Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.112006

Revised: September 27, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 178 Days and 7.3 Hours

Humeral shaft fractures are common and vary by age, with high-energy trauma observed in younger adults and low-impact injuries in older adults. Radial nerve palsy is a frequent complication. Treatment ranges from nonoperative methods to surgical interventions such as intramedullary K-wires, which promote faster reha

To evaluate the outcomes of managing humeral shaft fractures using closed reduction and internal fixation with flexible intramedullary K-wires.

This was a retrospective cohort study analyzing the medical records of patients with humeral shaft fractures managed with flexible intramedullary K-wires at King Abdulaziz Medical City, using non-random sampling and descriptive ana

This study assessed the clinical outcomes of 20 patients treated for humeral shaft fractures with intramedullary K-wires. Patients were predominantly male (n = 16, 80%), had an average age of 39.2 years, and a mean body mass index of 29.5 kg/m2. The fractures most frequently occurred in the middle third of the humerus (n = 14, 70%), with oblique fractures being the most common type (n = 7, 35%). All surgeries used general anesthesia and a posterior approach, with no intraoperative complications reported. Postoperatively, all patients achieved clinical and radiological union (n = 20, 100%), and the majority (n = 13, 65%) reached an elbow range of motion from 0 to 150 degrees.

These results suggest that intramedullary K-wire fixation may be an effective option for treating humeral shaft fractures, with favorable outcomes in range of motion recovery, fracture union, and a low rate of intraoperative complications.

Core Tip: This study aimed to present the clinical outcomes of humeral shaft fractures managed with intramedullary K-wires in a closed reduction approach. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because dealing with humeral shaft fractures is somehow quite common, and the type of management is crucial. Identifying the type of fixation and different options is important in optimizing the outcomes in addition to patients’ satisfaction and regain of function as soon as possible. This study offers good evidence regarding the effectiveness of the technique utilized in the management of humeral shaft fractures, addressing key gaps in the current literature.

- Citation: Abdulsamad MA, AlMugren TS, Saeed AI, Alrogy WA, Alanazi LD, Alsaqer OM, Alanbar FT, Alfarraj AH, Aljaafri ZA. Clinical outcomes of humeral shaft fractures managed with intramedullary K-wires: A closed reduction approach. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 112006

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/112006.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.112006

Humeral shaft fractures account for about 1%-5% of all types of fractures. The annual incidence is estimated to be between 13 and 20 cases per 100000 individuals, with likelihood increasing with age[1]. Humeral shaft fractures have a bimodal age distribution. In younger adults, they are usually as a result of high-energy trauma; in older adults, they are often due to low-impact injuries[2].

Humeral shaft fractures can be classified based on the fracture line (spiral, oblique, transverse, or comminuted), the location (proximal, middle, or distal third), whether the fracture is open or closed, and the condition of the bone (normal or diseased)[3,4]. Risk factors include high-impact trauma from car accidents, sports injuries, work-related incidents, and physical assault. Low-impact fractures, often caused by indirect trauma such as falls on an outstretched arm, are more common in older adults and those with underlying bone conditions[2]. Radial nerve palsy is the most common nerve injury associated with humeral shaft fractures. A total of 4517 fractures were reported in 21 studies out of 25, with 532 cases of radial nerve palsy, amounting to a prevalence of 11.8%[5].

Management of humeral shaft fractures can be nonoperative or operative. One surgical option includes the use of multiple intramedullary Kirschner wires (K-wires)[6,7]. Positive outcomes with intramedullary K-wires suggest that they may offer greater effectiveness than conservative treatments and immobilization techniques as they facilitate quicker recovery and better restoration of elbow movement. Khan et al[8] demonstrated that employing several intramedullary K-wires resulted in favorable clinical and functional outcomes.

Our approach to flexible intramedullary K-wire fixation for humeral shaft fractures was designed to achieve the best possible clinical and functional outcomes with minimal complications. This technique allows patients to commence range-of-motion exercises immediately, potentially reducing the risk of postoperative stiffness and discomfort. Addi

The use of flexible intramedullary K-wires for treating humeral shaft fractures is quite rare in clinical practice, particularly among adults. Additionally, there is limited research on this approach, with only a few studies exploring this operative technique. There is a clear need for high-quality studies assessing the results of intramedullary K-wire fixation. This study aims to evaluate the outcomes of treating humeral shaft fractures using closed reduction and internal fixation (CRIF) with several flexible intramedullary K-wires.

