Published online Nov 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.106164

Revised: July 14, 2025

Accepted: August 26, 2025

Published online: November 19, 2025

Processing time: 159 Days and 18 Hours

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) affects millions worldwide, and many patients develop depression and anxiety. The disease’s long-term nature, potential complications, and social stigma contribute to these mental-health issues. However, previous studies on this link differed in their methods and results, making it hard to draw clear conclusions. This study aimed to analyze factors associated with CHB through meta-analysis of previous studies to help improve patients’ mental health.

To systematically search, screen, and comprehensively analyze existing relevant research through meta-analysis of previous studies to assess the correlation of the previously identified factors found to be associated with comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with CHB, with the goal of improving the patients' men

This study strictly adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Re

The study included 14 articles from five countries (China, United States, Turkey, Australia, and Vietnam), in

Multiple factors were significantly associated with comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with CHB. Clinically, it is essential to identify high-risk patients at the earliest opportunity and implement effective in

Core Tip: Patients with chronic hepatitis B may experience a significant burden of mental-health issues, with 30.1% experiencing depression, 40.2% anxiety, and 33.7% overall negative emotions. Higher educational level was a protective factor (odds ratio = 0.43) by enhancing self-management and disease understanding, whereas older age, longer treatment duration, comorbidities, poor sleep quality, emotional instability, frequent hepatitis relapses, and severe hepatitis status all elevated the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety. Clinically, early identification of high-risk groups and targeted interventions, such as education-based counseling and sleep management, are crucial for improving mental-health outcomes, although current research heterogeneity from diverse assessment tools and regional sampling indicates the need for standardized broader population studies in the future.

- Citation: Guo L, He LX, Wan PQ, Zhen XM, Xiao F, Wu WB, Su MH, Gao BH, Liu ZH. Meta-analysis of factors associated with the incidence of comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with chronic hepatitis B. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(11): 106164

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i11/106164.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i11.106164

Chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is prevalent globally. According to the “Global Hepatitis Report 2024” released by the World Health Organization, approximately 254 million people worldwide were chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) in 2022. Severe complications, such as liver failure, liver cirrhosis, and liver cancer caused by HBV, lead to approximately 1.1 million deaths each year, imposing a heavy burden on the public-health field[1,2]. Due to its long-term course, numerous complications, potential infectivity, and risk of carcinogenesis along with the current lack of effective radical treatment methods, patients with CHB potentially experience both damage to their physical functions caused by the disease itself and non-negligible negative emotions and psychological stress[3,4].

Although many studies have investigated the psychological problems of patients with CHB, a study in four provinces in China showed that approximately 75% of patients with CHB experienced discrimination due to HBV infection, causing intense negative emotions and mental stress[5]. Among these, depressive and anxious emotions were particularly prominent. Considering that chronic stress in patients with CHB may elevate cortisol levels and suppress immune function, anxiety and depressive moods might reduce patients’ medication adherence, increasing the likelihood of treatment failure and disease relapse. Furthermore, such psychological states can exacerbate physical symptoms, such as fatigue and pain, causing a vicious cycle of deteriorating quality of life.

However, the studies aimed at identifying factors correlating depression/anxiety with CHB have shown significant heterogeneity. Moreover, different studies had obvious differences in the patient samples with different ages, regions, and disease stages. Research methods have included various means, such as questionnaires, clinical interviews, and laboratory tests, making it difficult to comprehensively analyze and effectively compare different studies. Most studies also have been from single centers, so no multi-center, large-sample comprehensive studies have been conducted. These gaps hinder the translation of evidence into clinical practice, necessitating a systematic synthesis to identify robust risk factors.

The aim of this meta-analysis was to systematically evaluate the associations of demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors with comorbid depression/anxiety in patients with CHB. Using a PICOS framework, the review focused on adults with confirmed CHB (excluding special populations), compared risk/protective factor presence, and synthesized data from cohort/case-control/cross-sectional studies.

This meta-analysis systematically evaluated the associations of demographic, clinical, and psychosocial factors with comorbid depression/anxiety in adult patients with CHB. The overall goal was to provide strong evidence useful for clinically identifying high-risk patients with comorbid depression and anxiety and for formulating targeted intervention measures, with the expectation of improving the mental health of patients with CHB, enhancing the quality of life, and optimizing the overall disease management and treatment outcomes of patients with CHB.

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement. Relevant studies on CHB complicated with depression and anxiety were retrieved from English databases, including those of PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library. The retrieval period for each database was from its inception to January 2025.

The retrieval method combined medical subject headings with free terms, supplemented by literature tracing. The search terms were: “Hepatitis B”, “Chronic”, “Hepatitis B Virus Infection”, “Chronic”, “Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection”, “Chronic Hepatitis B”, “Anxiety”, “Angst”, “Nervousness”, “Hypervigilance”, “Social Anxiety”, “Anxieties”, “Social”, “Anxiety”, “Social”, “Social Anxieties”, “Anxiousness”, “Depression”, “Depressive Symptoms”, “Depressive Symptom”, “Symptom”, “Depressive”, “Emotional Depression”, “Depression”, “Emotional”, “Risk Factors”, “Factor”, “Risk”, “Risk Factor”, “Population at Risk”, “Populations at Risk”, “Risk Scores”, “Risk Score”, “Score”, “Risk”, “Risk Factor Scores”, “Risk Factor Score”, “Score”, “Risk Factor”, “Health Correlates”, “Correlates”, “Health”, “Social Risk Factors”, “Factor”, “Social Risk”, “Factors”, “Social Risk”, “Risk Factor”, “Social”, “Risk Factors”, “Social”, and “Social Risk Factor”. The detailed retrieval strategies for each database are shown in Table 1.

| Database | Retrieval formula |

| PubMed | ((((((((("Emotions"[Mesh]) OR (Emotion[Title/Abstract])) OR (Feelings[Title/Abstract])) OR (Feeling[Title/Abstract])) OR (Regret[Title/Abstract])) OR (Regrets[Title/Abstract])) OR ((((((((((((((("Psychology"[Mesh]) OR (Psychological Factors[Title/Abstract])) OR (Factor, Psychological[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychological Factor[Title/Abstract])) OR (Factors, Psychological[Title/Abstract])) OR (Side Effects, Psychological[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychological Side Effect[Title/Abstract])) OR (Side Effect, Psychological[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychological Side Effects[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychologists[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychologist[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychosocial Factors[Title/Abstract])) OR (Factor, Psychosocial[Title/Abstract])) OR (Factors, Psychosocial[Title/Abstract])) OR (Psychosocial Factor[Title/Abstract]))) OR (((((("Depression"[Mesh]) OR (Depressive Symptoms[Title/Abstract])) OR (Depressive Symptom[Title/Abstract])) OR (Symptom, Depressive[Title/Abstract])) OR (Emotional Depression[Title/Abstract])) OR (Depression, Emotional[Title/Abstract]))) OR (((((((((("Anxiety"[Mesh]) ) OR (Angst[Title/Abstract])) OR (Nervousness[Title/Abstract])) OR (Hypervigilance[Title/Abstract])) OR (Social Anxiety[Title/Abstract])) OR (Anxieties, Social[Title/Abstract])) OR (Anxiety, Social[Title/Abstract])) OR (Social Anxieties[Title/Abstract])) OR (Anxiousness[Title/Abstract]))) AND (((("Hepatitis B, Chronic"[Mesh]) OR (Hepatitis B Virus Infection, Chronic[Title/Abstract])) OR (Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection[Title/Abstract])) OR (Chronic Hepatitis B[Title/Abstract])) |

| Web of science | (TS=(Psychology OR Psychological Factors OR Factor Psychological OR Psychological Factor OR Factors Psychological OR Side Effects Psychological OR Psychological Side Effect OR Side Effect Psychological OR Psychological Side Effects OR Psychologists OR Psychologist OR Psychosocial Factors OR Factor Psychosocial OR Factors Psychosocial OR Psychosocial Factor) And TS=(Depression OR Depressive Symptoms OR Depressive Symptom OR Symptom Depressive OR Emotional Depression OR Depression Emotional) And TS=(Anxiety OR Angst OR Nervousness OR Hypervigilance OR Social Anxiety OR Anxieties Social OR Anxiety Social OR Social Anxieties OR Anxiousness OR Emotions OR Emotion OR Feelings OR Feeling OR Regret OR Regrets) And TS=(Risk Factors OR Factor Risk OR Risk Factor OR Population at Risk OR Populations at Risk OR Risk Scores OR Risk Score OR Score Risk OR Risk Factor Scores OR Risk Factor Score OR Score Risk Factor OR Health Correlates OR Correlates Health OR Social Risk Factors OR Factor Social Risk OR Factors Social Risk OR Risk Factor Social OR Risk Factors Social OR Social Risk Factor) And TS=(Hepatitis B Chronic OR Hepatitis B Virus Infection Chronic OR Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection OR Chronic Hepatitis B)) (TS=(Depression OR Depressive Symptoms OR Depressive Symptom OR Symptom Depressive OR Emotional Depression OR Depression Emotional OR Anxiety OR Angst OR Nervousness OR Hypervigilance OR Social Anxiety OR Anxieties Social OR Anxiety Social OR Social Anxieties OR Anxiousness OR Emotions OR Emotion OR Feelings OR Feeling OR Regret OR Regrets) And TS=(Hepatitis B Chronic OR Hepatitis B Virus Infection Chronic OR Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection OR Chronic Hepatitis B)) |

