) score] or cough lasting at least 3 months; (4) FVC ≥ 40% predicted value and DLCO ≥ 30% predicted value to ensure that patients can receive relevant pulmonary function evaluation; and (5) Evaluated using the standardized generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) and patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) at the time of enrollment. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Severe cardiovascular disease, malignant tumor, or other irreversible organ failure; (2) CTD-ILD in the acute exacerbation phase (defined as significant tachypnea, increased cough, or increased body temperature within the last 2 weeks); (3) Severe psychological disorders, such as schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder, or an inability to complete the anxiety and depression scale evaluation for psychological reasons; and (4) Failure to complete a complete pulmonary function test or assessment of anxiety and depression scale, or failure to provide sufficient clinical data were excluded from the study. All the enrolled patients signed an informed consent form, and the study procedure was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee.

All enrolled patients received standardized individualized treatment according to the diagnosis and treatment guidelines for interstitial lung disease of the China Respiratory Society and a consensus on the management of connective tissue disease. Basic treatment included glucocorticoids combined with immunosuppressive agents, supplementation with anti-fibrotic therapy, and oxygen therapy support when necessary. Glucocorticoid treatment involved prednisone (Prednisone, Pfizer Pharmaceutical Co.), which is the first-line agent recommended by the treatment guidelines for its potent anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive effects. The initial dose was 0.5 mg/kg/day, oral administered once daily. After 6-12 weeks of treatment, the dose was gradually reduced to a maintenance dose of 5-10 mg/day according to the clinical response. Mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept, Roche Co., Ltd.) was preferentially used as an immunosuppressive agent because of its established efficacy and favorable safety profile in patients with CTD-ILD at a dose of 1.0 g, orally administered twice daily. Alternatively, tacrolimus (Prograf, Astellas Co.) was used at 0.1-0.15 mg/kg/day in two divided doses, particularly for patients who may benefit from calcineurin inhibition or are intolerant to other agents. Some patients with poor tolerance or abnormal renal function were switched to cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan, Baxter Co.) for intravenous infusion at a dose of 600 mg/m2, once every 4 weeks, and the efficacy was evaluated after six treatment courses. For patients with imaging findings suggestive of progressive pulmonary fibrosis and continuous decline in pulmonary function (annual decline of FVC > 10%), the anti-fibrosis drug nintedanib (Ofev, Boehringer Ingelheim) was used at a dose of 100 mg orally twice daily after meals, or pirfenidone (Escrow, Shanghai Fosun Medicine) as a combined regimen. As for adjuvant therapy, all patients received regular lung rehabilitation guidance and oxygen therapy evaluation. High-flow oxygen therapy support was provided with oxygen flow controlled at 2-5 L/min, adjusted according to oxygen saturation. All treatment procedures were evaluated by specialists, and the efficacy and adverse reactions were recorded to ensure safety and compliance with the protocol.

Two trained respiratory residents uniformly collected baseline data for all enrolled patients when they were enrolled in the group, to ensure the accuracy and consistency of the data. The baseline data were divided into five dimensions: General demographic information, clinical history, pulmonary function parameters, dyspnea score, and psychological evaluation: (1) The general demographic information including sex, age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), smoking history (smoking status, smoking duration, and daily smoking volume), and occupational exposure history; (2) Regarding clinical history and laboratory indicators, the types of underlying diseases (such as systemic sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis), disease course, medication history, and autoimmune antibody spectrum were recorded along with laboratory results, such as routine blood tests, liver and kidney function, electrolytes, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP). Blood samples were collected from empty stomachs on the morning of admission. A Hitachi 7600 automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation, Hitachi, Ltd.) was used at the hospital’s clinical laboratory; (3) For pulmonary function parameters, all patients were tested for pulmonary function during the stable phase, including FVC, forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), FEV1/FVC ratio, and DLCO. Testing was performed using a Master Screen PFT system (model: Vmax Encore) manufactured by CareFusion, United States, and quality control was performed according to the ATS/ERS standard; (4) The mMRC was used to assess the degree of dyspnea, with scores ranging from 0 (no breathlessness except with strenuous exercise) to 4 (too breathless to leave the house or breathless when dressing or undressing). A score ≥ 1 is generally considered to indicate clinically significant dyspnea that impacts daily life; and (5) The GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms. All scales were completed by patients after obtaining informed consent. The physicians supervised and explained the scoring process to ensure accurate understanding.

All data were recorded in a uniformly designed electronic data acquisition table that was regularly checked and cleaned by the data administrator to ensure the scientificity and repeatability of the subsequent statistical analyses.

The pulmonary function test included: FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and DLCO. All tests were performed under stable conditions. The first test was completed on the day of enrollment and was repeated every 3 months until the study endpoint. Before the test, the patients were guided by a professional technician to conduct at least two rehearsal exercises to ensure operating standards. Three expiratory waveforms with good repeatability were selected as the final results.

