Published online Feb 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113461

Revised: October 5, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: February 18, 2026

Processing time: 162 Days and 13.3 Hours

Research productivity is a cornerstone of academic medicine, driving evidence-based practice, innovation, and professional advancement. In surgical specialties such as orthopedics, active research engagement is essential to improving patient outcomes and advancing clinical techniques. However, despite notable progress in Saudi Arabia’s medical research landscape, orthopedic research output remains limited and concentrated within a few institutions. Understanding the barriers that hinder orthopedic surgeons from conducting research is therefore crucial to strengthening national research capacity and aligning with Saudi Vision 2030’s goal of fostering scientific excellence.

To identify the barriers that limit research productivity among orthopedic sur

We used a descriptive, cross-sectional, quantitative design, employing a stru

A total of 105 orthopedic surgeons completed the survey. A statistically significant association was found between prior research experience and having served as a primary investigator within the past 5 years. Additionally, a highly significant association was found with co-authorship in the last 5 years (P < 0.001), as 52 participants (55.3%) had contributed as co-authors at least once. However, there was no significant association between prior research experience and factors such as allocated research time (P = 0.280), level of practice (P = 0.147), years in practice (P = 0.826), or the number of patients seen per week (P = 0.885). Univariate analysis revealed several barriers to research productivity: (1) Insufficient research time (71; 67.6%); (2) Lack of research assistants (57; 54.3%); (3) Inadequate research training (48; 45.7%); (4) Lack of funding (42; 40%); (5) Lack of research collaboration (39; 37.1%); (6) Lack of reward/incentive (38; 36.2%); and (7) No personal interest (20; 19.04%).

Addressing protected time, support staff, and research training may enhance orthopedic research productivity. This study highlights key institutional and educational gaps that can guide policy reforms and strengthen national orthopedic research capacity.

Core Tip: Research productivity among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia remains limited due to restricted research time, insufficient support staff, and a lack of formal research training. This cross-sectional study highlights the key barriers and motivations influencing research engagement across various practice levels. Addressing these institutional and educational gaps is essential to strengthening orthopedic research capacity and enhancing national academic output.

- Citation: Alaseem A, Alhomaidhi S, Aljudi S, Albishi W. Barriers to orthopedic surgery research productivity in Saudi Arabia. World J Orthop 2026; 17(2): 113461

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i2/113461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i2.113461

Research is one of the foundational pillars of academic medicine, alongside education and clinical practice, and plays a critical role in advancing medical knowledge and patient care. Academic institutions are often evaluated using both qualitative and quantitative indicators of research performance, with publication output serving as a primary benchmark of institutional productivity and scientific credibility[1,2]. Faculty members with strong research output often benefit from professional recognition, academic promotions, and career advancement opportunities[3,4].

Motivators such as financial rewards and promotions, research interest and the potential to improve patient care often drive faculty members to participate in research[5,6]. However, studies from Saudi Arabia have reported several barriers that can prevent an institute’s faculty members from conducting scientific research, including limited research time, lack of funding, and insufficient research support, such as statistical expertise or mentorship[2,7-10]. In more advanced stages of academic careers, institutional incentives often diminish, contributing to a notable decline in research productivity[3].

Barriers to conducting research have far-reaching consequences. They limit innovation, slow the translation of evidence into clinical practice, and reduce opportunities for professional development. Over time, these challenges may also lead to reduced publication quality, hindered institutional growth, and diminished international visibility for national research.

While it continues to increase in volume, Saudi Arabia’s orthopedic research output remains limited in terms of quality and global visibility. A recent bibliometric analysis revealed that a significant portion of the output is concentrated in a few academic centers and is predominantly published in lower-impact journals[11]. These findings suggest that Saudi health sciences research is on an upward trajectory, supported by an increase in publication output and international collaborations. The country has positioned itself as a leader in medical education and research within the Arab world[10,12]. However, regional studies still report gaps in research output among specific disciplines. For instance, orthopedic research across Arab countries has been described as underdeveloped, with critics pointing to systemic institutional limitations and a lack of research culture. This underdevelopment is also reflected in bibliometric analyses, which show a persistent underrepresentation of publications from Arab countries in Q1 orthopedic journals[13,14]. Despite efforts to expand medical research across the region, orthopedic research continues to face systemic limitations and a lack of sustained research culture[12].

