Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113473

Revised: November 3, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 160 Days and 11.7 Hours

Osteopathia striata with cranial stenosis (OSCS) is a rare genetic disorder (Men

Herein, we report the case of an 11-year-old girl with OSCS in association with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Osteopathia striata was suspected during the examination in a local healthcare facility due to arthritis. The patient was then transferred to the pediatric rheumatology clinic due to the inefficacy of the first-line systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Genetic analysis revealed a previously unreported AMER1 c.800C>A (p.Ser267*) variant, which was not detected in the healthy mother. Thus, the diagnosis of OSCS was made based on characteristic bone imaging and the presence of likely pathogenic AMER1 variant. This study presents the first detailed description of OSCS occurring in combination with JIA.

Diagnosis of OSCS can be challenging due to its rarity and phenotypic heterogeneity. The relationship between JIA and OSCS remains unclear. This case may raise awareness of OSCS.

Core Tip: This study presents the first detailed description of osteopathia striata with cranial stenosis (OSCS) occurring in conjunction with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). Arthritis may represent a manifestation of the underlying skeletal dysplasia, but the relationship between JIA and OSCS remains unclear. This case may contribute to raising awareness of OSCS and highlights the need for further research to explore potential associations between this rare skeletal disorder and autoimmune joint diseases such as JIA.

- Citation: Yakovlev AA, Gaidar EV, Suspitsin EN, Korzun PR, Kostik MM. Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis, associated with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A case report and review of literature. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 113473

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/113473.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113473

Osteopathia striata with cranial stenosis (OSCS), also known as Voorhoeve disease, is a rare genetic disorder (Mendelian Inheritance in Man: 300373) that is inherited in an X-linked dominant pattern[1-5]. It is classified as a form of skeletal dysplasia and is characterized by linear striations of bone sclerosis, primarily affecting the long bones. OSCS may present as a separate condition or as part of broader genetic syndromes such as Horan-Beighton syndrome and Goltz syndrome[6]. The estimated prevalence is approximately 0.1 per million population, with a female-to-male ratio of 2.5:1[7]. Approximately 100 cases have been described worldwide.

We present the first detailed description of OSCS occurring in association with juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA). JIA is the most common childhood rheumatic disease[8], while skeletal dysplasia can also often be accompanied by the development of joint involvement. The relationship between JIA and OSCS remains unclear. This case may contribute to raising awareness of OSCS and highlights the need for further research to explore potential associations between this rare skeletal disorder and autoimmune joint diseases such as JIA.

An 11-year-old Caucasian girl with JIA presented to the Pediatric Department with complaints of limping and ankle joint pain, despite the treatment with nonbiologic disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs.

In March 2022, a girl slipped and injured her left knee. A local traumatologist examined her, and a fracture was ruled out. Further evaluation revealed an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), and a watchful waiting approach was adopted. During the subsequent three months, the disease progression was observed: Swelling of the right knee and left ankle, and the development of limp, which led to hospitalization in the rheumatology department of a local healthcare facility. A comprehensive clinical and laboratory evaluation was performed. It revealed and elevated CRP: 47.19 mg/L (normal value < 5 mg/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate: 61 mm/hour (normal value < 20 mm/hour), rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody, anti-double stranded DNA antibodies: < 10 IU/mL were negative, and the antinuclear antibodies were positive 1/320 (normal value < 1/160) with a nucleolar pattern. Imaging studies were performed, including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left ankle, subtalar, and knee joints, as well as computed tomography (CT) scans of both knee joints. MRI findings revealed pronounced pes planus and signs of flexor tendon tendinitis of the foot. There was evidence of edema in the distal portion of the gastrocnemius muscle, bone marrow edema in the calcaneal apophysis, and the subcortical regions of the talus. MRI also showed altered signal intensity of the anterior cruciate ligament, likely due to stretching. Intra-articular alignment was preserved, and meniscal integrity was maintained. Moderate synovitis and edema of the synovial membrane were observed. CT of both knees confirmed bilateral synovitis. Additionally, bilateral alterations in bone architecture were observed, which may be consistent with striated osteopathy.

Based on the overall clinical, laboratory, and imaging findings, a diagnosis of JIA was established. During hospitalization, intra-articular glucocorticoid injections were administered into the right and left knee joints, accompanied by methotrexate therapy at a weekly dose of 12.5 mg. Nevertheless, the patient’s specific phenotypic characteristics ne

Past medical history was unremarkable.

Legally authorized representative (mother) denied any family history of genetic disorders. However, it is important to note that the girl exhibits phenotypic features similar to those observed in her half-brother.

On physical examination, vital signs were as follows: Body temperature: 36.6 °C, blood pressure: 116/65 mmHg, heart rate: 85 beats per minute, weight: 38 kg, height: 145 cm, body surface area: 1.2 m2.

