Published online Oct 18, 2025. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v16.i10.109095

Revised: June 4, 2025

Accepted: September 1, 2025

Published online: October 18, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 18.7 Hours

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) is a rare autoinflammatory bone disorder primarily affecting children and adolescents. Spinal involvement in CRMO is common and can lead to significant clinical features and complications, including severe chronic back pain and spinal deformities with possible spinal cord compression.

To summarize the information about vertebral involvement in CRMO patients, including the clinical features, diagnostic approaches, and treatment outcomes.

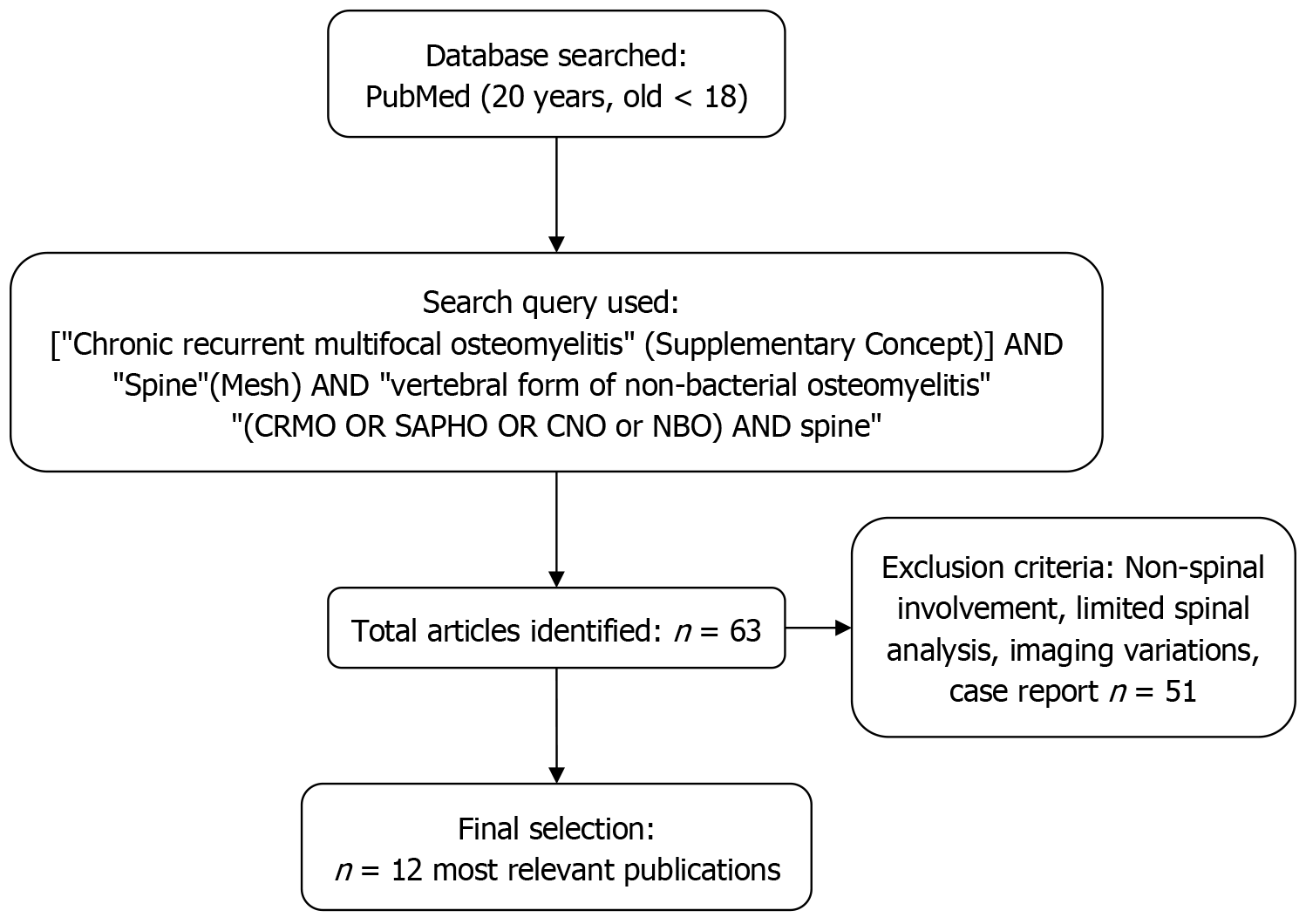

Sixty-three manuscripts (2005-2025) were found in PubMed, including case re

Spinal involvement in CRMO ranges from 28% to 81% among patients with CRMO. Patients typically present with localized back pain, back stiffness, and, in more severe cases, spinal deformities such as kyphosis or scoliosis. Multifocal lesions are frequently observed, with the thoracic spine being the most commonly affected area. Whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI) has emerged as the gold standard for effectively revealing multifocal bone lesions and spinal involvement. However, a bone biopsy is often needed to rule out infection or malignancy. Bisphosphonate treatment showed a high response rate (90.9%), while tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors were less effective (66.7%). Long-term follow-up is crucial, as relapses and pro

Spinal involvement in CRMO often leads to chronic pain, vertebral deformities, and rare spinal deformities. Early diagnosis using WBMRI, combined with treatment with bisphosphonates and TNF-α inhibitors, could improve outcomes.

Core Tip: Non-bacterial osteomyelitis with vertebrae involvement has differences not only in clinical and laboratory features but also in the effectiveness of therapeutic options. The literature on this issue is extremely scarce, mainly focusing on the diagnostic and imaging features of the disease. The analysis of 63 publications (2005-2024) selected by the keywords "chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis", "spine", "vertebral form of non-bacterial osteomyelitis", and "SAPHO" is presented. The researchers' consensus emphasizes the variety of radiation manifestations, the need to integrate whole-body magnetic resonance imaging into the diagnostic algorithm, the possibility of spinal complications (including spinal deformities and neurological complications), and the step-by-step principle of treatment, with a recommendation to include bisphosphonates in the first line of therapy.