The primary goal of this study was to identify barriers that limit research productivity among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia and to compare how these barriers differ across subspecialties, levels of practice, and institutional settings. Additionally, we aimed to explore the goals and motivations underlying research participation to gain a comprehensive understanding of orthopedic research engagement. We chose to study orthopedic surgeons because previous bibliometric studies have identified this specialty to be underrepresented in high-impact medical research despite its clinical and economic importance, making it an ideal group for examining research barriers.

Participants were recruited through professional networks, orthopedic surgery societies, and hospital affiliations via email and social media platforms, with informed consent obtained before participation. The study focused on licensed orthopedic surgeons actively practicing in Saudi Arabia, including consultants, specialists, fellows, and residents. It excluded undergraduates, students, and interns, as well as those not involved in clinical practice, such as retired sur

A convenience sampling approach was used, which is suitable for exploratory cross-sectional studies where participants meet predefined inclusion criteria[8]. The sample size was calculated using a standard formula for cross-sectional studies, assuming a 95% confidence interval (CI) level, 5% margin of error, and 50% expected prevalence, which yielded a minimum of 96 participants. A total of 105 surgeons completed the survey, exceeding this requirement. Data were collected using a self-developed, structured online questionnaire designed by the research team based on an extensive review of the literature and tailored to the Saudi orthopedic context.

The questionnaire was developed after reviewing relevant studies to identify the most commonly reported barriers to research productivity. The research team then drafted and refined items to capture both institutional and individual-level barriers. The survey was divided into three sections: (1) Demographics (for example, age, sex, level of practice, subspecialty, and patient load); (2) Research activities (for example, prior research experience, allocated time, and roles as a primary or co-author investigator); and (3) Barriers and goals (for example, insufficient time, lack of funding, and motivations for engaging in research). Respondents could select one or several options for questions concerning barriers and goals, but were eventually asked to choose the single most relevant one.

This study adhered to the principles of the Belmont report-respect for persons, beneficence, and justice. Participation was voluntary, informed consent was obtained electronically, and confidentiality was maintained by anonymizing all responses. To ensure rigor, the survey underwent expert validation by two orthopedic researchers to confirm content relevance and clarity. Reliability testing during pilot administration produced a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84, indicating good internal consistency.

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 21. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize categorical variables, while associations were examined using χ2 tests after verifying that as

A total of 105 orthopedic surgeons completed the survey. Most respondents were males (81.9%) and held clinical roles across a range of practice levels, with academic consultants and residents being the most represented groups. Over half of the participants worked in public hospitals, while others were affiliated with university or private institutions. Pediatric orthopedics and arthroplasty were the most frequently reported subspecialties. Detailed demographic and professional characteristics are presented in Table 1.

| Characteristics | n = 105 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 86 (81.9) |

| Female | 19 (18.1) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 38.5 ± 10.22 |

| Minimum | 24 |

| Maximum | 68 |

| Level of practice | |

| Resident | 27 (25.7) |

| Fellow | 13 (12.4) |

| Specialists | 12 (11.4) |

| Consultant (academic) | 28 (26.7) |

| Consultant (non-academic) | 25 (23.8) |

| Practice hospital | |

| University hospital | 50 (47.6) |

| Public hospital | 56 (53.3) |

| Private hospital/clinic | 28 (26.7) |

| Subspecialty | |

| Pediatric orthopedic | 24 (22.9) |

| Arthroplasty | 15 (14.3) |

| General orthopedic | 13 (12.4) |

| Orthopedic trauma | 12 (11.4) |

| Sport medicine | 11 (10.5) |

| Spine | 9 (8.6) |

| Upper extremity | 8 (7.6) |

| Foot and ankle | 6 (5.7) |

| Orthopedic oncology | 6 (5.7) |

| Deformity | 7 (6.7) |

| Years in practice | |

| < 5 | 43 (41) |

| 5-10 | 21 (20) |

| 11-20 | 23 (21.9) |

| > 20 | 18 (17.1) |

| Number of patients seen per week | |

| 1-20 | 25 (23.8) |

| 21-40 | 25 (23.8) |

| 41-60 | 30 (28.6) |

| > 60 | 25 (23.8) |

Most respondents (89.5%) had participated in at least one previous research project. About 41% had not practiced for more than 5 years after board certification. Additionally, 41% had no dedicated research time, and 59% had not acted as primary investigators in the past year. Most research publications were case reports (72.4%), retrospective studies (63.8%), and cross-sectional studies (44.8%). Further details on research experience and publication types are presented in Table 2.

