Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113526

Revised: September 23, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 160 Days and 21.6 Hours

Anxiety is a common issue among non-acute surgical fracture patients. Non-pharmacological interventions are needed. This meta-analysis aims to synthesize evidence on the efficacy of music therapy for anxiety reduction in this population.

To evaluate the effect of music therapy on anxiety in non-acute surgical fracture patients.

We systematically searched CNKI, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, VIP, and MEDLINE databases for randomized controlled trials. Data were pooled using a random-effects model. The primary outcome was anxiety scores measured by standardized scales.

Twelve randomized-controlled trials comprising 1257 patients (628 receiving music therapy, 629 in control groups) are included. Music therapy markedly re

Music therapy significantly reduces anxiety in non-acute surgical fracture patients and should be considered as a complementary therapy.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis offers robust evidence that music therapy - an affordable, non-invasive intervention - effectively eases anxiety in patients recovering from non-acute surgical fractures. Its findings back the inclusion of music therapy in standard clinical rehabilitation protocols. This integration can enhance patients’ psychological outcomes and may reduce the need for pharmacological treatments, highlighting a practical, low-cost way to improve post-surgery care.

- Citation: Tang YL, Zhao YX, Wang X. Music therapy for anxiety reduction in non-acute surgical fracture patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 113526

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/113526.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113526

Recent surveys indicate that the number of individuals suffering from traumatic fractures in China has been increasing annually[1]. Approximately 26.6% of fracture patients are reported to experience anxiety symptoms[2]. Anxiety is therefore relatively common in this population, often manifesting as restlessness, fear, and insomnia, all of which can significantly impede postoperative recovery[1]. Pain associated with fractures is typically attributed to congestion and swelling of the surrounding soft tissues, which may irritate local nerves and exacerbate discomfort. In addition, the prolonged immobilization required during the recovery process can contribute to psychological distress, warranting close clinical attention[3]. Furthermore, anxiety and depression frequently co-occur. Consequently, patients exhibiting anxiety symptoms after a fracture may also experience varying degrees of depressive symptoms, further complicating both emotional and physical rehabilitation.

In clinical practice, pharmacological interventions have traditionally been the primary approach for alleviating anxiety symptoms, supplemented by various non-pharmacological treatments. Evidence indicates that serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) plays a crucial role in both sleep regulation and the pathophysiology of anxiety disorders. Most anxiolytic medications exert their therapeutic effects by modulating 5-hydroxytryptamine transmission[4]. Consequently, pharmacological treatments are characterized by high specificity and a rapid onset of action, offering significant short-term benefits for patients with anxiety[5]. However, pharmacological treatment also has notable limitations. In clinical settings, therapeutic outcomes are often suboptimal. This is partly due to the side effects associated with anxiolytic medications, which may include emotional blunting and neurological impairment[6]. Moreover, discontinuation of medication frequently leads to symptom relapse, contributing to drug dependence and, in some cases, misuse[7]. In addition, poor treatment adherence among patients with anxiety disorders can further compromise therapeutic efficacy[8]. Given these challenges, the advantages of non-pharmacological interventions have gained increasing recognition. Such approaches are characterized by better patient compliance, fewer adverse effects, and greater long-term sustainability, leading to growing interest and application in both clinical practice and research[9]. In recent years, non-drug treatment methods represented by music therapy for treating psychological problems in patients with mild to moderate diseases have been paid more and more attention by scholars at home and abroad as well as patient families, due to their advantages such as safety, simplicity, low cost, and no limitation by the venue[10]. Therefore, music therapy stands out in the treatment of mild to moderate psychological problems. Regarding its definition, the definition given by Bruscia[11] is that “Music therapy is a systematic intervention process. In this process, the therapist uses music to create different situations to help patients experience healing. And the therapeutic relationship, which is gradually established during the treatment process and serves as an excellent bridge for communication, enables patients to achieve the goal of good health”. The cognitive-neurological hypothesis posits that music modulates activity in limbic structures, which are critically involved in the generation, maintenance, and regulation of emotion[12]. Music-induced pleasurable experience is closely linked to the brain’s reward circuitry, including the striatum, ventral tegmental area, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex[13]. Accordingly, once the limbic system is activated, endogenous opioids-especially β-endorphin are released. This en

A recent meta-analysis examining the effects of music therapy on anxiety in orthopedic surgery patients reported significant reductions in both postoperative anxiety and pain scores[16]. However, the therapeutic benefits of music are not limited to intraoperative or immediate postoperative contexts. Patients with non-acute surgical fractures - those undergoing conservative treatment or elective surgery - although not in life-threatening conditions, typically experience prolonged recovery periods during which anxiety remains prevalent. Implementing music therapy as part of general clinical care for these patients may therefore have meaningful psychological benefits. Accordingly, the present study aims to systematically review and quantitatively synthesize evidence from randomized controlled trials to evaluate the effects of music interventions on anxiety among patients with clinically non-acute surgical fractures.

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA statement[17].

Search strategy: We created a search strategy to identify eligible articles from MEDLINE (Ovid Technologies), EMBASE (Ovid Technologies), PubMed, Cochrane, CNKI, and VIP Database. The retrieval time is from the establishment to February 2024. The search strategies were slightly customized for different databases. The search terms were: “music therapy/music/songs”; “fracture/bone fracture/elbow fracture/skull”; “anxiety/nervousness/anxiousness/negative emotion”; “randomized controlled trial/random/RCT”. In addition, the reference lists of the retrieved studies are cross - checked and without language restrictions. However, the search was limited to Chinese and English databases, potentially omitting relevant studies published in other languages.

Selection process: Two researchers independently conducted a dual screening for relevance on the titles and abstracts of the articles identified in the search, as well as on the full texts of the articles that were deemed potentially eligible. The inclusion criteria for the systematic review are as follows: (1) Studies that are randomized controlled trials; (2) The target population is patients with clinically non-acute surgical fractures; (3) To investigate the impact of music intervention on anxiety; (4) Use any recorded or live music intervention that has melody, harmony and rhythm; (5) Interventions provided by researchers or music therapists; and (6) Patient reported outcomes: The primary indicator is the anxiety score, including the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, and Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders. The secondary indicators are pain and depression. The exclusion criteria are as follows: (1) The target population is patients with congenital fractures; (2) Studies for which the full text cannot be obtained; and (3) Studies in which data cannot be extracted or the data is incomplete; If there is an overlap of the population among the studies, only the most recent or comprehensive study will be included. These studies will only be included in the meta-analysis when they include the measurement of the dispersion of specific outcomes. If there is a disagreement regarding the inclusion of an article, a third researcher will be consulted.

Data collection: The data were independently extracted and checked by three authors. The EndNote X20 software is used to eliminate duplicates and screen the titles and abstracts. The following research characteristics were recorded: The authors, publication year, journal, number of patients, gender ratio, average age, inclusion period, average follow-up, ethical approval, outcome scale used, fracture type, timing of the music intervention (during or after fracture treatment), different types of recorded live music interventions and relevant descriptions of the interventions, as well as the type of the control group were recorded. The primary outcomes were the mean pain scores (including the measurement of dispersion) of the intervention group and the control group measured at baseline and at the end of the study or during the last follow-up. When available, relevant outcome data on the changes compared to the baseline were also extracted, including the measurement of dispersion for both the intervention group and the control group. If a study used multiple time points, only the first and the last time points were considered.