| Cochrane library | Emotions ('Emotion' OR 'Feelings' OR 'Feeling' OR 'Regret' OR 'Regrets'):ti,kw,ab OR Psychology ('Psychological Factors' OR 'Factor, Psychological' OR 'Psychological Factor' OR 'Factors, Psychological' OR 'Side Effects, Psychological' OR 'Psychological Side Effect' OR 'Side Effect, Psychological' OR 'Psychological Side Effects' OR 'Psychologists' OR 'Psychologist' OR 'Psychosocial Factors' OR 'Factor, Psychosocial' OR 'Factors, Psychosocial' OR 'Psychosocial Factor'):ti,kw,ab OR Depression ('Depressive Symptoms' OR 'Depressive Symptom' OR 'Symptom, Depressive' OR 'Emotional Depression' OR 'Depression, Emotional') OR Anxiety ('Angst' OR 'Nervousness' OR 'Hypervigilance' OR 'Social Anxiety' OR 'Anxieties, Social' OR 'Anxiety, Social' OR 'Social Anxieties' OR 'Anxiousness') AND Hepatitis B, Chronic ('Hepatitis B Virus Infection, Chronic' OR 'Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection' OR 'Chronic Hepatitis B'):ti,kw,ab |

| Database | EMBASE |

| Retrieval formula | Emotions: 'Emotion':ab,kw,ti OR 'Feelings':ab,kw,ti OR 'Feeling':ab,kw,ti OR 'Regret':ab,kw,ti OR 'Regrets':ab,kw,ti; Psychology: 'Psychological Factors':ab,kw,ti OR 'Factor, Psychological':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychological Factor':ab,kw,ti OR 'Factors, Psychological':ab,kw,ti OR 'Side Effects, Psychological':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychological Side Effect':ab,kw,ti OR 'Side Effect, Psychological':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychological Side Effects':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychologists':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychologist':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychosocial Factors':ab,kw,ti OR 'Factor, Psychosocial':ab,kw,ti OR 'Factors, Psychosocial':ab,kw,ti OR 'Psychosocial Factor':ab,kw,ti; Depression: 'Depressive Symptoms':ab,kw,ti OR 'Depressive Symptom':ab,kw,ti OR 'Symptom, Depressive':ab,kw,ti OR 'Emotional Depression':ab,kw,ti OR 'Depression, Emotional':ab,kw,ti; Anxiety: 'Angst':ab,kw,ti OR 'Nervousness':ab,kw,ti OR 'Hypervigilance':ab,kw,ti OR 'Social Anxiety':ab,kw,ti OR 'Anxieties, Social':ab,kw,ti OR 'Anxiety, Social':ab,kw,ti OR 'Social Anxieties':ab,kw,ti OR 'Anxiousness':ab,kw,ti; Hepatitis B, Chronic: 'Hepatitis B Virus Infection, Chronic':ab,kw,ti OR 'Chronic Hepatitis B Virus Infection':ab,kw,ti OR 'Chronic Hepatitis B' |

Inclusion criteria: (1) Participants: The research subjects were all patients with CHB, excluding newly diagnosed patients and special groups, such as pregnant women, adolescents, students, and children. All subjects were aware of their own medical conditions; (2) Interventions: None (observational studies); (3) Comparisons: Case group: Patients with CHB with comorbid depression and/or anxiety. Control group: Patients with CHB without depression or anxiety; and (4) Outcome: The study should include relevant factors or factors influencing depression or anxiety in patients with CHB. The data of relevant or influencing factors, including the r value, odds ratio (OR), and the 95% confidence interval (95%CI), should be clearly presented or can be calculated.

Study design: Cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. The data analysis of the reviewed study had to have performed Spearman or Pearson correlation analysis or multifactor logistic regression analysis. For patients who had received psychological intervention treatment, the data before treatment should have been used.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Duplicate publications; (2) Non-English literature; (3) Literature with incomplete basic data, a large number of lost-to-follow-up patients, or obviously erroneous data; (4) Low-quality literature with a literature quality evaluation standard of grade C. The reference criteria are shown in the literature inclusion screening and quality evaluation below; and (5) Reviews, conference abstracts, case reports, letters, etc.

A double-blind method was used for the literature screening process. Two researchers independently screened the retrieved literature according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. This step ensured the objectivity and accuracy of the screening process. For the literature that met the inclusion criteria, detailed data extraction was performed, including key information, such as the first author, publication year, research design, sample size, patient age, and relevant factor indicators. During the extraction process, the pre-determined data extraction form was strictly followed to ensure the accuracy and integrity of the data. In case of any disagreement during the screening process, a third researcher would be consulted. Missing data were requested from authors via email.