This study was conducted at King Abdulaziz Medical City (KAMC) in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. All patients with humeral shaft fracture managed with intramedullary K-wire fixation were included. All patients were over 14 years old and admitted to the hospital with humeral shaft fractures, closed fractures, adequate neurovascular status, and stable general condition. Exclusion criteria included incomplete or insufficient records for evaluating outcomes, the use of other fixation methods for humeral shaft fracture, open fractures, and confirmed malignancy or recent infection prior to the surgery. This investigation used a retrospective cohort study design, and the sample comprised 20 patients following application of the exclusion criteria. A non-probability consecutive sampling technique was used, including all patients who met the inclusion criteria.

Following induction of general anesthesia and endotracheal intubation, the patient was positioned prone. In selected cases, a lateral decubitus position with the affected side facing upward was used. Fluoroscopic imaging was obtained to confirm adequate visualization of both the fracture site and the entire humerus. The operative field was then prepared and draped in the standard sterile fashion.

A posterior longitudinal skin incision, approximately 3 cm in length and located just proximal to the olecranon fossa, was made. Dissection was carried down to the triceps tendon, which was split longitudinally to expose the humeral cortex. A posterior cortical window measuring about 1 cm × 1 cm was created 1-2 cm proximal to the olecranon fossa using a 4.5 mm drill bit. The window was subsequently enlarged with a bone awl to facilitate wire insertion.

Flexible K-wires (2-3.5 mm) were then contoured with three bends (proximal, middle, and distal) to achieve three-point fixation within the intramedullary canal. The first wire was introduced through the bone window using a T-handle chuck and advanced across the fracture site under fluoroscopic guidance (anteroposterior and lateral views) while maintaining reduction, until it reached the proximal humerus. Additional wires (typically two to three) were inserted in a similar manner to occupy at least 80% of the medullary canal, spreading proximally in a bouquet configuration. As many wires as required were placed to achieve stable fixation.

Once satisfactory alignment and rotation were confirmed, the distal ends of the wires were bent to approximately > 90° with pliers to prevent migration and minimize prominence. The surgical site was then irrigated, and closure performed in layers: The triceps tendon with 0 Vicryl, subcutaneous tissue with 2-0 Vicryl, and the skin with clips. A sterile dressing was applied, and the patient repositioned supine. Figure 1 illustrates the implemented technique for one of the patients.

Postoperatively, a functional brace could be provided for patient comfort; however, this was not required for all cases and does not contribute to fracture stability. Patients were allowed to begin immediate passive range-of-motion exercises for both the elbow and shoulder joints. Most patients were discharged the following day with a follow-up appointment scheduled at 2 weeks for wound inspection and skin clip removal. At 2-3 weeks postoperatively, patients were referred to physiotherapy to initiate active range-of-motion exercises for the shoulder and elbow. Strengthening exercises were introduced once radiographic evidence of fracture healing was observed.

Follow-ups were conducted through regular outpatient visits, including clinical assessment and radiographs at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months postoperatively. Generally, once complete fracture union is achieved, K-wire removal may be considered if requested by the patient, typically around 6-8 months after fixation. Removal is not mandatory for all patients. When performed, it is a brief operative procedure carried out under regional or general anesthesia.

Data were collected using a data collection sheet after the identification of patients who fit the research criteria. Patient information was collected from the electronic health records of the surgery department at KAMC in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The data were first entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, United States), then were analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 29.0 (IBM-SPSS; Armonk, NY, United States).

The data sheet included demographic data: Age, gender, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities, and smoking status, as well as fracture location. In addition to surgical data, details on fracture-related details, presence of an open fracture, surgery duration, time to union, fixation failure, postoperative hardware prominence, intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusions, postoperative range of motion, non-union, postoperative infection, immobilization period, and time to hardware removal were also included.