| Research activity type | n = 105 |

| Any prior research work | 94 (89.5) |

| Allocated research time | |

| None | 43 (41) |

| < 10% | 43 (41) |

| 10%-50% | 19 (18.1) |

| Primary investigator in the last year | |

| None | 62 (59) |

| 1-4 | 38 (36.2) |

| > 5 | 5(4.8) |

| Primary investigator in the last 5 years | |

| None | 38 (36.2) |

| 1-4 | 46 (43.8) |

| ≥ 5 | 11 (10.5) |

| > 10 | 10 (9.5) |

| Co-author in the last year | |

| None | 36 (34.3) |

| 1-4 | 58 (55.2) |

| ≥ 5 | 11 (10.5) |

| Co-author in the last 5 years | |

| None | 17 (16.2) |

| 1-4 | 54 (51.4) |

| ≥ 5 | 34 (32.3) |

| Type of prior research study participation | |

| Randomized controlled trial | 8 (7.6) |

| Prospective cohort | 22 (21) |

| Retrospective | 67 (63.8) |

| Cross-sectional | 47 (44.8) |

| Case report | 76 (72.4) |

| Narrative review | 10 (9.5) |

| Systemic review | 25 (23.8) |

Wer identified a significant association with prior research experience, particularly in serving as a primary investigator within the past 5 years (P = 0.01), with 44 participants (46.8%) having held this role at least once. Additionally, a highly significant association was observed with co-authorship in the last 5 years (P < 0.0001), where 52 participants (55.3%) had contributed as co-authors at least once. However, there was no significant association between prior research experience and factors such as allocated research time (P = 0.280), level of practice (P = 0.147), years in practice (P = 0.826), or the number of patients seen per week (P = 0.885).

