Published online Oct 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i10.109822

Revised: June 18, 2025

Accepted: September 1, 2025

Published online: October 18, 2025

Processing time: 146 Days and 13.7 Hours

We aimed to translate and culturally adapt the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire for use in the Netherlands. The LIMB-Q Kids is a patient-reported outcome measure designed to assess functional, psychosocial, and aesthetic aspects of living with a limb difference in paediatric populations.

To investigate the feasibility of a questionnaire in the Netherlands, which was translated into Dutch after having already been successfully translated and vali

The translation and adaptation process followed best practice guidelines, in

The rigorous process resulted in a linguistically and conceptually equivalent Dutch version of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire. While some challenges were encountered, no major difficulties were reported. The constructs and cultural relevance were found to be relatable to the Dutch context. Minor adjustments were made based on patient feedback, such as clarifying questions and modifying translations for technical terms.

We demonstrated the successful translation and cultural adaptation of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire for use in the Netherlands. By following best practices, the researchers have developed a version that is conceptually and linguistically equivalent to the original English version. The availability of this Dutch version will facilitate the assessment of outcomes in paediatric populations with limb differences, and potentially enable cross-cultural comparisons.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates the successful translation and cultural adaptation of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire for use in the Netherlands. By following best practices, the researchers have developed a version that is conceptually and linguistically equivalent to the original English version. The availability of this validated Dutch version enhances the ability to assess patient-reported outcomes, supports cross-cultural research and comparisons, and can support improvement of patient-oriented pediatric orthopedic clinical care.

- Citation: Kessling LM, Voorn VM, Bessems JH, Cooper AP, Chhina H, Tolk JJ. Dutch translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire. World J Orthop 2025; 16(10): 109822

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i10/109822.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i10.109822

Deformities of the lower extremities consist of a broad spectrum, including deficiencies, joint abnormalities, and longitudinal deformities. These conditions can be of either congenital or acquired etiology. It is known that lower limb deformities can considerably impair self-perceived appearance gait and functional participation[1-3]. Overall health-related quality of life of these children is often negatively influenced due to the deformity and morbidity of surgical treatment[4]. To gain a comprehensive understanding of the impact of deformities and corrective interventions on patients, it is important to consider outcome measurements that go beyond assessing structural deformity in physical health[5-7]. Therefore, it is crucial to have a comprehensive and validated patient-reported outcome measure specific to the disease, addressing the concerns that are most important to patients[6,7].

Since a patient-reported outcome measure designed for a paediatric and adolescent population with lower limb differences was not available[5,6], some studies developed the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire[8,9]. In a meticulous development process, including patient and medical expert participation, the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire was developed[2,8]. The conceptual framework for the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire was developed through a rigorous process involving 79 cognitive interviews in an international population of children with a wide variety of lower limb deformities and their parents[2,9]. Subsequently, the content validity was established through 40 additional cognitive interviews with patients, parents, and experts who reviewed a preliminary version of LIMB-Q Kids[9]. The current version of the questionnaire comprises 159 items across 11 scales, each measuring a distinct concept relevant to health-related quality of life in this patient population[9]. For further development and to optimize international applicability an international field test is conducted[8]. To establish cross-cultural applicability and equivalence in measurement adequate translation and cross-cultural validation of questionnaires is essential. Therefore, our aim was to translate and culturally adapt the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire for use in Dutch-speaking populations.

