Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.109671

Revised: June 19, 2025

Accepted: July 15, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 167 Days and 4.1 Hours

Childhood nephrotic syndrome (NS) outcomes vary widely based on steroid responsiveness and complications.

To evaluate steroid response, outcomes, and the use of steroid-sparing medica

This retrospective study evaluated the demographics and outcomes of 122 children aged 1–18 years with NS between 2011 and 2021 across three centers in Jordan. The outcomes assessed included steroid sensitivity rates, dependence, frequent relapses, complications [chronic kidney disease (CKD), end-stage kidney disease (ESKD)], infections, and need for steroid-sparing treatment.

Of 64% were boys; median age of disease onset was 4 years. Steroid-sensitive and steroid-resistant NS (SRNS) were observed in 81.1% and 18.9% of patients, res

Most patients were steroid sensitive, with minimal change being the most common. Focal segmental glomerulosclerosis was the predominant histopathology in the steroid-resistant cases. SRNS patients had worse outcomes, with more infections, CKD, and ESKD.

Core Tip: This retrospective study highlights the outcomes of nephrotic syndrome in Jordanian children, demonstrating that steroid resistant and frequent relapser have higher complication rates. It also emphasizes the importance of early identification and follow-up.

- Citation: Ajarmeh SA, Akl K, Al Shawabkeh M, Al Baramki J. Steroid response and outcomes in childhood nephrotic syndrome: A multicenter, cross-sectional study from Jordan. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(4): 109671

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i4/109671.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.109671

Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (NS) is a condition affecting 2-7 individuals per 100000 annually[1,2]. It is characterized by low albumin levels, hyperlipidemia, and generalized swelling. Diagnosis is confirmed if proteinuria exceeds 50 mg/kg/day, 40 mg/m2/hour, or a urine protein/creatinine ratio of > 2 mg/mg. Approximately 90% and 10% of patients have idiopathic nephrotic syndrome (INS) and secondary NS, respectively. Secondary NS is associated with infections, systemic diseases, malignancies, and other glomerular diseases. Minimal change disease (MCD) constitutes 85% of INS cases, with a steroid response rate exceeding 95%[3].

The treatment is based on results from several studies[4-8]. Prednisolone (PDN) is the first-line treatment for initial presentation and subsequent relapses[4], with the patient’s response to PDN being the most important predictor of prognosis and outcome[5,6]. Other factors influencing patient outcomes include the treatment duration, age at onset, and timing of first relapse[9,10]. Patients are classified as steroid-sensitive NS (SSNS) or steroid-resistant NS (SRNS) based on their response to PDN treatment. Most patients have SSNS, whereas 10%–20% have SRNS[5]. Of the patients with SSNS, 60%–80% will experience relapse. Among them, 50%–70% will have frequently relapsing NS (FRNS) if they relapse ≥ 2 times in 6 months or ≥ 4 times within 1 year. Patients are classified as having steroid-dependent NS (SDNS) if they experienced relapse before PDN discontinuation. The remaining 30%–50% of patients will have infrequent relapsing NS[9,11]. While most patients will ultimately achieve permanent remission, 10%–30% will carry the disease into adulthood[3,5].

Many immunosuppressive agents other than steroids are used to maintain remission in patients with steroid-related complications. The most frequently used agents include cyclosporine (CsA), tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), cyclophosphamide, levamisole, and rituximab[7-10]. Although the current treatment is guided by the most recent recommendations of the Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)[4] and the International Pediatrics Nephrology Association (IPNA)[7], many other pediatric nephrology societies have their own guidelines, leading to some variability in managing children with NS among pediatric nephrologists[9].

Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the steroid response, treatment, steroid-sparing medication choices, and outcomes in children with NS. We retrospectively collected and analyzed data from children with NS at three centers in Jordan. The data included demographics; NS type; management protocols; prednisolone dose used; and outcomes, mainly end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), dialysis modalities, transplantation, death, and occurrence of different complications of NS. SSNS, FRNS, SRNS, remission, and relapse were defined according to the guidelines of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children (ISKDC) and the IPNA[4,7].