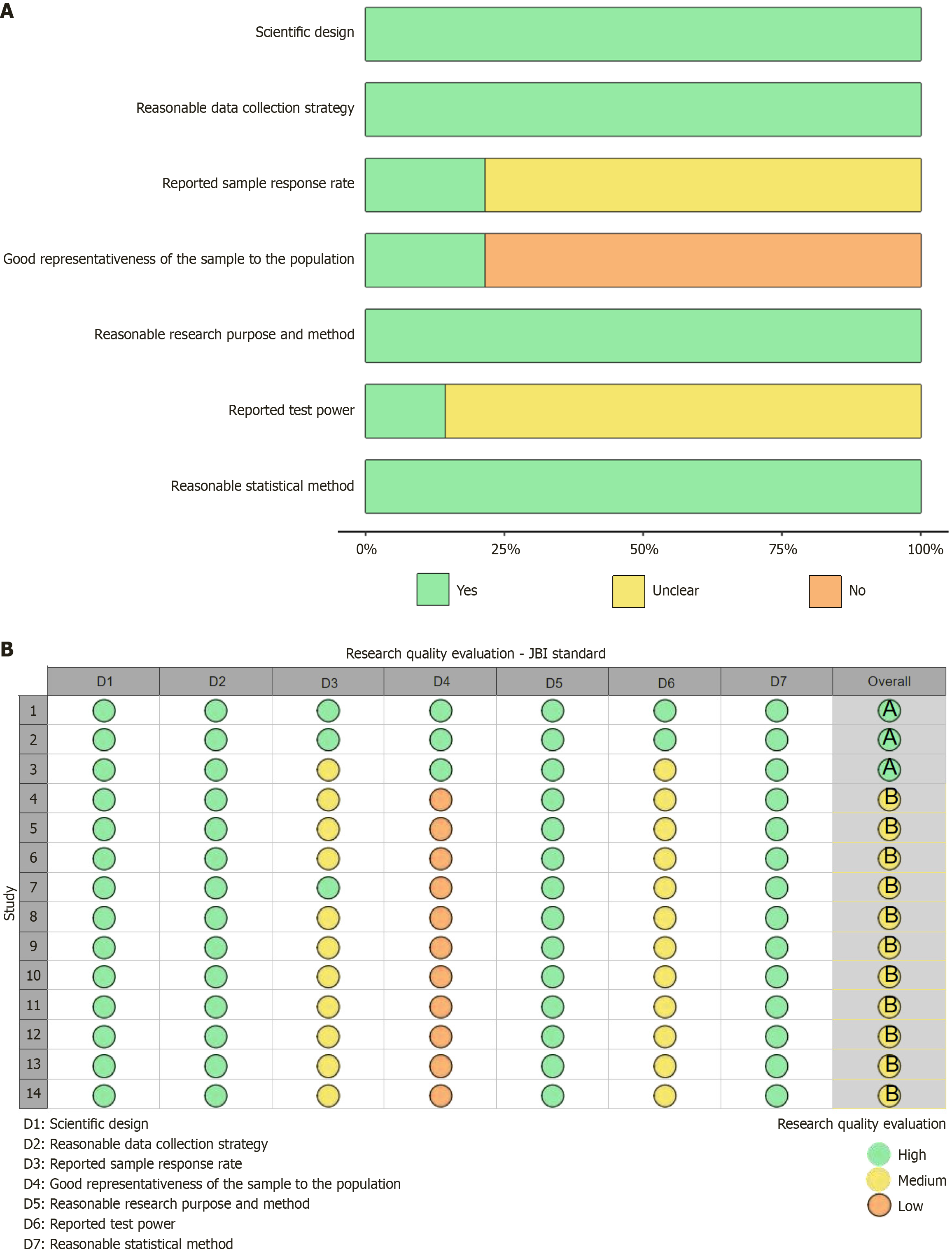

Regarding the quality assessment of the included literature, the cross-sectional quality assessment criteria of the Joanna Briggs Institute Evidence-Based Health Care Research Center in Australia were adopted. These criteria covered various aspects, such as scientific research design, reasonable data collection strategies, reporting of sample response rates, samples that represented the population well, reasonable research objectives and methods, reporting of test power, and reasonable statistical methods. By evaluating these indicators, high reliability and consistency of the quality of the included literature was ensured. During the evaluation process, scoring was conducted strictly in accordance with the evaluation criteria, and a comprehensive quality assessment was made for each piece of literature. For item assessment, 1 point was awarded for low risk, 0.5 points for uncertainty, and 0 points for high-risk. Studies were graded as high (6-7 points), medium (4-5 points), or low (≤ 3 points); low-quality studies (grade C) were excluded. Risk of bias information was used to weight study contributions in the meta-analysis.

STATA12.0 and RevMan 5.3 software were used to perform a meta-analysis of the extracted data. If ≥ 2 articles involved the same correlative factor, the factor was extracted. For dichotomous variable data, the OR and its 95%CI were selected as the effect indicators to evaluate the degree of association between the risk factors of anxiety and depression and the risk of occurrence. The reliability was estimated through the 95%CI, and values of P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

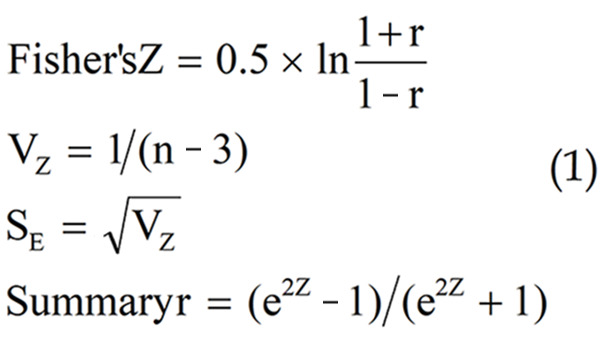

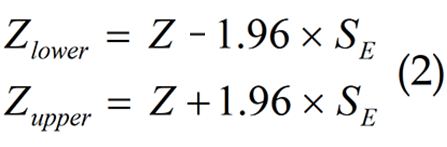

For studies using Pearson correlation analysis, when combining the effect sizes, the correlation coefficient needed to be transformed into Fisher’s Z, as shown in formula (1). For the 95%CI, the lower and upper limits of the value were Zlower and Zupper, respectively, and the 2-sided critical value = 1.96, as shown in formula (2).

Heterogeneity reflects the degree of inconsistency in the results among different studies. The Q-test and I2 were used to evaluate the heterogeneity of the included literature, and the test level was set at α = 0.1. The magnitude of heterogeneity was quantitatively judged by combining it with the I2 statistic. I2 < 50% or P > 0.1 indicated low heterogeneity warranting a fixed-effects model.

I2 ≥ 50% and P ≤ 0.1 indicated substantial heterogeneity requiring a random-effects model. Subgroup analyses by region were performed to explore geographic variation. Sensitivity analyses by sequentially excluding each study were performed to test result robustness. Publication bias was assessed by performing Egger’s test for risk factors with ≥ 10 studies.

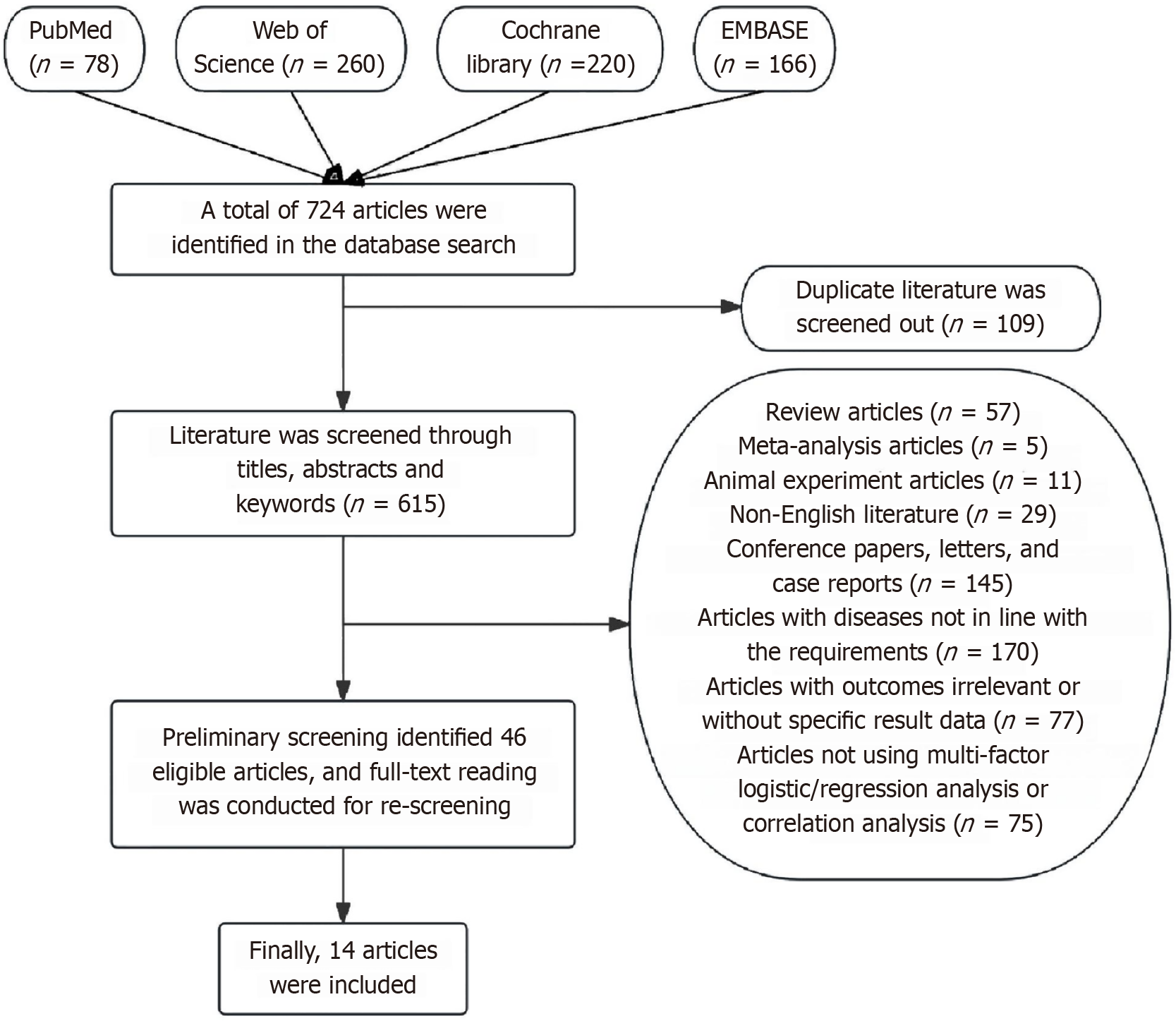

The literature was screened as follows: First, 724 articles were retrieved through database searches in PubMed (n = 78), Web of Science (n = 260), Cochrane Library (n = 220), and EMBASE (n = 166). Subsequently, 109 duplicate articles were removed, leaving 615 articles for screening based on titles, abstracts, and keywords. Consistent with the study’s inclusion criteria, the following article types were excluded: Reviews (n = 57); meta-analyses (n = 5), involved animal experiments (n = 11); not in English (n = 29); conference papers, letters, and case reports (n = 145); were on disease types inconsistent with the requirements (n = 170); had irrelevant outcomes or without specific results data (n = 77); and did not perform multifactor logistic regression analysis or correlation analysis (n = 75). After this initial screening, 46 potentially eligible articles were identified and advanced to the full-text re-screening stage. Finally, a thorough full-text review and re-screening of these 46 articles was performed, and 14 articles were ultimately included for subsequent analysis[6-19]. The results and process of literature screening are summarized in Figure 1. The 14 included articles originated from five countries, China, the United States, Turkey, Australia, and Vietnam, and involved 4494 patients. Among them, 11 articles[2,8-12,14,16-19] reported in detail the incidence of anxiety or depression in patients with CHB. One article only reported the combined incidence of depression and anxiety[6]. Three articles presented the incidence of anxiety and depression in patients with CHB respectively[14,16,17]. Two articles reported the scores of anxiety or depression without providing the specific incidence (Table 2)[13,15].