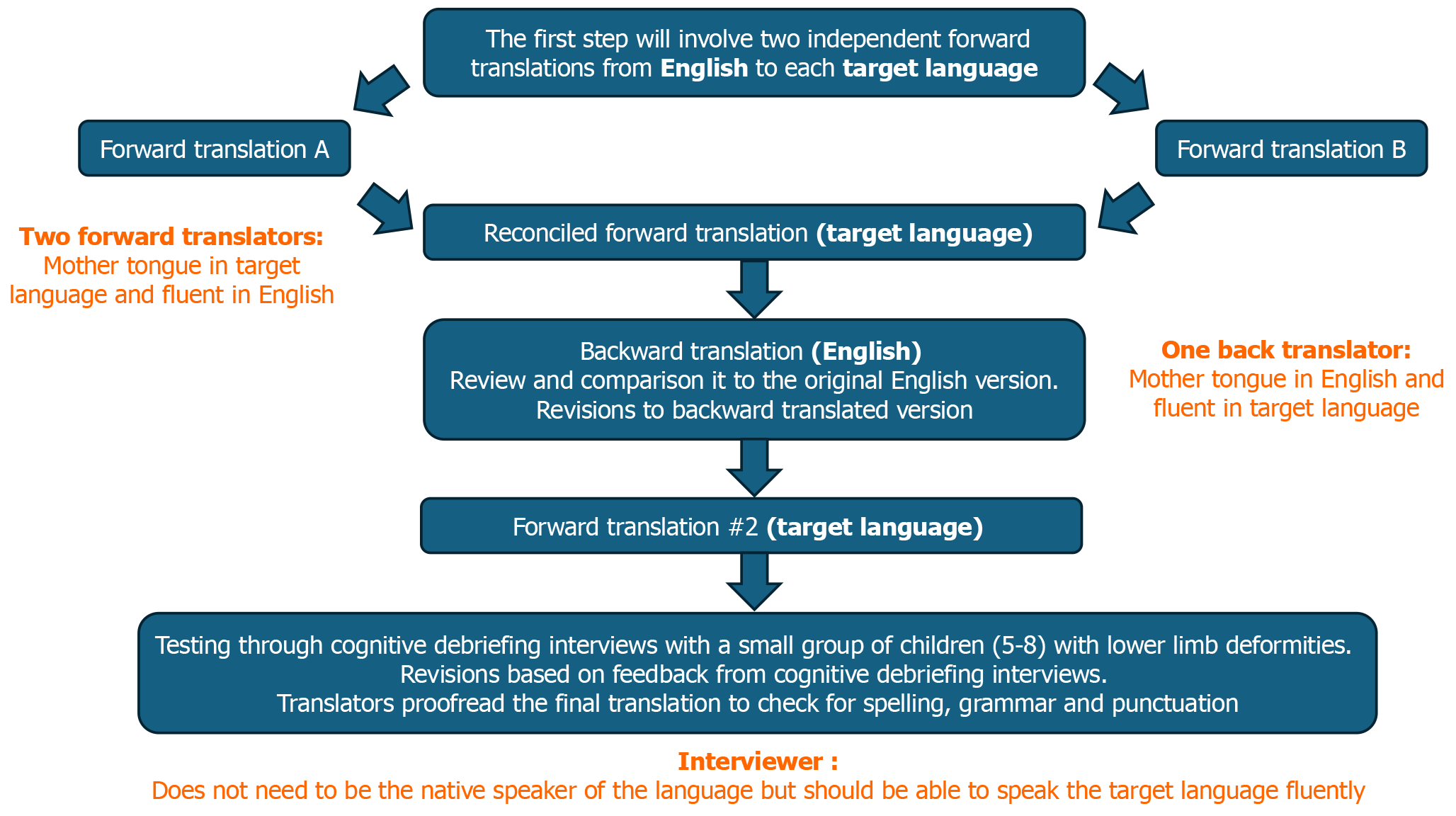

To ensure the accuracy and validity of the Dutch version of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire, a comprehensive translation and cross-cultural adaptation process was conducted. This process adhered to the clear guidelines outlined by the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (Figure 1)[10]. Prior to the commencement of the study, the necessary approval from the Ethics Committee of Erasmus University Medical (Approval No. MEC-2023-0402). Informed consent was obtained from all participating children and their parents. The original English version of LIMB-Q Kids was obtained from the developers (Chhina H and Cooper AP). The forward-translation phase involved two independent translations from English to Dutch by certified translators fluent in both languages, with Dutch as their mother tongue. They ensured the items retained their intended meaning and were understandable for the target paediatric population. The translators and study team (including developers of the original English version) then held a reconciliation meeting to reach consensus on the first Dutch version of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire. This initial translation underwent back-translation by a certified translator with Dutch as their native language and English fluency. This back-translated English version was compared with the original English version. Any discrepancies were noted and discussed within the study team, leading to a harmonized second Dutch version.

This version was used in the cognitive debriefing interviews (CDIs) with a diverse group of Dutch-speaking children with lower limb differences, aged 8-18 years with Dutch as their first language. CDIs were conducted either face-to-face or through a secure video link. Purposive sampling was applied to ensure a heterogenous sample regarding age, underlying diagnosis, and treatment type. Patients with cognitive disorders affecting their ability to read and write independently and patients with isolated joint disorders were excluded. CDIs followed a semi-structured interview guide (provided by the Q-Portfolio team). Interviewed participants provided feedback on the understandability and clarity of the instructions, response options, and items. Probing techniques including re-phrasing and specific questions to explore the participants’ understanding of the content and meaning of each item. An iterative process was followed, with the study team analyzing the interview results and making revisions based on participant suggestions. Interviews continued until no new issues were identified. Finally, the research team convened to review and revise the translation based on the feedback and suggestions provided during the CDIs. The final Dutch version of LIMB-Q Kids was then thoroughly proofread by the study team to ensure accuracy in spelling, grammar, and punctuation.

