Published online Dec 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107346

Revised: April 17, 2025

Accepted: June 11, 2025

Published online: December 9, 2025

Processing time: 225 Days and 0.5 Hours

Unintended pregnancy occurs when an individual or couple conceives without planning or desire, which can potentially affect a child’s physical, mental, and social well-being. This can then lead to long-term socioeconomic challenges for families and communities. Although its impact on child growth and development is a pressing concern, research remains limited particularly in multicenter settings.

To examine the long-term consequences of unintended pregnancy on the critical years of early childhood growth and development.

This analytical observational study employed a case-control design and was conducted in research centers across Indonesia, encompassing those located in Central Java, Lampung, Bali, and West Nusa Tenggara. A total of 700 children aged ≤ 5 years with histories of intended or unintended pregnancies participated. Data collection involved structured interviews and direct anthropometric and developmental assessments. Data analyses were conducted using multivariate statistics and partial least squares structural equation modeling.

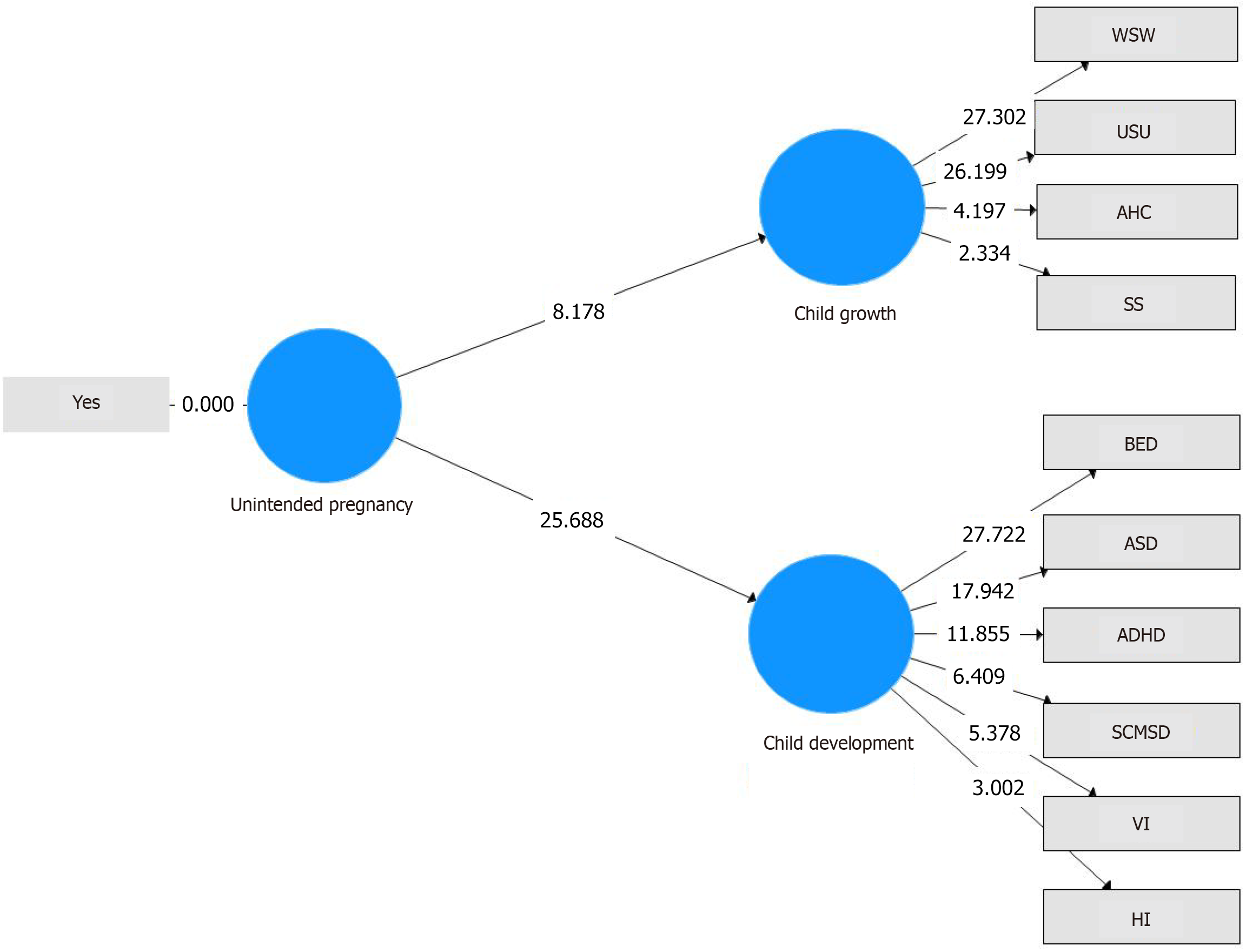

Unintended pregnancy was found to have a statistically significant effect on both child growth (t = 8.178; P < 0.001) and child development (t = 25.688; P < 0.001). Key growth problems identified included underweight, undernutrition, abnormal head circumference, and stunting. Developmental challenges prominently associated with unintended pregnancy included behavioral and emotional disorders, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, social and motor skill deficits, as well as visual and hearing impairments.

Unintended pregnancy significantly affects child growth and development, underscoring the need for early intervention, quality prenatal care, and strengthened family planning policies.

Core Tip: Unintended pregnancy was found to significantly affect the resultant children’s growth and development. The children of unplanned pregnancies more frequently presented undernutrition, abnormal growth patterns, emotional disorders, and developmental delays. To mitigate such risks to the child’s growth and development, early intervention, comprehensive prenatal care, and improved access to family planning are essential.

- Citation: Yanti L, Surtiningsih, Ardiyani FHN, Sekarini NNAD, Susanti D, Mustaan, Murniati, Supriyadi, Santosa A. Long-term consequences of unintended pregnancy: Impacts on early childhood growth and development in a multicenter study. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(4): 107346

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i4/107346.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i4.107346

