Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107552

Revised: May 2, 2025

Accepted: July 17, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 220 Days and 4.3 Hours

Parental presence in neonatal units (NUs) is essential for infant development and family well-being. A deeper understanding of the factors influencing parental presence is vital and will contribute to the development of targeted interventions and policies that enhance parental engagement in neonatal care, thereby impro

To identify and analyze primary factors influencing parental involvement in their child’s care in a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU).

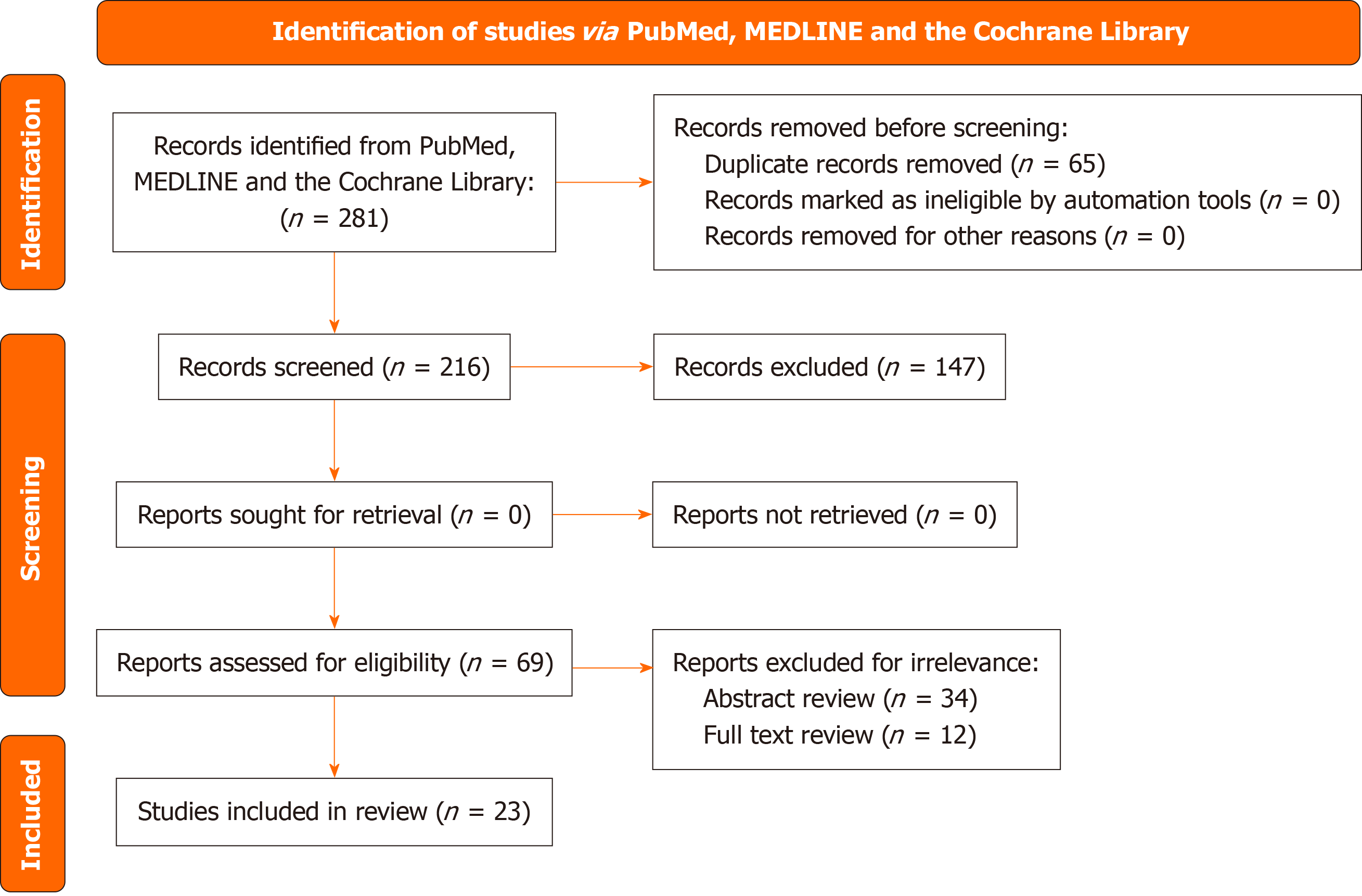

A literature search was conducted using the PubMed, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Library for systematic reviews databases, with the following search terms: “parental presence neonatology”, “couplet care”, “zero separation neonatal care”, “family integrated care”, “couplet care intervention”, “mother-child separation”, “parents newborn togetherness”, “mother-baby care”, “closeness and separation NICU”, “mother-infant interaction NICU”, “kangaroo care”, “dyad mother-in

The literature search yielded 281 articles, out of which 23 were selected for a detailed review. The factors associated with parental presence in NUs were grouped into five main categories: Parents’ socio-demographic and cultural traits; the physical layout and care model of the NUs; the quality of parents’ relationships with the healthcare staff; their active involvement in neonatal care; and the newborn’s health status.

