Published online Jun 10, 2017. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i3.261

Peer-review started: January 16, 2017

First decision: March 28, 2017

Revised: April 21, 2017

Accepted: May 18, 2017

Article in press: May 20, 2017

Published online: June 10, 2017

Processing time: 139 Days and 6.6 Hours

To study the levels of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

This was a non randomized case control study conducted at Department of Biochemistry, in collaboration with Regional Cancer Center over a period of one year. The study population included 50 adult newly diagnosed HNSCC patients reporting in outpatient department at Regional Cancer Center and compared with 50 healthy controls. NGAL was estimated by ELISA technique. Student t test and χ2 test were applied for comparison of means of study groups. Correlations between groups were analyzed using Pearson correlation coefficient (r) formula.

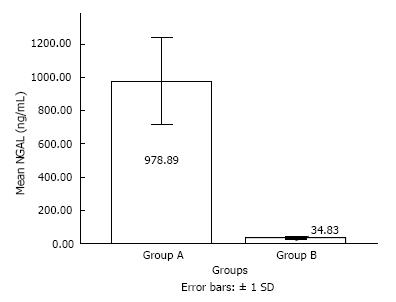

Patients with HNSCC exhibited significantly increased levels of NGAL (P < 0.05) as compared to healthy controls (978.88 ± 261.39 ng/mL vs 34.83 ± 7.59 ng/mL). Out of 50, 26 patients (52%) were in stage IV, 21 (42%) in stage III, 1 (2%) patient in stage II and 2 (4%) patients were in stage I. Metastasis was absent in 98% patients and mean NGAL levels were highest in these patients but P value was not significant. Mean NGAL levels were highest in stage IV [1041.54 ± 222.15 ng/mL (stage IV) vs 1040 ± 0.00 ng/mL (stage I); 900 ± 0.00 ng/mL (stage II) and 1031.90 ± 202.55 ng/mL (stage III)] and χ2 test was highly significant (P < 0.001). Thirty-six patients (72%) were having moderately differentiated HNSCC and mean NGAL levels were maximum in patients with well differentiated HNSCC (1164 ± 315.64 ng/mL vs 1013.33 ± 161.19 ng/mL in moderately differentiated and 890 ± 11.55 ng/mL in poorly differentiated) and the results were also highly significant (P < 0.001, χ2 test).

The present work demonstrates a potential role of NGAL as cancer biomarker and its use in monitoring the HNSCC progression.

Core tip: Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin might play a significant role as a biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

- Citation: Verma M, Dahiya K, Soni A, Dhankhar R, Ghalaut VS, Bansal A, Kaushal V. Levels of neutrophil gelatinase-assosciated lipocalin in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in Indian population from Haryana state. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 8(3): 261-265

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v8/i3/261.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v8.i3.261

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common cancer worldwide, affecting 600000 new patients each year. The molecular alterations observed in HNSCC are mainly due to oncogene activation and tumor suppressor gene inactivation, leading to dysregulation of cell proliferation. These alterations include gene amplification and over expression of oncogenes such as ras, myc, epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and cyclin D1 and mutations and deletions leading to p16 and TP53 tumor suppressor genes inactivation[1].

Neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) is a small molecule of 178 amino acids that belongs to the superfamily of lipocalins, which are proteins specialized in binding and transporting small hydrophobic molecules. It is also known as lipocalin 2, protumorigenic protein. Increased expression of NGAL was first identified in SV 40 tumour virus infected quiescent mouse primary kidney cells. It plays a significant role in inducing tumour progression and chemoresistance in cancer cells. It acts mainly as a biomarker of kidney injury but now a day it has emerged as a biomarker for several benign and malignant diseases[2]. Lipocalin 2 is thought to be an acute phase protein[3], the expression of which is upregulated in epithelial cells under diverse inflammatory conditions including appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease and diverticulitis[4]. Lipocalins affect cellular proliferation and differentiation and may be involved in the development of carcinomas[5].

Levels of lipocalin 2 is upregulated or downregulated in different cancers, i.e., lung, colon, pancreas, breast, prostate, etc[4,6-8]. But studies are scarce in head and neck carcinoma particularly with respect to its involvement in invasion and metastasis. Five year survival rate of HNSCC is only 50%[9]. Early diagnosis can improve the outcome. So, there is an urgent need for the development of novel biomarkers for timely diagnosis of this fatal disease. Therefore this study was planned to estimate NGAL levels in HNSCC.