General condition was satisfactory; overall well-being was good. The child displayed certain dysmorphic features, including a high forehead, closely spaced eyes, and malocclusion. The patient was noted to be shy. The child behaved in accordance with his age, and according to his legal representative, there were no behavioral peculiarities; therefore, specialized scales for assessing intellectual development were not used. Skin was clean, moderately moist, with reticular livedo. No peripheral edema was detected. Mucous membranes were clean and moist. No signs of upper respiratory tract inflammation were observed. The oropharynx was pink. Peripheral lymph nodes were not enlarged and were non-tender. The tongue was clean and not coated. Vesicular breath sounds were heard bilaterally and evenly throughout all lung fields; no rales were detected. Heart sounds were clear, rhythmic, and distinct. The abdomen was soft and non-tender on palpation in all regions. The liver was palpable along the costal margin. The spleen was not palpable. Stool: Normal in consistency. Urination was adequate.

Joint status was also assessed. The right knee joint showed minimal deformation and was not warm to the touch; the range of motion was full and painless. No signs of inflammation were noted in other joints. A complete, painless range of motion was preserved throughout. Furthermore, left-sided scoliosis (grade 2-3) was found. It should also be noted that the skull had a hydrocephalic configuration; the venous pattern was not prominently expressed.

A comprehensive laboratory examination was performed. The results of the complete blood count and extended biochemical analysis including protein fractions: Albumin, alpha-1, alpha-2, beta-1, beta-2, gamma; serum levels of albumin, alpha-1, alpha-2, beta-1, beta-2, and gamma globulins; urea, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, total protein, glucose, alkaline phosphatase, C-reactive protein, antistreptolysin-O, uric acid, and RF, as well as immunoglobulin A, M, and G levels, were within reference ranges. However, a borderline positive ANA titer was detected (1/160). Furthermore, to rule out metabolic disorders, a series of specialized biochemical tests was performed, including electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry and enzymatic diagnostics. All enzyme activities were within re

| Enzyme | Activity (μmol/L/hour) | Reference range (μmol/L/hour) |

| Galactocerebrosidase | 3.34 | 0.70-10.00 |

| α-glucosidase | 7.97 | 1.00-25.00 |

| α-galactosidase | 4.50 | 0.80-15.00 |

| β-glucocerebrosidase | 8.63 | 1.50-25.00 |

| Sphingomyelinase | 4.37 | 1.50-25.00 |

| α-iduronidase | 6.76 | 1.00-25.00 |

| Enzyme (associated disorder) | Activity (μmol/L/hour) | Reference range (μmol/L/hour) |

| N-acetyl-α-D-glucosaminidase (MPS IIIB) | 5.41 | 1-20 |

| Acetylgalactosamine-6-sulfatase (MPS IVA) | 1.83 | 0.5-10 |

| Arylsulfatase B (MPS VI) | 2.95 | 1-15 |

| β-D-galactosidase (GM1 gangliosidosis, MPS IVB) | 8.57 | 2-30 |

| β-D-glucuronidase (MPS VII) | 33.69 | 10-65 |

| Iduronate-2-sulfatase (MPS II) | 16.31 | 10-50 |

| Tripeptidyl peptidase 1 (neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis type 2, CLN2) | 58.05 | 15-85 |

Additionally, to clarify the nature of arthritis, an analysis of the intra-articular fluid was performed, revealing inflammatory changes characteristic of JIA. The results are reported in Table 3.

| Parameter | Unit | Result |

| Volume | mL | 1 |

| Color | - | Light yellow |

| Clarity | - | Slightly turbid |

| Protein | g/L | 19.00 |

| Native preparation (unstained) | ||

| Leukocytes | per HPF | 6-8-10 |

| Erythrocytes (fresh) | per HPF | 2-4 |

| Ragocytes | % | 15 |

| Stained preparation | ||

| Neutrophils | % | 17 |

| Lymphocytes | % | 60 |

| Macrophages | % | 2 |

| Other findings | ||

| Macrophages are morphologically similar to blood monocytes | - | 21 |

| Acid-fast bacilli | - | Not detected |

A comprehensive examination was conducted, including ultrasound studies. Abdominal and renal ultrasound did not reveal any abnormalities. Ultrasound examination of the joints revealed mildly expressed synovitis in both shoulder joints, both wrist joints, and the metacarpophalangeal joints of the hands. Additionally, exudative-proliferative synovitis with ultrasound signs of active inflammation was detected in the left elbow, right knee, and left ankle joint. Ultrasound signs of Achilles bursitis were also identified on the left side.

A radiographic examination of the thoracic and lumbar spine was performed in anteroposterior and lateral projections. The images revealed an S-shaped deformity in the frontal plane, with a right-sided thoracic curve peaking at Th5. The curvature angle between Th3 and Th7 measures 13 degrees according to Cobb’s method. There is also a left-sided thoracolumbar curve with the apex at Th12, and the deformity angle between Th8 and L4 measures 21 degrees (Cobb angle). Vertebral body rotation is observed: Grade 1 in the thoracic spine and grades 2-3 in the lumbar spine. Thoracic kyphosis is flattened, while lumbar lordosis is preserved. The height and structure of the vertebral bodies remain unchanged.