This is a multicenter, retrospective, observational, cross-sectional study. Data from 122 patients were analyzed. Data were collected from three sites providing pediatric nephrology services in Jordan between 2011 and 2021. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the sample size could not be calculated a priori. Patients aged 1–18 years diagnosed with INS were included in the study. Patients with secondary NS were excluded. The participating centers were Karak Governmental Hospital (a teaching hospital affiliated with the University of Mutah) in Karak, southern Jordan; Al Bashir Governmental Hospital; and Jordan University Hospital in Amman; all of which are tertiary centers. All clinical data were retrospectively collected from the patients’ electronic health medical records system (HAKEEM). Patient variables including age, sex, age at first presentation, whether the patient underwent a kidney biopsy or genetic testing, and the rationale for these procedures, were recorded. Other data regarding patient follow up in outpatient nephrology clinics were collected. If the patient was in remission or relapse, the steroid dose received, steroid-sparing medication type, and any new complications were collected retrospectively from the medical records. The follow-up duration was recorded from initial diagnosis to the most recent clinic visit. The nephrologist’s PDN dose used (mg/kg or mg/m2), treatment duration of the first presentation, whether low-dose steroids were administered to prevent an upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) relapse, and steroid-sparing agent type. Responses to steroids (SRNS vs steroid-dependent or frequent relapse), the timing of the first relapse, and the number of relapses/year were recorded. Other outcomes, including steroid side effects or other NS complications, like thrombosis, peritonitis, and acute kidney injury (AKI), were also recorded. The number of patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) requiring dialysis or transplantation were recorded.

According to most recent IPNA guidelines[7], complete remission requires a urine protein creatine ratio sample ≤ 0.2 mg/mg or a negative or trace dipstick for 3 consecutive days. SSNS is achieving remission within 4 weeks of starting a standard prednisolone dose. Relapse requires a urine dipstick ≥ 3 + on 3 consecutive days, with or without reappearance of edema. SRNS is defined as failing to achieve remission within 4 weeks of treatment ± three methylprednisolone pulses. FRNS requires ≥ 2 relapses in the first 6 months following remission or ≥ 3 relapses in any 12 months. SDNS refers to a patient who relapses while receiving prednisolone therapy or relapses within 14 days of discontinuation.

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The student’s t-test was used for quantitative variables such as age, relapse frequency, and duration of follow up and presented as the mean ± SD, median and range, or percentage. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for qualitative variables, such as sex, disease type, and complications. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of Mutah University (reference number: 292022) and all other participating centers.

