Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.115245

Revised: November 11, 2025

Accepted: December 25, 2025

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 117 Days and 13.5 Hours

Despite widespread mammographic screening, a substantial proportion of breast cancers are still diagnosed as palpable lesions, frequently self-detected by the patient. Prior studies have investigated palpability as a prognostic factor, but few have incorporated contemporary staging systems or focused on clinically ho

To compare clinicopathological features and survival outcomes of palpable vs non-palpable breast cancers in a screened population.

We retrospectively analyzed 2110 women with clinically node-negative, localized breast cancer treated surgically between 2004 and 2024. Palpability at diagnosis was used to classify tumors as palpable (n = 1234) or non-palpable (n = 876). Endpoints included tumor size, grade, subtype, Ki-67 index, nodal status, overall survival, and breast cancer-specific survival. Statistical analyses included χ2 and t-tests and Kaplan-Meier estimates, with significance set at P < 0.05.

Palpable tumors were significantly larger (17.5 mm ± 8.6 vs 11.0 ± 6.7 mm, P < 0.001), more often high-grade (G3: 33% vs 16.3%, P < 0.001), and more frequently of luminal B or triple-negative subtype (37.1% vs 20.6%, P < 0.001). Ki-67 proliferation index was markedly higher in palpable tumors (24.7% ± 11.9% vs 15.1% ± 9.4%, P < 0.001). Sentinel lymph node positivity was increased (27.6% vs 16.7%, P < 0.001). While 10-year overall survival was similar (92% palpable vs 95% non-palpable, P = 0.56), breast cancer-specific survival showed a trend toward worse survival in palpable cases (96% vs 99%, P = 0.1).

Palpable tumors display faster growth kinetics and aggressive features, potentially shortening the preclinical window. Palpability may indicate biologically aggressive disease, warranting individualized management despite access to routine screening.

Core Tip: Despite widespread mammographic screening, many breast cancers still present as palpable masses. This large cohort study (n = 2110) reveals that palpable tumors exhibit aggressive biology-larger size (17.5 mm vs 11.0 mm, P < 0.001), higher grade (G3) (33% vs 16%), elevated Ki-67 (24.7% vs 15.1%), and more frequent luminal B/TN subtypes (P < 0.001). While 10-year survival remained excellent (> 90%) for both groups, palpability served as a clinical marker of rapid tumor growth, underscoring its utility in risk stratification. Findings highlight that even in screened populations, palpable presentation may signal biologically aggressive disease warranting tailored management.

- Citation: Improta L, Stanzani G, Vitale V, Yusef M, Tinghino S, Lombardi A. Palpable vs non-palpable breast cancers in screened populations: Clinicopathological features and prognostic implications. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 115245

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/115245.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.115245

Despite advances in screening and treatment, breast cancer is still one of the leading causes of cancer-related morbidity and mortality among women worldwide, with approximately 2.3 million new diagnoses and over 685000 deaths recorded in 2020 alone. Advanced age, a family history of breast cancer, and specific genetic mutations are among the most well-established risk factors. Early detection has proven crucial in improving survival rates and reducing the need for extensive surgical procedures. Over the years, advancements in imaging techniques and the widespread implementation of population-based screening programs have facilitated the identification of breast lesions at increasingly earlier stages, often before they become palpable or clinically evident[1-4]. However, the presence of a palpable breast mass remains a significant clinical finding, particularly in settings where screening programs are not widely available or accessible. Recent studies indicate that the proportion of breast cancers diagnosed following the detection of a palpable mass varies based on geographic location, access to screening, and public awareness. In regions with limited economic and healthcare resources, where screening is not systematically available or universally accessible, up to 50%-70% of breast cancers are diagnosed only once the lesion has become palpable. Conversely, in countries with well-established screening programs – such as those in Europe and North America – the majority of breast cancers are detected through screening mammo

Several studies have explored palpability as a potential prognostic indicator. Available data highlight that between 40% and 60% of all breast cancers may be considered palpable at the time of diagnosis, even though the appearance of a palpable mass was not the initial presenting sign, and the diagnosis was made following a screening mammography. In these cases, the palpable lesions have also been associated with signs of greater biological aggressiveness, more advanced stage at diagnosis, and a poorer prognosis[14,15].

Most of the existing studies, however, have primarily focused on mammographic features, analyzed heterogeneous populations or cohorts with limited or partial access to screening programs, or relied on predominantly retrospective series. Additionally, few studies have critically integrated prognostic staging information in accordance with the updated eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system, introduced in 2017, and none have specifically focused on patients with localized breast cancer and clinically negative lymph nodes[16].