After the data were entered into the Excel spreadsheet, comprehensive statistical analysis was conducted on the dataset, encompassing both descriptive and inferential methodologies. Descriptive analysis was conducted to summarize the patient demographic characteristics. The χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate the association between categorical variables. Subsequently, an independent samples T test was used to determine the score difference between continuous variables. Patient consent was not required due to the retrospective nature of this study. All data were kept confidential and patient privacy assured. No identifiers were collected. All copies were kept in a secure place within the KAMC premises. Data access was restricted to the study group members.

This study included 20 patients for the assessment of clinical outcomes of humeral shaft fractures managed with intramedullary K-wires (Table 1). Notably, the sample predominantly consisted of male patients (n = 16, 80%), with female patients comprising 20% (n = 4). The average patient age was 39.2 years with a standard deviation of 23.5 years, ranging from 14 years to 83 years. The mean BMI was 29.5 kg/m2, with a standard deviation of 7.5 kg/m2 and a range of 17.2 kg/m2 to 48.2 kg/m2. The majority of patients were nonsmokers (n = 18, 90%), and 45% had other comorbidities (n = 9).

| Variable | Value | |

| Gender | Female | 4 (20.0) |

| Male | 16 (80.0) | |

| Age (years) | mean ± SD | 39.2 ± 23.5 |

| Range | 14-83 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | mean ± SD | 29.5 ± 7.5 |

| Range | 17.2-48.2 | |

| ASA classification | Class 1 | 6 (30.0) |

| Class 2 | 8 (40.0) | |

| Class 3 | 6 (30.0) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 13 (65.0) |