- Citation: Petukhova VV, Maletin AS, Mushkin AY, Kostik MM. Spinal involvement in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis - diagnostics, treatment and what remains in the shadows: A literature review. World J Orthop 2025; 16(10): 109095

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v16/i10/109095.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v16.i10.109095

Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO), also known as chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis (CNO), is a rare autoinflammatory bone disease that primarily affects children and adolescents. Recurrent episodes of bone inflammation characterize the condition without an infectious cause, often leading to pain, swelling, and, in some cases, structural bone damage[1]. Spinal involvement in CRMO presents distinct clinical challenges and complications, including vertebral fractures and structural orthopedic deformities such as kyphosis and scoliosis[2,3].

CRMO can be challenging to diagnose due to its nonspecific symptoms, which overlap with infectious osteomyelitis, malignancies, and other inflammatory disorders[4,5]. Advanced imaging modalities, particularly whole-body magnetic resonance imaging (WBMRI), have significantly improved diagnostic accuracy by detecting multifocal lesions and assessing disease severity[6]. However, a standardized approach to diagnosis and treatment remains elusive due to the variability in clinical presentation and disease progression.

Our study aimed to summarize the clinical features, diagnostic challenges, and treatment outcomes of CRMO with spinal involvement. These aspects are crucial for enhancing early diagnosis, refining management strategies, and mitigating long-term complications in affected children.

A literature study search strategy was conducted in the PubMed database using the query: ["Chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis" (Supplementary Concept)] AND "Spine"(Mesh) AND "vertebral form of non-bacterial osteomyelitis", "(CRMO OR SAPHO OR CNO or NBO) AND spine" with search depth 20 years (Figure 1). Sixty-three publications were found and analyzed, including case reports, retrospective cohort studies, randomized controlled trials, and imaging studies. The earliest study was published in 2005. The 13 studies (2008-2024) most relevant publications were chosen for the final analysis.

