Published online Feb 24, 2026. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.114298

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: January 6, 2026

Published online: February 24, 2026

Processing time: 143 Days and 18.3 Hours

Tumor dormancy is a fundamental phenomenon in cancer biology, characterized by malignant cells that remain viable but non-proliferative, thereby frequently evading detection and treatment. This review examines the intricate role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in regulating tumor cell dormancy. The TME encompasses a diverse array of components, including immune cells, extracellular matrix proteins, and soluble factors, all of which contribute to a dynamic interplay that influences tumor cell behavior. Key mechanisms involved in the maintenance of dormancy include immune surveillance, where immune cells can either sup

Core Tip: This article explores the critical role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in regulating tumor dormancy, a state in which malignant cells remain viable but non-proliferative, contributing to metastasis and recurrence. We highlight the dynamic interactions within the TME, including immune cell modulation, extracellular matrix components, and metabolic factors, that maintain dormancy. The article discusses promising therapeutic strategies targeting the TME to either awaken dormant cells for treatment or maintain their quiescence, aiming to improve cancer treatment outcomes and prevent recurrence.

- Citation: Qian YR, Liu P, Xu H, Lv Y, Zhang XF, Xiang JX. Microenvironment plays a critical role in modulating tumor cell dormancy: Current perspectives and potential treatment options. World J Clin Oncol 2026; 17(2): 114298

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v17/i2/114298.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v17.i2.114298

Recurrence and metastasis are major contributors to cancer-related mortality. Even with curative-intent treatments or sequential adjuvant therapies, some malignant cells inevitably spread to distant sites and organs over extended periods. Before the gross appearance of tumor metastasis and recurrence, it is often difficult to detect the existence of tumor cells in patients, as they may exist in a dormant, non-proliferating phase[1]. When tumor cells enter dormancy due to growth pressures in the new environment or a lack of necessary growth factors, they can re-enter a state of proliferation when conditions are favorable. This phenomenon is known as tumor dormancy. Cellular dormancy refers to a state where individual tumor cells remain viable but non-proliferative, often evading detection and therapeutic targeting. In contrast, population dormancy involves the entire tumor mass or a subpopulation of tumor cells, which collectively enter a quiescent state, often due to external microenvironmental cues such as immune surveillance or nutrient deprivation[2]. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is pivotal in maintaining this state. The TME refers to the complex network of surrounding cells, extracellular matrix (ECM), blood vessels, immune cells, and various soluble factors that interact with tumor cells. This environment plays a crucial role in regulating tumor progression, dormancy, metastasis, and response to therapy. Understanding the TME is essential, as its composition and the dynamic interactions within it influence cancer cell behavior, including their ability to enter a dormant state and evade therapeutic interventions.

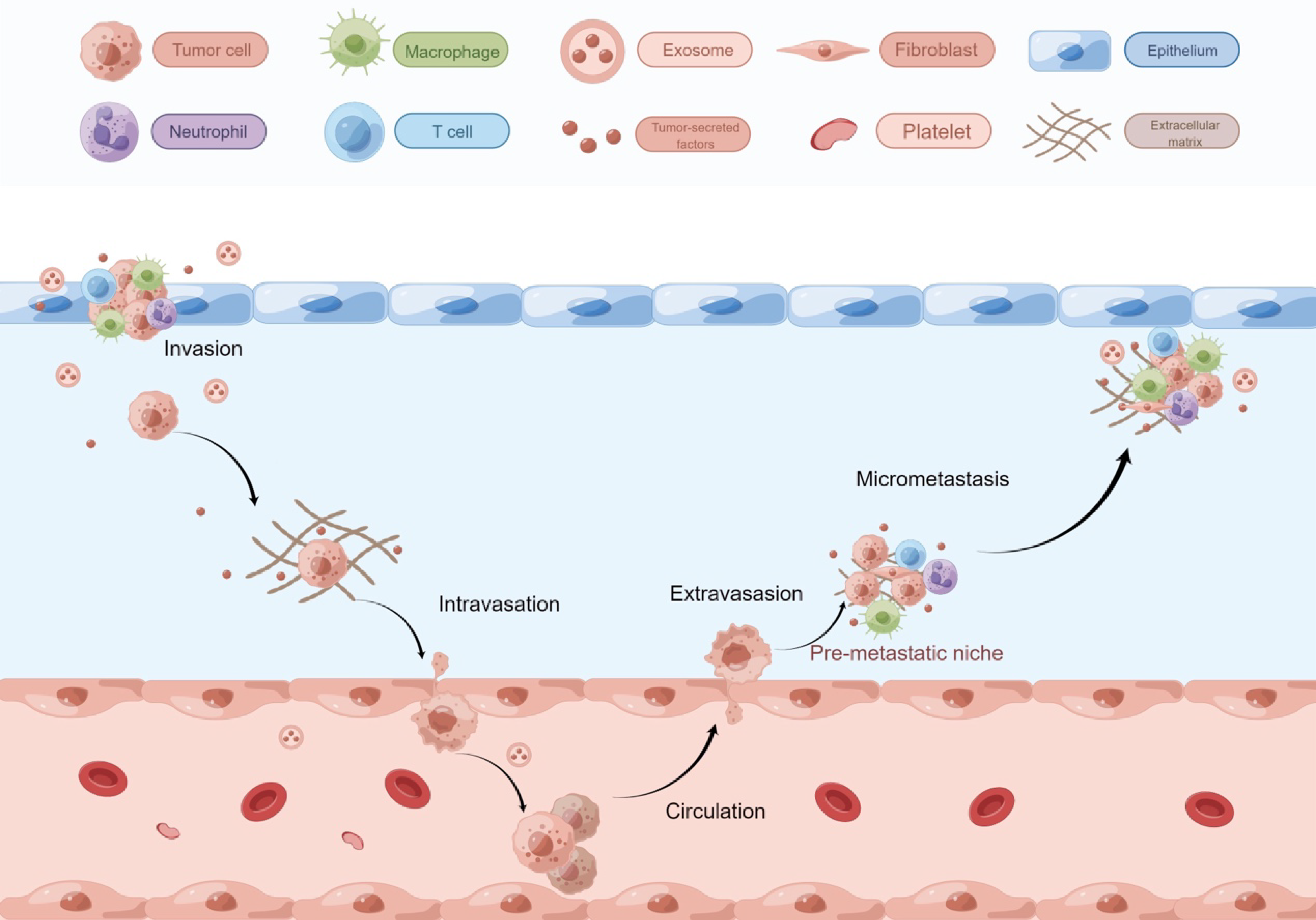

Traditionally, tumor cell dissemination was viewed as a late-stage metastatic event, but recent studies show it can occur early, with varying rates across organs[3,4]. Circulating tumor cells enter the bloodstream, while disseminated tumor cells (DTCs)[5] colonize distant tissues. Early dissemination can happen before the primary tumor is palpable[6,7].

Dormancy is modulated by TME factors, including immune cells, ECM, and signaling molecules. CD8+ T cells, natural killer (NK) cells, metabolic constraints, and limited vascularization help maintain dormancy. This review focuses on the dynamic interactions between tumor cells and the TME, which contribute to the maintenance of dormancy. We will focus on understanding how various TME components, such as immune cells, ECM proteins, and soluble factors, modulate dormancy, and how these insights can lead to novel therapeutic strategies aimed at reactivating dormant cells or pre

Cancer is a systemic disease rather than a localized condition[8]. The term “cancer” encompasses both tumor cells and the surrounding TME, akin to the relationship between a seed and its soil[9]. The TME is often described using the “seed and soil” theory, which posits that the tumor cell (the seed) is influenced by and interacts with the surrounding microenvironment (the soil). This theory emphasizes that the soil, or the TME, can either support or hinder the growth of metastatic cells depending on its characteristics. A conducive TME can provide the necessary signals for tumor cells to survive, pro

Tumor dormancy acts as an adaptive mechanism that enables malignant cells to endure stressful conditions within the TME. Dormancy is classified into two types: Population dormancy and cell dormancy[11]. Population dormancy, which includes angiogenic and immune dormancy, involves a tumor mass lacking vascular-derived nutrients due to vascular or angiogenic regulation. Immunosurveillance during this phase maintains a balance between proliferation and apoptosis, stabilizing tumor size[1]. In contrast, cell dormancy describes individual tumor cells in a quiescent, reversible G0/G1 cell cycle arrest[12].