| Yes | 7 (35.0) | |

| Hypertension | No | 15 (75.0) |

| Yes | 5 (25.0) | |

| Dyslipidemia | No | 16 (80.0) |

| Yes | 4 (20.0) | |

| Smoking status | No | 18 (90.0) |

| Yes | 2 (10.0) | |

| Other comorbidities | No | 11 (55.0) |

| Yes | 9 (45.0) | |

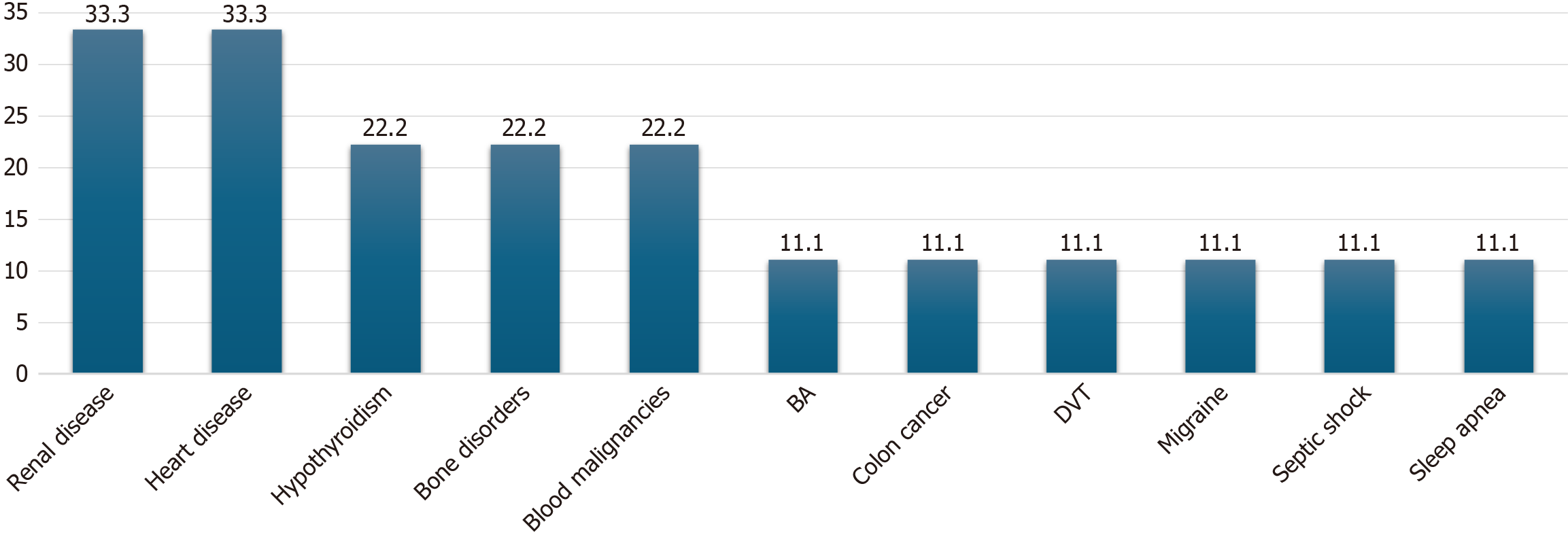

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of comorbidities among the nine patients. Renal and heart diseases were the most common, each reported in three patients (33.3%). Hypothyroidism, bone disorders, and blood malignancies were present in two patients (22.2%). Bronchial asthma, colon cancer, deep vein thrombosis, migraines, septic shock, and sleep apnea were each present in one participant (11.1%).

Table 2 shows the characteristics of the fractures and their management among the 20 patients. The most common mechanisms of injury were falls (n = 8, 40%), followed by motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) (n = 7, 35%) and other forms of trauma (n = 5, 25%). The fractures predominantly occurred in the middle third of the humerus (n = 14, 70%), with fewer in the proximal third (n = 4, 20%) and distal third (n = 2, 10%). Oblique fractures were the most common type (n = 7, 35%), followed by comminuted (n = 5, 25%), with equal occurrences of spiral and transverse fractures (n = 4, 20% each). All patients had intact radial nerves preoperatively. General anesthesia was used in all cases. All surgical approaches were posterior as previously described. The mean duration of surgery was 132.0 minutes. Estimated blood loss was most commonly 100 mL (n = 10, 50%).

| Variable | Value | |

| Mechanism of injury | Fall | 8 (40.0) |

| MVA | 7 (35.0) | |

| Trauma | 5 (25.0) | |

| Fracture location | Proximal third | 4 (20.0) |

| Middle third | 14 (70.0) | |

| Distal third | 2 (10.0) | |

| Fracture type | Oblique | 7 (35.0) |

| Comminuted | 5 (25.0) | |

| Spiral | 4 (20.0) | |

| Transverse | 4 (20.0) | |

| Radial nerve status pre-operative | Intact | 20 (100.0) |

| Type of anesthesia | General | 20 (100.0) |

| Approach | Posterior | 20 (100.0) |

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | mean ± SD | 132.0 ± 67.1 |

| Range | 70-362 | |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 200 | 2 (10.0) |

| 100 | 10 (50.0) | |

| 50 | 8 (40.0) | |

Table 3 shows the effectiveness of CRIF, intraoperative complications, and postoperative outcomes among patients. No intraoperative complications were reported. All patients had a hospital stay of 1 day and maintained intact radial nerve status postoperatively. Wound condition at the first follow-up visit was uniformly positive, with all wounds clean. Both clinical and radiological union were achieved in all cases. The average time until clinical union was 8 weeks, with a SD of ± 5 weeks. The average time until radiological union was 14 weeks, with a SD of ± 6 weeks. The average time until K-wire removal was 11.3 months, with a SD of ± 4.3 months, and a range of 3 months to 20 months. Notably, K-wires had not yet been removed in 45% of cases (n = 9).