The publications focus on the epidemiology of spinal involvement, diagnostic imaging, treatment strategies, and long-term outcomes in pediatric CRMO patients (Table 1)[1-12].

| Ref. | Year | Journal type | Publication type | Country of study | Patient's age group (age range) | Main topic (total patients) | Vertebral cases | Treatment | Complications | Specific issues addressed |

| Hospach et al[1] | 2010 | Eur J Pediatr | Retrospective cohort | Germany | Pediatric | 102 | 27 | Pamidronate | Vertebral deformities | Treatment response, MRI outcomes |

| Rogers et al[2] | 2024 | Pediatric Orthopedics | Original research | United States | Children, adolescents (approximately 4–18 years) | Spine involvement, vertebral deformities (170) | 48 (27-vertebral bodies) | NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, biologics | Kyphosis, scoliosis, pain | Vertebral deformities and treatment outcomes |

| Guariento et al[3] | 2023 | Pediatric Radiology | Original research | Italy | Children (pediatric; not explicitly stated) | MRI findings in spinal CRMO | Not specified (imaging focus) | Not discussed | MRI features of spinal lesions | |

| Gleeson et al[4] | 2008 | J Rheumatol | Retrospective cohort | Australia | 5-14 years | 7 | 5 | Pamidronate | Vertebral fractures, kyphosis | Radiological improvement |

| Shah et al[5] | 2022 | Clinical Imaging | Review/imaging feature | United States | Children (pediatric, not specified) | Radiological differentiation of CRMO | Not specified (diagnostic focus) | Not specified | Imaging pitfalls and differentiation from infection/malignancy | |

| Andronikou et al[6] | 2020 | Rheumatology | Review article | United States, United Kingdom | Children (pediatric) | Role of WBMRI in CRMO | Not specified (imaging focus) | Not discussed | Importance of WBMRI for diagnosis | |

| Wipff et al[7] | 2015 | Rheumatology | Cohort study | France | Pediatric/adolescent | Disease characteristics (178) | 40 | NSAIDs, immunomodulators | Persistent disease activity | Clinical course, complications |

| Guérin-Pfyffer et al[8] | 2012 | Joint Bone Spine | Retrospective study | France | 8-14 years | 9 | 4 | NSAIDs, pamidronate | Pain | MRI, clinical follow-up |

| Galeotti et al[10] | 2015 | Pediatric Radiology | Original research | France | Children (pediatric) | Vertebral fractures on MRI | Not specified | Vertebral collapse, pain | Detection of vertebral fractures via WBMRI | |

| Andreasen et al[11] | 2019 | Rheumatology | Original research | Denmark | Children, adolescents (mean approximately 10.7 years; 9.9–11.4) | Treatment outcomes in chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis/CRMO (51 patients) | 13 | NSAIDs, pamidronate, TNF-α inhibitors | Persistent pain, structural deformity | Effectiveness of early bisphosphonate treatment |

| Kostik et al[12] | 2020 | Rheumatology | Original research | Russia | Children (pediatric, not explicitly stated) | Treatment outcomes in spinal CRMO | 29 | NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, TNF inhibitors | Kyphosis, vertebral compression, chronic inflammation | Treatment response in spinal involvement |

| Chong et al[9] | 2014 | Rheumatology | Imaging study | South Korea | Pediatric/adolescent | Nuclear medicine imaging (unspecified) | NSAIDs | None specified | Positron emission tomography/computed tomography imaging variability |