This study aims to compare the clinical, histological, and prognostic characteristics of palpable vs non-palpable localized breast cancers with clinically negative lymph nodes at diagnosis in a high-volume referral center within a high-income country with a well-established and effective screening program. By analyzing a large prospectively collected cohort over a 20-year period, we seek to identify significant differences between the two groups and assess the impact of tumor palpability on prognosis, taking into account tumor characteristics, potential confounders, and prognostic staging within the context of an effective screening program.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted by analyzing clinical and histopathological data from a prospectively collected series of 3079 consecutive patients diagnosed with primary (non-recurrent, non-metastatic) breast cancer and surgically treated at the Breast Unit of a high-volume university hospital between October 2004 and June 2024. Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) Age > 18 years; (2) Female sex; (3) First diagnosis of invasive breast cancer (regardless of receptor status or molecular profile); (4) Eligibility for upfront breast-conserving surgery with curative intent; and (5) Signed informed consent for data use in research. Patients were excluded if they had confirmed systemic or nodal metastases as per current guideline-approved diagnostic methods, had been enrolled in experimental trials or treated with investigational drugs in the previous year, or had a diagnosis of carcinoma in situ. All patients were considered for surgery following a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion. All patients underwent breast-conserving surgery with sentinel lymph node biopsy. Non-palpable lesions were preoperatively localized and marked under ultrasound or stereotactic guidance by experienced, dedicated radiologists. Histopathological diagnosis, classification, and grading were performed on preoperative biopsy and confirmed on the final histopathological examination of the surgical specimen by expert pathologists at a high-volume pathology department, in accordance with the latest guidelines. Ki-67 immunohistochemical staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections using the MIB-1 monoclonal antibody (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Ki-67 Labeling index was assessed by evaluating at least 500 invasive tumor cells in areas of highest nuclear labeling (hot spots) and expressed as the percentage of positively stained nuclei. All Ki-67 assessments were performed by experienced pathologists according to the International Ki-67 in Breast Cancer Working Group recommendations, ensuring standardized and reproducible evaluation throughout the study period. Molecular classification, based on immunohistochemical surrogates for estrogen and progesterone receptor, HER2, and Ki-67 status, was performed in accordance with the St. Gallen Expert Consensus and European Society for Medical Oncology guidelines. Consequently, the Ki-67 cut-off for distinguishing between luminal A and luminal B subtypes was set at 20%, and cases with equivocal HER2 immunohistochemistry results were further assessed by means of fluorescence in-situ hybridization[16-18]. All patients received adjuvant therapies according to the most up-to-date guideline-based protocols available at the time of treatment following a multidisciplinary tumor board discussion. All patients provided written informed consent for the use of their anonymized data for scientific purposes, and the study was approved by the local Institutional Review Boards and Ethics Committees, in compliance with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

Palpable lesions were defined as those clinically detectable by physical examination during the initial breast specialist consultation, performed by senior breast surgeons with at least 10 years of dedicated breast surgery experience. Physical examination was conducted systematically in both supine and sitting positions, with palpation of all four quadrants and the retroareolar region. To minimize inter-operator variability, all findings were documented according to a standardized clinical assessment protocol, including lesion location, size estimation, consistency, and mobility. In cases of uncertainty, a second senior surgeon performed an independent examination, and consensus was reached through discussion. This standardized approach ensured consistent classification of tumor palpability throughout the study period. Based on clinical presentation, patients were categorized into two subgroups: Palpable and non-palpable lesions, which repre

The prospective database was constructed using Microsoft® Access, and selected records were transferred to Microsoft® Excel. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM-SPSS® version 27. Categorical and continuous variables were compared using the χ2 test, while differences between means were assessed with Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, while P < 0.01 was considered highly significant. OS and BCRS were estimated and compared across subgroups using the Kaplan-Meier method.

From the initial cohort of 3079 non-recurrent, non-metastatic, consecutively treated patients, 969 were excluded based on the following criteria: (1) 501 patients (51.7%) required mastectomy rather than breast-conserving surgery; (2) 341 patients (35.2%) were diagnosed with carcinoma in situ; and (3) 127 patients (13.1%) underwent chemotherapy among standard protocols or experimental trials during the previous year. A total of 2110 patients diagnosed with localized primary breast cancer and clinically negative lymph nodes at preoperative staging, who underwent upfront breast-conserving surgery, constituted the study cohort. The mean patient age was 59.5 years. Overall, 1234 patients (58.5%) presented with a palpable lesion at diagnosis, whereas 876 patients (41.5%) had non-palpable lesions at onset. The clinicopathologic characteristics of the two subgroups are summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | Entire cohort | Palpability | P value | |||||

| No | Yes | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Patients | 2110 | 100 | 876 | 41.5 | 1234 | 58.5 | NS | |

| Age | ≤ 50 | 604 | 28.6 | 249 | 28.4 | 355 | 28.8 | NS |

| > 50 | 1506 | 71.4 | 627 | 71.6 | 879 | 71.2 | ||

| Tumor size (mm) | 14.8 (8.5) | 11 (6.7) | 17.5 (8.6) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Surgical technique | Oncoplasty | 1314 | 62.3 | 646 | 73.7 | 668 | 54.1 | < 0.001 |

| Traditional | 796 | 37.7 | 230 | 26.3 | 566 | 45.9 | ||

| Histotype | Infiltrating ductal carcinoma | 1785 | 84.6 | 758 | 86.5 | 1027 | 83.3 | NS |

