Published online Nov 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.108797

Revised: July 23, 2025

Accepted: August 21, 2025

Published online: November 19, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 19.7 Hours

First-time mothers may encounter various problems during postpartum, which can result in negative emotions that can affect infant care. In today’s Internet era, continuous nursing services can be provided to mothers and their babies after delivery through Internet-based platforms. This approach can help reduce nega

To explore the effect of Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services on postpartum depression of primiparas and neonatal growth and development and thus provide a scientific basis for strengthening postpartum healthcare measures and better protect maternal and child health.

The study retrospectively collected data of primiparas and their newborns who underwent prenatal examination and successfully delivered at the Ninth People’s Hospital of Suzhou City. The observation group included 30 primiparas and their newborns who received Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services be

Upon hospital discharge, the two groups did not demonstrate significant differences in maternal role adaptation scores, breastfeeding rates, EPDS scores, as well as newborn height, head circumference, and weight at birth (P > 0.05). At the 6-week postpartum follow-up, the maternal role adaptation score and breastfeeding rate were higher in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05). In addition, one case of postpartum depression was reported in the observation group and eight in the control group. Moreover, the control group exhibited a signi

Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services improve maternal role adaptation, increase breastfeeding rates, mitigate postpartum depression risk, and promote neonatal growth and development in primiparas.

Core Tip: Primiparas are at a higher risk of experiencing postpartum depression, which can negatively affect the growth and development of their newborns owing to their limited parenting experience. This study focuses on the introduction of Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services to effectively improve maternal role adaptation and increase breastfeeding rates among primiparas. This approach was found to positively contribute to reducing postpartum depression and promoting neonatal growth and development.

- Citation: Wu TT, Shen WY, Chen LH, Cao BL, Xu CY, Fang Y. Effect of Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services on postpartum depression of primipara and growth and development of neonates. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(11): 108797

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i11/108797.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.108797

During puerperium, the maternal physiology remarkably changes, along with changes in psychological adaptation characteristics, physical recovery following delivery, and considerations related to infant care, breastfeeding, etc. Women who do not receive scientific and reasonable treatments and postpartum healthcare services following delivery are often prone to anxiety, irritability, depression, and other negative emotions, which in turn increases the risk of postpartum depression[1]. Relevant studies have shown that postpartum depression affects not only the mental health of mothers but also the quality of life, interpersonal relationships, and social function of mothers[2], which contributes to the inability of mothers to effectively take care of their newborns and affects the normal development of the newborn’s emotions, cognition, and behavior[3]. Another study showed that severe postpartum depression can lead to hallucinations, suicide, or infanticide, which have negative effects on family and social stability[4]. At present, China’s postpartum healthcare services are mainly based on health education before hospital discharge, supplemented by regular telephone follow-up (such as asking about the status of mothers and newborns and giving corresponding guidance and suggestions). This model lacks the necessary binding force on maternal self-behavior, resulting in poor outcomes. Therefore, further examination on ways to enhance and ensure effective postpartum healthcare services for both mothers and infants is necessary, as this is an important strategy for preventing postpartum depression and promoting neonatal growth and development. After successful delivery, mothers are usually discharged as soon as possible to rest at home. Conse

This retrospective study enrolled primiparas who received antenatal care and delivered without complications at Suzhou Ninth People’s Hospital, along with their neonates. Beginning in July 2024, our hospital implemented the Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare service for mothers and infants. Thirty primiparas and their neonates receiving this intervention between July and December 2024 were selected as the observation group. Following the matched (1:1) case-control study principle, 30 primiparas and their neonates receiving routine postpartum care between January and June 2024 were assigned to the control group.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Primiparas age ≥ 18 years; (2) Singleton pregnancy and full-term delivery; (3) Ability to read, write, and communicate; (4) Living in the city or the surrounding area of the city and have access to Internet services; (5) Discharge from hospital 3-4 days after delivery; and (6) Provision of informed and signed consent.

Exclusion criteria: (1) A history of mental illness; (2) Diagnosis with depression before delivery; (3) A history of mental illness in direct relatives; (4) Physical disability; (5) Medical disputes with hospitals; (6) Unclear questionnaire content and inability to fill out the questionnaire; (7) Serious deformity in the newborn; and (8) Presence of serious postpartum complications, such as postpartum hemorrhage and infection.