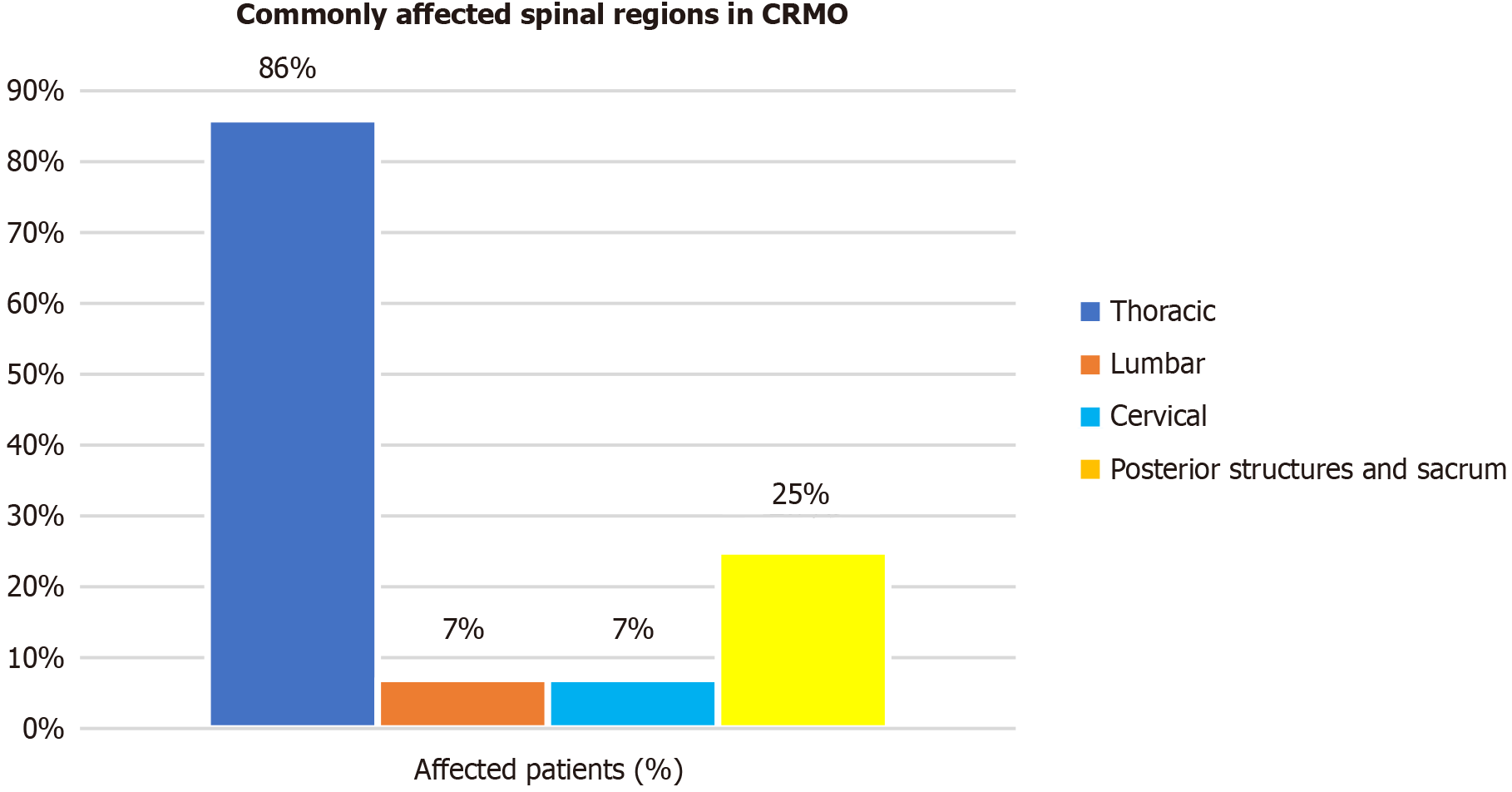

Spinal involvement in CRMO is increasingly recognized as a significant concern, with prevalence rates ranging from 28% to 81%[2,3]. According to data from a large national cohort of French patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis, clinical spinal lesions were observed in 32.5% of patients, of which 17.5% had spinal fractures[7]. According to a Russian study (Kostik et al[12]), the incidence of spinal cord injury in non-bacterial osteomyelitis (NBO) is 31.9%. The differences in the purity of spinal lesions across various studies are due to the diagnostic methods used, including WBMRI. The most commonly affected regions are the thoracic spine, followed by the lumbar and cervical ones (Figure 2)[3].