| Infiltrating lobular carcinoma | 236 | 11.2 | 85 | 9.7 | 151 | 12.2 | ||

| Other | 89 | 4.2 | 33 | 3.8 | 56 | 4.5 | ||

| Grading | 1 | 637 | 30.2 | 338 | 38.6 | 299 | 24.2 | < 0.001 |

| 2 | 915 | 43.3 | 388 | 44.3 | 525 | 42.5 | ||

| 3 | 550 | 26.1 | 143 | 16.3 | 407 | 33 | ||

| Not assessable | 9 | 0.4 | 6 | 0.7 | 3 | 0.2 | ||

| Multifocality | No | 1841 | 87.3 | 744 | 84.9 | 1097 | 88.9 | 0.007 |

| Yes | 269 | 12.7 | 132 | 15.1 | 137 | 11.1 | ||

| Limphovascular invasion | No | 1722 | 81.6 | 725 | 82.8 | 997 | 80.8 | NS |

| Yes | 388 | 18.4 | 151 | 17.2 | 237 | 19.2 | ||

| N | N+ | 486 | 23 | 146 | 16.7 | 340 | 27.6 | < 0.001 |

| N0 | 1621 | 76.9 | 729 | 83.2 | 892 | 72.3 | ||

| Nx | 3 | 0.1 | 1 | 0.1 | 2 | 0.2 | ||

| Subtype1 | HER2+ | 61 | 2.9 | 24 | 2.7 | 37 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| HER2 HRP+ | 134 | 6.4 | 56 | 6.4 | 78 | 6.3 | ||