The identification of factors that affect parental presence in NUs is critical for developing effective strategies aimed at encouraging increased parental involvement and ultimately improving neonatal and family outcomes.

Core Tip: Parental involvement in neonatal units has a significant beneficial effect on infant development and family health. This review systematically highlights key determinants of parental presence, categorized according to socio-demographic and cultural aspects, unit physical layout, staff relationships, active parental participation, and infant health status. Recognition of these factors is essential for designing tailored interventions and improving policies to ensure optimal neonatal and family outcomes.

- Citation: Marie A, François-Garret B, Filippi A, Eleni Dit Trolli S, Casagrande F, Lotte JB, Guellec I, Fernandez A. Factors influencing parental presence in neonatal units: A systematic review. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(4): 107552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i4/107552.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107552

The hospitalization of a newborn in a neonatal unit is a major challenge for both the parents and the child. It is often a prolonged experience, marked by significant uncertainty and profound emotional distress[1], occurring during a crucial period for the formation of the parent-child bond—one that can be weakened by the highly specialized medical envi

Numerous studies on this topic have demonstrated the benefits of parental presence for the newborn, particularly in terms of neurodevelopment, neonatal comfort, the formation of the parent-child bond[3], and breastfeeding rates[4]. Additionally, skin-to-skin contact, or the Kangaroo Method, positively affects thermoregulation and stress reduction while also strengthening the attachment between parents and their child[5,6]. From a psychological perspective, parents experience lower levels of anxiety and stress when they are allowed to be present and actively participate in daily care activities, such as feeding and hygiene[5,7–9].

Beyond the individual benefits for the newborn and the parents, parental presence and involvement in neonatal care also positively impact the quality of care and the organization of the neonatal unit, even though adapting to their presence may pose challenges for healthcare providers[10,11]. Studies have shown that it improves communication between caregivers and parents and strengthens mutual trust[11–13].

The couplet care model in neonatal medicine is an approach designed to keep the mother and infant together after birth and even during neonatal hospitalization while fully including parents as key participants in the care of their hospitalized child[14]. This model strengthens the mother-infant bond by encouraging early and prolonged skin-to-skin contact, increases parental involvement in care—allowing parents to fully embrace their role—and reduces the length of neonatal hospital stays[15,16]. This model aligns perfectly with the concept of family-centered care, which is the recommended care model in France according to the Newborn Environment Reflection and Evaluation Group guidelines[17].

Thus, parental presence in neonatal care has been proven essential and has attracted growing interest in the scientific literature. However, despite its demonstrated benefits, it remains inconsistently implemented across units[18,19]. It is, therefore, crucial to identify the factors influencing parental presence in neonatal units and to design care initiatives that promote and facilitate it. This literature review aimed to analyze and synthesize existing knowledge regarding the factors associated with parental presence in neonatal care.

This literature review was conducted by performing searches for systematic reviews in the PubMed and MEDLINE databases, and in the Cochrane Library, using the following keywords: “Parental presence neonatology”; “couplet care”; “zero separation neonatal care”; “family integrated care”; “couplet care intervention”; “mother-child separation”; “parents-newborn togetherness”; “mother-baby care”; “closeness and separation NICU”; “mother-infant interaction NICU”; “kangaroo care”; “dyad mother-infant”; and “newborn integrated care”; without any restriction on publication date or language.

Article identification and selection followed the PRISMA guidelines. Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Studies were included if they focused on neonatal care and explored one or more factors influencing or modulating parental presence, and if they were original research articles (observational studies, randomized controlled trials, before-after studies, or systematic reviews); Studies were excluded if they did not directly address parental presence in neonatal units or if they only focused on clinical outcomes without considering parental involvement.

The database search for this literature review began on December 10, 2024, with the final search conducted on April 10, 2025. A total of 281 articles were identified through the database searches.

After removing 65 duplicates, 216 articles remained for screening. No records were excluded by automated tools. The titles of the articles were then reviewed for relevance to the subject, resulting in 69 articles being retained for the next stage. After reviewing the abstracts, 34 articles were excluded.

The remaining 35 articles were analyzed in full for relevance. Among these, 12 articles were considered irrelevant (as they did not directly address the topic) and were excluded from the analysis. In total, 23 articles were included in this review.

The PRISMA flow diagram is reported in Figure 1.

The qualitative study by Van Veenendaal et al[18] sought to understand the facilitators and barriers to parent–infant closeness in NICUs. It involved semi-structured interviews with healthcare professionals in 46 hospitals across 19 different countries and highlighted the importance of socio-demographic factors. This observational study found that mother-infant separation occurred in 93% of cases, despite the implementation of family-centered care programs. Several factors were identified as modulators of parental presence, including the family’s resources (financial means and access to transportation to the hospital), as well as parental education regarding the benefits and importance of their presence for their newborn.