Whole-body MRI, targeted MRI of the left ankle joint, and, due to complaints of hearing loss, brain MRI following consultation with an audiologist were also performed. Whole-body MRI was performed using a standard protocol. Images were obtained in coronal projection using T2-weighted imaging, short tau inversion recovery, and diffusion-weighted whole-body imaging with background body signal suppression sequences with a slice thickness of 6.0/1.0 mm, as well as T1-weighted imaging in sagittal projection. A small fluid accumulation was observed in both elbow joints (minimal on the right, moderate on the left), a small amount of fluid in the hip and knee joints, and a moderate amount of effusion in both ankle joints, more pronounced on the left. An S-shaped scoliotic deformity of the thoracic spine was noted. No areas of increased magnetic resonance signal were detected in the visualized bones. The abdominal and pleural cavities, brain, and spine segments within the scan area showed no significant pathological changes. The visualized muscles exhibited typical signal characteristics and maintained their structure.

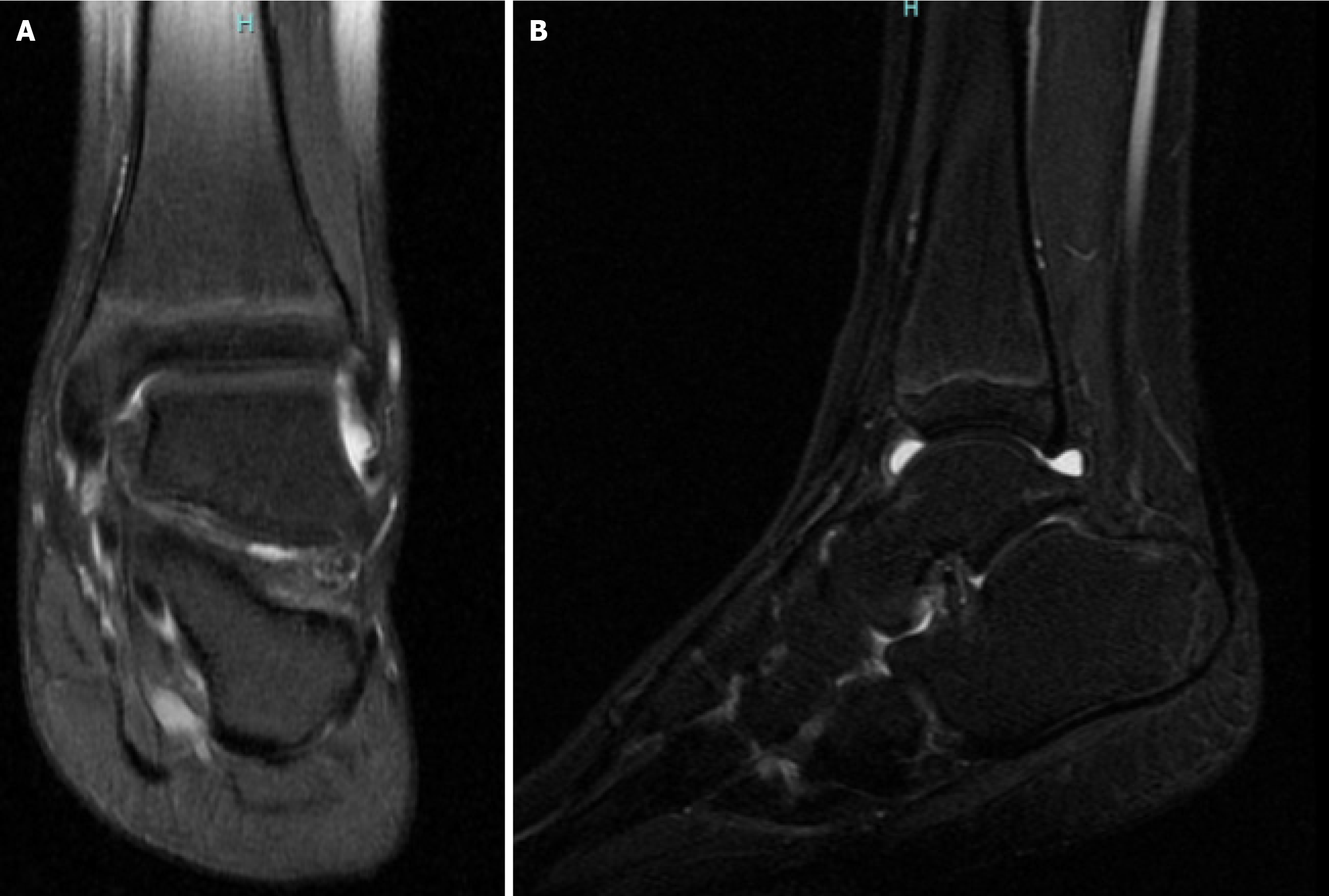

MRI of the left foot and ankle joint was performed using a dedicated coil (Figure 1). Images were obtained in three mutually perpendicular planes using proton density -weighted, T1-weighted, T2-weighted, and fat-suppressed sequences. Joint alignment in the ankle and visualized foot joints is preserved, with congruent articular surfaces. The shape and size of the visualized bones are normal. The cortical bone plates are intact. Articular cartilage is continuous and not thinned. In the distal metaphysis and diaphysis of the tibia, longitudinal striations are seen, corresponding to hypointense lines across all imaging sequences. Similar changes in the fibula and the first metatarsal bone cannot be excluded. Otherwise, the bone marrow signal is preserved, with no evidence of bone marrow edema. Fluid accumulation is observed in the ankle, subtalar, and talonavicular joints, without signs of synovial membrane thickening. Trace joint effusion is present in the remaining visualized joints. Fluid collections are also seen along the course of the posterior tibial tendon and the tendons of the flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus muscles. The periarticular soft tissues show no signs of edema or infiltration. These findings are consistent with synovitis of the left ankle, subtalar, and talonavicular joints, as well as tenosynovitis involving the posterior tibial tendon and the flexor tendons of the toes. The striated pattern observed in the tibia, and possibly in the fibula and first metatarsal bone, may correspond to striated osteopathy.

To further characterize the nature of the bone abnormalities, a series of imaging studies was performed, including radiography of the lower limbs, cranial radiographs (in both anteroposterior and lateral views), and CT. Radiographs of the lower limbs revealed vertical striations in the metaphyseal regions of the femoral and tibial bones (Figure 2). These changes were confirmed by a CT scan (Figure 3).

MRI of the brain was performed according to a standard protocol, with images acquired in three orthogonal planes (T1-weighted, T2-weighted, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery, and diffusion-weighted imaging sequences), allowing for evaluation of both supra- and infratentorial structures. The imaging revealed a space-occupying lesion in the right ambient cistern, containing a high amount of fat tissue. The differential diagnosis includes an intracranial lipoma vs a dermoid cyst. Additional findings included triventricular compensatory hydrocephalus, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, and hyperostosis of the cranial vault bones. A follow-up brain MRI was recommended for dynamic obser