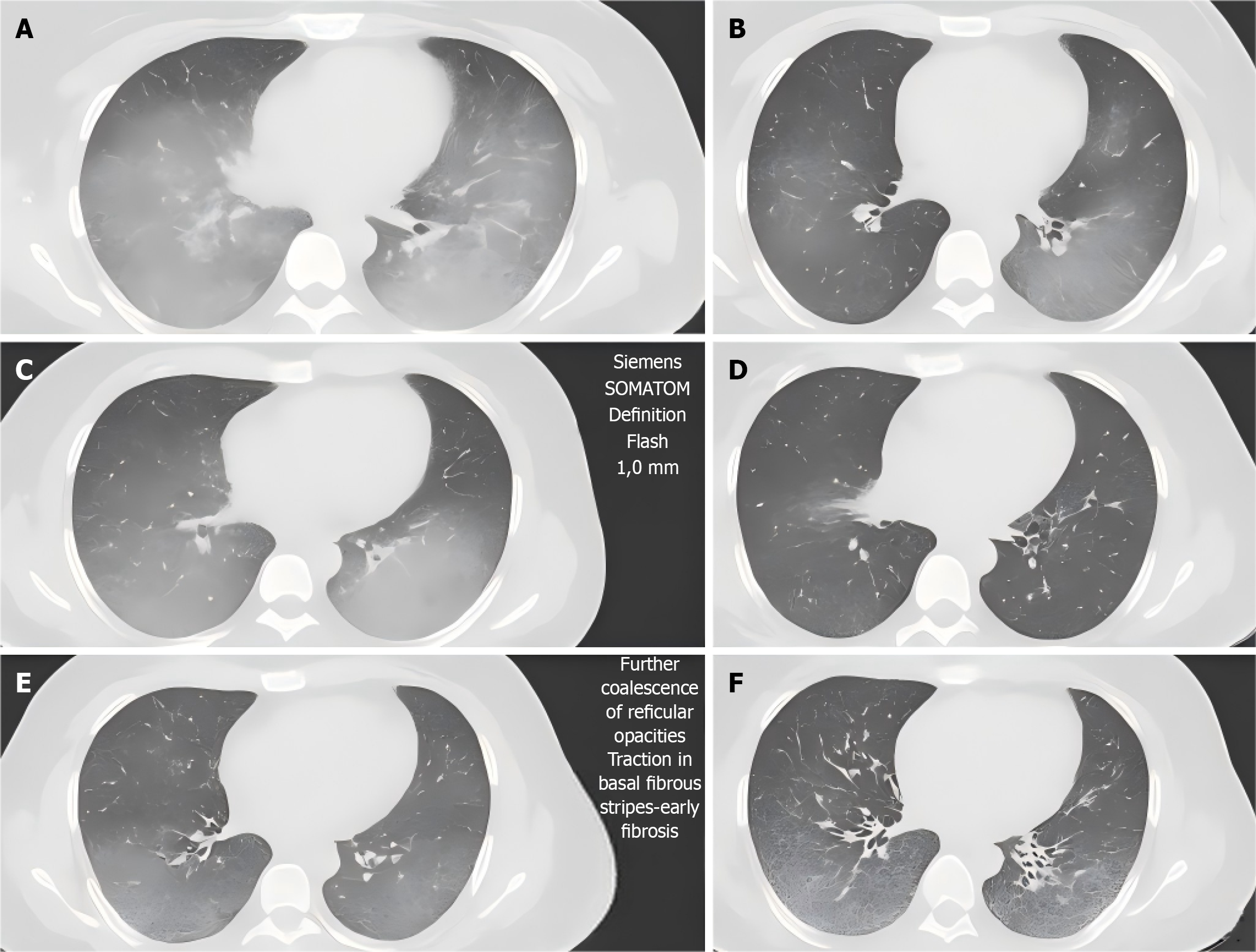

High-resolution CT of the lungs: High-resolution CT (HRCT) was used to evaluate the lungs. The initial examination was completed when the patients were enrolled, and re-examination was performed every 6 months to evaluate the extent of lung parenchyma involvement and fibrosis progression. The images were acquired using a SOMATOM Definition Flash CT machine (Siemens, Germany) with a layer thickness of 1.0 mm, tube voltage of 120 kVp, and tube current of 200-250 mAs. The images were independently viewed by two senior imaging physicians and the scope of the pulmonary interstitial lesions was evaluated using a quantitative scoring system.

Serological index test: Venous blood (5 mL) was collected from all patients in the early morning under fasting conditions at the time of admission and at the 4th, 12th and 24th week of treatment. Detection indicators included the inflammatory indicators CRP and ESR, immunological indicators antinuclear antibody (ANA), extractable nuclear antibody (ENA), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody (anti-CCP), liver and kidney function, electrolytes, and routine blood tests. The samples were analyzed using a Hitachi 7600 series automatic biochemical analyzer and a Roche Cobas e411 electrochemical luminescence immunoassay analyzer at the Department of Clinical Laboratory of the Hospital. CRP was determined using Roche reagents within 0.1-350 mg/L; ESR was measured using the standard Westergren method: A graduated pipette was filled with 0.4 mL of sodium citrate solution and 1.6 mL of venous blood, followed by vertical standing at room temperature for 1 hour, after which the distance (in mm) from the top of the plasma to the top of the settled red blood cell column was recorded; The ANA spectrum was determined by immunoblotting (EUROIMMUN Kit).

Psychological evaluation method: The anxiety and depression states of the patients were evaluated using the GAD-7 and PHQ-9. The scores of the two questionnaires were seven items, with 0-21 points (GAD-7) and 0-27 points (PHQ-9) for each item. The evaluation time node was synchronized with the serum test, completed once at enrollment and once at weeks 4, 12, and 24. The patients completed the scale under the guidance of a physician. If any difficulty in under

Detection of oxygenation function: During each outpatient re-examination, resting percutaneous oxygen saturation (SpO2), partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) for arterial blood gas analysis, and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) were measured. The SpO2 measurement was performed using a pulse oximeter finger clip. A blood gas analyzer was used for arterial blood gas analysis. Experienced nurses collected blood samples from the radial artery. The samples were sent for examination within 5 minutes.

The pulmonary function indices included: FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC ratio, and DLCO. FVC and DLCO are expressed as percentages of the predicted values (%). If the decrease in FVC was > 10% or the decrease in DLCO was > 15%, function was judged to have deteriorated. Increases of FVC ≥ 10% and DLCO ≥ 15% were considered significant improvements. Pulmonary function was tested every 3 months using a Jeger Master Screen Diffusion combination pulmonary function analyzer (Jeger, Germany).

HRCT imaging indicators: A Siemens SOMATOM Definition Flash HRCT machine was used to evaluate the scope of the pulmonary interstitial lesions and progression of fibrosis. The involved area of each lung lobe was graded by two imaging physicians using a quantitative scoring system. The progression of the imaging was determined as an increase in the lesion area of ≥ 10%, which was reviewed once every 6 months.

Serological indicators: Inflammation- (CRP and ESR) and immunology-related indicators (ANA, ENA, RF, and anti-CCP) were detected. CRP ≥ 10 mg/L and ESR ≥ 30 mm/h suggested active systemic inflammation. The test frequency was at enrollment and at the 4th, 12th and 24th week.

GAD-7 and PHQ-9 were used to assess anxiety and depressive symptoms: GAD-7 ≥ 10 points and PHQ-9 ≥ 10 points respectively represented moderate and severe anxiety and depression, respectively, and further psychological interven

Oxygenation function was indicated by resting SpO2, arterial PaO2, and PaCO2 levels: An SpO2 < 90% or PaO2 < 60 mmHg suggested hypoxemia, and frequency was detected at every outpatient re-examination.

