Published online Oct 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.108491

Revised: June 18, 2025

Accepted: August 6, 2025

Published online: October 19, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 23.8 Hours

Intellectual disability (ID), affecting 1%-3% of children globally, presents significant challenges for parents that often translate into occupational stress. While studies document elevated parenting stress levels (33.57 vs 26.46 in controls), job-related impacts remain poorly understood. This study employs propensity score matching (PSM) to rigorously analyze work stress determinants among parents of preschool-aged children with ID, controlling for socioeconomic and behavioral confounders. The research bridges a critical gap by examining how workplace demands intersect with special caregiving responsibilities, aiming to identify modifiable risk factors for targeted interventions. Findings will inform evidence-based workplace accommodations and support policies, offering novel insights into the occupational consequences of parenting a child with ID through advanced causal inference methods. This work holds important implications for hazard ratio (HR) policies and social support systems serving this vulnerable population.

To explore the factors affecting the job stress of parents of preschool children with mental retardation (MR), based on the PSM.

One hundred and twenty-five children aged 3-6 years who were treated in our hospital from December 2022 to December 2024 were included in the ques

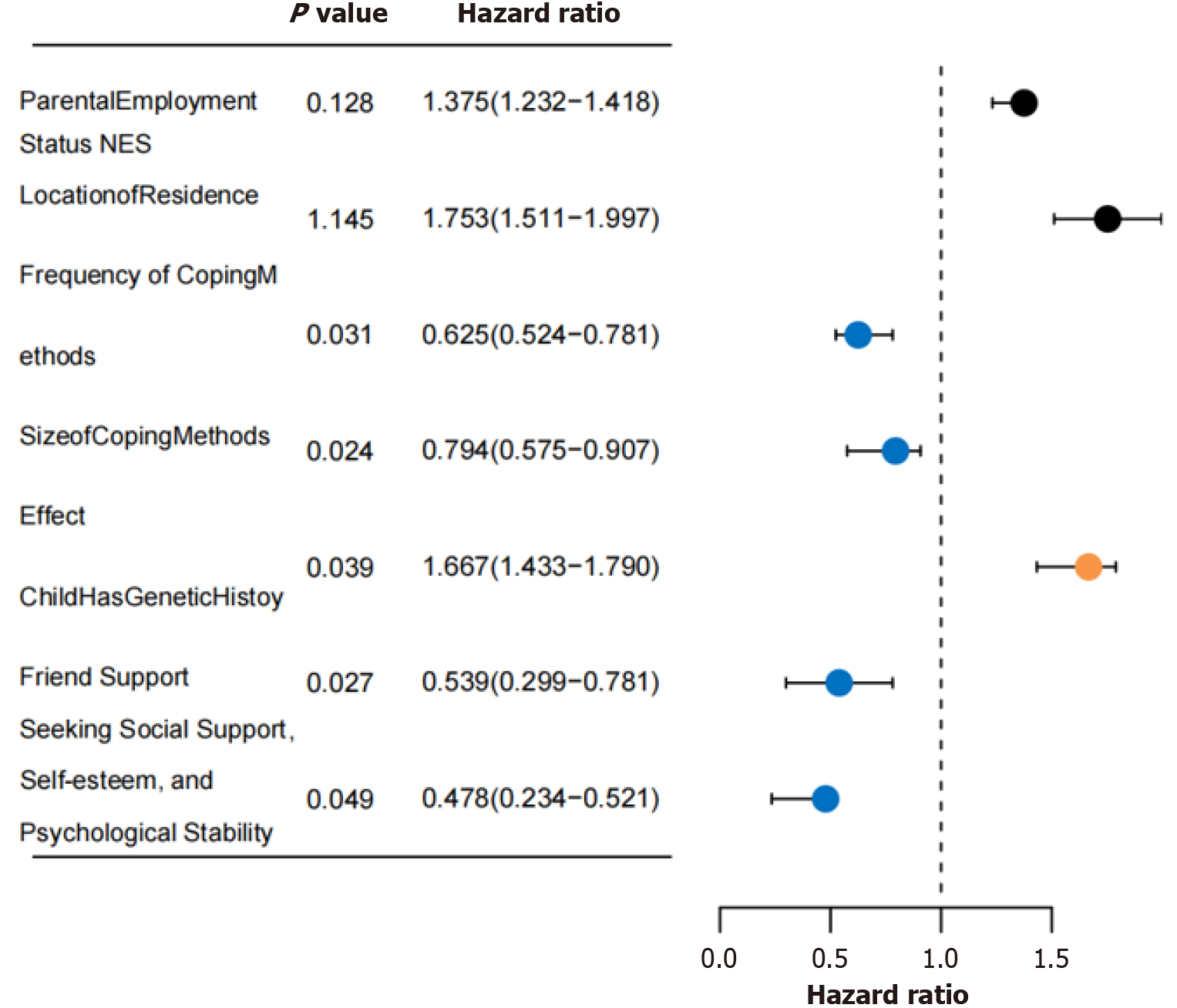

After matching, there were 97 cases in both groups. The differences of parents’ working status and family location in MR group were statistically significant, P < 0.05. Parents in MR group were significantly higher than those in control group in every dimension and total score, of which 75.22% were at a high level, P < 0.05. Univariate analysis shows that the older the parents are, the more unstable their work status is, the lower their education level is, the less their family income is, their location is in the countryside and the children have a genetic history, the higher their parental stress score is. Pearson correlation analysis showed that the total score of parental stress was related to supporting friends (r = -0.354), seeking social support, maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability (r = -0.146), coping style frequency (r = -0.476) and role size (r = -0.063). P < 0.05. Using the binary Logistic regression model, it was found that whether the child had a genetic history (HR = 1.667) was a risk factor affecting the parents’ job stress of MR children, and friends’ support (HR = 0.539), seeking social support (HR = 0.478) , maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability (HR = 0.625) , and the frequency and role of coping styles (HR = 0.794) were all its protective factors, P < 0.05.