The study by Schmid et al[19] is a qualitative, single-center study based on semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions with 20 parents and 21 healthcare professionals in a Swiss neonatal unit. The results highlighted both facilitators and barriers to parental presence, notably relating to socio-demographic factors. These included time ma

Clarkson et al[20] conducted a cross-sectional study that aimed to identify factors associated with paternal involvement in the NICU. Participants included 80 biological fathers of infants hospitalized in an NICU in the United States. Fathers completed a survey assessing their involvement and the factors associated with it. The authors reported that factors positively influencing fathers’ involvement in neonatal intensive care units included age, marital status, and multiple births.

Gonya et al[21] focused on 32 extremely premature neonates and their mothers. Their study aimed to identify the factors that affected how often mothers visited and took part in skin-to-skin care in a Level III NICU, using standard tools such as the Parental Stressor Scale and the Parent-Staff Communication Rating Scale, along with self-reported de

In addition to family composition and distance to the hospital, Neu et al[22] emphasized the importance of practical and emotional support provided to parents by their friends or family. The study employed a qualitative descriptive approach based on open-ended interviews that compared the experiences of mothers in NICUs that had implemented Family-Centered Care as standard practice with the experiences of mothers two decades earlier. The sample consisted of 14 mothers of infants born before 32 weeks of postconceptional age. In their article, the support provided to mothers by family and friends is identified as a crucial aspect of the NICU experience. Mothers with a strong support network felt more comfortable and better prepared to cope with the stress of their infant’s hospitalization. In contrast, mothers who were isolated or lacked family support reported feeling lonelier and found it more difficult to fully engage in their baby’s care.

In the study by Head Zauche et al[23], 66 preterm infants were recruited from two Level III NICUs in the United States. This prospective cohort study was designed to identify socio-demographic, clinical, environmental, and maternal psychological factors that predict parental presence in NICUs, using visitation logs and medical records. The study found that factors such as the number of children at home, the presence of neurological comorbidities, the type of room, surgical history, and the perceived stress of the NICU had a significant influence on parental presence.

The physical layout and regulations of neonatal units play a crucial role in parental engagement with hospitalized newborns[7,18,19,24–27]. Historically, most neonatal departments consisted of multiple-bed rooms (“open-bay units”). Numerous studies have examined the impact of providing individual rooms (family rooms)[7,18,23,24,27–30]. These studies show that parental presence significantly increases in units with individual rooms, which also encourages greater parental participation in daily care.

Tandberg et al[7] designed a multicenter observational study involving 328 preterm infants and their parents across 11 NICUs in six European countries. The study’s goal was to assess the extent of parental presence and parent–infant closeness in NICUs and to identify the factors that affect these aspects. Parents kept daily diaries over the first 2 weeks of hospitalization, recording the duration of their presence, skin-to-skin contact, and holding activities. The average continuous presence was 21 hours for mothers and 16 hours for fathers in individual rooms, compared to 7 hours and 5 hours, respectively, in multiple-bed rooms. Additionally, the average daily duration of skin-to-skin contact was 6 hours in individual rooms, compared to 4 hours in multiple-bed rooms (P < 0.001).

Van Veenendaal et al[24] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis involving 1850 preterm infants, 1549 mothers, and 379 fathers from 11 different countries. Their review assessed the impact of neonatal unit design—specifically, single-family rooms vs open-bay units—on parental well-being. Findings indicate that single-family rooms are associated with increased parental presence, involvement, and skin-to-skin care.

The study by Lehtonen et al[27] included 4662 neonates from 331 NICUs in 10 countries. This international cohort study investigated whether the availability of single-family rooms in NICUs was associated with improved neonatal outcomes. The study found that only 13.3% of the surveyed units provided such rooms, highlighting the lack of facilities that allow continuous parental presence. Furthermore, the presence of infant-parent rooms was associated with improved neonatal outcomes, including lower odds of mortality or major morbidity and shorter hospital stays. These findings suggest that such facilities may contribute to greater parental involvement in neonatal care.

Pineda et al[28] conducted a quasi-experimental study that explored the relationship between the type of NICU room and parental behavior, such as hours of visitation and frequency of holding, as well as maternal health outcomes. The study focused on 81 premature infants who were assigned either to single-patient rooms or open-bay areas in a Level III NICU, depending on bed availability. The findings indicated that when infants were in single-patient rooms, there was a significant increase in the number of hours of parental visits during the first 4 weeks of life (P = 0.02).

NICU regulations also have a significant impact on parental visits. Nowadays, most units allow parents to remain with their children and visit them at any time, day or night. However, this is not yet the case in all neonatal units across Europe[18]. In the study by Van Veenendaal et al[18], which primarily involved European countries, 71% of units authorized unrestricted visiting hours (24/7) for parents.