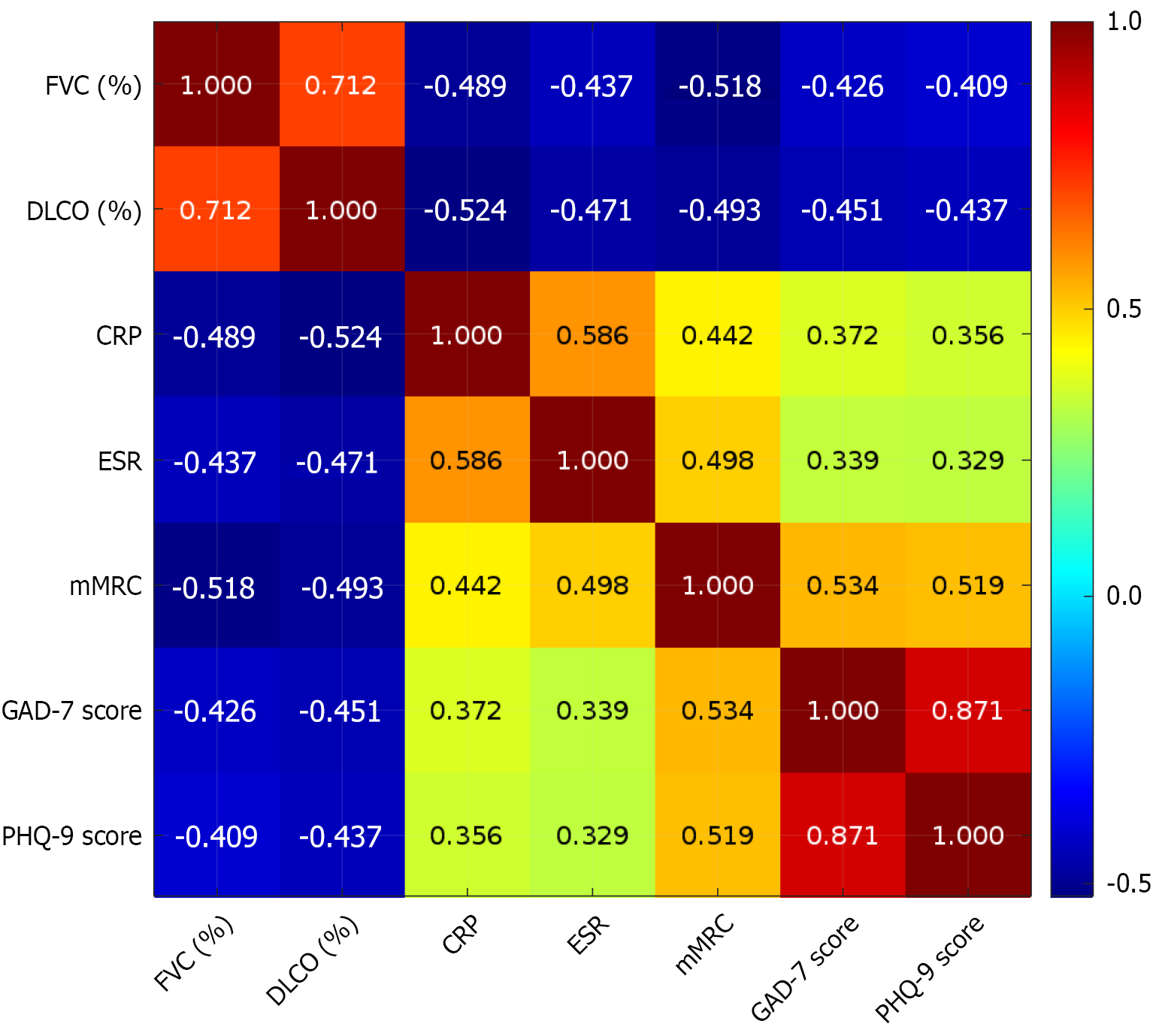

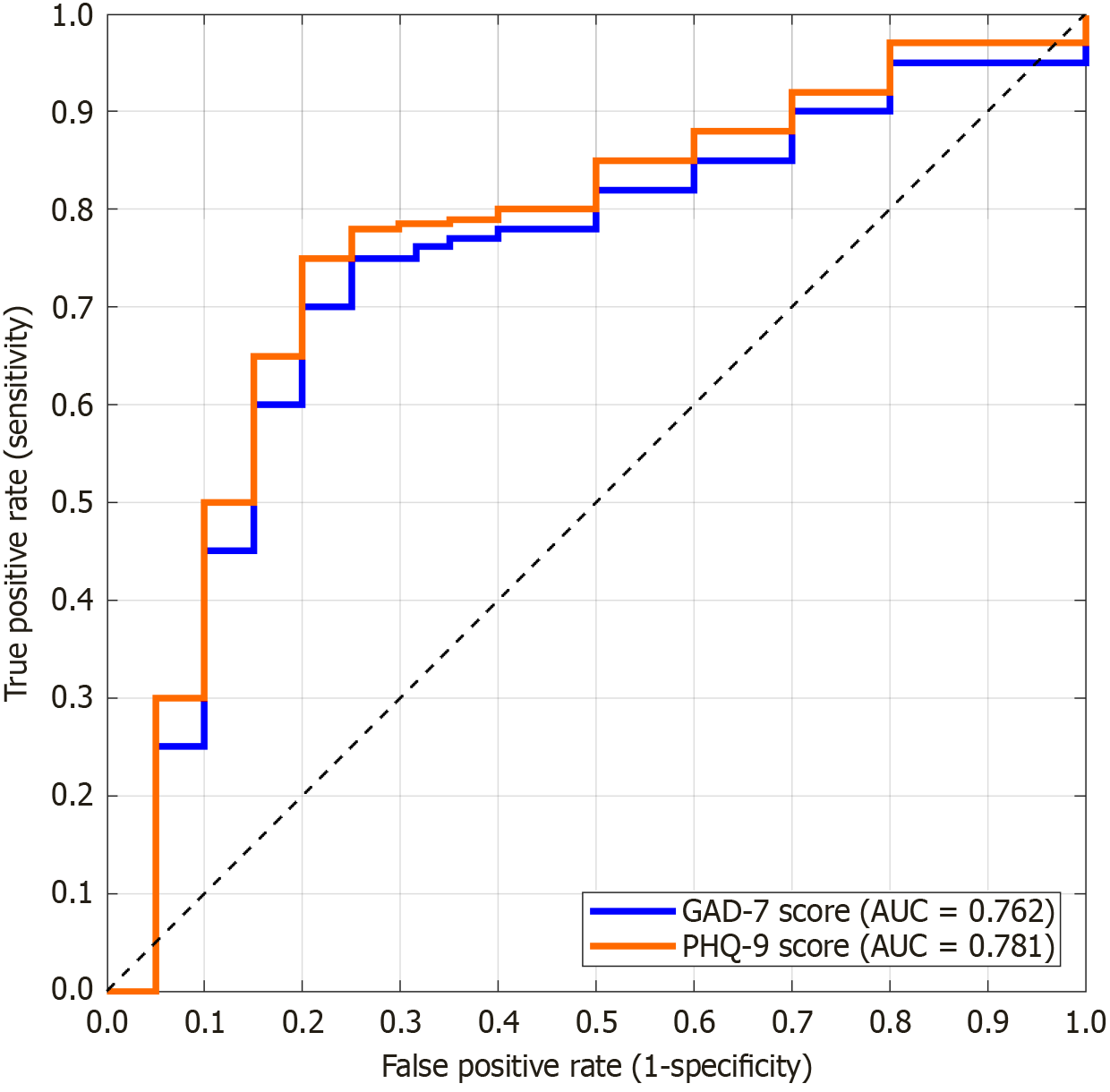

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD, enumeration data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and intra-group comparisons were performed using t-test and χ2 test. An independent sample t-test or analysis of variance was used for comparisons between groups. Non-normally distributed data are expressed as medians (quartiles) [M (P25, P75)], and inter-group comparisons were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis H test. Pearson or Spearman correlation analysis was performed to analyze the correlation between anxiety (GAD-7 score), depression (PHQ-9 score), and continuous variables, such as pulmonary function (FVC% and DLCO%), inflammation indices (CRP and ESR), and dyspnea score (mMRC). A linear mixed-effects model was used to evaluate the longitudinal relationship between the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores and pulmonary function indicators over time. In the model, patient ID was set as a random effect, time and evaluation indicators as fixed effects, and confounding factors, such as age, sex, and type of underlying disease were controlled. To assess the effects of anxiety and depression on disease progression, a Cox proportional hazard regression model was used in which the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were used as time-varying covariates. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) between the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores and pulmonary function deterioration or HRCT imaging progression were observed. Receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was used to assess the differential ability of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 in predicting pulmonary function deterioration (FVC decline ≥ 10%), and the area under the curve (AUC) as well as its sensitivity and specificity were calculated to determine the optimal cutoff value. All statistical tests were performed bilaterally, and significance was set at P < 0.05.

The general characteristics of the enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. Compared with population norms or clinical thresholds, the baseline levels of CRP, ESR, mMRC, GAD-7, and PHQ-9 were notably elevated, whereas FVC% and DLCO% were significantly impaired (all P < 0.05). No significant differences in age, BMI, smoking history, or FEV1 were observed between the study cohort and expected demographics (P > 0.05). Thus, pulmonary function and psychological state were significantly abnormal, and early intervention and comprehensive evaluation should be strengthened.