| Ref. | Country | Study type | Age [(mean ± SD), (min-max), mean (min-max)] | Total sample size | Anxiety incidence (%) | Incidence of depression (%) | Period | Correlation factor |

| Qin et al[6], 2021 | China | Descriptive research | 30-71 | 320 | - | 75 | January 2018 to January 2020 | Education level, duration of treatment, number of relapses, complications, nursing satisfaction |

| Liu et al[7], 2017 | China | Cohort study | 51.5 (37-79) | 501158 | - | 1.09 | 2004-2008 | Male, age, place of residence, household income, occupation |

| Huang et al[8], 2019 | China | Cohort study | 16-70 | 209 | - | 29.20 | June 2017 to May 2018 | Low FT3, total bilirubin |

| Shi et al[9], 2010 | China | Cross-sectional study | 16-68 | 132 | - | 57.60 | 1 June 2007 to 31 December 2007 | Number of relapses, total score of social support, concern about infection, emotional stability, presence or absence of antiviral therapy, hepatitis score |

| Kunkel et al[10], 2000 | America | Cross-sectional study | 24-69 | 50 | - | 46 | September 1998 to December 1998 | Fatigue, serum alanine aminotransferase, serum glutamic oxalacetic aminotransferase |

| Weinstein et al[11], 2011 | America | Retrospective study | 43.6 ± 13.2 | 190 | - | 3.70 | January 2001 to April 2010 | Excessive drinking |

| Hajarizadeh et al[12], 2016 | Australia | Cross-sectional study | 45 (22-77) | 93 | 76 | - | April 2013 to September 2013 | Low level of education, life-changing possibilities |

| Wu et al[13], 2023 | China | Case-control study | - | 747 | - | - | July 2016 to October 2016 | Sleep disorder |

| Ekmen et al[14], 2021 | Türkiye | Cross-sectional study | 40.58 ± 9.12 | 182 | 33.52 | 55.22 | - | Degree of illness, emotional focus |

| Duan et al[15], 2012 | China | Case-control study | 52.40 ± 14.23 | 120 | - | - | July 2009 to July 2010 | Education, mood, hepatitis grading, sleep quality |

| Kong et al[16], 2021 | China | Cross-sectional study | 35.82 (18-66) | 188 | 38.30 | 33.00 | March 2018 to October 2018 | Age, female, education level, duration of treatment |

| Keskin et al[17], 2013 | Türkiye | Cross-sectional study | 47.53 ± 13.79 | 96 | 2.10 | 40.60 | April 2008 to September 2008 | Age, physical function, environment, culture |

| Liu et al[18], 2011 | China | Descriptive research | 37.5 ± 9.3 | 120 | 52.50 | - | September 2008 to March 2010 | CD4+ T cell level, CD4/CD8 ratio |

| Vu et al[19], 2019 | Vietnam | Cross-sectional study | 49.2 ± 16.0 | 298 | 31.40 | 37.50 | October 2018 | CD4+ T cell level, CD4/CD8 ratio |

Among the included articles, 3 articles[6-8] were of high quality, and 11 articles[9-19] were of medium quality (Figure 2A). The specific literature quality evaluation is presented in Figure 2B.