The quality of the included papers was evaluated using two methods. The first method is to use the method for evaluating the quality of randomized controlled trials in the Cochrane Systematic Review Manual 5.1.0 to conduct a methodological quality assessment of the included papers. It includes the randomization method, the situation of allocation concealment, the implementation of blinding for patients and physicians, the situation of outcome evaluation, the completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other situations of bias, etc. The second method is to conduct the evaluation by using the modified Jadad scale. The modified Jadad scoring method scores according to aspects such as the generation of the random sequence in the study, the method of allocation concealment, and whether the details of participants’ withdrawal or dropout are described. Studies with a total score of 4 to 7 points are regarded as high-quality studies, while those with a score of 1 to 3 points are low-quality studies. To ensure the reliability of the screening process and avoid subjective biases, the screening of literatures and the methodological quality assessment were independently completed and checked by two researchers. In case of any disagreement during the screening process, it would be resolved through negotiation. When differences exist, the thesis supervisor (a third party) will make the decision.

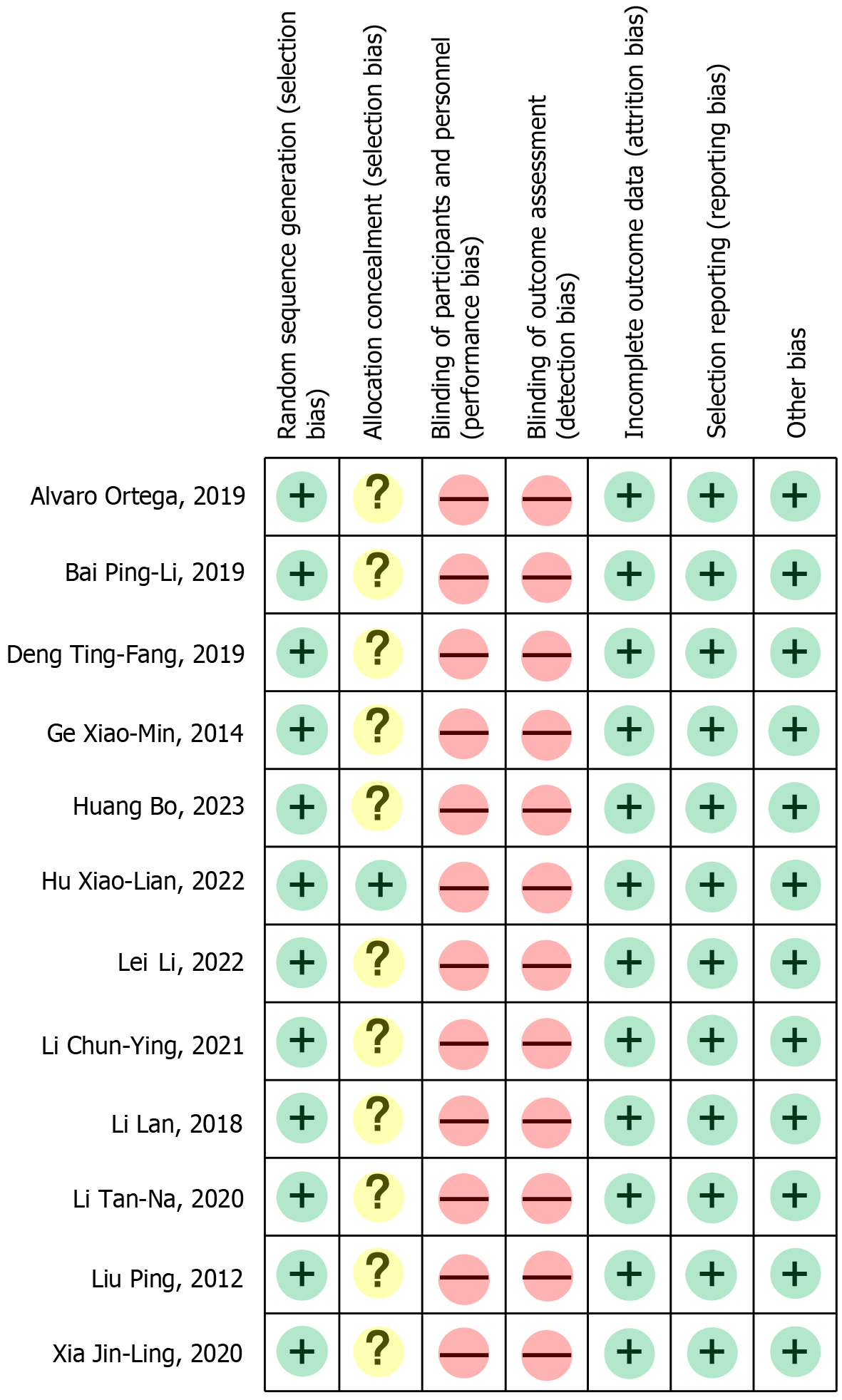

In Figure 1, all the literatures present a low risk of bias and are of relatively high quality. In Figure 1, “+” indicates meeting the standard, and “-” indicates not meeting the standard. Figure 2 is a statistical chart showing the proportion of each item in the methodological evaluation. Table 1 is the Jadad evaluation. Since all the studies in the papers required the research subjects or their family members to sign the informed consent forms, it was impossible to ensure the blinding of the experiments. Therefore, for all the papers, the item of “blinding” is marked as “-”.

| Ref. | Method | Objects (mean ± SD) | Gender-specific counts by group (male/female) | Fracture mechanism | Intervention measures | Patient reported outcomes |

| Ortega et al[18], 2019 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 17 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 30.5 years old and an average disease course of 10.7 days; there were 19 cases in the control group, with an average age of 30.5 years old and an average disease course of 10.7 days | Experimental group (10/7); control group (12/7) | Displaced nasal bone fracture | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Exposure time was 10 minutes before the intervention, during the intervention, and 10 minutes after the intervention.by the same over-the-ear Bluetooth headphones and set the music intensity themselves; the control group: Routine clinical treatment | 1,2 |

| Hu[19], 2022 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 52 cases in the experimental group, with an age of 71.96 ± 8.62 years old; there were 53 cases in the control group, with an age of 71.92 ± 9.12 years old | Experimental group (18/34); control group (21/32) | Elderly patients with hip fractures | Traditional five - tones therapy; the experimental group: On the basis of the control group, when the Yu-mode music corresponding to the kidney was played, the ambient light was adjusted to green light (illuminance 15 lux); the control group: Select yang-mode pieces in the Yu mode, which corresponds to the kidney, and in the Jue mode, which corresponds to the liver. Edit them into a single 30-minute track, beginning with 15 minutes of Yu-mode music followed by 15 minutes of Jue-mode music, and save the file in lossless APE format on the playback device. Patients receive one session every day between 18:00 and 20:00, each lasting 30 minutes, 5 consecutive days per week. One treatment cycle is 2 weeks, and the study comprises two cycles | 1,3,4 |

| Bai et al[20], 2019 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 50 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 76.5 ± 5.14 years old; there were 50 cases in the control group, with an average age of 76.5 ± 6.90 years old | Experimental group (28/22); control group (26/24) | Elderly patients with hip fractures | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Based on routine nursing care, implement music therapy as psychological nursing, using soothing melodies and adjusting the volume to 15-35 dB; the control group: Routine nursing intervention | 1,3 |