| Indicators | Data | χ2/t | P value |

| Age (years) | 59.24 ± 10.51 | 1.733 | 0.086 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.67 ± 3.18 | 1.294 | 0.199 |

| Smoking history | |||

| Yes | 42 | 2.763 | 0.096 |

| No | 58 | ||

| Systemic sclerosis (n) | 40 | - | - |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.25 ± 6.34 | 2.184 | 0.031 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 29.17 ± 12.58 | 2.659 | 0.009 |

| FVC (%) | 67.89 ± 12.73 | 3.502 | 0.001 |

| DLCO (%) | 55.32 ± 13.95 | 3.761 | < 0.001 |

| mMRC (points) | 1.87 ± 0.98 | 2.816 | 0.006 |

| GAD-7 (points) | 7.14 ± 4.03 | 3.945 | < 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 (points) | 8.76 ± 4.85 | 4.118 | < 0.001 |

The test results of the pulmonary function indicators at different time points showed that the FVC, DLCO, and FEV1 of the patients significantly improved to different degrees (P < 0.05). The change in FEV1-FVC ratio was not statistically significant (P = 0.112) (Table 2).

| Indicators | At enrollment | Week 12 | Week 24 | F value | P value |

| FVC (%) | 67.89 ± 12.73 | 70.48 ± 12.29 | 72.11 ± 13.08 | 8.742 | 0.001 |

| DLCO (%) | 55.32 ± 13.95 | 58.21 ± 14.10 | 60.67 ± 13.76 | 9.315 | < 0.001 |

| FEV1 (L) | 1.81 ± 0.49 | 1.89 ± 0.51 | 1.93 ± 0.52 | 5.462 | 0.01 |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 66.89 ± 7.41 | 67.35 ± 7.29 | 68.14 ± 7.25 | 2.374 | 0.112 |

The HRCT imaging scores gradually decreased over time, and the number of patients with imaging progress was significantly reduced. The difference between the groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001) (Table 3; Figure 1), suggesting that the lesion range significantly improved with follow-up time.

| Indicators | At enrollment | Week 12 | Week 24 | χ2/t | P value |

| HRCT lesion score (%) | 32.74 ± 10.29 | 29.65 ± 9.87 | 27.53 ± 9.34 | 7.813 | 0.001 |

| Number of imaging progresses (n) | 34 | 24 | 18 | 6.231 | 0.044 |

CRP and ESR significantly decreased during treatment, suggesting that the inflammatory reaction was significantly relieved (P < 0.05). The increases in SpO2 and PaO2 were highly significant (P < 0.001 for both). The changes in the positive rates of ANA, ENA, RF, and anti-CCP in the immunological indices were not significant (P > 0.05) (Table 4), indicating a stable autoimmune state.