Patients with spinal CRMO often present with localized back pain, stiffness, and reduced mobility, though some may remain asymptomatic, with lesions discovered incidentally on screening WBMRI. In more severe cases, vertebral compression, described as "fractures", can lead to spinal deformities, including kyphosis and scoliosis, which can develop into long-term musculoskeletal complications[4,9].

The diagnosis for spinal CRMO remains complex (laboratory and visualization) due to its overlapping symptoms with infectious osteomyelitis, malignancies, and other inflammatory disorders[5]. WBMRI has emerged as the gold standard for detecting multifocal bone lesions and assessing spinal involvement, allowing for earlier and more accurate diagnoses[6,10]. However, despite the usefulness of imaging, histopathological confirmation is sometimes necessary to rule out infection or malignancy, although the findings are often nonspecific[8].

Most publications[3,5,6,10] are dedicated to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the diagnosis of spinal CRMO, underscoring the pivotal role of imaging in diagnosis and longitudinal disease monitoring. The studies emphasize the value of WBMRI as a noninvasive and highly sensitive technique for detecting multifocal skeletal involvement and determining the extent of inflammatory activity[6]. Guariento et al[3] and Shah et al[5] provide detailed analyses of specific MRI features such as vertebral bone marrow edema, irregularity of endplates, and loss of vertebral height-hallmarks that assist in distinguishing CRMO from differential diagnoses, including infectious spondylodiscitis and malignancies. Galeotti et al[10] investigated the relationship between radiological abnormalities and clinical outcomes, finding that vertebral fractures detected on MRI frequently correlate with long-term structural deformities, underscoring the importance of timely and accurate imaging to inform early intervention. Together, these findings support the routine use of standardized imaging protocols in clinical practice, particularly WBMRI, for initial diagnostic workups and ongoing assessments. Moreover, interpreting subtle imaging markers requires experienced musculoskeletal radiologists to ensure diagnostic accuracy, especially in early or atypical cases. Beyond diagnosis, imaging serves as a critical tool in evaluating therapeutic efficacy. Serial MRIs enable clinicians to monitor lesion regression, persistence, or progression, informing treatment escalation or tapering decisions. Thus, MRI continues to represent a cornerstone in the multidisciplinary management of spinal CRMO, bridging diagnostic clarity with treatment planning and outcome monitoring.

In more than 80% of cases, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used at the first symptoms of the disease. They usually reduce focal inflammation and pain[12]. For patients with spinal CRMO, bisphosphonate therapy has demonstrated high efficacy and is the first-line therapy, with response rates of up to 90.9%[11]. In the context of spinal lesions, outcomes are particularly notable. Hospach et al[1] analyzed children with CRMO-related vertebral involvement among those treated with pamidronate (all of whom had vertebral deformities and pain). Every patient achieved complete pain resolution within three months, and follow-up MRIs at approximately one year showed partial or com

Additionally, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors have been successful in 66.7% of cases, particularly in patients with refractory CRMO[4]. In a large French cohort, Wipff et al[7] reported that 89% of patients treated with

Both TNF-α inhibitors and bisphosphonates have become mainstays for treating cases of CRMO that are difficult to manage, particularly those with spinal involvement, and their use is often tailored to individual patient needs. TNF-α blockers are beneficial when systemic inflammation is prominent or when concurrent autoimmune features are present, offering broad anti-inflammatory effects and high remission rates.

