Published online Jan 18, 2026. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.111927

Revised: August 17, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 18, 2026

Processing time: 180 Days and 16.8 Hours

The therapeutic role of neurodynamic mobilization in improving lower limb function in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis remains poorly understood.

To further elucidate the role of neurodynamic mobilization in facilitating knee joint functional recovery.

Thirty-two patients with post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis treated at Chonghua Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Guilin) from March 2024 to August 2025 were randomly assigned to a control group (n = 16) or an intervention group (n = 16). Both groups received eight weeks of conventional treatment; and the intervention group additionally underwent neurodynamic mobilization. Out

There were no significant differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics, including gender, age, body mass index, or surgical side (P > 0.05). Two-way repeated-measures analysis of variance demonstrated significant time × group interaction effects for the visual analogue scale score (F = 13.364, P < 0.05), Lysholm knee score (F = 20.385, P < 0.05), stork stand test (F = 103.756, P < 0.05), and Y-balance test score (F = 8.089, P < 0.05).

Neurodynamic mobilization effectively reduces pain, improves knee function, and enhances lower limb balance in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis.

Core Tip: This study presents an innovative integration of neurodynamic mobilization into conventional rehabilitation protocols for post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis, examining its effects on lower limb function in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. An eight-week randomized controlled trial demonstrated that neurodynamic mobilization effectively alleviates pain, improves knee function, and enhances lower limb balance in these patients. These findings highlight the unique value of this technique in sensory-motor function restoration for early-stage traumatic knee osteoarthritis.

- Citation: Hu JR, He MX, Wei SS, Ren HW, Liu CH, Liu XL, Chen ZC. Effect of neurodynamic mobilization on lower limb function in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis. World J Orthop 2026; 17(1): 111927

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v17/i1/111927.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v17.i1.111927

Post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease of the articular cartilage resulting from knee injury, characterized by cartilage degradation, synovial inflammation, and osteophyte formation. Compared with primary osteoarthritis, it progresses more rapidly and manifests with more complex clinical symptoms, including persistent joint pain, morning stiffness, restricted mobility, and lower limb dysfunction, all of which markedly impair patients’ quality of life[1]. Epidemiological studies indicate an increasing incidence of post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis among middle-aged and elderly populations, with a notable rise in younger patients in recent years, likely attributable to the growing pre

In recent years, neurodynamic mobilization, a rehabilitation technique grounded in the principles of neurodynamics, has shown considerable potential in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain and sports injuries. This technique enhances the sliding capacity of peripheral nerves, reduces neural tissue tension, and modulates neuromuscular control, thereby alleviating pain and restoring joint function. Several preliminary studies have demonstrated its potential efficacy in treating knee joint disorders[5].

Some preliminary studies indicate that combining neurodynamic mobilization with physical therapy may effectively alleviate pain, improve joint range of motion, reduce functional impairment, and enhance limb function. However, neurodynamic mobilization does not appear to outperform other treatment modalities in terms of pain relief, joint mobility, or overall joint function improvement[6]. Other studies have reported that neurodynamic mobilization, when combined with standard physical therapy, enhances the efficacy of physical therapy as an adjunct intervention. With respect to reducing disability, neurodynamic mobilization has been shown to be more effective than exercise therapy alone[7]. Some studies indicate that the therapeutic effects of neurodynamic mobilization are comparable to those of conventional rehabilitation techniques[8].

The effects of neurodynamic mobilization on the musculoskeletal system remain controversial, and existing studies generally present limitations, including small sample sizes and short follow-up periods, which complicate the assessment of long-term efficacy. Furthermore, research specifically targeting patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis is lacking, as most evidence pertains to primary osteoarthritis or postoperative rehabilitation. Critically, the impact of neurodynamic mobilization on overall lower limb function in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis has not been systematically evaluated. Therefore, this study was designed as a randomized controlled trial to investigate the efficacy of neurodynamic mobilization in improving lower limb function in this population, using objective measures such as pain intensity, joint range of motion, gait parameters, and dynamic balance, in comparison with conventional rehabilitation protocols. The findings are intended to provide a novel, non-pharmacological intervention strategy for the rehabilitation of this condition and to further elucidate the role of neurodynamic mobilization in facilitating knee joint functional recovery.

This study employed a double-blind, randomized controlled trial design, with participants in each group blinded to the rehabilitation protocols of the other groups. Prior to participation, all subjects underwent medical screening to exclude specific health conditions. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board of Guilin Vocational College of Life and Health (approval No. GCPEH2024007), in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Potential confounding factors or effect modifiers during the rehabilitation process included the influence of home and work environments, patients’ rehabilitation awareness, and prior rehabilitation experiences.