| Xia and Wang[23], 2020 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 100 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 7.12 ± 2.13 years old; there were 100 cases in the control group, with an average age of 6.65 ± 1.13 years old | Experimental group (57/43); control group (56/44) | Children with fractures | Visual music therapy; the experimental group: Awakening phase: Using a visual music-intervention device, select music and rhythms that match the child’s preferences and let the child listen quietly. Following phase: Shift to active music-therapy interventions. Leading phase: Place the child at the center; nurses increase interactive situational play with the child; the control group: Routine nursing intervention | 1 |

| Deng et al[25], 2019 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 50 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 6.32 ± 1.05 years old; there were 50 cases in the control group, with an average age of 6.12 ± 1.34 years old | Experimental group (25/25); control group (26/24) | Children with elbow fractures | Visual music therapy; the experimental group: Awakening phase: Using a visual music-intervention device, select music and rhythms that match the child’s preferences and let the child listen quietly. Following phase: Shift to active music-therapy interventions. Leading phase: Place the child at the center; nurses increase interactive situational play with the child; the control group: Routine nursing intervention | 1 |

| Li et al[21], 2020 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 47 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 8.40 ± 0.68 years old and an average course of disease of 6.99 ± 0.49 hours; there were 46 cases in the control group, with an average age of 8.43 ± 0.71 years old and an average disease course of 7.02 ± 0.51 hours | Experimental group (29/18); control group (27/19) | Children with elbow fractures | Visual music therapy; the experimental group: Awakening phase: A visual music-intervention device is used to select music and rhythms preferred by the child, who listens quietly; 15-30 minutes per session, 2 sessions daily. Following phase: Active music-therapy interventions dominate; 30 minutes per session, 1 session daily. Leading phase: The child is the focus; nurses engage in situational role-play with the child; 15-20 minutes per session, 1 session daily. Continuous intervention for 30 days; the control group: Routine nursing intervention. Continuous intervention for 30 days | 1,2 |

| Li and Xiao[24], 2021 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 60 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 35.63 ± 3.48 years old; there were 60 cases in the control group, with an average age of 35.14 ± 3.41 years old | Experimental group (37/23); control group (36/24) | Bone trauma and fracture | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Psychological nursing combined with music therapy. Fifteen gentle, relaxing pieces were selected from each patient’s preferred background music to guide the therapy; the control group: Routine psychological nursing intervention | 1,2,3,4 |

| Huang and Fang[22], 2023 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 100 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 62.32 ± 9.45 years old; there were 100 cases in the control group, with an average age of 63.75 ± 9.72 years old | Experimental group (54/46); control group (53/47) | Patients with hypertension and limb fractures | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Start listening relaxing music 20 minutes before surgery; the patient listens through headphones at 40-60 dB with the tracks on loop; the control group: Routine psychological nursing intervention | 1,2 |

| Ge et al[26], 2014 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 45 cases in the experimental group, there were 45 cases in the control group. Ages ranged from 18 to 65 years old, with no statistically significant difference between groups | Not reported | Patients with lower limb fractures | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Music intervention was administered separately after the morning meal, after the noon nap, and before bedtime at night; each session lasted 20-30 minutes and was delivered via headphones; the control group: Routine clinical treatment | 1,3 |

| Liu et al[27], 2012 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 20 cases in the experimental group, there were 20 cases in the control group. The average age is 33 years old, with no statistically significant difference between groups | All participants (24/16) | Patients with orbital wall fractures | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Each music-therapy session lasted approximately 40 minutes and was conducted on the day of admission, one day before the intervention, and one day after the intervention. Participants wore headphones, and the volume was kept below 70 dB; the control group: Routine clinical treatment | 1,2 |

| Li and Yang[28], 2018 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 57 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 62.9 ± 4.5 years old and an average course of disease of 4.7 ± 2.3 hours; there were 56 cases in the control group, with an average age of 62.4 ± 4.1 years old and an average course of disease of 4.3 ± 2.5 hours | Experimental group (28/29); control group (28/28) | Traumatic pelvic fracture | Listening - based music therapy; the experimental group: Post-breakfast each morning, patients were escorted by clinical staff to the music-oxygen lounge for a single 30-minute session; the control group: Conventional rehabilitation therapy | 1,2,3 |

| Lei et al[29], 2022 | Randomized controlled, non-blinded | There were 30 cases in the experimental group, with an average age of 69.26 ± 5.35 years old; there were 30 cases in the control group, with an average age of 70.22 ± 5.68 years old | Experimental group (16/14); control group (15/15) | Patients with hip fractures | Traditional five - tones therapy; the experimental group: The mean nursing duration was 17.13 ± 0.57 days. On the basis of standard admission care, patients received syndrome-based traditional Chinese medicine treatment with five-element music therapy delivered via headphones at 40-50 dB; each session lasted 20-30 minutes and was administered once in the morning and once at noon; the control group: The mean nursing duration was 16.97 ± 0.62 days, during which routine nursing care was provided | 1,2 |

The STATA 17 software was applied to conduct the meta-analysis. This study mainly conducts a meta-analysis on the selected 12 pieces of continuous data, calculates the standardized mean difference (SMD), and computes the 95% confidence interval (CI). The heterogeneity of the studies was analyzed using the χ2 test. If I2 < 50% and P > 0.10, it indicates that the studies are homogeneous, and the fixed-effect model is selected. If I2 ≥ 50% and P < 0.10, it indicates that there is heterogeneity among the studies, and the random-effects model is selected. Publication bias was analyzed using the “Egger’s plot” and the “funnel plot”. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