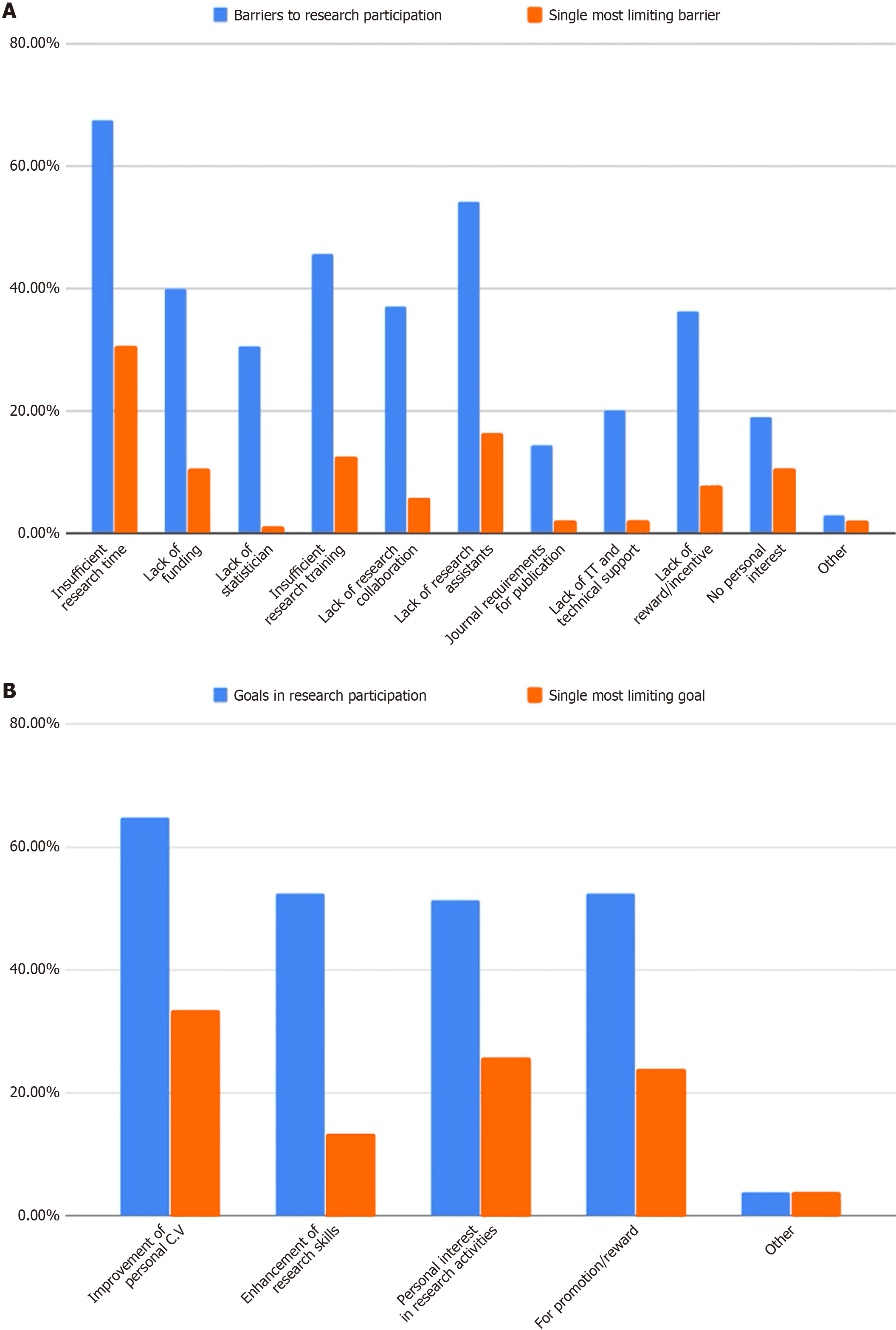

Multivariate analysis that considered all barriers was conducted, and the most selected barrier was insufficient research time (71; 67.7%), followed by the lack of research assistants (57; 54.3%) and inadequate research training (48; 45.7%). When the participants were asked to choose one single barrier as the most limiting, insufficient research time (32; 30.5%) followed by lack of research assistants (17; 16.2%) created the biggest barriers (Figure 1A).

When the respondents were asked about their goals for research participation, improving their personal curriculum vitae (CV) was the most chosen option (68; 64.8%). Enhancement of research skills and promotion/reward came in second, as reported by 55 (52.4%) each. When asked what single goal was the most important to them, improvement of personal CV for promotion/reward was the most important (35 (33.3%) and 25 (23.8%), respectively) (Figure 1B).

When barriers and goals to research participation were identified based on the level of practice, the most limiting barrier or single important goal based on the level of practice residents, non-academic consultants, registrars, and fellows chose insufficient research time as the single most limiting barrier to research participation 14 (43.8%), 7 (21.9%), 5 (15.6%), 3 (9.4%) respectively. Furthermore, the most important goal for research participation for residents and fellows was the improvement of personal CV 19 (54.3%) and 9 (25.7%), respectively, where academic consultants chose personal interest in research activities 13 (48.1%), nonacademic consultants chose for promotion/reward 8 (32%) (Table 3).

| Level of practice | Single most limiting barrier to research participation | Single most important goal for research participation | ||

| Resident | Insufficient research time | 14 (43.8) | Improvement of personal CV | 19 (54.3) |

| Fellow | Insufficient research time | 3 (9.4) | Improvement of personal CV | 9 (25.7) |

| Specialist | Insufficient research time | 5 (15.6) | Enhancement of research skills | 4 (28.6) |

| Consultant (academic) | Lack of research assistants | 11 (64.7) | Personal interest in research activities | 13 (48.1) |

| Consultant (non-academic) | Insufficient research time | 7 (21.9) | For promotion/reward | 8 (32) |

Finally, when barriers and goals to research participation were identified based on the respondents’ subspecialties, the most significant barrier to research was the lack of research assistants, particularly among arthroplasty surgeons (23.5%) and spine, oncology, upper extremity, and deformity surgeons (17.6% each). Regarding goals, general orthopedics, spine, and upper extremity surgeons prioritized personal research interest (14.8%), while pediatric orthopedics, sports medicine, orthopedic trauma, and deformity surgeons most valued promotion/reward as their primary goal (Table 4).