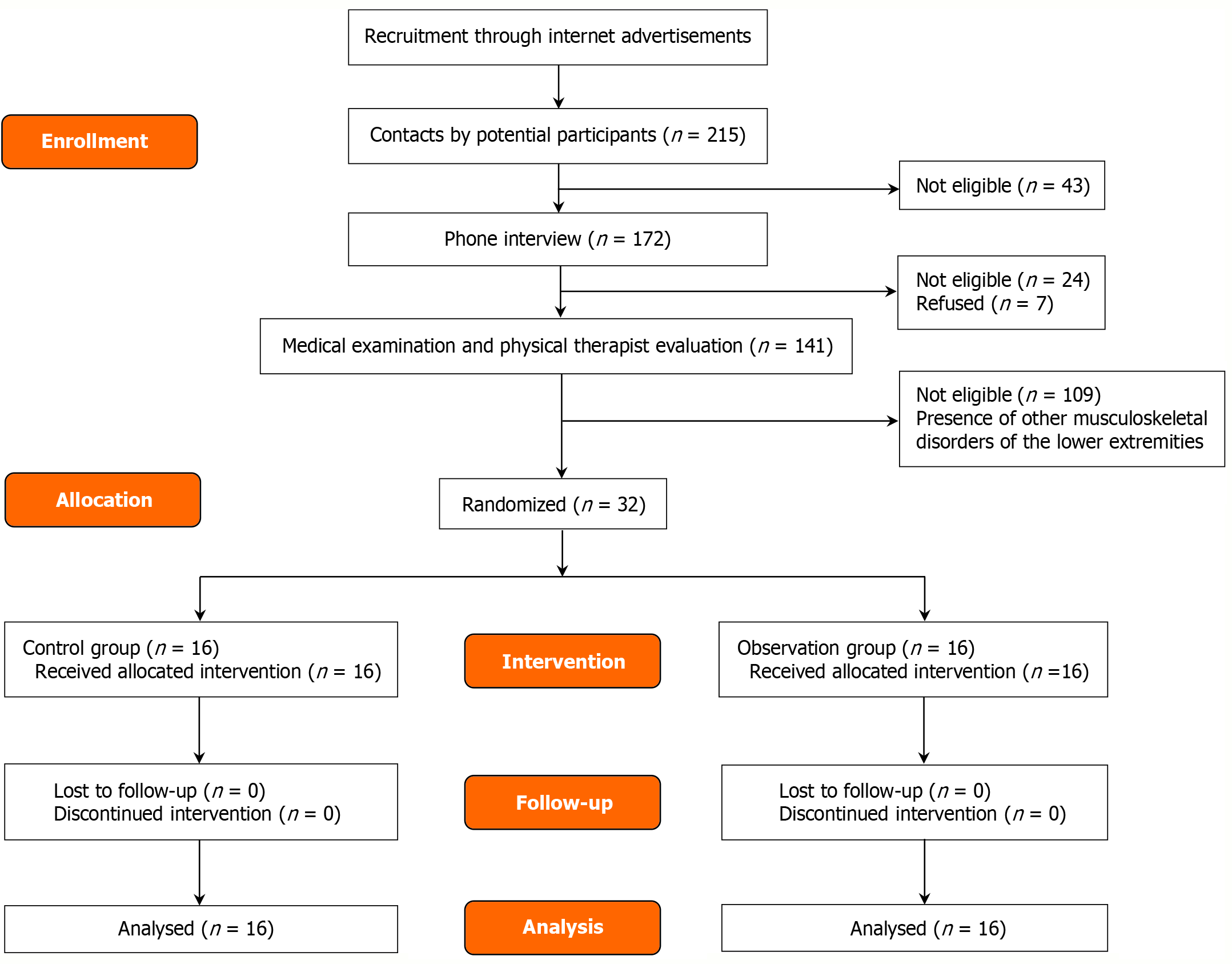

Between March and June 2024, a total of 215 volunteers were recruited in Guilin city through online advertisements. Following preliminary screening of basic eligibility information, 43 individuals were excluded due to age restrictions or incomplete personal data. The remaining 172 candidates underwent telephone interviews, during which the study procedures were explained. Based on self-reported medical conditions, 24 individuals who did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and an additional 7 declined participation due to lack of interest. Ultimately, 141 candidates were invited to Chonghua Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital for medical examinations and rehabilitation assessments conducted by experienced physical therapists. After excluding 109 individuals diagnosed with other musculoskeletal conditions, 32 eligible participants were enrolled. A computer-generated random number table was used to stratify male and female participants, and group allocation was performed by independent personnel not involved in the study, ensuring allocation concealment. The trial employed a double-blind design, with all information regarding study procedures kept strictly confidential. The 32 participants were randomly assigned to a control group (n = 16) and an intervention group (n = 16), with each group including four female participants. All participants completed the full 8-week intervention period, and thus all 32 were included in the final data analysis. The mean age was 30.66 ± 9.19 years. The study flowchart is presented in Figure 1. The study was conducted at Chonghua Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital in Guilin, China, and approved by the ethics committee (Approval No. GCPEH2024007). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Inclusion criteria[9]: (1) Radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis; (2) History of trauma to the affected knee; (3) Kellgren-Lawrence grade I–II; and (4) Age ≥ 18 years. Exclusion criteria: (1) Congenital deformities or tumors of the knee joint; (2) Autoimmune systemic diseases; (3) Severe cardiovascular or cerebrovascular diseases; (4) Severe infectious diseases or osteoporosis; (5) Impaired consciousness, psychiatric disorders, or intellectual disability; (6) Coexisting inflammatory arthritis; (7) Pregnant or postpartum women; (8) Localized bleeding; (9) Active pulmonary tuberculosis; and (10) Sensory neuropathy. Withdrawal criteria: (1) Incomplete baseline data that precludes safety and efficacy analysis; (2) Poor adherence to assessment or treatment; and (3) Premature withdrawal from treatment or failure to complete the evaluation for any reason. Baseline characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1.

