Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109906

Revised: July 9, 2025

Accepted: October 27, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 186 Days and 18.4 Hours

Autism spectrum disorder is a mental neurodevelopmental condition characterized by social deficits and repetitive behavior, and its development is influ

Core Tip: The pathogenic factors of autism are closely related to maternal health during pregnancy. Adverse factors during pregnancy, such as infections and psychological stress, can affect the development of the offspring’s central and enteric nervous systems, leading to core symptoms of autism and gastrointestinal problems. Therefore, maternal health during pregnancy must be monitored to reduce the incidence of autism.

- Citation: Wang XX. Maternal factors contributing to variability in gut microbiota and gastrointestinal function in autism spectrum disorders. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 109906

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/109906.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.109906

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by core symptoms of impaired social communication, repetitive behaviors, and sensory abnormalities[1]. The estimated global prevalence of ASD is approximately 1%; however, it can be higher in some regions[2]. Concurrently, ASD is frequently accompanied by various comorbidities, such as gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and sleep disturbances[3]. Among these, GI symptoms are the most prevalent comorbidities, affecting up to 4.2%-96.8% of individuals with ASD, and are considered a significant contributor to the overall disease burden[4]. In general, GI symptoms include constipation, abdominal pain, and diarrhea[5]. Emerging evidence suggests a strong link between GI dysfunction and severity of core ASD symptoms; children with more pronounced GI issues often exhibit severe behavioral impairments[6]. Intriguingly, interventions alleviating GI symptoms were found to mitigate core autistic traits, further supporting a potential gut-brain interaction in ASD path

The etiology of ASD involves both genetic predisposition and environmental influences. Among environmental factors, maternal health during pregnancy is crucial in fetal neurodevelopment. Maternal immune activation (MIA), metabolic status, and stress during pregnancy can affect the maternal gut microbiota[8], which is associated with abnormal fetal neurodevelopment and increased ASD risk[9].

Maternal abnormalities during pregnancy can affect the development of the offspring’s nervous system, including the central nervous system (CNS) and enteric nervous system (ENS)[4]. In a previous review[10], maternal exposure was reported as a harmful factor affecting microbiota during pregnancy, which can influence the development of the offspring’s CNS and lead to ASD. In addition, the ENS is mainly involved in the mediation of GI motility and GI sen

Given the increasing prevalence of ASD and the substantial effect of GI comorbidities, further investigation into the interplay among maternal influences, gut dysregulation, and neurobehavioral outcomes is essential for the development of targeted therapeutic strategies. This review aimed to discuss the effects of pregnancy on the GI tract and gut mic

As early as 1982, researchers found that pregnancy can affect the GI motility in women through hormones. High progesterone and estradiol levels can prolong the GI transport time[12]. A recent study showed that pregnancy can remodel the intestinal tract and alter intestinal functions[13]. This evidence indicates that pregnancy is among the factors that alters intestinal function and structure, leading to intestinal dysfunction.

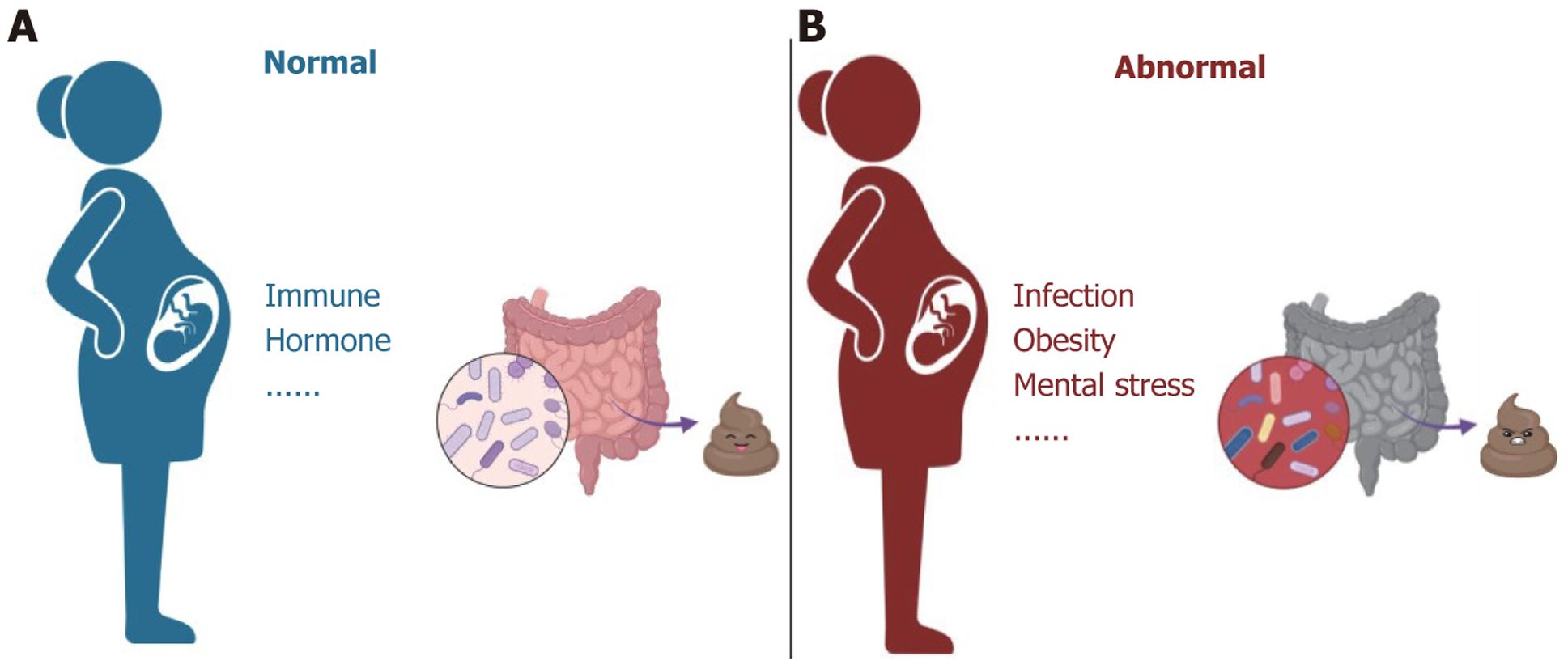

Pregnancy is a very complex physiological process that involves changes in multiple aspects of immunity, hormones, circulation, microbial system, etc. During pregnancy, a woman’s gut microbiota is affected by various factors, such as nutrition, mental state, and toxins[14]. Moreover, pregnancy can affect the function of the GI tract and lead to changes in gut microbiota[15].