Upon migrating to distant sites and entering dormancy, tumor cells rely on support and regulatory cues from the TME. The concept of “microenvironmental control”[13] highlights how non-immune cells, host-derived soluble factors, and “part-time” innate molecules suppress tumor proliferation or eliminate cancer cells.

Niches are specialized TME that enable communication through cellular and ECM interactions, as well as intercellular signaling. Before tumor cells spread, they build a prototype “house” called the pre-metastatic niche (PMN)[14-16], supported by soluble factors from the primary tumor[8]. Myeloid cells, endothelial cells, and stromal cells secrete chemokines, growth factors, and ECM-modifying molecules to construct the PMN. Fibronectin acts as “furniture” helping DTCs attach[17].

After PMN formation, circulating tumor cells migrate and form metastatic niches, which are more developed “houses” with better oxygen and blood supply. These niches recruit hematopoietic progenitor cells, endothelial progenitor cells, and stromal growth factors, facilitating angiogenesis and tumor infiltration[15]. Metastatic niches regulate both tumor proliferation and dormancy. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a small subpopulation of tumor cells that possess the ability to self-renew and differentiate into multiple cell types within the tumor. These cells are thought to play a critical role in tumor initiation, progression, and resistance to therapy. In the context of tumor dormancy, CSCs are particularly important, as they have been shown to survive in a quiescent state within the TME, evading conventional treatments and potentially contributing to tumor recurrence. For example, Notch2 promotes quiescence in breast CSCs within the bone marrow niche while driving proliferation in the primary tumor[18]. Signals within niches can have opposing effects depending on the context.

ECM: The ECM is a complex, acellular protein network, rich in physical, chemical, and biological properties. It serves as a network that facilitates cell communication, transmits signals, and provides anchorage sites. The recently proposed concept of “the matrisome” (a collection of ECM and ECM-related proteins) refers to this collection in proteomics[19]. Many ECM-related proteins, such as tenascin-C, type I collagen, and fibronectin[20], can reach PMNs and act as cues before metastasis. The tumor-associated ECM is much more disordered and complex than the normal ECM because it is primarily influenced by the tumor rather than the normal body structures[21]. The ECM can influence tumor cell dormancy by acting as a niche. The tumor cell-derived ECM can serve as a pre-dormancy niche that promote dormancy. Tumor cells themselves actively participate in the assembly of this matrix.

Both the molecular and physical properties of the ECM play critical roles in tumor dormancy. Downregulation of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor blocks signaling pathways in cells and the ECM, hindering integrins’ ability to function in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells, inactivating mitotic pathway, and inducing dormancy in tumor cells. Perivascular ECM molecules, such as thrombospondin 1, can maintain dormancy in cancer cells[22].

Among the ECM components, collagen is most closely related to dormancy. Previous studies have shown that cross-linking between type I collagen deposition and integrin β1 or lysine oxidase (LOX) creates an ECM favorable for tumor cell proliferation, capable of reawakening dormant tumor cells[23]. This process is additionally amplified through the interplay between the tetraspanin transmembrane 4 L six family member 1 and discoidin domain receptor family member 1 - a collagen-binding receptor tyrosine kinase. This enhanced interaction increases the expression of stem-related factors such as SRY-box 2 and Nanog homeobox, thereby promoting the awakening of dormancy[24].

The signaling downstream of integrin β1 involves key kinases including focal adhesion kinase (FAK), non-receptor tyrosine kinase, extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK), and myosin light chain kinase. Integrin β1 mediates the transition from dormancy to proliferation. Specifically, it enables cancer cells to react to fibronectin production and subsequent signaling processes mediated by integrin β1, achieving this via the activation of myosin light chain kinase. This activation results in the production of actin stress fibers, driving subsequent proliferation.

This mechanistic cascade is evident in vivo. For instance, during the early stages of breast cancer cell metastasis to the lung, insufficient adhesion to the ECM inhibits proliferation. However, as the number of adherent plaques increases in the later stage, the integrin β1-FAK signaling pathway becomes activated, ultimately promoting tumor cell proliferation.

In contrast to type I collagen, type III collagen has the opposite effect on dormancy. Previous work showed that reducing type III collagen in the ECM increases breast tumor aggressiveness, while upregulation of its expression is associated with improved survival in breast cancer patients, suggesting that type III collagen can limit metastasis. The latest research points out that type III collagen is necessary to maintain tumor cell dormancy[25]. Previous studies have demonstrated many signaling pathways involved in tumor dormancy, such as transforming growth factor (TGF)-β2 and the retinoic acid pathway; however, new studies suggests that the collagen type III/discoidin domain receptor family member 1/Janus kinase 2/signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 pathway may act in parallel with these signals to enhance tumor dormancy. Changes in matrix metalloproteinase expression may lead to collagen remodeling and reactivation following dormancy. Hypoxia, a regulator of collagen type III expression, triggers this pathway to promote the formation of a pro-quiescent ECM niche[26].

Fibronectin, stiffness and mechanotransduction pathways of the ECM are also critical for regulating dormancy[27]. Fibronectin, a key ECM glycoprotein, is a critical mediator of cell adhesion, migration, and signaling in the TME[28]. It is abundantly secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts and other stromal cells, contributing to the fibrotic and rigid nature of tumor ECM. Fibronectin supports tumorigenesis by enhancing integrin-mediated signaling, which promotes cancer cell survival, proliferation, and invasion. In tumor dormancy, fibronectin can act as a double-edged sword: While it may initially suppress tumor growth by maintaining a quiescent state, its overexpression in the TME can eventually drive tumor reactivation and metastasis.

Matrix stiffness is a defining feature of the TME, often increasing during tumor progression due to excessive ECM deposition and cross-linking[29]. A soft ECM is beneficial for maintaining the stem cell properties of tumor cells. Integrin β1 and FAK signaling increase mitotic stimulation through the induction of protein kinase B and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. However, the regulation of dormancy by stiffness is complex. In a rigid environment, endothelial cells secrete the stromal-derived protein cysteine-rich angiogenesis inducer 61, which triggers β-catenin-dependent upregulation of N-cadherin expression levels, thereby enabling tumor cells to enter the bloodstream and undergo metastasis. Conversely, a hard ECM can also induce dormancy[30]. An in-depth single-cell analysis revealed that cells entering long-term dormancy stably adhered to rigid substrates through integrin α5β1 and rho-related kinase (ROCK) mediated cell tension[31].

Mechanotransduction pathways, such as integrin signaling, Yes-associated protein/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif activation, and Rho-ROCK-ERK signaling, are critical in translating mechanical cues into biochemical signals that regulate tumor behavior. Integrins, particularly α5β1 and αvβ3, are key mediators of mechanotransduction, linking ECM stiffness to intracellular signaling cascades[32]. In tumor dormancy, integrin signaling can maintain quiescence by suppressing proliferative pathways. However, in a stiff TME, integrin-mediated activation of Yes-associated protein/transcriptional co-activator with PDZ-binding motif and Rho-ROCK-ERK pathways can drive tumor reactivation and progression[33].

Fibronectin, matrix stiffness, and mechanotransduction pathways are intricately linked to the regulation of tumor dormancy and progression. Their interplay in the TME underscores the importance of targeting ECM dynamics and mechanobiology in cancer therapy.

The immune system plays a central role in maintaining the dynamic equilibrium of tumor cell dormancy and reactivation[34]. This balance can be viewed as a state of “truce”, where immune surveillance effectively suppresses but does not completely eliminate DTCs. Disruption of this equilibrium leads to either immune-mediated clearance or tumor recu

The maintenance of dormancy relies on the coordinated action of adaptive and innate immunity. Key mechanisms include: (1) CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, which suppress tumor proliferation through direct cytotoxicity and the secretion of cytokines like interferon (IFN)-γ. CD4+ T cells can also inhibit tumor growth and angiogenesis by producing chemokines such as chemokine ligand (CXCL) 9 and CXCL10; and (2) NK cells, which are a critical limiting factor for DTC dormancy. An expanded pool of activated NK cells [e.g., via interleukin (IL)-15 administration] upholds dormancy by upregulating the IFN-γ signaling pathway[35,36].