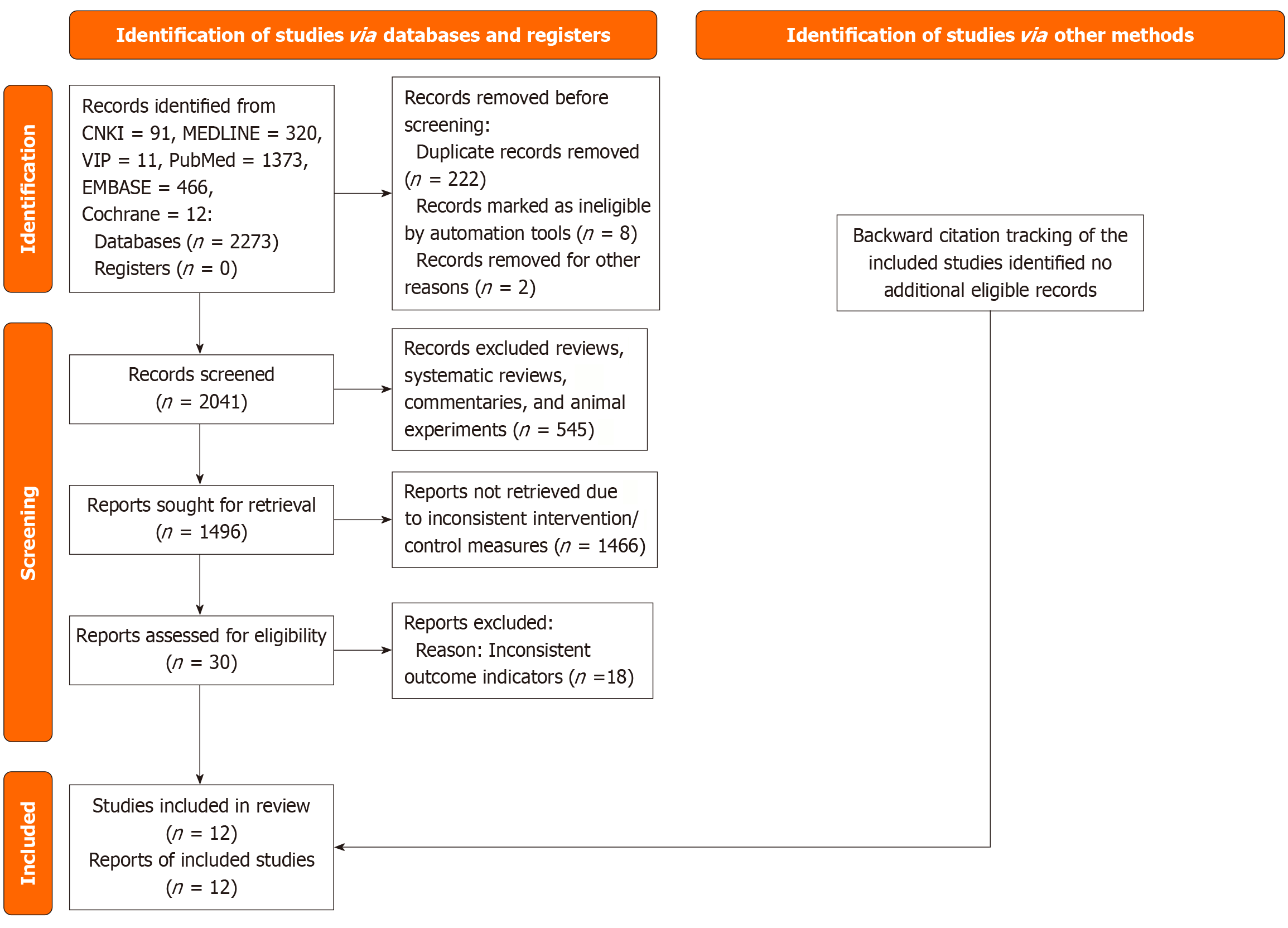

A total of 2273 studies were initially retrieved. After the preliminary screening and re-screening, 12 studies were finally included, among which one is an English study and 11 are Chinese studies (Figure 3).

The 12 included studies involved 1257 fracture patients. The basic characteristics of the studies are shown in Table 1.

A total of 12 randomized controlled trials were included in this study. Among them, 5 studies[18-22] described the specific methods of randomization. Although the remaining 7 studies[23-29] did not specifically describe the methods of random allocation, they all adopted random grouping methods. Considering the openness of music therapy and the fact that all the studies in the articles required the research subjects or their family members to sign informed consent forms, it was impossible to ensure the blinding of the experiments. Therefore, the item of blinding in all the studies was marked as “-”. The 12 studies all ensured the rigor of the experiments and the stability of the results.

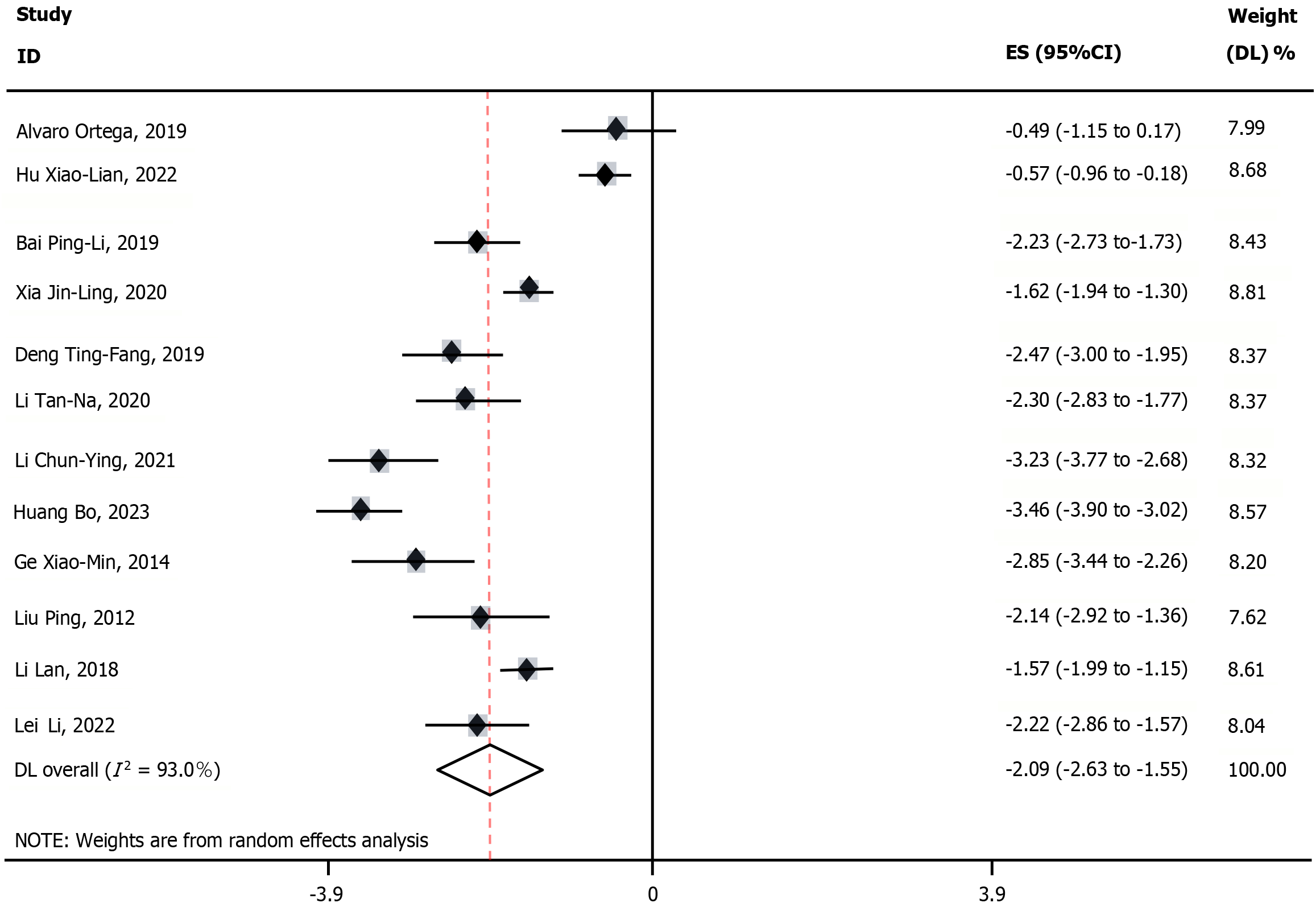

The total effect of music therapy intervention on the anxiety of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings: The intervention effects on anxiety were reported in all 12 pieces of studies. Scales such as the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, or Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders were used. In all these scales, the higher the score, the more severe the degree of anxiety. Meta-analysis display: Music therapy has a better effect on the anxiety of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings than the control group (SMD = -2.09, 95%CI: -2.63 to -1.55, P < 0.001). Among the intervention measures, 3 studies[21,23,25] used visual music therapy, 7 studies[18,20,22,24,26-28] adopted music therapy mainly focusing on listening, and 2 studies[18,29] applied traditional five-tone music therapy. Subgroup analyses were then conducted respectively. The differences were all statistically significant (P < 0.05). The pooled SMD was -2.09 (95%CI: -2.63 to -1.55), indicating a moderate to large reduction in anxiety scores, which can be considered clinically meaningful for patients undergoing recovery from fracture (Table 2).