During pregnancy, the levels of progesterone and estrogen increase dramatically. Meanwhile, the immune system of pregnant women undergoes considerable changes. Progesterone exhibits an immunosuppressive function, inhibiting T cell activation and natural killer cell toxicity, which promotes a Th2 immune response[16,17]. During pregnancy, regu

Gut microbiome changes during pregnancy have been studied extensively. In normal pregnancies, beta diversity increases markedly from the first trimester (T1) to the third trimester (T3). Conversely, alpha phylogenetic diversity decreases substantially from T1 to T3. In T1, Clostridium genera such as Faecalibacterium and Eubacterium are significantly increased. In T3, members of the Enterobacteriaceae family and Streptococcus genus are enriched[23]. Bifidobacterium, a probiotic, plays a role in maintaining intestinal health and defending against pathogens. In mice, researchers found significantly increased abundance of Bifidobactem in T3, and progesterone also affected the abundance of several bacterial species[24]. This evidence indicates that pregnancy can affect the microbial community through related hormones such as progesterone. In summary, various factors, such as immunity and hormones, influence the intestinal flora during pre

The gut microbiota is sensitive to various environmental factors. Adverse factors such as infections and pregnancy-related stress can cause changes in women’s gut microbiota, leading to abnormalities in their offspring[15,25]. Thus, this review explored changes in the gut microbiota of women who experienced adverse events during pregnancy, such as pregnancy-related diseases, infections, and mental factors.

Due to the physiological changes that occur during pregnancy, many pregnant women may experience different pregnancy-related conditions, such as gestational diabetes and GI symptoms[26]. Buffington et al[27] found that the offsprings of mice that were fed a high-fat diet during pregnancy exhibited impaired social skills and social novelty deficits. Concurrently, oxytocin neurons located in the hypothalamus were damaged, accompanied by changes in the ecology of the gut microbiota. Moreover, supplementation of Lactobacillus reuteri may improve social dysfunction and repair oxytocin neuron function in offspring. Aljumaiah et al[28] found that Clostridium species in type 1 diabetic rats showed overgrowth and could induce autism-like behaviors in the offspring. Treating type 1 diabetic pregnant rats with insulin can reduce inflammation in the brains of their offspring. These findings indicate the importance of fat metabolism for the health of both mother and offspring during pregnancy. It can affect the neurodevelopment of the offspring by influencing the extent of inflammation.

GI symptoms are common and reduce the quality of life during pregnancy. Owing to the influence of hormones, particularly progesterone, pregnant women often experience symptoms of reduced GI motility, such as constipation[29]. Despite the lack of clinical studies on constipation-related changes in the gut flora in pregnant women, a clinical trial revealed that administering a combination of probiotics to pregnant women can relieve constipation symptoms, such as anorectal sensation and incomplete evacuation[30]. The effect of constipation during pregnancy on the intestinal flora of pregnant women and their offspring’s mental development must be further examined. However, probiotics may be promising agents to treat GI disorders during pregnancy. These findings imply that physiological changes during pre

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic disease related to immune system disorders, changes in the intestinal microbiota, and malabsorption of micronutrients. Evidence suggests an association between the genetic susceptibility of mothers to IBD and the characteristics of autism in children[31]. Perinatal IBD may be related to ASD occurrence[32-35]. In a clinical research, women with IBD during pregnancy had reduced gut microbiota diversity and altered bacterial composition. Moreover, the mothers with IBD during pregnancy and their offspring showed decreased levels of Gammaproteobacteria and Bacteroidetes. This phenomenon may be related to the conversion of memory B cells and re

MIA during pregnancy is an important pathogenic factor of ASD. In multiple animal models of MIA, the offspring of animals with perinatal MIA showed high levels of inflammatory factors, social deficits, and stereotyped behaviors[37-39]. Meanwhile, IL-6 and IL-17a are considered to be significantly related to ASD development, and they are significantly increased in the MIA model[40,41].

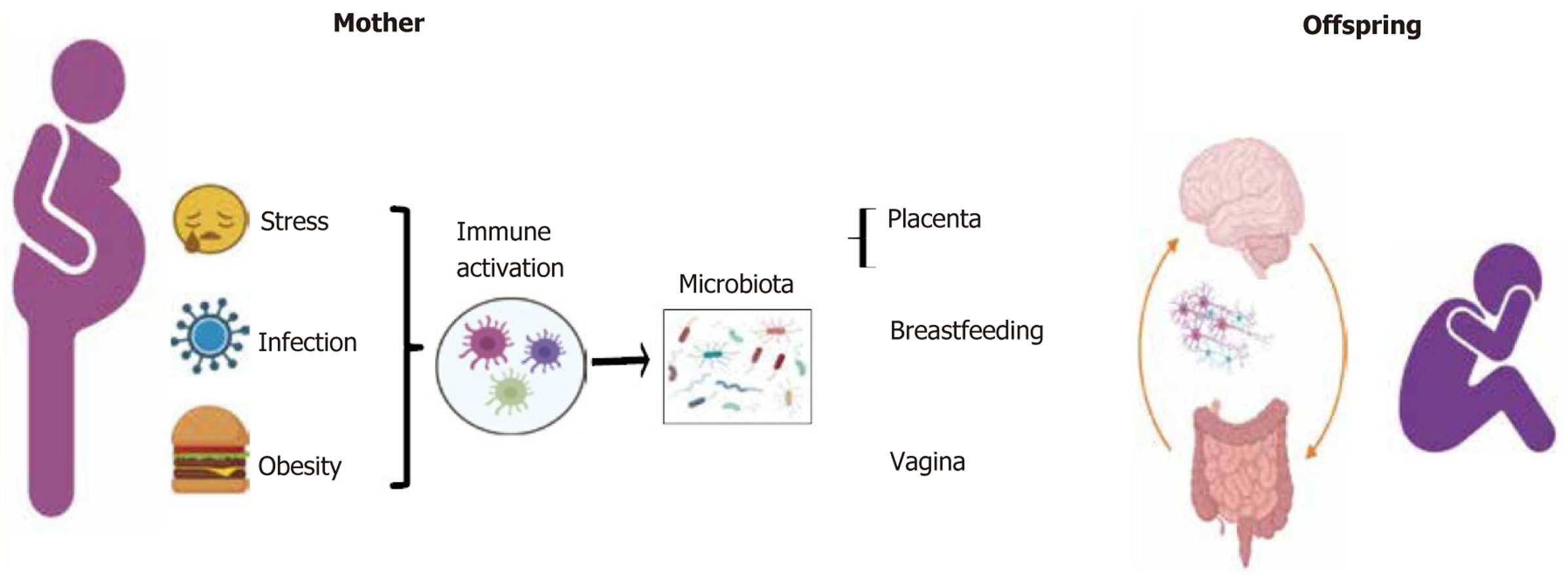

Pregnancy is a long-term process of physiological and psychological changes. During this process, mothers are exposed to various stressors, including social, personal, and psychological factors and disasters[42,43]. The relative abundance of Proteus and Escherichia coli increased in the intestines of mice exposed to maternal prenatal tress, whereas the relative abundance of Lactobacillus decreased[44]. Clinical studies have suggested that during pregnancy, women with high anxiety levels exhibit relatively higher abundance levels of oxalate, acetic acid bacteria, Acidinococcus, and Staphylococcus[45,46]. Maternal prenatal stress induces changes in the composition of the maternal GI and vaginal microbiota, which are vertically transmitted to the offspring, leading to an imbalance in the offspring’s gut microbiota[44,47,48]. Furthermore, stress during pregnancy can lead to the excessive release of cortisol, which can pass through the placenta and breast milk to the fetus, affecting the composition of the fetal gut microbiota[45,49,50]. Maternal prenatal stress can lead to changes in the diversity and abundance of the offspring’s gut microbiota, cause immune and GI dysfunction, and reduce neural innervation of the colon (Figure 1). These effects may increase the risk of digestive symptoms in the offspring[51,52]. Therefore, maternal stress during pregnancy may alter the composition of the maternal gut microbiota and affect the neurodevelopment and behavioral performance of the offspring.