| Group | Number | Gender | Age (years) | Height (cm) | Weight (kg) | Body mass index (kg/m2) |

| Control group | 16 | M = 14 | 30.31 ± 9.02 | 170.94 ± 6.61 | 69.19 ± 7.56 | 23.63 ± 1.61 |

| F = 2 | ||||||

| Observation group | 16 | M = 14 | 29.63 ± 9.25 | 171.75 ± 5.03 | 71.25 ± 8.89 | 24.09 ± 2.18 |

| F = 2 | ||||||

| t value | 0.213 | -0.391 | -0.707 | -0.672 | ||

| P value | 0.833 | 0.698 | 0.485 | 0.507 |

Both groups received conventional treatment, with the intervention group additionally undergoing neurodynamic mobilization therapy for a total duration of 8 weeks. Physical therapy involved pulsed ultrasound, with participants seated and the affected knee exposed. A low-intensity pulsed ultrasound device (Exegon 3000+, Smith and Nephew, France) was applied at a frequency of 1 kHz, pulse width of 20 milliseconds, and average intensity of 30 mW/cm2, for 20 minutes per session, once daily, 5 days per week, over 8 weeks. For pharmacological treatment, both groups received oral diclofenac sodium 75 mg (Novartis Pharma Beijing Co., Ltd., approval number H11021640) once daily for 8 weeks. Exercise therapy was performed in accordance with clinical guidelines[10], The exercise program adhered to the principles of individualization, low-impact, and gradual progression, aiming to enhance muscle strength, improve joint mobility, and relieve pain. The protocol included 5-10 minutes of warm-up, followed by quadriceps isometric con

The intervention group received neurodynamic mobilization, adhering to a principle of pain-free and progressive application. The intervention was administered three times per week (with ≥ 48 hours between sessions), with each session lasting 30 minutes, and was conducted in three sequential phases[11]. Phase I (Weeks 1-2) involved basic neurodynamic mobilization techniques targeting the tibial and peroneal nerves. For tibial nerve mobilization, the patient lay supine with the knee flexed, followed by ankle dorsiflexion combined with eversion and toe extension, then progressive knee extension with a straight-leg raise. Each set comprised 10 repetitions, with three sets in total and a 30-second rest between sets. For peroneal nerve mobilization, the patient sat upright with the ankle held in plantarflexion and inversion, followed by knee extension combined with cervical flexion. Each set comprised 8 repetitions, with three sets in total and a 30-second rest between sets. Phase II (Weeks 3-5) introduced neural tension regulation techniques, including sciatic nerve sliding and dynamic neural chain stretching. In the supine position, the patient flexed the knee with ankle dorsiflexion, followed by knee extension. Each set comprised 6 repetitions, with three sets total and a 30-second rest between sets. Subsequently, in the standing position, the patient performed hip extension with adduction, followed by ankle plantarflexion with inversion, and then spinal flexion. Each set comprised 5 repetitions, with four sets total and a 30-second rest between sets. Phase III (Weeks 6-8) focused on functional integration and neuro-biomechanical loading. In the supine position, the patient held an elastic band for resistance, performing hip flexion with ankle dorsiflexion and eversion, followed by knee extension while sliding the sole of the foot along the wall. Each set comprised 8 repetitions, with three sets total and a 30-second rest between sets. The patient then remained supine, performing knee flexion with ankle plantarflexion and inversion, followed by knee extension while sliding the sole of the foot along the wall. Each set comprised 8 repetitions, with three sets total and a 30-second rest between sets.

Visual analogue scale: The visual analogue scale (VAS) score was used to assess the severity of knee joint pain before and after the intervention. A score of 0 indicates no pain, whereas a score of 10 represents maximally severe, unbearable pain. Higher scores indicate more intense pain[12].

Active mobility of knee joint: Prior to testing, patients were positioned in either the supine or prone position, with the hip maintained in a neutral alignment to prevent compensatory movements. Knee range of motion was measured using a goniometer, with the axis aligned to the lateral epicondyle of the femur, the stationary arm parallel to the femur’s longitudinal axis, and the movable arm parallel to the fibula’s longitudinal axis. For active flexion, patients were instructed to slowly flex the knee to the maximal angle while being monitored for any hip compensation or pain. For active extension, patients were instructed to fully extend the knee. Each measurement was repeated three times, and the mean value was recorded[13].

Lysholm score of knee joint: The Lysholm score is a validated scale used to assess knee joint function. It comprises eight clinical domains: Pain (25 points), joint instability (25 points), locking (15 points), swelling (10 points), stair climbing (10 points), squatting (5 points), limp (5 points), and use of support devices (5 points). The total score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating superior knee function[14].

Stork stand test: The stork stand test is a widely used clinical assessment for static balance. Testing should be conducted in a quiet environment with moderate lighting on a level, firm surface. Participants perform the test barefoot. Prior to testing, the examiner explains the procedure in detail and demonstrates the standard protocol. During the formal assessment, participants stand upright, with arms either naturally at their sides or placed on the hips, and eyes facing forward. The affected leg serves as the support leg, while the non-support leg is flexed at the hip and knee to approximately 45°, with the calf hanging naturally without contacting the support leg. The examiner uses a stopwatch to record the duration. An initial 2-3 trial practice with eyes open is conducted to familiarize the participant with the procedure. Once the participant can maintain a single-leg stance for 10 seconds with eyes open, the formal test begins upon the “start” command, at which point the participant closes their eyes and the timer is started simultaneously. The examiner observes the participant closely, and timing is stopped immediately if any termination criteria are met: Significant movement or lifting of the support foot, contact of the lifted foot with the ground or support leg, body tilt exceeding 30°, hands leaving the predetermined position to seek support, participant reporting loss of balance, or reaching the maximum test duration (60 seconds). The test is repeated three times with a 1-2 minute rest between trials, and the best result is recorded as the final outcome[15].