The control group received routine postpartum healthcare services. Nursing staff provides routine health education to postpartum women before hospital discharge, such as postpartum exercise guidance, medication guidance, psychological counseling, breastfeeding guidance, newborn health guidance, and primary caregiver health education. Moreover, they verify the information of the parturient, conduct regular telephone follow-up after the hospital discharge, inquire about the current situation of the parturient and newborn, patiently answer any questions that the parturient may have during the recovery period, and provide guidance and suggestions based on the situation. If the problem cannot be solved through telephone communication, the nursing staff instructs the parturient to return to the hospital for reexamination as soon as possible.

The observation group also received Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services in addition to the routine postpartum healthcare services. Specifically: (1) The extended obstetric service system offers access to “medical care and online consultations”. It supports various applications, such as WeChat public account, Alipay, and mini-programs, creating a user service entry according to the actual needs of the project; (2) After delivery, the puerpera is encouraged to input her personal information into the platform, including her health status and family circumstances. This allows the hospital to gain insight into her specific needs and promptly deploy nursing staff familiar with those needs and provide on-site nursing services, maternal and child care, health education, and other services for the puerpera, her family, and newborn; (3) To ensure that all primiparas continue to receive better postpartum nursing services after discharge, the obstetric extension service system platform disseminates weekly information on postpartum depression, postpartum nursing and rehabilitation, neonatal feeding and nursing care, common neonatal diseases and nursing care, and the interaction between the parturient and her newborn. The information was combined into an engaging popular science essay using both text and pictures, allowing mothers to understand and access postpartum healthcare at any time; and (4) The platform also outlines the specific charging standards of the on-site service items provided by the nursing staff. Parturients choose nursing services according to their actual needs, such as care for postpartum perineal wound care, perineal suture removal, lactation support, neonatal jaundice detection, neonatal foot blood collection, neonatal umbilical disinfection care, and neonatal bathing. Upon receiving the maternal request order, the postpartum healthcare service department first evaluates the maternal information and then sends the order. After receiving the order, the obstetric medical staff promptly provides on-site services. During this process, the staff inquire about the mother’s wound healing and uterine contractions, outline postpartum precautions to prevent postpartum complications, explain the benefits of breastfeeding, and guide the mother on proper vulval and breast care in her daily routine. Moreover, the staff guide the family members in assisting the primipara with standardized breastfeeding techniques, help them master baby-holding postures, lactation skills, feeding methods, neonatal bathing, skin care, umbilical care, and diaper replacement. This support can boost the confidence of the primipara in feeding her baby and ensure the healthy growth and development of the newborn. The staff also encourages increased communication between family members and primiparas, allowing them to feel the support of their families. Moreover, family members and primiparas are encouraged to watch children’s songs and dances and parent-child programs together to strengthen their bonds and help primiparas in transitioning to a new role. In addition, for mothers experiencing negative emotions or those lacking parenting knowledge, postpartum health care service personnel should provide psychological counseling, patiently listen to their concerns, and actively help them alleviate negative emotions.

(1) General data collection: A general data sheet was used to collect maternal age, education level, place of residence, mode of delivery, pregnancy complications (such as gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes), neonatal sex, and other related information; (2) Maternal role adaptation: The maternal role adaptation questionnaire was used to assess primiparas upon hospital discharge and 6 weeks after delivery. The questionnaire included role cognition, care behavior, and parent-child attachment, with a total of three dimensions and 16 items. A 5-level Likert (1-5 points) scoring method was used. The total questionnaire score was 16-80 points: The higher the score, the higher the maternal role adaptation; (3) Breastfeeding rate: The exclusive breastfeeding rates at discharge and 6 weeks postpartum were compared; (4) Eva

IBM SPSS version 25.0 was used for data analysis. The measurement data were first confirmed to conform to the normal distribution by the Shapiro-Wilk method, expressed as mean ± SD, and the two groups were compared by the indepen

No significant difference was found in the baseline data of age, education level, place of residence, mode of delivery, pregnancy complications, neonatal sex, and neonatal birth length, head circumference, and birth weight between the two groups (P > 0.05; Table 1).