| Luminal A | 1269 | 60.1 | 611 | 69.7 | 658 | 53.3 | ||

| Luminal B | 492 | 23.3 | 128 | 15.8 | 354 | 28.7 | ||

| Triple negative | 146 | 6.9 | 42 | 4.8 | 104 | 8.4 | ||

| Ki67 | 19.8 (15.6) | 15.9 (13.8) | 22.5 (16.2) | < 0.001 | ||||

| R1 rate | 194 | 9.2 | 96 | 11 | 98 | 7.9 | < 0.005 | |

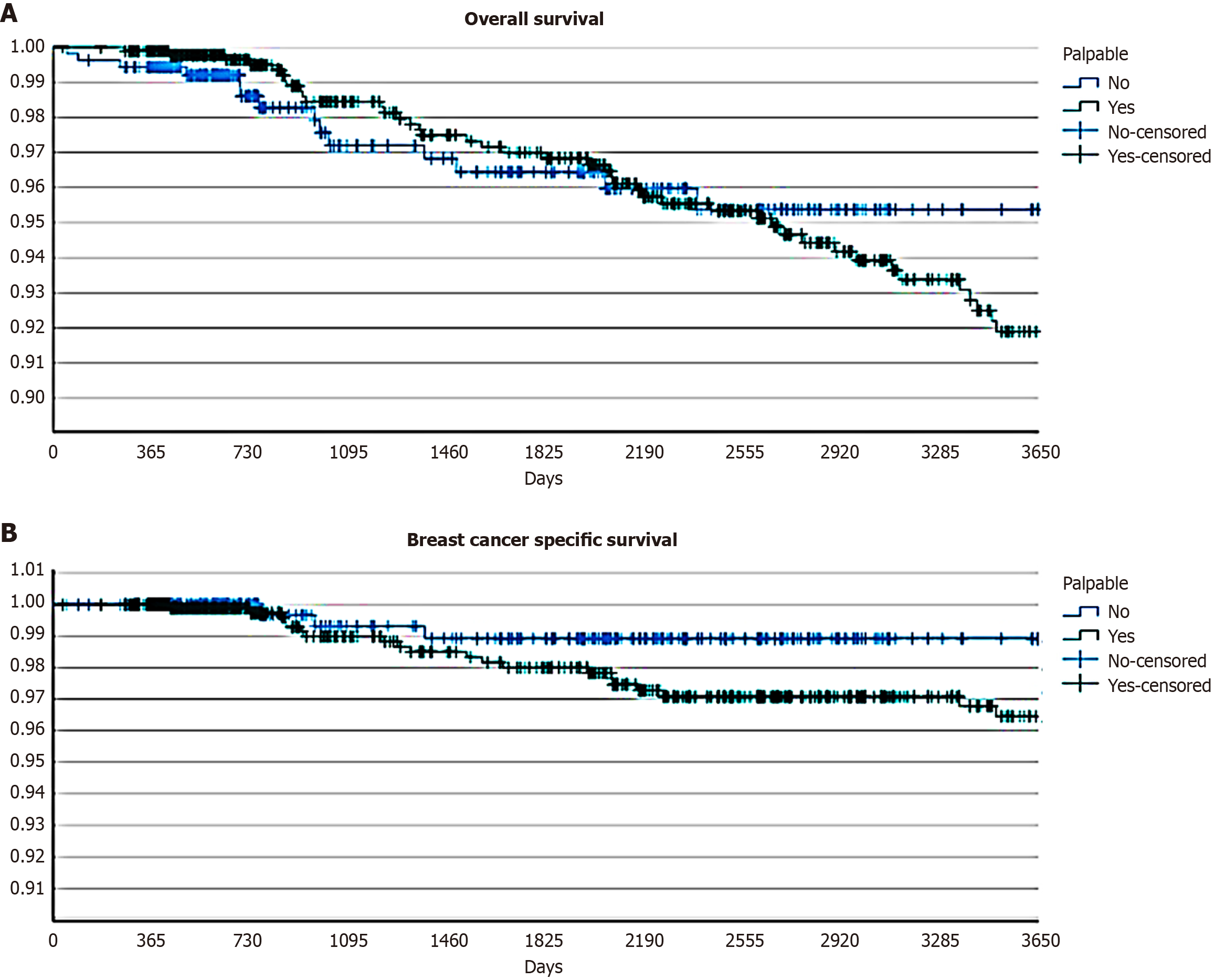

The study achieved a 68.4% follow-up adherence rate, comprising 1444 patients. Baseline characteristics of the 666 patients lost to follow-up (31.6%) were comparable to those with complete follow-up data. Among lost-to-follow-up patients, 58.1% had palpable lesions vs 58.5% in the followed cohort (P = 0.84). No significant differences were observed in terms of age distribution (mean age: 59.3 years vs 59.6 years, P = 0.68), tumor size (mean: 14.9 mm vs 14.8 mm, P = 0.89), histological grade distribution (G3: 25.8% vs 26.1%, P = 0.88), molecular subtype distribution (P = 0.72), or Ki-67 (mean: 19.5% vs 19.8%, P = 0.82). The similar distribution of both palpability status and other prognostic factors between followed and lost-to-follow-up patients suggests that attrition did not introduce significant selection bias in survival analysis. After a median follow-up of 5.7 years (interquartile range: 1.8-10.4 years), 30 patients (2.1%) had died from breast cancer, while 42 (2.9%) had died from other causes. At the time of analysis, 120 patients (8.3%) were alive with disease: (1) 60 with local recurrence; (2) 24 with metachronous contralateral breast cancer; (3) 12 with axillary nodal relapse; and (4) 33 with distant metastasis. The 10-year OS rate exceeded 90% across the entire cohort (92.5%). Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the two subgroups (95% non-palpable lesions vs 92% palpable lesions, P = 0.56), a trend toward earlier mortality was noted in patients with palpable lesions (Figure 1A). To validate the reliability of 10-year survival estimates derived from Kaplan-Meier analysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to the 687 patients with at least 10 years of documented follow-up (47.6% of patients with available follow-up data). Baseline characteristics of this long-term follow-up subgroup were comparable to those of the entire cohort, with similar distributions of palpability status (57.9% vs 58.5% in total cohort, P = 0.78), age (P = 0.71), tumor size (P = 0.63), grade (P = 0.58), and molecular subtypes (P = 0.69), confirming its representativeness. Among patients with complete 10-year follow-up, the observed 10-year OS was 91.7% (93.8% for non-palpable vs 90.5% for palpable lesions, P = 0.52), closely matching the Kaplan-Meier estimates for the entire cohort. These findings support the validity of our survival projections and confirm that the Kaplan-Meier method appropriately accounted for censoring in our dataset.