This was a non randomized case control study conducted at Department of Biochemistry, in collaboration with Regional Cancer Center over a period of one year from September 2013 to September 2014. A total of 50 newly diagnosed patients were selected for the study. Group A consisted of 50 HNSCC patients and 50 apparently healthy age and sex matched volunteers acted as controls (Group B).

After taking care of all ethical issues, 12 h fasting venous blood samples without application of tourniquet were collected aseptically from median antecubital vein. Serum was separated and stored at -20 °C till analysis. Serum-NGAL was measured using ELISA (Bioporto, Gentofte, Denmark)[10].

Data was subjected to appropriate statistical analysis. Values are shown in the text, tables and figures as mean ± SD. Student t test and χ2 test were applied for comparison of means of study groups. A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant. Correlations between groups were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) formula.

The mean age of the patients in group A was 57.40 ± 11.33 years (35-95 years), while in group B was 40.01 ± 10.8 years (37-90 years). Out of 50 patients, 40 were males and 10 were females in group A while there were 38 males and 12 females in group B. Both the groups were statistically comparable in age and gender distribution. The biochemical parameters are shown in Table 1. Serum NGAL levels were significantly raised in HNSCC patients (P < 0.05) as compared to controls (978.88 ± 261.39 ng/mL vs 34.83 ± 7.59 ng/mL) (Figure 1).

| Parameter | HNSCC patients | Healthy controls |

| n | 50 | 50 |

| Age (yr) | 57.40 ± 12.61 | 40.01 ± 10.8 |

| Gender (M:F) | 40:10 | 38:12 |

| Smoker:non-smoker | 40:10 | 12:38 |

| Serum NGAL (ng/mL) | a978.88 ± 261.39 | 34.83 ± 7.59 |

Out of 50, 26 patients (52%) were in stage IV, 21(42%) in stage III, 1 (2%) patient in stage II and 2 (4%) patients were in stage I. Relation between NGAL and various study variables is shown in Table 2. Mean NGAL levels were highest in stage IV and χ2 test was highly significant (P < 0.001). Metastasis was absent in 49 patients (98%). Only 1 patient (2%) was having metastasis of unknown origin in head and neck area with occult primary. Results were not significant but mean NGAL levels were highest in patients with no metastasis. Ratio of smokers to non smokers in HNSCC patients was 40:10 while in controls it was 12:38. Smoking history seemed to have no effect on systemic levels of NGAL as P = 0.097. Thirty six patients (72%) were having moderately differentiated HNSCC and mean NGAL levels were maximum in patients with well differentiated HNSCC and the results were also highly significant (P < 0.001, χ2 test).

| n | Serum NGAL (mean ± SD) | |

| Differentiation | ||

| Well differentiated | 10 | 11164 ± 315.64 |

| Moderately differentiated | 36 | 1013.33 ± 161.19 |

| Poorly differentiated | 4 | 890 ± 11.55 |

| Site | ||

| Base of tongue | 18 | 11072.22 ± 251.39 |

| Larynx | 19 | 1037.89 ± 217.35 |

| Tonsil | 11 | 947.27 ± 50.02 |

| Cheeks | 2 | 1120 ± 0.00 |

| Metastasis | ||

| No | 49 | 1036.73 ± 206.64 |

| Yes | 1 | 880 ± 0.00 |

| Staging | ||

| I | 2 | 1040 ± 0.00 |

| II | 1 | 900 ± 0.00 |

| III | 21 | 1031.90 ± 202.55 |

| IV | 26 | 11041.54 ± 222.15 |

| Smoking | ||

| Smoker | 40 | 1051 ± 223.57 |

| Non-smoker | 10 | 964 ± 84.22 |

In our study larynx was the most common site involved (38%), other sites being base of tongue (36%), tonsils (22%) and cheek mucosa (4%). Serum NGAL values were significantly higher in patients with base of tongue involvement (P < 0.001, χ2 test).