Many factors can cause disturbances in the gut microbiota during pregnancy, such as obesity and infection. Abnormal maternal microbiome during pregnancy contributes to ASD development[53]. A clinical meta-analysis found that the offspring of women who were obese during pregnancy had a higher risk of developing ASD than those born to women with a normal weight[54]. Importantly, the gut microbiota is formed in the first few years of life. It regulates important processes such as digestion and immune response. A widespread consensus is that patients with ASD have abnormal intestinal microbiota[4,55]. The etiology of and abnormal gut microbiota in ASD are closely linked to changes in the maternal microbiota[55,56]. Meanwhile, the GI problem is one of the complications of ASD, which commonly occur in individuals with ASD. Moreover, the correlation between GI dysfunction and behavioral symptom severity is evident. The GI system is not only regulated by the CNS but also by the ENS. Therefore, the effect of abnormalities in the maternal intestinal microbiota on individuals with ASD is discussed from the perspectives of both CNS and ENS.

In a review by Sarkar et al[57], the gut microbiota was reported to be crucial to the development of social brain. The gut microbiota can affect the expression of oxytocin in the hypothalamus as well as the development of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis[57]. Moreover, the excitability of oxytocin neurons projected from the paraventricular nuclei to the ventral tegmental area has been reported to decrease. Furthermore, the administration of Lactobacillus reuteri to the offspring can repair the function of oxytocin neurons and improve ASD-like symptoms[27]. Maternal stress can lead to an increase in cortisol levels in the brain of the offspring and a decrease in the abundance of Parasutterella excrementihominis in the gut[8]. Besides, the placenta secretes corticotropin-releasing factor to regulate the fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, which is an important factor for the fetal adrenal gland to produce glucocorticoids and androgens[58,59]. When the mother is under stress, fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis deve

Mothers following a high-fat diet may experience metabolic problems that affect metabolic derivatives, potentially resulting in abnormal neural development in their offspring through the bloodstream[63]. The above results suggest that the risk factors that the mother is exposed to during pregnancy can cause abnormalities in the offspring’s CNS and affect the composition of the offspring’s intestinal microbiota, disrupting the brain-gut axis in the offspring and resulting in ASD-like changes in the behavior of the offspring.

ASD is a CNS-mediated neurobehavioral disorder; thus, most studies on ASD have focused on the CNS. However, GI function is not only affected by the abnormal function of the neural mechanistic nature of ASD but also by ENS. Therefore, it is not surprising that GI diseases, particularly diarrhea and abdominal pain, have high comorbidity rates in patients with ASD[4]. As for the CNS, substantial data about ENS deficiency in ASD have been obtained using germ-free mice. In these mice, abnormalities in ENS development included a reduction in the total number of neurons in the intestine and changes in subtype distribution, which were associated with abnormal gut motility[64-67]. Coincidentally, in the valproic acid-induced (VPA) rat model, rats exposed to VPA during pregnancy exhibited abnormal gut microbiota and intestinal pathological alteration. The offspring of VPA rats also showed intestinal dysfunction, including impaired intestinal motility, high levels of intestinal inflammation, and changes in the microbiota composition[68,69]. For instance, some ASD-related genes, such as shank3, are also expressed in the ENS. Thus, reduced intestinal motility can be observed in shank3-mutant mice and zebrafish. The expression of serotonin, which is associated with intestinal motility, decreased in the ENS, whereas the expression of inflammatory factors and permeability increased in the ENS[62,70]. Therefore, both the CNS and ENS are deemed crucial in the pathogenesis of ASD. Abnormalities in either the CNS or ENS can lead to the occurrence of ASD-related GI problems.