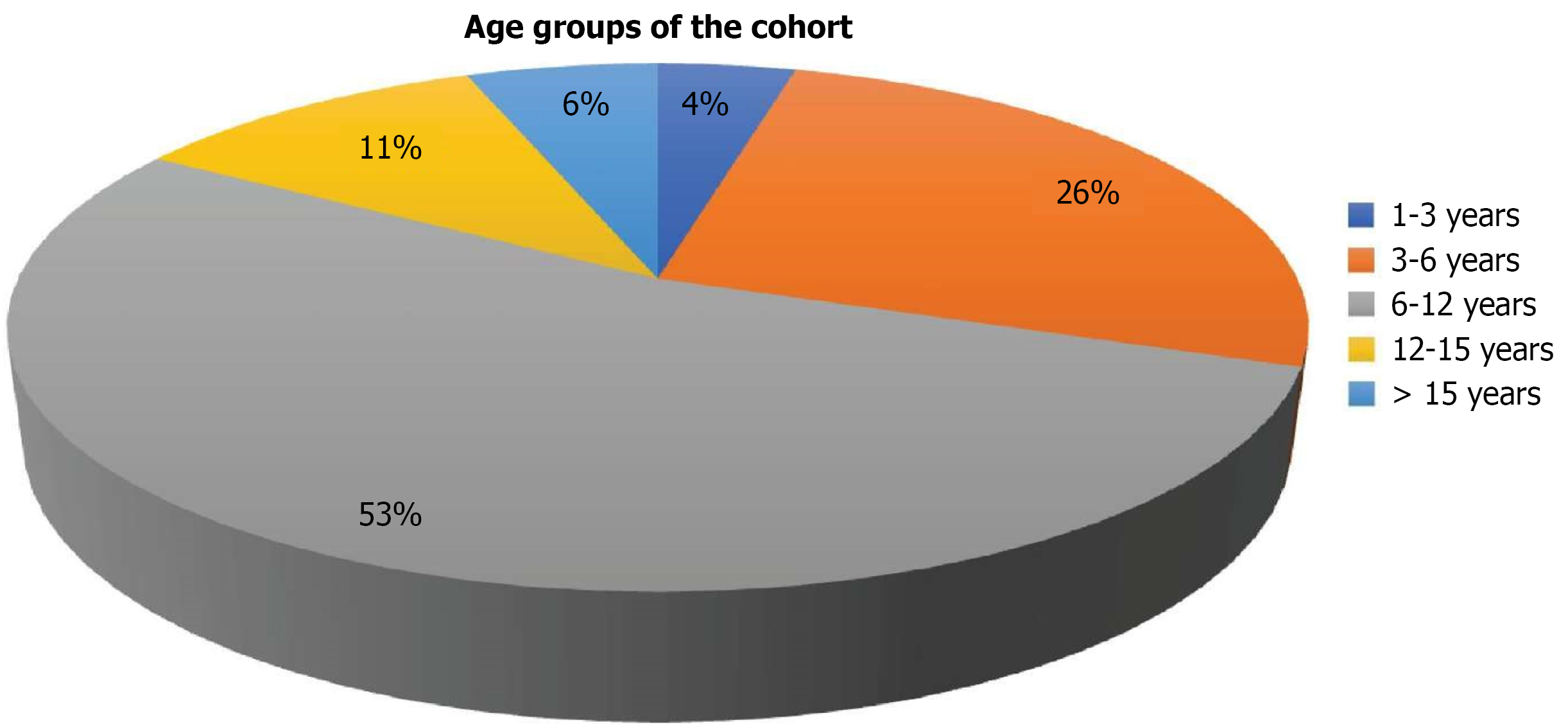

A total of 122 patients aged < 18 years diagnosed with INS were included in this study. Seventy eight (63.9%) were males, and no change was found in male predominance across the age groups. Table 1 presents the patient demographics. The median age of the cohort was 8 (range, 2–18) years, and the majority of the patients 65 (53.2%) were in the 6–12-year age group.

| Characteristic | Frequency (n = 122) | Percentage (%) |

| Male | 78 | 63.9 |

| Female | 44 | 36.1 |

| Center | ||

| Karak | 44 | 36.1 |

| Al Basheer | 62 | 50.8 |

| Jordan University | 16 | 13.1 |

| Positive family history | 19 | 15.6 |

| Underwent biopsy | 57 | 46.7 |

| Underwent genetic testing | 6 | 4.9 |

| Age at diagnosis, years (median) | 4 (1–14) | |

| Follow-up time, years (median) | 2 (1–15) | |

| Time to first relapse, months (median) | 9 (2–18) | |

| Median number of relapses per year median) | 2.6 ± 1.7 | |

| Median time of steroid-sparing use (years) | 2 (1–4) | |

| Median age of the cohort at data entry (years) | 8 (2–18) | |

| Premature | 4 | 3.3 |

| Birth weight < 2.5 kg | 10 | 8.2 |

| Clinical course and outcomes | ||

| Type of nephrotic syndrome | ||

| SSNS | 53 | 43.4 |

| SRNS | 23 | 18.9 |

| SDNS | 35 | 28.7 |

| FRNS | 11 | 9.0 |

| Use of steroid-sparing medications | 51 | 41.8 |

| Microscopic hematuria | 36 | 29.5 |

| Hypertension | 22 | 18.0 |

| Nephrotic syndrome complications | 49 | 40.2 |

| CKD and ESKD | 9 | 7.4 |

| Dialysis | 8 | 6.6 |

| Transplant | 4 | 3.3 |

| Death | 4 | 3.3 |

| Significant steroid side effects | 21 | 17.2 |

| Type of steroid side effects (n = 21) | ||

| Bone and leg pain | 7 | 33.3 |

| Aggression | 7 | 33.3 |

| Hypertension | 1 | 4.8 |

| Obesity | 6 | 28.6 |

The median follow-up time and age at diagnosis were 2 (range, 1-15) and 4 (range, 1–14) years, respectively (Figure 1).