Single hop test: The single hop test quantifies lower limb explosive power, dynamic balance, and neuromuscular control. A difference in jump distance between limbs exceeding 10%-15%, or knee wobbling or pain upon landing, may indicate muscle strength imbalance, joint instability, or incomplete rehabilitation. Participants stand on one leg, with the contralateral leg flexed and suspended, while the maximum single-leg hop distance is recorded. Participants wear athletic shoes and perform a 5-10 minutes warm-up before testing. Each jump must be followed by a stable stance of at least 2 seconds to be considered valid. The test is repeated three times, and the best performance is recorded, with any abnormal landing posture noted[16].

Y-balance test score: Lower limb length was measured as the distance from the medial malleolus to the anterior superior iliac spine on the affected side. Participants stood on one leg at the center of the platform, with both hands placed on the hips. The big toe of the support foot was aligned with the anterior-lateral centerline of the force platform. While maintaining a single-leg stance, participants reached the contralateral leg as far as possible in three directions to push the platform. Force platform readings were recorded with an accuracy of 5 cm, and each direction was tested three times to obtain the maximal value. The final Y-balance test (YBT) score was calculated unilaterally, using the average of the three reach distances normalized to lower limb length, as follows: If the scores for the three directions and lower limb length are a, b, c, and d, the final score = [(a + b + c)/3d] × 100%. A final score of < 95% indicates an increased risk of sports injury on that side[17].

Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 26.0. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD. A two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine differences across outcomes, with group (control vs intervention) as the between-subjects factor and time (pre-test vs post-test) as the within-subjects factor. Baseline differences between groups were assessed using independent-samples t-tests. A significance level of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted by an independent statistician.

As shown in Table 2, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group before the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (F = 170.455, P < 0.05) and a significant interaction between time and group (F = 13.364, P < 0.05). Simple effects analysis indicated a significant difference in VAS scores between the two groups after the intervention (F = 5.000, P < 0.05). Within-group comparisons showed that VAS scores significantly differed before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 44.182, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 139.636, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 3, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group prior to the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time (F = 413.257, P < 0.05), while the interaction effect between time and group was not significant (F = 0.128, P > 0.05). Within-group comparisons revealed significant differences in active mobility of knee joint before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 395.724, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 432.837, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 4, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group before the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (F = 498.726, P < 0.05) and a significant interaction effect between time and group (F = 20.385, P < 0.05). Within-group comparisons demonstrated significant differences in Lysholm scores before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 315.892, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 203.419, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 5, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group prior to the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (F = 22.143, P < 0.05) and a significant interaction effect between time and group (F = 103.756, P < 0.05). Within-group comparisons indicated significant differences in stork stand test performance before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 352.147, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 972.834, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 6, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group before the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of time (F = 158.921, P < 0.05), while the interaction effect between time and group was not significant (F = 0.521, P > 0.05). Within-group comparisons showed significant differences in single hop test distances before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 25.307, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 145.571, P < 0.05).

As shown in Table 7, there was no significant baseline difference between the control group and the observation group prior to the intervention. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time (F = 201.892, P < 0.05) and a significant interaction effect between time and group (F = 8.089, P < 0.05). Within-group comparisons showed significant differences in YBT scores before and after the intervention in both the control group (F = 63.871, P < 0.05) and the observation group (F = 138.024, P < 0.05).

This section systematically analyzes the factors underlying changes in the outcome measures for both the control and intervention groups.

No significant differences in VAS scores were observed between the groups at baseline. Following the intervention, the observation group exhibited significantly lower VAS scores compared with the control group, indicating that neurodynamic mobilization effectively reduces knee pain. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, demonstrating that VAS scores decreased over time regardless of group. The main effect of group was not significant, suggesting that group differences alone were not pronounced. Importantly, a significant interaction between time and group indicated that the trajectory of pain reduction in the observation group differed over time from that in the control group, reflecting a more sustained analgesic effect.

The pronounced reduction in VAS scores observed in the observation group in the simple effects analysis may be attributed to neurodynamic mobilization’s effects on peripheral nerve mechanical desensitization, spinal and central pain modulation, and regulation of the neuro-immune-synovial axis. Previous studies indicate that pain in knee osteoarthritis patients is not solely linked to joint degeneration but also involves abnormal sensitization of nerve endings. Neurodynamic mobilization, by dynamically tensioning the nerve sheaths, may enhance nerve tissue sliding and local microcirculation, thereby attenuating nociceptive signal transmission[18]. A recent randomized controlled trial by Rao et al[19], demonstrated that neurodynamic mobilization significantly increased the pain pressure threshold in patients with knee osteoarthritis, suggesting that its effects may involve activation of opioid receptors in the spinal dorsal horn and engagement of descending pain inhibitory pathways. This mechanism aligns with the sustained analgesic effect observed in the present study. Another study reported that colony-stimulating factor 1 concentrations in the synovial fluid of knee osteoarthritis patients were significantly elevated and positively correlated with inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β. Neurodynamic mobilization may enhance local microcirculation, attenuate the release of neurogenic inflammatory mediators, and indirectly suppress synovial inflammation[20].