Parents’ parental stress of most preschool children with MR is at a high level, in which children’s genetic history is its risk factor, and friends’ support, seeking social support, maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability, as well as the frequency and role of coping styles are its protective factors, which provides new intervention programs and measures to alleviate parents’ parental stress of MR children.

Core Tip: This study employs propensity score matching to explore key factors influencing parental job stress among caregivers of preschool children with mental retardation. By balancing covariates, the propensity score matching model identifies significant predictors, revealing that a child’s genetic history elevates stress, whereas supportive friendships, social support seeking, maintaining self-esteem, and effective coping strategies mitigate it. These findings emphasize the importance of targeted psychological interventions and family support policies to alleviate parental stress, thereby enhancing the quality of life for both mental retardation children and their families. This approach provides novel insights into managing caregiving pressures through empirical evidence.

- Citation: Li YJ, Fu ZW, Yu R, Duan JJ, Guo RQ, Li XY. Analysis of influencing factors of parents’ job stress of preschool children with mental retardation based on preference score matching. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(10): 108491

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i10/108491.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i10.108491

Mental retardation (MR), one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood, is characterized by intellectual disability (intelligence quotient < 70) and impaired social adaptive abilities, with a global prevalence of approximately 1.0%-3.0%[1]. Myers et al[2] found that parental stress, including the inability to cope with demands and the challenges of caring for children with developmental disabilities, is closely associated with higher levels of parenting stress, significantly impacting their emotional functioning, particularly among parents of children with developmental disorders. Ebadi et al[3] revealed that parents of children with intellectual disabilities had an average psychological stress score of 33.57, significantly higher than the 26.46 observed in parents of typically developing children (t = 3.87). Farajzadeh et al[4] demonstrated that parenting stress is strongly correlated with mental health status, especially for parents of children with special needs, where such stress significantly compromises their psychological well-being. Similarly, Grandjean et al[5] identified key sources of parental stress in raising children with special needs, including financial burdens, the child’s aggressive or challenging behaviors, and the uncertainty surrounding their developmental progress. These findings suggest that high levels of parenting stress not only harm parents’ physical and mental health but also hinder the rehabilitation process of affected children. Therefore, systematically analyzing the influencing factors of parenting stress among parents of MR children is crucial for developing targeted psychological interventions. Propensity score matching (PSM)[6], a quasi-experimental design method, reduces selection bias by balancing covariate distributions, thereby enhancing the reliability of causal inference. Although widely applied in fields such as education and political science[7], systematic analyses of parenting stress in parents of MR children remain scarce. To address this gap, this study moves beyond traditional cross-sectional research limitations by employing PSM to construct comparable study groups. It pioneers the development of a multidimensional influencing factor model for parenting stress among parents of preschool-aged MR children, providing empirical evidence for clinical psychological interventions and family support policies, ultimately improving the quality of life for MR children and their families.

General information: A stratified random sampling method was employed to select 125 children aged 3-6 years diagnosed with MR and receiving treatment at our hospital from December 2022 to December 2024. Their parents completed the questionnaire.

The diagnosis of MR was based on a comprehensive assessment of cognitive and social adaptive abilities, following established diagnostic criteria[8]. The diagnostic standards included: (1) Significantly below-average intellectual functioning for the child’s age, with notable cognitive impairment; (2) Insufficient social adaptive skills, including difficulties in independent living and fulfilling social roles, requiring long-term support for basic daily and social functioning; and (3) Onset of functional deficits before age 18. A confirmed diagnosis required meeting all three criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Children diagnosed with MR according to the diagnostic criteria[8]; (2) Age range of 3-6 years; (3) Parents serving as primary caregivers; (4) Parents fully informed about the study and providing signed consent; (5) Normal parental communication abilities; and (6) Parents possessing basic literacy.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Children with other severe acute or chronic comorbidities; (2) Parents with pre-existing significant psychological or psychiatric disorders prior to the child’s diagnosis; (3) Parents suffering from other conditions severely impairing daily functioning or overall health; (4) Parents cohabiting with the child for less than one year; and (5) Cases involving missing data, participant withdrawal, or parental noncompliance.

Sample size calculation: Based on the events-per-variable method[9], accounting for a 20% attrition rate and con

A cross-sectional survey design was employed. Hospital staff underwent standardized training to administer uniform questionnaires assessing general demographic characteristics and parental stress levels. Prior to data collection, trained personnel provided consistent instructions to all preschool children’s parents, explaining the study’s purpose to ensure cooperation and enhance response quality. Questionnaires were completed independently by parents.