Bisphosphonates, on the other hand, directly strengthen bone and are invaluable for preventing vertebral collapse and relieving intractable bone pain. Notably, these therapies are not mutually exclusive–in some refractory cases, combination therapy (TNF-α inhibitor and bisphosphonate) has yielded robust disease control when either modality alone was insufficient. Ultimately, the effectiveness of any treatment in spinal CRMO is assessed through a combination of patient-reported outcomes and objective measures: (1) The absence of new lesions or flares; (2) Restoration of normal inflammatory marker levels; (3) Preservation (or improvement) of vertebral body height on imaging; and (4) The resolution of bone marrow edema on MRI accompanied by the child's return to a pain-free, active life. Continued research (including prospective trials and standardized treatment plans)[1,2,4,5,7] is anticipated to refine these therapies further, but current evidence affirms that both TNF-α inhibitors and bisphosphonates are effective interventions that significantly improve clinical and radiological outcomes in children with spinal CRMO[8,10,11].

In general, the summarized data concerning current knowledge about spinal involvement in pediatric CRMO patients are as follows: (1) The frequency floats between 28%-81% of all CRMO cases; (2) The female sex was prevalent, with the prevalence age of patients between 4-18 years old; (3) The clinical features (according to the clinical evidence) are back pain, symptoms of inflammation, the rigidity of the spine, and spinal deformity; (4) The most informative study was whole-body MRI; (5) The thoracic spine is the most frequently involved spinal level (86%); (6) The posterior part of vertebrae (neural arch) and sacrum are involved in 25% of cases; (7) Cervical and lumbar vertebrae–in 7% for every zone; and (8) The conservative treatment includes NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, and TNF-α inhibitors with significant advantage of bisphosphonates.

NBO and CRMO represent closely related entities within a spectrum of autoinflammatory bone disorders. According to the provided literature, NBO refers broadly to sterile osteomyelitis without infectious etiology, encompassing both isolated and multifocal skeletal involvement[10,11]. On the other hand, CRMO specifically describes the chronic and recurrent presentation of NBO, characterized by multiple simultaneous or sequential inflammatory foci in bones. In clinical practice, these terms are often used interchangeably; however, the differentiation typically hinges on the number and chronicity of lesions. NBO can include solitary lesions that may not recur, presenting a more limited and often monophasic course. CRMO explicitly involves multiple lesions with a chronic and relapsing disease trajectory[7], frequently accompanied by systemic inflammatory manifestations and potential association with other autoinflammatory disorders, such as psoriasis or inflammatory bowel disease[1,6]. In research contexts, CRMO is frequently employed as the preferred terminology due to its precise emphasis on recurrent multifocal manifestations[7].

Spinal involvement in CRMO remains a multifaceted clinical challenge, as evidenced by the reviews[2,3,9]. The majority of publications focus on extensive noninvasive imaging, particularly WBMRI[3,5,6,9], and pharmacologic management with NSAIDs, bisphosphonates[1,2,4,5,7], and TNF-α inhibitors[8,10-12]. All demonstrated the improvement of the baseline patterns of the disease, vertebral deformities, and long-term outcomes[2]. However, several key questions remain inadequately addressed.

First, while the diagnostic value of imaging modalities is well-documented[6,10], there is a notable gap concerning predictive biomarkers that could facilitate the earlier differentiation of CRMO from infectious osteomyelitis, malignancies, or metabolic bone disorders. Specific molecular or serological markers remain largely unexplored, which limits the individual's ability to tailor treatment strategies. Additionally, the psychosocial impact of chronic spinal pain and functional limitations is underreported. None of the publications provide substantial data on quality-of-life measures, psychological distress, or the long-term socioeconomic effects of the disease, areas that could be critical for comprehensive patient management.