| Baseline information | Control group (n = 30) | Observers group (n = 30) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Age (years), mean ± SD | 26.43 ± 2.76 | 26.92 ± 2.98 | 0.661 | 0.511 |

| Standard of culture | 0.071 | 0.791 | ||

| High school and below | 11 (36.67) | 12 (40.00) | ||

| College or higher | 19 (63.33) | 18 (60.00) | ||

| Place of abode | 0.067 | 0.796 | ||

| Cities and towns | 14 (46.67) | 15 (50.00) | ||

| Rural district | 16 (53.33) | 15 (50.00) | ||

| Delivery method | 0.341 | 0.559 | ||

| Natural birth | 23 (76.67) | 21 (70.00) | ||

| Caesarean birth | 7 (23.33) | 9 (30.00) | ||

| Pregnancy complications | 0.577 | 0.448 | ||

| Not have | 3 (10.00) | 5 (16.67) | ||

| Have | 27 (90.00) | 25 (83.33) | ||

| Gender of newborn | 0.069 | 0.793 | ||

| Male baby | 17 (56.67) | 18 (60.00) | ||

| Female infant | 13 (43.33) | 12 (40.00) |

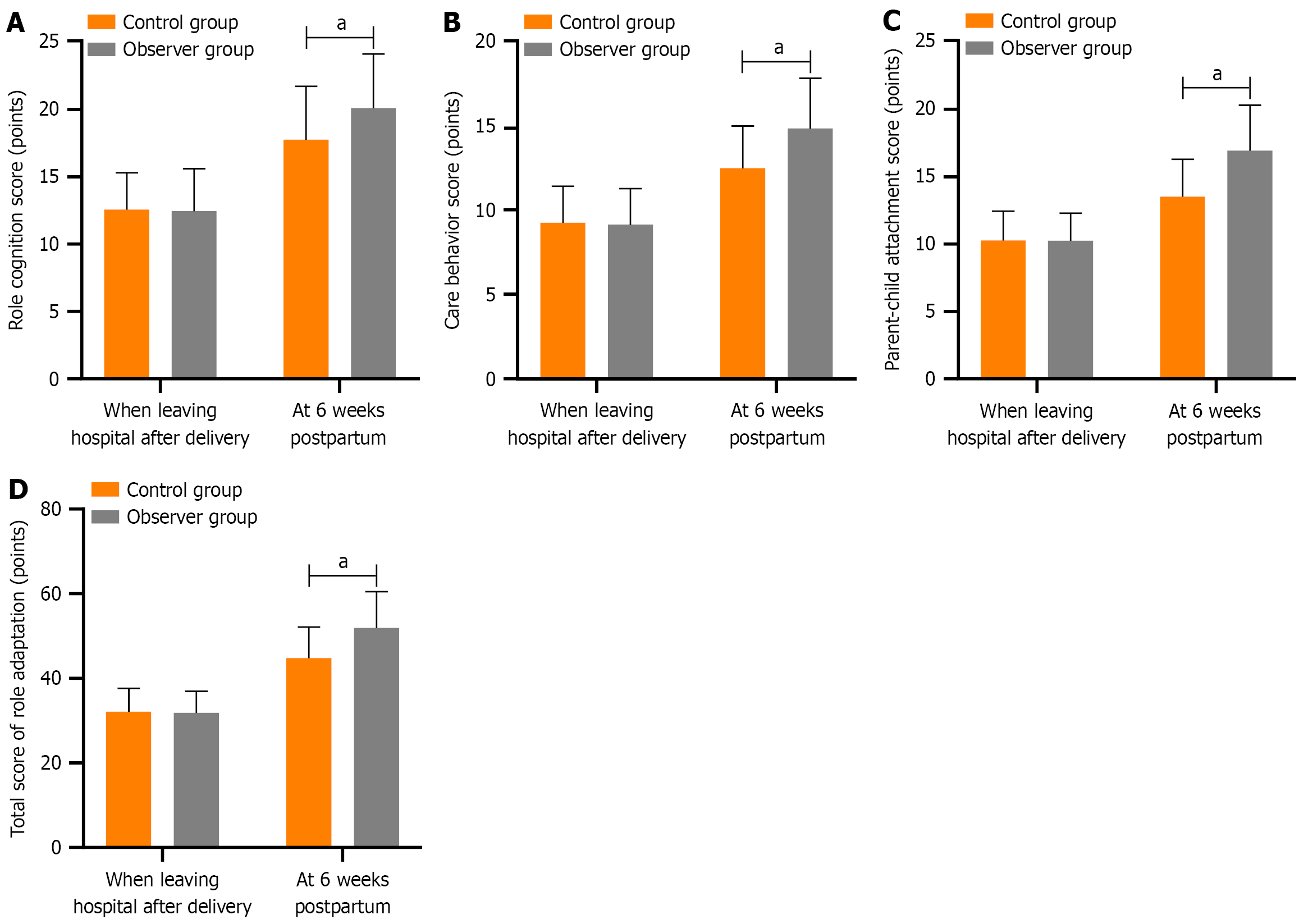

No significant difference was noted in the role cognition, care behavior, parent-child attachment, and total scores of role adaptation between the two groups on hospital discharge (P > 0.05). At the 6-week postpartum follow-up, the observa