The PSM model was applied using parental stress presence as the dependent variable, with demographic factors (child’s gender, age, residence location, payment method, and singleton status) as independent variables. A 1:1 matching ratio was implemented with a caliper value set at 0.01.

Baseline characteristics of preschool children and their parents: A self-designed questionnaire collected data on: Individual demographics (child’s age, gender, singleton status; parental age, gender, occupation, education level); Family environment (household type, income, medical payment method). The grouping of household income refers to the 2021 national per capita disposable income of 35128 yuan (average 2927.3 yuan/month) by the National Bureau of Statistics of China[10], with an integer of 3000 yuan/month.

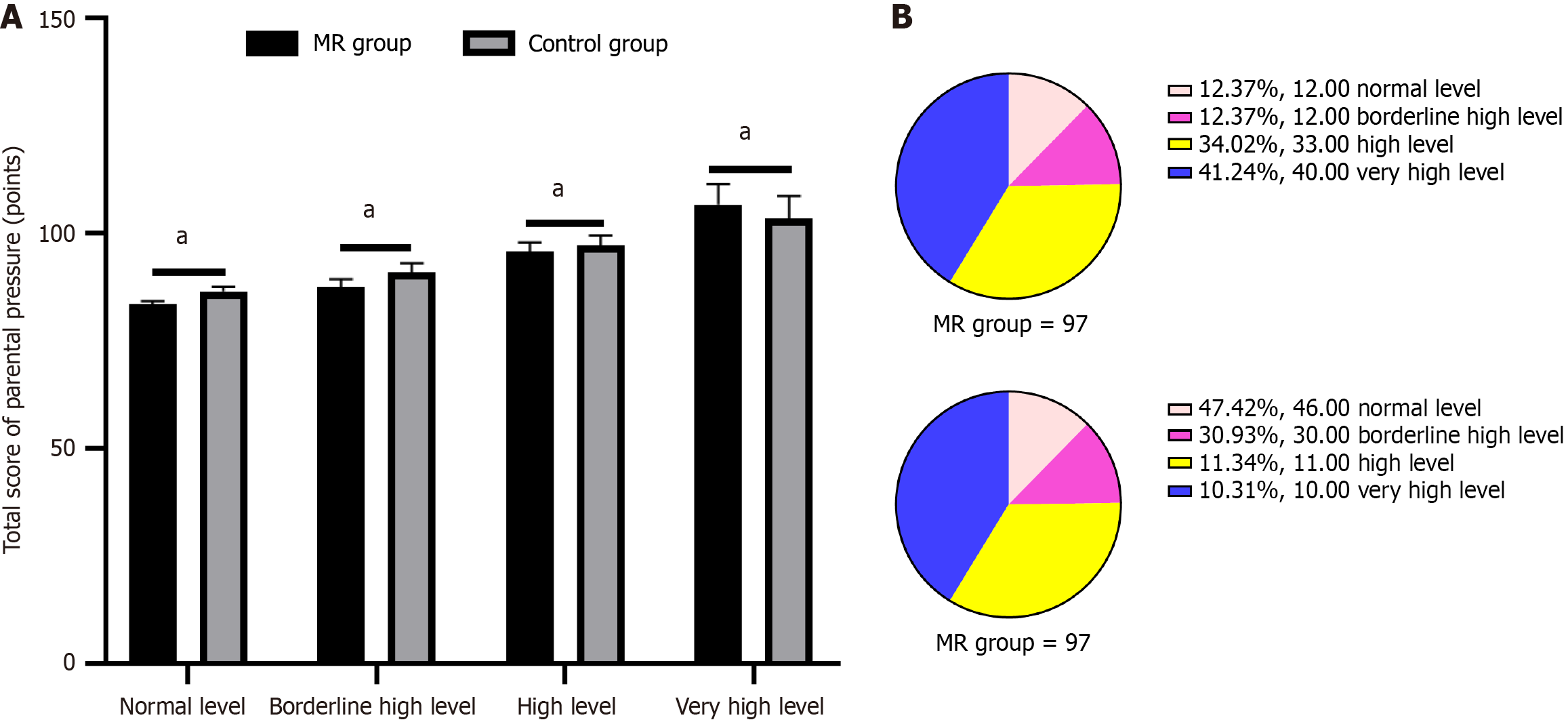

Investigation on parental occupational stress status: The Parental Stress Scale Short Form[11] was employed to assess parental stress levels, comprising three key dimensions: Parental distress (PD), parent-child dysfunctional interaction (P-CDI), and difficult child (DC). Each subscale consists of 12 items, totaling 36 entries scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree, 5: Strongly agree). Subscale scores range from 12 to 60 (sum of 12 items), while the cumulative total score spans 36-180. Scores ≤ 85 indicate normal stress levels, 86-90 reflect borderline-high stress, 90-99 signify high stress, and ≥ 99 denotes extreme stress. The scale demonstrates strong reliability, with an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.91 (subscale

Parent Coping Style Scale[12]: The Coping Health Inventory for Parents was used to evaluate coping strategies among parents of children with chronic illnesses, measuring three dimensions: Enhancing family cohesion and cooperation, maintaining a positive outlook, and seeking social support. Responses were recorded on a 4-point Likert scale (1: Never done, 4: Often done), with subscale scores ranging from 12 to 48 and a total score range of 36-144, where higher scores indicate more adaptive coping. The Chinese version demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.91 for the full scale (subscale α: 0.76-0.92) and a content validity index of 0.82. In this study, the overall Cronbach’s α reached 0.937.