Conversely, potent immunosuppressive mechanisms within the TME can break this equilibrium and promote recurrence. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and regulatory T cells (Tregs) foster immune escape and proliferation by secreting immunosuppressive cytokines (e.g., IL-6), expressing checkpoint ligands like programmed death ligand 1, or directly inhibiting CD8+ T cell function. Furthermore, activated hepatic stellate cells can suppress NK cell activity via CXCL12 secretion, leading to the reactivation of DTCs[37-40].

The dormancy-permissive niche relies on a complex interplay between suppressive and cytotoxic immune populations to maintain immune homeostasis. Tregs, cytotoxic T cells, soluble cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4, gut microbiota-derived metabolites, NK T cells, and mechanical forces all contribute to this dynamic balance[41,42].

Chronic inflammation is a key driver that disrupts the immune balance and promotes escape from dormancy. The effect of inflammation on tumors is context-dependent, hinging on the type and duration of the inflammatory response. While acute or type I inflammation may induce or maintain dormancy by inhibiting proliferation, chronic or type II inflammation typically promotes tumorigenesis and dormant cell reactivation. For instance, neutrophil extracellular traps formed at sites of inflammation (e.g., lipopolysaccharide-induced pneumonia) have been shown to awaken dormant cancer cells. Thus, chronic, non-resolving inflammation creates a microenvironment favorable for reactivation[43,44].

Over the past few years, a growing body of research has started to explore the interaction between tumor development and stem cells. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are stromal cells with self-inheritance capabilities and multilineage differentiation potential. MSCs from different sources exhibit different characteristics. Whether MSCs promote or inhibit tumor progression and formation depends on their origin, the tumor type, and the microenvironment, making their role controversial[45].

Adipose tissue-derived MSCs promote the growth of breast, brain, gastric and ovarian tumors[46], but inhibit the growth of melanoma. The most studied bone marrow MSCs (BMSCs) can be categorized into tumor-derived BMSCs and BMSCs from other sources. Tumor-associated MSCs mainly play a tumor-promoting role, while BMSCs from other sources tend to have an anti-tumor effect. However, this rule is not absolute. The relationship between tumor dormancy and BMSCs has also been extensively studied in the field of anti-tumor research. During their migration to the tumor niche, MSCs can interact with tumor cells and adopt a cancer phenotype. Tumor-associated MSCs and BMSCs have different phenotypes, which may be regulated by factors in the TME, such as cancer cell factors and secreted proteins.

BMSCs can secrete a variety of microRNAs (miRNAs) and cytokines, including growth inhibitory specific protein 6, TGF-β family molecules, and CXCL12[47]. These bioactive molecules are capable of directly interacting with target cells or being indirectly sequestered in exosomes, thereby promoting the dormant state of DTCs and CSCs. MSCs can also protect dormant tumor cells in the BM by increasing Tregs, modulating the immune response to create an immunosuppressive environment, and decreasing NK cell activity[48].

Exosomes are extracellular vesicles produced by cells, with an average diameter of approximately 100 nm[49]. Exosomal cargo includes proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, such as mRNAs and non-coding RNAs[50]. Exosomes facilitate cell-to-cell information transfer by adhering to target cells, with effects that include promoting angiogenesis and drug resistance. Tumor cell-derived exosomes may be involved in the recruitment and remodeling of the microenvironment. Organ-specific cells uptake the exosomes and play an essential role in establishing PMNs, including vascular permeability, inflammation, and recruitment of myeloid progenitors. The adhesion molecules in these tumor-derived exosomes are mainly 6 members of the integrin family. The integrin composition of exosomes varies depending on the organ of origin. During the formation of lung cancer PMNs, exosomal integrin α6β4 activates the non-receptor tyrosine kinase-S100A4 axis, a signaling and inflammatory pathway in target cells. Exosomes can reprogram organs and foster the growth of metastatic cells. They can also activate the immune system via lymphatic vessels, mediating sentinel lymph node metastasis and promote PMN formation through ECM remodeling, angiogenesis, and tumor cell recruitment[51]. MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell-derived exosomes can target M2 tumor-supporting macrophages in axillary lymph nodes to regulate tumor growth and lymphatic metastasis. NK cell-derived exosomes in B16F10 cells can induce apoptosis to inhibit tumor growth. Recent studies have shown that exosomes also play an important role in the dormancy of tumor cells. Exosomes produced by MSCs affect the initial process of dormancy and dedifferentiation of breast cancer cells in the perivascular niche of the bone marrow[48]. Breast cancer cells can instruct MSCs to release exosomes with various miRNA cargoes, such as miR-222/223, to induce tumor circulation quiescence and promote a dormant state. Specifically, breast cancer cells activate MSCs by secreting specific signaling molecules, which in turn induces the MSCs to release exosomes. These exosomes deliver miRNAs and proteins that suppress the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, thereby inducing a dormant state in the breast cancer cells.

MSC-derived exosomes (MSC-exosomes) have emerged as promising tools for therapeutic delivery, particularly in complex environments like the TME and tumor dormancy. Their natural nanovesicle structure, biocompatibility, and ability to mediate intercellular communication make them ideal candidates for targeted therapy. However, to enhance their efficacy in these specific contexts, advanced engineering strategies have been developed.

Membrane modification is a critical strategy to improve the specificity and efficiency of MSC-exosomes in the TME. By altering the exosomal surface, researchers can enhance their ability to home in on tumor cells or dormant niches. The addition of bone-targeting peptides to exosomes has been shown to improve their delivery to specific cell types, such as osteoblasts in bone-related conditions[52]. This approach can be adapted to target tumor-associated cells or dormant tumor cells in the TME. Modifying exosomes with ligands that bind to receptors overexpressed in tumor cells (e.g., integrins or growth factor receptors) can enhance their uptake and therapeutic impact. This strategy is particularly useful for overcoming the heterogeneous nature of the TME.

Loading MSC-exosomes with therapeutic nanoparticles or bioactive molecules can amplify their therapeutic potential. This approach allows for precise control over the release and activity of the cargo within the TME or dormant tumor niches. Exosomes engineered to carry siRNA or miRNA can silence specific genes involved in tumor progression or dormancy. For example, siRNA targeting the Shn3 gene in osteoblasts has shown promise in enhancing osteogenic differentiation and inhibiting osteoclast formation. Similarly, miRNA-125a-5p has been demonstrated to promote cardioprotection and angiogenesis, which could be adapted to modulate the TME[53]. Encapsulating cytokines, chemokines, or small molecules within exosomes can modulate immune responses or disrupt dormant tumor cell survival mechanisms. This strategy is particularly relevant for addressing the immunosuppressive nature of the TME.

Combining MSC-exosomes with biomaterials, such as hydrogels or nerve conduits, can provide sustained release and localized delivery of therapeutic cargo[54]. This approach is particularly beneficial for targeting dormant tumor cells, which often reside in specific niches within the TME.

Tumors rely on blood vessels to supply oxygen and nutrients while removing waste products. The tumor vasculature differs from ordinary tissues, characterized by necrosis of newly formed blood vessels, which leads to hypoxia, metabolic deficiencies, and an imbalance in the expression of angiogenic factors, ultimately leading to abnormal angiogenesis[55]. If the tumor fails to achieve sufficient angiogenic potential during its growth, the pro-angiogenic and anti-angiogenic effects reach equilibrium, inducing a state known as angiogenic dormancy. During this period, tumor cell proliferation is balanced by enhanced induction of apoptosis. Conversely, when the tumor acquires angiogenic potential, leading to the growth of vascularized tumors, this transition is referred to as an angiogenic switch, also known as an angiogenic phenotype.

The transition between the angiogenic switch and angiogenic dormancy is regulated by microenvironmental factors, including the pro-angiogenic platelet-derived growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), anti-angiogenic endostatin, angiostatins and thrombospondin-1 (THBS1). VEGF and the morphogenesis of blood vessels are associated with vascular homeostasis and of endothelial cell differentiation[56]. The release of VEGF activates endothelial cells to secrete cytokines such as IL-6, IL-3, granulocyte-CSF, granulocyte-macrophage-CSF, and nitric oxide. These factors promote prostate cancer cell proliferation, emphasizing the role of activated angiogenic endothelial cells in facilitating tumor cells escape dormancy. THBS1 is a tumor suppressor that results in reduced primary tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis. Using proteomic analysis of proteins in the microvascular niche, THBS1 stabilizes the microvasculature to maintain tumor dormancy. Pro-angiogenic factors secreted by newly formed blood vessels lead to reduced THBS1 expression and increased expression of TGF-β1 and periostin, leading to the proliferation of DTCs.