| Intervention measures | The number of included studies | Sample size | Heterogeneity test | Meta-analysis results | ||||

| Intervention group | Control group | I2 (%) | P value | Effect model | SMD (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Musical therapy | 12 | 628 | 629 | 93.00 | < 0.001 | Random | -2.09 (-2.63 to -1.55) | < 0.001 |

| Listening - based music therapy | 7 | 349 | 350 | 92.60 | < 0.001 | Random | -2.38 (-2.58 to -2.18) | < 0.001 |

| Visual music therapy | 3 | 197 | 196 | 79.30 | 0.008 | Random | -1.95 (-2.19 to -1.71) | < 0.001 |

| Traditional five - tones therapy | 2 | 82 | 83 | 94.50 | < 0.001 | Random | -1.01 (-1.34 to -0.67) | < 0.001 |

The total effect of music therapy intervention on the pain of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings: Seven pieces of study[18,21,22,24,27-29] reported the intervention effects on pain. The Visual Analogue Scale was used, and the higher the score, the greater the degree of pain. Meta-analysis display: Music therapy has a better effect on the pain of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings than the control group (SMD = -2.22, 95%CI: -3.39 to -1.05, P < 0.001; Table 3).

| Intervention Measures | The number of included studies | Sample size | Heterogeneity test | Meta-analysis results | ||||

| Intervention group | Control group | I2 (%) | P value | Effect model | SMD (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Pain | 7 | 331 | 331 | 97.10 | < 0.001 | Random | -2.22 (-3.39 to -1.05) | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 5 | 264 | 264 | 96.60 | < 0.001 | Random | -2.05 (-3.75 to -1.25) | < 0.001 |

The total effect of music therapy intervention on the depression of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings: Five pieces of study[19,20,24,26,28] reported the intervention effects on depression. The Self-Rating Depression Scale was used, and the higher the score, the more severe the degree of depression. Meta-analysis display: Music therapy has a better effect on the depression of patients with non-acute surgical fractures in clinical settings than the control group (SMD = -2.05, 95%CI: -3.75 to -1.25, P < 0.001; Table 3).

Heterogeneity test for the 12 pieces of study included in this study, after the heterogeneity test, I2 = 93.0% > 50%, and the P value of the Q test is less than 0.1, which indicates that there is a strong heterogeneity among the selected studies in this study. A random effects model can be chosen for the meta-analysis, or the causes of the heterogeneity can be further investigated. Based on the continuous data of this study, it is highly suspected that the source of heterogeneity is the inconsistency of the anxiety assessment scales. Subsequent subgroup analyses will be conducted according to the classification of the scales.

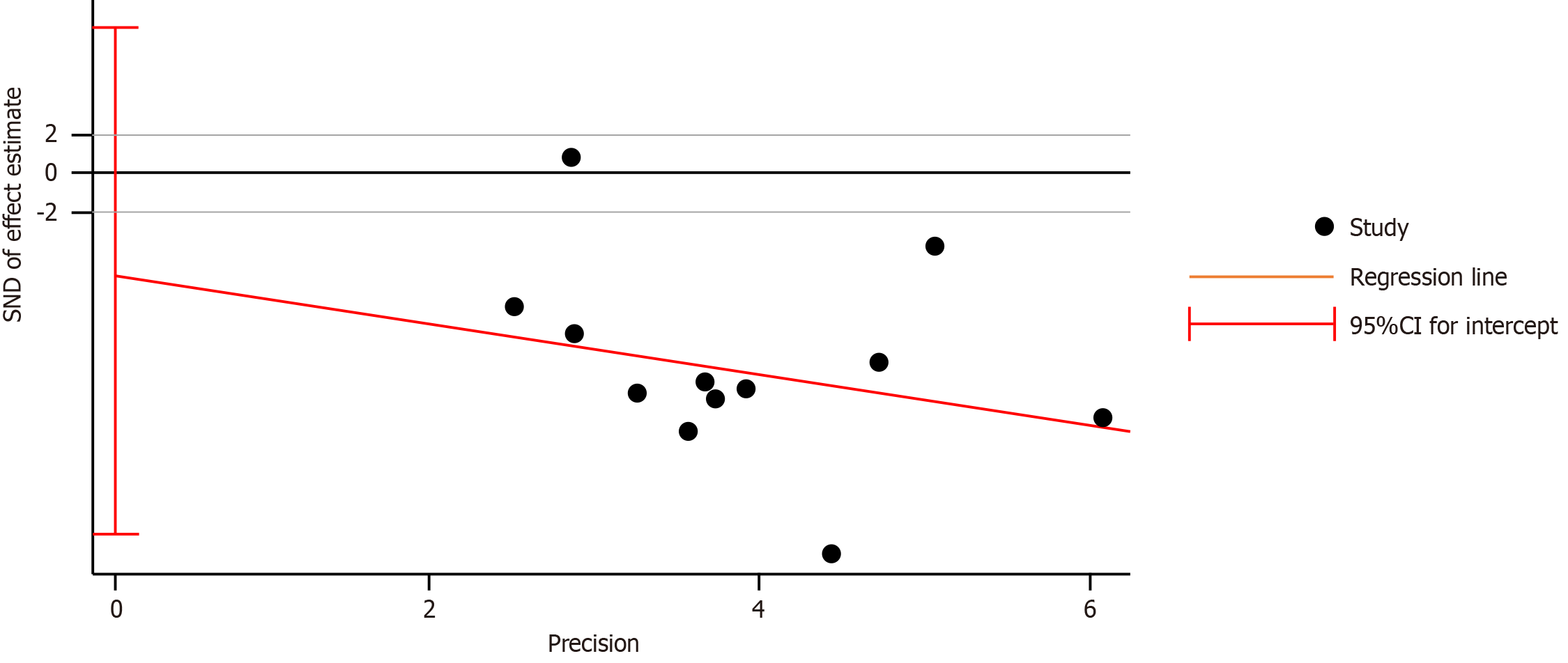

For the 12 pieces of study as a whole, a random effects model was selected for the meta-analysis, and the results are as follows: (1) The results of the meta-analysis using the random effects model show that the average anxiety score of the experimental group is 2.09 points lower than that of the control group, and this degree of difference is statistically significant, with P < 0.05; (2) Sensitivity analysis of the 12 studies shows that none significantly interferes with the meta-analysis results, indicating good stability of this study; and (3) Meta-regression to investigate the sources of heterogeneity based on the suspicion that the heterogeneity is caused by the differences in scales, a meta-regression was conducted with the effect size as the dependent variable and the scale type as the independent variable. The result is that the P value of the independent variable “scale type” is 0.459 > 0.05. Therefore, it does not have a significant impact on the effect size, so the cause of the heterogeneity is not due to the differences in measurement scales. It is suspected that the clinical heterogeneity may be the cause. For example, it may be caused by differences in the subjects of clinical trials or the treatment environments. Bias test by plotting the Egger’s plot for the 12 continuous - data papers in this study, the results are as Figure 4. The results of the meta-analysis are as Table 4. As can be seen from the table, the P value is 0.381 > 0.05, indicating that there is no obvious publication bias.

| Std_Eff | Coefficient | SE | t | P value > |t| | 95%CI |

| Slope | -0.9803055 | 1.137004 | -0.86 | 0.409 | -3.51370 to 1.553098 |

| Bias | -4.20985 | 4.588638 | -0.92 | 0.381 | -14.43397 to 6.014273 |

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrates that music therapy is an effective non-pharmacological intervention for reducing anxiety in non-acute surgical fracture patients. Our findings, synthesizing data from 12 studies, primarily indicate that music therapy can reduce anxiety and depression in non-acute surgical fracture patients. This section will discuss these findings in the context of existing study, explore potential mechanisms, and consider the clinical implications and limitations.