| Subspecialty | Single most limiting barrier to research participation | Single most important goal for research participation | ||

| General orthopedics | Insufficient research time | 5 (15.6) | Personal interest in research activities | 4 (14.8) |

| Pediatric orthopedics | Lack of funding | 4 (36.4) | For promotion/reward | 9 (36) |

| Spine | Lack of research assistants | 3 (17.6) | Personal interest in research activities | 4 (14.8) |

| Foot and ankle | Insufficient research time | 3 (9.4) | Improvement of personal curriculum vitae | 3 (8.6) |

| Orthopedic oncology | Lack of research assistants | 3 (17.6) | Personal interest in research activities | 3 (11.1) |

| Orthopedic trauma | Lack of research collaboration | 2 (33.3) | For promotion/reward | 5 (20) |

| Sports medicine | Lack of funding | 3 (27.3) | For promotion/reward | 6 (24) |

| Upper extremity | Lack of research assistants | 3 (17.6) | Personal interest in research activities | 4 (14.8) |

| Arthroplasty | Lack of research assistants | 4 (23.5) | Enhancement of research skills | 5 (35.7) |

| Deformity | Lack of research assistants | 3 (17.6) | For promotion/reward | 3 (12) |

Research plays a vital role in patient care and is highly valued because it provides various approaches that aid in informed decision-making. The main goal of this study was to identify the barriers that limit research productivity and the goals behind influencing research work among orthopedic surgeons. It also identified the major obstacles and challenges, allowing us to improve the research process from all aspects.

Most participants were interested and involved in research activities, but they faced multiple barriers. The participants were asked about all ten barriers, and the most frequently selected barrier was insufficient research time (71; 67.7%), followed by the lack of research assistants (57; 54.3%). These two barriers were each identified as the single most limiting barrier. Lack of funding, lack of statisticians, insufficient research training, lack of research collaboration, journal re

Contrary to our results, a multi-country study from Africa identified limited mentorship and inadequate funding as the most significant barriers to clinician-led research rather than insufficient time[8]. This contrast underscores how con

In this study, we identified multiple research participation goals, and the results showed that improving personal CV (68; 64.8%) was the most influential and the single most important goal. Enhancement of research skills and promotion/reward came in second with 55 (52.4%) each. Financial incentives, intrinsic interest in research, and the potential to improve patient outcomes were also essential motivators[6,11]. Conversely, time constraints were identified as the most common obstacle to research participation in several international studies[6,14].

Despite the various barriers reported by participants in our study, orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia are showing an increasing interest in research, as evidenced by the growing number of publications. Our study found that 94 (89.5%) respondents had participated in at least one research project during their careers. The most commonly published study designs were case reports (76; 72.4%), retrospective studies (67; 63.8%), and cross-sectional studies (47; 44.8%).

Bibliometric evidence shows that Saudi Arabia’s orthopedic research output remains largely clustered in certain institutions and published in lower-impact regional journals[11]. Moreover, there is a persistent underrepresentation of Arab authors in Q1 orthopedic journals, highlighting a systemic issue in both access and international research inte

Our study found a significant association between having conducted any previous research and being the primary investigator in the last 5 years, with 44 (46.8%) participants having held this role at least once. Additionally, 52 (55.3%) participants were co-authors at least once in the last 5 years, indicating a highly significant relationship. However, we did not identify a significant association between prior research and allocated research time, level of practice, years in practice, and number of patients seen weekly.

One of the most significant barrier to research was the lack of research assistants, particularly among arthroplasty surgeons (23.5%) and those in spine, oncology, upper extremity, and deformity subspecialties (17.6% each). In terms of research goals, general orthopedic surgeons, spine surgeons, and upper extremity surgeons prioritized personal research interest (14.8%), whereas pediatric orthopedic surgeons, sports medicine surgeons, orthopedic trauma surgeons, and deformity surgeons most valued promotion and reward as their primary goal. The most limiting barrier for academic consultants was the need for more research assistants. In contrast, more research time was needed among the non-academic consultants, registrars, fellows, and residents. The most important goal for academic consultants’ research participation was personal interest in research activities. The primary goal of non-academic consultants was promotion and reward, whereas residents and fellows focused on enhancing their personal CVs. On the other hand, the lack of research assistants was the main barrier among almost all orthopedic subspecialties. In contrast, personal interest, promotion, and reward were the most influential goals behind research participation across most orthopedic subspecialties.