| Variable | Value | |

| Intra-op complications | None | 20 (100.0) |

| Length of stay | One day | 20 (100.0) |

| Radial nerve status post-operative | Intact | 20 (100.0) |

| Wound complications at the first follow-up visit | Clean wound | 20 (100.0) |

| Clinical union | Yes | 20 (100.0) |

| Radiological union | Yes | 20 (100.0) |

| Time till clinical union (weeks) | mean ± SD | 8 ± 5 |

| Time till radiological union (weeks) | mean ± SD | 14 ± 6 |

| Time still K-wires removal (months) | mean ± SD | 11.3 ± 4.3 |

| Range | 3-20 | |

| Not yet removed | 9 (45) |

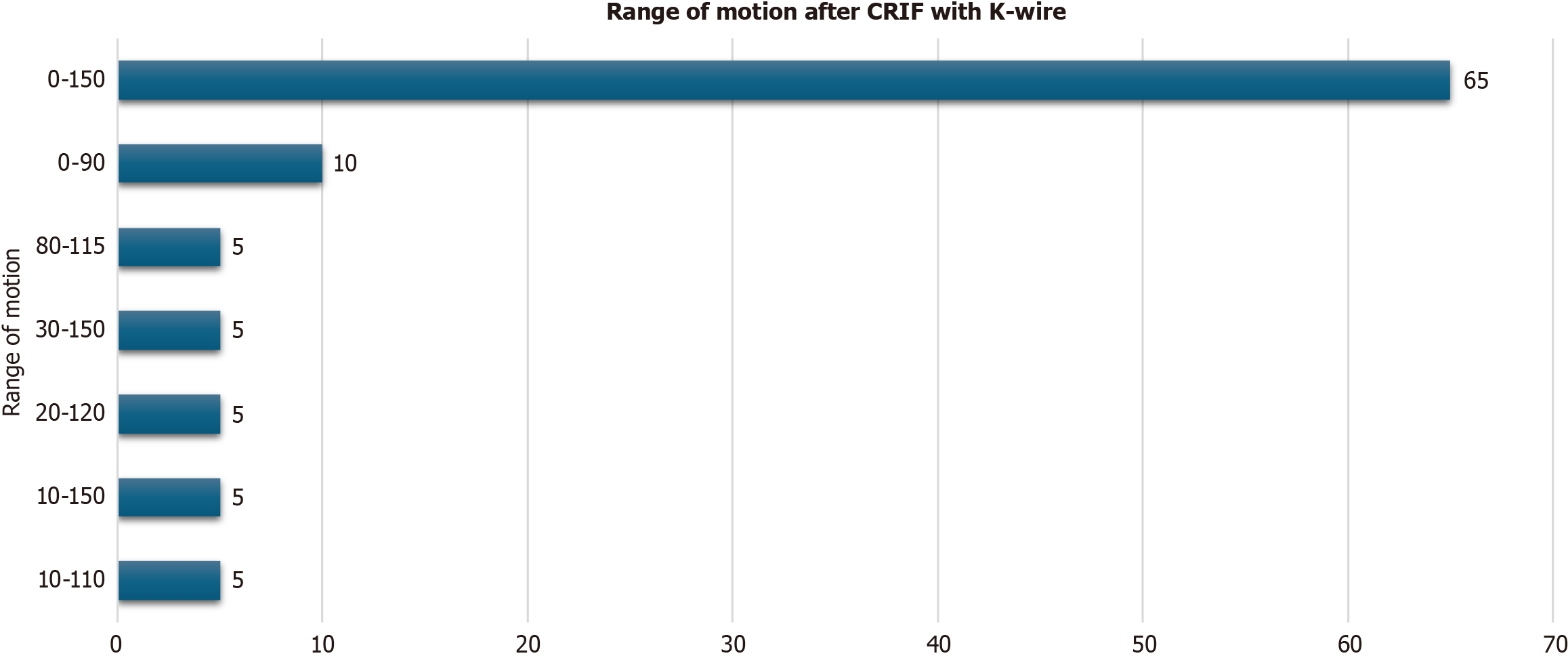

Figure 3 shows the outcomes of range of motion after CRIF with K-wire among the 20 patients. Notably, the majority (n = 13, 65%) achieved a range of motion spanning from 0 degree to 150 degrees, demonstrating significant mobility restoration. However, the remaining patients experienced more restricted ranges of motion.

