Published online Jun 24, 2025. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v16.i6.104243

Revised: March 20, 2025

Accepted: May 7, 2025

Published online: June 24, 2025

Processing time: 188 Days and 3.5 Hours

Mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (MMR-D/MSI-H) colo

To determine the unique phenotypic characteristics of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs and leverage the conventional wisdom of LNY and LNR with the distinctive characteristics of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs.

This retrospective analysis involved 223 stage I-III CRC patients who underwent surgical resection without neoadjuvant treatment. Clinical and histological features were obtained from patient records and by re-examining the hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides. MMR/MSI status was evaluated for all patients using either MMR immunohistochemistry or MSI testing.

Of the 223 patients in our study, 87 (39.01%) were MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs while 136 (60.99%) were MMR-P/MSS CRCs. The MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs exhibited significant statistical differences compared to the MMR-P/MSS CRCs in several factors, including location, stage, tumor budding, lymphovascular and perineural invasion, lymphocytic response, LNY, LNR, and size of uninvolved lymph nodes. LNY and LNR were significantly higher in MMR-D/MSI-H group compared with the MMR-P/MSS group (P = 0.003 and P < 0.001, respectively). Also, the interquartile range of the largest uninvolved lymph node was 1 cm (0.8 cm-1.2 cm) in MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs compared to 0.7 cm (0.6 cm-0.97 cm) in MMR-P/MSS CRCs. The overall survival for the MMR-P/MSS CRC group was 71% at five years, and the MMR-D/MSI-H CRC group was 92% at five years (P < 0.001).

MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs possess a unique genomic profile that leads to distinct phenotypic characteristics, including an enhanced immune response. This distinctive profile underscores the substantial prognostic and predictive value of MMR-D/MSI-H status in CRC.

Core Tip: Mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (MMR-D/MSI-H) colorectal cancers (CRCs) account for 15% of CRCs exhibiting peculiar clinicopathological features. The correlation between MMR-D/MSI-H status and distinct lymph node characteristics, including increased lymph node yield, low lymph node ratio, and larger uninvolved node size, suggests a potential link to the heightened immune response typical of these cancers. These findings reinforce the promising prognosis associated with MMR-D/MSI-H CRC, reflecting improved overall survival rates compared to mismatch repair proficient or microsatellite stable tumors and offering valuable insights for tailored therapeutic approaches in this specific subtype of CRC.

- Citation: Mehta A, Bansal D, Tripathi R, Anoop V. Phenotypic attributes and survival in mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high colorectal carcinomas. World J Clin Oncol 2025; 16(6): 104243

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v16/i6/104243.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v16.i6.104243

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, affecting approximately 1.9 million individuals each year[1]. While about 70% of cases are sporadic, the remaining 30% have a hereditary component, with approximately 15% categorized as mismatch repair deficient (MMR-D) or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H)[2,3]. Recently, there has been an upsurge of interest in this distinct subtype of CRC due to its unique genomic and im

The highly conserved DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system serves as a cellular proofreader, meticulously correcting errors that arise during DNA replication and recombination. This intricate machinery consists of four essential proteins that work in a coordinated manner: MutL homolog 1, MutS homolog (MSH) 2, MSH6, and postmeiotic segregation increased 2[3]. Failure of this system, termed MMR-D, manifests as microsatellite instability (MSI), characterized by insertions or deletions within repetitive DNA sequences known as microsatellites[3].

MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs have a unique genomic landscape, translating into a spectrum of distinct phenotypic attributes that set them apart from their microsatellite stable (MSS) counterparts[4-6]. This particular signature leads to an increased immune response characterized by abundant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), often accompanied by unusual histopathological features like medullary, mucinous adenocarcinoma or signet-ring cell carcinoma[4-6]. Additionally, MMR-D/MSI-H tumor exhibits a significantly higher mutational burden, which increases the potential for generating highly immunogenic neoantigen(s) and a robust response to treatment interventions[7].

MMR-D/MSI-H status holds immense prognostic and predictive value in CRC[6,8]. Patients harboring these tumors have better overall and disease-specific survival compared to those with MSS tumors[6]. Their pronounced immunogenicity translates into a limited benefit from 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant chemotherapy, rendering them prime candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy[7-9]. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved pembrolizumab for patients with advanced/metastatic MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, underscoring its clinical importance[8,9]. Furthermore, identifying MMR-D/MSI-H tumors prompts further genetic testing for Lynch syndrome, which can start cascade screening and help detect many healthy and predisposed carriers[10].