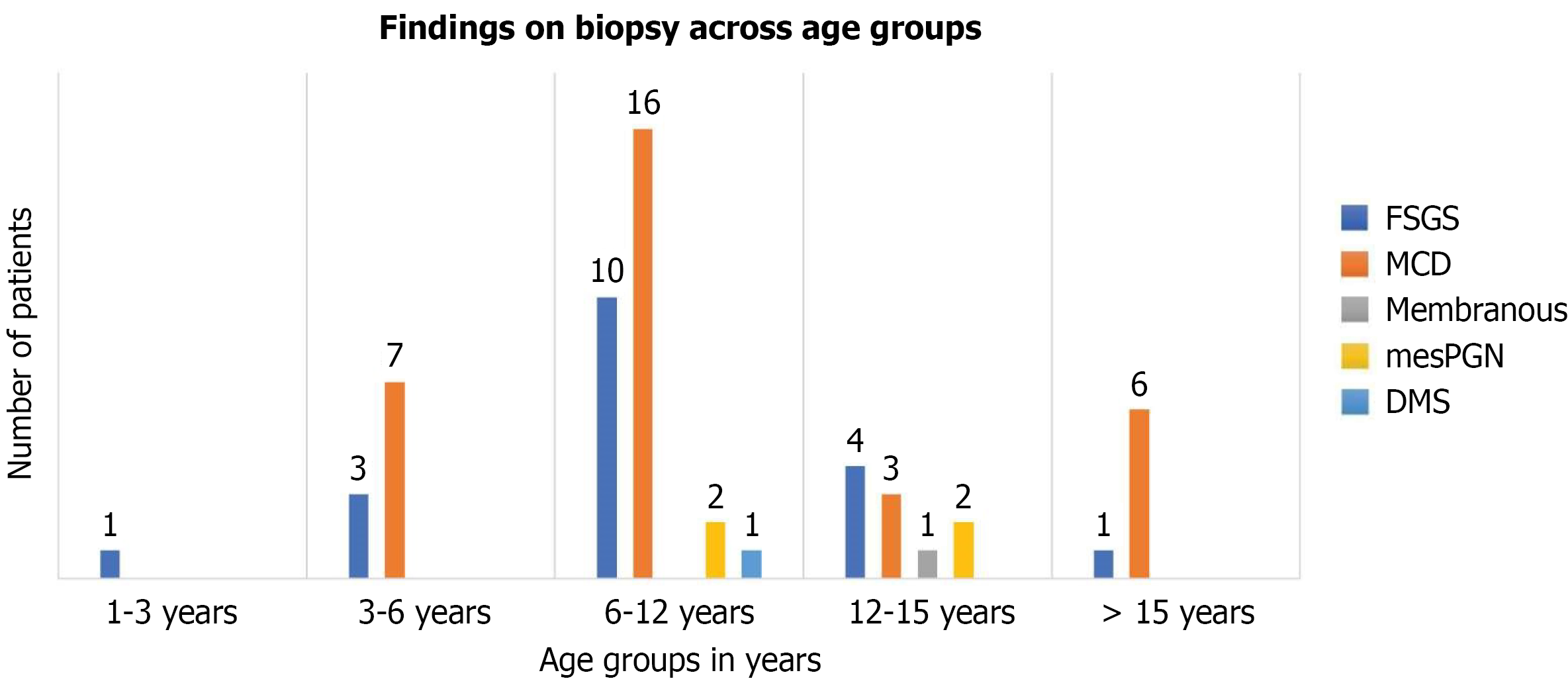

Overall, 81.1% of the patients were classified as having SSNS, whereas 23 (18.9%) patients had SRNS. Table 2 presents the distribution of NS types across age groups. A total of 57 (46.7%) patients underwent kidney biopsy. Table 3 presents the biopsy findings and Figure 2 shows the distribution of the histopathological findings across the age groups. Biopsy was performed if a patient had SD/FR or SRNS, atypical features such as macroscopic hematuria, low complement levels, AKI unrelated to hypovolemia, and features suggestive of vasculitis. Indications for a biopsy were mainly SDNS in 46% (26/57) of the patients, SRNS in 40.0% (23/57), and FRNS in 12% (8/57). The most common histopathological finding among patients with SRNS was focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) 82.6% of biopsies. Diffuse mesangial sclerosis and membranous nephropathy were the less common causes. Two patients had MCD. Genetic testing was conducted in patients with SRNS. Six patients underwent genetic testing, with five testing positive and one testing negative for NPHS2 mutation.

| Current age group, years | Type of NS | Total | |||

| SSNS | SRNS | SDNS | FRNS | ||

| 1–3 | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 5 (100) |

| 3–6 | 19 (59) | 4 (12.5) | 7 (21.8) | 2 (6.3) | 32 (100) |

| 6–12 | 29 (44.6) | 11 (16.9) | 20 (30.7) | 5 (7.7) | 65 (100) |

| 12–15 | 3 (23) | 6 (46.1) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (7.7) | 13 (100) |

| > 15 | 0 | 1 (14.2) | 4 (57.1) | 2 (28.6) | 7 (100) |

| 53 (43.4) | 23 (18.9) | 35 (28.7) | 11 (9) | n = 122 | |

| Histopathological finding | Frequency, n = 57 | Percentage (46.7%) |

| MCD | 32 | 56.1 |

| FSGS | 19 | 33.3 |

| DMS | 1 | 1.8 |

| Membranous | 1 | 1.8 |

| mesPGN | 4 | 7 |

The initial episode was treated using a weight-based formula (2 mg/kg/day) across all three centers for 4 weeks, followed by 40 mg/m2 or 1.5 mg/kg every other day for an additional 4 weeks. The dose was gradually tapered over the following weeks, leading to complete cessation after another 2–3 months. Overall, 21 of the 122 patients (17.2%) received a low steroid dose with a URTI to prevent relapse, especially in those with FRNS. Edema was treated with albumin infusion and furosemide diuretics. Seventy-nine (64.8%) of the patients were receiving vitamin D supplements, most of whom had FRNS and SDNS. Finally, 26 (21.3%) patients were receiving angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors.