CSCs can directly promote the formation of abnormal blood vessels and also induce a significant increase in VEGF levels, directly generating or stimulating the pro-angiogenic activity of stromal cells near the niche[57]. Some factors related to stem cells, including Notch, also serve as promoters of angiogenesis. In contrast, anti-angiogenic factors correlate with the inactivation of transcription factors associated with stem cells, which in turn promotes dormancy.

Similar to inflammatory responses, hypoxia exerts a dual effect on the regulation of tumor dormancy[1]. The phenotypic heterogeneity of DTCs is pre-set by the hypoxic microenvironment of the primary tumor, which generates dormant DTC subpopulations that evade treatment. Hypoxia commonly promotes angiogenesis, tumor proliferation, metastasis, and reactivation after dormancy[58]. Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor (LIFR) serves as both a tumor suppressor and a metastasis suppressor, inducing a dormant phenotype in bone-disseminated breast cancer cells. Hypoxia downregulates the expression of LIFR, which is inversely correlated with the expression level of LIFR mRNA. Additionally, hypoxia-induced LOX activation promotes tumor cell metastasis. LOX cross-links type IV collagen and elastin within the ECM, facilitating ECM remodeling to form metastatic niches and supporting the invasion of bone marrow-derived cells. At the same time, hypoxia may selectively induce the selective expression of dormancy-promoting genes to maintain dormancy through specific genetic programming.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) is a key transcriptional regulator that enables cells to adapt to low oxygen conditions by activating downstream genes involved in cell survival, metabolism, and angiogenesis. Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α is stabilized and translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a heterodimer with HIF-1β. This complex binds to hypoxia-responsive elements in the promoters of target genes, initiating their transcription[59]. While it promotes tumor cell survival and dormancy in hypoxic microenvironments, it also contributes to tumor progression and metastasis by enhancing angiogenesis and invasion[60]. Therapeutic strategies targeting HIF-1α, such as HIF prolyl hydroxylase inhibitors or HIF-1α antagonists, are being explored to disrupt dormancy and sensitize cancer cells to treatment.

The pH of the TME is usually acidic. This acidity is closely linked to poor prognosis, induces chemo- and radio-resistant phenotypes, and suppresses the tumoricidal activity of cytotoxic lymphocytes and NK cells, thereby facilitating dormancy. The “Warburg Hypothesis”, proposed a century ago, posits that tumors rely on glycolysis to sustain proliferation even in the presence of sufficient oxygen to support mitochondrial function. Acidosis has been recognized as one of the defining hallmarks of the TME. The effects of acidosis mainly include the promotion of low replication rate, apoptosis, high resistance to autophagy, tumor invasion, angiogenesis, and immune evasion.

An acidic microenvironment can promote low replication rates, apoptosis, high resistance to autophagy, ultimately leading to dormancy. The acidic TME fosters a hyperproliferative phenotype even in the presence of abundant growth factors. Acidity increases the proportion of cells in the G0 phase, diminishes the ability of serum to stimulate the Raf/ERK/mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 kinase pathway, and modulates growth factor signaling. Extracellular acidity affects intracellular pH, which in turn directly regulates the cell cycle. Under persistent extracellular acidosis, intracellular pH declines, restricting G2/M entry through reduced activity of cyclin-dependent kinase 1-cyclin B1. Lactic acid induces TGF-β2 transcription and protein secretion in glioma cells, while acidity enhances TGF-β secretion and signal transduction in MSCs. Acidity promotes a typical epithelial-mesenchymal transition program in melanoma cells, promoting reduced levels of proliferation, resistance to apoptosis, and high metalloproteinase-dependent invasiveness, all of which contribute to dormancy. Acidity activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway, resulting in protection against cytotoxicity-induced apoptosis. Autophagy enables cells to recycle self-digesting cytoplasmic proteins and organelles, promoting cell survival during periods of frequent nutrient restriction and hypoxia. Acidic tumor cells inhibit autophagy, resulting in diminished viability.

Acid-sensing ion channels (ASICs) are a family of ion channels that belong to the degenerin/epithelial sodium channel superfamily. They are primarily activated by extracellular protons (H+) and play a role in sensing acidosis in various physiological and pathological conditions. The acidic TME can activate ASICs, particularly ASIC1 and ASIC3, which are expressed in various cancer cell types. Activation of these channels can influence cellular processes such as proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. In the context of tumor dormancy, ASICs may help maintain cancer cells in a quiescent state by modulating intracellular signaling pathways and cellular metabolism.

Acidity also promotes tumor invasion. Acid-activated tumors amplify the protease cascade by activating urokinase-type plasminogen activator, which converts plasminogen to plasmin and degrades the ECM various components, and activates latent collagenase and growth factors. The acidic environment also enhances the degradative properties of matrix metalloproteinases and tumor heparanase, which degrade the ECM and help tumor cells migrate. During the initial stages of adaptation to the microenvironment, acid-promoted invasiveness facilitates tumor cell retention at new sites or metastasizing.

The TME exerts a profound influence on tumor dormancy by orchestrating cellular and molecular interactions. Key components such as the ECM, immune cells, and signaling pathways create niches that regulate dormancy[61]. For example, ECM components like type I collagen can awaken dormant cells, while type III collagen maintains quiescence[62]. Immune cells, including CD8+ T cells and NK cells, suppress reactivation, while Tregs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells promote proliferation. Additionally, factors like hypoxia, acidosis, and angiogenic imbalances dynamically modulate dormancy. These findings highlight the TME’s pivotal role in sustaining or disrupting dormancy, offering potential therapeutic targets.