Neurodynamic mobilization may serve as a key component of a stepped treatment strategy, particularly for patients with neurodynamic abnormalities or those preferring non-invasive interventions. Nevertheless, the molecular mecha

At baseline, no significant differences were observed in the active range of motion of the knee joint between the groups. Following the intervention, both groups exhibited significant improvements in knee range of motion compared with baseline; however, no statistically significant differences were detected between the groups. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, indicating that range of motion improved over time. The interaction between time and group was not significant, suggesting that neurodynamic mobilization did not confer additional benefits in enhancing joint range of motion.

From a joint kinematics perspective, restricted knee movement in osteoarthritis patients is typically attributable to multiple factors, including cartilage wear-induced joint surface irregularities, synovitis-related swelling and pain, joint capsule contracture, and muscle spasms. Neurodynamic mobilization, primarily targeting neural tissue plasticity and nerve sliding, may alleviate pain by enhancing the neurodynamic state, but it does not directly address the mechanical constraints of the joint[21]. The relationship between accessory and physiological movements of the knee joint offers a valuable framework for interpreting the findings of this study. According to joint mobilization theory, accessory movements typically must be restored before physiological movements can be fully recovered. In the present study, conventional treatment may have sufficiently addressed joint accessory movement limitations, whereas neurodynamic mobilization, as an adjunctive intervention, had limited capacity to further enhance physiological movements[22]. Additionally, the motor control mechanisms of the knee joint warrant consideration. Research has shown that patients with knee osteoarthritis frequently exhibit quadriceps inhibition, a phenomenon characterized by reflexive reductions in muscle activity secondary to joint damage[23]. Although theoretically, neurodynamic mobilization could mitigate this inhibition by enhancing nerve conduction, in the present study, patients with mild traumatic arthritis may have already achieved sufficient restoration of muscle control through conventional treatments, rendering the additional benefit of neurodynamic mobilization less evident. Furthermore, the load-bearing characteristics of the knee joint may influence the efficacy of neurodynamic mobilization. In a pathological environment dominated by mechanical stress, where the knee joint supports the majority of body weight, the contribution of neural factors to functional improvement may be relatively limited. Particularly in patients with existing structural alterations, neurodynamic mobilization is unlikely to reverse established bony deformities and abnormal force lines, which may fundamentally explain the lack of significant improvement in range of motion.

Although this study did not observe significant improvements in knee joint active range of motion following neurodynamic mobilization, the findings nonetheless offer important clinical implications and practical insights. These results may assist clinicians in more judiciously evaluating the role of neurodynamic mobilization within the comprehensive management of knee osteoarthritis, optimizing the selection and implementation of rehabilitation strategies, and providing patients with more precise prognostic guidance.

At baseline, no significant differences were observed in Lysholm scores between the two groups. Following the intervention, the observation group demonstrated significantly higher Lysholm scores than the control group, indicating greater efficacy in improving knee joint function. Repeated measures analysis revealed a significant main effect of time, suggesting that Lysholm scores improved significantly over time regardless of the intervention. The main effect of group was not significant, indicating that, when considering only group factors without temporal changes, differences between the groups were not apparent. Importantly, the interaction between time and group was significant, suggesting that the trajectory of improvement in the observation group differed from that of the control group, with potentially greater long-term sustainability in knee joint function. This effect may be attributed to the adjunctive inclusion of neurodynamic mobilization in the observation group.

Serrano-García[24] and colleagues demonstrated that home-based active neurodynamic training is both feasible and safe for arthritis patients, producing significant improvements in pain reduction and functional outcomes. In their trial, 30 patients aged 50 years and older completed a 6- to 8-week home-based intervention, resulting in substantial decreases in pain intensity and notable improvements in Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores. Additionally, 93.3% of participants reported perceivable benefits from the intervention. Similarly, Weleslassie et al[25] reported that exercise combined with mobilization positively influenced pain relief and functional outcomes in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Participants receiving combined exercise and mobilization demonstrated greater reductions in pain and increases in quadriceps peak torque, resulting in higher lower limb function scores. Furthermore, a systematic review indicated that patients with knee osteoarthritis exhibit diminished motor cortex activation and central nervous system sensitization during movement tasks. Neurodynamic mobilization techniques may alleviate pain and enhance function by improving nerve gliding, increasing local blood flow, and reducing neural tension[26].

Research on neurodynamic mobilization techniques remains limited in both quantity and quality. Additional high-quality randomized controlled trials are required to determine whether these techniques can improve lower limb function. Furthermore, the long-term effects and underlying mechanisms of neurodynamic mobilization remain to be elucidated.

Stork stand test: At baseline, no significant differences were observed between the two groups. Following the intervention, the observation group exhibited significantly longer stork stand test times than the control group, indicating that neurodynamic mobilization may be more effective in enhancing balance function. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, demonstrating that test times increased significantly over time for both groups. The main effect of group was also significant, indicating overall superior performance in the observation group. Importantly, the interaction between time and group was significant, suggesting that the trajectory of improvement in the observation group differed from that of the control group, with balance improvements potentially exhibiting greater sustainability and cumulative effects.