Unintended pregnancy refers to a pregnancy that occurs without the intention or desire of the individual or couple[1,2]. This condition can have profound physical, mental, and social consequences for both the mother and the child[3]. Globally, unintended pregnancies remain a significant public health challenge, especially in low- and middle-income countries where access to family planning, education, and healthcare services may be limited[4]. The consequences of unintended pregnancies extend beyond immediate maternal and infant health risks, placing substantial burdens on healthcare systems, impeding progress toward sustainable development goals (SDGs), and perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality.

In the Asian region, approximately 19.1% of pregnancies are unintended, with a particularly high prevalence among young women under 20 years[5]. In Indonesia, the number of teenage pregnancies rose from 55000 in 2021 to 60000 in 2022, with many cases resulting from premarital pregnancies[6]. Unintended pregnancies often result in inadequate prenatal care, increasing the risk of complications such as preterm birth and low birth weight[7]. In addition, women experiencing unintended pregnancies frequently face heightened stress, anxiety, and depression, which further impacts both maternal and fetal health[8].

Previous research has primarily focused on the immediate outcomes of unintended pregnancy—such as maternal mental health issues and adverse birth outcomes[3,4,6-8] A growing body of evidence has also linked unintended pregnancies to neurodevelopmental problems in children, including higher risks of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and social-emotional difficulties[9-11]. However, most studies remain limited to isolated outcomes and early infancy, leaving a gap in understanding the broader and longer-term impacts during the critical early childhood years. In particular, little is known about how unintended pregnancy may influence both growth and developmental trajectories—such as undernutrition, stunting, abnormal head circumference, and delays in motor, cognitive, and emotional development—especially in low-resource settings.

To address this gap we conducted a multicenter, retrospective analysis of the long-term consequences of unintended pregnancy on early childhood growth and development across several Indonesian provinces. It was hypothesized that unintended pregnancy negatively affects both physical growth and developmental outcomes in children under 5 years of age. Through a robust methodological approach that integrated anthropometric indicators and developmental screening tools, this study aimed to generate evidence that can inform targeted public health policies and early childhood interventions both nationally and globally.

This study employed an analytical observational approach with a case-control design[12]. It was conducted across multiple research centers in Indonesia, specifically in the provinces of Central Java, Lampung, Bali, and West Nusa Tenggara. The study focused on children aged ≤ 5 years to examine early developmental risks associated with unintended pregnancy, as this period is critical for long-term cognitive and physical development.

Participants were divided into two groups: The case group (children aged ≤ 5 years born from unintended pregnancies) and the control group (children aged ≤ 5 years born from intended pregnancies). Classification was based on parental interviews using predetermined criteria, including maternal age at pregnancy, number of children, birth spacing, extramarital conception, and history of contraceptive failure[13]. Children diagnosed with Down syndrome, intellectual disability, hydrocephalus, brain tumors, or other congenital anomalies were excluded from the study. A total of 700 children were enrolled, comprising 350 in the case group and 350 in the control group, selected through multistage random sampling[14].

This study involved two types of variables: Manifest and latent. Manifest variables were directly measured through structured interviews, developmental assessments, and physical examinations. Latent variables—such as child growth and child development—were constructed from several related manifest variables and identified through statistical modeling. The manifest variables used to construct the latent variable child growth included the Height-for-Age Z-score (HAZ), Weight-for-Height Z-score (WHZ), BMI-for-Age Z-score (BAZ), and Head Circumference-for-Age Z-score (HCZ)[15].

For structural equation modeling analysis, all growth indicators were dichotomized. For HAZ, children categorized as ‘normal’ or ‘tall’ were coded as 0, while ‘stunted’ and ‘severely stunted’ were coded as 1. WHZ and BAZ were analyzed separately to reflect different aspects of nutritional status. For WHZ, children classified as ‘wasted’ or ‘severely wasted’ were coded as 1 and referred to as underweight. For BAZ, children classified as ‘underweight’ or ‘severely underweight’ were similarly coded as 1 and referred to as undernutrition, while all others—including those categorized as normal, overweight, or obese—were coded as 0. Although overweight and obesity are clinically important, they were not the primary focus of this study, which emphasized the impact of unintended pregnancy on undernutrition-related growth deficits. For HCZ, both macrocephaly and microcephaly were coded as 1 to indicate growth disorders, while normal head circumference was coded as 0.

The manifest variables that constructed the latent variable child development included motor and social skill development, hearing, vision, autism risk, emotional and behavioral functioning, and attention regulation. Motor and social skill development was assessed using the Indonesian Child Development Pre-screening Questionnaire[16] and categorized as either normal or having social communication and motor skill deficits. Hearing ability was measured using an age-appropriate hearing assessment tool[17], with results classified as normal or hearing impaired. Vision screening was conducted using the Visual Acuity Assessment Based on Age method[17,18], categorized as normal or having visual impairments. Autism risk was assessed using the Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-up[17,19], categorized as normal or indicative of ASD. Social-emotional and behavioral functioning was assessed with the Indonesian Child Emotional Problems Questionnaire[17,20], categorized as normal or presenting behavioral and emotional disorders. Lastly, attention regulation was measured using the Abbreviated Conners Rating Scale[17,21], categorized as normal or indicative of ADHD.

The research data were analyzed using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), a multivariate statistical technique that is well-suited for examining complex relationships among latent variables, particularly in exploratory research. The analysis was conducted using SmartPLS version 3.3.2[22]. Bootstrapping was performed with 5000 resamples to assess the statistical significance of path coefficients, providing robust estimates for hypothesis testing.

The evaluation of the model consisted of two key components: The measurement model (outer model) and the structural model (inner model). The measurement model was evaluated to ensure the reliability and validity of the constructs. Indicator reliability was assessed through outer loading values, with values above 0.50 considered acceptable in exploratory research. Internal consistency reliability was examined using Cronbach’s Alpha, while convergent validity was assessed via average variance extracted (AVE), where values exceeding 0.50 indicate sufficient convergence. Discriminant validity was confirmed using cross-loading analysis, ensuring that each indicator had a higher loading on its respective construct than on other constructs.

The structural model was evaluated by analyzing the path coefficients to determine the strength and direction of the hypothesized relationships between constructs. The coefficient of determination (R2) was used to assess the model’s explanatory power, representing the proportion of variance in the dependent constructs explained by the independent variable. Effect size (f2) was also examined to determine the magnitude of influence exerted by the exogenous construct, with classifications of small, medium, or large. Furthermore, predictive relevance (Q2) was assessed using the blindfolding procedure to evaluate the model’s ability to accurately reconstruct the observed data[22,23].

This study was approved by Universitas Muhammadiyah Purwokerto (KEPK/UMP/19/VI/2021). All participants' parents were informed about the purpose of the study, research procedures, and written consent was obtained. They were assured that their personal information would be kept confidential, with full protection of their privacy. Additionally, participants were informed that they could withdraw from the interview or study at any time.

Table 1 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics of the children based on pregnancy intention. Among the 700 children analyzed, the distribution of sex was relatively balanced, with a slightly higher proportion of males in the unintended pregnancy group. The prevalence of low birth weight (< 2500 g) was also higher among children from unintended pregnancies (7.4%) than those from intended pregnancies (4.6%). Children from unintended pregnancies showed a higher prevalence of undernutrition as reflected by greater rates of wasting/severe wasting and underweight/severely underweight based on both WHZ and BAZ. Children from unintended pregnancies also experienced more stunting (23.4% vs 21.1%) and microcephaly (35.4% vs 22.3%) compared with children from intended pregnancies.

| Characteristics | Intended (n = 350) | Unintended (n = 350) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 148 (42.3) | 166 (47.4) |

| Female | 202 (57.7) | 184 (52.6) |

| Birth weight | ||

| ≥ 2500 gr | 334 (95.4) | 324 (92.6) |

| < 2500 gr | 16 (4.6) | 26 (7.4) |

| Weight-for-length, Z-score | ||

| Obese (> +3 SD) | 15 (4.3) | 12 (3.4) |

| Overweight (> +2 SD) | 47 (13.4) | 35 (10.0) |

| Risk of overweight (> +1 SD) | 62 (17.7) | 71 (20.3) |

| Normal (> -2 to +1 SD) | 186 (53.2) | 118 (33.7) |

| Wasted (< -2 SD) | 28 (8.0) | 80 (22.9) |

| Severely wasted (< -3 SD) | 12 (3.4) | 34 (9.7) |

| BMI-for-age, Z-score | ||

| Obese (> +3 SD) | 19 (5.4) | 15 (4.3) |

| Overweight (> +2 SD) | 44 (12.6) | 35 (10.0) |

| Risk of overweight (> +1 SD) | 63 (18.0) | 74 (21.1) |

| Normal (> -2 to +1 SD) | 189 (54.0) | 124 (35.4) |

| Underweight (< -2 SD) | 24 (6.9) | 71 (20.3) |

| Severely underweight (< -3 SD) | 11 (3.1) | 31 (8.9) |

| Height-for-age, Z-score | ||

| Tall (> +2 SD) | 19 (5.4) | 12 (3.4) |

| Normal (-2 to +2 SD) | 251 (71.8) | 246 (70.3) |

| Stunted (< -2 SD) | 74 (21.1) | 82 (23.4) |

| Severely stunted (< -3 SD) | 6 (1.7) | 10 (2.9) |

| Head circumference-for-age, Z-score | ||

| Macrocephaly (> +2 SD) | 3 (0.9) | 5 (1.4) |

| Normal (-2 to +2 SD) | 269 (76.8) | 221 (63.2) |

| Microcephaly (> -2 SD) | 78 (22.3) | 124 (35.4) |

| Screening child social-emotional and behavioral | ||

| Normal | 336 (96.0) | 196 (56.0) |

| Behavioral and emotional disorders | 14 (4.0) | 154 (44.0) |

| Screening for autistic spectrum disorder | ||

| Normal | 299 (85.4) | 192 (54.9) |

| Autism spectrum disorder | 51 (14.6) | 158 (45.1) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | ||

| No | 334 (95.4) | 257 (73.4) |

| Yes | 16 (4.6) | 93 (26.6) |

| The interdependence of motor and social skill development | ||

| Normal | 286 (81.7) | 210 (60.0) |

| Social communication and motor skill deficits | 64 (18.3) | 140 (40.0) |

| Pediatric vision screening | ||

| Normal | 336 (96.0) | 289 (82.6) |

| Visual impairments | 14 (4.0) | 61 (17.4) |

| Hearing screening | ||

| Normal | 304 (86.9) | 288 (82.3) |

| Hearing impaired | 46 (13.1) | 62 (17.7) |

Children from unintended pregnancies demonstrated poorer developmental outcomes across multiple domains. Behavioral and emotional disorders (44.0% vs 4.0%), ASD (45.1% vs 14.6%), and ADHD (26.6% vs 4.6%) were more prevalent in this group compared with children from intended pregnancies. Deficits in social communication and motor skills (40.0% vs 18.3%) as well as higher rates of visual (17.4% vs 4.0%) and hearing impairments (17.7% vs 13.1%) were also observed.

Table 2 summarizes the results of the measurement and structural model evaluations. In the measurement model, outer loading values ranged from 0.504 to 0.855, indicating acceptable indicator reliability for exploratory research. Cronbach’s Alpha values (0.628-1.00) met the minimum threshold for internal consistency, while AVE values (0.689-1.00) confirmed good convergent validity. Discriminant validity was supported through cross-loadings, with each indicator loading higher on its intended construct than on others.

| Measurement | Results | Standard |

| Outer model | ||

| Outer loading | 0.504-0.855 | > 0.70 (ideal), > 0.50 acceptable for exploratory research |

| Cronbach’s alpha | 0.628-1.00 | > 0.60 (exploratory), > 0.70 (confirmatory) |

| AVE | 0.689-1.00 | > 0.50 |

| Cross-loadings | Loading on own construct > other constructs | Loading on own construct > other constructs |

| Inner model | ||

| Path coefficient | 0.276 (Child growth), 0.583 (Child development) | Values closer to 1 indicate stronger relationships |

| R2 | 0.176 (Child growth), 0.339 (Child development) | ≥ 0.67 (substantial), ≥ 0.33 (moderate) and ≥ 0.19 (weak) |

| f2 | 0.182 (Child growth), 0.514 (Child development) | ≥ 0.35 (large), ≥ 0.15 (medium) and ≥ 0.02 (small) |

| Q2 | 0.131 (Child growth), 0.187 (Child development) | > 0 |

For the structural model, path coefficients showed that unintended pregnancy had a moderate effect on child growth (β = 0.276) and a strong effect on child development (β = 0.584). The R2 values (0.176 for child growth and 0.339 for child development) indicate weak to moderate explanatory power. Effect sizes (f2 = 0.182 and 0.514) suggest moderate and large effects, respectively. Predictive relevance (Q2 = 0.131 for growth and 0.187 for development) confirms the model’s ability to predict the observed data.

Hypothesis testing showed that unintended pregnancy had a statistically significant impact on both child growth (t = 8.178; P < 0.001) and child development (t = 25.688; P < 0.001). Among the child growth indicators, the strongest effects were observed in underweight status (t = 27.302), undernutrition based on BMI-for-age (t = 26.199), abnormal head circumference (t = 4.197), and stunting/severe stunting (t = 2.334).

The most affected domains for child development were behavioral and emotional disorders (t = 27.722), ASD (t = 17.942), ADHD (t = 11.855), social communication and motor skill deficits (t = 6.409), visual impairments (t = 5.378), and hearing impairments (t = 3.002). All indicators were statistically significant (P < 0.01). These findings reflected the robust and multifaceted impact of unintended pregnancy on both physical and developmental outcomes in early childhood. The full structural model illustrating these relationships is presented in Figure 1.

Unintended pregnancy appears to be significantly associated with an increased risk of both physical and developmental impairments in early childhood. Children born from unintended pregnancies exhibited higher rates of undernutrition as reflected in the WHZ and BAZ scores alongside stunting and abnormal head circumference. These children demonstrated a greater prevalence of behavioral and emotional disorders, ASD, ADHD, and delays in motor and social development. These findings highlighted the physical, cognitive, and emotional vulnerabilities faced by children from unintended pregnancies.

The mechanisms underlying these associations are multifaceted. A key contributing factor was the inadequate prenatal care that is often associated with unintended pregnancies. Studies have shown that females with unintended pregnancies are significantly less likely to seek antenatal care[24], depriving them of critical services such as health monitoring, nutritional counseling, and early detection of complications. This lack of knowledge regarding essential nutrients leads to deficiencies that directly impair fetal development including reduced brain growth, low birth weight, and abnormal head circumference[25-28]. These findings emphasized the importance of ensuring that all pregnancies, regardless of intention, receive adequate prenatal support. This is also a priority strongly aligned with the sustainable development goals.

Maternal psychosocial stress is often elevated in cases of unintended pregnancy and may play a critical role in ex

The postnatal environment further compounds these risks. Unintended pregnancies have been linked to reduced maternal-infant bonding, higher incidence of postpartum distress, and lower rates of breastfeeding and immunization—all of which are essential for optimal early childhood development[34,35]. Children from these pregnancies may also face neglect or reduced parental investment, especially when born to mothers who are young, unmarried, or living in economic hardship. These conditions limit access to nutritious food, educational stimulation, and responsive caregiving—factors critical to a child’s physical, emotional, and cognitive development[26,36]. These findings underscore the im

A socioeconomic disadvantage further amplifies the developmental risks of unintended pregnancies. Many mothers in this study who experienced unintended pregnancies faced financial instability, which likely constrained their ability to access quality healthcare and nutrition. Economic hardship during both the prenatal and postnatal periods has been widely associated with poor growth outcomes, including stunting and undernutrition, as well as developmental delays[27,37,38]. These findings call for integrated public health strategies that go beyond clinical care and address the broader social determinants of health, particularly for women and children in low- and middle-income settings.

The design of this study was groundbreaking by involving diverse regions of Indonesia for multicenter, case-control research. By incorporating multiple regions with varying sociocultural contexts, the study provided robust, generalizable data on the impact of unintended pregnancy across different population groups. Furthermore, the use of PLS-SEM added a sophisticated analytical approach[22] to allow nuanced understanding of the relationships between unintended pregnancy and its various developmental outcomes. This level of statistical rigor ensured the reliability of the findings. Our observations have contributed significantly to the global body of research on child development and reproductive health.

While this study provides valuable insights, several limitations should be acknowledged. The retrospective design may introduce recall bias, particularly in how participants reported pregnancy intentions, potentially affecting data accuracy. Although the study controls for certain socio-economic factors, other crucial variables such as maternal mental health and access to healthcare services were not fully accounted for, which could influence child growth and development outcomes. Additionally, while the study offers important findings on early childhood growth and development, it does not assess long-term consequences beyond five years of age. Future longitudinal research is needed to evaluate how early-life disadvantages related to unintended pregnancy influence later academic achievement, social adaptation, and economic well-being.

Despite these limitations, this study presents robust empirical evidence on the lasting consequences of unintended pregnancy. The findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive strategies—ranging from improved access to family planning and quality prenatal care to enhanced postnatal support systems—to prevent intergenerational cycles of disadvantage and promote healthier child development trajectories.

This study provides strong evidence that unintended pregnancy has significant and multifaceted impacts on child growth and development. Children born from unintended pregnancies are more likely to experience undernutrition, abnormal head circumference, and stunting. Developmentally, they exhibit heightened risks of behavioral and emotional disorders, ASD, ADHD, as well as deficits in social communication, vision, and hearing. These findings highlight the urgent need to strengthen family planning services, ensure equitable access to prenatal and postnatal care, and address the socio-economic disparities that exacerbate these outcomes. Early identification and intervention are critical to mitigating developmental risks and improving long-term health trajectories. Future longitudinal studies should explore how these early-life disadvantages influence educational attainment, social functioning, and economic productivity in later life.

The author would like to thank the research team, the research subjects from where the researchers took the data, and the institutions that have funded this research activity.

| 1. | Kassahun EA, Zeleke LB, Dessie AA, Gersa BG, Oumer HI, Derseh HA, Arage MW, Azeze GG. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy among women attending antenatal care in Maichew Town, Northern Ethiopia, 2017. BMC Res Notes. 2019;12:381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Johnson-Mallard V, Kostas-Polston EA, Woods NF, Simmonds KE, Alexander IM, Taylor D. Unintended pregnancy: a framework for prevention and options for midlife women in the US. Womens Midlife Health. 2017;3:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kantorová V. Unintended pregnancy and abortion: what does it tell us about reproductive health and autonomy? Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e1106-e1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yazdkhasti M, Pourreza A, Pirak A, Abdi F. Unintended Pregnancy and Its Adverse Social and Economic Consequences on Health System: A Narrative Review Article. Iran J Public Health. 2015;44:12-21. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sarder A, Islam SMS, Maniruzzaman, Talukder A, Ahammed B. Prevalence of unintended pregnancy and its associated factors: Evidence from six south Asian countries. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yanti L, Supriyadi S, Santosa A. Unwanted pregnancy as a critical factor of stunting in Indonesia. medisians. 2023;21:1. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Hajizadeh M, Nghiem S. Does unwanted pregnancy lead to adverse health and healthcare utilization for mother and child? Evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:457-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Muskens L, Boekhorst MGBM, Kop WJ, van den Heuvel MI, Pop VJM, Beerthuizen A. The association of unplanned pregnancy with perinatal depression: a longitudinal cohort study. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2022;25:611-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | de La Rochebrochard E, Joshi H. Children born after unplanned pregnancies and cognitive development at 3 years: social differentials in the United Kingdom Millennium Cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:910-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Omani-Samani R, Ranjbaran M, Mohammadi M, Esmailzadeh A, Sepidarkish M, Maroufizadeh S, Almasi-Hashiani A. Impact of Unintended Pregnancy on Maternal and Neonatal Outcomes. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2019;69:136-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Solís-Cordero K, Couto LA, Duarte LS, Borges ALV, Fujimori E. Pregnancy planning does not interfere with child development in children aged from 11 to 23 months old. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2021;29:e3506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Setia MS. Methodology Series Module 2: Case-control Studies. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:146-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Supriyadi S, Yanti L. Factors analysis of unwanted pregnancies among women childbearing age in Indonesia: analysis of demographic and health survey data in 2017. medisians. 2020;18:93. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Elfil M, Negida A. Sampling methods in Clinical Research; an Educational Review. Emerg (Tehran). 2017;5:e52. [PubMed] |

| 15. | World Health Organization. WHO child growth standards: length/height-for-age, weight-for-age, weight-for-length, weight -for-height and body mass index-for-age: methods and development. Available from: https://www.who.int/tools/child-growth-standards/standards/p. |

| 16. | Simangunsong SW, Machfudz S, Sitaresmi MN. Accuracy of the Indonesian child development pre-screening questionnaire. PI. 2012;52:6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kementrian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. [Pedoman pelaksanaan stimulasi, deteksi, dan intervensi dini tumbuh kembang anak di tingkat pelayanan kesehatan dasar]. 2022nd ed. Jakarta: Kementrian Kesehatan Republik Indonesia. |

| 18. | Mahesh C, Ravi R, Satwinder S, Gaurav D, Pratik S, Shamit P, Nalin S. Assessment of pediatric visual acuity. Indian J Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2024;2024:22945. |

| 19. | Coelho-Medeiros ME, Bronstein J, Aedo K, Pereira JA, Arraño V, Perez CA, Valenzuela PM, Moore R, Garrido I, Bedregal P. M-CHAT-R/F Validation as a screening tool for early detection in children with autism spectrum disorder. Rev Chil Pediatr. 2019;90:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Setiawati Y, Juniar S. [Pedoman deteksi dini gangguan mental emosional masa kanak untuk petugas kesehatan puskesmas]. Surabaya: Dwi Putra Pustaka Jaya. |

| 21. | Izzo VA, Donati MA, Novello F, Maschietto D, Primi C. The Conners 3-short forms: Evaluating the adequacy of brief versions to assess ADHD symptoms and related problems. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24:791-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Garson GD. Partial least squares: regression and structural equation models. 2016th ed. Statistical Associates Publishing, 2016. |

| 23. | Subhaktiyasa PG. PLS-SEM for Multivariate Analysis: A Practical Guide to Educational Research using SmartPLS. Eduline J Educ Learn Innov. 2024;4:353-365. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Abame DE, Abera M, Tesfay A, Yohannes Y, Ermias D, Markos T, Goba G. Relationship Between Unintended Pregnancy and Antenatal Care Use During Pregnancy in Hadiya Zone, Southern Ethiopia. J Reprod Infertil. 2019;20:42-51. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Marshall NE, Abrams B, Barbour LA, Catalano P, Christian P, Friedman JE, Hay WW Jr, Hernandez TL, Krebs NF, Oken E, Purnell JQ, Roberts JM, Soltani H, Wallace J, Thornburg KL. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: lifelong consequences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;226:607-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 84.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Simermann M, Rothenburger S, Auburtin B, Hascoët JM. Outcome of children born after pregnancy denial. Arch Pediatr. 2018;25:219-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Eftekhariyazdi M, Mehrbakhsh M, Neamatshahi M, Moghadam MY. Comparison of pregnancy complications in unintended and intended pregnancy: A prospective follow-up study. Biomedicine (Taipei). 2021;11:51-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Price SM, Caughey AB. The impact of prenatal care on pregnancy outcomes in women with depression. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35:3948-3954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Dahlerup BR, Egsmose EL, Siersma V, Mortensen EL, Hedegaard M, Knudsen LE, Mathiesen L. Maternal stress and placental function, a study using questionnaires and biomarkers at birth. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0207184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wadhwa PD, Entringer S, Buss C, Lu MC. The contribution of maternal stress to preterm birth: issues and considerations. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:351-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jang M, Molino AR, Ribeiro MV, Mariano M, Martins SS, Caetano SC, Surkan PJ. Maternal Pregnancy Intention and Developmental Outcomes in Brazilian Preschool-Aged Children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2021;42:e15-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Herring S, Gray K, Taffe J, Tonge B, Sweeney D, Einfeld S. Behaviour and emotional problems in toddlers with pervasive developmental disorders and developmental delay: associations with parental mental health and family functioning. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2006;50:874-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jagtap A, Jagtap B, Jagtap R, Lamture Y, Gomase K. Effects of Prenatal Stress on Behavior, Cognition, and Psychopathology: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e47044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lindberg L, Maddow-Zimet I, Kost K, Lincoln A. Pregnancy intentions and maternal and child health: an analysis of longitudinal data in Oklahoma. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1087-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Aranti WA. Associations between Unplanned Pregnancy, Low Social Support, Domestic Violence, and Intrapartum Complication, with Postpartum Depression: Meta Analysis. J Matern Child Health. 2024;9:169-185. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Baschieri A, Machiyama K, Floyd S, Dube A, Molesworth A, Chihana M, Glynn JR, Crampin AC, French N, Cleland J. Unintended Childbearing and Child Growth in Northern Malawi. Matern Child Health J. 2017;21:467-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Gharaee M, Baradaran HR. Consequences of unintended pregnancy on mother and fetus and newborn in North-East of Iran. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33:876-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Mohamed EAB, Hamed AF, Yousef FMA, Ahmed EA. Prevalence, determinants, and outcomes of unintended pregnancy in Sohag district, Egypt. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2019;94:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/