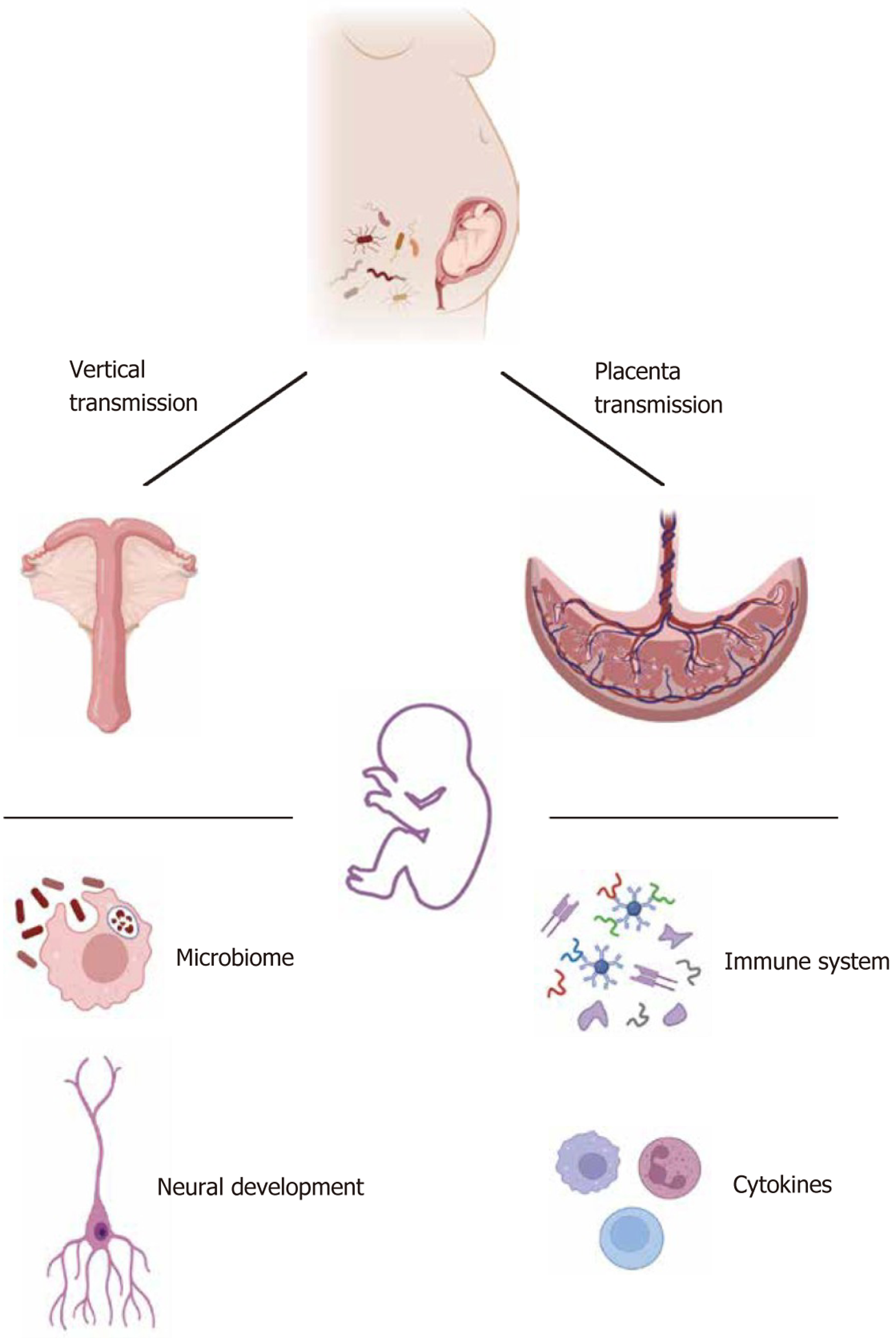

In humans and other mammals, the intestinal microbiota in early life is seeded by microorganisms found in the environment. Gut microbiota colonization can be influenced by maternal symbiotic bacteria, which are present in several parts of the maternal body such as the birth canal, skin, and gut[71,72]. The maternal intestinal microbiota can disrupt the balance of the offspring’s intestinal microbiota by influencing the colonization, hormone levels, and gene expression of the offspring and then mediating the development of the offspring’s nervous system, leading to ASD occurrence.

An offspring inherits commensal microbiota from their mother[72]. Immediately after birth, the same intestinal and vaginal microbiota as the mother can be found in the infant’s feces[73]. Moreover, the gut microbiota of vaginally delivered infants is similar to that of their mothers, with Lactobacillus and Prevotella being the main organisms. In addition, the types of bacteria acquired by infants born through cesarean section are similar to those on the skin surface of their mothers, with Staphylococcus, Corynebacterium, and Propionibacterium being the main organisms[73]. Ferretti et al[74] re

During normal pregnancy, inflammatory and immune changes required for pregnancy affect maternal intestinal function and microbiota composition, which are caused by hormonal changes, in particular the pregnancy-specific hormone secreted by the placenta, i.e., human chronic gonadotropin. Human chronic gonadotropin regulates estrogen and progesterone secretion, thereby influencing the composition of the maternal gut microbiota. High progesterone levels increase the GI transit time, which is a key factor in shaping the composition of the intestinal microbiota[78,79]. More importantly, the placenta influences fetal development and is an important barrier between the mother and the fetus for hormone production and nutrient secretion and absorption. In a healthy pregnancy, the placenta also has a microbiota that helps in the development of the immune system of the fetus. Metabolites of the maternal intestinal microbiota, such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), can enter the bloodstream through the liver, pass through the placental barrier, and promote the formation of the fetal blood–brain barrier and innate immunity. SCFAs can cross the blood-brain barrier, influencing CNS activity, including microglia and cytokine modulation[80]. Women who follow a vegetarian diet during pregnancy can produce SCFAs with immune-protective effects, which is associated with the high relative abundance of Roseburia and Lachnospiraceae[81]. In the maternal stress model, the abnormal composition of the maternal intestinal microbiota caused abnormalities in the transfer of placental nutrients, resulting in the abnormal development of the hypothalamus and limbic system in male offspring[82]. These findings indicate that the maternal gut microbiota during pregnancy can affect the development of the nervous system of the offspring, and the mechanism is influenced by the immune system and hormones produced by the placenta. The transmission of maternal intestinal microbiota to offspring is illustrated in Figure 2.

Perinatal immune activation, including infections and psychological stress, can lead to abnormalities in the gut flora and severe inflammation in the mother. Pregnancy-related stress can affect the microbial composition and gut function of the offspring[72,83-85]. In the stress mouse model, the high levels of IL-6 and IL-1β in the placenta downregulate the level of dopamine receptors in the nucleus accumbens of male offspring, resulting in motor dysfunction[86]. Garcia-Flores et al[87] demonstrated a systemic reduction in B and T cells in the F1 and F2 offsprings of mice after prenatal stress. In women with anxiety and depression during pregnancy, the methylation coding of 11β-HSD2 and Nr3c1 in the placenta increased, which was positively correlated with neurobehavioral defects in infants[88,89]. Another study indicated that stress during pregnancy cannot only cause methylation of the placental 11β-HSD2 promoter but can also increase in DNA methyltransferase 3A[90].

Lombardo et al[91] evaluated the transcriptome in the cerebral cortex of MIA rat offspring. The offspring showed downregulation of many gene enrichment pathways associated with permeability, and these genes were associated with ASD development. In human fetal brain tissue and human neural stem cells, although MIA did not cause abnormal expression levels in FMRP and CHD8, the expression of downstream targets was disrupted. These downregulated genes are involved in axonal routing, synaptogenesis, and network formation[91]. Overall, at the molecular level, prenatal stress alters placental function and signaling by altering epigenetic mechanisms.

During pregnancy, after exposure to adverse factors (such as stress and infections), the maternal intestinal flora becomes disordered, which eventually affects the development of the offspring’s nervous and immune systems. Abnormal neurodevelopment in the offspring affects not only the CNS but also the ENS. In some animal models of ASD with microbiota problems, the regions of the brain that regulate cognition and emotion were disturbed[92]. Some neurotransmitters that regulate GI function are impaired[68,93]. In the MIA model, IL-17a levels in the cerebral cortex increased[41]. IL-17a is secreted by Th17 cells. Under normal pregnancy conditions, Th17 cells can inhibit mucosal inflammation and exert a protective effect on the mucosal barrier[25,94]. The GI symptoms of ASD have also been confirmed to be related to barrier disruption[95]. Therefore, inferring that the GI symptoms of ASD are the result of the interaction between the nervous system and the immune system (Figure 3) is not difficult. It is precisely for this reason that GI symptoms have become one of the most common ASD complications.