In exceptional circumstances, such as the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, hospital restrictions limited parental presence in neonatal units. The study by Kostenzer et al[26], based on a questionnaire sent to 1148 parents whose children were hospitalized in neonatal care units during the first year of the pandemic in 12 different countries, demonstrated that parental presence was severely impacted by these restrictions, with 27% of respondents reporting that they were not allowed to visit their child.

The study by Giordano et al[25] examined the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on a neonatal unit in Austria, where visits were limited to one parent at a time and only once per day. Consequently, these measures significantly reduced (P < 0.001) the presence of both parents in the unit during this period compared to the pre-lockdown period. Interestingly, maternal presence actually increased during the pandemic, with a significant rise in the time spent in skin-to-skin contact (P < 0.001).

Coats et al[10] conducted semi-structured interviews that explored nurses’ perceptions of the benefits and challenges of implementing family-centered care in intensive care units. Their sample included 10 nurses from pediatric, cardiac, and neonatal intensive care units. The nurses reported a significant impact of unit policies (such as 24-hour access) and physical layout (transition to individual rooms) on their ability to provide high-quality, family-centered care.

Other unit policies also play a crucial role in encouraging parental presence. Several studies reported that parental presence was influenced not only by providing beds near the child or nearby accommodations but also by offering free hospital parking[18,19], free meals for parents, and breast pump kits[18]. These studies show that modifications in the unit’s physical layout and in hospital policies are essential for the development of parent-newborn couplet care.

The study by Curley et al[31] is an integrative literature review that included 20 articles. The authors investigated the barriers to implementing the couplet care model and identified several obstacles related to the unit’s physical layout and institutional factors, such as resource limitations, restrictive hospital policies, lack of staff training, and concerns about safety and workload management.

Van Veenendaal et al[32] conducted a prospective, multicenter cohort study in the Netherlands between May 2017 and January 2020, which included 296 mothers of preterm infants. Their research compared the maternal stress levels at discharge associated with two care models: The Family Integrated Care model, which allowed continuous mother-infant closeness in single-family rooms, and standard neonatal care in open-bay units. They demonstrated a significantly higher level of maternal presence (over 8 hours per day) and involvement in the group that received family-centered care (which included individual rooms and joint care for the mother and child) compared to the group that received standard care.

The studies by Van Veenendaal et al[18] and Schmid et al[19] identified the relationship between parents and the healthcare team as a key factor in promoting parent-child closeness in neonatal care units. This relationship primarily relies on effective communication. Open and transparent conversations between parents and healthcare providers foster mutual trust and encourage parental involvement in the child’s care. Parents and healthcare providers interviewed in these studies emphasized the importance of making parents feel welcome in these units. Once again, cultural aspects were found to be crucial, as it is essential for both the healthcare team and parents to share a common understanding of the importance of parental presence in the unit. Finally, these studies reported that the support and guidance provided by healthcare professionals affirmed the parents in their role, which served as an incentive for them to be more present.

Treherne et al[30] conducted a qualitative descriptive study aimed at exploring how parents perceive moments of closeness with, and separation from, their preterm infants during hospitalization. They included 20 parents of preterm infants admitted to a Level III NICU. Using a smartphone application developed for the study, the parents recorded their experiences over a 24-hour period. Several factors were identified as contributing to increased parental presence at their infant’s bedside, including support from healthcare professionals. The study confirmed that empathetic support from staff and open communication encouraged greater parental involvement and increased time spent with the infant. These factors highlight the importance of a supportive hospital environment and strong collaboration between parents and healthcare professionals in ensuring sustained parental presence in the NICU.

In the study by Curley et al[31], healthcare professionals stressed the importance of training their teams in family-centered care and couplet care. The study found that a lack of adequate training in joint care prevented healthcare professionals from providing it effectively. Furthermore, some of them may have been reluctant to implement this care model due to a lack of confidence, skills, or awareness of its benefits[31].

Similarly, the study by Larsen et al[33] highlighted that training of the various healthcare teams was a key component of couplet care. Their study included 21 healthcare professionals comprising neonatologists, obstetricians, midwives, and nurses who participated in four focus group interviews conducted at a tertiary referral university hospital in Denmark. This qualitative study aimed to explore healthcare professionals’ expectations, concerns, and educational needs regarding the implementation of mother–newborn couplet care, particularly with newborns requiring intensive care.

Casper et al[34] published a reflective paper based on a literature review and clinical observations, which explores the barriers to early parental involvement in neonatal care. The authors highlight several limiting factors, including an inadequate hospital environment (such as the absence of single-family rooms, constant noise, bright lighting, and lack of privacy), inconsistent parental access policies, and a lack of staff training to support family inclusion. A central issue identified was the persistence of care models focused primarily on healthcare professionals, where parental involvement is sometimes viewed as secondary or even disruptive. As a result, parents are not always invited to participate in care, which can hinder early bonding and make them feel like outsiders in the NICU.