A total of 10 patients with a lower limb difference were interviewed (Table 1). Throughout the study we have docu

| Patient number | Age at interview (years) | Sex | Diagnosis | Type of treatment | Stage of treatment at the time of interview |

| 1 | 12 | Female | Idiopathic limb length difference | Shoe raise | Ongoing |

| 2 | 13 | Female | Fibula hemimelia | Guided growth surgery | Guided growth and ongoing; lengthening |

| 3 | 13 | Female | Valgus alignment and limb length difference following developmental dysplasia of hip | Guided growth surgery and distal femur epiphysiodesis | Ongoing |

| 4 | 10 | Female | Transversal reduction defect | Symes amputation, epiphysiodesis; prosthesis | Surgical interventions finished; prosthesis ongoing |

| 5 | 8 | Female | Idiopathic valgus deformity | Conservative | No intervention |

| 6 | 9 | Male | Posttraumatic growth arrest tibia | Leg lengthening, unilateral external fixator | Lengthening ongoing |

| 7 | 11 | Female | Congenital hip dislocation, leg length difference | Pelvic osteotomies and femur osteotomy | Finished |

| 8 | 10 | Male | Hemi-hypertrophy (Beckwidth-Wiedeman) | Planned epiphysiodesis | Planned |

| 9 | 13 | Female | Congenital torsional deformity femur | Planned for derotation osteotomy | Awaiting surgery |

| 10 | 9 | Male | Posteromedial bowing of the tibia | Leg lengthening with ring fixator and hemi-epiphysiodesis | During lengthening |

| Name of scale | Item (English original version) | Forward translation | Problem in forward translation | Backward translation | Expert panel opinion | Cognitive debriefing interviews |

| Knees symptoms | My knee is swollen or puffy | Gezwollen of opgezet1; Opgezwollen2 | At reconciliation meeting decided: ‘dik of opgezwollen’ | ‘My knee is thick or swollen’ | Backward translation is not literally identical, but Dutch phrasing is best option to capture the intended meaning | No concerns raised |

| Leg-related distress | I get upset when my leg stops me from having fun | Ik raak van slag1; Ik raak van streek2 | At reconciliation meeting decided ‘ik vind het vervelend’ | ‘I don’t like it when people look at my leg’ | Double negative should be avoided, but was only present in the back translation and not in the Dutch translation | No concerns raised |

| Hip symptoms | My hip hurts when it makes sound (clicks or pops) | Mijn heup doet pijn als hij geluid maakt (klikt of plopt)1,2 | No remarks | ‘My hip hurts when it makes a noise (when it clicks or pops)’ | Not identical, but similar meaning | Interviewed children suggested ‘klikt of knakt’ as a more relatable option, which we followed. This was well received in following CDIs |

| Physical function | … walk without a limp? | … lopen zonder mank te lopen?1; … zonder hinken te lopen?2 | Both were not well-flowing formulations, decided to go for: ‘… lopen zonder strompelen?’ | ‘… walk without stumbling?’ | We changed translation to ‘… lopen zonder hinken of manken?’ considering the backward translation this stays closest to the original ‘limp’ | The chosen translation was not deemed adequate by several interviewees, especially the word ‘hinken’ was flagged. Suggestions from patients were sought and finally ‘lopen zonder mank te lopen’ was chosen. In subsequent CDIs this was confirmed to be an adequate translation |

Two professional translators each made an independent translation of the LIMB-Q Kids. At the reconciliation meeting the majority of discrepancies in translation were minor, derived from synonyms or paraphrases. Consensus was easily reached on most items by selecting the translation choices that were easiest to read and had a lower reading level. Fourteen unique items (21 considering repetitive phrases) required more in-depth discussion at the reconciliation meeting. The purpose of these discussions was to ensure that the translated items accurately conveyed their intended meaning, were culturally appropriate, and were easily comprehensible for children in the target population. Examples of issues that were tackled are presented here.