Traditionally, CRC prognostication relies on factors like tumor stage, differentiation, tumor budding, lymphovascular invasion, perineural invasion (PNI), and lymph node involvement[11]. Recently, lymph node yield (LNY) and lymph node ratio (LNR) have emerged as essential prognostic parameters[12-16]. The relationship between the immunogenic characteristics of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs and lymph node retrieval and size remains underexplored, despite its potential clinical significance[17-19]. In this study, we aimed to investigate this relatively unexplored area, applying the concepts of LNY and LNR to assess how the unique features of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs influence lymph node dynamics. This is the first study to evaluate and compare the histopathological features, lymph node dynamics, and their correlation with overall survival between MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs and mismatch repair proficient (MMR-P)/MSS CRCs.

This was a retrospective study of 223 consecutive CRC patients who underwent resection at a tertiary care cancer institute from January 1, 2015 to December 31, 2021. Clinico-radiological details were collected from the electronic medical records (EMR), and follow-up data were obtained through EMR or telephone.

The institutional review board approved all procedures performed in the current study (No. Res/SCM/49/2021/160 dated August 3, 2022) according to the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments and granted a waiver from consent.

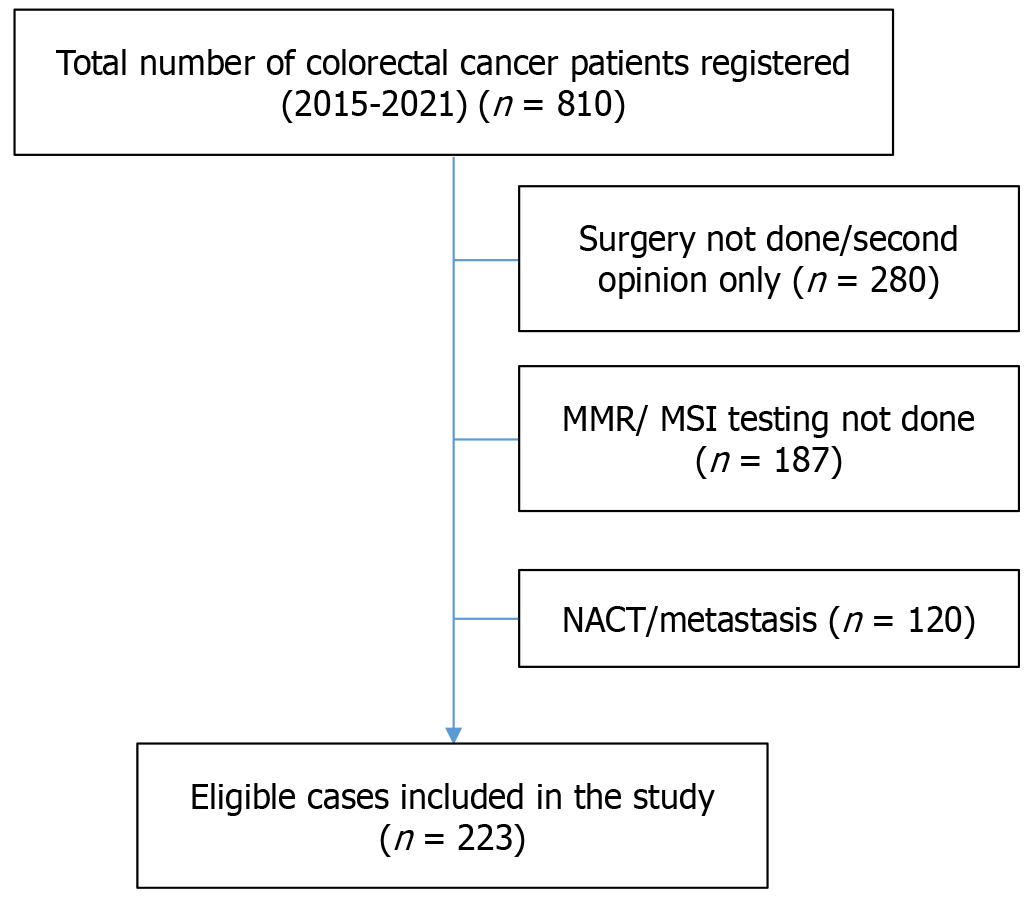

The study excluded cases of CRCs that did not undergo surgical resection, receive neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or present with metastasis at the time of diagnosis. Stage IV CRCs were particularly excluded from the analysis because either they had a small biopsy sample that was insufficient to study the histopathological characteristics related to MMR, they had already received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or they had metastasis at the time of presentation. The CRCs in which MMR/MSI testing was not done were also excluded.