Active parental involvement in their child’s care in neonatal units is essential, as it strengthens the parent-child bond, reduces parental stress, enhances parents’ skills, and reinforces their role[35], all of which have a positive impact on parental presence within the unit[19,32].

The study by Ponthier et al[12] investigated practices in neonatal units regarding parental presence during painful or invasive procedures. This multicenter observational study conducted in France recruited 471 healthcare professionals. The results demonstrated significant variability in practices depending on the type of procedure, the institution, and the experience of the healthcare providers. For example, parental presence was often permitted during capillary or venous blood sampling but was more restricted during more invasive procedures such as intubation or the insertion of central catheters. Most professionals also reported that the presence of parents during these procedures increased their engagement in the child’s routine care (71.6%), improved their relationship with the healthcare team (57.2%), and strengthened the parent-child bond (46.9%).

The study by Abdel-Latif et al[11], a randomized controlled trial involving 72 parents and 39 healthcare professionals, examined the impact of parental presence and participation during bedside medical rounds in neonatal intensive care units. The study found that 95% of parents and 90% of healthcare providers were in favor of parental presence during these visits. The main barriers to active parental participation were primarily organizational (e.g., medical visit schedules, limited space, shared rooms affecting confidentiality) and relational (e.g., concerns that parental presence might slow down rounds, complicate decision-making, or make parents feel inferior or intrusive). Group discussions revealed that parental involvement in their child’s care contributed to better communication with the medical team, reduced parental stress, and improved understanding of the newborn’s health condition.

Clarkson et al[20] reported that fathers involved in their child’s care—such as being present during delivery or performing skin-to-skin contact—were also more present in neonatal units, and that their involvement increased their confidence. Parental involvement in care can take various forms. He et al[36] developed an intervention that fosters “close collaboration with parents”. The intervention was a structured 18-month training program for neonatal staff im

During visits to their hospitalized child, parents sometimes contribute to adverse events (e.g., accidental disconnection of tubing, hygiene errors), as noted by Frey et al[37] in their retrospective survey of all the critical incidents involving parents from January 1, 2002 to August 31, 2007, in a Swiss children’s hospital. However, the authors observed that parents can also play a crucial role in identifying and reporting errors.

The study by Hoeben et al[29], examined the perspectives of 344 parents, 98% of whom were mothers, whose infants were hospitalized in Dutch neonatal wards between 2015 and 2020. In this cross-sectional study, an online survey was used to explore how parents perceived their involvement in family-centered care. The study’s aim was to identify areas for improvement and ensure optimal parental engagement in neonatal units. Despite implementation of the family-centered care model, 58% of parents found it difficult to bond with their newborn, and 79% felt a sense of separation. The primary area for improvement highlighted by parents was greater involvement in routine care and in decision-making processes concerning their child.

Head Zauche et al[23] demonstrated a direct relationship between the presence of neurological comorbidities or previous surgical history and parental presence. The average time parents were present was 1.9 times higher when infants did not have neurological comorbidities. They were also more involved if the infant had not undergone any surgical procedure.

The study by Clarkson et al[20] showed that duration of hospitalization is also a factor that affects parental presence, while Curley et al[31] found that the level of care required by the child was a barrier to the implementation of couplet care. The health status of a newborn hospitalized in a neonatal unit and the level of care required have a direct impact on parental presence within the care unit, affecting both the frequency and duration of their presence[20,23]. To reach the goal of optimal parental presence, it is essential that healthcare teams provide individualized support strategies adapted to each family’s needs[31].

In our literature review, we identified five key groups of factors that affect parental presence and should be considered when designing strategies to increase parental involvement: Parents’ socio-demographic and cultural characteristics, the unit’s physical layout and regulations, the parent-healthcare team relationship, parental participation in the child’s care, and the newborn’s health status.

The benefits of parental presence for both newborns and their parents are well documented in the literature, yet studies show considerable variability in the amount of time parents spend visiting in neonatal units[18]. Overall, studies have shown that socio-demographic factors can affect parents’ ability to be present with their hospitalized newborn, particularly their level of education, available resources, professional situation, cultural background, and family composition. For instance, financial or work-related constraints may limit the time parents can spend at the hospital, while a higher level of education may be associated with a better understanding of medical issues leading to more active involvement[18,19,22,23]. Furthermore, single-parent families and those with other children may face additional challenges in organizing visits to the neonatal unit[19]. It is, therefore, essential to take socio-demographic factors into account in neonatal units to provide appropriate support, facilitate parental presence, and encourage active parental involvement in their newborn’s care[18,20,21].

Historically, neonatal intensive care units were highly medicalized environments where parental access was restricted, often justified by the need to maintain sterility and ensure optimal care for the newborn. However, recent studies have shown that parental presence is, on the contrary, beneficial for the infant—particularly during invasive and painful procedures[12]. While there is a risk that parents may cause adverse events during visits (such as disconnecting tubes or breaches in hygiene protocols), they can also identify and report errors, thereby contributing to the safety and quality of care[37].