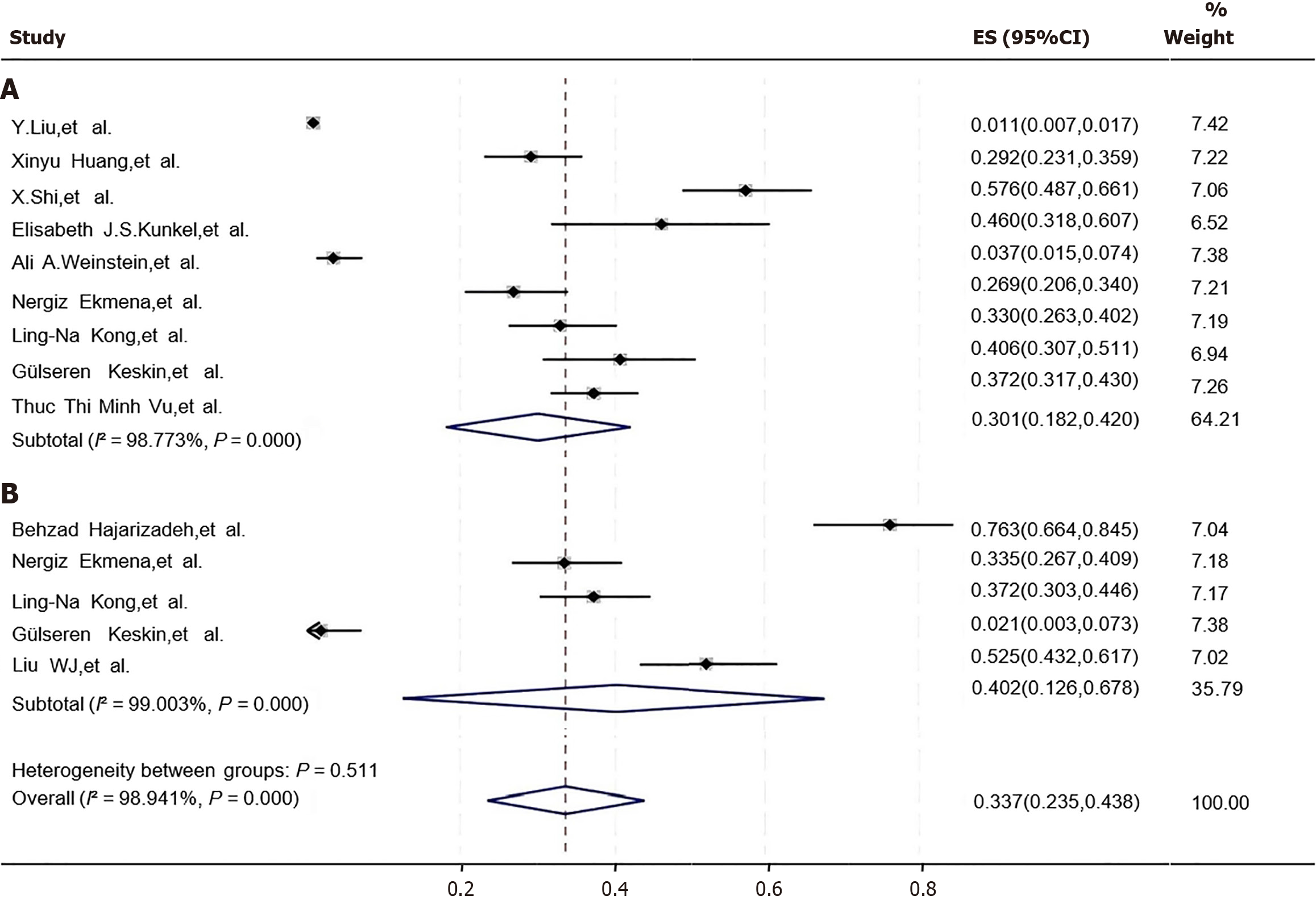

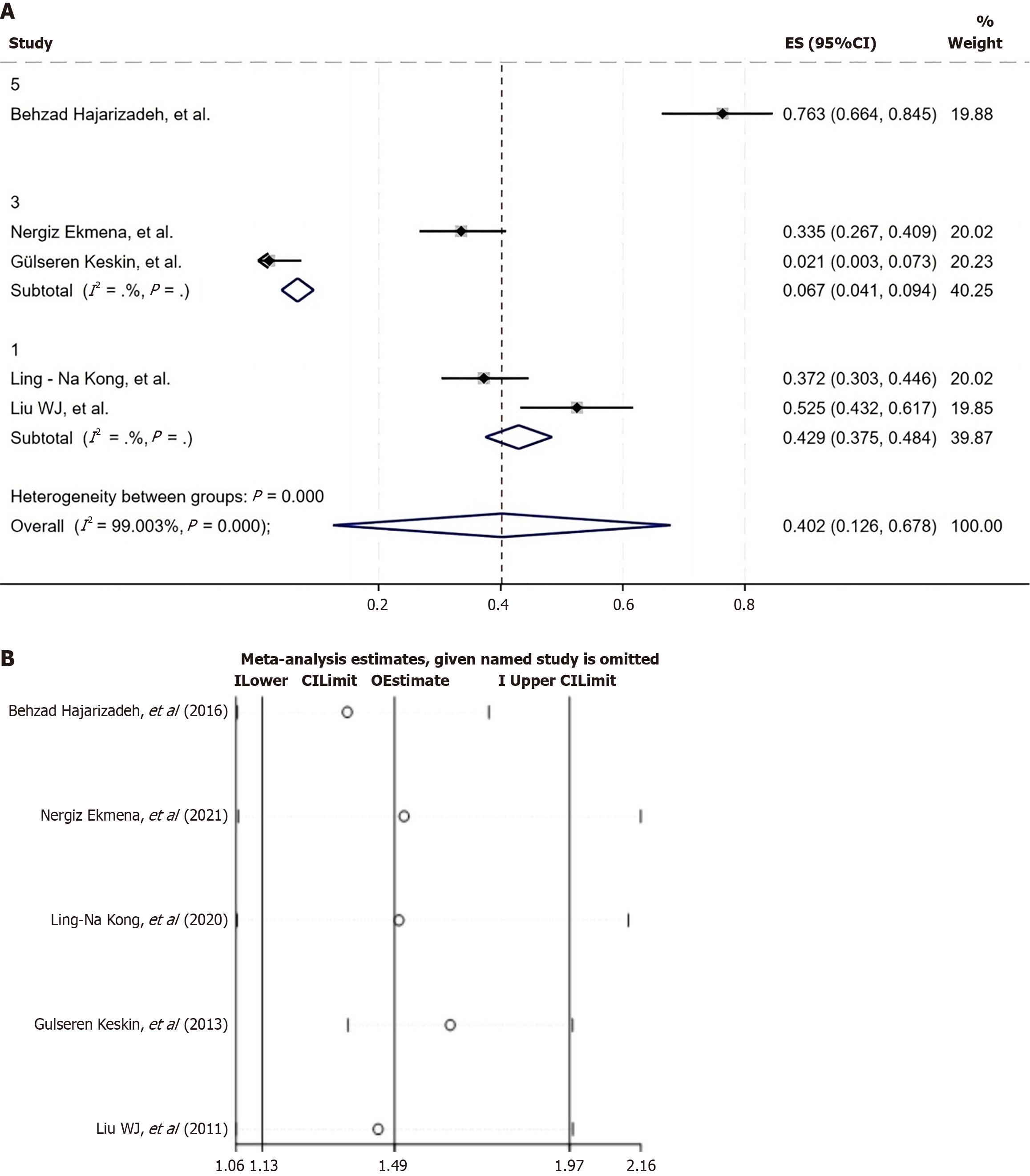

The incidence of comorbid negative emotions (depression or anxiety) in patients with CHB was 33.7% (95%CI: 0.182-0.420; Figure 3A). To investigate the effect of different organ transplants and potential regions on the incidence, this study conducted subgroup analyses according to depression and anxiety, respectively. The results showed that the incidence of comorbid depression in CHB patients was 30.1% (95%CI: 0.182-0.420), and the incidence of comorbid anxiety was 40.2% (95%CI: 0.126-0.678; Figure 3).

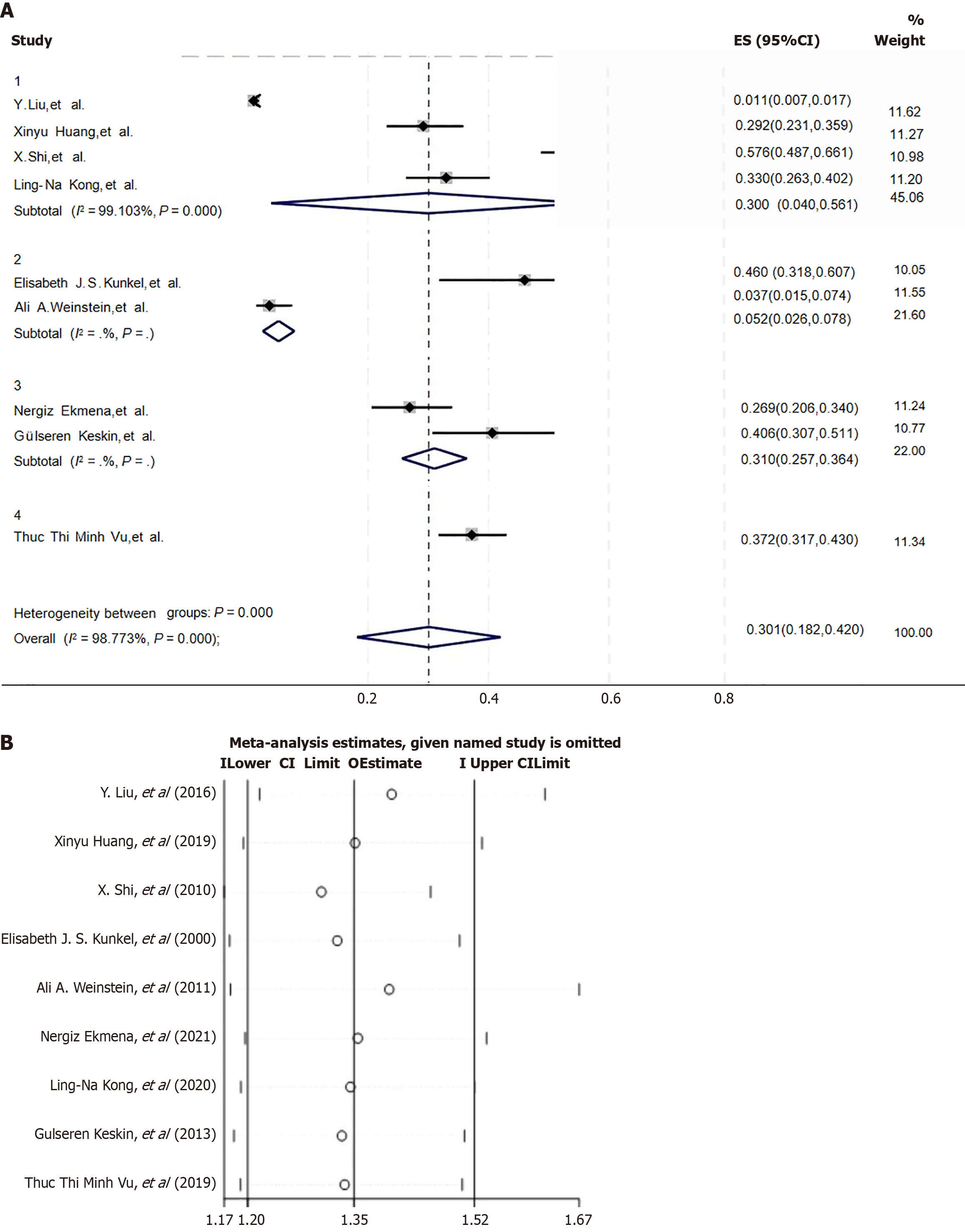

For the subgroup analysis of the incidence of comorbid depression in patients with CHB, among the included studies, the incidences of depression were 30.0%, 5.2%, 31.0%, and 37.2% in Chinese patients with CHB, Australian, Turkish, and Vietnamese, respectively, patients with CHB (Figure 4A). For the sensitivity analysis of the literature on the incidence of comorbid anxiety in patients with CHB, after each article was sequentially excluded, the combined results of the remaining studies all became statistically significant. The meta-analysis results were not prone to significant changes due to the variation in the number of studies, indicating robustness (Figure 4B).

For the subgroup analysis of the incidence of comorbid anxiety in patients with CHB, among the included studies, the incidence of comorbid anxiety was 76.3%, 42.9%, and 6.7% in the Australian, Chinese, and Turkish patients with CHB, respectively (Figure 5A). For the sensitivity analysis of the literature on the incidence of comorbid anxiety in patients with CHB, after each article was sequentially excluded, the combined results of the remaining studies were all statistically significant. The analysis results were robust and not easily affected by the change in the number of studies (Figure 5B).

Through data extraction, the analysis of correlative factors and multivariate analysis of > 2 studies reported eight different risk factors: Educational level, treatment duration, comorbidities, age, sleep quality, emotional stability, number of hepatitis relapses, and degree of hepatitis. Heterogeneity tests were performed on the literature related to these 8 factors, and the combined effect sizes were calculated.