For one item both translations were deemed linguistically accurate, but both had a slightly too high reading level for the intended audience: ‘I get upset’ was translated to ‘ik raak van slag’ by translator 1 and as ‘ik raak van streek’ by translator 2. In the reconciliation meeting it was decided to translate as ‘ik vindt het vervelend’, as this does capture the intended message of the original version and is easier to read. The team also discussed the translation of ‘happy’ because it could be literally translated as either ‘gelukkig’ or ‘blij’, which have slightly different nuances. ‘Gelukkig’ connotes a more permanent, deep-rooted sense of happiness, while ‘blij’ suggests a more temporary, in the moment feeling of joy or delight. Since the question aimed to explore the patient’s current opinion and day-to-day feelings, and considering ease of comprehension, the team decided ‘blij’ would best convey the intended meaning. Following the same consensus process, all discrepancies were resolved, and a preliminary Dutch translation was formulated.

After comparing the backward translation of the first Dutch version with the original English version, a total of 25 changes were identified. Out of these 25 corrections, 17 were minor modifications repeated in multiple instructions. The most important backward translation issues that were thoroughly explored in the expert panel meeting are presented here. The initial translation of ‘walking with a limp’ as ‘strompelen’ translated back to ‘stumbling’, which did not accurately convey the original meaning. During the expert panel meeting, the team struggled a bit to find a more appropriate alternative. Ultimately, they decided on ‘hinken of manken’ and flagged this as a specific item to discuss the word choice with children in the interview phase.

In some cases, the typical Dutch way of phrasing a certain sensation was not captured by the literal backward translation. For example: ‘My leg feels tingly (pins and needles feeling)’ translates as ‘mijn been slaapt’; the exact similar meaning intended by the question in English. The literal backward translation ‘my leg sleeps’ was inconsistent with the original English phrase but could thus be ignored. Another translated term that required further discussion was the translation of ‘i get upset’. In the Dutch translation it was phrased as ‘ik vind het vervelend’, which translated back to ‘i don’t like’. Because double negatives are cognitively challenging for children to process, in the original English version such phrases were specifically avoided. Nevertheless, in the Dutch phrasing this double negative was not present, some we maintained the original translation. Following the discussion and refinement of the various items, the expert panel concluded that the Dutch version exhibited semantic, experiential, and conceptual equivalence with the original English version and was ready to be used in CDIs.

Overall, patients found the instructions, response options, and items of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire to be clear and comprehensible. Relevant topics of discussion mentioned by patients included difficulty with technical terms like ‘orthosis’ and ‘brace’ for some. However, all patients who used such a device recognized and understood the terminology. Therefore, we decided not to change or further explain these terms. The translation for ‘limp’ was already flagged as difficult in earlier translation versions (‘hinken/manken’) and therefore specifically addressed in the interviews. Suggestions from patients were sought and several were given. ‘Lopen zonder mank te lopen’ was recommended by 3 patients, and all subsequent interviewees agreed on the adequacy of this translation. Therefore, this was implemented in the final version.

Furthermore, some minor adaptations were made based on interviewee suggestions. The difference between two subsequent questions on stair walking was clarified by underlining the words ‘ascending’ or ‘descending’. Another change was suggested for the description of a joint’s movement; ‘click or pop’ was initially translated as ‘klikt of plopt’, but interviewed children suggested ‘klikt of knakt’ as a more relatable option, which we followed. A final change was made to the translation of ‘other people’, initially translated as ‘anderen’, but as suggested by 1 child and confirmed by subsequent interviewees, ‘andere mensen’ was a better option to understand in this context. Additionally, this more closely resembles the original wording, so the change was adopted. After the above changes had been incorporated into the translation, no new items were flagged by subsequent interviewed children. Following proofreading by the research team, the final version of the Dutch LIMB-Q Kids was formulated.

We aimed to translate and culturally adapt the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire into Dutch, adhering to best practice guidelines[10]. The rigorous process resulted in a linguistically and conceptually equivalent Dutch version of the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire. Overall, while there were some challenges in selecting the most appropriate Dutch phrases to capture the meaning of the original version, no major difficulties were encountered. The constructs measured and cultural relevance of the activities and specific complaints mentioned in the survey were relatable to the Dutch context. This is likely due to the original LIMB-Q Kids instrument being designed for cross-country and cross-cultural applicability, and the fact that socioeconomic and healthcare standards do not vastly differ between the country of development and the Netherlands.

To account for the diversity in limb deformities, ages, treatment types, and treatment stages, we chose to conduct 10 CDIs, exceeding the minimum of 5 interviews suggested by International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research[10]. The results of these interviews indicate that the translation and cultural adaptation process was successful, with only minor changes needed after the initial rounds of translation and expert review. Nevertheless, despite the study being conducted in the highly multicultural Rotterdam area, the patient selection within this single geographic region poses a risk of not fully representing the dialectal variations across the country. Richer data might have been obtained by including a more diverse linguistic group in the cognitive debriefing[11]. It also should be noted that, during patient selection, data on ethnic background or socioeconomic status were not collected. However, since all patients were recruited at Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam - an expert center located in a large multicultural European city, that receives referrals from across the country - it can be considered likely that the selected sample represented a heterogeneous group in terms of socioeconomic background, dialect, and ethnicity. Nevertheless, it would be advisable for future studies of this kind to systematically collect such demographic information.

A clear limitation of the current version of the LIMB-Q Kids is its length, with 159 items[9]. This may lead to reduced concentration and willingness to thoroughly read each question towards the end of the questionnaire[12]. An international field test and psychometric testing, underway to enable future item reduction (including Rasch analysis). Moreover, the LIMB-Q Kids is designed for independent use of each sub-scale, providing flexibility in selecting only the most relevant sub-scales based on clinical and/or research needs[9].

We describe the rigorous process of translating and culturally adapting the LIMB-Q Kids questionnaire for use in the Netherlands. By adhering to best practices guidelines, we have developed an equivalent Dutch version that is conceptually and linguistically faithful to the original. The availability of this Dutch version will facilitate the assessment of outcomes in paediatric populations with limb differences, and potentially enable cross-cultural comparisons.

We would like to thank the Q-Portfolio team for sharing the guide for Translation and Cultural Adaptation.

| 1. | Michielsen A, van Wijk I, Ketelaar M. Participation and health-related quality of life of Dutch children and adolescents with congenital lower limb deficiencies. J Rehabil Med. 2011;43:584-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chhina H, Klassen AF, Kopec JA, Oliffe J, Iobst C, Dahan-Oliel N, Aggarwal A, Nunn T, Cooper AP. What matters to children with lower limb deformities: an international qualitative study guiding the development of a new patient-reported outcome measure. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2021;5:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gordon JE, Davis LE. Leg Length Discrepancy: The Natural History (And What Do We Really Know). J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39:S10-S13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montpetit K, Hamdy RC, Dahan-Oliel N, Zhang X, Narayanan UG. Measurement of health-related quality of life in children undergoing external fixator treatment for lower limb deformities. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29:920-926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Amakoutou K, Liu RW. Current use of patient-reported outcomes in pediatric limb deformity surgery. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2021;30:399-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Laubscher M, Nieuwoudt L, Marais LC. Effect of Frame and Fixation Factors on the Incidence of Pin Site Infections in Circular External Fixation of the Tibia. J Limb Lengthening Reconstr. 2022;8:24-30. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Theunissen WWES, Van der Steen MC, Van Veen MR, Van Douveren FQMP, Witlox MA, Tolk JJ. Strategies to optimize the information provision for parents of children with developmental dysplasia of the hip. Bone Jt Open. 2023;4:496-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chhina H, Klassen A, Kopec JA, Oliffe J, Cooper A. International multiphase mixed methods study protocol to develop a patient-reported outcome instrument for children and adolescents with lower limb deformities. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chhina H, Klassen A, Bade D, Kopec J, Cooper A. Establishing content validity of LIMB-Q Kids: a new patient-reported outcome measure for lower limb deformities. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:2805-2818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, Erikson P; ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Principles of Good Practice for the Translation and Cultural Adaptation Process for Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO) Measures: report of the ISPOR Task Force for Translation and Cultural Adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3263] [Cited by in RCA: 3480] [Article Influence: 165.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Collins JA, Lewin S, Shmueli-Blumberg D, Hoffman KA, Terashima JP, Korthuis PT, Horigian VE. The process and challenges of language translation and cultural adaptation of study instruments: a case study from the NIDA CTN CHOICES-2 trial. J Ethn Subst Abuse. 2023;22:417-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aiyegbusi OL, Cruz Rivera S, Roydhouse J, Kamudoni P, Alder Y, Anderson N, Baldwin RM, Bhatnagar V, Black J, Bottomley A, Brundage M, Cella D, Collis P, Davies EH, Denniston AK, Efficace F, Gardner A, Gnanasakthy A, Golub RM, Hughes SE, Jeyes F, Kern S, King-Kallimanis BL, Martin A, McMullan C, Mercieca-Bebber R, Monteiro J, Peipert JD, Quijano-Campos JC, Quinten C, Rantell KR, Regnault A, Sasseville M, Schougaard LMV, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh R, Snyder C, Stover AM, Verdi R, Wilson R, Calvert MJ. Recommendations to address respondent burden associated with patient-reported outcome assessment. Nat Med. 2024;30:650-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/