The physical layout of neonatal units also warrants reconsideration, as evidence from the literature shows a clear increase in parental presence when units are equipped with single-family rooms. These rooms offer greater privacy and autonomy in an environment that more closely resembles the home[24,27,28]. Other measures have also proven effective, such as providing breast pump kits, free hospital parking, and complimentary meals for parents staying with their hospitalized infant[18,19].

Family-centered care models and the principle of couplet care are increasingly recognized as cornerstones of neonatal care; however, several obstacles to their implementation persist[14,16,31,38,39]. The concept of couplet care was first introduced in Scandinavian countries[14], and is now being adopted in highly developed countries, such as France, albeit with some difficulty[34]. The implementation of these models requires significant changes, both in the physical layout of neonatal units and in the training of healthcare professionals[14,34,38,40].

Prior to the development of family-centered care, neonatal care models primarily focused on healthcare professionals, and parental involvement was often considered secondary or even disruptive. Within this framework, NICU design was largely centered on the technical aspects of medical care[34], with little consideration for the emotional and sensory needs of neonates or the importance of parental presence. Parents were often viewed as potential sources of infection and adverse events[35]. As a result, the critical importance of early parent–infant interactions was underestimated. Re

Societal factors also act as barriers to parental presence in NICUs, particularly with respect to parental leave enti

The Kangaroo Mother Care method was first introduced in 1978 in Colombia as an alternative to incubators for premature or low-birth-weight newborns. The World Health Organization has encouraged developing countries to adopt this method, particularly when medical resources are limited[43]. However, few studies have been conducted in these regions to date, and further research focusing on the specific barriers to implementing family-centered care in developing countries would be highly valuable.

Several studies consistently highlight the critical role of the relationship between healthcare staff and parents in promoting sustained parental presence and involvement in neonatal care[31,33,34]. This relationship is a key element during a newborn’s hospitalization in a neonatal unit. It enables parents to actively participate in daily care, which strengthens the parent–infant bond and contributes to the infant’s development. Moreover, appropriate support from healthcare providers helps parents cope with the stress and anxiety associated with their child’s hospitalization by encouraging them to maintain a continuous presence and empowering them to reclaim their central role as parents[19].

Active parental involvement in routine neonatal care benefits both the infant and the parents and encourages them to be even more present and engaged throughout the hospital stay. By participating directly in daily care activities such as feeding, diaper changing, or bathing, parents establish and strengthen the emotional bond with their newborn[13,16,25]. Their engagement helps reduce feelings of helplessness, thereby alleviating the stress and anxiety associated with separation and uncertainty[35]. Through this involvement, parents acquire new skills and develop confidence in their ability to care for their child, which is important for the transition from hospital to home and the discharge process. To encourage such parental participation, it is essential to create a more welcoming environment for families, train healthcare teams to effectively include parents in care, and clearly inform parents about their role and place in their child’s care journey[31,34].

The health status of the newborn also plays a significant role in modulating parental presence in neonatal care units. Studies show that infants with more complex medical needs—such as neurological comorbidities, surgical histories, or conditions requiring higher levels of care—tend to receive less frequent or shorter visits from their parents[23,31]. These medical challenges may create physical, emotional, or logistical barriers that limit parents’ ability to remain at the bedside. Therefore, the severity of the infant’s condition must be considered when developing strategies to support and encourage parental involvement.

A final observation is that in cases where parental presence is difficult to implement, expanding home hospitalization may offer a potential solution. This represents a promising avenue for further study.

Our review presents several strengths, notably the inclusion of a wide range of studies with diverse designs. We considered observational studies, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and before-and-after studies, all with substantial sample sizes, which enabled a thorough analysis of the available data. Furthermore, the review encompassed research conducted in multiple countries worldwide, which enhances the generalizability of the findings. Lastly, the consistency of outcomes throughout the included studies strengthens the validity of the results, suggesting that the observed effects are not limited to specific contexts. Despite the methodological diversity of the studies, the convergence of findings confirms the relevance of the identified factors in modulating parental involvement. The various factors influencing parental presence identified in our literature review have also been emphasized in previous reviews on the topic[24,31,34].

However, our review also has limitations. Most of the included studies were descriptive, which limits the ability to establish causal relationships. Additionally, the studies focused on subjective factors, such as individual perceptions and experiences, which may have introduced bias and reduced the generalizability of the conclusions. Finally, there is a notable scarcity of studies examining the socio-economic dimensions and the costs associated with policies aimed at encouraging parental presence in neonatal units.