Anxiety and depression are common psychological concerns among patients with fractures. These conditions not only diminish patients’ quality of life but also adversely affect rehabilitation outcomes. Without timely recognition and intervention, they can lead to reduced treatment adherence and poorer prognoses. This systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effects of music therapy on anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with non-acute surgical fractures. The findings indicate that music therapy significantly alleviates both anxiety and depression, consistent with results from previous studies. During the recovery period, fracture patients often experience worries about injury severity, delayed healing, or potential disability, which may interfere with their daily functioning and heighten their fear of pain. Consequently, excessive preoccupation with their condition can lead to persistent anxiety[30].

Exploration of the mechanism of music therapy: The findings of this study indicate that music therapy can effectively reduce anxiety and depression in patients. This effect is mediated through multiple physiological and neuropsychological pathways. Music influences muscles, blood vessels, and organs via the auditory system and auditory nerves, while also modulating central nervous system activity through the reticular formation. This coordination across the cerebral cortex helps regulate the secretion of neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine and dopamine. When the rhythm, frequency, and intensity of music align with the body’s internal rhythms, it can produce calming, analgesic, and relaxing effects[31], thereby alleviating tension and anxiety and improving patients’ psychological state. In addition, music stimulates the limbic system, which is closely linked to emotional processing, and promotes endorphin release. This regulation of the endocrine system, together with positive effects on circulation and respiration, contributes to pain reduction[32]. The release of endorphins not only mitigates pain but also induces pleasure, further alleviating anxiety and depressive symptoms. Moreover, music therapy has been shown to lower plasma cortisol levels, which also contributes to reductions in anxiety and depression[33]. Collectively, these mechanisms highlight the multifaceted ways in which music therapy can enhance psychological well-being in patients.

Comparison of music therapy and pharmacotherapy: Compared with pharmacotherapy, music therapy offers several notable advantages. Although medications can act quickly, they are often accompanied by side effects, including emotional blunting and neurological impairment[6]. Additionally, pharmacological treatments carry the risk of dependence, and symptoms frequently recur after discontinuation[7]. Clinical evidence indicates that combining music therapy with pharmacotherapy can more effectively reduce anxiety and alleviate depressive symptoms than pharmacotherapy alone[34]. Beyond improving mood, music therapy can enhance patients’ quality of life and support rehabilitation outcomes. Consistent with these findings, the results of this meta-analysis demonstrate that music therapy produces significantly greater reductions in anxiety and depression among patients with non-acute surgical fractures compared with control interventions. These results underscore the importance of addressing psychological well-being alongside physical recovery in clinical practice, highlighting music therapy as a valuable adjunct to conventional care.

Application of traditional five-element music therapy: Traditional five-element music therapy is a form of music therapy rooted in Chinese holistic philosophy. It integrates the five elements theory (wood, fire, earth, metal, water) with the five tones (Jue, Zhi, Gong, Shang, Yu), the five viscera (liver, heart, spleen, lung, kidney), and the five emotions (anger, joy, pensiveness, sorrow, fear). By applying music dialectically according to individual needs, timing, and context, this therapy aims to promote health, prevent disease, and support treatment through the psychological and physiological experiences elicited by the interaction between music and the body[35]. Research indicates that receptive five-element music can effectively regulate anxiety and pain levels[36]. In a study by Chen[37], the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression scale demonstrated that five-element music improved depressive symptoms in patients, accompanied by reductions in serum levels of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, and IL-6, which are typically elevated in depression. Consistently, Hu[19] reported that traditional five-element music therapy significantly alleviated anxiety in patients. These findings suggest that incorporating elements of traditional Chinese music, such as the five elements, can serve as a culturally sensitive and effective adjunct in psychological interventions for fracture patients, enhancing the overall impact of music therapy on mental health.

Comparison with other related studies: The findings of this study are consistent with those of numerous previous investigations. For example, McKinney and Honig[33] reported that music therapy can reduce plasma cortisol levels, thereby alleviating anxiety and depressive symptoms. Similarly, Li et al[38] found that soothing music promotes muscle relaxation, enhances feelings of comfort and well-being, and that music with a lively rhythm can energize patients and reduce fatigue. Music therapy has also been shown to dilate blood vessels, lower heart rate and myocardial oxygen consumption, and mitigate anxiety and fear. Furthermore, Zhou and Wu[39] demonstrated through modern imaging techniques that listening to music activates bilateral brain regions and paralimbic structures, contributing to reductions in depressive symptoms. Collectively, these findings reinforce the conclusion of the present study: Music therapy serves as an effective non-pharmacological intervention for alleviating anxiety and depression in patients with non-acute surgical fractures.

Pain is a prominent clinical symptom in patients with fractures and can have a substantial negative impact, reducing quality of life and disrupting sleep[40]. Moreover, uncontrolled pain may adversely affect disease prognosis. The results of this meta-analysis indicate that music therapy can significantly alleviate pain in fracture patients, aligning with findings from numerous previous studies.

Mechanism of music therapy for pain relief: Music therapy is an effective non-pharmacological approach for pain relief. Physiologically, the melodies and rhythms of music, as forms of physical energy, stimulate the body through sound waves, generating resonance in muscles and organs and activating the pituitary gland to release endorphins. This process can inhibit pain-related neurotransmitter activity and promote the closure of the pain “gate”, thereby reducing the perception of pain[38]. Psychologically, music induces positive and uplifting emotions, evoking special emotional experiences that promote both mental and physical relaxation, which decreases patients’ sensitivity to pain[41]. The analgesic effects of music are likely mediated through multiple mechanisms. First, music stimulates the limbic system, which is closely associated with emotion, leading to endorphin release, regulation of the endocrine system, and improved circulation and respiration, collectively reducing pain perception[32]. Music therapy also inhibits activation of the adrenal sympathetic nervous system, lowering adrenaline and noradrenaline levels and suppressing cortisol secretion, further contributing to pain relief and enhancing patients’ sense of well-being[42]. Second, neuroimaging studies indicate that multiple brain regions involved in pain processing, including the striatum and the midbrain dopamine system, respond to music[43]. By activating these areas, music modulates pain perception and reduces discomfort. These findings suggest that clinicians can effectively incorporate music therapy into pain management strategies for fracture patients, providing both physiological and psychological benefits.