Similarly, for BCSS, no statistically significant difference was detected at 10 years (overall BCSS 97%; 99% non-palpable lesions vs 96% palpable lesions, P = 0.1). Even in the absence of statistical significance, a trend toward lower survival was observed in patients presenting with palpable lesions at diagnosis (Figure 1B).

The study achieved a 68.4% follow-up adherence rate, comprising 1444 patients. Baseline characteristics of the 666 patients lost to follow-up (31.6%) were comparable to those with complete follow-up data. Among lost-to-follow-up patients, 58.1% had palpable lesions vs 58.5% in the followed cohort (P = 0.84). No significant differences were observed in terms of age distribution (mean age: 59.3 years vs 59.6 years, P = 0.68), tumor size (mean: 14.9 mm vs 14.8 mm, P = 0.89), histological grade distribution (G3: 25.8% vs 26.1%, P = 0.88), molecular subtype distribution (P = 0.72), or Ki-67 (mean: 19.5% vs 19.8%, P = 0.82). The similar distribution of both palpability status and other prognostic factors between followed and lost-to-follow-up patients suggests that attrition did not introduce significant selection bias in survival analysis. After a median follow-up of 5.7 years (interquartile range 1.8-10.4 years), 30 patients (2.1%) had died from breast cancer, while 42 (2.9%) had died from other causes. At the time of analysis, 120 patients (8.3%) were alive with disease: (1) 60 with local recurrence; (2) 24 with metachronous contralateral breast cancer; (3) 12 with axillary nodal relapse; and (4) 33 with distant metastasis. The 10-year OS rate exceeded 90% across the entire cohort (92.5%). Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the two subgroups (95% non-palpable lesions vs 92% palpable lesions, P = 0.56), a trend toward earlier mortality was noted in patients with palpable lesions (Figure 1A). To validate the reliability of 10-year survival estimates derived from Kaplan-Meier analysis, we performed a sensitivity analysis restricted to the 687 patients with at least 10 years of documented follow-up (47.6% of patients with available follow-up data). Baseline characteristics of this long-term follow-up subgroup were comparable to those of the entire cohort, with similar distributions of palpability status (57.9% vs 58.5% in total cohort, P = 0.78), age (P = 0.71), tumor size (P = 0.63), grade (P = 0.58), and molecular subtypes (P = 0.69), confirming its representativeness. Among patients with complete 10-year follow-up, the observed 10-year OS was 91.7% (93.8% for non-palpable vs 90.5% for palpable lesions, P = 0.52), closely matching the Kaplan-Meier estimates for the entire cohort. These findings support the validity of our survival projections and confirm that the Kaplan-Meier method appropriately accounted for censoring in our dataset.