Table 4 shows the association between various sociodemographic parameters and the range of motion achieved postoperatively among the 20 patients. Notably, the gender distribution showed that a larger portion of males achieved the maximum 0-150-degree range (n = 11, 68.8%) compared with females; however, this was not statistically significant (P = 0.587). Age and BMI showed slight variations in means between the two motion ranges; however, these differences also did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.492, age; P = 0.893, BMI). Comorbidities and smoking status did not significantly influence postoperative motion outcomes.

| Range of motion after intervention | P value | |||

| Other lower ranges | 0-150 degree | |||

| Gender | Female | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | 0.5871 |

| Male | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.8) | ||

| Age (years) | mean ± SD | 34.1 ± 18.7 | 42.0 (26.0) | 0.4922 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | mean ± SD | 29.2 ± 8.5 | 29.7 (7.2) | 0.8932 |

| ASA classification | 1 | 2 (33.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.4471 |

| 2 | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | ||

| 3 | 1 (16.7) | 5 (83.3) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | No | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.8) | 0.3291 |

| Yes | 1 (14.3) | 6 (85.7) | ||

| Hypertension | No | 6 (40.0) | 9 (60.0) | 0.6131 |

| Yes | 1 (20.0) | 4 (80.0) | ||

| Dyslipidemia | No | 6 (37.5) | 10 (62.5) | 1.0001 |

| Yes | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Others commodities | No | 5 (45.5) | 6 (54.5) | 0.3741 |

| Yes | 2 (22.2) | 7 (77.8) | ||

| Smoking status | No | 5 (27.8) | 13 (72.2) | 0.1111 |

| Yes | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

Table 5 shows the relationship between different management parameters and postoperative range of motion among patients. In terms of the mechanism of injury, falls, MVAs, and other traumas showed varied success in achieving the 0-150-degree range of motion, with falls reaching 75% (n = 6), MVAs 57.1% (n = 4), and other traumas 60% (n = 3); none of these results were statistically significant (P = 0.848). Fracture locations such as proximal and distal thirds more frequently achieved the desired maximum motion range [75% (n = 3) and 100% (n = 2), respectively], although without statistical significance (P = 0.793). Despite the variation in fracture types, no significant differences were found, with oblique and transverse types generally achieving better outcomes.

| Range of motion after intervention | P value | |||

| Other lower ranges | 0-150 degree | |||

| Mechanism of injury | Fall | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 0.8481 |

| MVA | 3 (42.9) | 4 (57.1) | ||

| Trauma | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Fracture location | Proximal third | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | 0.7931 |

| Middle third | 6 (42.9) | 8 (57.1) | ||

| Distal third | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | ||

| Fracture type | Oblique | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | 0.9281 |

| Comminuted | 2 (40.0) | 3 (60.0) | ||

| Spiral | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | ||

| Transverse | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | ||

| Surgery duration (minutes) | mean ± SD | 109.9 ± 21.4 | 144.0 ± 80.4 | 0.2902 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 200 | 2 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.1471 |

| 100 | 2 (20.0) | 8 (80.0) | ||

| 50 | 3 (37.5) | 5 (62.5) | ||

Humeral shaft fractures, accounting for a small percentage of all fractures (1%-5%), occur most frequently from high-energy traumas in younger adults and low-impact incidents such as falls in older adults[9]. These fractures vary by type, location, and whether they are open or closed. Radial nerve palsy is a common complication, occurring in 19% of cases[10]. While nonoperative treatments exist, surgical management using multiple intramedullary K-wires is a valid option, often resulting in faster rehabilitation and improved range of motion with few complications, particularly at the elbow, compared with conservative approaches[7]. This study investigated the clinical outcomes of humeral shaft fractures treated with flexible intramedullary K-wires using a closed reduction approach in a cohort of 20 patients.

Notably, the cohort predominantly consisted of male patients (80%), aligning with the literature which suggests that males are more susceptible to traumatic injuries due to lifestyle and occupational exposures. A study by Ji et al[11] in China reported that the incidence of traumatic humeral shaft fractures is 7.22 per 100000, higher in males (9.63%) than females (4.75%). The mean patient age of 39.2 years also corresponds with previous work reporting that patients with traumatic humeral shaft fractures had a mean age of 42.9 years[11]. Age and BMI did not significantly influence the range of motion postoperatively, contradicting some studies suggesting that older age and higher BMI are associated with poorer outcomes in orthopedic interventions due to diminished bone quality and comorbid conditions which may complicate recovery. Gjorgjievski and Ristevski[12] in 2020 reported a high rate of postoperative complications in surgical management of older adults, and thus, special considerations following orthopedic surgery are necessary. Kinder et al[13] in 2020 demonstrated that patients with abnormal BMIs face an increased risk of complications and poorer outcomes following orthopedic interventions.

Moreover, the current study identified a high prevalence of systemic diseases such as diabetes mellitus (35%), hypertension (25%), and dyslipidemia (20%). The presence of these comorbidities did not significantly affect the range of motion achieved, which is a possible indicator that intramedullary K-wire fixation can be effectively used across a varied patient profile. In this study, the fractures predominantly occurred in the middle third of the humerus, consistent with global fracture distribution patterns[14,15]. The choice of general anesthesia in most cases (90%) and a posterior surgical approach for all patients aligned with standard practices in managing humeral shaft fractures. However, the duration of surgery and estimated blood loss, which varied widely among the patients, were not significantly correlated with postoperative range of motion.

Such fractures were managed by similar techniques and were studied previously with good outcomes. Techniques included flexible intramedullary nailing via Ender or Hackethal nailing[16,17]. However, the use of multiple flexible K-wires is not well documented in the literature for the management of such fractures in adolescents. Regarding the entry point, this study used a posterior approach just proximal to the olecranon fossa, consistent with previous studies[6,18]. This does not violate the olecranon fossa distally, and has an advantage over the antegrade approach as it does not violate the rotator cuff.

The overall effectiveness of the intervention was demonstrated by the 100% rate of both clinical and radiological union and the absence of intraoperative complications. These findings are consistent with studies reporting high success rates for CRIF techniques in treating humeral fractures. Lalrinchhana et al[18] in 2020 showed that CRIF techniques have satisfactory outcomes, with reported union rates of 94.4%. Similarly, a previous case series published by the primary author of 9 cases reported a 100% union rate[7]. There was no reported radial nerve palsy postoperatively in this study, which is consistent with previous work emphasizing the effectiveness and safety of the technique[6,7,17].

Significantly, 65% of patients in this study achieved a range of motion spanning from 0 degree to 150 degrees, indicating a substantial restoration of function. This success rate is comparable to (or better than) outcomes reported in other studies, where the range of motion was notably restricted by factors such as improper pin placement or premature mobilization. However, Attum and Thompson[19] showed that distal humerus fractures have less favorable outcomes than proximal humerus and shaft fractures. About 75% of patients regain elbow motion and strength, with a goal range of motion of 30-130 degrees[18,19]. The absence of a significant impact from sociodemographic variables or comorbid conditions on the range of motion is a positive outcome, suggesting that CRIF with K-wires is an effective method irrespective of patient-specific variables.

As it is known, both conservative and surgical outcomes are acceptable; the goal of this work is to address the complications associated with each intervention and how they differ from the CRIF technique described earlier. In the case of conservative management, there is a risk of nonunion, which could prolong the recovery period[17,20,21]. Open reduction and internal fixation, while associated with higher union rates, carry risks, including iatrogenic radial nerve injury[22,23].

Despite these promising findings, this study has several limitations, including its small sample size and the absence of a comparison group, which may affect the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of the study introduces potential biases in data collection and analysis. Treatment variability and the single-center nature of the study further constrain applicability of the findings across different settings.

This study underscores the efficacy of multiple flexible intramedullary K-wire fixation in treating humeral shaft fractures, highlighting the technique’s potential for high rates of bone union and functional recovery with minimal complications. Key implications for clinical practice include enhancing surgical training, refining patient selection, and focusing on comprehensive postoperative care. Future research should expand on these findings using multicenter trials, longer follow-up periods, controlled trials for comparative effectiveness, and economic evaluations. These would improve the generalizability of the results, enable personalized treatment approaches, and assess the cost-effectiveness of K-wire fixation, contributing to better patient outcomes in orthopedic surgery.

This study indicates that CRIF with K-wires can be a useful approach for managing humeral shaft fractures, with favorable rates of bone union and functional recovery in a varied patient population. These findings add to the existing evidence on orthopedic trauma management; however, further research is needed to clarify outcomes in patients with significant comorbidities.

| 1. | Schoch BS, Padegimas EM, Maltenfort M, Krieg J, Namdari S. Humeral shaft fractures: national trends in management. J Orthop Traumatol. 2017;18:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bounds EJ, Frane N, Jajou L, Weishuhn LJ, Kok SJ. Humeral Shaft Fractures. 2023 Dec 13. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Benegas E, Ferreira Neto AA, Neto RB, Santis Prada Fd, Malavolta EA, Marchitto GO. Humeral Shaft Fractures. Rev Bras Ortop. 2010;45:12-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Updegrove GF, Mourad W, Abboud JA. Humeral shaft fractures. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:e87-e97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shao YC, Harwood P, Grotz MR, Limb D, Giannoudis PV. Radial nerve palsy associated with fractures of the shaft of the humerus: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1647-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Qidwai SA. Treatment of humeral shaft fractures by closed fixation using multiple intramedullary Kirschner wires. J Trauma. 2000;49:81-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abdulsamad AM, Al Mugren T, Alzahrani MT, Alanbar FT, Althunayan TA, Mahayni A, Alfarag AH, Alotaibi MT, Almuqbil M, Alfarraj AH. Outcomes of the Treatment of Humeral Shaft Fractures by Closed Reduction and Internal Fixation With Multiple Intramedullary Kirschner Wires (K-wires). Cureus. 2023;15:e51009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khan AQ, Iraqi AA, Sherwani MK, Abbas M, Sharma A. Percutaneous multiple K-wire fixation for humeral shaft fractures. Saudi Med J. 2007;28:144-146. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gallusser N, Barimani B, Vauclair F. Humeral shaft fractures. EFORT Open Rev. 2021;6:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schwab TR, Stillhard PF, Schibli S, Furrer M, Sommer C. Radial nerve palsy in humeral shaft fractures with internal fixation: analysis of management and outcome. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2018;44:235-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ji C, Li J, Zhu Y, Liu S, Fu L, Chen W, Zhang Y. Assessment of incidence and various demographic risk factors of traumatic humeral shaft fractures in China. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gjorgjievski M, Ristevski B. Postoperative management considerations of the elderly patient undergoing orthopaedic surgery. Injury. 2020;51 Suppl 2:S23-S27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kinder F, Giannoudis PV, Boddice T, Howard A. The Effect of an Abnormal BMI on Orthopaedic Trauma Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Daoub A, Ferreira PMO, Cheruvu S, Walker M, Gibson W, Orfanos G, Singh R. Humeral Shaft Fractures: A Literature Review on Current Treatment Methods. Open Orthop J. 2022;16:e187432502112091. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Oliver WM, Searle HKC, Ng ZH, Wickramasinghe NRL, Molyneux SG, White TO, Clement ND, Duckworth AD. Fractures of the proximal- and middle-thirds of the humeral shaft should be considered as fragility fractures. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:1475-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gomez RW, McHugh RC, Shukla D, Greenhill DA. Flexible Intramedullary Nail Placement in Pediatric Humerus Fractures. JBJS Essent Surg Tech. 2024;14:e23.00071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tarng YW, Lin KC, Chen CF, Yang MY, Chien Y. The elastic stable intramedullary nails as an alternative treatment for adult humeral shaft fractures. J Chin Med Assoc. 2021;84:644-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lalrinchhana H, Badole CM, Mote GB. Humeral shaft fractures treated by closed retrograde intramedullary kirschner wire fixation. Arch Trauma Res. 2020;9:30-34. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Attum B, Thompson JH. Humerus Fractures Overview. 2023 Jul 4. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ali E, Griffiths D, Obi N, Tytherleigh-Strong G, Van Rensburg L. Nonoperative treatment of humeral shaft fractures revisited. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:210-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rämö L, Sumrein BO, Lepola V, Lähdeoja T, Ranstam J, Paavola M, Järvinen T, Taimela S; FISH Investigators. Effect of Surgery vs Functional Bracing on Functional Outcome Among Patients With Closed Displaced Humeral Shaft Fractures: The FISH Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;323:1792-1801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhao JG, Wang J, Wang C, Kan SL. Intramedullary nail versus plate fixation for humeral shaft fractures: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, McKee MD, Schemitsch EH. Compression plating versus intramedullary nailing of humeral shaft fractures--a meta-analysis. Acta Orthop. 2006;77:279-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/