Information regarding age, sex, and location [right-sided (caecum, ascending colon, transverse colon) and left-sided (descending colon, sigmoid colon, rectum)] was recorded for all patients. Two experienced pathologists (Mehta A and Bansal D) jointly re-evaluated all hematoxylin and eosin slides of CRC specimens to identify morphological subtypes (conventional, mucinous, signet ring cell and others), histologic grades (well, moderate or poor; as per American Joint Committee on Cancer grading system, 8th edition of the tumor-node-metastasis manual)[20], the percentage of the mucinous component (less than or greater than 50%), tumor budding (classified as low, intermediate or high based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference 2016 guidelines)[21], and the presence of lymphovascular and PNI.

The lymphocytic response was evaluated: Peritumoral lymphocytic reaction (PLR) and intraepithelial TILs (IETILS). PLR, also known as Crohn’s disease-like reaction, refers to the lymphoid aggregates in the muscularis propria or pericolic fatty tissue, located one or more millimeters beyond the advancing edges of the tumor. PLR was graded based on the percentage of lymphoid aggregates: < 10%, 10%-25%, 25%-50%, > 50%. IETILS were graded as none (no lymphocytes), mild to moderate (1 or 2 lymphocytes per high-power field), or marked (3 or more lymphocytes per high-power field) according to the cancer reporting protocol released by the College of American Pathologists[22]. Pathological staging was conducted according to the 8th edition of the tumor-node-metastasis guidelines established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer[20]. LNY was determined by counting the total number of lymph nodes retrieved from the resected specimen. LNR was calculated as the ratio of metastatic nodes to the total number of lymph nodes isolated. These values and the size of the largest uninvolved lymph node (in cm) were extracted from the pathology reports within the EMR.

The expression of MMR proteins using immunohistochemistry for MutL homolog 1 [clone M1, ready-to-use (RTU); Ventana], MSH2 (clone G219-1129, RTU; Ventana), MSH6 (clone SP93, RTU; Ventana), and postmeiotic segregation increased 2 (A16-4, RTU; Ventana) was studied on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tumor tissues. All the stains were performed using an automated instrument (Ventana Benchmark Ultra) following the manufacturer’s instructions. For the analysis of the immunoreactivity, only the complete absence of nuclear staining in all the tumor cells was considered as negative expression (loss of MMR protein: MMR-D) and was considered positive by the presence of intact nuclear staining within the tumor, regardless of its intensity or the number of positive nuclei (intact MMR protein: MMR-P). Adjacent normal control tissue, stromal tissue, or lymphocytes were taken as an internal positive control.

Samples from a tumor specimen and normal tissue were tested for MSI using fragment length analysis. All the cases tested for MMR protein immunohistochemistry also underwent MSI testing. Briefly, five microsatellite loci, BAT-25, BAT-26, MONO-27, NR-21, and NR-24, were amplified and sized by capillary electrophoresis resolution using an Applied Biosystems SeqStudio Genetic Analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States). The procedure details are per the Promega MSI analysis system (Promega Corporation, United States). Instability in one locus is termed MSI-low, and instability in ≥ 2 loci is termed MSI-H.

Statistical analysis was done using statistical product and service solutions (SPSS) version 23 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, United States). Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, whichever was appropriate, was used for categorical variables. Survival analysis was done using the Kaplan-Meier method. A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Two hundred twenty-three patients with CRC were considered eligible based on our exclusion criteria and hence included in the study. The consort diagram of the patients included in the study is shown in Figure 1. Of the 223 patients in our research, 87 (39.01%) were MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, while 136 (60.99%) were MMR-P/MSS CRCs. The relevant clinical and histopathological features of the included patients in our study are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 223) | MMR-D/MSI-H (n = 87) (39.01%) | MMR-P/MSS (n = 136) (60.99%) | P value |