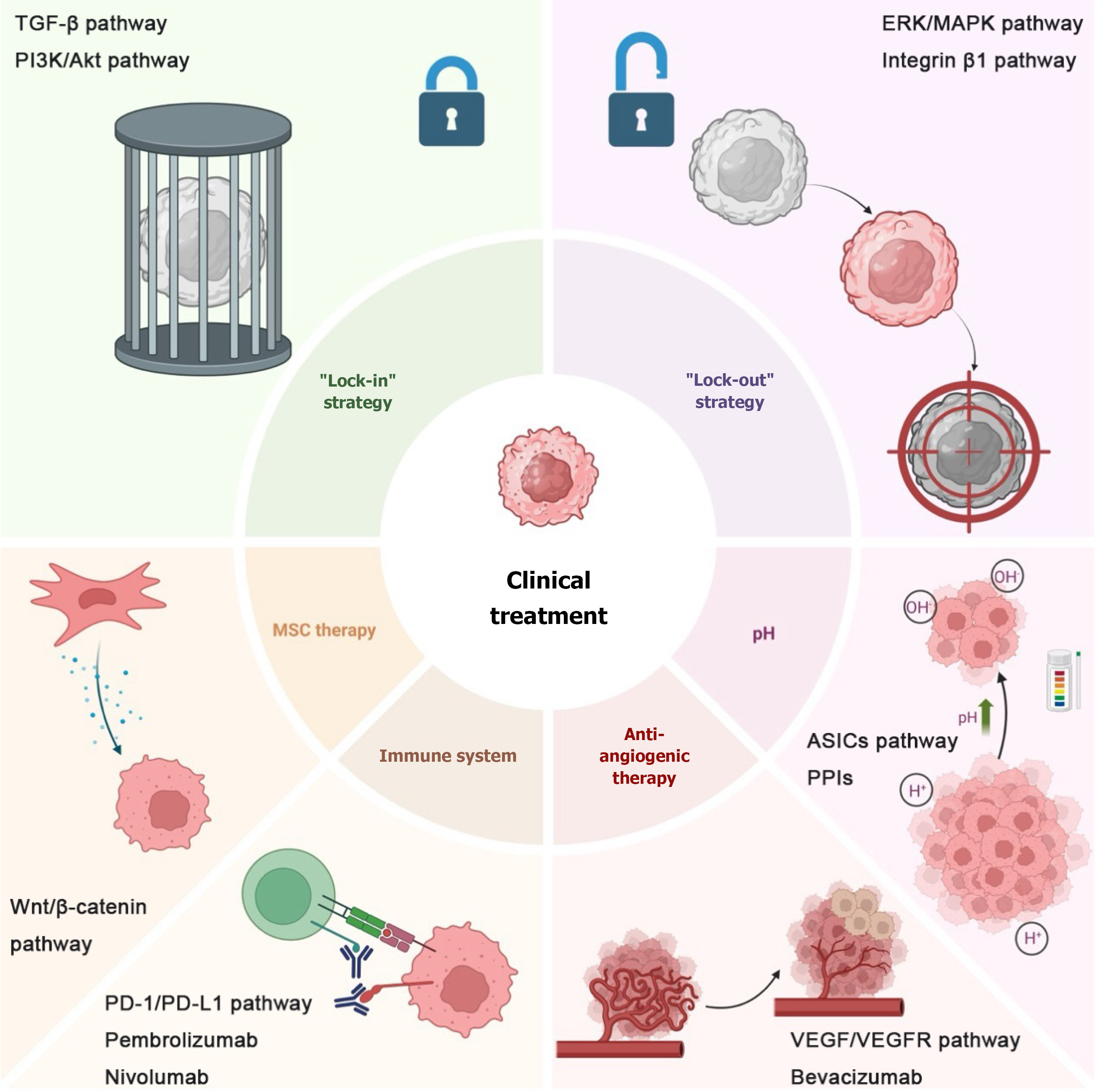

Although numerous approaches have been developed to treat tumors, metastasis and recurrence frequently occur after a period of treatment. Dormant tumor cells are believed to be a primary contributor to treatment failure, and two widely recognized treatment strategies have been proposed: “Lock-out” and “lock-in” strategies[10]. Since dormancy serves as a mechanism by which cancer cells evade current traditional antiproliferative therapies, the aim of the “lock-out” strategy is to reawaken dormant cells and compel them to proliferate before treatment. This approach increases the sensitivity of tumor cells to conventional chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy. The “lock-in” strategy refers to maintaining tumor cells in a state of permanent dormancy, preventing their reactivation and thereby inhibiting metastasis or recurrence (Figure 2). The “lock-out” and “lock-in” strategies are key concepts in managing tumor dormancy. The “lock-out” approach focuses on keeping dormant tumor cells in a quiescent state, which can be achieved through therapies that reinforce tumor cell dormancy, such as targeting metabolic pathways or immune modulation. The “lock-in” strategy, on the other hand, aims to activate dormant cells and make them susceptible to conventional therapies. Current clinical trials are investigating the effectiveness of combining these strategies with immune checkpoint inhibitors, targeted therapies, and other treatments to improve patient outcomes.

Beyond these two strategies, this paper starts from a novel perspective: Targeting the TME of dormant tumor cells. The microenvironment affects the ability of dormant tumor cells to evade immune responses and survive, complicating tumor target identification. Therefore, attempts to deprive dormant tumor cells of their microenvironmental support or to disrupt their microenvironmental homeostasis may lead to the development of new therapeutic strategies to achieve therapeutic goals. Therapies targeting various components of the TME have been studied, but most remain at the preclinical stage. This paper summarizes some of the more mature approaches and discusses their latest research progress.

With the rapid development of stem cell-based treatment methods and molecular biology in recent years, the research on MSCs for anti-tumor has made great progress[63,64]. MSCs regulate tumor biological activities such as through paracrine mechanisms. For instance, adipose tissue-derived MSCs can inhibit the growth of lung cancer cells by secreting cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand and IFN-β[65]. Among them, the most in-depth study is bone marrow MSCs, which can be used to regulate tumor dormancy, thereby preventing or delaying cancer recurrence. We summarize the potential clinical applications of MSCs for the treatment of dormant tumor cells.

BMSCs can directly inhibit the growth of certain tumors by suppressing vasculature formation or cell cycle progression. Engineered MSCs have also been used as targeted anticancer vectors for gene therapy, offering enhanced efficacy and safety compared to unmodified MSCs[46]. BMSCs and their exosomes can be used as carriers for targeting cancer. BMSCs are able to home to the site of tissue injury and the TME by reducing immune inflammatory responses. Therefore, they can be used as carriers to deliver nanoparticles, antitumor drugs, proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNA and miRNA. For example, the internalization of paclitaxel-loaded nanoparticles into BMSCs resulted in favorable antitumor efficacy, which was caused by the sustained release of encapsulated paclitaxel into the TME. Inhibitory miRNAs such as antagomiR-222/223 can induce mammary CSCs to enter a dormant state. At the same time, the exosomes of MSCs have the ability to bind to the plasma membrane, are easy to isolate, and exhibit strong stability, allowing them to deliver drugs to designated sites.

According to existing research, targeting the key role of MSCs in the interaction with tumor cells can interfere with the formation of tumor dormancy. So far, targeted therapy has been widely used in the clinic as more and more key roles in regulating specific metastasis and dormancy have been discovered[66]. BMSCs can interact with CSCs and induce them into a circulating dormant state by secreting proteins, exosomes, and cytokines, which would render these CSCs resistant to targeted therapy. To sensitize CSCs to targeted drugs, the interaction between CSCs and MSCs needs to be disrupted[67]. Among the most promising approaches to mitigate bone metastases is targeting dormancy-associated niches. Bone metastases are regarded as a marker of unfavorable prognosis, and following the definition of the bone metastasis niche concept - which encompasses connective tissue, bone stromal cells, and signaling molecules (e.g., bone morphogenetic protein 7, TGF-β2, growth inhibitory specific protein 6)[47] - several studies have suggested that targeting this niche could prevent or delay the occurrence of bone metastasis. Specifically, targeting the bone metastatic niche can disrupt the crosstalk between MSCs and tumor cells, thereby suppressing the development of tumor dormancy, an approach recognized as a novel therapeutic strategy.

Adaptive immunity maintains tumor cells in a functional dormant state, and immunostimulatory therapy can effectively prevent metastasis by prolonging DTC dormancy[68]. The latest discovery and Food and Drug Administration approval of immune checkpoint inhibitors mark a new direction in cancer treatment[69]. Dormant DTCs are known to form well-established mechanisms for evading the immune system. Dormant DTCs downregulate major histocompatibility complex class I to escape CD8+ T cell recognition. The microenvironment suppresses the immune system by protecting cancer cells from oxidative stress or through the expression of checkpoint ligands such as programmed death ligand 1 and the secretion of immunosuppressive cytokines such as IL-6. Several related vaccines are available. Vaccines against tumor-associated blood vessel Ags can activate T-cell-dependent immunity, induce tumor regression, or maintain dormancy to prolong overall survival. Vaccination of mice with leukemia with cells transduced with CXCL10 induces NK cells to express programmed death ligand 1, which activates T cells to eliminate dormant cells.

Recent advances in immunotherapy, particularly the development of bispecific antibodies and chimeric antigen receptor NK cells, offer promising strategies for targeting dormant tumor cells[70-73]. Bispecific antibodies, such as blinatumomab, engage both tumor antigens and T cells to restore immune surveillance, while chimeric antigen receptor NK cells, engineered to express tumor-targeting receptors, enhance cytotoxicity against dormant tumor cells, providing new opportunities for overcoming immune evasion during dormancy.

Many other components in various TMEs can also be used as therapeutic targets to modulate dormancy, but related studies have not yet achieved stable effects. For example, anti-angiogenic therapy may reduce the proportion of CSCs in different tumors, making it a promising treatment, albeit with conflicting results[74]. The VEGF-specific antibody bevacizumab can reduce metastatic niche formation in rectal cancer patients, and its combination with an anti-hepatocellular carcinoma-derived growth factor antibody can promote dormancy in a non-small cell lung cancer xenograft tumor model. However, antiangiogenic drugs often induce tumor hypoxia, allowing CSCs to survive and multiply, thereby promoting tumor progression. For instance, bevacizumab combined with the VEGF receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor sunitinib induces tumor hypoxia in breast cancer cell lines and increases the CSC population. Studies have shown that buffering the low pH at the tumor site through in vivo administration of esomeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, improves tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte effector function and delays tumor progression in melanoma. Inhibition of proton pumps on tumor cells with another proton pump inhibitor, pantoprazole, hindered tumor-induced macrophage suppression in vitro and in vivo. Neutralizing tumor pH with bicarbonate impairs cancer growth in mice, an effect associated with increased T-cell infiltration in tumor masses. However, its role in dormancy remains unclear.

Moreover, modulating the immune system through dietary changes can also promote dormancy. Low body weight is known to be associated with a reduced incidence of cancer. It is widely believed that obesity-related inflammation promotes cancer progression. Obesity leads to neutrophil infiltration in murine lungs, resulting in an increase in breast cancer metastasis to this site. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and IL-5 are responsible for the pro-metastatic effects of obesity. Lung inflammation and metastasis are reduced in mice fed a low-fat diet. Perioperative administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to mice significantly inhibited the growth of dormant metastatic breast cancer cells[75].