Maternal health is crucial for the normal development of the offspring. Therefore, paying attention to maternal health during pregnancy and adjusting the intestinal flora during this period are important measures to reduce ASD prevalence. First, women should take care of their health during pregnancy to avoid infections, maintain a positive mood, and reduce negative emotions caused by stress and anxiety. Pregnant women with underlying medical conditions should increase their communication with doctors. This will help control the effect of pregnancy on the primary disease. In clinical research, certain studies have attempted to use probiotics for intervention during pregnancy. For example, Lactobacillus species play an important role in supporting intestinal health and regulating immunity. Bifidobacterium species maintain intestinal barrier function and aid in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Saccharomyces species can reduce diarrheal symptoms caused by antibiotics and support the immune function[96]. However, the results of studies ana

In addition, the feasibility of using probiotics for intervention during pregnancy needs to consider ethical issues. Bacteria used as probiotics must undergo a thorough safety assessment. Probiotics to be used as drugs must be approved by the Food and Drug Administration[99]. Previous studies have not clearly concluded on the optimal duration of pro

Improving the intestinal flora is a common treatment approach in patients with ASD. Many studies have performed microbiota transplantation and oral supplementation of probiotics to treat ASD[102,103]. Microbiota regulation can improve the core symptoms of ASD model mice, and mechanisms may be related to the intestinal microbiota and vagus nerve[104,105]. The vagus nerve, which is composed of 80% afferent fibers and 20% efferent fibers, is crucial for internal sensing. It can detect metabolites produced by the microbiota through its afferents and transmit intestinal information to the CNS for processing[106]. In addition, the vagus nerve is influenced by the intestinal microbiota and helps regulate the cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway, thereby reducing inflammation and lowering intestinal permeability[107]. Therefore, certain methods are available for treating autism through neuroregulation that positively affect the social interaction of ASD[68,108]. Our unpublished data indicate that transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation can sig

At present, no direct evidence supports the analysis of the interaction between the quality of a person’s diet and changes in the gut microbiota during pregnancy. Moreover, currently, the effects of maternal microbiota on offspring are pri

In addition to the core symptoms of social deficits, stereotyped behaviors, and abnormal sensations, GI problems are common comorbidities in patients with ASD. The main symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, and constipation, which seriously affect the quality of life of people with ASD. The abnormality of the maternal intestinal flora is a sig