Comparison with other related studies: The findings of this study are consistent with those of previous research. For instance, Ortega et al[18] demonstrated that music therapy significantly reduces pain in patients with nasal bone fractures. Meng et al[44] provided a detailed exploration of the mechanisms through which music therapy alleviates pain, highlighting its role as an adjuvant intervention for postoperative fracture pain. Similarly, Li et al[21] reported that music therapy improved treatment compliance in children with elbow fractures while simultaneously reducing anxiety and pain. Other studies have shown that music can regulate emotions in patients undergoing fixed orthodontic treatment, helping them relax, divert attention, and decrease focus on discomfort, thereby alleviating procedural pain[45]. Collectively, these findings further support the conclusion of the present study: Music therapy is an effective non-pharmacological intervention for alleviating pain in patients with non-acute surgical fractures.

Recommendations for clinical application: Given the demonstrated efficacy of music therapy in pain management, it is recommended that clinicians integrate this intervention into standard pain management protocols for fracture patients. Music therapy not only alleviates pain but also enhances psychological well-being and supports rehabilitation outcomes. Consequently, its application may extend beyond fracture-related pain to other clinical conditions and symptoms, thereby broadening the scope and diversity of pain management strategies. Moreover, music therapy is relatively easy to implement, requiring minimal equipment and cost, which makes it a highly feasible and sustainable adjunct in clinical practice.

Although the present study focused on patients with non-acute fractures, music therapy may also offer benefits for alleviating anxiety and pain during the acute trauma phase. However, patients in the acute phase often experience more severe pain and psychological stress, which may require different intervention approaches and outcome measures. Investigating the application of music therapy in this context represents an important direction for future research.

The studies included in this review utilized a variety of musical genres, including classical music, light music, and natural sounds. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to recommend any single genre as superior. Individual musical preference may play a critical role in therapeutic efficacy, highlighting the need for future research on personalized music interventions.

First, clinical heterogeneity existed among the included patients. Fracture types varied widely, including limb, lower-limb, and nasal fractures, among others. In addition, participants differed in age and sex. Because this review focused on non-acute surgical fracture patients and music therapy is a highly specific intervention, all eligible participants were included, resulting in pronounced inter-patient variability. Second, the music therapy protocols themselves were heterogeneous. Intervention duration, frequency, and music selection differed across trials, with examples ranging from classical compositions and natural sounds to traditional Chinese pentatonic music. Finally, the included studies encompassed both Chinese- and English-language reports, introducing potential cultural variability in patients’ acceptance of and responsiveness to music therapy. This represents a limitation of the current meta-analysis. Future studies should aim to implement more standardized intervention protocols and reporting criteria to reduce heterogeneity and improve comparability across trials.

Most of the included studies are in Chinese, which indicates that music therapy is not widely applied to the treatment of anxiety in fracture patients abroad, and it is impossible to evaluate its curative effect more comprehensively. Therefore, the generalizability of our findings to other ethnic and cultural contexts may be limited and warrants further investigation. Moreover, the open nature of music therapy interventions makes it difficult to ensure blinding of both participants and practitioners, introducing potential performance bias. Additionally, the outcomes in most studies were predominantly psychological, with few objective physiological endpoints assessed.

Future research should incorporate blinded outcome assessments to reduce detection bias and develop standardized, culturally adapted music-intervention protocols to enhance credibility and applicability. Furthermore, investigations should examine the long-term effects of music therapy on objective clinical endpoints, such as fracture-healing rates and joint-function recovery, to better inform its clinical utility.

Expanding sample size and multicenter randomized controlled trials: Future research should expand sample sizes and conduct multicenter randomized controlled trials to comprehensively evaluate the therapeutic effects of music therapy on anxiety in patients with non-acute surgical fractures. Multicenter trials can reduce biases inherent in single-center studies, thereby enhancing the reliability and generalizability of findings. Larger sample sizes would allow for more precise estimation of the efficacy of music therapy and enable the identification of potential subgroup effects, such as variations in response based on gender, age, or cultural background.

Optimizing music intervention programs in combination with different cultural backgrounds: The effectiveness of music therapy may differ across cultural contexts. Future research should focus on optimizing music intervention programs to align with diverse cultural backgrounds, thereby facilitating broader application in localized clinical psychological care. For example, it would be valuable to investigate the role of traditional Chinese music in alleviating anxiety and depression, or to examine how music preferences across different cultures influence therapeutic outcomes. Designing culturally adapted interventions can enhance both the acceptability and efficacy of music therapy, ensuring that it meets the psychological needs of patients from varied cultural backgrounds.

In-depth study of the mechanisms of music therapy: Although initial studies have begun to elucidate the mechanisms underlying music therapy, many questions remain unanswered. Future research should investigate these mechanisms in greater depth and develop standardized intervention protocols to strengthen the evidence base for clinical practice. Advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography, could be employed to examine the effects of music therapy on brain activity and uncover its neurobiological pathways. Additionally, studies could explore the influence of music therapy on gene expression, neurotransmitter levels, immune function, and other physiological processes to provide a comprehensive understanding of its therapeutic mechanisms.

In conclusion, music therapy is an effective non-pharmacological adjunct for patients with non-acute surgical fractures. It can reduce anxiety, alleviate pain, and mitigate negative emotions such as depression, thereby supporting overall psychological well-being and enhancing rehabilitation outcomes. Future research should include larger sample sizes and multicenter randomized controlled trials to provide higher-quality evidence. Investigations examining the effects of music therapy on clinically meaningful functional endpoints, such as fracture-healing rates and joint function, are particularly warranted to further establish its therapeutic value in clinical practice.

We thank Yi Chen for his assistance with statistical analysis.

| 1. | Dong GL, Lan YP, Xu XF, Zheng QY, Chen HF. [Application and anesthetic effect of combined spinal-epidural anesthesia in fracture surgery]. Zhejiang Chuangshang Waike. 2023;28:2377-2379. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Chen JL, Luo R, Liu M. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and associated factors among geriatric orthopedic trauma inpatients: A cross-sectional study. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:919-928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wu JR, Wang QH, Xu T. [Clinical effect analysis of modified Tao Hong Si Wu Tang in treating limb swelling after tibial and fibular fracture surgery]. Xiandai Zhenduan Yu Zhiliao. 2023;34:3330-3332. |