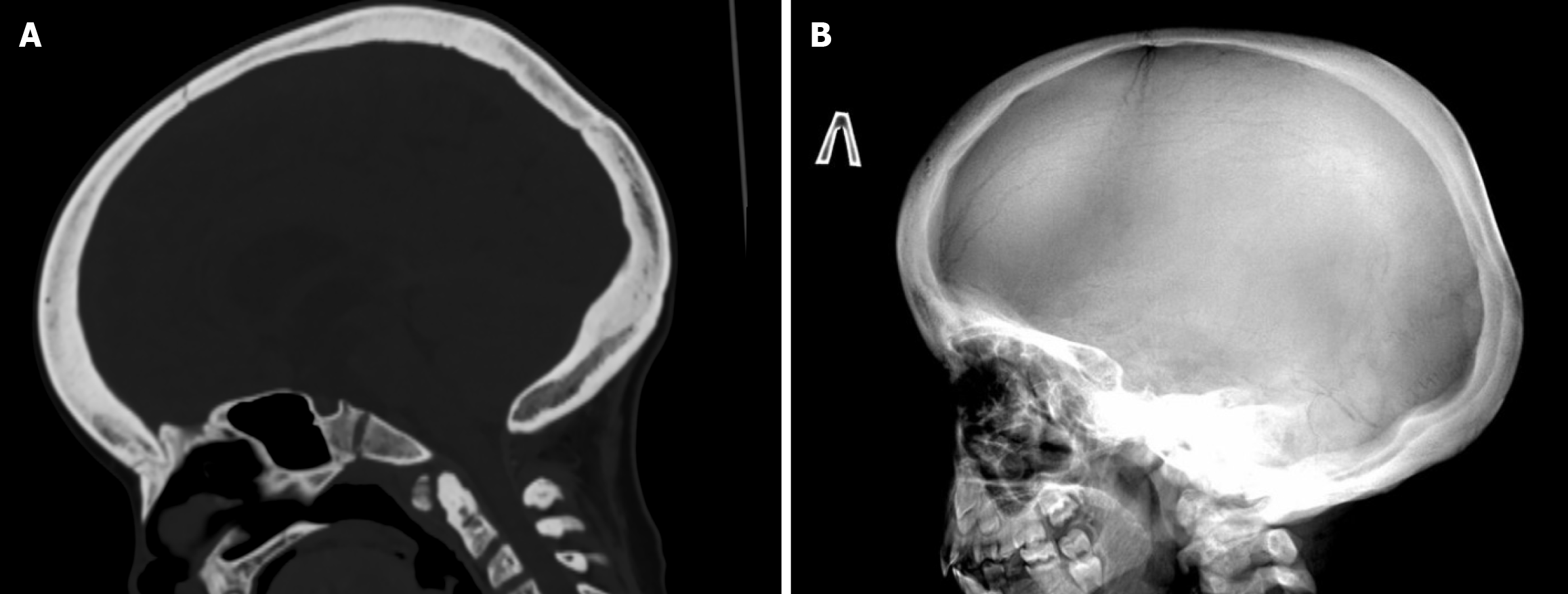

Due to the abnormalities detected on the brain MRI, a multispiral CT scan of the brain was performed. The findings were suggestive of striped osteopathy with cranial sclerosis (Figure 5). Additionally, non-union of the anterior and posterior arches of the C1 vertebra was identified.

Due to the presence of multiple coexisting conditions, the patient was evaluated by an audiologist, neurosurgeon, and ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologic consultation revealed no pathology; there were no signs of uveitis, and the fundus appeared normal. Since hearing loss is characteristic of striated osteopathy, an audiologist consultation was conducted. During the examination, tympanometry at 226 Hz was performed, showing type “A” tympanograms in both ears. Transient evoked otoacoustic emissions were not detected in either ear. Pure-tone audiometry revealed conductive hearing loss of a mild degree (grade 1) at speech frequencies in the right ear, while hearing in the left ear was within normal limits at these frequencies. Unilateral mild conductive hearing loss on the right side with normal hearing in the opposite ear was first found. During the neurosurgical consultation, no signs of compression of adjacent structures or evidence of malignancy were found. Tri-ventricular compensatory hydrocephalus, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, hyperostosis of the cranial vault bones, and sclerotic changes of the cervical vertebrae were noted.

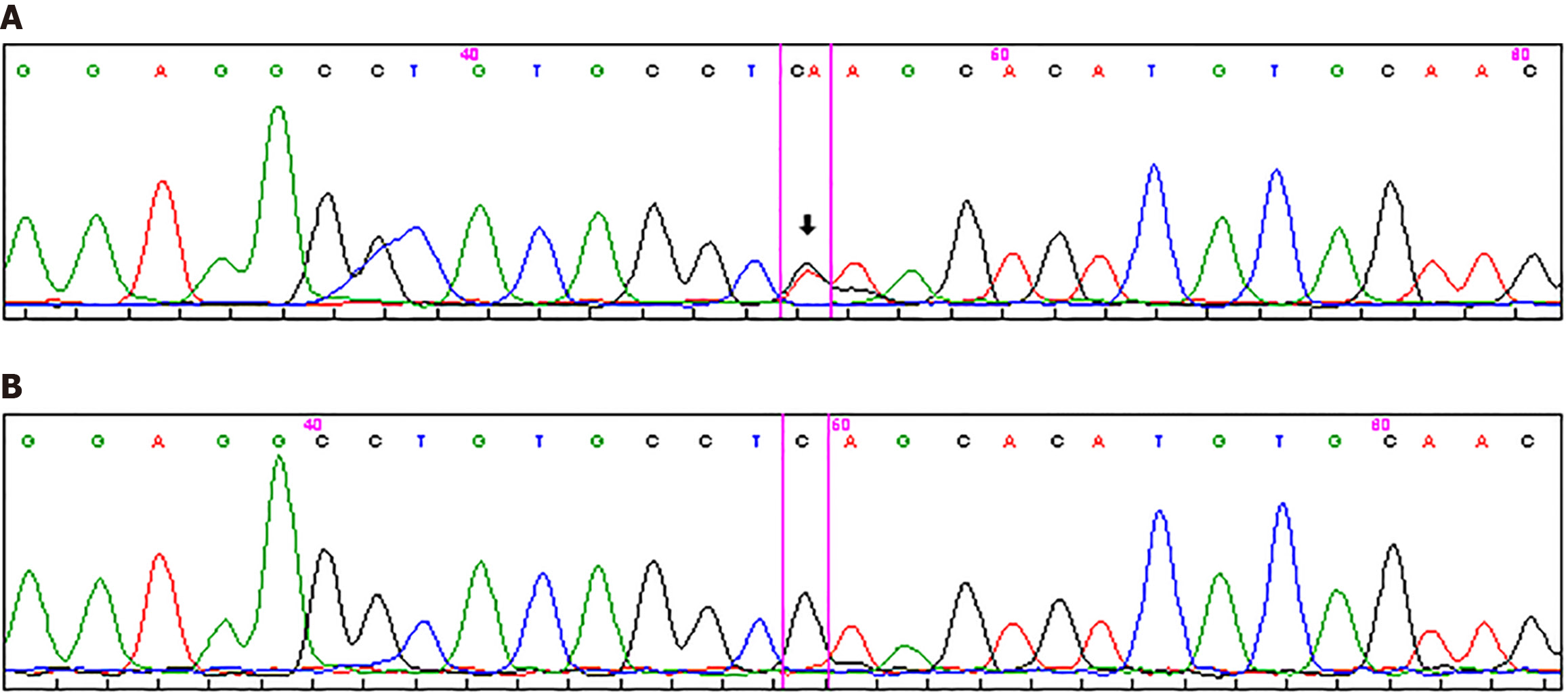

Sanger sequencing of the whole coding region of the AMER1/WTX gene (OMIM *300647) was performed in the proband using Beckman Coulter CEQ 8000 Genetic Analysis System according to the manufacturers’ protocol. A previously undescribed heterozygous nonsense variant, AMER1 NM_152424.4 с.800C>A (p.Ser267*), was identified (Figure 6). PCR amplification using self-designed primers (forward: 5’-GTCACATCCCCAAACAAGAGG-3’; reverse: 5’-ACCAGAACC TTCTCCACCAG-3’) followed by Sanger sequencing was performed to verify the identified variant in probands’ healthy mother: The variant was absent in her blood DNA.

Segregation analysis was not performed because other family members except patients’ mother declined further investigations. Considering the absence of the variant in the mother and the molecular nature of the change [loss-of-function (LoF) nonsense variant in a gene where LoF is a known disease mechanism], the AMER1 c.800C>A (p.Ser267*) variant is most likely a disease-causing mutation. According to the ACMG/AMP 2015 guidelines, this variant meets the criteria PVS1 (very strong; predicted loss-of-function) and PM2 (moderate; absent from population databases) and is therefore classified as likely pathogenic.

Combined with the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was JIA, RF-negative polyarthritis with OSCS, right-sided conductive hearing loss (grade 1), and idiopathic scoliosis (grade II-III).

Due to the presence of active arthritis, a decision was made to perform intra-articular corticosteroid injections. DMARD therapy with methotrexate was continued. As there are currently no established treatments for striated osteopathy, dynamic follow-up was recommended.

The patient continued to be followed up over time. The girl was hospitalized three more times for dynamic observation and comprehensive evaluation. No significant progression of JIA was observed, and methotrexate therapy was continued with dose adjustments based on body surface area. However, there was a noted progression of both scoliosis and hearing loss. Two years later, the patient was diagnosed with bilateral conductive hearing loss (grade II on the right, grade I on the left).

This study describes a patient with a rare genetic disorder, OSCS, as an incidental finding. In addition, the patient has joint damage, so it is not clear whether this is a result of her genetic disorder or underlying juvenile arthritis. The connection between JIA and the genetic disease remains unknown. It is possible that the arthritis was a component of skeletal dysplasia.

Little is known about the etiology and pathogenesis of this condition due to its rarity. However, genetic studies have identified pathogenic variants in the AMER1 gene (Xq11), also known as WXP or FAM123B, as underlying the patho

Aberrant activation of the WNT pathway is believed to contribute to the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases. However, direct evidence linking Wnt signaling in hematopoietic stem cell regulation to autoimmunity is limited. Growing evidence now supports WNT pathway involvement in major autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid ar

The WNT pathway plays a crucial role in T cell development and differentiation[18]. It provides essential proliferative signals to immature T cells, as shown in mice lacking the WNT-responsive transcription factors TCF1 or LEF1, which exhibit defective T and B cell maturation[18]. The canonical WNT/β-catenin/TCF pathway regulates T cell differentiation in both the thymus and peripheral lymphoid tissues, and its disruption can result in autoimmunity or immunodeficiency. Transcriptomic studies in rheumatoid arthritis have revealed the aberrant regulation of STAT3 and WNT signaling in CD4+ T cells[19]. Moreover, WNT-mediated stabilization of β-catenin enhances the survival of CD4+/CD25+ regulatory T cells, helping prevent inflammation. However, under inflammatory conditions, excessive WNT activation may sup

B cells mediate humoral immunity through the production of antibodies, opsonization, and complement activation. Wnt signaling is essential for the differentiation of hematopoietic stem cells into functional B cells. Although Wnt regulation of T cell development is well established, its role in B cell biology remains less explored. Nevertheless, several studies indicate that aberrant Wnt activity in B cells is associated with autoimmune responses[17].

It is well established that the pathogenesis of JIA involves a loss of immunological tolerance with activation of both T- and B-cell immune responses[21]. One proposed mechanism is reduced sensitivity to regulatory T-cell control[22]. Accordingly, dysregulation of the Wnt signaling pathway may increase susceptibility to autoimmune triggers and fa

The clinical phenotype is variable but includes several distinctive features, such as[7,12,13,23-27]: Macrocephaly; headaches; facial nerve palsy caused by narrowing of cranial foramina and sclerosis of the skull base and vault; con

In the study, these distinctive phenotypic features are also described. In males, the disease tends to progress more severely. Affected boys most often die during the perinatal period. Among those who survive, osteosclerosis without metaphyseal striations may be observed, along with congenital anomalies of the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems, as well as features typical of affected females. In males with somatic mosaicism for loss-of-function AMER1 variants or in those with Klinefelter syndrome (47, XXY), phenotypes similar to those seen in female heterozygotes have been reported[28].