Perceived Social Support Scale[13]: The Perceived Social Support (PSS) Scale assesses individuals’ PSS across three dimensions: Family support, friend support, and other support. Responses are scored on a 7-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree, 7: Strongly agree), with subscale scores ranging from 4 to 28 and a total score range of 12-84. Higher scores indicate greater PSS. The scale demonstrates excellent reliability, with an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.992. In this study, the total Cronbach’s α was 0.929.

Prior to the formal survey, a pilot study was conducted to refine the data collection forms for parental and child information and select optimal assessment tools. Official data collection commenced only after obtaining approval from the hospital department and head nurses to ensure compliance. Participating parents received detailed explanations of the study objectives and provided informed consent before completing the questionnaires. Researchers reviewed all submitted questionnaires, requesting parents to supplement any missing or incomplete responses. To ensure data accuracy, dual independent data entry was implemented, with discrepancies resolved by cross-referencing original questionnaires.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS 27.0 and Stata 16.0, with two-tailed tests applied. PSM employed a 1:1 matching ratio and a caliper of 0.02. Continuous variables were tested for normality; normally distributed data were presented as mean ± SD and compared using independent t-tests, while categorical data were expressed as, n (%) and analyzed via χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression identified factors influencing parental stress in preschoolers with MR. Pearson correlation assessed relationships between variables and parental stress. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

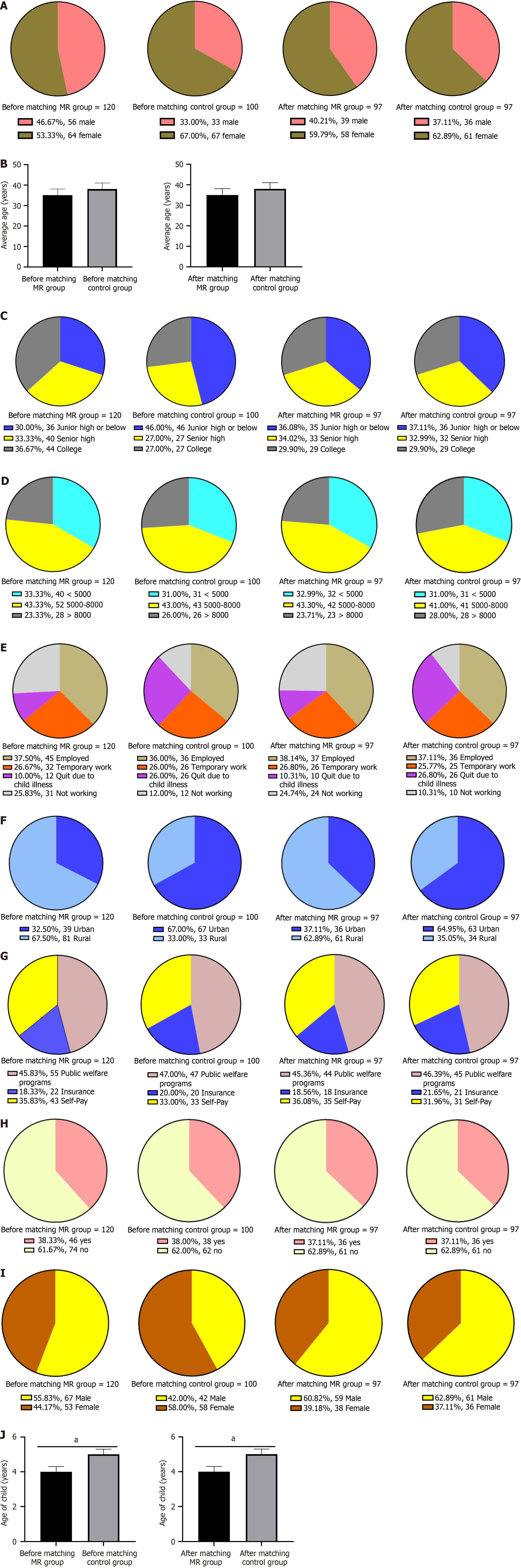

Among the initially enrolled 125 parents of child patients, 5 were excluded due to incomplete data, resulting in 120 participants completing the study. Before matching, significant differences (P < 0.05) were observed between the MR and control groups in parental sex, age, education level, as well as child sex and age. PSM was performed at a 1:1 ratio based on child sex/age and parental sex/age, family status, and education level. After matching, both groups comprised 97 participants each, with balanced baseline characteristics (P > 0.05). However, significant differences persisted in parental employment status and residential location (P < 0.05, Figure 1).