The stork stand test is a balance assessment that heavily depends on proprioceptive input. When visual cues are removed, proprioceptive feedback from lower limb joints and soft tissues becomes a critical factor for maintaining balance. Neurodynamic mobilization may enhance peripheral nerve mobility and proprioceptive input, modulate pain perception and γ-motor neuron excitability, and facilitate the reorganization of neuromuscular control and inter-joint coordination[27]. By enhancing the gliding capacity of neural tissues, neurodynamic mobilization may directly improve proprioceptive conduction efficiency around the knee joint. In patients with knee osteoarthritis, joint degeneration and chronic inflammation can result in microadhesions and heightened mechanical sensitivity in nerve branches traversing the joint. Neurodynamic mobilization, through repeated stretch-relaxation cycles, facilitates neural tissue gliding at peripheral interfaces and reduces adhesions between nerves and surrounding tissues, thereby improving microcirculation within nerve fibers and axoplasmic transport. These mechanical enhancements may increase the conduction efficiency of la sensory fibers (primary endings of muscle spindles) and II fibers (secondary endings of muscle spindles and joint mechanoreceptors), allowing the central nervous system to receive more precise information regarding joint position and subtle postural oscillations[28]. Conversely, pain can disrupt muscle coordination through reflex inhibition mechanisms, and neurodynamic mobilization may indirectly enhance stork stand test performance by modulating pain-processing pathways at the spinal cord level. Research indicates that mechanical neural stimulation can activate inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, thereby reducing the transmission of nociceptive signals to the central nervous system via the “pain gate control” mechanism. This analgesic effect may attenuate excessive γ-motor neuron excitability induced by pain, restoring normal muscle spindle sensitivity. Furthermore, the stork stand test requires coordinated stability across multiple joints - ankle, knee, and hip - whereas patients with knee osteoarthritis often exhibit abnormal movement patterns due to pain and structural joint changes. Neurodynamic mobilization may enhance inter-joint coordination by facilitating the reorganization of neuromuscular control. Improved neural gliding can promote more physiological motor unit recruitment patterns, reducing compensatory muscle contractions. Additionally, neurodynamic mobilization may optimize the timing and intensity of muscle activation in the innervated muscles, thereby improving postural control efficiency.

The significant enhancement in stork stand test performance following neurodynamic mobilization may result from multiple neurophysiological mechanisms: At the peripheral level, by enhancing neural gliding and proprioceptive input; at the spinal cord level, by modulating pain processing and γ-motor neuron activity; and at the motor control level, by optimizing neuromuscular coordination across joints. These mechanisms collectively enable patients to maintain a single-leg stance effectively even in the absence of visual input, indicating a marked improvement in the central nervous system’s postural control capacity.

There was no significant difference in single-hop distance between the two groups prior to the intervention. Post-intervention, although the observation group exhibited a slightly greater single-hop distance than the control group, the difference was not statistically significant. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, indicating that single-hop distance improved significantly over time regardless of the intervention. The main effect of group was not significant, suggesting that when considering only the group factor without accounting for temporal changes, no apparent difference existed between groups. Furthermore, the interaction effect between time and group was not significant, indicating that the temporal trends in intervention effects were comparable between the two groups.

The single hop test, as a complex movement demanding lower-limb explosive power and joint stability, is influenced not only by pain but also by muscle strength, joint mobility, and neuromuscular control. Research has demonstrated that patients with chronic knee pain often exhibit peripheral nerve adaptations, including reduced nerve conduction velocity and altered nerve excitability[29]. Neurodynamic mobilization therapy theoretically enhances neurophysiological function by improving intraneural microcirculation and axoplasmic transport. However, these physiological adaptations may require a longer intervention period to translate into measurable improvements in functional performance, particularly for the single hop test, which demands high coordination and explosive power. The 8-week intervention in this study may have been insufficient for the full potential benefits of neurodynamic mobilization to manifest. Previous research has shown that even basic strength training and joint mobility exercises can elicit short-term improvements in lower-limb explosive performance[30]. When conventional therapy in the control group is already effective, the incremental benefits of additional interventions may be limited. Successful execution of the single hop test requires coordinated lower-limb muscle activation, adequate knee joint stability, and sufficient joint mobility. Among these factors, muscle strength and joint mechanical stability are more directly influenced by strength training and joint stability exercises in conventional therapy rather than by neurodynamic mobilization, whose primary objectives target neural tissue mobility and motor control. Some studies suggest that neurodynamic mobilization may more effectively enhance motor control and temporal coordination than purely increase strength or explosive power[31]. This may explain why, in the present study, although both groups improved in single hop test distance, the experimental group did not demo

The single hop test distance, as a solitary measure, may not capture the full spectrum of benefits conferred by neurodynamic mobilization therapy. Future research should consider including additional assessments, such as dynamic balance and directional agility tests, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation of the effects of neurodynamic mobilization on the functional status of patients with knee osteoarthritis.

There were no significant differences in YBT scores between the two groups at baseline, indicating comparability. Following the intervention, the YBT scores in the experimental group were significantly higher than those in the control group, suggesting that neurodynamic mobilization therapy markedly enhances dynamic balance. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of time, indicating that YBT scores improved significantly over time irrespective of the intervention. The main effect of group was not significant, implying that, when considering only group differences without accounting for temporal changes, no apparent difference was observed. Importantly, the interaction effect between time and group was significant, indicating that the trajectory of improvement in the experimental group differed from that of the control group, with potential for greater sustainability and cumulative benefits in dynamic balance.