Similarly, for BCSS, no statistically significant difference was detected at 10 years (overall BCSS 97%; 99% non-palpable lesions vs 96% palpable lesions, P = 0.1). Even in the absence of statistical significance, a trend toward lower survival was observed in patients presenting with palpable lesions at diagnosis (Figure 1B).

This study sought to investigate the clinical, histopathological, and prognostic differences between palpable and non-palpable breast tumors in a large, prospectively collected cohort of patients with early-stage, node-negative disease treated in a high-volume tertiary referral center within a high-income country with an established national screening program.

Our findings indicate that palpable lesions accounted for 58.5% of all cases, a proportion situated at the upper end of the range reported in the literature[14,15]. Such a discrepancy may be partially explained by multiple interconnected factors. Our center serves as a referral center in a large metropolitan area, and this could have influenced the composition of the population of our cohort. As our center does not perform population-based screening, a referral bias likely exists: Smaller screen-detected lesions may be more frequently managed at peripheral or spoke centers and therefore be underrepresented in our series, while more clinically evident tumors were directly referred to our tertiary institution for surgical management, and also interval cancers – characterized by an intrinsic more aggressive behavior – may be overrepresented in surgical referral centers compared to population-based screening registries. Moreover, the me

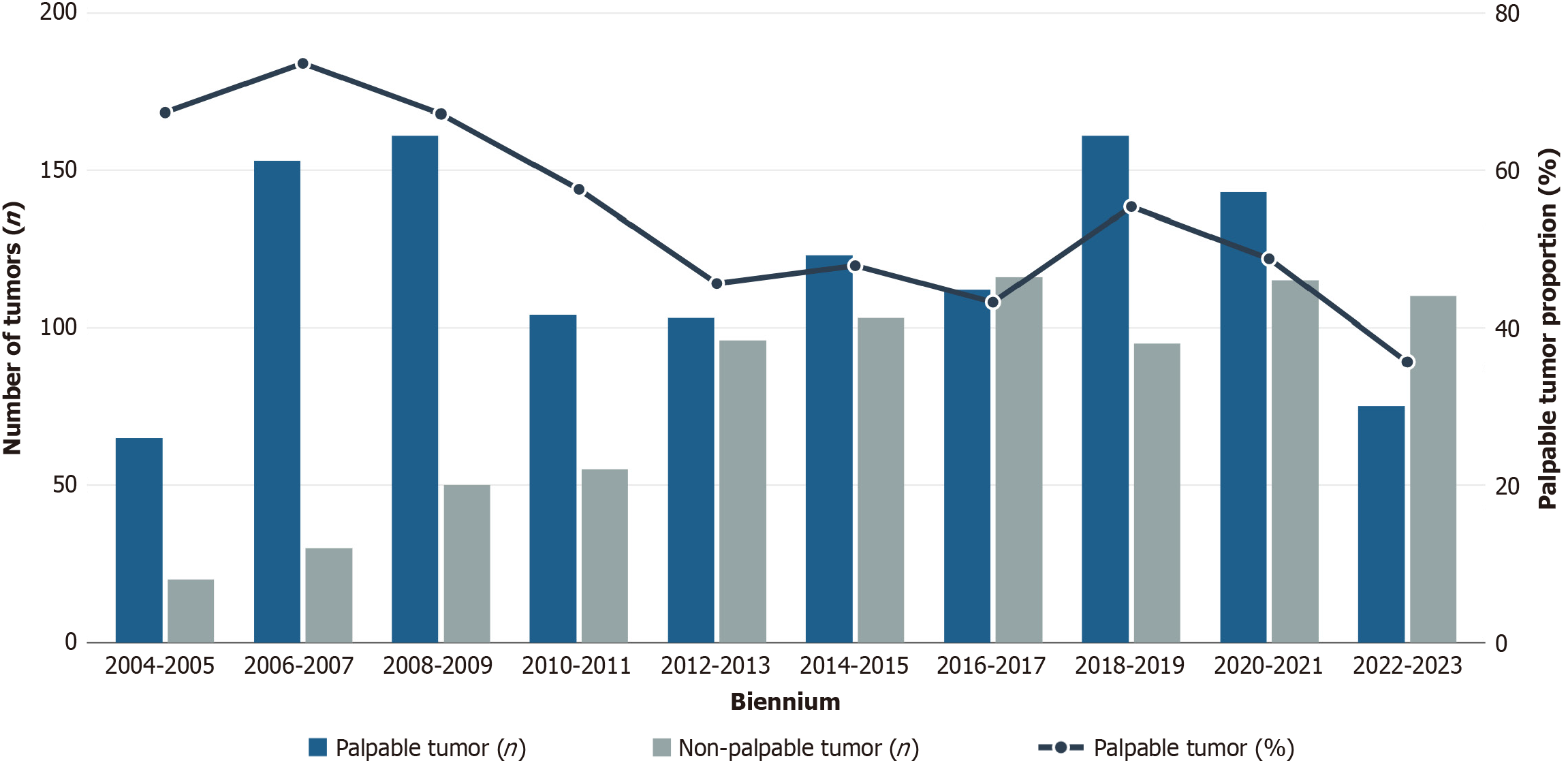

As discussed above, the long study period spanning over two decades (2004-2024) during which screening technologies and participation rates evolved considerably, may have contributed to the actual mean rate of palpability, that may be influenced by an overrepresentation of palpable lesion in the first years of the study. Indeed, the proportion of palpable tumors was not constant over time. An analysis of temporal trends (Figure 2) revealed a gradual but significant reduction in the incidence of palpable presentations, which over the past two decades have been overtaken by non-palpable cases. This temporal shift likely reflects the progressive improvement in screening technologies, particularly digital mammography and tomosynthesis, as well as heightened public awareness and adherence to screening reco

A temporary reversal in the prevailing trend was observed during the years encompassing the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, with palpable tumors once again representing the majority of diagnoses. This shift, which persisted into the year immediately following the pandemic, is likely attributable to a transient reduction in access to screening programs and a diminished public focus on preventive care. In the subsequent biennium, the proportion of non-palpable tumors at diagnosis regained predominance, realigning with the pre-pandemic trend.

These multifactorial influences may collectively explain the discrepancy with population-based screening data and underscore the importance of contextualizing our findings within the specific referral patterns and patient population characteristics of our tertiary surgical center, and the diagnostic and cultural changing occurred during the study period.

The age distribution in our cohort is consistent with epidemiological data reported in the literature, with 71.4% of patients over 50 years of age and 28.6% under 50. These proportions were mirrored in both the palpable and non-palpable subgroups, suggesting that age alone does not significantly influence the clinical presentation of breast cancer at diagnosis, in line with previously published studies[15].