| Indicators | At enrollment | Week 4 | Week 12 | Week 24 | χ2/t | P value |

| CRP (mg/L) | 11.25 ± 6.34 | 8.12 ± 4.27 | 6.45 ± 3.89 | 5.87 ± 3.12 | 8.423 | < 0.001 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 29.17 ± 12.58 | 22.84 ± 10.76 | 18.32 ± 9.65 | 15.42 ± 9.73 | 7.125 | < 0.001 |

| ANA positive rate (%) | 48 | 46 | 45 | 44 | 1.042 | 0.307 |

| ENA positive rate (%) | 32 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 0.789 | 0.446 |

| RF positive rate (%) | 35 | 33 | 32 | 31 | 0.654 | 0.521 |

| Anti-CCP positive rate (%) | 28 | 27 | 26 | 26 | 0.413 | 0.675 |

The GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores of the patients decreased significantly with treatment time, and anxiety and depressive symptoms were gradually alleviated (P < 0.05). The numbers of patients with moderate or above anxiety (GAD-7 ≥ 10) and depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) (Table 5), indicating a significant improvement in psychological status.

| Indicators | At enrollment | Week 4 | Week 12 | Week 24 | F value | P value |

| GAD-7 (points) | 7.14 ± 4.03 | 6.02 ± 3.58 | 5.23 ± 3.22 | 4.89 ± 3.11 | 12.753 | < 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 (points) | 8.76 ± 4.85 | 6.98 ± 4.41 | 5.84 ± 3.93 | 5.12 ± 3.67 | 14.189 | < 0.001 |

| GAD-7 ≥ 10 (n) | 38 | 28 | 22 | 19 | 8.429 | 0.038 |

| PHQ-9 ≥ 10 (n) | 42 | 31 | 25 | 21 | 7.165 | 0.047 |

The resting SpO2 and PaO2 of the patients significantly increased during treatment. No significant change in PaCO2 was observed, and the number of hypoxemia cases was significantly reduced, suggesting significant improvement of oxyge

| Indicators | At enrollment | Week 4 | Week 12 | Week 24 | F value | P value |

| SpO2 (%) | 88.74 ± 5.13 | 90.32 ± 4.88 | 91.45 ± 4.59 | 92.13 ± 4.21 | 15.238 | < 0.001 |

| PaO2 (mmHg) | 58.96 ± 8.27 | 62.87 ± 7.56 | 65.23 ± 7.11 | 67.45 ± 6.85 | 18.427 | < 0.001 |

| PaCO2 (mmHg) | 40.15 ± 5.42 | 39.82 ± 5.16 | 39.58 ± 5.21 | 39.34 ± 5.10 | 1.254 | 0.292 |

| Hypoxemia cases | 35 | 28 | 22 | 17 | 8.013 | 0.045 |

Anxiety (GAD-7) and depression (PHQ-9) were negatively correlated with pulmonary function (FVC% and DLCO%) and positively correlated with inflammation indices (CRP and ESR) and the dyspnea score (mMRC), with a statistically significant correlation (P < 0.05) (Table 7; Figure 2).

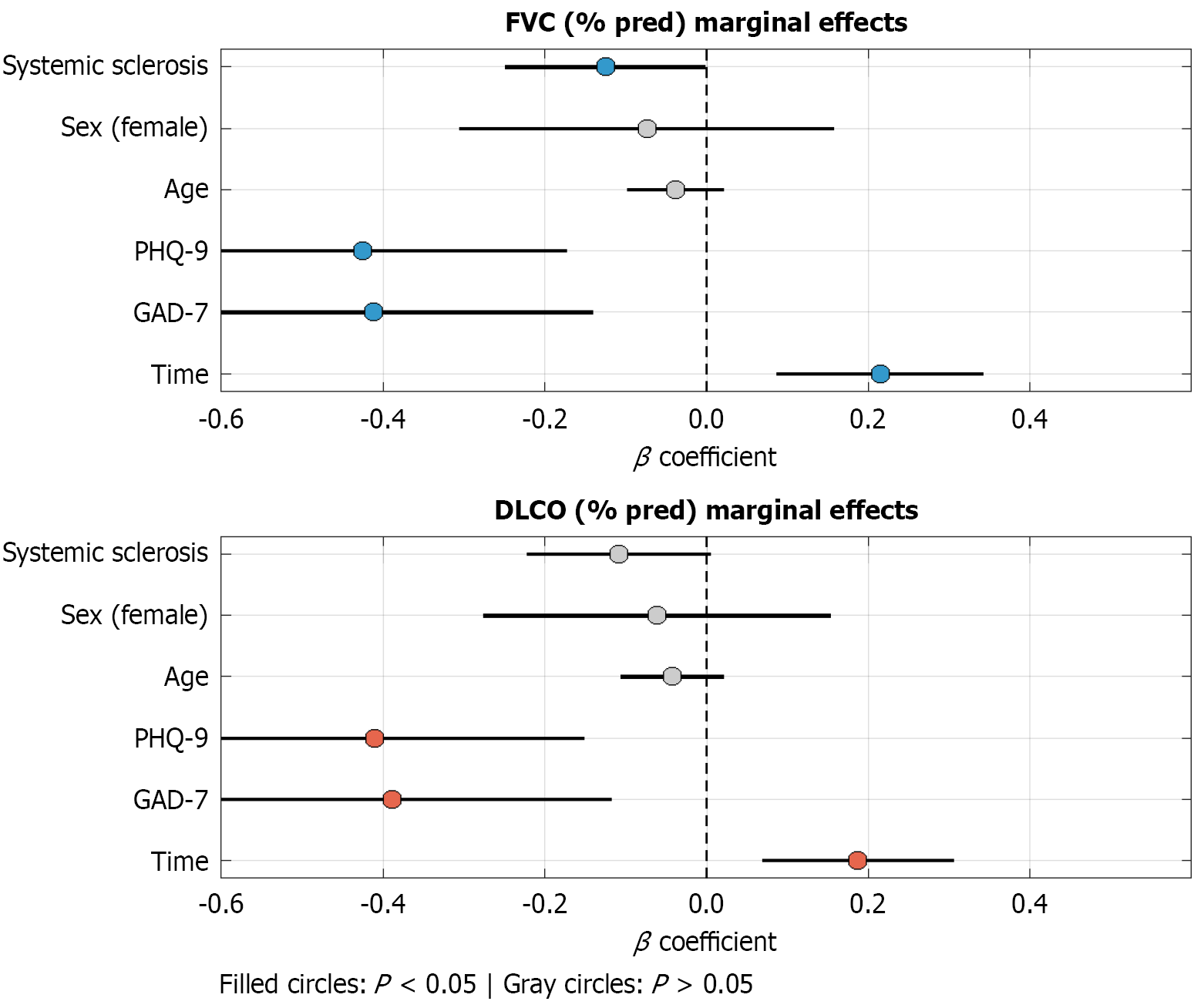

The results of the mixed-effects model showed that the time variables significantly influenced the improvement of FVC and DLCO (P < 0.05), whereas the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores were significantly and negatively correlated with pulmonary function (P < 0.05) (Table 8; Figure 3). Thus, anxiety and depression might have an adverse effect on the recovery of pulmonary function.