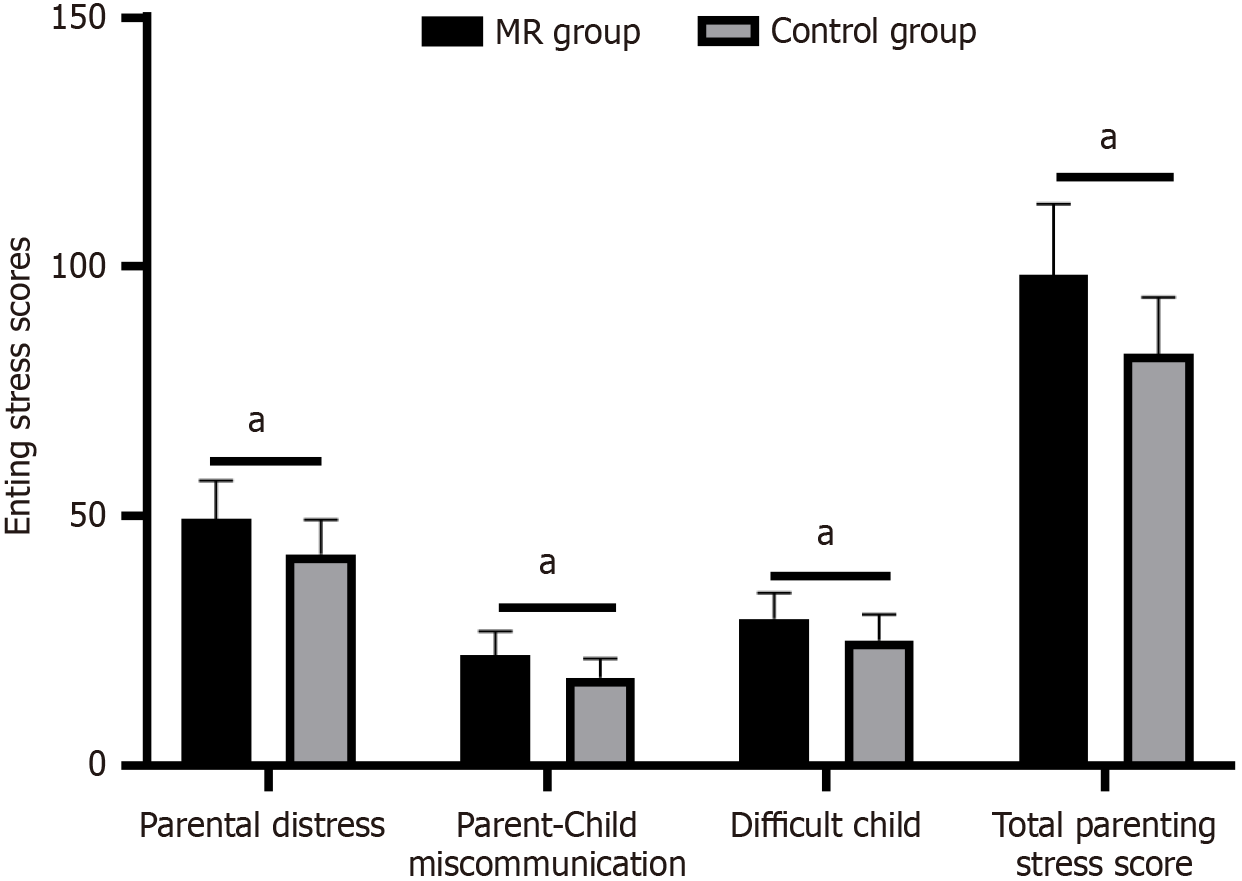

Post-matching analysis revealed significantly higher overall parenting stress levels in the MR group compared to controls [98.36 ± 14.15 vs (control value), P < 0.05]. Stress levels were elevated across all subscales, with the highest scores observed in PD and the lowest in P-CDI. Notably, 75.22% of MR parents scored > 90, indicating clinically significant stress levels (Figures 2 and 3).

Univariate analysis of parenting stress in preschool MR children’s parents showed significantly higher stress scores (P < 0.05) among older parents, those with unstable employment, lower education levels, reduced household income, rural residence, and parents of children with genetic history (Table 1).

| Variable | Number of cases, n (%) | Score for parental pressure (points), mean ± SD | F/t | P value | |

| Gender | Male | 39 (40.21) | 91.70 ± 16.09 | 0.549 | 0.585 |

| Female | 58 (59.79) | 89.80 ± 17.13 | |||

| Age | < 30 years old | 30 (30.93) | 91.72 ± 18.24 | 16.814 | 0.000 |

| 30-50 years old | 47 (48.45) | 89.27 ± 15.95 | |||

| > 50 years old | 20 (20.62) | 115.00 ± 18.06 | |||

| Parents’ work status | Employed | 37 (38.14) | 84.22 ± 13.81 | 4.2205 | 0.019 |

| Temporary work | 26 (26.80) | 95.60 ± 17.35 | |||

| Resignation due to child’s illness | 10 (10.31) | 93.00 ± 18.86 | |||

| Not working | 24 (24.74) | 93.00 ± 17.34 | |||

| Education level | Junior high school or below | 35 (36.08) | 92.82 ± 16.90 | 7.690 | 0.001 |

| High school | 33 (34.02) | 84.28 ± 15.31 | |||

| College degree or above | 29 (29.90) | 78.67 ± 10.00 | |||

| Family income | < 3000 yuan/month | 32 (32.99) | 92.19 ± 16.76 | 4.258 | 0.017 |

| 3000-6000 yuan/month | 42 (43.30) | 84.33 ± 15.20 | |||

| > 6000 yuan/month | 23 (23.71) | 80.67 ± 13.24 | |||

| Home location | City | 36 (37.11) | 86.79 ± 16.01 | 1.991 | 0.049 |

| Rural area | 61 (62.89) | 93.48 ± 15.98 | |||

| Does the patient have a genetic history | Have | 11 (11.34) | 108.83 ± 25.86 | 3.471 | 0.000 |