This literature review identified five key groups of factors that influence parental presence and should be considered when designing strategies to encourage parental involvement: Parents’ socio-demographic and cultural characteristics; the unit’s physical layout and regulations; the parent-healthcare team relationship; parental participation in the child’s care; and the newborn’s health status. Continued efforts are therefore essential in each of these areas to remove existing barriers and ensure that parents are welcomed in neonatal units and actively involved in their child’s care, which has been consistently shown to benefit both the child and the parents.

| 1. | Whittingham K, Boyd RN, Sanders MR, Colditz P. Parenting and Prematurity: Understanding Parent Experience and Preferences for Support. J Child Fam Stud. 2014;23:1050-1061. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Devouche E, Buil A, Genet MC, Bobin-Bègue A, Apter G. [Supporting the establishment of the parent-child bond in cases of prematurity]. Soins Pediatr Pueric. 2017;38:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Flacking R, Lehtonen L, Thomson G, Axelin A, Ahlqvist S, Moran VH, Ewald U, Dykes F; Separation and Closeness Experiences in the Neonatal Environment (SCENE) group. Closeness and separation in neonatal intensive care. Acta Paediatr. 2012;101:1032-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cuttini M, Croci I, Toome L, Rodrigues C, Wilson E, Bonet M, Gadzinowski J, Di Lallo D, Herich LC, Zeitlin J; EPICE Research Group. Breastfeeding outcomes in European NICUs: impact of parental visiting policies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2019;104:F151-F158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zych B, Błaż W, Dmoch-Gajzlerska E, Kanadys K, Lewandowska A, Nagórska M. Perception of Stress and Styles of Coping with It in Parents Giving Kangaroo Mother Care to Their Children during Hospitalization in NICU. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:12694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | World Health Organization. Kangaroo mother care: A practical guide. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2003. |

| 7. | Tandberg BS, Flacking R, Markestad T, Grundt H, Moen A. Parent psychological wellbeing in a single-family room versus an open bay neonatal intensive care unit. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0224488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kamphorst K, Brouwer AJ, Poslawsky IE, Ketelaar M, Ockhuisen H, van den Hoogen A. Parental Presence and Activities in a Dutch Neonatal Intensive Care Unit: An Observational Study. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2018;32:E3-E10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Franck LS, Spencer C. Parent visiting and participation in infant caregiving activities in a neonatal unit. Birth. 2003;30:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Coats H, Bourget E, Starks H, Lindhorst T, Saiki-Craighill S, Curtis JR, Hays R, Doorenbos A. Nurses’ Reflections on Benefits and Challenges of Implementing Family-Centered Care in Pediatric Intensive Care Units. Am J Crit Care. 2018;27:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abdel-Latif ME, Boswell D, Broom M, Smith J, Davis D. Parental presence on neonatal intensive care unit clinical bedside rounds: randomised trial and focus group discussion. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F203-F209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ponthier L, Ensuque P, Guigonis V, Bedu A, Bahans C, Teynie F, Medrel-Lacorre S. Parental presence during painful or invasive procedures in neonatology: A survey of healthcare professionals. Arch Pediatr. 2020;27:362-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patriksson K, Nilsson S, Wigert H. Conditions for communication between health care professionals and parents on a neonatal ward in the presence of language barriers. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2019;14:1652060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Klemming S, Lilliesköld S, Arwehed S, Jonas W, Lehtonen L, Westrup B. Mother-newborn couplet care: Nordic country experiences of organization, models and practice. J Perinatol. 2023;43:17-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bjerregaard M, Axelin A, Carlsen ELM, Birk HO, Poulsen I, Palisz P, Kallemose T, Brødsgaard A. Evaluation of a complex couplet care intervention in a neonatal intensive care unit: A mixed methods study protocol. Pediatr Investig. 2024;8:139-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patriksson K, Selin L. Parents and newborn “togetherness” after birth. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2022;17:2026281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Thébaud V, Bian F, Le Pors C, Berne Audéoud F, Sizun J; groupe GREEN de la SFN. Family-centered rounds in neonatal units. [cited 11 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.societe-francaise-neonatalogie.com/_files/ugd/d8ff38_a54fa16c6f304fc28b628d2570c13fa8.pdf. |