| Fixed effect variable | FVC% (β) | FVC% (P) | DLCO% (β) | DLCO% (P) |

| Time | 0.215 | < 0.001 | 0.187 | 0.002 |

| GAD-7 | -0.412 | 0.003 | -0.389 | 0.005 |

| PHQ-9 | -0.426 | 0.001 | -0.411 | 0.002 |

| Age | -0.038 | 0.217 | -0.042 | 0.198 |

| Sex (female = 1) | -0.074 | 0.532 | -0.061 | 0.578 |

| Systemic sclerosis (yes = 1) | -0.125 | 0.048 | -0.109 | 0.061 |

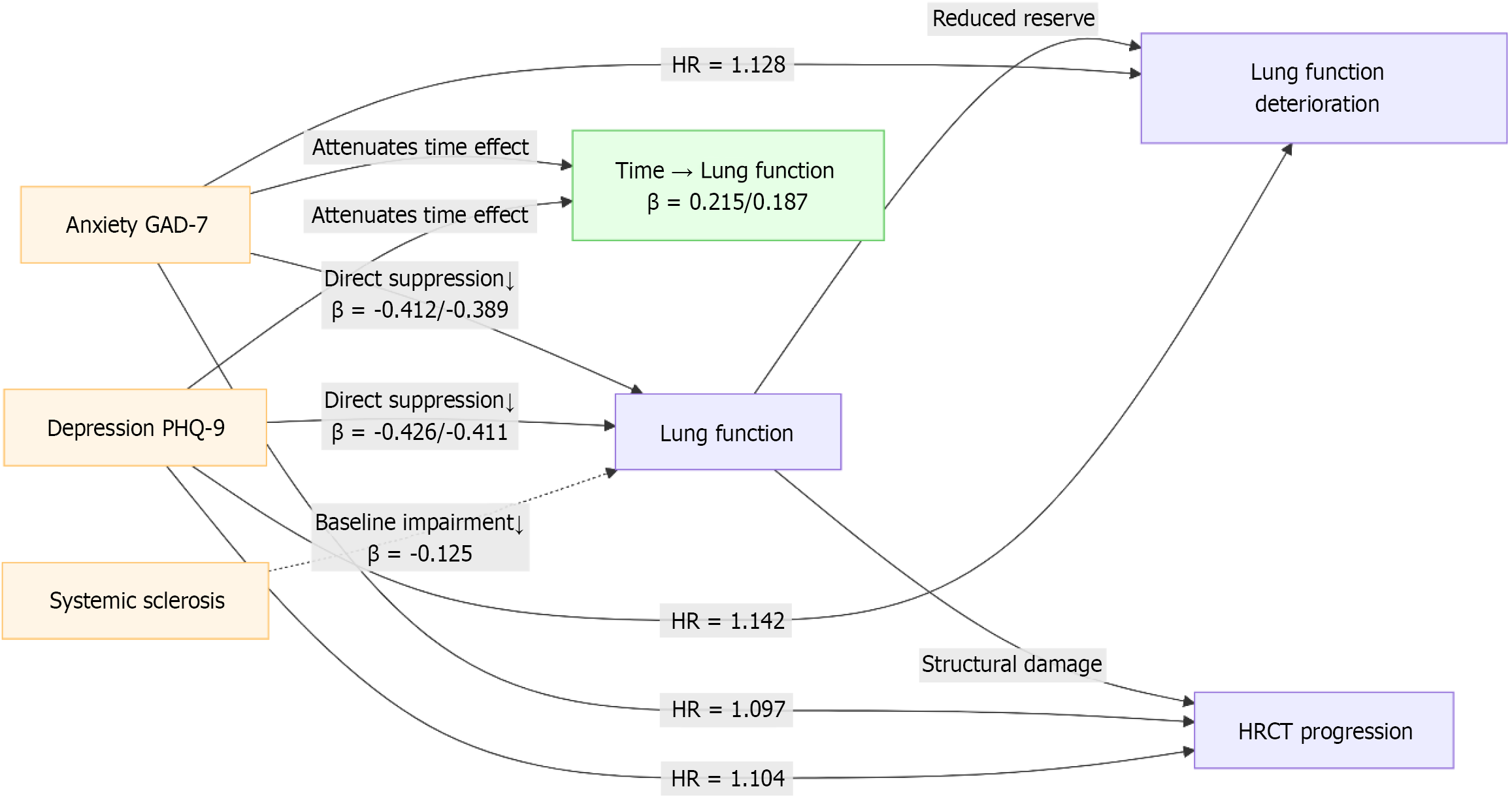

Increased GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores significantly increased the risk of pulmonary function deterioration and progression on HRCT imaging (P < 0.05). However, age, sex, and systemic sclerosis had no significant effect on disease progression (P > 0.05) (Table 9). Combined with the 3.8 mixed-effect model and Cox regression results, the higher the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, the smaller the improvement in pulmonary function, and the risk of pulmonary function deterioration and HRCT progression was significantly increased (P < 0.05), suggesting that anxiety and depression might interfere with the pulmonary rehabilitation process by affecting physiological regulation and the disease progression pathway (Figure 4).

| Variable | Deterioration of pulmonary function HR (95%CI) | P value | HRCT progression HR (95%CI) | P value |

| GAD-7 (time-varying) | 1.128 (1.042-1.221) | 0.003 | 1.097 (1.015-1.186) | 0.019 |

| PHQ-9 (time-varying) | 1.142 (1.053-1.238) | 0.002 | 1.104 (1.017-1.198) | 0.018 |

| Age (years) | 1.008 (0.976-1.041) | 0.611 | 1.012 (0.982-1.043) | 0.43 |

| Sex (female = 1) | 1.152 (0.752-1.764) | 0.511 | 1.091 (0.698-1.707) | 0.705 |

| Systemic sclerosis (yes = 1) | 1.324 (0.884-1.984) | 0.176 | 1.287 (0.859-1.928) | 0.221 |