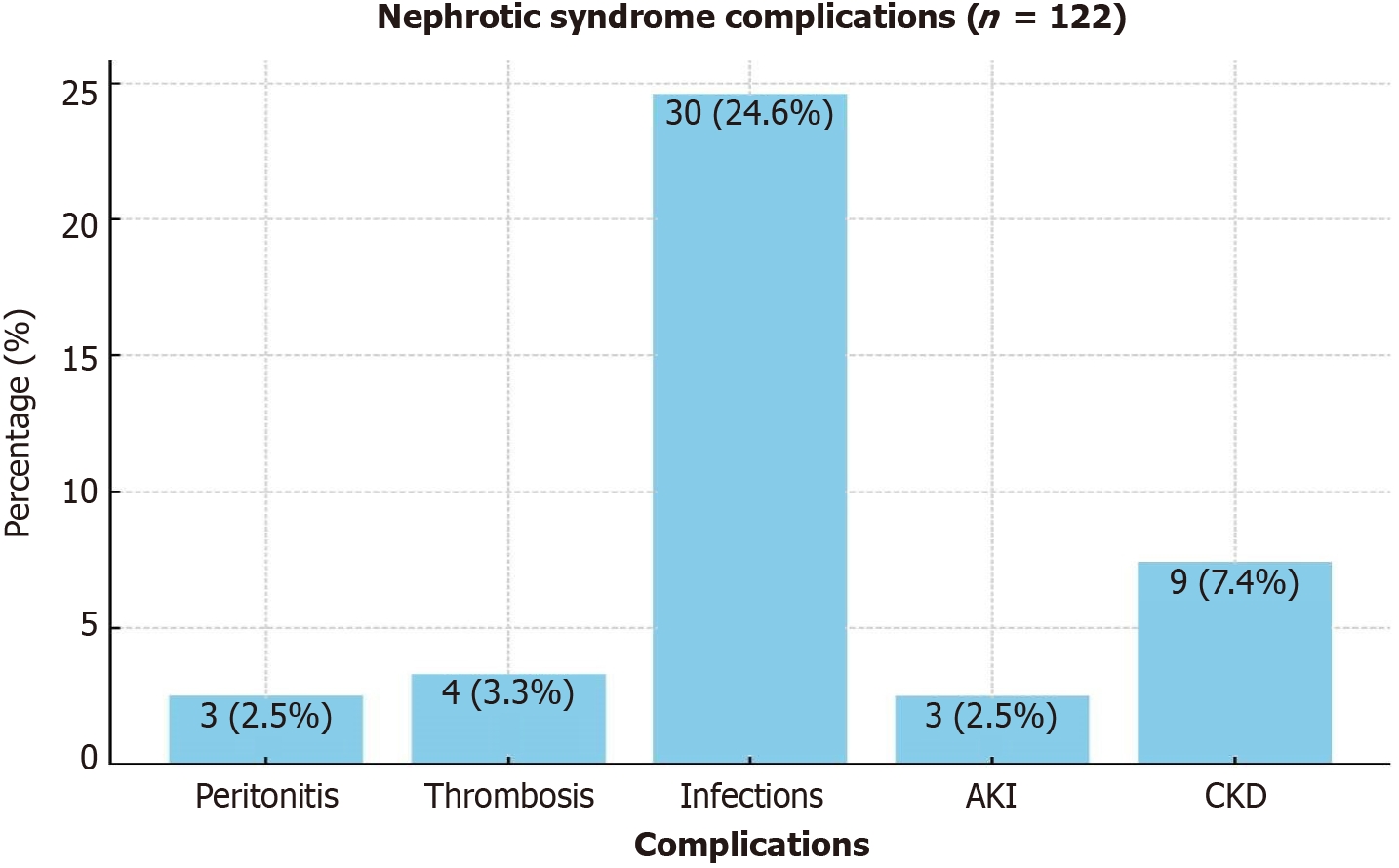

The mean number of relapses per year was 2.6 ± 1.7, and the median time to first relapse was 9 (range, 2-18) months. In total, 49 (40.2%) experienced at least one NS complication (Figure 3), whereas 30 (24.6%) experienced at least one significant infection episode. Urinary tract infections (UTIs) were the most common, constituting 56.7% of cases (17/30). Bacterial and viral pneumonia were observed in 5 (16.7%) patients each, and 3 (10%) patients had peritonitis. Four patients experienced thromboembolic events (deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and sagittal sinus thrombosis) and were treated with anticoagulants. In this cohort, nine (7.4%) patients had CKD stages IV and V, and eight (6.6%) required dialysis. Three patients had AKI, with one requiring hemodialysis owing to acute tubular necrosis on kidney biopsy. Four (3.3%) patients received a kidney transplant. Finally, the mortality rate was 3.3% (4/122), and all patients with ESKD had SRNS.