To enhance the critical analysis of current research, it is essential to compare the strengths and limitations of existing therapeutic strategies for targeting tumor dormancy. The “lock-in” strategy offers long-term control by maintaining tumor cells in a dormant state, thereby minimizing the risk of recurrence. However, its success depends heavily on understanding and sustaining the complex TME, which is dynamic and prone to disruption. Conversely, the “lock-out” approach aims to awaken dormant cells, making them susceptible to conventional therapies. While this strategy is more aggressive, it risks stimulating widespread proliferation if treatment timing is suboptimal.

A variety of targeted therapeutic strategies that utilize the TME to regulate tumor dormancy for cancer eradication are under development and validation. Numerous related therapeutic approaches have been explored for common metastatic cancer types. For instance, in breast cancer bone metastasis, the use of bisphosphonates (such as zoledronic acid) or RANKL inhibitors (like denosumab) to suppress osteoclast activity can break the “vicious cycle”, reducing bone resorption and reactivation of tumor cells[76]. Hypoxia-activated prodrugs (e.g., tirapazamine) and hypoxia-responsive nanomedicines are employed to enhance chemotherapy efficacy. For example, the hypoxia-amplifying polymer nanoprodrug nanoscale prodrug induces in-situ thrombosis, exacerbating tumor hypoxia, thereby activating the prodrug and inhibiting tumor growth[77]. The combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-programmed death 1 antibodies) with nanomedications can reverse the immunosuppressive state of the TME and promote T cell-mediated antitumor activity[78]. Additionally, gene silencing strategies targeting Siglec-15 have been shown to inhibit osteoclast activity and restore bone homeostasis.

Current immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, demonstrate promise in targeting DTCs, yet they face challenges in overcoming immune evasion mechanisms within the TME[79]. Similarly, MSC-based therapies hold potential for disrupting dormancy-related niches, but their dual roles in promoting and inhibiting tumors remain controversial. While the clinical application of dormancy-targeting strategies remains in its infancy, emerging studies provide valuable insights. For instance, immune checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab have shown success in prolonging progression-free survival in metastatic cancers, but their efficacy in targeting dormant DTCs is less consistent due to immune evasion mechanisms. In breast cancer, therapies combining anti-angiogenic agents such as bevacizumab with chemotherapy have demonstrated reductions in metastatic niche formation, yet challenges persist in avoiding tumor hypoxia and CSC activation. A notable example involves MSC-based delivery systems, which enhanced drug delivery to dormant cells in preclinical models. Despite these advances, translating these findings into reliable clinical outcomes requires further trials addressing toxicity, delivery precision, and the dynamic nature of the TME. Future research should integrate multidisciplinary approaches to refine these strategies, address their limitations, and explore synergistic combinations to achieve durable therapeutic outcomes.

There has been a wealth of research on tumor dormancy, and with the deepening and comprehensive understanding of the TME, connections between the two are constantly being uncovered. In the past, the treatment of dormant tumor cells primarily focused on molecular pathways. However, we can now implement strategies to target different parts of the TME to promote long-term dormancy in tumor cells or to facilitate their exit from dormancy, making them sensitive to treatment. Relevant research holds significant clinical application prospects, which could fundamentally change treatment methods and survival rates for cancer patients. Although the importance of the microenvironment in tumor dormancy has been confirmed, numerous research challenges remain. The following are key issues that require urgent resolution: Currently, real-time tracking techniques for dormant tumor cells are still underdeveloped. Developing in vivo imaging technologies capable of precisely monitoring the dynamic changes of dormant cells remains a key focus for future research. The heterogeneity of the microenvironment presents a challenge for developing tissue-specific treatments. For instance, the role of hepatic stellate cells in liver metastasis may differ from the microenvironmental mechanisms involved in lung or bone metastases. Therefore, there is a need to develop therapeutic strategies that can adapt to different microenvironments. Further research is needed to understand how cellular and molecular interactions within the microenvironment evolve over time and influence tumor dormancy. For example, the specific mechanisms linking the contraction of the NK cell pool to tumor reactivation have not yet been fully elucidated. Nonetheless, the roles of many parts of the TME in tumor dormancy remain unclear, meaning many studies are still in the laboratory phase, with clinical trials and applications yet to be conducted.

While the critical role of the TME in cancer progression is well-established, this review has specifically delineated its function as a central regulator of tumor cell dormancy, a key mediator of metastatic relapse. Moving beyond a mere catalog of individual components, we have synthesized the complex, and often opposing, roles of ECM constituents, immune cells, and soluble factors into an integrated framework that illustrates how dynamic interactions within the TME dictate the dormant vs proliferative switch.

The primary novelty of this perspective lies in framing therapeutic strategies through the lens of modulating the TME to control dormancy. Unlike conventional therapies that primarily target proliferating cells, we have critically evaluated the potential of the “lock-in” and “lock-out” paradigms, which aim to therapeutically manipulate the niche itself. This approach represents a paradigm shift from directly attacking tumor cells to influencing their contextual signals for therapeutic gain.

Furthermore, we have highlighted the dual nature and contextual dependency of many microenvironmental factors - such as the opposing effects of different collagen types, or the balance between immune surveillance and suppression - emphasizing that future therapeutic success will depend on a precise understanding of these interactions. Although translating these strategies to the clinic faces challenges, including the dynamic nature of the TME and the difficulty in detecting dormant cells, this review underscores that targeting the supportive niche of dormant cells offers a promising, and arguably essential, avenue to prevent recurrence and improve long-term patient survival. Ultimately, mastering the language of the TME may hold the key to locking away the threat of metastatic disease.

| 1. | Omokehinde T, Johnson RW. Dormancy in the Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1329:35-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Deng YR, Wu QZ, Zhang W, Jiang HP, Xu CQ, Chen SC, Fan J, Guo SQ, Chen XJ. Apoptotic cell-derived extracellular vesicles-MTA1 confer radioresistance in cervical cancer by inducing cellular dormancy. J Transl Med. 2025;23:328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sosa MS, Bragado P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA. Mechanisms of disseminated cancer cell dormancy: an awakening field. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:611-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 743] [Cited by in RCA: 898] [Article Influence: 74.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dasgupta A, Lim AR, Ghajar CM. Circulating and disseminated tumor cells: harbingers or initiators of metastasis? Mol Oncol. 2017;11:40-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Páez D, Labonte MJ, Bohanes P, Zhang W, Benhanim L, Ning Y, Wakatsuki T, Loupakis F, Lenz HJ. Cancer dormancy: a model of early dissemination and late cancer recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:645-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gomis RR, Gawrzak S. Tumor cell dormancy. Mol Oncol. 2017;11:62-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Recasens A, Munoz L. Targeting Cancer Cell Dormancy. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2019;40:128-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 36.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Attaran S, Bissell MJ. The role of tumor microenvironment and exosomes in dormancy and relapse. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;78:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Paget S. The distribution of secondary growths in cancer of the breast. 1889. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1989;8:98-101. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Sistigu A, Musella M, Galassi C, Vitale I, De Maria R. Tuning Cancer Fate: Tumor Microenvironment's Role in Cancer Stem Cell Quiescence and Reawakening. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Izraely S, Witz IP. Site-specific metastasis: A cooperation between cancer cells and the metastatic microenvironment. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:1308-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pawlik TM, Keyomarsi K. Role of cell cycle in mediating sensitivity to radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;59:928-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 669] [Cited by in RCA: 822] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Flaberg E, Markasz L, Petranyi G, Stuber G, Dicso F, Alchihabi N, Oláh È, Csízy I, Józsa T, Andrén O, Johansson JE, Andersson SO, Klein G, Szekely L. High-throughput live-cell imaging reveals differential inhibition of tumor cell proliferation by human fibroblasts. Int J Cancer. 2011;128:2793-2802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peinado H, Zhang H, Matei IR, Costa-Silva B, Hoshino A, Rodrigues G, Psaila B, Kaplan RN, Bromberg JF, Kang Y, Bissell MJ, Cox TR, Giaccia AJ, Erler JT, Hiratsuka S, Ghajar CM, Lyden D. Pre-metastatic niches: organ-specific homes for metastases. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:302-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1003] [Cited by in RCA: 1424] [Article Influence: 158.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kaplan RN, Riba RD, Zacharoulis S, Bramley AH, Vincent L, Costa C, MacDonald DD, Jin DK, Shido K, Kerns SA, Zhu Z, Hicklin D, Wu Y, Port JL, Altorki N, Port ER, Ruggero D, Shmelkov SV, Jensen KK, Rafii S, Lyden D. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature. 2005;438:820-827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2613] [Cited by in RCA: 2447] [Article Influence: 116.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cox TR, Rumney RMH, Schoof EM, Perryman L, Høye AM, Agrawal A, Bird D, Latif NA, Forrest H, Evans HR, Huggins ID, Lang G, Linding R, Gartland A, Erler JT. The hypoxic cancer secretome induces pre-metastatic bone lesions through lysyl oxidase. Nature. 2015;522:106-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 377] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 35.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Psaila B, Lyden D. The metastatic niche: adapting the foreign soil. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:285-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 902] [Cited by in RCA: 971] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Capulli M, Hristova D, Valbret Z, Carys K, Arjan R, Maurizi A, Masedu F, Cappariello A, Rucci N, Teti A. Notch2 pathway mediates breast cancer cellular dormancy and mobilisation in bone and contributes to haematopoietic stem cell mimicry. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:157-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kai F, Drain AP, Weaver VM. The Extracellular Matrix Modulates the Metastatic Journey. Dev Cell. 2019;49:332-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 69.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Taha IN, Naba A. Exploring the extracellular matrix in health and disease using proteomics. Essays Biochem. 2019;63:417-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nouri K, Piryaei A, Seydi H, Zarkesh I, Ghoytasi I, Shokouhian B, Najimi M, Vosough M. Fibrotic liver extracellular matrix induces cancerous phenotype in biomimetic micro-tissues of hepatocellular carcinoma model. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2025;24:92-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hebert JD, Myers SA, Naba A, Abbruzzese G, Lamar JM, Carr SA, Hynes RO. Proteomic Profiling of the ECM of Xenograft Breast Cancer Metastases in Different Organs Reveals Distinct Metastatic Niches. Cancer Res. 2020;80:1475-1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cox TR, Bird D, Baker AM, Barker HE, Ho MW, Lang G, Erler JT. Editor's Note: LOX-Mediated Collagen Cross-linking Is Responsible for Fibrosis-Enhanced Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2019;79:5124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gao H, Chakraborty G, Zhang Z, Akalay I, Gadiya M, Gao Y, Sinha S, Hu J, Jiang C, Akram M, Brogi E, Leitinger B, Giancotti FG. Multi-organ Site Metastatic Reactivation Mediated by Non-canonical Discoidin Domain Receptor 1 Signaling. Cell. 2016;166:47-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Di Martino JS, Nobre AR, Mondal C, Taha I, Farias EF, Fertig EJ, Naba A, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, Bravo-Cordero JJ. A tumor-derived type III collagen-rich ECM niche regulates tumor cell dormancy. Nat Cancer. 2022;3:90-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Coelho NM, McCulloch CA. Mechanical signaling through the discoidin domain receptor 1 plays a central role in tissue fibrosis. Cell Adh Migr. 2018;12:348-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Aguirre-Ghiso JA. How dormant cancer persists and reawakens. Science. 2018;361:1314-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Guerrero-Barberà G, Burday N, Costell M. Shaping Oncogenic Microenvironments: Contribution of Fibronectin. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2024;12:1363004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mierke CT. Extracellular Matrix Cues Regulate Mechanosensing and Mechanotransduction of Cancer Cells. Cells. 2024;13:96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Liu Y, Lv J, Liang X, Yin X, Zhang L, Chen D, Jin X, Fiskesund R, Tang K, Ma J, Zhang H, Dong W, Mo S, Zhang T, Cheng F, Zhou Y, Xie J, Wang N, Huang B. Fibrin Stiffness Mediates Dormancy of Tumor-Repopulating Cells via a Cdc42-Driven Tet2 Epigenetic Program. Cancer Res. 2018;78:3926-3937. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Barney LE, Hall CL, Schwartz AD, Parks AN, Sparages C, Galarza S, Platt MO, Mercurio AM, Peyton SR. Tumor cell-organized fibronectin maintenance of a dormant breast cancer population. Sci Adv. 2020;6:eaaz4157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sun M, Chi G, Xu J, Tan Y, Xu J, Lv S, Xu Z, Xia Y, Li L, Li Y. Extracellular matrix stiffness controls osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells mediated by integrin α5. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li Y, Randriantsilefisoa R, Chen J, Cuellar-Camacho JL, Liang W, Li W. Matrix Stiffness Regulates Chemosensitivity, Stemness Characteristics, and Autophagy in Breast Cancer Cells. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3:4474-4485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Correia AL, Guimaraes JC, Auf der Maur P, De Silva D, Trefny MP, Okamoto R, Bruno S, Schmidt A, Mertz K, Volkmann K, Terracciano L, Zippelius A, Vetter M, Kurzeder C, Weber WP, Bentires-Alj M. Hepatic stellate cells suppress NK cell-sustained breast cancer dormancy. Nature. 2021;594:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Lan Q, Peyvandi S, Duffey N, Huang YT, Barras D, Held W, Richard F, Delorenzi M, Sotiriou C, Desmedt C, Lorusso G, Rüegg C. Type I interferon/IRF7 axis instigates chemotherapy-induced immunological dormancy in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2019;38:2814-2829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wang X, Lu XL, Zhao HY, Zhang FC, Jiang XB. A novel recombinant protein of IP10-EGFRvIIIscFv and CD8(+) cytotoxic T lymphocytes synergistically inhibits the growth of implanted glioma in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62:1261-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wculek SK, Malanchi I. Neutrophils support lung colonization of metastasis-initiating breast cancer cells. Nature. 2015;528:413-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 726] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Albrengues J, Shields MA, Ng D, Park CG, Ambrico A, Poindexter ME, Upadhyay P, Uyeminami DL, Pommier A, Küttner V, Bružas E, Maiorino L, Bautista C, Carmona EM, Gimotty PA, Fearon DT, Chang K, Lyons SK, Pinkerton KE, Trotman LC, Goldberg MS, Yeh JT, Egeblad M. Neutrophil extracellular traps produced during inflammation awaken dormant cancer cells in mice. Science. 2018;361:eaao4227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 979] [Cited by in RCA: 1136] [Article Influence: 142.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Coffelt SB, Kersten K, Doornebal CW, Weiden J, Vrijland K, Hau CS, Verstegen NJM, Ciampricotti M, Hawinkels LJAC, Jonkers J, de Visser KE. IL-17-producing γδ T cells and neutrophils conspire to promote breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2015;522:345-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1232] [Cited by in RCA: 1413] [Article Influence: 128.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Malladi S, Macalinao DG, Jin X, He L, Basnet H, Zou Y, de Stanchina E, Massagué J. Metastatic Latency and Immune Evasion through Autocrine Inhibition of WNT. Cell. 2016;165:45-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Osaki M, Sakaguchi S. Soluble CTLA-4 regulates immune homeostasis and promotes resolution of inflammation by suppressing type 1 but allowing type 2 immunity. Immunity. 2025;58:889-908.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Ifejeokwu OV, Do AH, El Khatib SM, Ho NN, Zavala A, Othy S, Acharya MM. Immune checkpoint inhibition perturbs neuro-immune homeostasis and impairs cognitive function. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2025;44:183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Tsilimigras DI, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Moris D, Pawlik TM. Liver Tumor Microenvironment. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1296:227-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Manjili SH, Isbell M, Ghochaghi N, Perkinson T, Manjili MH. Multifaceted functions of chronic inflammation in regulating tumor dormancy and relapse. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;78:17-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Timaner M, Tsai KK, Shaked Y. The multifaceted role of mesenchymal stem cells in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020;60:225-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Li JN, Li W, Cao LQ, Liu N, Zhang K. Efficacy of mesenchymal stem cells in the treatment of gastrointestinal malignancies. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12:365-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 47. | Hu W, Zhang L, Dong Y, Tian Z, Chen Y, Dong S. Tumour dormancy in inflammatory microenvironment: A promising therapeutic strategy for cancer-related bone metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77:5149-5169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sandiford OA, Donnelly RJ, El-Far MH, Burgmeyer LM, Sinha G, Pamarthi SH, Sherman LS, Ferrer AI, DeVore DE, Patel SA, Naaldijk Y, Alonso S, Barak P, Bryan M, Ponzio NM, Narayanan R, Etchegaray JP, Kumar R, Rameshwar P. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Secreted Extracellular Vesicles Instruct Stepwise Dedifferentiation of Breast Cancer Cells into Dormancy at the Bone Marrow Perivascular Region. Cancer Res. 2021;81:1567-1582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Hoshino A, Costa-Silva B, Shen TL, Rodrigues G, Hashimoto A, Tesic Mark M, Molina H, Kohsaka S, Di Giannatale A, Ceder S, Singh S, Williams C, Soplop N, Uryu K, Pharmer L, King T, Bojmar L, Davies AE, Ararso Y, Zhang T, Zhang H, Hernandez J, Weiss JM, Dumont-Cole VD, Kramer K, Wexler LH, Narendran A, Schwartz GK, Healey JH, Sandstrom P, Labori KJ, Kure EH, Grandgenett PM, Hollingsworth MA, de Sousa M, Kaur S, Jain M, Mallya K, Batra SK, Jarnagin WR, Brady MS, Fodstad O, Muller V, Pantel K, Minn AJ, Bissell MJ, Garcia BA, Kang Y, Rajasekhar VK, Ghajar CM, Matei I, Peinado H, Bromberg J, Lyden D. Tumour exosome integrins determine organotropic metastasis. Nature. 2015;527:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2697] [Cited by in RCA: 3979] [Article Influence: 361.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367:eaau6977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6920] [Cited by in RCA: 7587] [Article Influence: 1264.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 51. | Wortzel I, Dror S, Kenific CM, Lyden D. Exosome-Mediated Metastasis: Communication from a Distance. Dev Cell. 2019;49:347-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 484] [Cited by in RCA: 972] [Article Influence: 162.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Cui Y, Guo Y, Kong L, Shi J, Liu P, Li R, Geng Y, Gao W, Zhang Z, Fu D. A bone-targeted engineered exosome platform delivering siRNA to treat osteoporosis. Bioact Mater. 2022;10:207-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Gao L, Qiu F, Cao H, Li H, Dai G, Ma T, Gong Y, Luo W, Zhu D, Qiu Z, Zhu P, Chu S, Yang H, Liu Z. Therapeutic delivery of microRNA-125a-5p oligonucleotides improves recovery from myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice and swine. Theranostics. 2023;13:685-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Li Q, Zhang F, Fu X, Han N. Therapeutic Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes as Nanomedicine for Peripheral Nerve Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:7882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51728] [Cited by in RCA: 48820] [Article Influence: 3254.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (12)] |