The results of the Cox regression analysis are presented in Table 9. Elevated GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores, treated as time-varying covariates, were significantly associated with an increased risk of pulmonary function deterioration (GAD-7: HR = 1.128, 95%CI: 1.042-1.221, P = 0.003; PHQ-9: HR = 1.142, 95%CI: 1.053-1.238, P = 0.002) and HRCT progression (GAD-7: HR = 1.097, 95%CI: 1.015-1.186, P = 0.019; PHQ-9: HR = 1.104, 95%CI: 1.017-1.198, P = 0.018) (Table 10; Figure 5), suggesting that anxiety and depression might adversely affect the recovery of pulmonary function.

| Indicators | Cut-off value | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC | 95%CI | Youden's index |

| GAD-7 | 7.5 | 76.2 | 68.4 | 0.762 | 0.675-0.849 | 0.446 |

| PHQ-9 | 8 | 78.6 | 70.2 | 0.781 | 0.698-0.865 | 0.487 |

This study systematically explored the interactions between anxiety and depression, dyspnea, and pulmonary function in patients with CTD-ILD and constructed a complete evidence chain from symptom assessment, function detection, and mechanism exploration. A high prevalence of clinically significant anxiety and depression was observed in patients with CTD-ILD (38% with GAD-7 ≥ 10 points and 42% with PHQ-9 ≥ 10 points, thresholds commonly indicating moderate-to-severe symptoms requiring intervention) and significantly correlated with pulmonary function impairment (FVC% and DLCO%), inflammatory activity (CRP and ESR), and subjective dyspnea (mMRC). Longitudinal analysis further con

The correlation patterns observed in this study support the potential role of the “brain-lung axis” in CTD-ILD, although mechanistic insights are limited by the lack of specific biomarker data, and the interaction pathways can be summarized into three categories: Anxiety and depression accompanied by HPA axis hyperfunction and cortisol rhythm disorder. In this study, the psychological score of the systemic sclerosis subgroup (40%) had a more significant effect on pulmonary function, which might be attributable to the autonomic neuropathy unique to the disease: Increased sympathetic tone, which activated lung fibroblasts and promoted collagen deposition through β2 adrenergic receptor[17]. Simultaneously, cortisol resistance weakens the anti-fibrotic effect of glucocorticoids, which is consistent with the rapid progression of fibrous bands in the basal segment of HRCT[18]. Psychological stress magnifies the pulmonary inflammatory response by releasing catecholamines, stimulating bone marrow to release immature granulocytes, and enhancing the expression of Toll-like receptor[19]. Anxiety and depression scores changed synchronously with CRP/ESR, and psychological state significantly improved after inflammation was relieved (Tables 4 and 5). This explains why combined immunosuppressive therapy (such as cyclophosphamide) can not only control pulmonary interstitial lesions but also indirectly relieve anxiety symptoms[20]. Patients with anxiety often present with “hyperventilation syndrome”, which leads to respiratory muscle fatigue and abnormal fluctuations in the partial pressure of carbon dioxide. Although no statistically significant change in PaCO2 was observed in this study (Table 6), high GAD-7 scores demonstrated more significant SpO2 fluctuations, which might be caused by a respiratory pattern disorder[21]. Depression-induced decreased adherence to treatment (such as missed pirfenidone) also indirectly affected the efficacy, as evidenced by the lower improvement in pulmonary function in the PHQ-9 ≥ 10 subgroup[22]. In this study, the ROC curve confirmed the critical values of psychological screening (GAD-7 ≥ 7.5 and PHQ-9 ≥ 8), and its AUC for predicting pulmonary function deterioration ranged from 0.762 to 0.781. Thus, psychological evaluation should be included in the routine follow-up of CTD-ILD to facilitate early identification of high-risk populations. For patients reaching this standard, in addition to optimi

This study has some limitations. First, owing to the single-center retrospective design (n = 100), this study failed to distinguish the subtypes of connective tissue disease for hierarchical analysis, which might affect the universality of conclusions. Second, lack of monitoring of dynamic neuroendocrine indicators (such as cortisol and catecholamine) and specific pro-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-6 and TNF-α) limited the in-depth interpretation of the “brain-lung axis” mechanism and a more comprehensive assessment of systemic inflammation. Lastly, no psychological intervention controlled trial was established to verify the direct effect of improving anxiety and depression on delaying pulmonary fibrosis. Future multicenter prospective large-sample cohort studies are required to refine the disease subtype analysis. The neuroimmune interaction pathway is quantified by combining multi-omics techniques (serum inflammatory factor spectrum, brain imaging, etc.). We also evaluated the impact of comprehensive treatment regimens that integrated psychological intervention on the prognosis of pulmonary function through randomized controlled trials.

The study findings confirmed that anxiety and depression in patients with CTD-ILD constitute a two-way negative feedback loop with pulmonary function impairment, inflammatory activity, and subjective dyspnea, whose core mechanism is the imbalance of neuroendocrine-immune network regulated by the “brain–lung axis”. Psychological disorders are not only a manifestation of disease burden, but also an independent risk factor for the progression of pulmonary fibrosis. Therefore, clinical management needs to expand from the traditional organ-centered model and establish a comprehensive intervention strategy of “treating both the heart and lungs and healing both the body and mind”. Through early psychological screening, targeted drugs, and behavioral interventions, the vicious circle of psychosomatic interaction is blocked, and the long-term prognosis of patients is improved.

| 1. | Spagnolo P, Distler O, Ryerson CJ, Tzouvelekis A, Lee JS, Bonella F, Bouros D, Hoffmann-Vold AM, Crestani B, Matteson EL. Mechanisms of progressive fibrosis in connective tissue disease (CTD)-associated interstitial lung diseases (ILDs). Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:143-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maher TM, Tudor VA, Saunders P, Gibbons MA, Fletcher SV, Denton CP, Hoyles RK, Parfrey H, Renzoni EA, Kokosi M, Wells AU, Ashby D, Szigeti M, Molyneaux PL; RECITAL Investigators. Rituximab versus intravenous cyclophosphamide in patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease in the UK (RECITAL): a double-blind, double-dummy, randomised, controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2023;11:45-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 222] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shao T, Shi X, Yang S, Zhang W, Li X, Shu J, Alqalyoobi S, Zeki AA, Leung PS, Shuai Z. Interstitial Lung Disease in Connective Tissue Disease: A Common Lesion With Heterogeneous Mechanisms and Treatment Considerations. Front Immunol. 2021;12:684699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kondoh Y, Bando M, Kawahito Y, Sato S, Suda T, Kuwana M. Identification and management of interstitial lung disease associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc-ILD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA-ILD), and polymyositis/dermatomyositis (PM/DM-ILD): development of expert consensus-based clinical algorithms. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2024;18:447-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ding F, Wang Z, Wang J, Ma Y, Jin J. Serum S1P level in interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a potential biomarker reflecting the severity of pulmonary function. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24:266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guiot J, Miedema J, Cordeiro A, De Vries-Bouwstra JK, Dimitroulas T, Søndergaard K, Tzouvelekis A, Smith V. Practical guidance for the early recognition and follow-up of patients with connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2024;23:103582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boutel M, Boutou A, Pitsiou G, Garyfallos A, Dimitroulas T. Efficacy and Safety of Nintedanib in Patients with Connective Tissue Disease-Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD): A Real-World Single Center Experience. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Buschulte K, Kabitz HJ, Hagmeyer L, Hammerl P, Esselmann A, Wiederhold C, Skowasch D, Stolpe C, Joest M, Veitshans S, Höffgen M, Maqhuzu P, Schwarzkopf L, Hellmann A, Pfeifer M, Behr J, Karpavicius R, Günther A, Polke M, Höger P, Somogyi V, Lederer C, Markart P, Kreuter M. Disease trajectories in interstitial lung diseases - data from the EXCITING-ILD registry. Respir Res. 2024;25:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miądlikowska E, Miłkowska-Dymanowska J, Białas AJ, Makowska JS, Lewandowska-Polak A, Puła A, Kumor-Kisielewska A, Piotrowski WJ. Serum KL-6 and SP-D: Markers of Lung Function in Autoimmune-Related Interstitial Lung Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ba C, Jiang C, Wang H, Shi X, Jin J, Fang Q. Prognostic value of serum oncomarkers for patients hospitalized with acute exacerbation of interstitial lung disease. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2024;18:17534666241250332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee JK, Ahn Y, Noh HN, Lee SM, Yoo B, Lee CK, Kim YG, Hong S, Ahn SM, Kim HC. Clinical effect of progressive pulmonary fibrosis on patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: a single center retrospective cohort study. Clin Exp Med. 2023;23:4797-4807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bernardinello N, Cocconcelli E, Boscolo A, Castelli G, Sella N, Giraudo C, Zanatta E, Rea F, Saetta M, Navalesi P, Spagnolo P, Balestro E. Prevalence of diaphragm dysfunction in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD): The role of diaphragmatic ultrasound. Respir Med. 2023;216:107293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liang Z, Long F, Deng K, Wang F, Xiao J, Yang Y, Zhang D, Gu W, Xu J, Jian W, Shi W, Zheng J, Chen X, Gao Y, Luo Q, Stampfli MR, Peng T, Chen R. Dissociation between airway and systemic autoantibody responses in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Álvarez Troncoso J, Porto Fuentes Ó, Fernández Velilla M, Gómez Carrera L, Soto Abánades C, Martínez Robles E, Sorriguieta Torre R, Ríos Blanco JJ. Evaluating the diagnostic and prognostic utility of serial KL-6 measurements in connective tissue disease patients at risk for interstitial lung disease: correlations with pulmonary function tests and high-resolution computed tomography. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24:603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shi S, Zou R, Li R, Zhao T, Wu C, Xiao Y, Feng X, Chen L. CD3 + CD4 + T cells counts reflect the severity and prognosis of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Clin Rheumatol. 2025;44:2421-2430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cabrera Cesar E, Lopez-Lopez L, Lara E, Hidalgo-San Juan MV, Parrado Romero C, Palencia JLRS, Martín-Montañez E, Garcia-Fernandez M. Serum Biomarkers in Differential Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis and Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. J Clin Med. 2021;10:3167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi X, Pu X, Cao D, Yan T, Ye Q. Clinical and prognostic features associated with anti-Ro52 autoantibodies in connective tissue diseases patients with interstitial lung disease. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2023;41:2257-2263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Palalane E, Alpizar-Rodriguez D, Botha S, Said-Hartley Q, Calligaro G, Hodkinson B. Interstitial lung disease in patients with connective tissue disease: Subtypes, clinical features and comorbidities in the Western Cape, South Africa. Afr J Thorac Crit Care Med. 2022;28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | He Y, Yu W, Ning P, Luo Q, Zhao L, Xie Y, Yu Y, Ma X, Chen L, Zheng Y, Gao Z. Shared and Specific Lung Microbiota with Metabolic Profiles in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid Between Infectious and Inflammatory Respiratory Diseases. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:187-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang P, Zhang L, Guo Q, Zhao L, Hao Y. Mycophenolate mofetil versus cyclophosphamide plus in patients with connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease: Efficacy and safety analysis. Open Med (Wars). 2023;18:20230838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ding F, Yang L, Wang Y, Wang J, Ma Y, Jin J. Serum Rcn3 level is a potential diagnostic biomarker for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease and reflects the severity of pulmonary function. BMC Pulm Med. 2023;23:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yuan XY, Zhang H, Huang LR, Zhang F, Sheng XW, Cui A. Evaluation of health-related quality of life and the related factors in a group of Chinese patients with interstitial lung diseases. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0236346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chiu YH, Spierings J, de Jong PA, Hoesein FM, Grutters JC, van Laar JM, Voortman M. Predictors for progressive fibrosis in patients with connective tissue disease associated interstitial lung diseases. Respir Med. 2021;187:106579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gagiannis D, Steinestel J, Hackenbroch C, Schreiner B, Hannemann M, Bloch W, Umathum VG, Gebauer N, Rother C, Stahl M, Witte HM, Steinestel K. Clinical, Serological, and Histopathological Similarities Between Severe COVID-19 and Acute Exacerbation of Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease (CTD-ILD). Front Immunol. 2020;11:587517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen L, Zhu M, Lu H, Yang T, Li W, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Li Z, Wan H, Luo F. Quantitative evaluation of disease severity in connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease by dual-energy computed tomography. Respir Res. 2022;23:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/