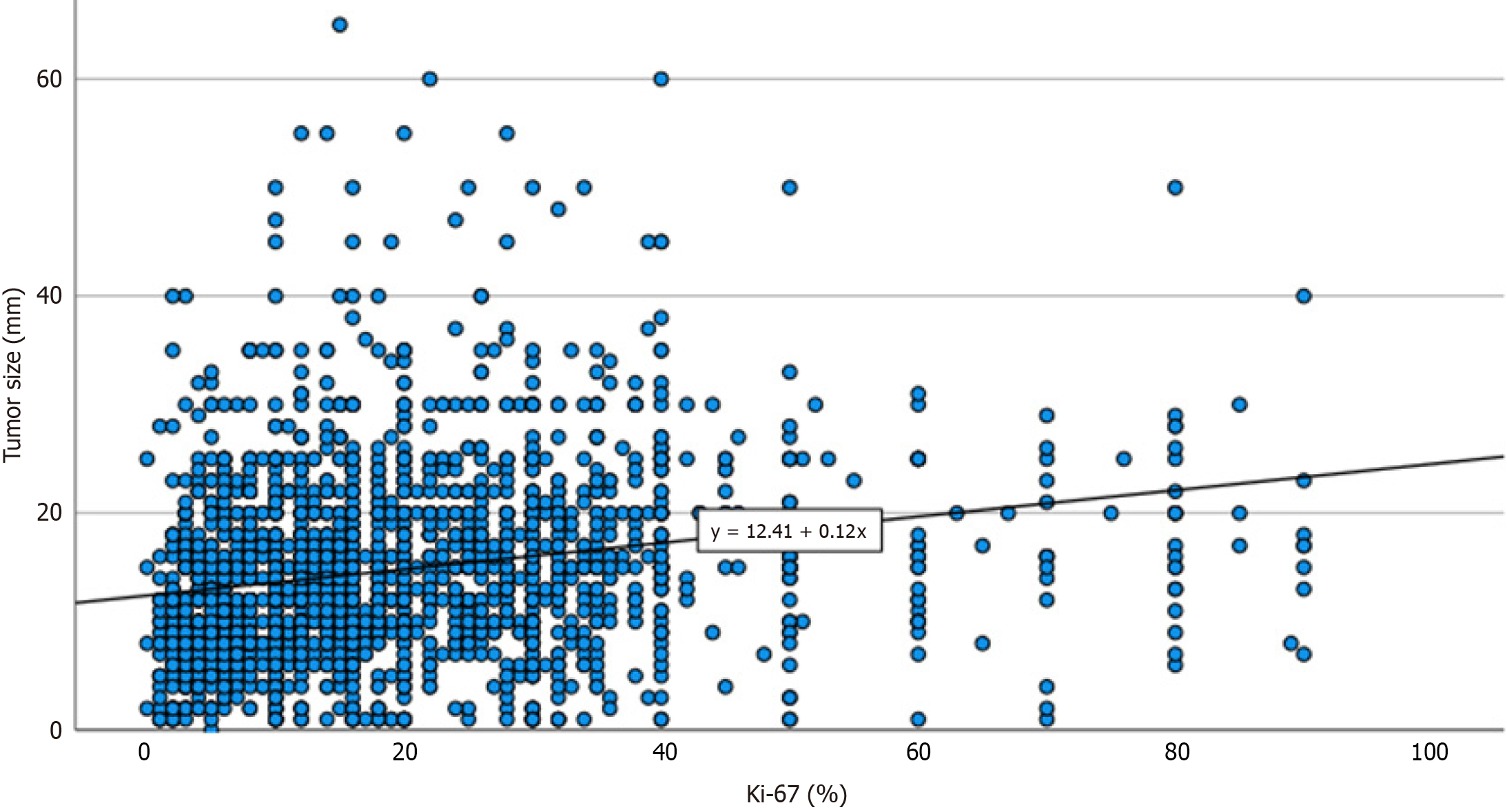

Histopathological analysis revealed that palpable tumors were significantly larger at diagnosis, were more frequently of higher histological grade, and had a higher mean Ki-67 proliferative index. As evidenced in Figure 3, the correlation between tumor size and Ki-67 suggests that palpability may reflect a more rapid growth dynamic, which in turn shortens the subclinical latency phase and increases the likelihood of a tumor becoming clinically evident before being detected through routine screening. Furthermore, palpable tumors were more commonly associated with aggressive molecular subtypes, including luminal B and triple-negative breast cancers, and had a higher incidence of sentinel lymph node positivity at diagnosis. Although tumor palpability in itself is not an independent biological determinant of prognosis, it appears to serve as a clinical proxy for a constellation of unfavorable prognostic factors, including higher T-stage, elevated proliferative activity, and biologically aggressive subtypes. This aggregate prognostic value renders palpability a potentially useful clinical indicator, readily available during initial clinical assessment, which could help stratify risk and guide therapeutic decision-making. In this context, the simple clinical observation of palpability might prompt a more cautious evaluation and intensified follow-up strategy. This approach may be particularly valuable in resource-limited contexts: In clinical settings where molecular or histopathological data are not immediately available, the presence of a palpable lesion may justify early multidisciplinary discussion or expedited imaging and treatment decisions.

Despite the more frequent association of palpable tumors with adverse pathological features, long-term survival outcomes in our cohort did not significantly differ between the two groups. The 10-year OS and BCSS rates exceeded 90% across the cohort, with only a non-significant trend towards worse outcomes among patients with palpable tumors. The absence of statistically significant differences in BCSS between palpable and non-palpable tumors (96% vs 99%, P = 0.1) warrants careful interpretation. While a trend toward lower survival in palpable cases was observed, our study may have been underpowered to detect modest differences in breast cancer-specific mortality, particularly given the excellent overall prognosis of early-stage, node-negative disease and the relatively low event rate (2.1% breast cancer deaths) in our cohort. A post-hoc power analysis indicated that detecting a 3% absolute difference in BCSS with 80% power and α = 0.05 would require approximately 3500 patients per group – substantially larger than our cohort. Nevertheless, the observed trend is clinically relevant and consistent with the more aggressive biological features documented in palpable tumors.

Moreover, our finding likely reflects the efficacy of modern multimodal treatment protocols – including chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, and radiotherapy – in mitigating the adverse impact of aggressive tumor biology. It also underscores the utility of the American Joint Committee on Cancer prognostic staging system in integrating clinical, pathological, and biomolecular information to guide therapeutic strategies and predict long-term outcomes. Larger multi-institutional studies with longer follow-up and adequate statistical power may be needed to definitively establish the prognostic significance of palpability for breast cancer-specific outcomes in contemporary cohorts treated with modern multimodal therapy.

This study may acknowledge several limitations. As previously discussed, its single-center design may introduce selection bias, potentially overestimating the proportion of palpable tumors. On the other hand, the specific inclusion and exclusion criteria adopted (primary non-metastatic and non-recurrent, clinically node-negative patient candidate to upfront conservative surgery) may have selected patients with smaller tumors, limiting our possibility to generalize our results to all breast cancer patients. Additionally, even in the context of a tertiary referral center, the absence of external radiology and pathology review could affect data homogeneity. Another limitation of this study is the lack of detailed, systematically recorded data on adjuvant treatment administration. While all patients received guideline-concordant multimodal therapy based on tumor characteristics and multidisciplinary tumor board recommendations, our database does not capture patient-level information on specific chemotherapy regimens, endocrine therapy duration, or ra

In a large cohort of patients with early-stage breast cancer and clinically negative axillary nodes, tumor palpability at diagnosis was associated with larger tumor size, higher histological grade, increased Ki-67 proliferation index, and a greater prevalence of aggressive molecular subtypes. These findings suggest that palpability represents a composite clinical indicator of more biologically aggressive disease, rather than being an independent prognostic factor, potentially shortening the preclinical window.