Various studies have shown different levels of NGAL levels in many carcinomas, i.e., lung, colon, pancreas, breast, prostate, etc. But very few reports are available for head and neck cancer. A significant increase was observed in serum NGAL levels in HNSCC patients as compared to healthy controls (P < 0.05). Moreover, levels were significantly raised in stage IV (P < 0.001) and well differentiated HNSCC carcinoma patients (P < 0.001). Metastasis was absent in 98% patients and mean NGAL levels were highest in these patients showing anti-metastatic effect of NGAL. Majority of patients in our set up usually present in advanced stage of the disease due to lack of awareness or resources or both.

Previous studies have shown increased levels of NGAL in adenocarcinoma of lung, colon, pancreas and decreased levels in renal cell carcinomas and prostate cancers[11]. Role of NGAL in cancer is controversial. NGAL has been shown to have a pro-tumoral effect in breast, stomach and esophagus cancer. Some studies show that NGAL exert an anti-tumoral and anti-metastatic effect in ovarian and pancreatic cancers similar to present study[12]. These increased levels may be due to increased synthesis induced by factors promoting the development of carcinoma. NGAL and pro-matrix metalloprotein-9 (MMP-9) bind to integral membrane proteins on tumour cells and leads to pro or anti tumour effect on growth, migration, invasion, survival and angiogenesis depending on the type of cancer[13]. In vitro studies in human breast and lung cancer cells have revealed that NGAL expression is significantly up regulated in response to multiple apoptosis inducing agents in an attempt to survive the apoptotic stimulus rather than a pro-apoptotic response[14].

Metastasis was absent in 49 patients and an over expression of NGAL, as obvious by increased levels in all these. Only 1 patient was having metastasis of unknown origin in head and neck area. We assumed the primary center being head and neck site. So, it is assumed that over expressed NGAL levels are responsible for reduction in distant metastasis of HNSCC cells as seen in many other cancers also though nothing can be concluded as sample size being very small[15]. The mechanisms by which NGAL regulates tumor metastasis are still unclear. Down-regulation of epithelial proteins and the induction of mesenchymal proteins (EMT) enhance the metastatic potential of epithelial tumors.

Lipocalin 2 is an epithelial inducer, which stimulates the epithelial phenotype in ras transformed cells and reverses their metastatic potential[16]. NGAL has siderophore chelating capacity. It binds to intracellular iron and this complex then interacts with NGAL-R (NGAL receptor) leading to internalization of complex. After entering cytoplasm, it releases iron leading to iron accumulation and regulating specific iron-dependent genetic pathways. These events induce proliferation and epithelial transformation[17]. It inhibits focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation and vascular endothelial growth factor synthesis leading to decreased cell adhesion, invasion and angiogenesis[12]. NGAL also suppresses c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3)/AKT signalling pathways, thereby, decreasing metastasis in HNSCC[13].

Lipocalin 2 levels were significantly higher in well differentiated carcinoma as compared to moderately and poorly differentiated HNSCC (P < 0.001). Similar results have been reported by another study in which it was shown by immuno-histochemical examinations that NGAL expression was strongly up-regulated in well-differentiated oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) tissues and moderately to weakly up-regulated in moderately to poorly differentiated OSCC tissues as compared to normal mucosa and leukoplakia showing very weak expressions. Western blot analysis showed positive correlation of NGAL expression levels with cell morphology patterns and loss of E-cadherin[18]. So, NGAL levels may be raised as an effect or cause of tumor. NGAL may act as biomarker for diagnosis of HNSCC and for assessment of its severity.

Some limitations of our study include small sample size, lack of follow up and monitoring of the effect of treatment on NGAL outcome that will make part of our future project.

Our analysis demonstrates a potential role of NGAL as cancer biomarker which may be useful in monitoring the HNSCC progression. Many drugs which induce lipocalin 2 can be of therapeutic benefit in HNSCC to prevent metastasis and further spread.

The authors acknowledge the contribution of technical staff of Biochemistry Department.

Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), plays a significant role in generating innate immune response and safeguards against bacterial infections by sequestering iron. Recently, it has emerged as a biomarker for several benign and malignant diseases with its differential expression pattern.

As NGAL has anti-tumoral and anti-metastatic effect, it could be a new and effective biomarker for monitoring the progression of disease in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC).