| Not have | 86 (88.66) | 89.59 ± 16.01 | |||

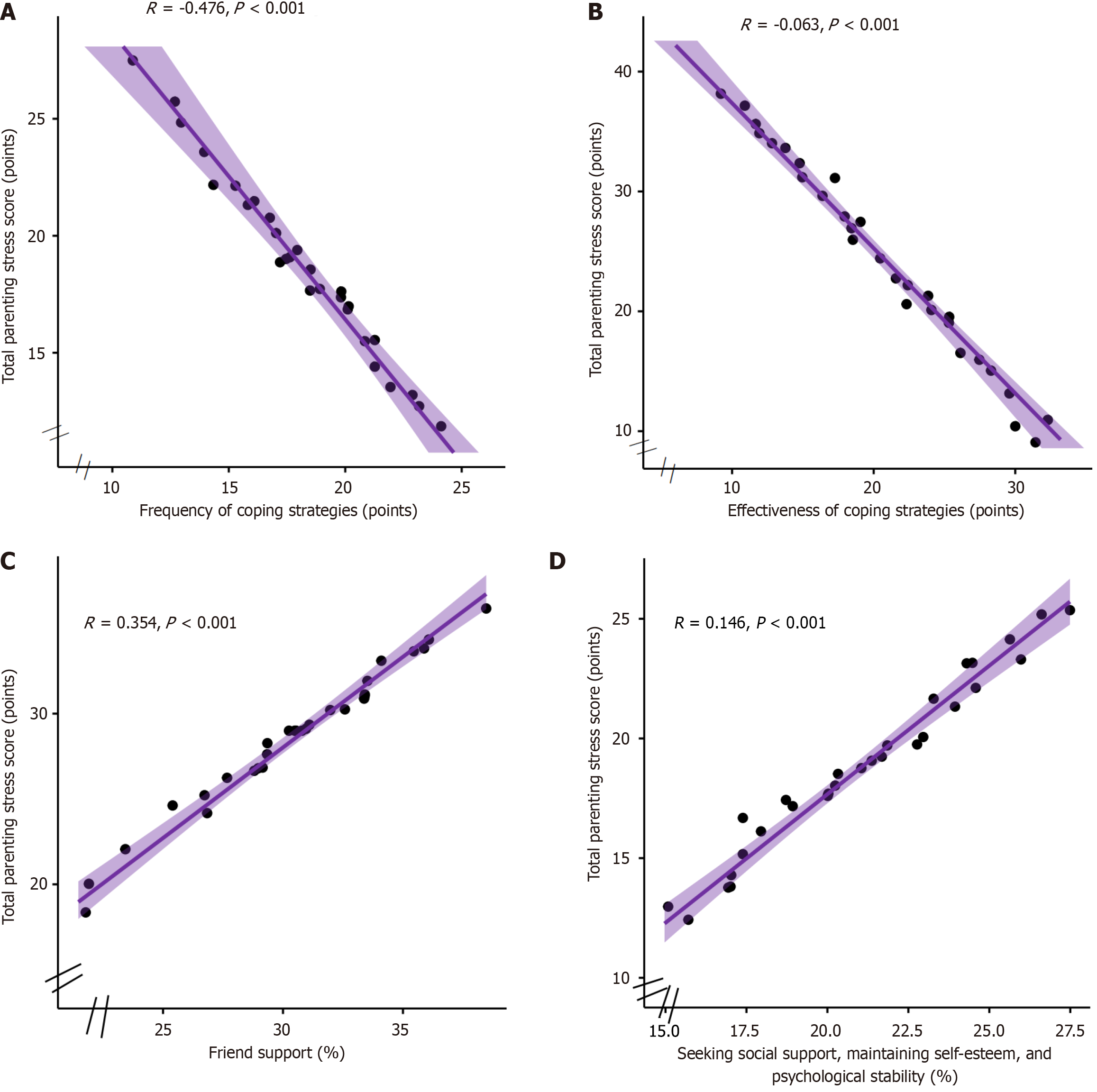

Pearson correlation analysis demonstrated significant positive associations between total parenting stress scores and PD, P-CDI, and DC subscales (all P < 0.05). Negative correlations were observed with friend support (r = -0.354), social support seeking and self-esteem maintenance (r = -0.146), coping frequency (r = -0.476), and coping efficacy (r = -0.063) (Figure 4).

Using total parenting stress scores as the dependent variable and statistically significant variables from univariate and correlation analyses as independent variables, binary logistic regression analysis, with variance inflation factor > 10 for multicollinearity screening, identified several significant predictors after controlling for confounders (parental age, education level, and family income): Genetic history emerged as a risk factor [hazard ratio (HR) = 1.667, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.433-1.790], while protective factors included friend support (HR = 0.539, 95%CI: 0.299-0.781), social support seeking/self-esteem maintenance (HR = 0.478, 95%CI: 0.234-0.521), coping frequency (HR = 0.625, 95%CI: 0.524-0.781), and coping efficacy (HR = 0.794, 95%CI: 0.575-0.907), all with P < 0.05 (Figure 5).