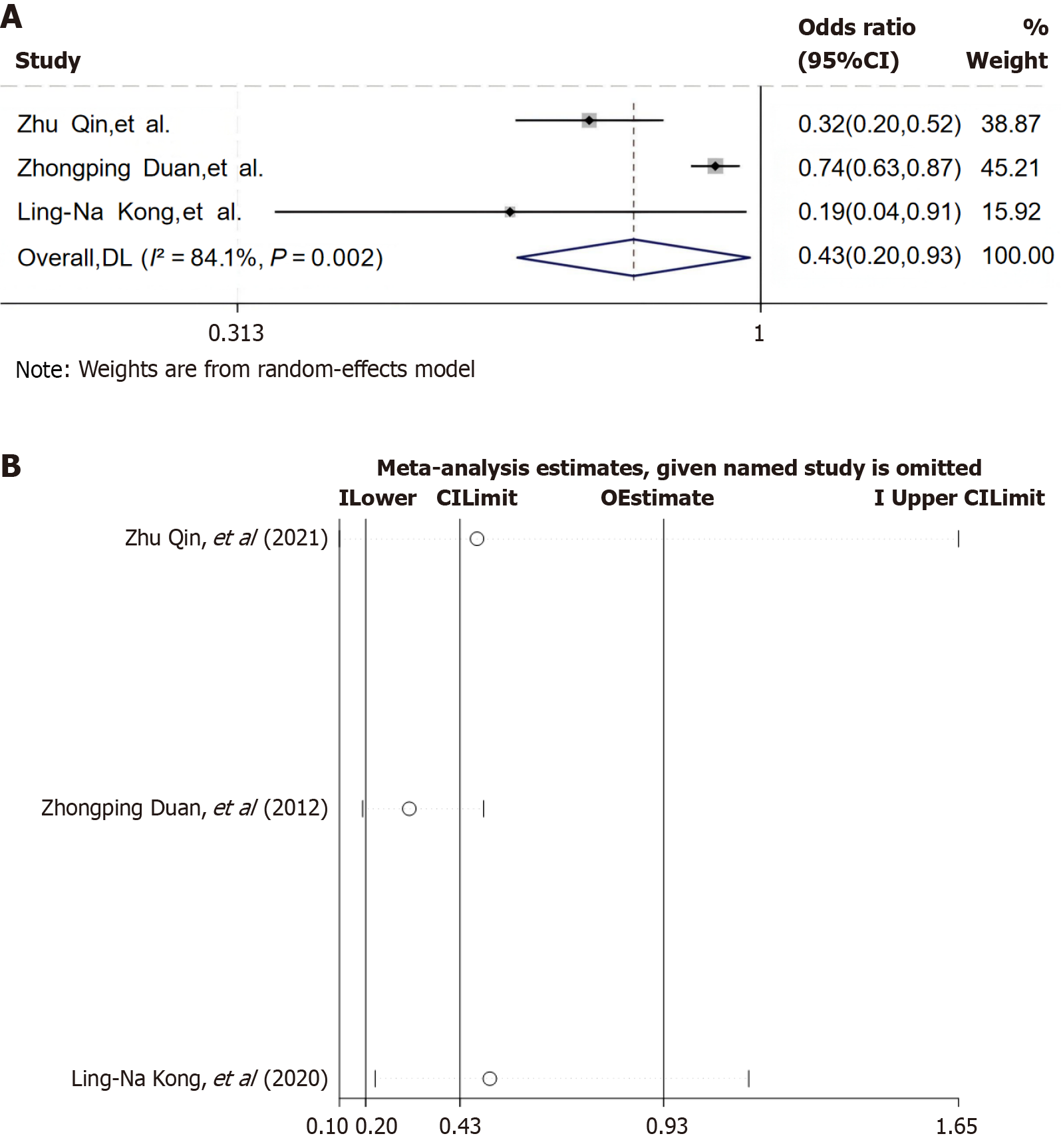

A total of four studies[6,12,15,16] concluded that education level was correlated with anxiety and depression in patients with CHB. The literature[6,15,16] mentioned high educational level as a protective factor, whereas one study[12] mentioned low educational level as a risk factor. In the combined literature[6,15,16], due to the significant heterogeneity observed between studies (I2 = 98.3%, P < 0.1), a random-effects model showed that high educational level was a protective factor for anxiety and depression in patients with CHB (OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.20-0.93, P < 0.05; Figure 6A). Sensitivity analysis using the random-effects model of educational level showed that the results were robust and not easily changed significantly due to changes in the number of studies (Figure 6B). The Egger’s test result was t = 1.95, P = 0.302 (> 0.05), and there was no risk of publication bias.

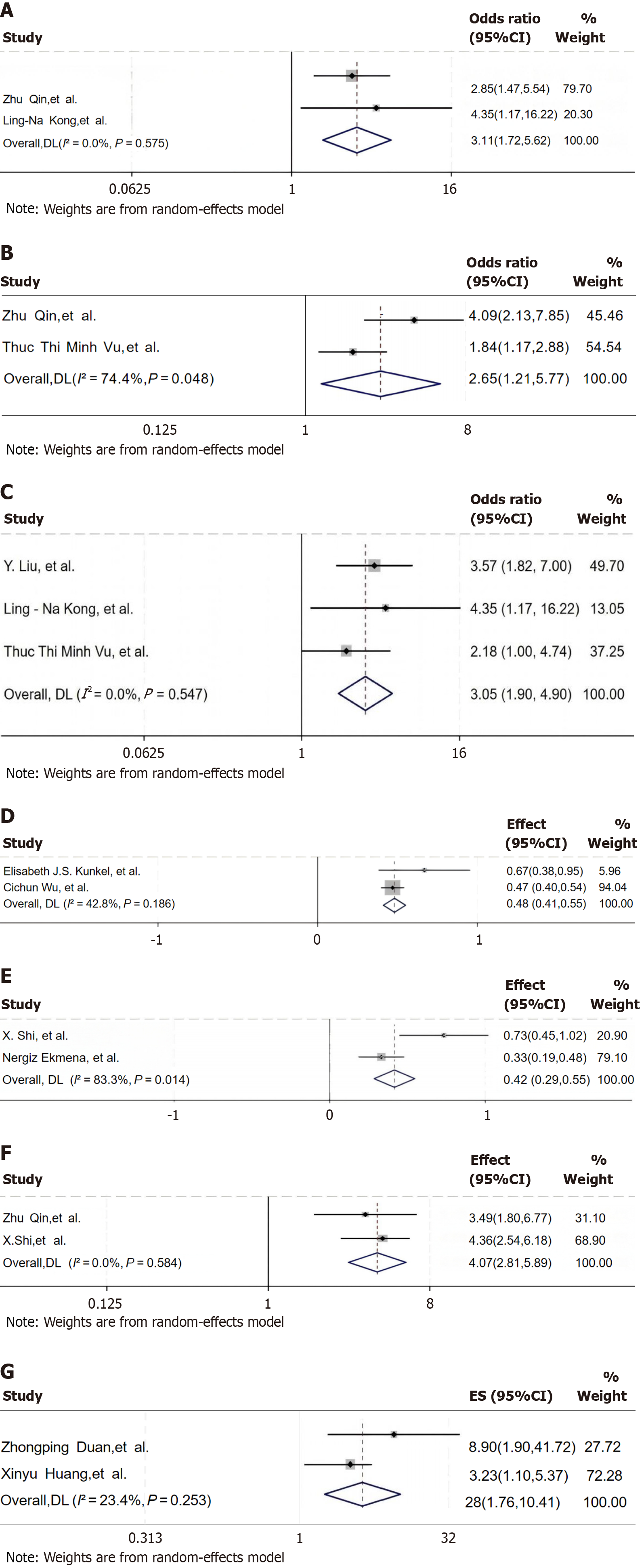

Two studies[6,16] evaluated the effect of treatment duration on negative emotions in patients with CHB. Since no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.1), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that patients with a longer treatment duration had a higher risk of developing depression and anxiety (OR = 3.11, 95%CI: 1.72-5.62, P > 0.05; Figure 7A).

Two studies[6,19] evaluated the effect of comorbidities on depression and anxiety in patients with CHB. Due to the significant heterogeneity observed among the studies (I2 = 74.4%, P < 0.1), a random-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher in patients with comorbidities than in patients without (OR = 2.65, 95%CI: 1.21-5.77, P < 0.05; Figure 7B).

Four studies[7,16,17,19] evaluated the effect of the age of patients with CHB on depression and anxiety. One of the studies[17] used Pearson correlation analysis (r = 0.610, P = 0.014), and three studies[7,16,19] used logistic regression analysis. These three studies[7,16,19] were combined. Since no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.1), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher with increasing patient age, (OR = 3.05, 95%CI: 1.90-4.90, P < 0.05; Figure 7C).

Three studies[10,13,15] evaluated the effect of sleep quality on depression and anxiety in the patients with CHB. One of the studies[15] used logistic regression analysis (OR = 2.99, 95%CI: 1.04-8.56), and two studies[10,13] used Pearson correlation analysis. The data of these 2 studies were combined after transformation using formulas (1) and (2). Since no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 42.8%, P > 0.1), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher in patients with poor sleep quality than in those with good sleep quality (Fisher’ Z = 0.48, 95%CI: 0.41-0.55, Summary r = 0.447, P < 0.05; Figure 7D).