Nevertheless, long-term survival outcomes were excellent across both subgroups, and no statistically significant differences were observed in OS or BCSS, suggesting that the adverse biological features associated with palpable tumors may be effectively counterbalanced by appropriate treatment strategies. These results further support the prognostic validity of integrated staging systems and highlight the importance of maintaining access to multimodal therapy, even in patients presenting with more clinically evident disease.

These findings reinforce the importance of considering palpability as a clinically relevant, readily assessable parameter that may help inform initial risk stratification and management, particularly in settings where access to complete dia

| 1. | Arnold M, Morgan E, Rumgay H, Mafra A, Singh D, Laversanne M, Vignat J, Gralow JR, Cardoso F, Siesling S, Soerjomataram I. Current and future burden of breast cancer: Global statistics for 2020 and 2040. Breast. 2022;66:15-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 600] [Cited by in RCA: 1828] [Article Influence: 457.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68713] [Article Influence: 13742.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 3. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127:3029-3030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 924] [Cited by in RCA: 1479] [Article Influence: 295.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Toffolutti F, Guzzinati S, De Paoli A, Francisci S, De Angelis R, Crocetti E, Botta L, Rossi S, Mallone S, Zorzi M, Manneschi G, Bidoli E, Ravaioli A, Cuccaro F, Migliore E, Puppo A, Ferrante M, Gasparotti C, Gambino M, Carrozzi G, Stracci F, Michiara M, Cavallo R, Mazzucco W, Fusco M, Ballotari P, Sampietro G, Ferretti S, Mangone L, Rizzello RV, Mian M, Cascone G, Boschetti L, Galasso R, Piras D, Pesce MT, Bella F, Seghini P, Fanetti AC, Pinna P, Serraino D, Dal Maso L; AIRTUM Working Group. Complete prevalence and indicators of cancer cure: enhanced methods and validation in Italian population-based cancer registries. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1168325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Duffy SW, Vulkan D, Cuckle H, Parmar D, Sheikh S, Smith RA, Evans A, Blyuss O, Johns L, Ellis IO, Myles J, Sasieni PD, Moss SM. Effect of mammographic screening from age 40 years on breast cancer mortality (UK Age trial): final results of a randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1165-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Newman LA. Breast cancer screening in low and middle-income countries. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;83:15-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schueler KM, Chu PW, Smith-Bindman R. Factors associated with mammography utilization: a systematic quantitative review of the literature. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17:1477-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lehman CD, Wellman RD, Buist DS, Kerlikowske K, Tosteson AN, Miglioretti DL; Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium. Diagnostic Accuracy of Digital Screening Mammography With and Without Computer-Aided Detection. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1828-1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Houssami N, Abraham LA, Miglioretti DL, Sickles EA, Kerlikowske K, Buist DS, Geller BM, Muss HB, Irwig L. Accuracy and outcomes of screening mammography in women with a personal history of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA. 2011;305:790-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hofvind S, Sørum R, Thoresen S. Incidence and tumor characteristics of breast cancer diagnosed before and after implementation of a population-based screening-program. Acta Oncol. 2008;47:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bianchini G, Balko JM, Mayer IA, Sanders ME, Gianni L. Triple-negative breast cancer: challenges and opportunities of a heterogeneous disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13:674-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 2127] [Article Influence: 212.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Duffy SW, Tabár L, Chen HH, Holmqvist M, Yen MF, Abdsalah S, Epstein B, Frodis E, Ljungberg E, Hedborg-Melander C, Sundbom A, Tholin M, Wiege M, Akerlund A, Wu HM, Tung TS, Chiu YH, Chiu CP, Huang CC, Smith RA, Rosén M, Stenbeck M, Holmberg L. The impact of organized mammography service screening on breast carcinoma mortality in seven Swedish counties. Cancer. 2002;95:458-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ambinder EB, Lee E, Nguyen DL, Gong AJ, Haken OJ, Visvanathan K. Interval Breast Cancers Versus Screen Detected Breast Cancers: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Acad Radiol. 2023;30 Suppl 2:S154-S160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Skinner KA, Silberman H, Sposto R, Silverstein MJ. Palpable breast cancers are inherently different from nonpalpable breast cancers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:705-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim D, Lee SJ, Ko BK, Lee H, Yoon JH, Lee SW, Jeon YW, Kim BK, Lee J, Sun WY. The Clinicopathological Characteristics of Palpable and Non-palpable Breast Cancer. J Breast Dis. 2020;8:92-99. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | American Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Cham: Springer, 2002. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Goldhirsch A, Winer EP, Coates AS, Gelber RD, Piccart-Gebhart M, Thürlimann B, Senn HJ; Panel members. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2206-2223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2486] [Cited by in RCA: 2798] [Article Influence: 215.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cardoso F, Kyriakides S, Ohno S, Penault-Llorca F, Poortmans P, Rubio IT, Zackrisson S, Senkus E; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Early breast cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up†. Ann Oncol. 2019;30:1194-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 635] [Cited by in RCA: 1464] [Article Influence: 244.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/