| 18. | van Veenendaal NR, Labrie NHM, Mader S, van Kempen AAMW, van der Schoor SRD, van Goudoever JB; CROWN Study Group. An international study on implementation and facilitators and barriers for parent-infant closeness in neonatal units. Pediatr Investig. 2022;6:179-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schmid SV, Arnold C, Jaisli S, Bubl B, Harju E, Kidszun A. Parents’ and neonatal healthcare professionals’ views on barriers and facilitators to parental presence in the neonatal unit: a qualitative study. BMC Pediatr. 2024;24:268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Clarkson G, Gilmer MJ, Moore E, Dietrich MS, McBride BA. Cross-sectional survey of factors associated with paternal involvement in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28:3977-3990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gonya J, Nelin LD. Factors associated with maternal visitation and participation in skin-to-skin care in an all referral level IIIc NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:e53-e56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Neu M, Klawetter S, Greenfield JC, Roybal K, Scott JL, Hwang SS. Mothers’ Experiences in the NICU Before Family-Centered Care and in NICUs Where It Is the Standard of Care. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20:68-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Head Zauche L, Zauche MS, Dunlop AL, Williams BL. Predictors of Parental Presence in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20:251-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | van Veenendaal NR, van Kempen AAMW, Franck LS, O’Brien K, Limpens J, van der Lee JH, van Goudoever JB, van der Schoor SRD. Hospitalising preterm infants in single family rooms versus open bay units: A systematic review and meta-analysis of impact on parents. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Giordano V, Fuiko R, Witting A, Unterasinger L, Steinbauer P, Bajer J, Farr A, Hoehl S, Deindl P, Olischar M, Berger A, Klebermass-Schrehof K. The impact of pandemic restrictive visiting policies on infant wellbeing in a NICU. Pediatr Res. 2023;94:1098-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kostenzer J, von Rosenstiel-Pulver C, Hoffmann J, Walsh A, Mader S, Zimmermann LJI; COVID-19 Zero Separation Collaborative Group. Parents’ experiences regarding neonatal care during the COVID-19 pandemic: country-specific findings of a multinational survey. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e056856. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lehtonen L, Lee SK, Kusuda S, Lui K, Norman M, Bassler D, Håkansson S, Vento M, Darlow BA, Adams M, Puglia M, Isayama T, Noguchi A, Morisaki N, Helenius K, Reichman B, Shah PS; International Network for Evaluating Outcomes of Neonates (iNeo). Family Rooms in Neonatal Intensive Care Units and Neonatal Outcomes: An International Survey and Linked Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2020;226:112-117.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pineda RG, Stransky KE, Rogers C, Duncan MH, Smith GC, Neil J, Inder T. The single-patient room in the NICU: maternal and family effects. J Perinatol. 2012;32:545-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hoeben H, Obermann-Borst SA, Stelwagen MA, van Kempen AAMW, van Goudoever JB, van der Schoor SRD, van Veenendaal NR. ‘Not a goal, but a given’: Neonatal care participation through parents’ perspective, a cross-sectional study. Acta Paediatr. 2024;113:1246-1256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Treherne SC, Feeley N, Charbonneau L, Axelin A. Parents’ Perspectives of Closeness and Separation With Their Preterm Infants in the NICU. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2017;46:737-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Curley A, Jones LK, Staff L. Barriers to Couplet Care of the Infant Requiring Additional Care: Integrative Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;11:737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | van Veenendaal NR, van Kempen AAMW, Broekman BFP, de Groof F, van Laerhoven H, van den Heuvel MEN, Rijnhart JJM, van Goudoever JB, van der Schoor SRD. Association of a Zero-Separation Neonatal Care Model With Stress in Mothers of Preterm Infants. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e224514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Larsen JN, Navne LE, Hansson H, Maastrup R, Poorisrisak P, Sørensen JL, Broberg L. Mother-newborn couplet care and the expectations, concerns and educational needs of healthcare professionals: a qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e086572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Casper C, Raynal F, Glorieux I, Montjaux N, Bloom M. Quels sont les obstacles à l'implication précoce des parents en néonatologie ? Devenir. 2012;24:55-59. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Casper C, Caeymaex L, Dicky O, Akrich M, Reynaud A, Bouvard C, Evrard A, Kuhn P; Groupe de réflexion et d’évaluation sur l’environnement du nouveau-né de la Société française de néonatologie. Parental perception of their involvement in the care of their children in French neonatal units. Arch Pediatr. 2016;23:974-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | He FB, Axelin A, Ahlqvist-Björkroth S, Raiskila S, Löyttyniemi E, Lehtonen L. Effectiveness of the Close Collaboration with Parents intervention on parent-infant closeness in NICU. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Frey B, Ersch J, Bernet V, Baenziger O, Enderli L, Doell C. Involvement of parents in critical incidents in a neonatal-paediatric intensive care unit. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:446-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Roué JM, Kuhn P, Lopez Maestro M, Maastrup RA, Mitanchez D, Westrup B, Sizun J. Eight principles for patient-centred and family-centred care for newborns in the neonatal intensive care unit. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017;102:F364-F368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kokorelias KM, Gignac MAM, Naglie G, Cameron JI. Towards a universal model of family centered care: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Klemming S, Lilliesköld S, Westrup B. Mother-Newborn Couplet Care from theory to practice to ensure zero separation for all newborns. Acta Paediatr. 2021;110:2951-2957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Eurécia. Le congé parental à travers le monde. [cited 7 July 2025]. Available from: https://www.eurecia.com/blog/conge-parental-monde/. |

| 42. | Tchagbele O, Djadou K, Segbedji K, Agbeko F, Azouma K, Atakouma D, Agbèrè A. Évaluation de la qualité des soins maternels kangourou au centre hospitalier universitaire Sylvanus-Olympio de Lomé au terme de six ans de mise en place. Périnat. 2019;11:135-141. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Care of Preterm or Low Birthweight Infants Group. New World Health Organization recommendations for care of preterm or low birth weight infants: health policy. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;63:102155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/