| 4. | Zhou J, Ding H. [Clinical Analysis of Escitalopram Oxalate Combined with Compound Jieyu Decoction in Treatment of Adolescent Depression]. Liaoning Zhongyi Zazhi. 2024;51:80-84. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Ma MM. [Effect of Narrative Therapy on Psychological Nursing of Patients with Anxiety Disorder and Its Impact on HAMA and HAMD Scores]. Zhongguo Dianxing Bingli Daquan. 2025;1-7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Chen XX, Li SP. [Advances in Menopausal Syndrome-induced Anxiety State in Terms of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine]. Jiceng Zhongyiyao. 2024;3:104-109. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Chen YF, Chen ZZ. [Research progress on the effect of inhalation aromatherapy on anxiety in patients with surgery and physical diseases]. Zhongguo Dangdai Yiyao. 2024;31:184-188. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Zhang Y. [Application Value of EEG Biofeedback Apparatus in Patients with Anxiety Disorder]. Zhonguo Yiliao Qixie Xinxi. 2023;29:147-149. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Yang ZL, Chen CY, Xu LP. [Meta-analysis of the intervention effect of five-tone therapy on patients with post-stroke sleep disorders]. Quanke Huli. 2023;21:4629-4633. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Fu R, Liu Y. [Recent advance in the studies on music therapy in rehabilitation of neurodegenerative diseases]. Xinli Yuekan. 2022;208-212. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Bruscia KE. Standards of Integrity for Qualitative Music Therapy Research. J Music Ther. 1998;35:176-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Koelsch S, Vuust P, Friston K. Predictive Processes and the Peculiar Case of Music. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23:63-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fasano MC, Cabral J, Stevner A, Vuust P, Cantou P, Brattico E, Kringelbach ML. The early adolescent brain on music: Analysis of functional dynamics reveals engagement of orbitofrontal cortex reward system. Hum Brain Mapp. 2023;44:429-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Vern-Gross TZ, Shivnani AT, Chen K, Lee CM, Tward JD, MacDonald OK, Crane CH, Talamonti MS, Munoz LL, Small W Jr. Survival outcomes in resected extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: effect of adjuvant radiotherapy in a surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2011;81:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Humphrey P, Bennett C, Cramp F. The experiences of women receiving brachytherapy for cervical cancer: A systematic literature review. Radiography (Lond). 2018;24:396-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin CL, Hwang SL, Jiang P, Hsiung NH. Effect of Music Therapy on Pain After Orthopedic Surgery-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pain Pract. 2020;20:422-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 48675] [Article Influence: 2863.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 18. | Ortega A, Gauna F, Munoz D, Oberreuter G, Breinbauer HA, Carrasco L. Music Therapy for Pain and Anxiety Management in Nasal Bone Fracture Reduction: Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;161:613-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hu XL. [Application effect of music therapy based on the five tones and five colors in elderly patients with femoral trochanteric fracture, hypertension, and sleep disorders]. Dangdai Hushi (Shangxun Kan). 2022;29:118-122. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Bai PL, Zhou Q, Li L. [Effect of psychological nursing based on music therapy on postoperative rehabilitation training of elderly hip fracture patients]. Hainan Yixue. 2019;30:1623-1626. |

| 21. | Li TN, Wu HL, Yu Q, Xu SS. [The effect of visual music-guided intervention model on treatment compliance and emotion in children with elbow fracture]. Guoji Jingshenbingxue Zazhi. 2020;47:1079-1081,1085. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Huang B, Fang L. [Effect of music therapy on nerve block anesthesia in patients with hypertension and limb fracture]. Shezhi. 2023;35:85-89. |

| 23. | Xia JL, Wang J. [Application of visual music combined with animal-like sitcom video intervention in children patients with fractures]. Huli Shijian Yu Yanjiu. 2020;17:91-93. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Li CY, Xiao LL. [Application effect of psychological nursing combined with music therapy in patients with bone trauma]. Xinli Yuekan. 2021;16:138-139. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | Deng TF, Wang HZ, Chen JE, Ruan YT, Zhang LL. [Effect of visual music combined with induction nursing on treatment compliance and anxiety mood disorder in children patients with elbow frac-ture]. Huli Shijian Yu Yanjiu. 2019;16:67-69. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Ge XM, Deng MM, Zhu QM. [Effect analysis of music therapy on negative emotions in patients with lower limb fractures]. Zhonguo Yixue Zhuangbei. 2014;11. |

| 27. | Liu P, Liu LJ, Du KY, Liu T, Wu HN. [Music Therapy and its Application Study for Patients of Perioperative Period with Orbital Fractures]. Xiandai Shengwu Yixue Jinzhan. 2012;12:3913-3916. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Li L, Yang W. [Effect of Music Oxygen Bar on the Rehabilitation of Traumatic Pelvic Fracture Patients]. Kangfu Xuebao. 2018;28:54-58. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Lei L, Cao XQ, Yang F. [Clinical observation on perioperative pain and anxiety of hip fracture treated by TCM nursing intervention combined with Wuxing music]. Zhongguo Xiandai Yisheng. 2022;60:175-178. |

| 30. | Zhao Y, Dong QQ, Qin WK, Yan A, Zhang K, Zhao GD, Wang G, Geng JC, Wang ZF. [Multivariate Analysis of TCM Rehabilitation Effect of Distal Radius Fractures]. Zhongguo Zhongyi Jichu Yixue Zazhi. 2016;22:1511-1514. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Nilsson S, Kokinsky E, Nilsson U, Sidenvall B, Enskär K. School-aged children's experiences of postoperative music medicine on pain, distress, and anxiety. Paediatr Anaesth. 2009;19:1184-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mou QQ, Li JY. [Advances in the application of music therapy in cancer treatment]. Huli Yanjiu. 2017;31:529-533. |

| 33. | McKinney CH, Honig TJ. Health Outcomes of a Series of Bonny Method of Guided Imagery and Music Sessions: A Systematic Review. J Music Ther. 2017;54:1-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Aalbers S, Fusar-Poli L, Freeman RE, Spreen M, Ket JC, Vink AC, Maratos A, Crawford M, Chen XJ, Gold C. Music therapy for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD004517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhang Y, Li L, Chen J, Gao SH. [Exploration of the Origin of the Five Tone Therapy Thought in Inner Canon of Huangdi]. Liaoning Zhongyiyao Daxue Xuebao. 2024;26:1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 36. | Wu Q, Liu Z, Pang X, Cheng L. Efficacy of five-element music interventions in perinatal mental health and labor pain: A meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;40:101217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chen JR. [Mechanism of five-element music therapy in treating depression]. Zhongguo Yiyao Zhinan. 2018;16:177-178. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Li BB, Guan YX, Feng R, Wang XP, Zhao L, Liu J, Bian PL. [Impact of music therapy on fatigue, anxiety, and depression in patients with inflammatory bowel disease]. Huli Xuebao. 2019;26:65-68. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Zhou YX, Wu B. [Application of music therapy in geriatric medicine and its biological mechanisms]. Zhongguo Laonianxue Zazhi. 2019;39:2027-2030. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | Zhang WN, Zhang Y. [Qualitative experience of pain management after adult traumatic fracture surgery]. Quanke Huli. 2024;22:370-374. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 41. | Wang LJ. [Physiology, emotion, cognition, and behavior: A twenty-year study of music therapy in the management of chronic diseases in elderly Chinese]. Yinyue Tansuo. 2022;100-111. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 42. | Wang HL, Yang B, Wu BS. [Effect of low-temperature plasma ablation of the posterior cervical nerve branch on plasma β-endorphin, ACTH, and cortisol levels in patients with cervicogenic headache]. Zhongguo Shiyan Zhenduanxue. 2020;24:1821-1822. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Smith ML, Asada N, Malenka RC. Anterior cingulate inputs to nucleus accumbens control the social transfer of pain and analgesia. Science. 2021;371:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 54.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Meng HJ, Kong LJ, Deng YL, Han SL, Wang ZS, Li X, Zhang JL. [Research Progress of Music-assisted Therapy in Relieving Pain after Fracture Surgery]. Zhongguo Yixue Chuangxin. 2024;21:185-188. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 45. | Xu XM, Zhang LH, Jiang YH, Huang Y, Huang SH, Yang SW. [Clinical research of music in relieving orthodontic pain]. Huaxi Kouqiang Yixue Zazhi. 2013;31:365-368. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/