| Age | 0.207 | |||

| ≤ 40 years | 35 (15.7) | 17 (19.5) | 18 (13.2) | |

| > 40 years | 188 (84.3) | 70 (80.5) | 118 (86.8) | |

| Sex | 0.243 | |||

| Male | 146 (65.5) | 61 (70.1) | 85 (62.5) | |

| Female | 77 (34.5) | 26 (29.9) | 51 (37.5) | |

| Location | < 0.001 | |||

| Right | 130 (58.3) | 69 (79.3) | 61 (44.9) | |

| Left | 93 (41.7) | 18 (20.7) | 75 (55.1) | |

| Stage | < 0.001 | |||

| I | 14 (6.2) | 6 (6.9) | 8 (5.9) | |

| II | 126 (56.5) | 67 (77) | 59 (43.4) | |

| III | 83 (37.2) | 14 (16.1) | 69 (50.7) | |

| Overall survival at five years | - | 92% | 71% | < 0.001 |

| Characteristics | Total (n = 223) | MMR-D/MSI-H (n = 87) (39.01%) | MMR-P/MSS (n = 136) (60.99%) | P value |

| Morphology | 0.092 | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 181 (81.1) | 72 (82.8) | 109 (80.1) | |

| Mucinous adenocarcinoma | 26 (11.7) | 13 (14.9) | 13 (9.6) | |

| Signet ring carcinoma | 12 (5.4) | 1 (1.1) | 11 (8.1) | |

| Others | 4 (1.8) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (2.2) | |

| Grade | 0.708 | |||

| Well-differentiated | 2 (0.9) | 1 (1.1) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Moderately differentiated | 167 (74.9) | 63 (72.4) | 105 (77.2) | |

| Poorly differentiated | 53 (23.8) | 23 (26.4) | 30 (22.1) | |

| Mucinous component | 0.078 | |||

| ≤ 50% | 204 (91.5) | 76 (87.4) | 128 (94.1) | |

| > 50% | 19 (8.5) | 11 (12.6) | 8 (5.9) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | < 0.001 | |||

| Absent | 131 (58.7) | 66 (75.9) | 65 (47.8) | |

| Present | 92 (41.3) | 21 (24.1) | 71 (52.2) | |

| Perineural invasion | < 0.001 | |||

| Absent | 188 (84.3) | 83 (95.4) | 105 (77.2) | |

| Present | 35 (15.7) | 4 (4.6) | 31 (22.8) | |

| Tumor budding | < 0.001 | |||

| Low | 76 (38.2) | 43 (52.4) | 33 (28.2) | |

| Intermediate | 26 (13.1) | 12 (14.6) | 14 (12) | |

| High | 97 (48.7) | 27 (32.9) | 70 (59.8) | |

| Intraepithelial lymphocytes | < 0.001 | |||

| None | 113 (50.7) | 19 (21.8) | 94 (69.1) | |

| Mild-moderate | 42 (18.8) | 17 (19.5) | 25 (18.4) | |

| Marked | 68 (30.5) | 51 (58.6) | 17 (12.5) | |

| Peritumoral lymphocytes | < 0.001 | |||

| < 10% | 89 (39.9) | 21 (24.1) | 68 (50) | |

| 10%-25% | 96 (43) | 43 (49.4) | 53 (39) | |

| 25%-50% | 31 (13.9) | 17 (19.5) | 14 (10.3) | |

| > 50% | 7 (3.1) | 6 (6.9) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Lymph node yield, mean ± SD | 25.96 ± 11.6 | 28.90 ± 12.80 | 23.95 ± 10.30 | < 0.0001 |

| Lymph node ratio, mean ± SD | 0.09 ± 0.19 | 0.02 ± 0.05 | 0.14 ± 0.23 | < 0.001 |

Of the total 223 CRC patients included in the study, 188 (84.3%) were more than 40 years of age. The mean age of MMR-D/MSI-H CRC patients was 52 years, and that of MMR-P/MSS CRC patients was 56 years. The male/female ratio was 1.9:1 for all CRC patients. There was no statistically significant age and sex predilection between MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS groups. The location of cancer in the colon was right-sided in 130 (58.3%) and left-sided in 93 (41.7%) patients. MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs were predominantly located on the right side of the colon (79.3%), while MMR-P/MSS CRCs were predominantly located on the left side of the colon (55.1%) (P < 0.001).

Of all the CRC patients, 126 (56.5%) presented with stage II disease and 83 (37.2%) had stage III disease. Most of the MMR-D/MSI-H patients had stage II disease (77%) followed by stage III (16.1%), while 69 (50.7%) of MMR-P/MSS patients had predominantly stage III disease followed by stage II (n = 59, 43.4%). The statistical analysis showed that the stage at presentation was lower in the MMR-D/MSI-H group than in the MMR-P/MSS group (P < 0.001).