| Index (point) | Stage | Control group (n = 30) | Observers group (n = 30) | t value | P value |

| Role cognition score | When leaving hospital after delivery | 12.58 ± 2.74 | 12.45 ± 3.16 | 0.170 | 0.865 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 17.75 ± 3.98a | 20.11 ± 4.02a | 2.285 | 0.026 | |

| Care behavior score | When leaving hospital after delivery | 9.24 ± 2.16 | 9.12 ± 2.13 | 0.217 | 0.829 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 12.47 ± 2.51a | 14.83 ± 2.96a | 3.331 | 0.002 | |

| Parent-child attachment score | When leaving hospital after delivery | 10.29 ± 2.15 | 10.25 ± 2.07 | 0.073 | 0.941 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 13.54 ± 2.76a | 16.94 ± 3.38a | 3.012 | 0.004 | |

| Total score of role adaptation | When leaving hospital after delivery | 32.11 ± 5.54 | 31.82 ± 5.17 | 0.209 | 0.835 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 44.76 ± 7.43a | 51.88 ± 8.59a | 3.434 | 0.001 |

No significant difference was found in the exclusive breastfeeding rates between the two groups upon discharge after delivery (P > 0.05). At the 6-week postpartum follow-up, the exclusive breastfeeding rate was significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05; Table 3).

| Index | stage | Control group (n = 30) | Observers group (n = 30) | χ2 value | P value |

| Exclusive breastfeeding rate | When leaving hospital after delivery | 14 (46.67) | 13 (43.33) | 1.071 | 0.301 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 18 (60.00) | 26 (86.67) | 5.455 | 0.020 |

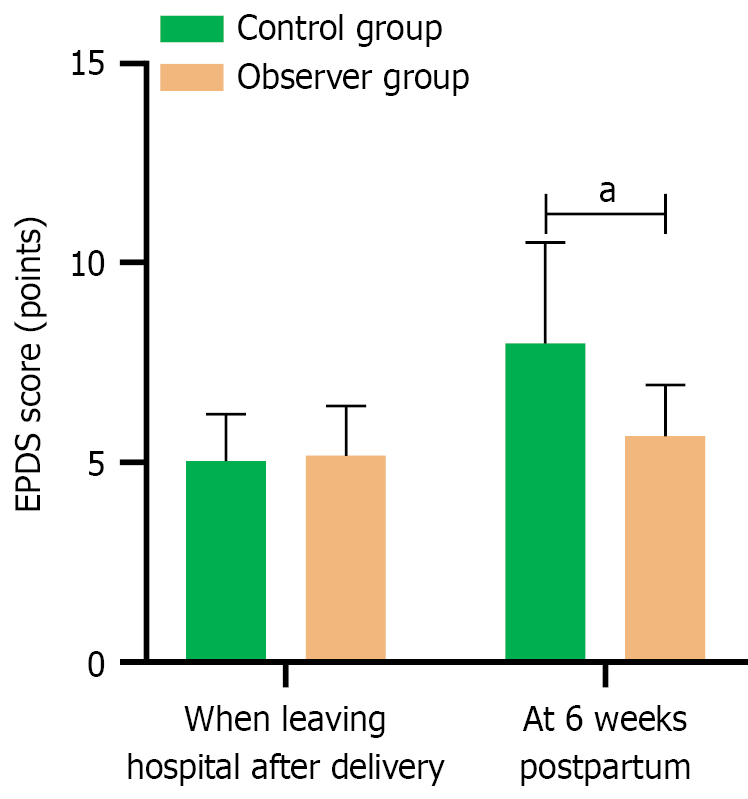

At the time of delivery and discharge, two groups did not show signs of postpartum depression, and the difference in EPDS scores was not significant (P > 0.05). However, at the 6-week postpartum follow-up, one case of postpartum depression was noted in the observation group and eight cases in the control group. The control group exhibited a significant increase in EPDS scores at the 6-week postpartum follow-up compared with scores at hospital discharge (P < 0.05), whereas the observation group showed only a marginal, nonsignificant increase in EPDS scores during the same period (P > 0.05). The EPDS score of the observation group at 6 weeks postpartum was significantly lower than that of the control group (P < 0.001; Table 4, Figure 2).

| Index | Stage | Control group (n = 30) | Observers group (n = 30) | t value | P value |

| EPDS score (points) | When leaving hospital after delivery | 5.03 ± 1.18 | 5.17 ± 1.25 | 0.446 | 0.657 |

| At 6 weeks postpartum | 7.98 ± 2.53a | 5.66 ± 1.28 | 4.482 | < 0.001 |

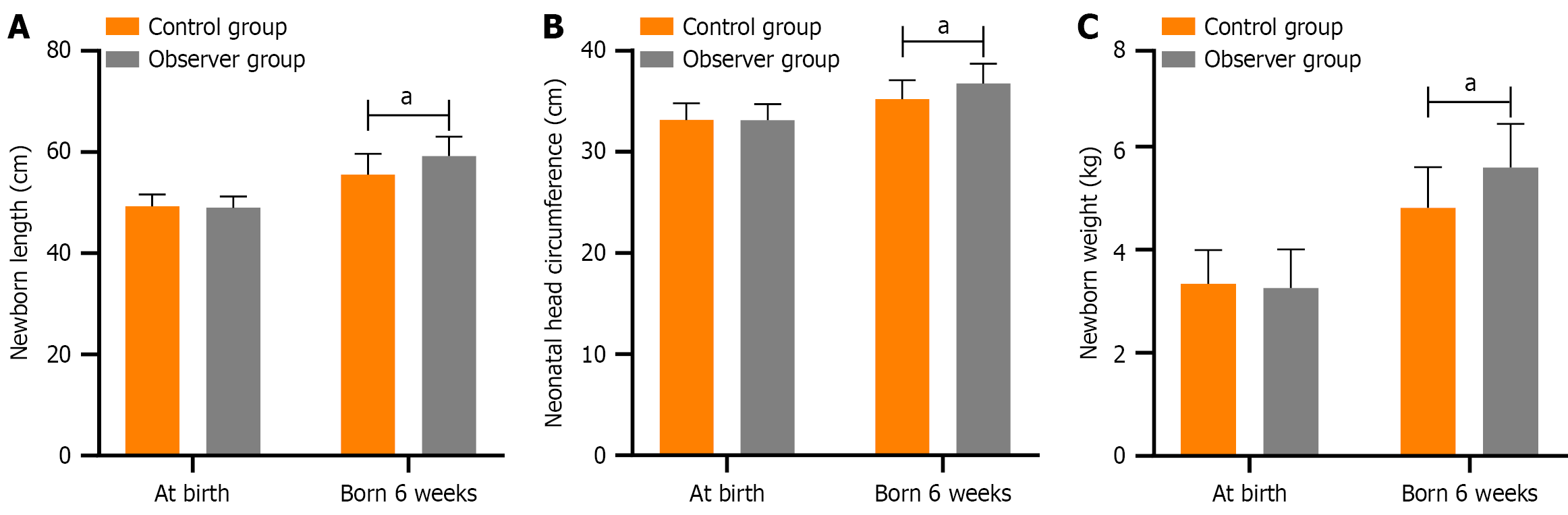

No significant difference was found in neonatal length, head circumference, and weight between the two groups at birth (P > 0.05). At the 6-week follow-up after birth, the length, head circumference, and weight of both groups increased compared with those at birth, and the growth rate of the observation group was greater than that of the control group (P < 0.001; Table 5, Figure 3).

| Index | Stage | Control group (n = 30) | Observers group (n = 30) | t value | P value |

| Neonatal length (cm) | At birth | 49.32 ± 2.28 | 49.05 ± 2.19 | 0.468 | 0.642 |

| Born 6 weeks | 55.54 ± 4.12a | 59.25 ± 3.76a | 3.643 | < 0.001 | |

| Neonatal head circumference (cm) | At birth | 33.15 ± 1.63 | 33.12 ± 1.58 | 0.072 | 0.943 |

| Born 6 weeks | 35.23 ± 1.85a | 36.74 ± 1.98a | 3.052 | 0.003 | |

| Birth weight (kg) | At birth | 3.34 ± 0.65 | 3.26 ± 0.74 | 0.445 | 0.658 |

| Born 6 weeks | 4.81 ± 0.79a | 5.59 ± 0.85a | 3.682 | < 0.001 |

Postpartum women experience a decline in estrogen and progesterone levels, reduced catecholamine secretion, and endocrine imbalances, which can lead to emotional instability and delay postpartum recovery[8]. In particular, pri

Most puerperium women expect that care teams continuously offer professional guidance on parenting and self-care during the postpartum period[13]. Therefore, assisting primiparas in strengthening the mother-infant bond and addressing negative emotions can have a lasting positive effect on the well-being of mothers and the growth and development of newborns[14]. In this study, the role cognition, caregiving behavior, parent-child attachment score, and overall role adaptation scores of the observation group were higher than those of the control group at the 6-week postpartum follow-up. This indicates that primiparas receive postpartum health care services, with the help of Internet Plus to build an obstetric extension service system framework that can help provide maternal and infant postpartum healthcare services, ensuring the delivery of effective postpartum healthcare services for primiparas. For example, by utilizing the Internet Plus platform, we can share popular science essays that feature a combination of words and images, such as interactions between mothers and their newborns. This provides primiparas access to essential information during the postpartum period, thereby strengthening the bond between mothers and their newborns and aiding them in their adjustment to motherhood[15].

Moreover, compared with the control group, the observation group had a significantly higher exclusive breastfeeding rate at 6 weeks postpartum. This may be attributed to the Internet Plus-based postnatal healthcare services, which not only highlight the importance of early mother-baby contact but also promote the benefits of exclusive breastfeeding for both newborns and mothers. Consequently, mothers are likely to gain confidence in exclusive breastfeeding and actively engage in exclusive breastfeeding[16].

Through the platform, mothers can also seek online consultations on newborn diseases and care, feeding practices, and other related topics, which can alleviate the anxiety of those having difficulty obtaining information on newborn health. Andreu-Pejó et al[17] showed that utilizing the Internet to understand maternal emotional status can help in alleviating maternal negative emotions. In this study, only one case of postpartum depression occurred in the observation group at 6 weeks postpartum, whereas eight cases of postpartum depression were recorded in the control group. At 6 weeks postpartum, the EPDS score of the observation group was significantly lower than that of the control group, indicating the effectiveness of the Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services for primiparas. For example, the use of the Internet Plus-based platform to share scientific information related to postpartum depression can reduce, to a certain extent, psychological distress among primiparas. Moreover, through the door-to-door nursing setup, primiparas can request for home care services when they encounter some issues. When a medical staff visits primiparas for in-home care, they can assess maternal wound healing and uterine contractions on-site while addressing maternal and infant problems that primiparas encounter during the postpartum period. This on-site support can effectively reduce maternal worries and anxiety, thereby reducing the risk of postpartum depression. Conversely, routine postpartum healthcare services typically rely on telephone follow-up to provide guidance and suggestions based on maternal demands, which may be challenging for primiparas without parenting experience. The Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare service is mainly based on the demands sent by the mothers through the online platform, and the nursing staff then provides door-to-door nursing care. During the on-site nursing visits, the medical staff can also provide psychological counseling to help the puerpera learn some effective emotional release methods and build their confidence in parenting. By actively helping primiparas alleviate negative emotions, the risk of postpartum depression can be reduced. Many studies have shown that breastfeeding can reduce the risk of postpartum depression[18-20] while supporting the growth and development of newborns. In this study, the length, head circumference, and weight of newborns in the observation group were sig

This study has some limitations. Although this study found that Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services have a positive effect on reducing postpartum depression and promoting the growth and development of newborns, this is a single-center retrospective study analyzing a small sample. Thus, it may not fully represent different populations. Therefore, future studies are encouraged to analyze a large sample and conduct multicenter prospective analysis to further verify the findings of this study.

Internet Plus-based postpartum healthcare services can improve the role adaptation of primiparas, increase the breastfeeding rate, promote the growth and development of newborns, and reduce the risk of postpartum depression of parturients.

| 1. | Madeghe BA, Kimani VN, Vander Stoep A, Nicodimos S, Kumar M. Postpartum depression and infant feeding practices in a low income urban settlement in Nairobi-Kenya. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Huang X, Wang Y, Wang Y, Guo X, Zhang L, Wang W, Shen J. Prevalence and factors associated with trajectories of antenatal depression: a prospective multi-center cohort study in Chengdu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2023;23:358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gribbin C, Achieng F, K'Oloo A, Barsosio HC, Kwobah E, Kariuki S, Nabwera HM. Exploring the influence of postnatal depression on neonatal care practices among mothers in Western Kenya: A qualitative study. Womens Health (Lond). 2023;19:17455057231189547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hu Y, Wang Y, Wen S, Guo X, Xu L, Chen B, Chen P, Xu X, Wang Y. Association between social and family support and antenatal depression: a hospital-based study in Chengdu, China. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ngai FW, Chan SW, Holroyd E. Chinese primiparous women's experiences of early motherhood: factors affecting maternal role competence. J Clin Nurs. 2011;20:1481-1489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang CJ, Han W, Huang CQ. Effect of Internet + continuous midwifery service model on psychological mood and pregnancy outcomes for women with high-risk pregnancies. World J Psychiatry. 2023;13:862-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu J, Zhang Z, Deng Y, Zhang L, He C, Wu Y, Xu X, Yang J. Risk factors for the development of postpartum depression in individuals who screened positive for antenatal depression. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Modak A, Ronghe V, Gomase KP, Mahakalkar MG, Taksande V. A Comprehensive Review of Motherhood and Mental Health: Postpartum Mood Disorders in Focus. Cureus. 2023;15:e46209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Slomian J, Honvo G, Emonts P, Reginster JY, Bruyère O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: A systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health (Lond). 2019;15:1745506519844044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 110.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hassan BK, Werneck GL, Hasselmann MH. Maternal mental health and nutritional status of six-month-old infants. Rev Saude Publica. 2016;50:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu CC, Chen YC, Yeh YP, Hsieh YS. Effects of maternal confidence and competence on maternal parenting stress in newborn care. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68:908-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Talebi F, Javadifar N, Simbar M, Dastoorpoor M, Shahbazian N, Abbaspoor Z. Effect of the Parenting Preparation Program on Maternal Role Competence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. 2023;28:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Woodward BM, Zadoroznyj M, Benoit C. Beyond birth: Women's concerns about post-birth care in an Australian urban community. Women Birth. 2016;29:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Saharoy R, Potdukhe A, Wanjari M, Taksande AB. Postpartum Depression and Maternal Care: Exploring the Complex Effects on Mothers and Infants. Cureus. 2023;15:e41381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Zhang S, Qian Z, Zhao Y, Yu X, Cheng C, Li Q. Effects of Group Prenatal Health Care Combined with Happiness Training on Delivery Mode and Maternal Role Adaptation in Elderly Primiparous Women: A Study for Improvements in Patients Health Behavior. Am J Health Behav. 2023;47:369-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dessì A, Pianese G, Mureddu P, Fanos V, Bosco A. From Breastfeeding to Support in Mothers' Feeding Choices: A Key Role in the Prevention of Postpartum Depression? Nutrients. 2024;16:2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Andreu-Pejó L, Martínez-Borba V, Osma López J, Suso-Ribera C, Crespo Delgado E. Perinatal mental e-health: What is the profile of pregnant women interested in online assessment of their emotional state? Nurs Open. 2023;10:901-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sha T, Gao X, Chen C, Li L, Cheng G, Wu X, Tian Q, Yang F, He Q, Yan Y. A prospective study of maternal postnatal depressive symptoms with infant-feeding practices in a Chinese birth cohort. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cato K, Sylvén SM, Georgakis MK, Kollia N, Rubertsson C, Skalkidou A. Antenatal depressive symptoms and early initiation of breastfeeding in association with exclusive breastfeeding six weeks postpartum: a longitudinal population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Neupane S, de Oliveira CVR, Palombo CNT, Buccini G. Association between breastfeeding cessation among under six-month-old infants and postpartum depressive symptoms in Nevada. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0297218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alahmed S, Frost S, Fernandez R, Win K, Mutair AA, Harthi MA, Meedya S. Evaluating a woman-centred web-based breastfeeding educational intervention in Saudi Arabia: A before-and-after quasi-experimental study. Women Birth. 2024;37:101635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/