Three studies[9,14,15] evaluated the effect of patients’ emotions on depression and anxiety in the patients with CHB. One of the studies[15] used logistic regression analysis (OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 1.03-1.19), and two studies[9,14] used Pearson correlation analysis. The data of these two studies were combined after transformation using formulas (1) and (2). Since significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 83.3%, P < 0.1), a random-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher in the patients with emotional instability than in those without (Fisher’s Z = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.29-0.55, Summary r = 0.393, P < 0.05; Figure 7E).

Two studies[6,9] evaluated the impact of the number of relapses in patients with CHB on depression and anxiety. Since no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 0.00%, P > 0.1), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results showed that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher in the patients with a higher number of relapses of hepatitis B than in those with a lower number (OR = 4.07, 95%CI: 2.81-5.89, P < 0.05; Figure 7F).

Two studies[9,15] evaluated the effect of the degree of hepatitis in patients on depression and anxiety in the patients with CHB. Since no significant heterogeneity was observed among the studies (I2 = 23.4%, P > 0.1), a fixed-effects model was used for analysis. The results indicated that the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety was higher in the patients with a higher degree of hepatitis than in those with a lower degree (OR = 4.28, 95%CI: 1.76-10.41, P < 0.05; Figure 7G).

After combining the data in this meta-analysis, the results showed that the probabilities of comorbid depression and anxiety in the patients with CHB were relatively high (30.1% and 40.2%). The pooled prevalence of comorbid depression was 30.1% (95%CI: 0.182-0.420, 11 studies) and of anxiety was 40.2% (95%CI: 0.126-0.678, 7 studies) in the patients with CHB, with overall negative emotions at 33.7%. The evidence strength was moderate, limited by significant heterogeneity (I2 > 98%), reflecting disparities in the diagnostic criteria across regions.

Evaluating the correlative factors of comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with CHB remains a significant challenge. Calculation of the combined effect sizes identified eight factors significantly associated with depression and anxiety.

Higher education acts as a protective factor (OR = 0.43) by enhancing health literacy and access to evidence-based information. Patients with CHB and a lower educational level generally have relatively weaker self-management abilities in various aspects, such as medication compliance, symptom monitoring, dietary adjustment, and social coping. These patients have insufficient awareness of the importance of disease management, are more likely to be afraid of hepatitis B, are reluctant to talk about their condition with others, and lack the relevant knowledge and skills to effectively implement self-management measures. Consequently, these patients are more prone to negative emotions, such as fear, anxiety, and depression. In contrast, patients with a higher educational level know how to obtain hepatitis B-related knowledge and coping methods through multiple channels.

Older age (≥ 40 years) and longer treatment duration were found to be robust risk factors (OR = 3.05, 95%CI: 1.90-4.90 and OR = 3.11, 95%CI: 1.72-5.62, respectively) in this study. Currently, no treatment method can completely eliminate HBV from the patient’s body[20]. Over time, patients often become frustrated about the incurable nature of the disease and frequently worry excessively about their prognosis. Besides the financial pressure of long-term treatment, patients are also concerned about disease progression and infectivity. This disease is protracted and recurrent, increasing the probability of hepatitis B-related complications. With the gradual aggravation of clinical symptoms and the decline in quality of life, most patients are under great psychological pressure and remain in a state of emotional instability[21-23].

Our study showed that poor sleep quality was significantly correlated with comorbid mental health issues (Fisher’s Z = 0.48, r = 0.447, P < 0.05), forming a bidirectional cycle with depression. A survey by Zheng et al[24] reported that patients with CHB often have problems with poor sleep quality, mainly caused by increased toxin levels in the body due to the disease, hormonal imbalance, and increased psychological burden. Huang et al[8] found that the prevalence of depression in patients with CHB was 29.2%, and the prevalence of insomnia was 46.4%. Insomnia was almost universal among depressed patients. Insomnia may be a manifestation of depression, and the two affect each other. The study also found that liver function impairment affects thyroid hormone metabolism, reducing the FT3 Level, which in turn aggravates depression and insomnia symptoms. Severe sleep disorders affect patient quality of life, disrupt normal rest and recovery, and affect patient emotions.

The analysis of this study revealed that the emotional stability of patients with CHB was also a key factor affecting their mental health. In this study, patients with CHB who were emotionally unstable had a higher risk of combined depression and anxiety (Fisher’s Z = 0.42, Summary r = 0.393, P < 0.05). Misunderstandings about the infectivity of HBV and social discrimination also increase the psychological pressure on patients with CHB, thus promoting the development of mental disorders or depression. A study by Li et al[25] in the Dalian area of China reported that approximately 85% of the participants expressed sympathy for HBV-infected individuals. However, a study in Vietnam reported that 4.8% of patients with CHB had experienced blame, 10.2% felt ashamed, and 48.5% felt discriminated against in medical institutions. Due to external influences, patients often experience uncontrolled emotions, which also reduces their immunity and aggravates the condition. Therefore, it is very important to eliminate the psychological barriers of patients with CHB.

Our study showed that repeated illness relapses and a high degree of hepatitis were key risk factors influencing depression and anxiety in patients with CHB. Frequent relapses (≥ 3 times/year) and severe hepatitis (Child-Pugh class C) showed the highest risk (OR = 4.07, 95%CI: 2.81-5.89 and OR = 4.28, 95%CI: 1.76-10.41, respectively). As patients become older and the duration of virus carriage lengthens, depressive feelings are more likely to occur. Experiencing multiple disease relapses increases patients’ anxiety, significantly elevates stress-related hormones, and decreases the body’s immune capacity. In turn, decreased immunity exacerbates the changes in the disease, creating a vicious cycle that worsens depressive emotions[26,27]. Considering the characteristics of hepatitis B itself, the severity of the disease is closely linked to the occurrence of depression and anxiety. Our meta-analysis results showed a 4.28-fold increase in the risk of comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with a high degree of hepatitis. A study by Zhu et al[28] found that patients with Child-Pugh class C had a higher risk of depression. In addition, a study by Mirabdolhagh et al[29] found that patients with CHB had more severe depressive symptoms than inactive HBV carriers. Since patients with a higher degree of hepatitis usually experience symptoms, such as ascites, jaundice, and hepatic encephalopathy, and are also uncertain about the disease and their future lives, all of which can trigger or exacerbate depressive and anxious emotions.

It also should be noted that two of the included studies in this review suggested that income level had a significant effect on depression and anxiety in patients with CHB. However, the evaluation results of a study[7] indicated that a low-income level was a risk factor (OR = 2.38, 95%CI: 1.34-4.25), whereas the evaluation result of literature[19] showed that a high-income level was a protective factor (OR = 0.32, 95%CI: 0.13-0.76), making it impossible to calculate the combined effect size. A study by Tu et al[30] concluded that patients with CHB may have difficulty paying the out-of-pocket expenses related to blood tests and imaging examinations required for disease-staging assessments. The continuous management of CHB and physical symptoms also may lead to income loss and exacerbate financial difficulties. Moreover, the healthcare of the affected individuals is not the only cost associated with a HBV diagnosis. Family members of patients with CHB undergoing testing, vaccination, or treatment can incur a greater financial burden. A study on the annual economic burden of HBV-related diseases in 12 cities in China found that the average annual intangible cost was 6611.10 USD, imposing a heavy financial burden and thus causing negative emotions in patients[31].

Therefore, in clinical practice, psychological support should be provided to early stage HBV-carrying patients. For patients with CHB with severe conditions, psychological state assessment and intervention are necessary. Timely counseling should be given to help patients cope with the psychological effect of the disease. In terms of health education, medical staff should provide targeted explanations of hepatitis B disease knowledge based on the educational level and comprehension ability of patients with CHB. This should cover aspects, such as the treatment process, transmission modes, and disease prognosis. Diverse forms, such as brochures, video demonstrations, and online communication platforms, can be used to enhance patients’ sense of cognitive control over the disease and treatment compliance, alleviating the fear and anxiety caused by a lack of knowledge. It is recommended that patients be guided to face the disease with a positive attitude, and when necessary, to adopt appropriate psychological therapies to deal with the psychological effect of the disease and regulate patients’ emotions. Patients’ family members should be encouraged to actively participate in the patients’ daily care and psychological support. Simultaneously, medical institutions can organize mutual-aid groups for patients with CHB to promote experience sharing and emotional communication among patients, reducing the sense of loneliness and helplessness caused by the disease and improving the patients’ psychological environment.

Several limitations at the study, outcome, and review levels merit discussion. At the study level, potential biases persisted despite the application of meta-analytic methods, including selection bias from cross-sectional designs in 11 of the 14 studies, which introduced recall bias in retrospective data collection, and performance bias due to only three studies (21%) using blinded mental-health assessments. Incomplete covariate adjustment for factors, such as antiviral therapy or comorbidities, further complicated interpretation of the results. At the outcome level, significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50% for key outcomes) arose from diverse diagnostic tools and regional sample variations (anxiety prevalence ranged from 2.1% in Turkey to 76.3% in Australia), compromising the stability of pooled-effect sizes. For example, treatment duration showed an OR of 3.11 (95%CI: 1.72-5.62, P < 0.05) in only two studies, limiting the statistical power. At the review level, publication bias probably occurred due to exclusion of non-English studies and gray literature, and reporting bias was evident in the inconsistent outcome reporting. The absence of a unified assessment tool for depression and anxiety in patients with CHB exacerbated heterogeneity, affecting the reliability of the results.

Future research should prioritize rigorously designed, multi-center, large-sample studies using standardized tools (e.g., PHQ-9/GAD-7) to reduce heterogeneity. Exploring unstudied factors, such as social-support networks and coping styles, and analyzing interactions between biological markers and psychosocial stressors, will deepen our understanding of comorbid mechanisms. Inclusive literature searches and advanced meta-analytical techniques can also mitigate biases and strengthen synthesis of evidence.

This meta-analysis identified eight factors associated with comorbid depression and anxiety in patients with CHB, including high educational attainment as a protective factor (OR = 0.43), older age (OR = 3.05), longer treatment duration (OR = 3.11), and severe hepatitis (OR = 4.28) as key risk factors. These findings are consistent with those of previous research, highlighting that patients with CHB have elevated economic and mental-health burdens due to disease chronicity and social stigma. The results provide a clinical foundation for prioritizing mental-health screening and tailored interventions for older patients with CHB and lower educational and income levels. Future studies should address methodological limitations to inform evidence-based guidelines, ultimately enhancing the mental health of patients with CHB and optimizing disease management.

| 1. | Burki T. WHO's 2024 global hepatitis report. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:e362-e363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Usuda D, Kaneoka Y, Ono R, Kato M, Sugawara Y, Shimizu R, Inami T, Nakajima E, Tsuge S, Sakurai R, Kawai K, Matsubara S, Tanaka R, Suzuki M, Shimozawa S, Hotchi Y, Osugi I, Katou R, Ito S, Mishima K, Kondo A, Mizuno K, Takami H, Komatsu T, Nomura T, Sugita M. Current perspectives of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2402-2417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Katcher JG, Klassen AC, Hann HW, Chang M, Juon HS. Racial discrimination, knowledge, and health outcomes: The mediating role of hepatitis B-related stigma among patients with chronic hepatitis B. J Viral Hepat. 2024;31:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Freeland C, Racho R, Kamischke M, Moraras K, Wang E, Cohen C, Kendrick S. Health-related quality of life for adults living with hepatitis B in the United States: a qualitative assessment. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5:121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Han B, Yuan Q, Shi Y, Wei L, Hou J, Shang J, Han Y, Jin C, Chan PL, Zhuang H, Li J, Cui F. The experience of discrimination of individuals living with chronic hepatitis B in four provinces of China. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0195455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Qin Z, Shen Y, Wu Y, Tang H, Zhang L. Analysis of risk factors for mental health problems of inpatients with chronic liver disease and nursing strategies: A single center descriptive study. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e2406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu Y, Tang K, Long J, Zhao C. The association between hepatitis B self-awareness and depression: Exploring the modifying effects of socio-economic factors. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:330-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang X, Zhang H, Qu C, Liu Y, Bian C, Xu Y. Depression and Insomnia Are Closely Associated with Thyroid Hormone Levels in Chronic Hepatitis B. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:2672-2678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shi XH, Xun J, Wang SP, Zhang J. [Depression and its risk factors in patients with chronic viral hepatitis B]. Zhognguo Gonggong Weisheng. 2010;26:693-694. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Kunkel EJ, Kim JS, Hann HW, Oyesanmi O, Menefee LA, Field HL, Lartey PL, Myers RE. Depression in Korean immigrants with hepatitis B and related liver diseases. Psychosomatics. 2000;41:472-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Weinstein AA, Kallman Price J, Stepanova M, Poms LW, Fang Y, Moon J, Nader F, Younossi ZM. Depression in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and chronic viral hepatitis B and C. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hajarizadeh B, Richmond J, Ngo N, Lucke J, Wallace J. Hepatitis B-Related Concerns and Anxieties Among People With Chronic Hepatitis B in Australia. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e35566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wu C, Xie J, Liu F. Incidence and factors influencing sleep disorders in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection: A case-control study. J Viral Hepat. 2023;30:607-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ekmen N, Can G, Can H. Preliminary examination of the relations between disease stage, illness perceptions, coping strategies, and psychological morbidity in chronic hepatitis B and C guided by the Common-Sense Model of Illness. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;33:932-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Duan Z, Kong Y, Zhang J, Guo H. Psychological comorbidities in Chinese patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2012;34:276-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kong LN, Yao Y, Li L, Zhao QH, Wang T, Li YL. Psychological distress and self-management behaviours among patients with chronic hepatitis B receiving oral antiviral therapy. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:266-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Keskin G, Gümüs AB, Orgun F. Quality of life, depression, and anxiety among hepatitis B patients. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2013;36:346-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu WJ, Zhang YH, Jiang HY. Relationship of anxiety state with lymphocyte subsets and the effect of Chinese medical treatment on anxiety in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Chin J Integr Med. 2011;17:302-306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vu TTM, Le TV, Dang AK, Nguyen LH, Nguyen BC, Tran BX, Latkin CA, Ho CSH, Ho RCM. Socioeconomic Vulnerability to Depressive Symptoms in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Agarwal R, Gupta E, Samal J, Rooge S, Gupta A. Newer Diagnostic Virological Markers for Hepatitis B Virus Infection. Euroasian J Hepatogastroenterol. 2024;14:214-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yan M, Ye H, Chen Y, Jin H, Zhong H, Pan B, Dai Y, Wu B. Economic burden of hepatitis B patients and its influencing factors in China: a systematic review. Health Econ Rev. 2024;14:99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Valizadeh L, Zamanzadeh V, Negarandeh R, Zamani F, Hamidia A, Zabihi A. Psychological Reactions among Patients with Chronic Hepatitis B: a Qualitative Study. J Caring Sci. 2016;5:57-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Abbott J, Aldhouse NVJ, Kitchen H, Pegram HC, Brown F, Macartney M, Villasis-Keever A, Sbarigia U, Ito T, Chan EKH, Kennedy PT. A conceptual model for chronic hepatitis B and content validity of the Hepatitis B Quality of Life (HBQOL) instrument. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2024;8:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng Y, Wang XW, Xia CX. Effects of different intervention methods on psychological flexibility, negative emotions and sleep quality in chronic hepatitis B. World J Psychiatry. 2023;13:753-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 25. | Li G, Wang G, Hsu FC, Xu J, Pei X, Zhao B, Shetty A. Effects of Depression, Anxiety, Stigma, and Disclosure on Health-Related Quality of Life among Chronic Hepatitis B Patients in Dalian, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:988-994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fu H, Jiang S, Song S, Zhang C, Xie Q. Causal associations between chronic viral hepatitis and psychiatric disorders: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1359080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lin Y, Wu B, Lin P, Zhang L, Li W. Nursing observations of stage-based care in patients diagnosed with hepatitis B virus infection based on TBIL and ALT levels. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e38072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhu HP, Gu YR, Zhang GL, Su YJ, Wang KE, Zheng YB, Gao ZL. Depression in patients with chronic hepatitis B and cirrhosis is closely associated with the severity of liver cirrhosis. Exp Ther Med. 2016;12:405-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mirabdolhagh Hazaveh M, Dormohammadi Toosi T, Nasiri Toosi M, Tavakoli A, Shahbazi F. Prevalence and severity of depression in chronic viral hepatitis in Iran. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2015;3:234-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tu T, Block JM, Wang S, Cohen C, Douglas MW. The Lived Experience of Chronic Hepatitis B: A Broader View of Its Impacts and Why We Need a Cure. Viruses. 2020;12:515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zhang S, Ma Q, Liang S, Xiao H, Zhuang G, Zou Y, Tan H, Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhang L, Feng X, Xue L, Hu D, Cui F, Liang X. Annual economic burden of hepatitis B virus-related diseases among hospitalized patients in twelve cities in China. J Viral Hepat. 2016;23:202-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/