The YBT demands precise proprioceptive input, motor coordination, and postural control strategies, all of which rely heavily on the integrity of central nervous system integration and the efficiency of peripheral nerve conduction. The marked improvement in YBT scores observed in the neurodynamic mobilization group in this study may be attributed to the intervention’s ability to enhance the mechanical properties of peripheral nerves, thereby directly modulating proprioceptive afferent input, regulating spinal-level neural excitability to improve motor control, and optimizing central sensorimotor integration. Patients with knee osteoarthritis frequently exhibit functional impairments of joint mechanoreceptors, resulting in diminished postural control. The sliding techniques employed in neurodynamic mobilization can reduce mechanical sensitivity of neural tissues and enhance intraneural microcirculation, thereby improving sensory feedback from muscle spindles and Golgi tendon organs. This mechanism aligns with the findings of Danazumi et al[32], who reported that a 52-week neurodynamic mobilization intervention significantly improved proprioceptive accuracy in patients with chronic low back pain, thereby enhancing dynamic balance performance. Animal studies have demo

Although the YBT demonstrates good reliability and validity, as an active functional assessment, its outcomes may be affected by the participant’s level of effort. Future studies could integrate objective measures, such as quantitative posturography or surface electromyography, to more comprehensively evaluate the effects of neurodynamic mobilization on postural control mechanisms. Current evidence suggests that the therapeutic efficacy of neurodynamic mobilization may be closely associated with intervention frequency, session duration, and the total treatment course. Future research should investigate the impact of different dosing protocols on YBT score improvements to establish optimal treatment parameters.

Despite several key findings, this study has certain limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and participants were confined to a narrow age range, which may have influenced the results. Future research should consider larger, more demographically diverse cohorts to further examine the effects of neurodynamic mobilization across different populations and age groups, thereby improving the generalizability of the findings. Regarding data collection, the VAS pain scale has inherent limitations, including subjectivity, limited granularity, and moderate repeatability, meaning measurement error cannot be fully excluded. Additionally, the intervention period was limited to eight weeks; future studies should consider longer follow-up durations to more comprehensively assess changes in relevant outcomes. Finally, this study primarily addressed functional recovery rather than structural alterations, and further investigations are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of neurodynamic mobilization on the knee joint.

Neurodynamic mobilization effectively alleviates pain in patients with mild post-traumatic knee osteoarthritis, improves knee joint range of motion, enhances both static and dynamic balance, and promotes lower limb motor function.

We have acknowledged the university and the research department that facilitated the implementation of this research.

| 1. | Khella CM, Asgarian R, Horvath JM, Rolauffs B, Hart ML. An Evidence-Based Systematic Review of Human Knee Post-Traumatic Osteoarthritis (PTOA): Timeline of Clinical Presentation and Disease Markers, Comparison of Knee Joint PTOA Models and Early Disease Implications. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:1996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Courties A, Kouki I, Soliman N, Mathieu S, Sellam J. Osteoarthritis year in review 2024: Epidemiology and therapy. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2024;32:1397-1404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Duong V, Oo WM, Ding C, Culvenor AG, Hunter DJ. Evaluation and Treatment of Knee Pain: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:1568-1580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 172] [Article Influence: 57.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mason D, Englund M, Watt FE. Prevention of posttraumatic osteoarthritis at the time of injury: Where are we now, and where are we going? J Orthop Res. 2021;39:1152-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nuñez de Arenas-Arroyo S, Martínez-Vizcaíno V, Cavero-Redondo I, Álvarez-Bueno C, Reina-Gutierrez S, Torres-Costoso A. The Effect of Neurodynamic Techniques on the Dispersion of Intraneural Edema: A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:14472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Varangot-Reille C, Cuenca-Martínez F, Arribas-Romano A, Bertoletti-Rodríguez R, Gutiérrez-Martín Á, Mateo-Perrino F, Suso-Martí L, Blanco-Díaz M, Calatayud J, Casaña J. Effectiveness of Neural Mobilization Techniques in the Management of Musculoskeletal Neck Disorders with Nerve-Related Symptoms: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis with a Mapping Report. Pain Med. 2022;23:707-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lascurain-Aguirrebeña I, Dominguez L, Villanueva-Ruiz I, Ballesteros J, Rueda-Etxeberria M, Rueda JR, Casado-Zumeta X, Araolaza-Arrieta M, Arbillaga-Etxarri A, Tampin B. Effectiveness of neural mobilisation for the treatment of nerve-related cervicobrachial pain: a systematic review with subgroup meta-analysis. Pain. 2024;165:537-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reyes A, Aguilera MP, Torres P, Reyes-Ferrada W, Peñailillo L. Effects of neural mobilization in patients after lumbar microdiscectomy due to intervertebral disc lesion. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2021;25:100-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brophy RH, Fillingham YA. AAOS Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Management of Osteoarthritis of the Knee (Nonarthroplasty), Third Edition. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2022;30:e721-e729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tore NG, Oskay D, Haznedaroglu S. The quality of physiotherapy and rehabilitation program and the effect of telerehabilitation on patients with knee osteoarthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2023;42:903-915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ng WH, Jamaludin NI, Sahabuddin FNA, Ab Rahman S, Ahmed Shokri A, Shaharudin S. Comparison of the open kinetic chain and closed kinetic chain strengthening exercises on pain perception and lower limb biomechanics of patients with mild knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials. 2022;23:315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Åström M, Thet Lwin ZM, Teni FS, Burström K, Berg J. Use of the visual analogue scale for health state valuation: a scoping review. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:2719-2729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mohamed SHP, Alatawi SF. Effectiveness of Kinesio taping and conventional physical therapy in the management of knee osteoarthritis: a randomized clinical trial. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:2223-2233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Abed V, Kapp S, Nichols M, Castle JP, Landy DC, Conley C, Stone AV. Lysholm and KOOS QoL Demonstrate High Responsiveness in Patients Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Am J Sports Med. 2024;52:3161-3166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Karimijashni M, Sarvestani FK, Yoosefinejad AK. The Effect of Contralateral Knee Neuromuscular Exercises on Static and Dynamic Balance, Knee Function, and Pain in Athletes Who Underwent Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Single-Blind Randomized Controlled Trial. J Sport Rehabil. 2023;32:524-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | van Melick N, van der Weegen W, van der Horst N, Bogie R. Double-Leg and Single-Leg Jump Test Reference Values for Athletes With and Without Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Who Play Popular Pivoting Sports, Including Soccer and Basketball: A Scoping Review. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024;54:377-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Plisky P, Schwartkopf-Phifer K, Huebner B, Garner MB, Bullock G. Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Y-Balance Test Lower Quarter: Reliability, Discriminant Validity, and Predictive Validity. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2021;16:1190-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Peacock M, Douglas S, Nair P. Neural mobilization in low back and radicular pain: a systematic review. J Man Manip Ther. 2023;31:4-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rao RV, Balthillaya G, Prabhu A, Kamath A. Immediate effects of Maitland mobilization versus Mulligan Mobilization with Movement in Osteoarthritis knee- A Randomized Crossover trial. J Bodyw Mov Ther. 2018;22:572-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Sozlu U, Basar S, Semsi R, Akaras E, Sepici Dincel A. Preventive effect of the neurodynamic mobilization technique on delayed onset of muscle soreness: a randomized, single-blinded, placebo-controlled study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2025;26:464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Papacharalambous C, Savva C, Karagiannis C, Paraskevopoulos E, Pamboris GM. Comparative Effects of Neurodynamic Slider and Tensioner Mobilization Techniques on Sympathetic Nervous System Function: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Med. 2024;13:5098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cancela Á, Arias P, Rodríguez-Romero B, Chouza-Insua M, Cudeiro J. Acute effects of a single neurodynamic mobilization session on range of motion and H-reflex in asymptomatic young subjects: A controlled study. Physiol Rep. 2023;11:e15748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pietrosimone B, Lepley AS, Kuenze C, Harkey MS, Hart JM, Blackburn JT, Norte G. Arthrogenic Muscle Inhibition Following Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury. J Sport Rehabil. 2022;31:694-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Serrano-García B, Forriol-Campos F, Zuil-Escobar JC. Active Neurodynamics at Home in Patients with Knee Osteoarthritis: A Feasibility Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6635. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Weleslassie GG, Temesgen MH, Alamer A, Tsegay GS, Hailemariam TT, Melese H. Effectiveness of Mobilization with Movement on the Management of Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Res Manag. 2021;2021:8815682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mansfield CJ, Culiver A, Briggs M, Schmitt LC, Grooms DR, Oñate J. The effects of knee osteoarthritis on neural activity during a motor task: A scoping systematic review. Gait Posture. 2022;96:221-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Giorgino R, Albano D, Fusco S, Peretti GM, Mangiavini L, Messina C. Knee Osteoarthritis: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Mesenchymal Stem Cells: What Else Is New? An Update. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:6405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bittencourt JV, Corrêa LA, Pagnez MAM, do Rio JPM, Telles GF, Mathieson S, Nogueira LAC. Neural mobilisation effects in nerve function and nerve structure of patients with peripheral neuropathic pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0313025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Amirianfar E, Rosales R, Logan A, Doshi TL, Reynolds J, Price C. Peripheral nerve stimulation for chronic knee pain following total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review. Pain Manag. 2023;13:667-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sun J, Sun J, Shaharudin S, Zhang Q. Effects of plyometrics training on lower limb strength, power, agility, and body composition in athletically trained adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2025;15:34146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Plaza-Manzano G, Cancela-Cilleruelo I, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Cleland JA, Arias-Buría JL, Thoomes-de Graaf M, Ortega-Santiago R. Effects of Adding a Neurodynamic Mobilization to Motor Control Training in Patients With Lumbar Radiculopathy Due to Disc Herniation: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;99:124-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Danazumi MS, Nuhu JM, Ibrahim SU, Falke MA, Rufai SA, Abdu UG, Adamu IA, Usman MH, Daniel Frederic A, Yakasai AM. Effects of spinal manipulation or mobilization as an adjunct to neurodynamic mobilization for lumbar disc herniation with radiculopathy: a randomized clinical trial. J Man Manip Ther. 2023;31:408-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Chen R, Yin C, Hu Q, Liu B, Tai Y, Zheng X, Li Y, Fang J, Liu B. Expression profiling of spinal cord dorsal horn in a rat model of complex regional pain syndrome type-I uncovers potential mechanisms mediating pain and neuroinflammation responses. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Salniccia F, de Vidania S, Martinez-Caro L. Peripheral and central changes induced by neural mobilization in animal models of neuropathic pain: a systematic review. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1289361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Isenburg K, Mawla I, Loggia ML, Ellingsen DM, Protsenko E, Kowalski MH, Swensen D, O’Dwyer-Swensen D, Edwards RR, Napadow V, Kettner N. Increased Salience Network Connectivity Following Manual Therapy is Associated with Reduced Pain in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients. J Pain. 2021;22:545-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Norte GE, Solaas H, Saliba SA, Goetschius J, Slater LV, Hart JM. The relationships between kinesiophobia and clinical outcomes after ACL reconstruction differ by self-reported physical activity engagement. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;40:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/