| 56. | Lee S, Chen TT, Barber CL, Jordan MC, Murdock J, Desai S, Ferrara N, Nagy A, Roos KP, Iruela-Arispe ML. Autocrine VEGF signaling is required for vascular homeostasis. Cell. 2007;130:691-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 852] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 57. | Beck B, Driessens G, Goossens S, Youssef KK, Kuchnio A, Caauwe A, Sotiropoulou PA, Loges S, Lapouge G, Candi A, Mascre G, Drogat B, Dekoninck S, Haigh JJ, Carmeliet P, Blanpain C. A vascular niche and a VEGF-Nrp1 loop regulate the initiation and stemness of skin tumours. Nature. 2011;478:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Fu CL, Zhao ZW, Zhang QN. The crosstalk between cellular survival pressures and N6-methyladenosine modification in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2025;24:67-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Fang T, Ma C, Yang B, Zhao M, Sun L, Zheng N. Roxadustat improves diabetic myocardial injury by upregulating HIF-1α/UCP2 against oxidative stress. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2025;24:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Dhamdhere SG, Bansal A, Singh P, Kakani P, Agrawal S, Samaiya A, Shukla S. Hypoxia-induced ATF3 escalates breast cancer invasion by increasing collagen deposition via P4HA1. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16:142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Du W, Xia X, Hu F, Yu J. Extracellular matrix remodeling in the tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1340634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Prakash J, Shaked Y. The Interplay between Extracellular Matrix Remodeling and Cancer Therapeutics. Cancer Discov. 2024;14:1375-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Zhao L, Zhang K, He H, Yang Y, Li W, Liu T, Li J. The Relationship Between Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Tumor Dormancy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:731393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Akabane M, Imaoka Y, Kawashima J, Endo Y, Schenk A, Sasaki K, Pawlik TM. Innovative Strategies for Liver Transplantation: The Role of Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Their Cell-Free Derivatives. Cells. 2024;13:1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Cortes-Dericks L, Galetta D. The therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells in lung cancer: benefits, risks and challenges. Cell Oncol (Dordr). 2019;42:727-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Neophytou CM, Kyriakou TC, Papageorgis P. Mechanisms of Metastatic Tumor Dormancy and Implications for Cancer Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:6158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Eltoukhy HS, Sinha G, Moore CA, Gergues M, Rameshwar P. Secretome within the bone marrow microenvironment: A basis for mesenchymal stem cell treatment and role in cancer dormancy. Biochimie. 2018;155:92-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Zhang HY, Zhu JJ, Liu ZM, Zhang YX, Chen JJ, Chen KD. A prognostic four-gene signature and a therapeutic strategy for hepatocellular carcinoma: Construction and analysis of a circRNA-mediated competing endogenous RNA network. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2024;23:272-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Ruff SM, Manne A, Cloyd JM, Dillhoff M, Ejaz A, Pawlik TM. Current Landscape of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:5863-5875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Shui L, Wu D, Yang K, Sun C, Li Q, Yin R. Bispecific antibodies: unleashing a new era in oncology treatment. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Montorfani J, Hatterer E, Chatel L, Lesnier A, Viandier A, Daubeuf B, Nouveau L, Malinge P, Calloud S, Masternak K, Ferlin W, Fischer N, Jandus C, Shang L. Selective activation of interleukin-2/interleukin-15 receptor signaling in tumor microenvironment using paired bispecific antibodies. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e010650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Liu WN, So WY, Harden SL, Fong SY, Wong MXY, Tan WWS, Tan SY, Ong JKL, Rajarethinam R, Liu M, Cheng JY, Suteja L, Yeong JPS, Iyer NG, Lim DW, Chen Q. Successful targeting of PD-1/PD-L1 with chimeric antigen receptor-natural killer cells and nivolumab in a humanized mouse cancer model. Sci Adv. 2022;8:eadd1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Dysthe M, Navin I, van Leeuwen D, Pineda J, Baumgartner C, Rooney CM, Parihar R. Constitutive IL-7 signaling promotes CAR-NK cell survival in the solid tumor microenvironment but impairs tumor control. J Immunother Cancer. 2025;13:e010672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Ingangi V, Minopoli M, Ragone C, Motti ML, Carriero MV. Role of Microenvironment on the Fate of Disseminating Cancer Stem Cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Krall JA, Reinhardt F, Mercury OA, Pattabiraman DR, Brooks MW, Dougan M, Lambert AW, Bierie B, Ploegh HL, Dougan SK, Weinberg RA. The systemic response to surgery triggers the outgrowth of distant immune-controlled tumors in mouse models of dormancy. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaan3464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 46.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Zeng Y, Pan Z, Yuan J, Song Y, Feng Z, Chen Z, Ye Z, Li Y, Bao Y, Ran Z, Li X, Ye H, Zhang K, Liu X, He Y. Inhibiting Osteolytic Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis by Bone-Targeted Nanoagent via Remodeling the Bone Tumor Microenvironment Combined with NIR-II Photothermal Therapy. Small. 2023;19:e2301003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ding J, Wang X, Wang F, Pan W, Li J, Wang S, Han Y. Hypoxia-amplifying polymer nanoprodrugs for sonodynamic chemotherapy for breast cancer and bone metastasis via in situ thrombogenesis. Mater Horiz. 2025;12:10793-10805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Liu X, Wang H, Li Z, Li J, He S, Hu C, Song Y, Gao H, Qin Y. Transformable self-delivered supramolecular nanomaterials combined with anti-PD-1 antibodies alleviate tumor immunosuppression to treat breast cancer with bone metastasis. J Nanobiotechnology. 2024;22:566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sinicrope FA, Turk MJ. Immune checkpoint blockade: timing is everything. J Immunother Cancer. 2024;12:e009722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/