NGAL was initially defined as a useful bacteriostatic agent actively against bacteria. Later on it was found that it acts as a biomarker of kidney injury but now a day it has emerged as a biomarker for several benign and malignant diseases. This study describes for the first time the increased levels of NGAL and its association with anti-metastatic effect in HNSCC.

The goal of treatment in HNSCC is mainly surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Biomarkers like NGAL having significant diagnostic and prognostic significance and with specific molecular target are demand of newer treatment modalities to increase the survival of patients.

In this study, the authors examined the levels of NGAL in patients with HNSCC in an Indian population. Overall, the methodology of the study is adequate, and the findings are clinically and scientifically relevant.

| 1. | Hardisson D. Molecular pathogenesis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2003;260:502-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Monisha J, Padmavathi G, Bordoloi D, Roy NK, Kunnumakkara AB. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL): A Promising Biomarker for Cancer Diagnosis and A Potential Target for Cancer Therapeutics. J Cell Sci Mol Biol. 2014;1:106. |

| 3. | Nilsen-Hamilton M, Liu Q, Ryon J, Bendickson L, Lepont P, Chang Q. Tissue involution and the acute phase response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;995:94-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nielsen BS, Borregaard N, Bundgaard JR, Timshel S, Sehested M, Kjeldsen L. Induction of NGAL synthesis in epithelial cells of human colorectal neoplasia and inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 1996;38:414-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bratt T. Lipocalins and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482:318-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lin CW, Yang WE, Lee WJ, Hua KT, Hsieh FK, Hsiao M, Chen CC, Chow JM, Chen MK, Yang SF. Lipocalin 2 prevents oral cancer metastasis through carbonic anhydrase IX inhibition and is associated with favourable prognosis. Carcinogenesis. 2016;37:712-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Furutani M, Arii S, Mizumoto M, Kato M, Imamura M. Identification of a neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin mRNA in human pancreatic cancers using a modified signal sequence trap method. Cancer Lett. 1998;122:209-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bartsch S, Tschesche H. Cloning and expression of human neutrophil lipocalin cDNA derived from bone marrow and ovarian cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 1995;357:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hall B, Nakashima H, Sun ZJ, Sato Y, Bian Y, Husain SR, Puri RK, Kulkarni AB. Targeting of interleukin-13 receptor α2 for treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma induced by conditional deletion of TGF-β and PTEN signaling. J Transl Med. 2013;11:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stejskal D, Karpísek M, Humenanska V, Hanulova Z, Stejskal P, Kusnierova P, Petzel M. Lipocalin-2: development, analytical characterization, and clinical testing of a new ELISA. Horm Metab Res. 2008;40:381-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Friedl A, Stoesz SP, Buckley P, Gould MN. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in normal and neoplastic human tissues. Cell type-specific pattern of expression. Histochem J. 1999;31:433-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Di Carlo A. The enigmatic role of lipocalin 2 in human cancer. The multifunctional protein neutrophilgelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) and its ambiguous role in human neoplasias. Prevent Res. 2012;P&R Public:12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Bouchet S, Bauvois B. Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL), Pro-Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (pro-MMP-9) and Their Complex Pro-MMP-9/NGAL in Leukaemias. Cancers (Basel). 2014;6:796-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chakraborty S, Kaur S, Guha S, Batra SK. The multifaceted roles of neutrophil gelatinase associated lipocalin (NGAL) in inflammation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:129-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tong Z, Kunnumakkara AB, Wang H, Matsuo Y, Diagaradjane P, Harikumar KB, Ramachandran V, Sung B, Chakraborty A, Bresalier RS. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a novel suppressor of invasion and angiogenesis in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6100-6108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hanai J, Mammoto T, Seth P, Mori K, Karumanchi SA, Barasch J, Sukhatme VP. Lipocalin 2 diminishes invasiveness and metastasis of Ras-transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13641-13647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: a promising biomarker for human acute kidney injury. Biomark Med. 2010;4:265-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 257] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shinriki S, Jono H, Ueda M, Obayashi K, Nakamura T, Ota K, Ota T, Sueyoshi T, Guo J, Hayashi M. Stromal expression of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin correlates with poor differentiation and adverse prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2014;64:356-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chen GS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