MR is a prevalent disability requiring constant parental supervision, representing a significant negative life event that demands substantial physical, emotional, and temporal resources from families[14]. The prolonged rehabilitation process imposes heavy financial and psychological burdens[15], making urgent intervention necessary to enhance parental mental health and stress management skills. Research indicates that positive parental attitudes in developmental disorders actively promote child rehabilitation through improved caregiving[16].

Our propensity score-matched (1:1) analysis revealed significant differences in employment status and residential location between groups. Preschool MR children require intensive rehabilitation (2-3 weekly sessions of speech/sensory therapies with full parental accompaniment)[17], forcing caregivers to sacrifice work stability through frequent leave-taking, ultimately reducing income and career prospects. Most families struggle to access limited/expensive special education resources, relying instead on kinship care that further restricts work hours[18]. In under served areas, diagnostic/therapeutic delays beyond the critical 3-6 years window perpetuate lifelong disabilities, compounding care burdens[19]. These preschool-specific challenges create dual pressures - intensive developmental intervention while balancing career compromises - generating synergistic economic-psychological distress. MR parents demonstrated significantly higher stress scores across all dimensions vs controls, with most reaching clinically severe levels, confirming exceptional parenting challenges. However, although the initial sample size (n = 125) met the calculation requirements of the events-per-variable method, the sample size decreased to 97 pairs after PSM matching, which may affect the statistical validity. Future research needs to expand the sample size to enhance the robustness of the results.

Our study identified significantly elevated parenting stress in both younger (< 30 years) and older (> 50 years) caregivers of preschool MR children. Younger caregivers’ limited childcare experience and insufficient knowledge about MR-specific interventions often lead to ineffective approaches (over correction, unrealistic expectations, or inadequate interaction)[20], slowing child progress and increasing anxiety. Older caregivers face physical exhaustion from intensive rehabilitation demands[21] and heightened anxiety about their child’s future independence, particularly regarding long-term care after their own aging. Additional stress factors included parental education, employment status, residential location, income, and child’s genetic history. Highly educated parents better understood MR treatment guidelines and developmental milestones, enabling timely intervention adjustments, while limited education often resulted in delayed diagnosis and ineffective alternative treatments[22]. Rural families lacking access to inclusive preschools or daycare centers struggled with unguided home care, compromising early development. Low-income households’ inability to afford essential therapies (speech/sensory integration) forced reliance on limited community resources, accumulating developmental delays and chronic stress[23]. These interrelated factors collectively exacerbate parenting stress in MR families.

Our study demonstrated significant negative correlations between total parenting stress and both PSS and parental coping strategies, consistent with Fu et al’s findings[24] (r = -0.30 for stress-support; r = 0.22 for parenting efficacy-support). A systematic review further confirmed that active coping techniques correlate with reduced parental stress[25]. Therefore, parents are encouraged to participate in supportive social activities such as family gatherings and support groups at least once a week, or establish a “MR Family Mutual Aid Network” in the community, and provide regular psychological counseling and parenting experience sharing to alleviate parents’ sense of isolation; At the same time, 2-3 times a week, parents are guided through cognitive-behavioral therapy to master problem-solving strategies, and a stress management manual is provided, covering emotional regulation and parent-child interaction skills such as mindfulness exercises, in order to reduce parental stress. Further multivariate analysis in this study revealed that the child’s genetic history, support from friends, seeking social support, maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability, as well as the frequency and magnitude of coping strategies were all influencing factors. The reason for this may be that genetic history is associated with specific syndromes such as Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome as a risk factor, and the increased medical burden caused by comorbidities in children with Down syndrome can affect their parents’ stress levels. At the same time, parents may feel guilty or self blame for genetic diseases, especially during the critical period of language, cognitive, and social development before school age. Parents’ long-term anxiety due to concerns about the child’s future directly affects their mental health and caregiving ability[26], seeking support from friends and society can provide parents with practical parenting guidance and experience sharing, helping them master adaptive parenting strategies. It can also share parenting responsibilities by providing temporary childcare when necessary, further reducing the actual burden on parents. Empathy and listening can also enhance parents’ self-efficacy, thereby enhancing the family’s ability to cope with challenges and effectively alleviating parents’ loneliness and anxiety caused by long-term care pressure[27], research shows that effective coping strategies not only include external support, but also rely on parents’ own cognitive adjustment and behavioral practice[28]. Faced with the special needs of preschool MR children, parents need to adopt diverse coping strategies to maintain family balance and their own mental health. This study suggests that parents can alleviate parental stress by seeking social support, maintaining self-esteem and psychological stability. Therefore, medical staff should actively help parents of sick children adjust their mentality, provide effective medical information, encourage parents of sick children to establish good social relationships with those around them, and thereby reduce their parental pressure. However, this study is a cross-sectional design, and the results only reflect the correlation between variables, which cannot establish causal relationships. In the future, longitudinal studies will be needed to verify the time series effects of influencing factors; Moreover, PSM has not fully controlled for heterogeneity in family structure and social support networks, which may result in residual confounding bias.