Overall, 51 (41.8%) of our patients received steroid-sparing medications. Table 4 shows the medications used. CsA was the most commonly used medication, followed by MMF. The mean duration of steroid-sparing medication use was 1.8 ± 0.8 years. Among the patients with SDNS and FRNS, 31 (89%) and 7 (64%), respectively, received at least one steroid-sparing medication. In the entire cohort, 21 (17.2%) patients received multiple steroid-sparing medication treatments and 10 (8.2%) received rituximab. Regarding relapses, 14 (11.5%) patients relapsed at least once while on steroid-sparing medications. Of the 10 patients receiving rituximab, 6 (60%) had SDNS and 2 (20%) had SRNS. Among the patients with SDNS and FRNS, nine (26%) and two (18%) relapsed at least once while on the steroid-sparing treatment, respectively. None of the three patients who received levamisole or the one patient who received cyclophosphamide relapsed, whereas seven (27%) and six (30%) of those who received CsA and MMF, respectively, relapsed. Among the entire cohort, 21 patients (17.2%) experienced significant steroid side effects, with bone pain and aggressive behavior being the most reported side effects.

| Medication | Patients received steroid-sparing medications, n = 51 |

| Cyclosporine | 26 (51.0) |

| Tacrolimus | 1 (2.0) |

| Mycophenolate | 20 (39.2) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1 (2.0) |

| Levamisole | 3 (5.9) |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to describe the outcomes of children with idiopathic NS followed up for 10 years in Jordan. Males were more prevalent in all age groups (P = 0.488), similar results having been reported previously[5,6,12-14]. The median age of onset was 4 years, which is consistent with previous findings from Europe and other countries[13-16].

Most children with NS are steroid-sensitive[10,11]. Many studies have reported frequent relapse rates of 31%–36%, and 7%–22% being SRNS[8,15,17-23]. Our results showed fewer FRNS and more SRNS cases than previously published reports; however, this is comparable to results from other Middle Eastern countries. Mortazavi and Khiavi[14] reported 24.8% of patients had SRNS, 10.3% FRNS, and 8.2% steroid dependent. Similar findings have been reported for other Arab countries[16,18].

The higher number of patients with SDNS and SRNS in our cohort may be attributed to their higher mean age.

Further, 46.7% of patients underwent a biopsy, with MCD being most reported histopathological finding 56%, followed by FSGS in 33.3%. This finding is similar to previous reports[3-5]. Wannous et al[19] reported that among 109 biopsies, the most common histopathological finding was MCD (45%), followed by FSGS (37.6%). Mortazavi and Khiavi[14] reported similar results. All 12 patients in our study with biopsy-confirmed FSGS were steroid resistant. Only two (1.6%) of our patients with SRNS had MCD. Further, 36 (29.5%) had hematuria, and 22 (18%) had hypertension, with 15/36 (42%) and 12/22 (55%) classified as having SRNS, respectively. The hematuria and hypertension rates in our patients were similar to those reported in previous studies in the Middle East[18,19].

Overall, 19 (15.6%) of our patients had a positive family history of NS, a finding similar to the 18.3% rate reported in another study[19]. Eleven of the nineteen patients with biopsy-proven FSGS also had a positive family history of NS (P = 0.01). Five of the six patients with SRNS and a positive family history underwent genetic testing and harbored mutations. The five patients with NPHS2 mutations had biopsy-proven FSGS. These findings are consistent with the previously published data on SRNS[24,25].

No significant associations were found between sex, age at disease onset, NS type, or complications. However, an association was found between sex and the use of multiple steroid-sparing medications. Seventeen (81%) of the 21 patients who required multiple steroid-sparing medications and nine of the ten children who received rituximab were male (P = 0.014).

All three centers used a weight-based formula for the initial treatment of the first episode of the disease. The most recent IPNA guidelines (2021) recommend the interchangeable use of both weight and surface area regimens[7]. When the patients in our study were diagnosed and managed, the 2021 guidelines had not been released. The treatment protocols were based on physicians’ experience and preferences, depending on the available global practice patterns based on the ISKDC[4] and older KDIGO guidelines.

Many studies reported that 16%-67% of patients receive steroid-sparing medications[3,12,15,21]. In our cohort, 51 (41.8%) patients received steroid-sparing medications. No association was found between the center and type of steroid-sparing medication used. All centers used MMF or CsA as the first-line treatment option. Specifically, rituximab was mainly administered to patients with SDNS who were unresponsive to at least one steroid sparing medication. The mean number of relapses per year was 2.6 ± 1.7, and the median time to first relapse was 9 (range, 2–18) months, consistent with findings from other studies[9,14,15].