| 1. | Lord C, Brugha TS, Charman T, Cusack J, Dumas G, Frazier T, Jones EJH, Jones RM, Pickles A, State MW, Taylor JL, Veenstra-VanderWeele J. Autism spectrum disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 155.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maenner MJ, Warren Z, Williams AR, Amoakohene E, Bakian AV, Bilder DA, Durkin MS, Fitzgerald RT, Furnier SM, Hughes MM, Ladd-Acosta CM, McArthur D, Pas ET, Salinas A, Vehorn A, Williams S, Esler A, Grzybowski A, Hall-Lande J, Nguyen RHN, Pierce K, Zahorodny W, Hudson A, Hallas L, Mancilla KC, Patrick M, Shenouda J, Sidwell K, DiRienzo M, Gutierrez J, Spivey MH, Lopez M, Pettygrove S, Schwenk YD, Washington A, Shaw KA. Prevalence and Characteristics of Autism Spectrum Disorder Among Children Aged 8 Years - Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network, 11 Sites, United States, 2020. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2023;72:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 1285] [Article Influence: 428.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang XL, Liang S, Zou MY, Sun CH, Han PP, Jiang XT, Xia W, Wu LJ. Are gastrointestinal and sleep problems associated with behavioral symptoms of autism spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Res. 2018;259:229-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hung LY, Margolis KG. Autism spectrum disorders and the gastrointestinal tract: insights into mechanisms and clinical relevance. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;21:142-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Deng W, Wang S, Li F, Wang F, Xing YP, Li Y, Lv Y, Ke H, Li Z, Lv PJ, Hao H, Chen Y, Xiao X. Gastrointestinal symptoms have a minor impact on autism spectrum disorder and associations with gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acids. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1000419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li H, Huang S, Jing J, Yu H, Gu T, Ou X, Pan S, Zhu Y, Su X. Dietary intake and gastrointestinal symptoms are altered in children with Autism Spectrum Disorder: the relative contribution of autism-linked traits. Nutr J. 2024;23:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tomaszek N, Urbaniak AD, Bałdyga D, Chwesiuk K, Modzelewski S, Waszkiewicz N. Unraveling the Connections: Eating Issues, Microbiome, and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients. 2025;17:486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Antonson AM, Evans MV, Galley JD, Chen HJ, Rajasekera TA, Lammers SM, Hale VL, Bailey MT, Gur TL. Unique maternal immune and functional microbial profiles during prenatal stress. Sci Rep. 2020;10:20288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tartaglione AM, Villani A, Ajmone-Cat MA, Minghetti L, Ricceri L, Pazienza V, De Simone R, Calamandrei G. Maternal immune activation induces autism-like changes in behavior, neuroinflammatory profile and gut microbiota in mouse offspring of both sexes. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Di Gesù CM, Buffington SA. The early life exposome and autism risk: a role for the maternal microbiome? Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2385117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang X, Tang R, Wei Z, Zhan Y, Lu J, Li Z. The enteric nervous system deficits in autism spectrum disorder. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1101071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wald A, Van Thiel DH, Hoechstetter L, Gavaler JS, Egler KM, Verm R, Scott L, Lester R. Effect of pregnancy on gastrointestinal transit. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:1015-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ameku T, Laddach A, Beckwith H, Milona A, Rogers LS, Schwayer C, Nye E, Tough IR, Thoumas JL, Gautam UK, Wang YF, Jha S, Castano-Medina A, Amourda C, Vaelli PM, Gevers S, Irvine EE, Meyer L, Andrew I, Choi KL, Patel B, Francis AJ, Studd C, Game L, Young G, Murphy KG, Owen B, Withers DJ, Rodriguez-Colman M, Cox HM, Liberali P, Schwarzer M, Leulier F, Pachnis V, Bellono NW, Miguel-Aliaga I. Growth of the maternal intestine during reproduction. Cell. 2025;188:2738-2756.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mate A, Reyes-Goya C, Santana-Garrido Á, Vázquez CM. Lifestyle, Maternal Nutrition and Healthy Pregnancy. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2021;19:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu ZZ, Sun JH, Wang WJ. Gut microbiota in gastrointestinal diseases during pregnancy. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:2976-2989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Zwahlen M, Stute P. Impact of progesterone on the immune system in women: a systematic literature review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309:37-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rao VA, Kurian NK, Rao KA. Cytokines, NK cells and regulatory T cell functions in normal pregnancy and reproductive failures. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2023;89:e13667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang H, Wang LL, Zhao SJ, Lin XX, Liao AH. IL-10: A bridge between immune cells and metabolism during pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2022;154:103750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mu Q, Cabana-Puig X, Mao J, Swartwout B, Abdelhamid L, Cecere TE, Wang H, Reilly CM, Luo XM. Pregnancy and lactation interfere with the response of autoimmunity to modulation of gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2019;7:105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Muzzio D, Zygmunt M, Jensen F. The role of pregnancy-associated hormones in the development and function of regulatory B cells. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2014;5:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Monteiro C, Kasahara T, Sacramento PM, Dias A, Leite S, Silva VG, Gupta S, Agrawal A, Bento CAM. Human pregnancy levels of estrogen and progesterone contribute to humoral immunity by activating T(FH) /B cell axis. Eur J Immunol. 2021;51:167-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Collins MK, McCutcheon CR, Petroff MG. Impact of Estrogen and Progesterone on Immune Cells and Host-Pathogen Interactions in the Lower Female Reproductive Tract. J Immunol. 2022;209:1437-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, Gonzalez A, Werner JJ, Angenent LT, Knight R, Bäckhed F, Isolauri E, Salminen S, Ley RE. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150:470-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1438] [Cited by in RCA: 1534] [Article Influence: 109.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nuriel-Ohayon M, Neuman H, Ziv O, Belogolovski A, Barsheshet Y, Bloch N, Uzan A, Lahav R, Peretz A, Frishman S, Hod M, Hadar E, Louzoun Y, Avni O, Koren O. Progesterone Increases Bifidobacterium Relative Abundance during Late Pregnancy. Cell Rep. 2019;27:730-736.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Estes ML, McAllister AK. Brain, Immunity, Gut: "BIG" Links between Pregnancy and Autism. Immunity. 2017;47:816-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jain A, Ramchandani S, Bhatia S. Gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders of gut-brain interaction in pregnancy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Buffington SA, Di Prisco GV, Auchtung TA, Ajami NJ, Petrosino JF, Costa-Mattioli M. Microbial Reconstitution Reverses Maternal Diet-Induced Social and Synaptic Deficits in Offspring. Cell. 2016;165:1762-1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 100.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Aljumaiah MM, Alonazi MA, Al-Dbass AM, Almnaizel AT, Alahmed M, Soliman DA, El-Ansary A. Association of Maternal Diabetes and Autism Spectrum Disorders in Offspring: a Study in a Rodent Model of Autism. J Mol Neurosci. 2022;72:349-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kazma JM, van den Anker J, Allegaert K, Dallmann A, Ahmadzia HK. Anatomical and physiological alterations of pregnancy. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2020;47:271-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Milliano I, Tabbers MM, van der Post JA, Benninga MA. Is a multispecies probiotic mixture effective in constipation during pregnancy? 'A pilot study'. Nutr J. 2012;11:80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sadik A, Dardani C, Pagoni P, Havdahl A, Stergiakouli E; iPSYCH Autism Spectrum Disorder Working Group, Khandaker GM, Sullivan SA, Zammit S, Jones HJ, Davey Smith G, Dalman C, Karlsson H, Gardner RM, Rai D. Parental inflammatory bowel disease and autism in children. Nat Med. 2022;28:1406-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Osokine I, Erlebacher A. Inflammation and Autism: From Maternal Gut to Fetal Brain. Trends Mol Med. 2017;23:1070-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | DeVilbiss EA, Magnusson C, Gardner RM, Rai D, Newschaffer CJ, Lyall K, Dalman C, Lee BK. Antenatal nutritional supplementation and autism spectrum disorders in the Stockholm youth cohort: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2017;359:j4273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tan M, Yang T, Zhu J, Li Q, Lai X, Li Y, Tang T, Chen J, Li T. Maternal folic acid and micronutrient supplementation is associated with vitamin levels and symptoms in children with autism spectrum disorders. Reprod Toxicol. 2020;91:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wiegersma AM, Dalman C, Lee BK, Karlsson H, Gardner RM. Association of Prenatal Maternal Anemia With Neurodevelopmental Disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1294-1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Torres J, Hu J, Seki A, Eisele C, Nair N, Huang R, Tarassishin L, Jharap B, Cote-Daigneault J, Mao Q, Mogno I, Britton GJ, Uzzan M, Chen CL, Kornbluth A, George J, Legnani P, Maser E, Loudon H, Stone J, Dubinsky M, Faith JJ, Clemente JC, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peter I. Infants born to mothers with IBD present with altered gut microbiome that transfers abnormalities of the adaptive immune system to germ-free mice. Gut. 2020;69:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Machado CJ, Whitaker AM, Smith SE, Patterson PH, Bauman MD. Maternal immune activation in nonhuman primates alters social attention in juvenile offspring. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;77:823-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Malkova NV, Yu CZ, Hsiao EY, Moore MJ, Patterson PH. Maternal immune activation yields offspring displaying mouse versions of the three core symptoms of autism. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:607-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, Sharon G, Hyde ER, McCue T, Codelli JA, Chow J, Reisman SE, Petrosino JF, Patterson PH, Mazmanian SK. Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. 2013;155:1451-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2084] [Cited by in RCA: 2439] [Article Influence: 187.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Wei H, Chadman KK, McCloskey DP, Sheikh AM, Malik M, Brown WT, Li X. Brain IL-6 elevation causes neuronal circuitry imbalances and mediates autism-like behaviors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1822:831-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Choi GB, Yim YS, Wong H, Kim S, Kim H, Kim SV, Hoeffer CA, Littman DR, Huh JR. The maternal interleukin-17a pathway in mice promotes autism-like phenotypes in offspring. Science. 2016;351:933-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 778] [Cited by in RCA: 928] [Article Influence: 92.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Van den Bergh BRH, van den Heuvel MI, Lahti M, Braeken M, de Rooij SR, Entringer S, Hoyer D, Roseboom T, Räikkönen K, King S, Schwab M. Prenatal developmental origins of behavior and mental health: The influence of maternal stress in pregnancy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;117:26-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 759] [Article Influence: 126.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Naudé PJW, Claassen-Weitz S, Gardner-Lubbe S, Botha G, Kaba M, Zar HJ, Nicol MP, Stein DJ. Association of maternal prenatal psychological stressors and distress with maternal and early infant faecal bacterial profile. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2020;32:32-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yeramilli V, Cheddadi R, Shah J, Brawner K, Martin C. A Review of the Impact of Maternal Prenatal Stress on Offspring Microbiota and Metabolites. Metabolites. 2023;13:535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hechler C, Borewicz K, Beijers R, Saccenti E, Riksen-Walraven M, Smidt H, de Weerth C. Association between Psychosocial Stress and Fecal Microbiota in Pregnant Women. Sci Rep. 2019;9:4463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mepham J, Nelles-McGee T, Andrews K, Gonzalez A. Exploring the effect of prenatal maternal stress on the microbiomes of mothers and infants: A systematic review. Dev Psychobiol. 2023;65:e22424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wang S, Ryan CA, Boyaval P, Dempsey EM, Ross RP, Stanton C. Maternal Vertical Transmission Affecting Early-life Microbiota Development. Trends Microbiol. 2020;28:28-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Agusti A, Lamers F, Tamayo M, Benito-Amat C, Molina-Mendoza GV, Penninx BWJH, Sanz Y. The Gut Microbiome in Early Life Stress: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2023;15:2566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Irwin JL, Meyering AL, Peterson G, Glynn LM, Sandman CA, Hicks LM, Davis EP. Maternal prenatal cortisol programs the infant hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2021;125:105106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zijlmans MA, Riksen-Walraven JM, de Weerth C. Associations between maternal prenatal cortisol concentrations and child outcomes: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;53:1-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Golubeva AV, Crampton S, Desbonnet L, Edge D, O'Sullivan O, Lomasney KW, Zhdanov AV, Crispie F, Moloney RD, Borre YE, Cotter PD, Hyland NP, O'Halloran KD, Dinan TG, O'Keeffe GW, Cryan JF. Prenatal stress-induced alterations in major physiological systems correlate with gut microbiota composition in adulthood. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;60:58-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Rusconi F, Gagliardi L, Gori E, Porta D, Popovic M, Asta F, Brescianini S, Richiardi L, Ronfani L, Stazi MA. Perinatal maternal mental health is associated with both infections and wheezing in early childhood. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2019;30:732-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Love C, Sominsky L, O'Hely M, Berk M, Vuillermin P, Dawson SL. Prenatal environmental risk factors for autism spectrum disorder and their potential mechanisms. BMC Med. 2024;22:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Li YM, Ou JJ, Liu L, Zhang D, Zhao JP, Tang SY. Association Between Maternal Obesity and Autism Spectrum Disorder in Offspring: A Meta-analysis. J Autism Dev Disord. 2016;46:95-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Suprunowicz M, Tomaszek N, Urbaniak A, Zackiewicz K, Modzelewski S, Waszkiewicz N. Between Dysbiosis, Maternal Immune Activation and Autism: Is There a Common Pathway? Nutrients. 2024;16:549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Minakova E, Warner BB. Maternal immune activation, central nervous system development and behavioral phenotypes. Birth Defects Res. 2018;110:1539-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Sarkar A, Harty S, Johnson KV, Moeller AH, Carmody RN, Lehto SM, Erdman SE, Dunbar RIM, Burnet PWJ. The role of the microbiome in the neurobiology of social behaviour. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2020;95:1131-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Smith R, Mesiano S, Chan EC, Brown S, Jaffe RB. Corticotropin-releasing hormone directly and preferentially stimulates dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate secretion by human fetal adrenal cortical cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:2916-2920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Wadhwa PD, Sandman CA, Chicz-DeMet A, Porto M. Placental CRH modulates maternal pituitary adrenal function in human pregnancy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;814:276-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Mastorakos G, Ilias I. Maternal and fetal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axes during pregnancy and postpartum. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;997:136-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 368] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tabouy L, Getselter D, Ziv O, Karpuj M, Tabouy T, Lukic I, Maayouf R, Werbner N, Ben-Amram H, Nuriel-Ohayon M, Koren O, Elliott E. Dysbiosis of microbiome and probiotic treatment in a genetic model of autism spectrum disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;73:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Sauer AK, Bockmann J, Steinestel K, Boeckers TM, Grabrucker AM. Altered Intestinal Morphology and Microbiota Composition in the Autism Spectrum Disorders Associated SHANK3 Mouse Model. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Di Gesù CM, Matz LM, Bolding IJ, Fultz R, Hoffman KL, Gammazza AM, Petrosino JF, Buffington SA. Maternal gut microbiota mediate intergenerational effects of high-fat diet on descendant social behavior. Cell Rep. 2022;41:111461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Chen Y, Fang H, Li C, Wu G, Xu T, Yang X, Zhao L, Ke X, Zhang C. Gut Bacteria Shared by Children and Their Mothers Associate with Developmental Level and Social Deficits in Autism Spectrum Disorder. mSphere. 2020;5:e01044-e01020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Anitha M, Vijay-Kumar M, Sitaraman SV, Gewirtz AT, Srinivasan S. Gut microbial products regulate murine gastrointestinal motility via Toll-like receptor 4 signaling. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1006-16.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Kashyap PC, Marcobal A, Ursell LK, Larauche M, Duboc H, Earle KA, Sonnenburg ED, Ferreyra JA, Higginbottom SK, Million M, Tache Y, Pasricha PJ, Knight R, Farrugia G, Sonnenburg JL. Complex interactions among diet, gastrointestinal transit, and gut microbiota in humanized mice. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:967-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 27.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Hyland NP, Cryan JF. Microbe-host interactions: Influence of the gut microbiota on the enteric nervous system. Dev Biol. 2016;417:182-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Li S, Zhang N, Li W, Zhang HL, Wang XX. Gastrointestinal problems in a valproic acid-induced rat model of autism: From maternal intestinal health to offspring intestinal function. World J Psychiatry. 2024;14:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 69. | Gu Y, Han Y, Ren S, Zhang B, Zhao Y, Wang X, Zhang S, Qin J. Correlation among gut microbiota, fecal metabolites and autism-like behavior in an adolescent valproic acid-induced rat autism model. Behav Brain Res. 2022;417:113580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | James DM, Kozol RA, Kajiwara Y, Wahl AL, Storrs EC, Buxbaum JD, Klein M, Moshiree B, Dallman JE. Intestinal dysmotility in a zebrafish (Danio rerio) shank3a;shank3b mutant model of autism. Mol Autism. 2019;10:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | McDonald B, McCoy KD. Maternal microbiota in pregnancy and early life. Science. 2019;365:984-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Tochitani S. Vertical transmission of gut microbiota: Points of action of environmental factors influencing brain development. Neurosci Res. 2021;168:83-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Dominguez-Bello MG, Costello EK, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Fierer N, Knight R. Delivery mode shapes the acquisition and structure of the initial microbiota across multiple body habitats in newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11971-11975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2922] [Cited by in RCA: 3298] [Article Influence: 206.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 74. | Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, Asnicar F, Gorfer V, Fedi S, Armanini F, Truong DT, Manara S, Zolfo M, Beghini F, Bertorelli R, De Sanctis V, Bariletti I, Canto R, Clementi R, Cologna M, Crifò T, Cusumano G, Gottardi S, Innamorati C, Masè C, Postai D, Savoi D, Duranti S, Lugli GA, Mancabelli L, Turroni F, Ferrario C, Milani C, Mangifesta M, Anzalone R, Viappiani A, Yassour M, Vlamakis H, Xavier R, Collado CM, Koren O, Tateo S, Soffiati M, Pedrotti A, Ventura M, Huttenhower C, Bork P, Segata N. Mother-to-Infant Microbial Transmission from Different Body Sites Shapes the Developing Infant Gut Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;24:133-145.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 698] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 113.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Chu DM, Ma J, Prince AL, Antony KM, Seferovic MD, Aagaard KM. Maturation of the infant microbiome community structure and function across multiple body sites and in relation to mode of delivery. Nat Med. 2017;23:314-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 550] [Cited by in RCA: 753] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Hill CJ, Lynch DB, Murphy K, Ulaszewska M, Jeffery IB, O'Shea CA, Watkins C, Dempsey E, Mattivi F, Tuohy K, Ross RP, Ryan CA, O'Toole PW, Stanton C. Erratum to: Evolution of gut microbiota composition from birth to 24 weeks in the INFANTMET Cohort. Microbiome. 2017;5:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Johnson MH. Functional brain development in humans. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:475-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 595] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Procházková N, Falony G, Dragsted LO, Licht TR, Raes J, Roager HM. Advancing human gut microbiota research by considering gut transit time. Gut. 2023;72:180-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 60.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sajdel-Sulkowska EM. The Impact of Maternal Gut Microbiota during Pregnancy on Fetal Gut-Brain Axis Development and Life-Long Health Outcomes. Microorganisms. 2023;11:2199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Ju S, Shin Y, Han S, Kwon J, Choi TG, Kang I, Kim SS. The Gut-Brain Axis in Schizophrenia: The Implications of the Gut Microbiome and SCFA Production. Nutrients. 2023;15:4391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Barrett HL, Gomez-Arango LF, Wilkinson SA, McIntyre HD, Callaway LK, Morrison M, Dekker Nitert M. A Vegetarian Diet Is a Major Determinant of Gut Microbiota Composition in Early Pregnancy. Nutrients. 2018;10:890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Jašarević E, Howard CD, Misic AM, Beiting DP, Bale TL. Stress during pregnancy alters temporal and spatial dynamics of the maternal and offspring microbiome in a sex-specific manner. Sci Rep. 2017;7:44182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Brawner KM, Yeramilli VA, Kennedy BA, Patel RK, Martin CA. Prenatal stress increases IgA coating of offspring microbiota and exacerbates necrotizing enterocolitis-like injury in a sex-dependent manner. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:291-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Jašarević E, Howard CD, Morrison K, Misic A, Weinkopff T, Scott P, Hunter C, Beiting D, Bale TL. The maternal vaginal microbiome partially mediates the effects of prenatal stress on offspring gut and hypothalamus. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1061-1071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Yeramilli VA, Brawner KM, Crossman DK, Barnum SR, Martin CA. RNASeq analysis reveals upregulation of complement C3 in the offspring gut following prenatal stress in mice. Immunobiology. 2020;225:151983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Bronson SL, Bale TL. Prenatal stress-induced increases in placental inflammation and offspring hyperactivity are male-specific and ameliorated by maternal antiinflammatory treatment. Endocrinology. 2014;155:2635-2646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Garcia-Flores V, Romero R, Furcron AE, Levenson D, Galaz J, Zou C, Hassan SS, Hsu CD, Olson D, Metz GAS, Gomez-Lopez N. Prenatal Maternal Stress Causes Preterm Birth and Affects Neonatal Adaptive Immunity in Mice. Front Immunol. 2020;11:254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Conradt E, Lester BM, Appleton AA, Armstrong DA, Marsit CJ. The roles of DNA methylation of NR3C1 and 11β-HSD2 and exposure to maternal mood disorder in utero on newborn neurobehavior. Epigenetics. 2013;8:1321-1329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Appleton AA, Lester BM, Armstrong DA, Lesseur C, Marsit CJ. Examining the joint contribution of placental NR3C1 and HSD11B2 methylation for infant neurobehavior. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;52:32-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Jensen Peña C, Monk C, Champagne FA. Epigenetic effects of prenatal stress on 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase-2 in the placenta and fetal brain. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Lombardo MV, Moon HM, Su J, Palmer TD, Courchesne E, Pramparo T. Maternal immune activation dysregulation of the fetal brain transcriptome and relevance to the pathophysiology of autism spectrum disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2018;23:1001-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Ogbonnaya ES, Clarke G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF, O'Leary OF. Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis Is Regulated by the Microbiome. Biol Psychiatry. 2015;78:e7-e9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:666-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1385] [Article Influence: 106.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 94. | Lombardelli L, Logiodice F, Aguerre-Girr M, Kullolli O, Haller H, Casart Y, Berrebi A, L'Faqihi-Olive FE, Duplan V, Romagnani S, Maggi E, Rukavina D, Le Bouteiller P, Piccinni MP. Interleukin-17-producing decidual CD4+ T cells are not deleterious for human pregnancy when they also produce interleukin-4. Clin Mol Allergy. 2016;14:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Dargenio VN, Dargenio C, Castellaneta S, De Giacomo A, Laguardia M, Schettini F, Francavilla R, Cristofori F. Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis: Possible Implications in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients. 2023;15:1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Perna A, Venditti N, Merolla F, Fusco S, Guerra G, Zoroddu S, De Luca A, Bagella L. Nutraceuticals in Pregnancy: A Special Focus on Probiotics. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:9688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Jarde A, Lewis-Mikhael AM, Moayyedi P, Stearns JC, Collins SM, Beyene J, McDonald SD. Pregnancy outcomes in women taking probiotics or prebiotics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Liu AT, Chen S, Jena PK, Sheng L, Hu Y, Wan YY. Probiotics Improve Gastrointestinal Function and Life Quality in Pregnancy. Nutrients. 2021;13:3931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Sanders ME. Probiotics: definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46 Suppl 2:S58-S61; discussion S144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Ouyang Q, Xu Y, Ban Y, Li J, Cai Y, Wu B, Hao Y, Sun Z, Zhang M, Wang M, Wang W, Zhao Y. Probiotics and Prebiotics in Subclinical Hypothyroidism of Pregnancy with Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth. Probiotics Antimicrob Proteins. 2024;16:579-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Halkjær SI, Refslund Danielsen M, de Knegt VE, Andersen LO, Stensvold CR, Nielsen HV, Mirsepasi-Lauridsen HC, Krogfelt KA, Cortes D, Petersen AM. Multi-strain probiotics during pregnancy in women with obesity influence infant gut microbiome development: results from a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2337968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Hrnciarova J, Kubelkova K, Bostik V, Rychlik I, Karasova D, Babak V, Datkova M, Simackova K, Macela A. Modulation of Gut Microbiome and Autism Symptoms of ASD Children Supplemented with Biological Response Modifier: A Randomized, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Nutrients. 2024;16:1988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Sharon G, Cruz NJ, Kang DW, Gandal MJ, Wang B, Kim YM, Zink EM, Casey CP, Taylor BC, Lane CJ, Bramer LM, Isern NG, Hoyt DW, Noecker C, Sweredoski MJ, Moradian A, Borenstein E, Jansson JK, Knight R, Metz TO, Lois C, Geschwind DH, Krajmalnik-Brown R, Mazmanian SK. Human Gut Microbiota from Autism Spectrum Disorder Promote Behavioral Symptoms in Mice. Cell. 2019;177:1600-1618.e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 670] [Cited by in RCA: 817] [Article Influence: 116.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (16)] |

| 104. | Zhang L, Bang S, He Q, Matsuda M, Luo X, Jiang YH, Ji RR. SHANK3 in vagal sensory neurons regulates body temperature, systemic inflammation, and sepsis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1124356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Sgritta M, Dooling SW, Buffington SA, Momin EN, Francis MB, Britton RA, Costa-Mattioli M. Mechanisms Underlying Microbial-Mediated Changes in Social Behavior in Mouse Models of Autism Spectrum Disorder. Neuron. 2019;101:246-259.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 527] [Cited by in RCA: 607] [Article Influence: 86.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Bonaz B, Bazin T, Pellissier S. The Vagus Nerve at the Interface of the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 425] [Cited by in RCA: 878] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Longo S, Rizza S, Federici M. Microbiota-gut-brain axis: relationships among the vagus nerve, gut microbiota, obesity, and diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2023;60:1007-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 108. | Zhang R, Jia MX, Zhang JS, Xu XJ, Shou XJ, Zhang XT, Li L, Li N, Han SP, Han JS. Transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation in children with autism and its impact on plasma levels of arginine-vasopressin and oxytocin: a prospective single-blinded controlled study. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:1136-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/