In summary, this study revealed that most parents of preschool children with MR experience high levels of parenting stress. Key findings identified genetic history as a risk factor, while friend support, social support seeking, self-esteem maintenance, and both the frequency and effectiveness of coping strategies served as protective factors. These results provide valuable insights for developing targeted interventions to alleviate parenting stress in this population. However, the singularity of the sample source in this study limits the extrapolation of results, especially the needs of low-income or rural households have not been fully reflected. In the future, multi center cooperation (such as urban and rural hospitals, community service centers) is needed to improve sample representativeness.

| 1. | GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 3422] [Article Influence: 855.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Myers S, Collins B, Maguire S. Care coordination for children with a disability or developmental difficulty: Empowers families and reduces the burden on staff supporting them. Child Care Health Dev. 2024;50:e13158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ebadi M, Samadi SA, Mardani-Hamooleh M, Seyedfatemi N. Living under psychosocial pressure: Perception of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2021;34:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Farajzadeh A, Dehghanizadeh M, Maroufizadeh S, Amini M, Shamili A. Predictors of mental health among parents of children with cerebral palsy during the COVID-19 pandemic in Iran: A web-based cross-sectional study. Res Dev Disabil. 2021;112:103890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Grandjean C, Ullmann P, Marston M, Maitre MC, Perez MH, Ramelet AS; OCToPuS Consortium. Sources of Stress, Family Functioning, and Needs of Families With a Chronic Critically Ill Child: A Qualitative Study. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:740598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liang J, Hu Z, Zhan C, Wang Q. Using Propensity Score Matching to Balance the Baseline Characteristics. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:e45-e46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beaulieu-Jones BR, de Geus SWL, Rasic G, Woods AP, Papageorge MV, Sachs TE. A propensity score matching analysis: Impact of senior resident versus fellow participation on outcomes of complex surgical oncology. Surg Oncol. 2023;48:101925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Salvador-Carulla L, Bertelli M. 'Mental retardation' or 'intellectual disability': time for a conceptual change. Psychopathology. 2008;41:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Christodoulou E, van Smeden M, Edlinger M, Timmerman D, Wanitschek M, Steyerberg EW, Van Calster B. Adaptive sample size determination for the development of clinical prediction models. Diagn Progn Res. 2021;5:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liao X, Chai L, Liang Y. Income impacts on household consumption's grey water footprint in China. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755:142584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Luo J, Wang MC, Gao Y, Zeng H, Yang W, Chen W, Zhao S, Qi S. Refining the Parenting Stress Index-Short Form (PSI-SF) in Chinese Parents. Assessment. 2021;28:551-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Toledano-Toledano F, Moral de la Rubia J, McCubbin LD, Cauley B, Luna D. Brief version of the coping health inventory for parents (CHIP) among family caregivers of children with chronic diseases. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55:610-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 1238] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chen SQ, Chen SD, Li XK, Ren J. Mental Health of Parents of Special Needs Children in China during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rydzewska E, Dunn K, Cooper SA, Kinnear D. Mental ill-health in mothers of people with intellectual disabilities compared with mothers of typically developing people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65:501-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Herrera E, Baena S, Hidalgo V, Trigo E. The relationship between family quality of life, mindful attention, and social support in families of people with autism spectrum disorder. Int J Dev Disabil. 2024;70:604-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fucà E, Costanzo F, Ursumando L, Vicari S. Parenting Stress in Mothers of Children and Adolescents with Down Syndrome. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lindblad I, Landgren V, Gillberg C, Fernell E. Children born to parents with mild intellectual disability: Register-based follow-up of psychiatric and neurodevelopmental diagnoses and out-of-home placements. Acta Paediatr. 2024;113:1637-1643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sapiets SJ, Totsika V, Hastings RP. Factors influencing access to early intervention for families of children with developmental disabilities: A narrative review. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2021;34:695-711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Staunton E, Kehoe C, Sharkey L. Families under pressure: stress and quality of life in parents of children with an intellectual disability. Ir J Psychol Med. 2023;40:192-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | McCausland D, Brennan D, McCallion P, McCarron M. Balancing personal wishes and caring capacity in future planning for adults with an intellectual disability living with family carers. J Intellect Disabil. 2019;23:413-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kütük MÖ, Tufan AE, Kılıçaslan F, Güler G, Çelik F, Altıntaş E, Gökçen C, Karadağ M, Yektaş Ç, Mutluer T, Kandemir H, Büber A, Topal Z, Acikbas U, Giray A, Kütük Ö. High Depression Symptoms and Burnout Levels Among Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Multi-Center, Cross-Sectional, Case-Control Study. J Autism Dev Disord. 2021;51:4086-4099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Day JJ, Hodges J, Mazzucchelli TG, Sofronoff K, Sanders MR, Einfeld S, Tonge B, Gray KM; MHYPeDD Project Team. Coercive parenting: modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors in parents of children with developmental disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2021;65:306-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fu W, Li R, Zhang Y, Huang K. Parenting Stress and Parenting Efficacy of Parents Having Children with Disabilities in China: The Role of Social Support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cheng AWY, Lai CYY. Parental stress in families of children with special educational needs: a systematic review. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1198302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Marcinechová D, Záhorcová L, Lohazerová K. Self-forgiveness, Guilt, Shame, and Parental Stress among Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Curr Psychol. 2023;1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Park GA, Lee ON. The Moderating Effect of Social Support on Parental Stress and Depression in Mothers of Children with Disabilities. Occup Ther Int. 2022;2022:5162954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wen X, Ren J, Li X, Li J, Chen S. Parents' personality, parenting stress, and problem behaviors of children with special needs in China before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Psychol. 2022;1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |