Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113659

Revised: September 22, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 157 Days and 3.7 Hours

Intertrochanteric or pertrochanteric fractures are common among the elderly population. They are primarily treated by internal fixation. Malunion, delayed union, and implant-related complications are often seen in this population due to osteoporosis, which leads to inadequate bone stock and delayed healing of bone. Teriparatide is an established first-line anabolic treatment for osteoporosis that increases bone turnover and promotes new bone formation. Recent papers have shown its role in fracture union in which it enhanced the callus formation and bridged the fractured ends of the bones.

To determine the effect of subcutaneous injection of teriparatide on osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures.

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library for English language articles that were published by June 3, 2025. We selected articles that compared the use of teriparatide injection with either no injection or placebo in patients with osteoporosis who experienced an intertrochanteric fracture that was treated with internal fixation. Relevant data, including union time (primary out

Six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two non-randomized studies) met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review. A total of 393 patients [teriparatide (n = 175) and control (n = 218)] were included in the studies. Data from five of these studies were combined, and the pooled meta-analysis of the fracture union time [teriparatide (n = 155) and control (n = 198)] showed a significant difference in favor of the teriparatide group (standardized mean difference = -0.77, 95% confidence interval: -0.99 to -0.55, P < 0.00001). Other radiological parameters like varus collapse and incidence of complications were decreased in the teriparatide group. Functional outcomes were better in the early follow-up of patients who received teriparatide. However, the follow-up outcomes were similar in the long term for both groups.

The meta-analysis showed that teriparatide reduced union time, varus collapse, and complications in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures. However, these findings should be interpreted cautiously due to limited evidence and small sample size.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis was conducted to determine the effect of subcutaneous injection of teriparatide on the bone union of osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures. Six studies (four randomized controlled trials and two non-randomized studies) met the inclusion criteria for systematic review. We found in the pooled meta-analysis that teriparatide reduced union time, varus collapse, and complications in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures. Future studies including more patients should be undertaken to confirm the results of this meta-analysis.

- Citation: Keshav K, Kaustubh K, Mishra P. Effect of teriparatide on improving fracture union in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 113659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/113659.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113659

Intertrochanteric or pertrochanteric fractures are one of the most common fractures among the elderly population. They are primarily managed by internal fixation unless there are contraindications for surgery. Simple fractures are often managed by dynamic hip screw (DHS) while unstable fractures (4-part, posteromedial comminution, absent lateral wall, reverse oblique, and those with subtrochanteric extension) are managed with proximal femoral nails [proximal femoral nail (PFN), PFN-a, PFN-A2, Trigen, etc.][1,2]. Malunion, delayed union, and implant-related complications are often seen in this elderly population due to osteoporosis, which leads to inadequate bone stock and delayed bone healing. Despite the advancements in implant designs, the complications have remained constant due to not addressing the biology of the bone stock and union capacity[2-5].

Osteoporosis can be effectively treated with bisphosphonates. However, they prevent bone turnover and are contraindicated in fresh fractures. Teriparatide is an anabolic treatment for osteoporosis that increases bone turnover and leads to the formation of new bone. Teriparatide injection has already been established as the first-line anabolic modality of treatment[6-10]. Recent studies have demonstrated the role of teriparatide in fracture union in which it enhanced the callus formation and bridged the fractured ends of the bones[11,12]. However, the effect of teriparatide on intertrochanteric fractures is unknown.

We conducted a systematic review of the available literature to determine the effect of teriparatide injection on surgically fixed intertrochanteric fractures. We included studies comparing teriparatide injection with no injection or placebo. The purpose of this study was to determine the effect of teriparatide on radiological (union rate, union time, varus collapse, etc.) and clinical (functional scores like Harris Hip Score, Visual Analogue Scale, complications, etc.) parameters.

The protocol of this systematic review and meta-analysis was registered on the PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (No. CRD42024502631) on January 28, 2024[13]. The study was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[14]. Two reviewers (Keshav K and Kaustubh K) searched the online databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) from inception up to June 3, 2025. Only the papers published in English language were included. The search strategy used for each medical database is presented in Table 1 and involved a combination of keywords and Medical Subject Headings terms related to teriparatide, intertrochanteric fractures, and osteoporosis.

| Database | Search strategy | Publications identified, n |

| PubMed | [“teriparatid*“(All Fields) OR “teriparatid“(All Fields) OR “teriparatide“(MeSH Terms) OR “teriparatide“(All Fields) OR “forteo”(All Fields) OR “teriparatide”(MeSH Terms)] AND [“fracture*”(All Fields] OR “fractures, bone” (MeSH Terms]) AND [“trochanter*” (All Fields) OR “intertrochanteric”(All Fields) OR “pertrochanteral”(All Fields) OR “pertrochanteric”(All Fields) OR “hip”(MeSH Terms) OR “hip”(All Fields)] AND [“osteoporo*”(All Fields) OR “osteoporosis, postmenopausal”(MeSH Terms) OR “osteoporosis”(MeSH Terms)] | 479 |

| EMBASE | ((teriparatid* or forteo) and fracture* and (trochanter* or intertrochanteric or pertrochanteric or hip) and osteoporo*).mp. | 1368 |

| Scopus | Article title, Abstract, Keyword (teriparatid* OR forteo) AND fracture* AND (trochanter* OR intertrochanteric OR pertrochanteric OR hip) AND osteoporo* | 758 |

| Cochrane | ((teriparatid* or forteo) and fracture* and (trochanter* or intertrochanteric or pertrochanteric or hip) and osteoporo*):ti,ab,kw | 235 |

All comparative studies [randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized clinical trials, and observational studies] published in English in which teriparatide injection was compared with no injection or placebo in patients with osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures (defined radiologically as per standard Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Osteosynthesefragen/Orthopedic Trauma Association classification systems), who were managed by internal fixation were eligible for inclusion. Although the preferred inclusion criterion was confirmed diagnosis of osteoporosis based on T-score < -2.5, studies that had enrolled typical geriatric patients (> 50 years age, suggestive of osteoporosis regardless of explicit T-score) were considered eligible. Studies involving atypical femoral fractures, old non-union fractures and secondary osteoporosis were excluded from the review. Pilot studies and studies with no data related to the primary outcome of interest were also excluded.

All studies extracted from the online databases and other sources were compiled as a single Excel file and screened by both reviewers (Keshav K and Kaustubh K) to identify any duplications based on study titles, abstracts, and publication details like author, publication year, journal name, etc. The titles and abstracts of the remaining studies were screened for inclusion and exclusion. The full texts of potentially eligible studies were evaluated independently by both reviewers (Keshav K and Kaustubh K), and a list of eligible studies was created. Any disagreements regarding study eligibility were resolved through discussion between the reviewers and if needed with the third reviewer (Mishra P).

Two authors (Keshav K and Kaustubh K) working independently extracted the following information from all articles: Author; year of publication; country; type of study; number of patients in both groups; age; sex; bone mineral density (BMD); presence of comorbidities; fracture type; method of surgical fracture fixation; length of hospital stay; and duration of surgery. Information was recorded about the dose, route, and duration of administration of the teriparatide injection in the intervention group and the modality used in the control group (i.e., placebo or non-administration of teriparatide injection). The radiological outcome data (e.g., union rate, union time, varus collapse), functional outcome scores (e.g., Harris Hip Score, Visual Analogue Scale, Lower Extremity Functional Scale, etc.), and incidence of complications (e.g., non-union, malunion, infection, reoperation rate, etc.) were also extracted from the selected studies (Table 2)[15,16].

| Ref. | Country | Type of study | Patients, n | Other patient parameters | Follow-up duration | Teriparatide injection parameters: Dose, route, and duration of administration | Control modality parameters: Dose, route, and duration of administration | |||

| Teriparatide group | Control group | Teriparatide group | Control group | Teriparatide group | Control group | |||||

| Huang et al[21] | Taiwan | Retrospective | 47 | 83 | BMD: -4.2 ± 1.3 | BMD: -3.9 ± 1.2 | Minimum of 12 months | Minimum of 12 months | 20 μg/day subcutaneously usually for 18 months (minimum of 12 months) beginning on the day of surgery | None |

| Kim et al[22] | South Korea | Retrospective | 52 | 60 | BMD: -3.4 | BMD: -3.2 (-5.2 to | Minimum follow-up was 10 months (average: 1.6 years; range: 0.8-3.0 years) | Minimum follow-up was 10 months (average: 1.6 years; range: 0.8-3.0 years) | 20 μg/day subcutaneously for 2 months | None |

| Rana et al[23] | India | RCT | 15 | 15 | BMD (kg/m2): 0.537 ± 0.073 | BMD (kg/m2): 0.561 ± 0.081 | 6 months | 6 months | 20 μg/day subcutaneously for 6 months | None |

| Mishra et al[24] | India | RCT | 16 | 15 | BMD of all patients < | BMD of all patients < -2.5 | 24 weeks | 24 weeks | 20 μg/day subcutaneously for 24 weeks | None |

| Aggarwal et al[26] | India | RCT | 20 | 20 | BMD: -3.04 ± 0.43 | BMD: | 6 months (24 weeks) | 6 months (24 weeks) | 20 μg/day subcutaneously for 24 weeks | None |

| Tanavalee et al[25] | Thailand | RCT | 25 | 25 | BMD (g/cm3): Total hip: 0.631 ± 0.211; femoral neck: 0.518 ± 0.156 | BMD (g/cm3): Total hip: 0.598 ± 0.220; femoral neck: 0.517 ± 0.201 | 24 weeks | 24 weeks | 20 μg/day subcutaneously for 24 weeks | Normal saline |

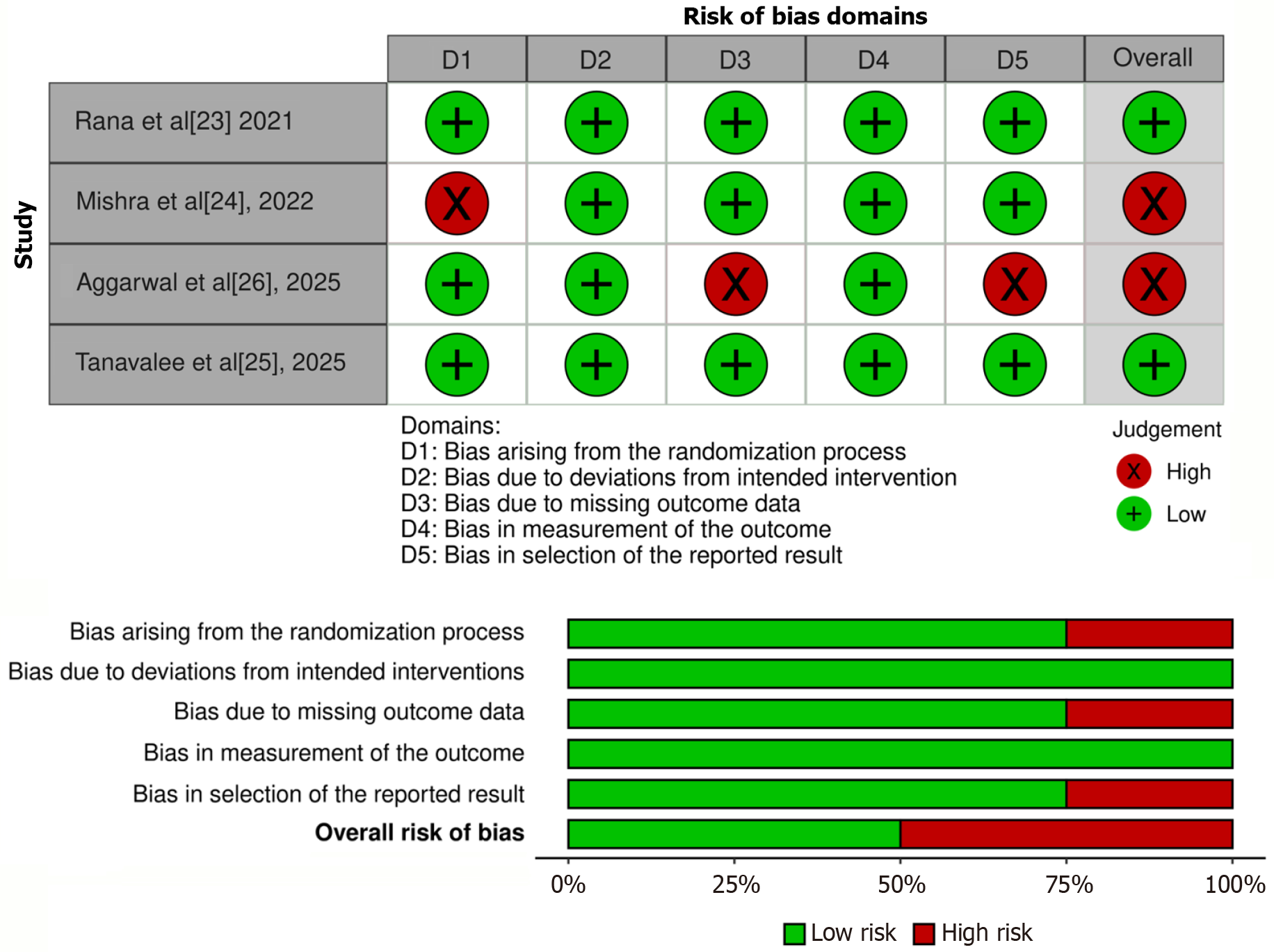

Two reviewers (Keshav K and Kaustubh K) assessed the quality of the included studies to find potential bias. Risk of bias of RCTs was assessed by the Cochrane Risk of Bias assessment tool 2[17]. For nonrandomized studies the methodological index for nonrandomized studies tool was used[18]. The online Robvis tool was used to create risk-of-bias plots for RCTs included in our study[19].

All comparative studies were used for the qualitative data synthesis. The data across studies that could be combined were used for quantitative synthesis. For those studies that mentioned dichotomous variables at multiple time points, we used established statistical methods to convert the data into estimated mean ± SD, in line with the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Review of Interventions and allowing for inclusion of dichotomous data alongside continuous outcome data[20]. The subscription-based web version of Cochrane’s Review Manager (Cochrane Collaboration, United Kingdom) was used for the meta-analysis. The data synthesized were risk ratios/odds ratios for dichotomous variables and mean difference/standardized mean difference (SMD) for continuous/discrete variables. In the case of cross-study variation in outcomes scale or time points, the SMD was used, allowing for transparent and unbiased pooling of results with heterogenous effect measures. Heterogeneity between studies in effect measures was assessed using the I2 statistic, and a fixed or random effect model was adopted to pool the results. Random-effects models were employed when statistical heterogeneity was considerable (P-value < 0.10 or I2 > 50%); fixed-effects models were employed in other cases.

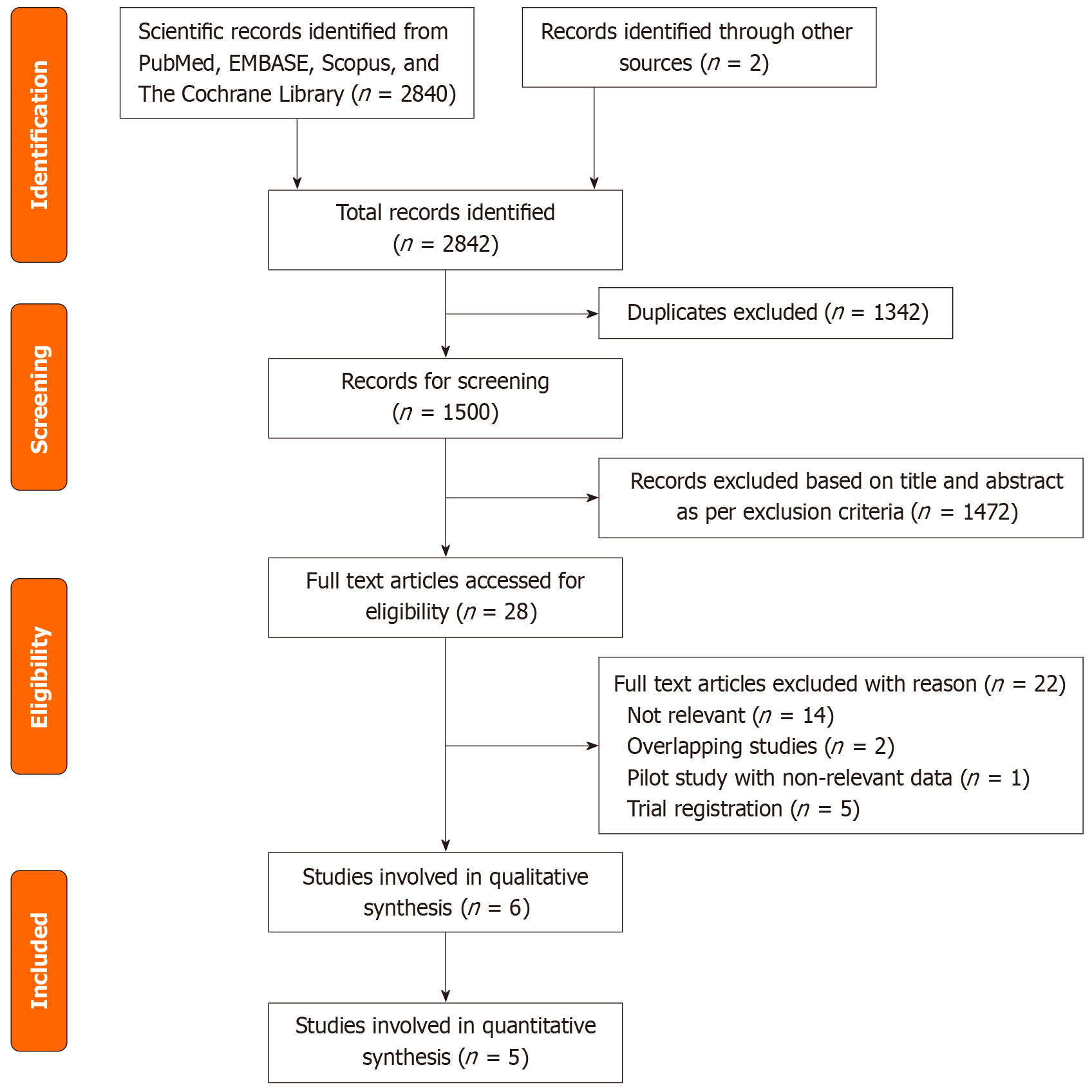

Table 1 shows the search strategy and number of results from the four databases. A total of 2842 records were identified. There were 1342 duplications yielding 1500 records after duplication removal. These articles were assessed by title and abstract, leaving 28 articles for full-text screening. Among them 14 were not relevant and 5 were trial registrations. Therefore, 9 articles were included[21-29]. However, two previous publications[27,28] appeared to be partially overlapping studies (overlapping cohorts) of subsequently published studies, respectively[21,22]. We e-mailed the corresponding authors of these publications but did not receive a reply. Therefore, we only included the studies that were published more recently to avoid duplication of the patient population and their data[21,22]. Another study was a feasibility pilot study for an RCT and was excluded[29]. Six studies met our inclusion and exclusion criteria and were included for systematic review[21-26]. One study did not include the union time nor the number of patients with fractures that united at various time points. No data that could be combined with the other studies was available and thus was not included in the meta-analysis (Figure 1)[26].

The studies included in our studies were published between 2016 and 2025. Three of these studies were from India[23,24,26], one from Taiwan[21], one from South Korea[22], and one from Malaysia[25]. The studies from India and Malaysia were RCTs while the other two were retrospective observational studies. Table 2 includes the publication data, major demographic and preoperative characteristics of the study participants, and the duration of follow-up for each study. A total of 393 patients [teriparatide (n = 175) and control (n = 218)] were evaluated in our systematic review. For our meta-analysis there were 353 total patients [teriparatide (n = 155) and control (n = 198)]. The number of patients in the individual studies ranged from 30 to 130. Table 3 summarizes the intraoperative, postoperative, and follow-up data extracted from the studies.

| Ref. | Radiological outcome data | Functional outcome data | Complications | BMD | ||||

| Teriparatide group | Control group | Teriparatide group | Control group | Teriparatide group | Control group | Teriparatide group | Control group | |

| Huang et al[21] | Union time (weeks): 12.3 ± 1.3; tip apex distance (mm): 22.0 ± 2.0; sliding of lag screw (mm): 3.0 ± 1.0; femoral shortening (mm): 2.0 ± 1.0; varus collapse (degrees): 2.0 ± 1.0 | Union time (weeks): 13.6 ± 1.5; tip apex distance (mm): 21.0 ± 2.0; sliding of lag screw (mm): 6.0 ± 2.0; femoral shortening (mm): 8.0 ± 6.0; varus collapse (degrees): 5.0 ± 2.0 | SF-12 Physical Component Survey Score; preinjury: 46 ± 9; 3 months: 28 ± 11; 6 months: 37 ± 11; 9 months: 39 ± 11; 12 months: 44 ± 12. SF-12 Mental Component Survey Score; preinjury: 59 ± 12; 3 months: 51 ± 11; 6 months: 54 ± 9; 9 months: 52 ± 11; 12 months: 54 ± 12 | SF-12 Physical Component Survey Score; preinjury: 46 ± 8; 3 months: 19 ± 8; 6 months: 28 ± 10; 9 months: 35 ± 10; 12 months: 41 ± 11. SF-12 Mental Component Survey Score; preinjury: 58 ± 13; 3 months: 51 ± 11; 6 months: 53 ± 10; 9 months: 53 ± 11; 12 months: 53 ± 11 | Overall complications: 12 (26%); superficial wound infection: 3 (6%); deep wound infection: 0; pneumonia: 4 (9%); urinary tract infection: 4 (9%); delayed union: 0; nonunion: 0; cutting of the lag screw: 1 (2%); implant failure: 0; mortality (not related to fracture): 2 (4%) | Overall complications: 47 (57%); superficial wound infection: 6 (7%); deep wound infection: 0; pneumonia: 13 (16%); urinary tract infection: 17 (20%); delayed union: 0; nonunion: 0; cutting of the lag screw: 11 (13%); implant failure: 0; mortality (not related to fracture): 16 (19%) | Not assessed in follow-up | Not assessed in follow-up |

| Kim et al[22] | Union rate by: 4 weeks 7%; 8 weeks 57%; 12 weeks 96%; 16 weeks 100%; 20 weeks 100%; 24 weeks 100% | Union rate by: 4 weeks 6%; 8 weeks 41%; 12 weeks 78%; 16 weeks 88%; 20 weeks 98%; 24 weeks 100% | Harris Hip Score after: 2 months 60.5 (10-80); 4 months 65.4 (20-90); 6 months 70.4 (24-90). VAS Pain Score after: 2 months 35.2 (10-80); 4 months 28.4 (5-70); 6 months 21.2 (5-70). VAS Stiffness Score after: 2 months 40.8 (20-90); 4 months 35.9 (10-80); 6 months 30.2 (10-80) | Harris Hip Score after: 2 months 645.2 (10-80); 4 months 55.4 (20-86); 6 months 60.4 (20-86). VAS Pain Score after: 2 months 52.4 (10-90); 4 months 41.5 (10-80); 6 months 32.8 (10-80). VAS Stiffness Score after: 2 months 50.6 (20-90); 4 months 44.8 (10-90); 6 months 32.8 (10-80) | Overall complications: 6 (11%); superficial wound infection: 1; deep wound infection: 0; pneumonia: 0; urinary tract infection: 0; mortality: 0; delayed union: 0; nonunion: 0; malunion: 3; superior cutting of the lag screw: 1; implant failure: 0; lateral screw migration requiring further intervention: 1; varus collapse with screw sliding: 0; avascular necrosis: 0 | Overall complications: 17 (28%); superficial wound infection: 2; deep wound infection: 1; pneumonia: 0; urinary tract infection: 0; mortality: 0; delayed union: 0; nonunion: 0; malunion: 8; superior cutting of the lag screw: 2; implant failure: 0; lateral screw migration requiring further intervention: 2; varus collapse with screw sliding: 2; avascular necrosis: 0 | Not assessed in follow-up | Not assessed in follow-up |

| Rana et al[23] | Union time (weeks): 13.33 ± 1.95; migration of helical blade (mm): 3 months 0.82 ± 0.73; 6 months 1.39 ± 1.21; change in neck-shaft angle (degrees) (varus collapse) by: 3 months 1.79 ± 0.72; 6 months 3.04 ± 1.46; femoral shortening (mm) by: 3 months 3.61 ± 2.91; 6 months 5.29 ± 4.10 | Union time (weeks): 15.47 ± 1.41; migration of helical blade (mm): 3 months 0.92 ± 0.84; 6 months 1.74 ± 0.82; change in neck-shaft angle (degrees) (varus collapse) by: 3 months 2.14 ± 1.01; 6 months 4.59 ± 2.03; femoral shortening (mm) by: 3 months 3.86 ± 3.12; 6 months 6.04 ± 4.31 | Percentage depreciation from Lower Extremity Functional Scale at: 3 months 32.17 ± 1.20; 6 months 24.83 ± 1.24 | Percentage depreciation from Lower Extremity Functional Scale at: 3 months 32.83 ± 1.00; 6 months 26.17 ± 1.1 | Overall complications: 1 (7%); bed sore: 1; malunion, non-union, or any implant related complications: 0 | Overall complications: 1 (6%); bed sore: 1; malunion, non-union, or any implant related complications: 0 | Percentage change in hip BMD at 6 months 1.81 ± 1.39% | Percentage change in hip BMD at 6 months 0.97 ± 1.14 % |

| Mishra et al[24] | Union rate by: 6 weeks 0; 12 weeks 56.25%; 24 weeks 100%. RUSH Score by: 6 weeks 22.20 ± 2.30; 12 weeks 28.6 ± 1.25; 24 weeks 30.0 ± 0.00. Tip-apex distance (mm) (measure of blade migration) by: 6 weeks 26.27 ± 5.87; 12 weeks 25.74 ± 3.35; 24 weeks 24.26 ± 1.92. Change in neck-shaft angle (degrees) (varus collapse) by: 6 weeks 0.24 ± 0.76; 12 weeks 1.91 ± 1.57; 24 weeks 2.86 ± 1.36. Femoral neck shortening (mm) by: 6 weeks 0.09 ± 0.06; 12 weeks 3.22 ± 1.91; 24 weeks 5.13 ± 2.41 | Union rate by: 6 weeks 0; 12 weeks 13.33%; 24 weeks 100%. RUSH Score by: 6 weeks 21.53 ± 2.83; 12 weeks 28.03 ± 1.55; 24 weeks 30.0 ± 0.00. Tip-apex distance (mm) (measure of blade migration) by: 6 weeks 25.8 ± 3.36; 12 weeks 23.96 ± 5.41; 24 weeks 22.57 ± 1.33. Change in neck-shaft angle (degrees) (varus collapse) by: 6 weeks 0.62 ± 1.03; 12 weeks 3.52 ± 1.24; 24 weeks 4.94 ± 1.90. Femoral neck shortening (mm) by: 6 weeks 0.15 ± 0.72; 12 weeks 3.72 ± 2.10; 24 weeks 7.02 ± 3.43 | Palmer and Parker Score by: 6 weeks 2.60 ± 1.25; 12 weeks 6.86 ± 1.26; 24 weeks 8.86 ± 0.12 | Palmer and Parker Score by: 6 weeks 2.46 ± 1.12; 12 weeks 6.53 ± 1.12; 24 weeks 8.6 ± 0.17 | Overall complications: 2 (13%); bed sore: 2; malunion, non-union, or any implant related complications: 0 | Overall complications: 1 (6%); bed sore: 1; malunion, non-union, or any implant related complications: 0 | T-score at: 6 weeks -3.4 ± 0.12; 12 weeks -3.31 ± 0.46; 24 weeks -3.29 ± 0.53 | T-score at: 6 weeks -3.36 ± 0.02; 12 weeks -3.02 ± 0.04; 24 weeks -2.86 ± 0.26 |

| Aggarwal et al[26] | 50% of the patients achieved union within 8-12 weeks. RUSH Score at: 6 weeks 22.52 ± 2.31; 12 weeks 28.62 ± 1.64; 24 weeks 29.95 ± 0.22 | 15% of the patients achieved union within 8-12 weeks. RUSH Score at: 6 weeks 22.10 ± 2.87; 12 weeks 27.65 ± 1.47; 24 weeks 29.88 ± 0.33 | NA | NA | NA | NA | T-score at 24 weeks -2.83 ± 0.43 | T-score at 24 weeks -3.15 ± 0.73 |

| Tanavalee et al[25] | Union time (weeks): 7.44 ± 3.34. Average RUSH Score at the time of fracture union: 24.4 points (range: 22.0-26.4 points) | Union time (weeks): 10.56 ± 4.98. Average RUSH Score at the time of fracture union: 23.2 points (range: 22.0-25.6 points) | Harris Hip Score at: 2 weeks 45.4 ± 14.7; 4 weeks 56.0 ± 15.5; 6 weeks 65.8 ± 14.0; 12 weeks 69.8 ± 17.6; 24 weeks 74.9 ± 17.8. TUGT (s) at: 4 weeks 66.6 ± 16.2; 6 weeks 44.0 ± 12.9; 12 weeks 36.7 ± 13.6; 24 weeks 28.7 ± 11.7. 5 × SST at: 4 weeks 48.6 ± 14.3; 6 weeks 44.0 ± 12.9; 12 weeks 36.7 ± 13.6; 24 weeks 28.0 ± 12.0 | Harris Hip Score at: 2 weeks 51.3 ± 13.6; 4 weeks 61.7 ± 14.1; 6 weeks 63.9 ± 14.3; 12 weeks 68.6 ± 19.4; 24 weeks 75.0 ± 16.7. TUGT (s) at: 4 weeks 73.3 ± 21.8; 6 weeks 42.9 ± 20.2; 12 weeks 36.9 ± 18.7; 24 weeks 36.4 ± 15.7. 5 × SST at: 4 weeks 57.6 ± 20.6; 6 weeks 42.9 ± 20.2; 12 weeks 38.8 ± 18.5; 24 weeks 36.4 ± 15.7 | Fixation failure: 0; nonunion: 0; injection-related issues: 1 (bruise around the injection site at 2nd-week visit) | Fixation failure: 0; nonunion: 0; injection-related issues: 1 (skin itching around the injection area) | BMD at 24 weeks (g/cm3): Total hip 0.607 ± 0.168; femoral neck: 0.505 ± 0.140 | BMD at 24 weeks (g/cm3): Total hip: 0.560 ± 0.168; femoral neck: 0.475 ± 0.138 |

Out of the six studies, two were high-quality RCTs (level of evidence: I)[23,25]. The other two RCTs had a high risk of bias (level of evidence: II). In one study the allocation to groups was based on the willingness of the study participants and not in a randomized manner[24]. In the other study the bias occurred in the missing outcome data and the reporting of the results (Figure 2)[26]. The other two studies were retrospective level III studies (Table 2)[21,22], in which the methodological index for non-randomized studies was used[18]. These studies scored 23 and 18, respectively[21,22]. While almost all the parameters in the study by Huang et al[21] were found to be adequately reported, the study by Kim et al[22] involved numerous parameters that were either not reported or reported inadequately (e.g., inclusion of consecutive patients, prospective calculation of study size, and prospective collection of data; Table 4).

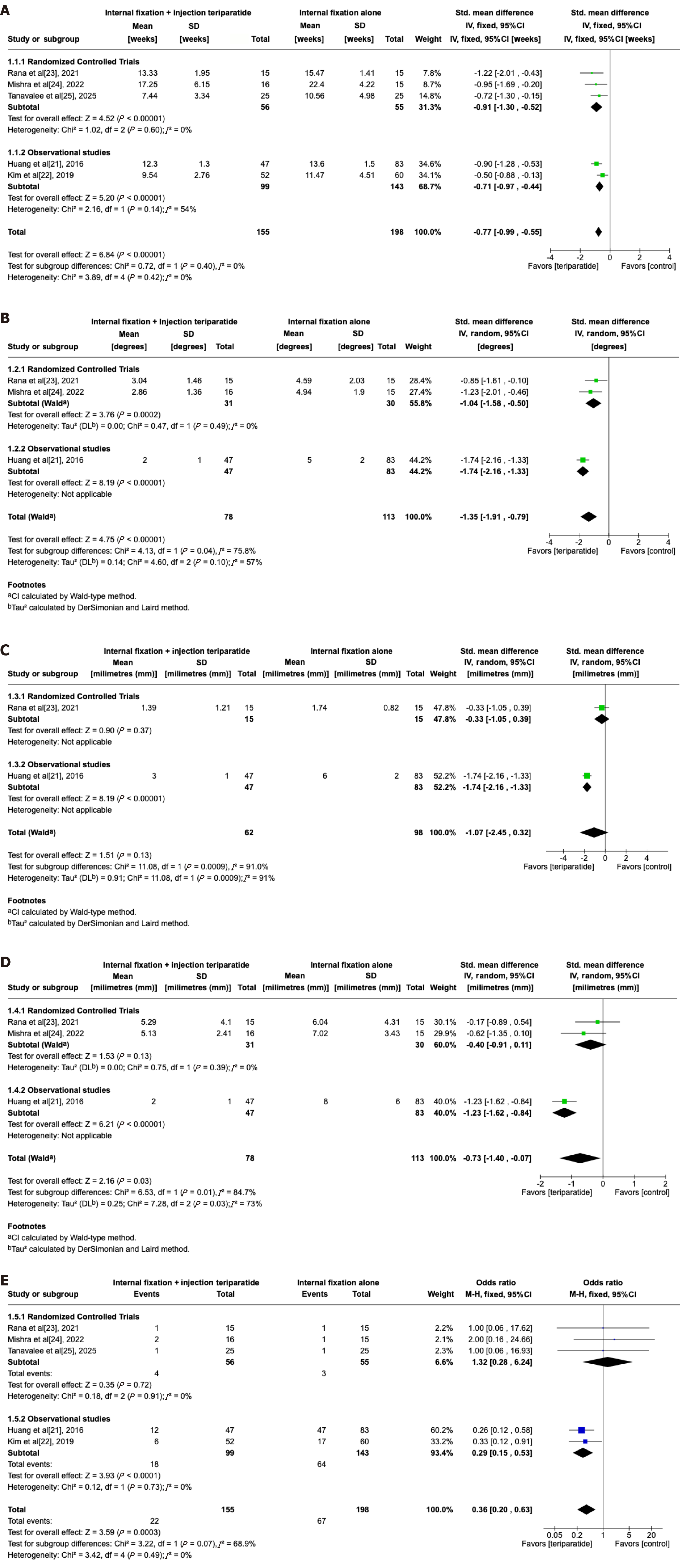

Two of the studies assessed union by only one parameter: Time to union[21,25]. Rana et al[23] included the union time and the number of patients with fracture union at various time points like 6 weeks, 10 weeks, etc. The other studies included only the number of patients with fracture union at specific weeks of follow-up[22,24]. However, the time points were different among the studies. To compare the data from the four studies, we converted the ‘union rate at different time points’ into the ‘mean union time with standard deviation’ from the data given in the individual studies (Table 3). The pooled analysis of the union times across these studies showed a significant difference with better union times in the teriparatide group [SMD = -0.77; 95% confidence interval (CI): -0.99 to -0.55; P < 0.00001; I2 = 0%; P = 0.42); Figure 3A].

Other radiological parameters: The other radiological parameters included varus collapse, sliding of the lag screw/helical blade, and femoral neck length shortening. Three studies included change in the neck shaft angle (varus collapse) in terms of degrees[21,23,24], while Kim et al[22] included varus collapse as a dichotomous variable (yes/no). After combining the data from the three studies, there was a higher degree of collapse (decrease in neck-shaft angle) in the control group than in the teriparatide group (SMD = -1.35; 95%CI: -1.91 to -0.79; P < 0.00001; I2 = 57%; P = 0.10; Figure 3B). Kim et al[22] found a varus collapse in 2 patients in the control group and 0 patients in the teriparatide group. Lateral screw migration was mentioned in only two studies (DHS in Huang et al[21] and helical blade in Rana et al[23]). Although migration was lower in the teriparatide group, the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.13; Figure 3C). Femoral neck length shortening was statistically different in the two groups (P = 0.03). This parameter was included in three studies (SMD = -0.73; 95%CI: -1.40 to -0.07; P = 0.03; I2 = 73%; P = 0.03; Figure 3D).

Functional outcome: Kim et al[22] and Tanavalee et al[25] used the Harris Hip Score, and the other studies used different functional outcome measures. Mishra et al[24] used the Palmer and Parker Scale, Rana et al[23] used percentage depreciation from the Lower Extremity Functional Scale, and Huang et al[21] used the 12-item short form survey. The time points when functional outcome scoring was conducted were different in each study. However, at all time points in the initial follow-up across the individual studies, the scores were better in the teriparatide group than in the control group. However, the outcome scores reached similar levels in both groups at long-term time points (e.g., 6 months and beyond; Table 3).

Complications: There was much variation in the reporting of complications in the studies. However, the total number of complications showed a decrease over the years. Earlier studies from Huang et al[21] and Kim et al[22] had a higher incidence of complications compared with studies conducted more recently. Infection (superficial or deep), pneumonia, are urinary tract infection were frequently reported. Local complications such as cut through of lag screws, lateral screw migration requiring revision surgery, malunion, etc., occurred more frequently in the control group. The odds ratio of the total number of complications was lower in the teriparatide group (odds ratio = 0.36; 95%CI: 0.20-0.63; P = 0.0003; I2 = 0%; P = 0.49; Figure 3E).

Change in BMD: BMD was not assessed in the follow-up period in the two retrospective studies[21,22]. Rana et al[23] included the percentage change of BMD at 6 months and observed that it was higher in the teriparatide group. A similar trend was observed by Mishra et al[24]; they measured BMD of the hip bone at 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks and found an improvement in the T-scores in both groups following fracture fixation. Tanavalee et al[25] and Aggarwal et al[26] measured BMD at 24 weeks and found an increase in the teriparatide group compared with the control group. While Tanavalee et al[25] reported the values as g/cm3, Aggarwal et al[26] used T-scores.

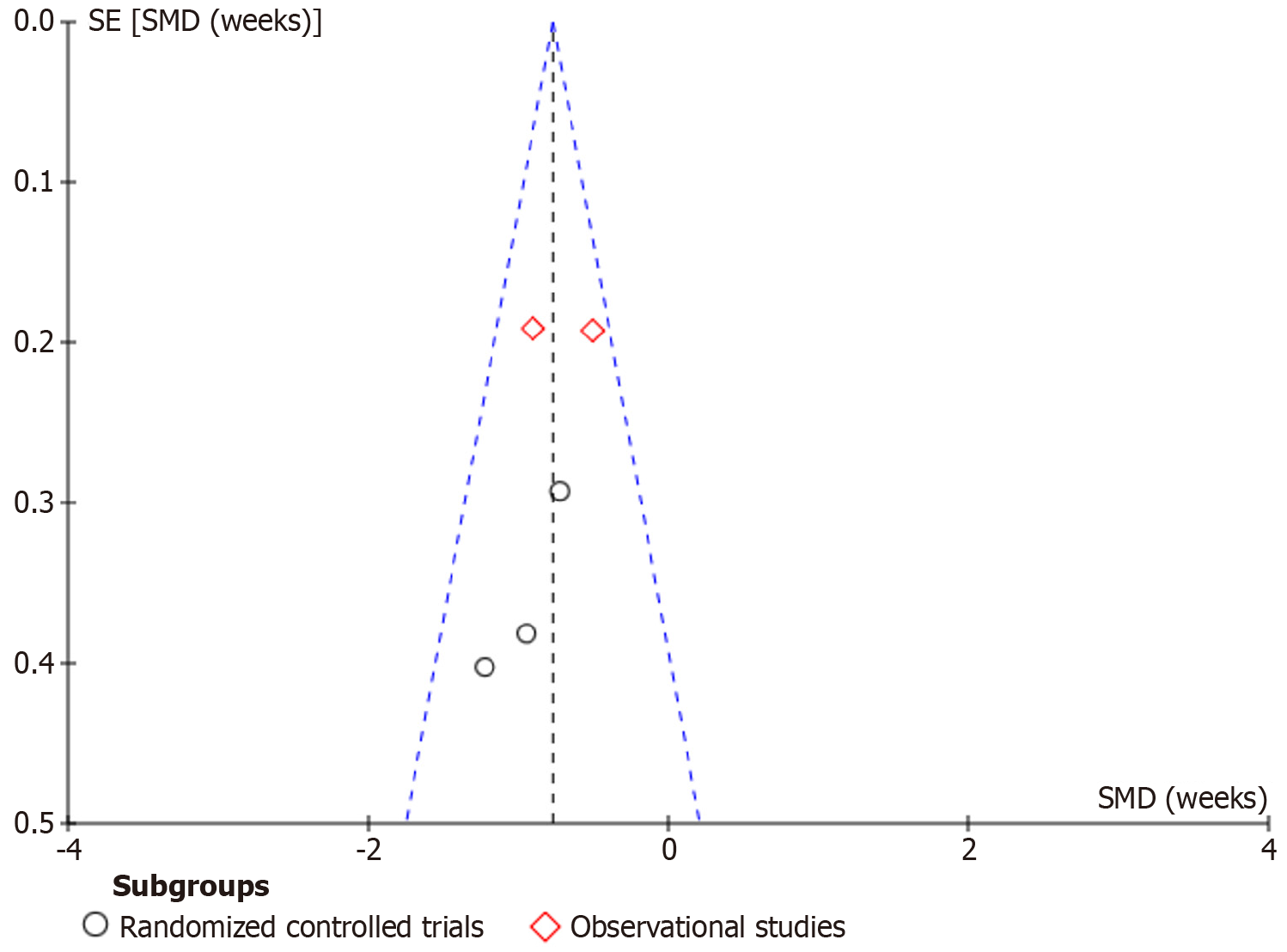

Publication bias: A funnel plot of the primary outcome variable (union time) revealed no major asymmetry (Figure 4), suggesting no strong publication bias. Both observational studies were on the positive side of the effect size, implying that observational studies are more likely to report favorable effects[21,22]. The RCTs showed more variability, including one with a large negative effect size[23-25].

This meta-analysis was the first to investigate the role of teriparatide in promoting fracture union in intertrochanteric fractures. An earlier review was conducted 4 years ago and combined femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures[12]. These fractures are different from each other with non-union more common in femoral neck fractures and malunion more common in intertrochanteric fractures[30,31]. Therefore, we conducted this study by excluding studies on femoral neck fractures[32]. We also excluded the pilot study by Chesser et al[29]. Other studies compared the use of teriparatide with bisphosphonate and were also excluded[33,34]. After applying our strict inclusion and exclusion criteria, we analyzed six studies.

Non-unions are highly uncommon in intertrochanteric fractures. However, there are concerns in elderly patients of inadequate/improper fixation, osteoporosis, and problems related to prolonged immobilization. Despite advances in the surgical fixation modalities, the 1-year mortality has not decreased, largely due to prolonged immobilization[35]. Early mobilization is a double-edged sword. While it decreases risks like deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and pneumonia, it increases the risk of fixation failure[36]. It has been observed that the more osteoporotic the bone, the less secure the fixation becomes. Surgeons typically are more reluctant to mobilize patients with severe osteoporosis. Because of this, teriparatide has been tested to determine its enhancement on the process of bony union with the hope of beginning weight bearing earlier.

Union time was our primary outcome variable, and it was accelerated in the teriparatide group. Few of the included studies measured union rates at various time points[22,24]. The percentage of fractures that achieved complete union were higher at subsequent follow-ups in the teriparatide group when compared with the control group. All fractures in the control group did eventually unite, although after a longer duration than in the teriparatide group. These data confirmed that non-unions are highly uncommon in intertrochanteric fractures. The effect of teriparatide is in the enhancement or acceleration of the process of union.

Teriparatide increases osteogenesis and enhances callus formation at the fracture site. Teriparatide has been shown to enhance union in cases of delayed union at various sites in the body[9,36]. A systematic review by Canintika and Dilogo[11] showed that daily teriparatide (20 μg subcutaneous injection) is a safe treatment for delayed union and non-union with no side effects, although the evidence was limited.

The intertrochanteric region is made up of metaphyseal cancellous bone. In elderly patients this region is often osteoporotic, leading to implant failure. Implant-related complications like hardware failure are more common in load-bearing implants like DHS compared with load-sharing intramedullary devices like PFN[21]. One of the included studies used DHS in all their patients[21], while the other studies used some form of PFN (proximal femoral nail or intramedullary nail with helical blade)[22-26]. Implant-related complications were seen more frequently in the control group compared with the teriparatide group. Since teriparatide can increase bone stock and enhance the process of union, it decreases the possibility of screw back-out/cut-out. Lag-screw cut-out, lateral screw migration, and varus collapse were observed more frequently in the control group. While the individual studies that used either DHS or PFN did show benefit of teriparatide use, the limited number of studies and the variable reporting of outcomes specific to either implant subgroups precluded any formal subgroup meta-analysis based on implant type. It appeared from the data of the individual studies that implant-related complications such as screw cut-out and varus collapse occurred more frequently in the DHS-treated control groups compared to the PFN groups[21].

The earlier, observational studies had an increased incidence of complications that contributed significantly to the overall effect[21,22]. Many of the complications comprised non-implant-related complications like pneumonia and urinary tract infections. Implant-related complications were few, especially in the more recent studies. The more recently published RCTs used PFN with helical blade made of titanium and showed a similar incidence of complications in both groups[23-25]. Early union and increased bone stock aided by teriparatide may obviate the possibility of implant-related complications.

The studies showed a trend of higher BMD values over time in the teriparatide group as compared to the controls. This observed rise in BMD supports the anabolic effect of the injectable drug, which may contribute to enhanced fracture union and reduced complication rates[21-26]. However, due to the variation in the BMD assessment methods and the time points of assessment, no meta-analysis nor direct comparison could be carried out between the different studies. Despite this heterogeneity, the similar trend towards improved BMD supports the positive clinical and radiological outcomes following teriparatide administration in this patient population.

The scoring systems used for evaluation of functional outcome data varied between studies. Therefore, no meta-analysis was performed. The functional outcome is reflective of the patient’s confidence and ability to perform a variety of tasks. Fracture union can also lead to a decrease in pain scores. Early healing may lead to better outcomes in both groups at various time points while the fracture is still uniting. Clinical outcomes in the teriparatide group may have been better at the initial follow-up due to the acceleration of healing[21,22]. However, over the long term when the fracture has completely healed, the outcomes were similar in both the teriparatide group and the control group[23,24]. The individual studies in our review did find that the gap in the functional scores of the two groups decreased with every subsequent follow-up. Thus, it is important to consider the findings of this meta-analysis within the clinical context. If we see the trend among functional scores at subsequent follow-ups, there is a convergence between both the groups across all studies, implying that teriparatide may help in better pain control, mobility, and independence during recovery in the early post-operative period. While a statistically significant reduction in the fracture union time may not necessarily translate into better long-term outcome, accelerated fracture union allows for earlier mobilization, thereby reducing secondary complications like pneumonia and deep vein thrombosis[35].

Our study had many strengths. One of the salient features of this review was the inclusion of only intertrochanteric fractures. An earlier review by Han et al[12] addressed both femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures together. Because these fractures behave differently during fracture union and the most recent systematic review was published more than 4 years ago, it was important to dedicate a recent study to intertrochanteric fractures. Additionally, the previous reviews of teriparatide in intertrochanteric fractures included a few studies[27,28] which were partially-overlapping studies of the same patient population by the same author groups, respectively[21,22]. Inclusion of fully or partially duplicated/overlapping studies would lead to an erroneous assessment of the effect of teriparatide in these fractures. We included only the studies published later to avoid duplication.

Despite the strengths in and important findings from our study, we must acknowledge some limitations. First, the quality of the individual studies varied. We could only include five comparative studies in the meta-analysis[21-25], and only two were high-quality RCTs[23,25]. The results of this review should be cautiously considered due to the lower level of evidence and few participants in the included studies. The overall sample size was relatively small, with 393 patients in the systematic review and 353 in the meta-analysis. Small sample sizes are known to limit statistical power and increase the risk of type II error. It may also reduce the generalizability of the study findings. Because of the cost of teriparatide and the requirement of self-administration over several months, these studies are challenging to conduct. Chesser et al[29] had conducted a pilot study for an RCT and found significant challenges in patient recruitment and retention. Notably, only 4% of the target population was willing to participate in the study[29]. Second, there was variation in the teriparatide regimen used in the included studies. While the daily dose was 20 μg, the duration of administration ranged from 2 months to 18 months. These variations in dosing and duration of administration are likely to influence fracture healing and complicate the pooled effect estimation. There was also variation in follow-up duration across studies, from 24 weeks to over 12 months, which introduced heterogeneity into the functional and radiological outcomes. Finally, there were other confounding factors like choice of implants, quality of reduction, age of the patients, and lack of explicit osteoporotic criteria across all studies. In the future, larger, high-quality RCTs with longer follow-ups will be required to validate the efficacy of teriparatide in enhancing fracture union and reducing complications in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures. Standardization of the injection dosing regimen, choice of implant, and follow-up protocols will help towards resolving the issues with heterogeneity and comparability.

This systematic review and meta-analysis based on six available studies demonstrated a reduction in union time for osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures, varus collapse, and incidence of complications after treatment with teriparatide. Other radiological parameters like screw back-out, screw cut-out, and femoral neck length shortening were not significant between the teriparatide and control groups. Additional RCTs with more patients are required to confirm the effect of teriparatide injection in this patient population.

| 1. | Haidukewych GJ. Intertrochanteric fractures: ten tips to improve results. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:712-719. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Shen L, Zhang Y, Shen Y, Cui Z. Antirotation proximal femoral nail versus dynamic hip screw for intertrochanteric fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2013;99:377-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Huang JW, Gao XS, Yang YF. Early prediction of implant failures in geriatric intertrochanteric fractures with single-screw cephalomedullary nailing fixation. Injury. 2022;53:576-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Templeman D, Baumgaertner MR, Leighton RK, Lindsey RW, Moed BR. Reducing complications in the surgical treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. Instr Course Lect. 2005;54:409-415. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sambandam SN, Chandrasekharan J, Mounasamy V, Mauffrey C. Intertrochanteric fractures: a review of fixation methods. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2016;26:339-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Blick SK, Dhillon S, Keam SJ. Teriparatide: a review of its use in osteoporosis. Drugs. 2008;68:2709-2737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hodsman AB, Bauer DC, Dempster DW, Dian L, Hanley DA, Harris ST, Kendler DL, McClung MR, Miller PD, Olszynski WP, Orwoll E, Yuen CK. Parathyroid hormone and teriparatide for the treatment of osteoporosis: a review of the evidence and suggested guidelines for its use. Endocr Rev. 2005;26:688-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Collinge C, Favela J. Use of teriparatide in osteoporotic fracture patients. Injury. 2016;47 Suppl 1:S36-S38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Babu S, Sandiford NA, Vrahas M. Use of Teriparatide to improve fracture healing: What is the evidence? World J Orthop. 2015;6:457-461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sain A, Bansal H, Pattabiraman K, Sharma V. Present and future scope of recombinant parathyroid hormone therapy in orthopaedics. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2021;17:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Canintika AF, Dilogo IH. Teriparatide for treating delayed union and nonunion: A systematic review. J Clin Orthop Trauma. 2020;11:S107-S112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han S, Wen SM, Zhao QP, Huang H, Wang H, Cong YX, Shang K, Ke C, Zhuang Y, Zhang BF. The Efficacy of Teriparatide in Improving Fracture Healing in Hip Fractures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:5914502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Keshav K, Kaustubh K, Mishra P. Effect of Teriparatide in osteoporotic intertrochanteric fractures for improving fracture union: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Available from https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42024502631. |

| 14. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 48670] [Article Influence: 2862.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Binkley JM, Stratford PW, Lott SA, Riddle DL. The Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS): scale development, measurement properties, and clinical application. North American Orthopaedic Rehabilitation Research Network. Phys Ther. 1999;79:371-383. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Bhandari M, Chiavaras M, Ayeni O, Chakraverrty R, Parasu N, Choudur H, Bains S, Sprague S, Petrisor B; Assessment Group for Radiographic Evaluation and Evidence (AGREE) Study Group (AGREE Investigators Writing Committee). Assessment of radiographic fracture healing in patients with operatively treated femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2013;27:e213-e219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Higgins JPT, Savovic J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized trial. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019: 205-228. |

| 18. | Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:712-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3743] [Cited by in RCA: 6159] [Article Influence: 267.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 3310] [Article Influence: 551.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Higgins JPT, Li T, Deeks JJ. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2nd ed. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons, 2019: 143–176. |

| 21. | Huang TW, Chuang PY, Lin SJ, Lee CY, Huang KC, Shih HN, Lee MS, Hsu RW, Shen WJ. Teriparatide Improves Fracture Healing and Early Functional Recovery in Treatment of Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Fractures. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim SJ, Park HS, Lee DW, Lee JW. Short-term daily teriparatide improve postoperative functional outcome and fracture healing in unstable intertrochanteric fractures. Injury. 2019;50:1364-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rana A, Aggarwal S, Bachhal V, Hooda A, Jindal K, Dhillon MS. Role of supplemental teriparatide therapy in management of osteoporotic intertrochanteric femur fractures. Int J Burns Trauma. 2021;11:234-244. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Mishra S, Satapathy D, Samal S, Zion N, Lodh U. Role of Supplemental Teriparatide Therapy to Augment Functional and Radiological Outcomes in Osteoporotic Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures in the Elderly Population. Cureus. 2022;14:e26190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tanavalee C, Ngarmukos S, Amarase C, Tantavisut S, Jaruthien N, Tanavalee A. A randomized controlled trial of teriparatide for accelerating bone union and improving clinical outcomes in patients with pertrochanteric fracture fixation. Sci Rep. 2025;15:19465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Aggarwal HO, Singh M, Garg A, Basoa S, Chalana A. Effect of teriperatide in healing of intertrochanteric fractures in elderly persons. Int J Life Sci Biotechnol Pharma Res. 2025;14:57-65. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Huang TW, Yang TY, Huang KC, Peng KT, Lee MS, Hsu RW. Effect of teriparatide on unstable pertrochanteric fractures. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:568390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kim SJ, Park HS, Lee DW, Lee JW. Does short-term weekly teriparatide improve healing in unstable intertrochanteric fractures? J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2018;26:2309499018802485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chesser TJ, Fox R, Harding K, Halliday R, Barnfield S, Willett K, Lamb S, Yau C, Javaid MK, Gray AC, Young J, Taylor H, Shah K, Greenwood R. The administration of intermittent parathyroid hormone affects functional recovery from trochanteric fractured neck of femur: a randomised prospective mixed method pilot study. Bone Joint J. 2016;98-B:840-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Arshi A, Su L, Lee C, Sassoon AA, Zeegen EN, Stavrakis AI. Comparison of complication profiles for femoral neck, intertrochanteric, and subtrochanteric geriatric hip fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2023;143:49-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bhandari M, Jin L, See K, Burge R, Gilchrist N, Witvrouw R, Krohn KD, Warner MR, Ahmad QI, Mitlak B. Does Teriparatide Improve Femoral Neck Fracture Healing: Results From A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1234-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Aspenberg P, Malouf J, Tarantino U, García-Hernández PA, Corradini C, Overgaard S, Stepan JJ, Borris L, Lespessailles E, Frihagen F, Papavasiliou K, Petto H, Caeiro JR, Marin F. Effects of Teriparatide Compared with Risedronate on Recovery After Pertrochanteric Hip Fracture: Results of a Randomized, Active-Controlled, Double-Blind Clinical Trial at 26 Weeks. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1868-1878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Malouf-Sierra J, Tarantino U, García-Hernández PA, Corradini C, Overgaard S, Stepan JJ, Borris L, Lespessailles E, Frihagen F, Papavasiliou K, Petto H, Aspenberg P, Caeiro JR, Marin F. Effect of Teriparatide or Risedronate in Elderly Patients With a Recent Pertrochanteric Hip Fracture: Final Results of a 78-Week Randomized Clinical Trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2017;32:1040-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint PK. Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43:464-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Agarwal N, Feng T, Maclullich A, Duckworth A, Clement N. Early mobilisation after hip fracture surgery is associated with improved patient outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22:e1863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gariffo G, Bottai V, Falcinelli F, Di Sacco F, Cifali R, Troiano E, Capanna R, Mondanelli N, Giannotti S. Use of Teriparatide in preventing delayed bone healing and nonunion: a multicentric study on a series of 20 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/