Several studies have shown that the age of onset is a major factor in predicting relapse, with a younger age of onset, especially < 4–6 years, being associated with a higher likelihood of FRNS and SDNS[9,15,21]. Eighty four (69%) of our patients had an age of onset < 6 years.

Although 15/35 (43%) of patients with SDNS and 5/11(45%) with FRNS had an onset age of < 3 years, this difference was not significant, did not affect the response to steroid treatment, and was not associated with the time to first relapse (P = 0.562).

Furthermore, many studies have reported that the first relapse occurring in the first 6 months after diagnosis is associated with the risk of developing FRNS and SDNS[2,3,21]. Among the 101 patients for whom the time of first relapse was recorded, 37 (37%) experienced a relapse within the first six months. Of them, 29 (78%) had SDNS and 6 (16%) had FRNS. Furthermore, 31/53 (58%) of the patients with infrequent relapses experienced their first relapse after 1 year (P < 0.001).

While patients with SRNS, FRNS, and SDNS are more prone to significant complications[13,25], we found no sig

CKD and ESKD are severe complications. In our cohort, nine patients (7.4%) had CKD stages IV and V, and eight (6.6%) required dialysis, all of whom had SRNS.

However, four (3.3%) patients died. These results are similar to those reported by Mortazavi and Khiavi[14] in northwest Iran, where 5.4% of patients required dialysis and the mortality rate was 4.2%. Similarly, Zaki et al[18] in Kuwait reported mild glomerular filtration rate impairment in 2/55 (3.6%) patients. In a report by Wannous[19], 4.6% of patients died and 10% required dialysis. The rates in the Middle East were higher than those reported by Carter et al[8], where only 1.7% had ESKD.

Infections are a well-known complication of NS, and 24.6% of our patients had infections, with UTIs being the most common. A previous study from Jordan by Akl et al[17] reported an infection rate of 88%. Gulati et al[23] reported a 38% infection rate, with UTIs (13.7%) being the most common infection. The lower infection rate in our cohort may be attributed to the fact that we did not include simple URTIs in our analysis. No significant association was found in age at onset, sex, follow-up time, or treatment center between children who had infections or other complications and those who did not. Rituximab use was significantly associated with infection, as 60% of patients who received rituximab had an infection, and the three patients with peritonitis had received rituximab infusions (P = 0.001).

Prematurity and low birth weight are presumed to be associated with a poorer clinical course in childhood NS, especially regarding the development of SRNS and earlier relapse time[26]. We found low rates of premature and small-for-gestational-age (SGA) children in our cohort, with no association among prematurity, SGA, or any other variables. Therefore, we believe that our results did not reach statistical significance because of the small number of patients with these complications. However, these results emphasize the importance of accurate patient reporting and management.

This is the first multicenter study from Jordan and one of the few regional studies to describe the results of nephrotic syndrome in children. Our findings show higher SRNS and ESKD rates than those in most countries, although comparable to other Middle Eastern results. This information may help in developing national treatment guidelines and improving the quality of care and follow-up for patients with nephrosis. The main limitations of this study are its small sample size and retrospective nature. Further prospective studies are required to confirm these findings.

Our study showed that MCD was the most common NS type, a higher steroid resistance rate and FSGS was the most common cause of SRNS. Regarding outcomes, infections were the most common complications, with urinary UTIs being the most common. This multicenter study of children with NS in Jordan provides valuable information about NS in the Middle East and highlights demographics, treatment protocols, and clinical outcomes.