Other manifestations may also be present, including sternal deformities, cataracts, and congenital anomalies of the heart, kidneys, and gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, this condition is characterized by distinctive craniofacial features, such as: (1) Cleft lip and/or palate; (2) High-arched palate; (3) A narrow maxilla; (4) Malocclusion; (5) Bifid uvula; (6) Microdontia; (7) Retained teeth; and (8) A dense mandible with visible striations.

Furthermore, reports have described shortened and deformed dental roots, temporomandibular joint ankylosis, midface hypoplasia, and associations with the Pierre-Robin sequence[7,12,13,16,23,27]. Table 4 presents a comparison table of the case with previous OSCS cases.

| OSCS | OSCS and JIA |

| Macrocephaly | Inflammatory changes in synovial fluid |

| Facial nerve palsy caused by narrowing of cranial foramina and sclerosis of the skull base and vault | Arthritis |

| Conductive hearing loss | Age of onset < 16 years |

| Sclerosis of the facial bones and the mastoid region | Erosions, periostitis, growth disturbance |

| Hypertelorism | Joint-space narrowing, erosions, periarticular osteopenia |

| High forehead with prominent frontal tuberosities | Occasionally TMJ arthritis causing mandibular hypoplasia; otherwise, rare |

| Broad, depressed nasal bridge | |

| Clubfoot | |

| Spina bifida | |

| Varying degrees of intellectual disability | |

| Striated pattern in long tubular bones or sandwich-vertebrae |

The diagnosis of OSCS is established in female probands based on the presence of characteristic clinical features and the identification of a heterozygous pathogenic variant in the AMER1 gene through molecular genetic testing. In male probands, the diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of typical features and the detection of a hemizygous pathogenic variant in the AMER1 gene via molecular analysis[28]. The variant detected in our patient leads to premature protein termination; such a truncating events are commonly described in OSCS patients[29,30].

The condition is most often suspected based on findings from imaging studies, such as conventional radiography. MRI and CT can provide a more detailed assessment of bone structure, thereby supporting the diagnosis.

Due to the variable phenotype, the prognosis of the disorder depends on the severity of clinical manifestations. In males, the disease typically progresses more severely. In most cases, affected males do not survive the perinatal period; however, some survivors may present with osteosclerosis (without metaphyseal striations) and congenital malformations of the cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, and genitourinary systems. These features may coexist with manifestations typically observed in affected females, including variable skeletal anomalies.

Thus, our study describes the first case of OSCS in association with JIA. One of the primary questions of the study was whether arthritis is a component of skeletal dysplasia or whether the patient suffers from two separate conditions. The presence of inflammatory changes in the synovial fluid suggests that these are two distinct pathological entities. Thus, this is also the first description that characterizes joint involvement in a patient with OSCS not as part of bone pathology, but as a feature of JIA.

The relationship between JIA and OSCS remains unclear. While the observed arthritis may be part of the broader skeletal dysplasia, the presence of inflammatory changes in synovial fluid supports the hypothesis that these are two distinct conditions co-occurring in the same patient. This case highlights the importance of recognizing rare genetic disorders in the differential diagnosis of JIA. It may contribute to a better understanding of potential overlaps and distinctions between inflammatory and dysplastic skeletal pathologies.

| 1. | Joseph DJ, Ichikawa S, Econs MJ. Mosaicism in osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1506-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jeong C, Kim M, Yim J, Park IJ, Lee J, Lee J. Novel WTX nonsense mutation in a family diagnosed with osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis: Case report. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arora V, Bijarnia-Mahay S, Saxena KK, Suman P, Kukreja S. Osteopathia Striata with Cranial Sclerosis: A Face-to-Radiograph-to-Gene Diagnosis. J Pediatr Genet. 2022;11:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Behninger C, Rott HD. Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis: literature reappraisal argues for X-linked inheritance. Genet Couns. 2000;11:157-167. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Rott HD, Krieg P, Rütschle H, Kraus C. Multiple malformations in a male and maternal osteopathia strata with cranial sclerosis (OSCS). Genet Couns. 2003;14:281-288. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Jagtap R, Garrido MB, Hansen M. Osteopathia striata in the mandible with cranial sclerosis: a case report and review of the literature. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2021;47:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Berenholz L, Lippy W, Harrell M. Conductive hearing loss in osteopathia striata-cranial sclerosis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:124-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ravelli A, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet. 2007;369:767-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 983] [Cited by in RCA: 1103] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Major MB, Camp ND, Berndt JD, Yi X, Goldenberg SJ, Hubbert C, Biechele TL, Gingras AC, Zheng N, Maccoss MJ, Angers S, Moon RT. Wilms tumor suppressor WTX negatively regulates WNT/beta-catenin signaling. Science. 2007;316:1043-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Maeda K, Kobayashi Y, Koide M, Uehara S, Okamoto M, Ishihara A, Kayama T, Saito M, Marumo K. The Regulation of Bone Metabolism and Disorders by Wnt Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hu L, Chen W, Qian A, Li YP. Wnt/β-catenin signaling components and mechanisms in bone formation, homeostasis, and disease. Bone Res. 2024;12:39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ward LM, Rauch F, Travers R, Roy M, Montes J, Chabot G, Glorieux FH. Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis: clinical, radiological, and bone histological findings in an adolescent girl. Am J Med Genet A. 2004;129A:8-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ng DW. A Case Study of a Preadolescent With Osteopathia Striata With Cranial Sclerosis. J Pediatr Health Care. 2017;31:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Enomoto Y, Tsurusaki Y, Harada N, Aida N, Kurosawa K. Novel AMER1 frameshift mutation in a girl with osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2018;58:145-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | O'Byrne JJ, Phelan E, Steenackers E, van Hul W, Reardon W. Germline mosaicism in osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis--recurrence in siblings. Clin Dysmorphol. 2016;25:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Goodman JR, Robertson CU. Osteopathia striata--a case report. Int J Paediatr Dent. 1993;3:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi J, Chi S, Xue J, Yang J, Li F, Liu X. Emerging Role and Therapeutic Implication of Wnt Signaling Pathways in Autoimmune Diseases. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:9392132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Staal FJ, Luis TC, Tiemessen MM. WNT signalling in the immune system: WNT is spreading its wings. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:581-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 461] [Cited by in RCA: 459] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ye H, Zhang J, Wang J, Gao Y, Du Y, Li C, Deng M, Guo J, Li Z. CD4 T-cell transcriptome analysis reveals aberrant regulation of STAT3 and Wnt signaling pathways in rheumatoid arthritis: evidence from a case-control study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2015;17:76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ding Y, Shen S, Lino AC, Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. Beta-catenin stabilization extends regulatory T cell survival and induces anergy in nonregulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yakovlev AA, Nikitina TN, Kostik MM. Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Associated Uveitis. Current Status: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Clinical Issues. Curr Pediatr. 2025;23:424-437. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wehrens EJ, Mijnheer G, Duurland CL, Klein M, Meerding J, van Loosdregt J, de Jager W, Sawitzki B, Coffer PJ, Vastert B, Prakken BJ, van Wijk F. Functional human regulatory T cells fail to control autoimmune inflammation due to PKB/c-akt hyperactivation in effector cells. Blood. 2011;118:3538-3548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Koudstaal MJ, Wolvius EB, Ongkosuwito EM, van der Wal KG. Surgically assisted rapid maxillary expansion in two cases of osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2008;45:337-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zicari AM, Tarani L, Perotti D, Papetti L, Nicita F, Liberati N, Spalice A, Salvatori G, Guaraldi F, Duse M. WTX R353X mutation in a family with osteopathia striata and cranial sclerosis (OS-CS): case report and literature review of the disease clinical, genetic and radiological features. Ital J Pediatr. 2012;38:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lüerssen K, Ptok M. Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis and hearing loss. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lazar CM, Braunstein EM, Econs MJ. Clinical vignette: osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:152-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Daley TD, Wysocki GP, Bohay RN. Osteopathia striata, short stature, cataracts, and microdontia: a new syndrome? A case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Holman SK, Daniel P, Jenkins ZA, Herron RL, Morgan T, Savarirayan R, Chow CW, Bohring A, Mosel A, Lacombe D, Steiner B, Schmitt-Mechelke T, Schroter B, Raas-Rothschild A, Miñaur SG, Porteous M, Parker M, Quarrell O, Tapon D, Cormier-Daire V, Mansour S, Nash R, Bindoff LA, Fiskerstrand T, Robertson SP. The male phenotype in osteopathia striata congenita with cranial sclerosis. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:2397-2408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jenkins ZA, van Kogelenberg M, Morgan T, Jeffs A, Fukuzawa R, Pearl E, Thaller C, Hing AV, Porteous ME, Garcia-Miñaur S, Bohring A, Lacombe D, Stewart F, Fiskerstrand T, Bindoff L, Berland S, Adès LC, Tchan M, David A, Wilson LC, Hennekam RC, Donnai D, Mansour S, Cormier-Daire V, Robertson SP. Germline mutations in WTX cause a sclerosing skeletal dysplasia but do not predispose to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:95-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Perdu B, de Freitas F, Frints SG, Schouten M, Schrander-Stumpel C, Barbosa M, Pinto-Basto J, Reis-Lima M, de Vernejoul MC, Becker K, Freckmann ML, Keymolen K, Haan E, Savarirayan R, Koenig R, Zabel B, Vanhoenacker FM, Van Hul W. Osteopathia striata with cranial sclerosis owing to WTX gene defect. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:82-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/