Second, there is a significant gap in the area of surgical procedures. Although severe cases with structural deformities may eventually require orthopedic intervention, the publications offer little to no data on surgical management (di

The evaluation in this analysis specifically did not separate children from adolescents nor include adults distinctly, based on several key considerations identified within the reviewed literature: (1) The reviewed publications frequently grouped children and adolescents due to the similarity in clinical presentation, radiological features, disease progression, and response to therapy across these age groups[7,10,11]; and (2) Adults with CRMO typically have different clinical manifestations and diagnostic challenges (e.g., Synovitis-Acne-Pustulosis-Hyperostosis-Osteitis syndrome)[6,7]. These cases often require distinct diagnostic criteria, treatment regimens, and assessment methods, thus warranting separate analyses outside the scope of this pediatric-focused review; pediatric and adolescent patients often follow unified treatment protocols (NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, TNF inhibitors), and the outcomes are assessed similarly, such as prevention of vertebral deformities, reduction of pain, and lesion resolution on imaging[10,11].

Spinal involvement in CRMO often leads to chronic pain, vertebral deformities, and rare spinal deformities. Early diagnosis using WBMRI and histopathological evaluation is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary interventions. Treatment with NSAIDs, bisphosphonates, and TNF-α inhibitors can improve outcomes, but long-term monitoring is necessary to manage relapses and prevent complications. While current literature has enriched our understanding of noninvasive diagnostic and pharmacological strategies for spinal CRMO, further research is needed to address long-term outcomes, establish predictive biomarkers, assess psychosocial impacts, and develop evidence-based guidelines for surgical intervention. These additional insights would significantly enhance personalized treatment approaches and improve patient care.

| 1. | Hospach T, Langendoerfer M, von Kalle T, Maier J, Dannecker GE. Spinal involvement in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO) in childhood and effect of pamidronate. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169:1105-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rogers ND, Trizno AA, Joyce CD, Roberts JL, Soep JB, Donaldson NJ. Spine Involvement and Vertebral Deformity in Patients Diagnosed with Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2024;44:561-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Guariento A, Sharma P, Andronikou S. MRI features of spinal chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis/chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis in children. Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53:2092-2103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gleeson H, Wiltshire E, Briody J, Hall J, Chaitow J, Sillence D, Cowell C, Munns C. Childhood chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis: pamidronate therapy decreases pain and improves vertebral shape. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:707-712. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Shah A, Rosenkranz M, Thapa M. Review of spinal involvement in chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis (CRMO): What radiologists need to know about CRMO and its imitators. Clin Imaging. 2022;86:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Andronikou S, Kraft JK, Offiah AC, Jones J, Douis H, Thyagarajan M, Barrera CA, Zouvani A, Ramanan AV. Whole-body MRI in the diagnosis of paediatric CNO/CRMO. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:2671-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wipff J, Costantino F, Lemelle I, Pajot C, Duquesne A, Lorrot M, Faye A, Bader-Meunier B, Brochard K, Despert V, Jean S, Grall-Lerosey M, Marot Y, Nouar D, Pagnier A, Quartier P, Job-Deslandre C. A large national cohort of French patients with chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67:1128-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guérin-Pfyffer S, Guillaume-Czitrom S, Tammam S, Koné-Paut I. Evaluation of chronic recurrent multifocal osteitis in children by whole-body magnetic resonance imaging. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79:616-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chong A, Ha JM, Hong R, Kwon SY. Variations in findings on (18) F-FDG PET/CT, Tc-99m HDP bone scan and WBC scan in chronic multifocal osteomyelitis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2014;17:344-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galeotti C, Tatencloux S, Adamsbaum C, Koné-Paut I. [Value of whole-body MRI in vertebral fractures]. Arch Pediatr. 2015;22:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Andreasen CM, Jurik AG, Glerup MB, Høst C, Mahler BT, Hauge EM, Herlin T. Response to Early-onset Pamidronate Treatment in Chronic Nonbacterial Osteomyelitis: A Retrospective Single-center Study. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:1515-1523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kostik MM, Kopchak OL, Maletin AS, Mushkin AY. The peculiarities and treatment outcomes of the spinal form of chronic non-bacterial osteomyelitis in children: a retrospective cohort study. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/