Our findings have implications for national academic policy. Institutions should prioritize structured mentorship programs, provide protected research time, and recognize research output in performance evaluations, aligning with Saudi Vision 2030’s goals of promoting research excellence and innovation.

Given the challenges faced by orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia in terms of research productivity, it is crucial for institutions to prioritize dedicated research time and provide robust support systems. Strengthening research training and mentorship, alongside increasing financial and institutional backing, can significantly improve research engagement. Simplifying administrative processes and fostering collaborative efforts will also play a vital role in encouraging participation. Moreover, recognizing and rewarding research achievements will help nurture a research-driven culture, ultimately enhancing evidence-based practices within the field. Furthermore, countries risk losing their most talented researchers due to inadequate research infrastructure and support, leading to brain drain, where skilled professionals seek better opportunities abroad[14]. Addressing these challenges is vital to retain local talent and advance the overall research landscape.

Because this was a cross-sectional study, causal relationships cannot be inferred. Future longitudinal research should explore how institutional reforms influence sustained research engagement and productivity over time.

Orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia face multifaceted challenges that limit research productivity, including insufficient time, training, and support staff. Addressing these barriers through institutional reforms, such as protected research time, mentorship, and funding, could substantially enhance engagement. The findings offer practical insights for academic leaders and policymakers seeking to strengthen the national orthopedic research ecosystem. Future longitudinal studies should explore the long-term impact of such institutional initiatives.

| 1. | Latif R. Medical and biomedical research productivity from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (2008-2012). J Family Community Med. 2015;22:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Alghanim SA, Alhamali RM. Research productivity among faculty members at medical and health schools in Saudi Arabia. Prevalence, obstacles, and associated factors. Saudi Med J. 2011;32:1297-1303. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Guraya SY, Khoshhal KI, Yusoff MSB, Khan MA. Why research productivity of medical faculty declines after attaining professor rank? A multi-center study from Saudi Arabia, Malaysia and Pakistan. Med Teach. 2018;40:S83-S89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Guraya SY, Norman RI, Khoshhal KI, Guraya SS, Forgione A. Publish or Perish mantra in the medical field: A systematic review of the reasons, consequences and remedies. Pak J Med Sci. 2016;32:1562-1567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Raftery J, Kerr C, Hawker S, Powell J. Paying clinicians to join clinical trials: a review of guidelines and interview study of trialists. Trials. 2009;10:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nagel CL, Kirby MA, Zambrano LD, Rosa G, Barstow CK, Thomas EA, Clasen TF. Study design of a cluster-randomized controlled trial to evaluate a large-scale distribution of cook stoves and water filters in Western Province, Rwanda. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2016;4:124-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mitwalli HA, Al Ghamdi KM, Moussa NA. Perceptions, attitudes, and practices towards research among resident physicians in training in Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20:99-104. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Forster C, Vanhaudenhuyse A, Gast P, Louis E, Hick G, Brichant JF, Joris J. Intravenous infusion of lidocaine significantly reduces propofol dose for colonoscopy: a randomised placebo-controlled study. Br J Anaesth. 2018;121:1059-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Alrashidi Y, Alrabai H. Barriers to conduction or completion of research projects among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2021;5:103-108. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Falavigna A, Khoshhal K. Research education: Is it an option or necessity? J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2019;3:239-240. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Alomar AZ, Altwaijri N, Khoshhal KI. Orthopedic research productivity of KSA: First bibliometric analysis. J Taibah Univ Med Sci. 2024;19:995-1010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | El-Sobky TA. Insufficient orthopedic research productivity of the arab countries: Who is to blame? J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2020;4:1-2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Khalifa AA, Ahmed AM. Scarcity of publications from arab countries in one of the q1 orthopedic journals, is it us or the journal? J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2020;4:9-13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Raghuwanshi A, Srivastav AK. Identifying and analyzing variables in musculoskeletal healthcare research. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2024;9:49-57. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Hess D. Commentary about article “Barriers to conduction or completion of research projects among orthopedic surgeons in Saudi Arabia”. J Musculoskelet Surg Res. 2021;5:221-222. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/