| 1. | Eddy AA, Symons JM. Nephrotic syndrome in childhood. Lancet. 2003;362:629-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 558] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Vivarelli M, Massella L, Ruggiero B, Emma F. Minimal Change Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:332-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 280] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sinha A, Hari P, Sharma PK, Gulati A, Kalaivani M, Mantan M, Dinda AK, Srivastava RN, Bagga A. Disease course in steroid sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | The primary nephrotic syndrome in children. Identification of patients with minimal change nephrotic syndrome from initial response to prednisone. A report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. J Pediatr. 1981;98:561-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Niaudet P. Long-term outcome of children with steroid-sensitive idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4:1547-1548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gipson DS, Massengill SF, Yao L, Nagaraj S, Smoyer WE, Mahan JD, Wigfall D, Miles P, Powell L, Lin JJ, Trachtman H, Greenbaum LA. Management of childhood onset nephrotic syndrome. Pediatrics. 2009;124:747-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Trautmann A, Boyer O, Hodson E, Bagga A, Gipson DS, Samuel S, Wetzels J, Alhasan K, Banerjee S, Bhimma R, Bonilla-Felix M, Cano F, Christian M, Hahn D, Kang HG, Nakanishi K, Safouh H, Trachtman H, Xu H, Cook W, Vivarelli M, Haffner D; International Pediatric Nephrology Association. IPNA clinical practice recommendations for the diagnosis and management of children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2023;38:877-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Carter SA, Mistry S, Fitzpatrick J, Banh T, Hebert D, Langlois V, Pearl RJ, Chanchlani R, Licht CPB, Radhakrishnan S, Brooke J, Reddon M, Levin L, Aitken-Menezes K, Noone D, Parekh RS. Prediction of Short- and Long-Term Outcomes in Childhood Nephrotic Syndrome. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:426-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hodson EM, Craig JC, Willis NS. Evidence-based management of steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2005;20:1523-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hodson EM, Knight JF, Willis NS, Craig JC. Corticosteroid therapy for nephrotic syndrome in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;CD001533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Watanabe Y, Fujinaga S, Endo A, Endo S, Nakagawa M, Sakuraya K. Baseline characteristics and long-term outcomes of steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome in children: impact of initial kidney histology. Pediatr Nephrol. 2020;35:2377-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Esfahani ST, Madani A, Asgharian F, Ataei N, Roohi A, Moghtaderi M, Rahimzadeh P, Moradinejad MH. Clinical course and outcome of children with steroid-sensitive nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1089-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Dossier C, Lapidus N, Bayer F, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Boyer O, de Pontual L, May A, Nathanson S, Orzechowski C, Simon T, Carrat F, Deschênes G. Epidemiology of idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in children: endemic or epidemic? Pediatr Nephrol. 2016;31:2299-2308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mortazavi F, Khiavi YS. Steroid response pattern and outcome of pediatric idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: a single-center experience in northwest Iran. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2011;7:167-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dossier C, Delbet JD, Boyer O, Daoud P, Mesples B, Pellegrino B, See H, Benoist G, Chace A, Larakeb A, Hogan J, Deschênes G. Five-year outcome of children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: the NEPHROVIR population-based cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:671-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Kaddah A, Sabry S, Emil E, El-Refaey M. Epidemiology of primary nephrotic syndrome in Egyptian children. J Nephrol. 2012;25:732-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Akl KF, Al-Lawama M, Khatib FA, Sleiman MJ, Khuri-Bulos N. The clinical profile of infections in childhood primary nephrotic syndrome. Jordan Med J. 2011;45:303-307. |

| 18. | Zaki M, Helin I, Manandhar DS, Hunt MC, Khalil AF. Primary nephrotic syndrome in Arab children in Kuwait. Pediatr Nephrol. 1989;3:218-20; discussion 221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wannous H. Idiopathic nephrotic syndrome in Syrian children: clinicopathological spectrum, treatment, and outcomes. Pediatr Nephrol. 2024;39:2413-2422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ishikura K, Yoshikawa N, Nakazato H, Sasaki S, Nakanishi K, Matsuyama T, Ito S, Hamasaki Y, Yata N, Ando T, Iijima K, Honda M; Japanese Study Group of Renal Disease in Children. Morbidity in children with frequently relapsing nephrosis: 10-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Nephrol. 2015;30:459-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nakanishi K, Iijima K, Ishikura K, Hataya H, Nakazato H, Sasaki S, Honda M, Yoshikawa N; Japanese Study Group of Renal Disease in Children. Two-year outcome of the ISKDC regimen and frequent-relapsing risk in children with idiopathic nephrotic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8:756-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Tarshish P, Tobin JN, Bernstein J, Edelmann CM Jr. Prognostic significance of the early course of minimal change nephrotic syndrome: report of the International Study of Kidney Disease in Children. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:769-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 242] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gulati S, Kher V, Gupta A, Arora P, Rai PK, Sharma RK. Spectrum of infections in Indian children with nephrotic syndrome. Pediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:431-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Trautmann A, Lipska-Ziętkiewicz BS, Schaefer F. Exploring the Clinical and Genetic Spectrum of Steroid Resistant Nephrotic Syndrome: The PodoNet Registry. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kemper MJ, Valentin L, van Husen M. Difficult-to-treat idiopathic nephrotic syndrome: established drugs, open questions and future options. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33:1641-1649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Konstantelos N, Banh T, Patel V, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Borges K, Hussain-Shamsy N, Noone D, Hebert D, Radhakrishnan S, Licht CPB, Langlois V, Pearl RJ, Parekh RS. Association of low birth weight and prematurity with clinical outcomes of childhood nephrotic syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Pediatr Nephrol. 2019;34:1599-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/