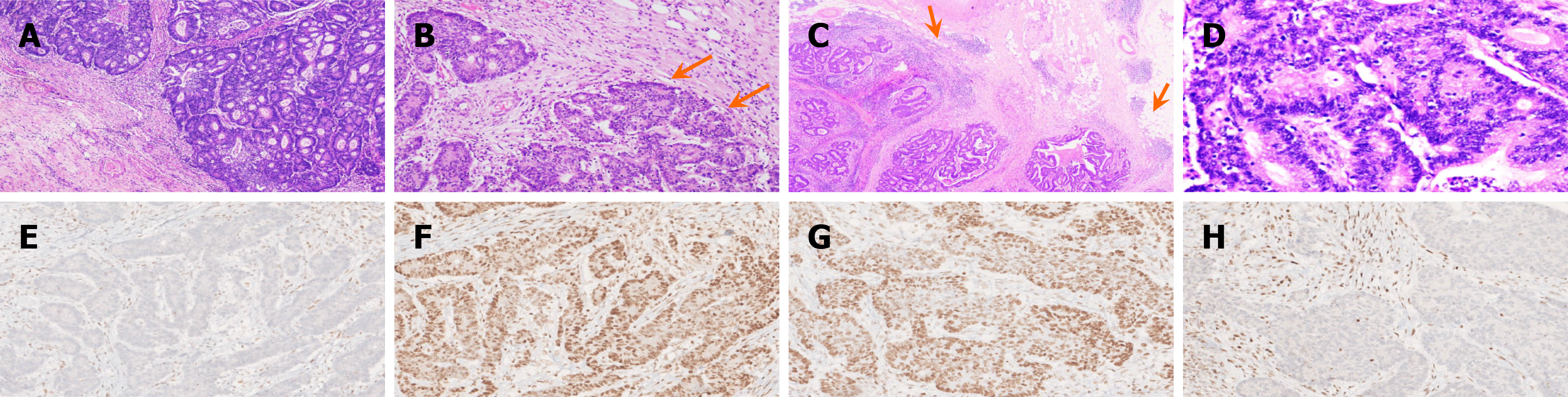

The histopathological features of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs are shown in Figure 2A-H. The tumor histologic type of CRCs was adenocarcinoma in 181 (81.1%) patients, followed by mucinous adenocarcinoma in 26 (11.7%) patients, and other histologic types were seen in 16 (7.2%) patients. Adenocarcinoma was most common in MMR-D/MSI-H (82.8%) and MMR-P/MSS patients (80.1%). The most common grade of CRCs in overall patients, MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS group, was moderately differentiated (G2) (74.9%, 72.4%, 77.2%, respectively), followed by poorly differentiated (23.8%, 26.4%, 22.1%, respectively) (Figure 2A). There was no statistical difference in tumor histologic type (including mucinous component) and grading between MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS CRC patients (P = 0.092, P = 0.708, respectively), as shown in Table 2.

The tumor budding was evaluated in 199 out of 223 CRC patients. The tumor budding was high in 97 (43.5%) of the 199 evaluated CRC patients but predominantly low in the MMR-D/MSI-H group (n = 43, 52.4%). Low tumor budding in MMR-D/MSI-H patients (Figure 2B) was statistically significant (P < 0.001) when compared with the MMR-P/MSS group, as shown in Table 2. A similar statistically significant difference (P < 0.001) was seen with lymphovascular and PNI in MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS groups. Lymphovascular and PNI was seen frequently in the MMR-P/MSS group compared to the MMR-D/MSI-H group (52.2% vs 24.1%, 22.8 % vs 4.6%, respectively), as shown in Table 2.

Lymphocytic infiltration was assessed in PLR (Figure 2C) and IETILS (Figure 2D). The MMR-P/MSS group had < 10% PLR in 68 (50%) patients, while the MMR-D/MSI-H group had 10%-25% PLR in 96 (49.4%) patients. Similarly, IETILS was marked in 51(58.6%) MMR-D/MSI-H patients, while only 17 (12.5%) MMR-P/MSS patients had marked IETILS. The contrast in lymphocytic infiltration, observed through PLR or IETILS, showed statistical significance when comparing the MMR-D/MSI-H group with the MMR-P/MSS group (P < 0.001) (Table 2).

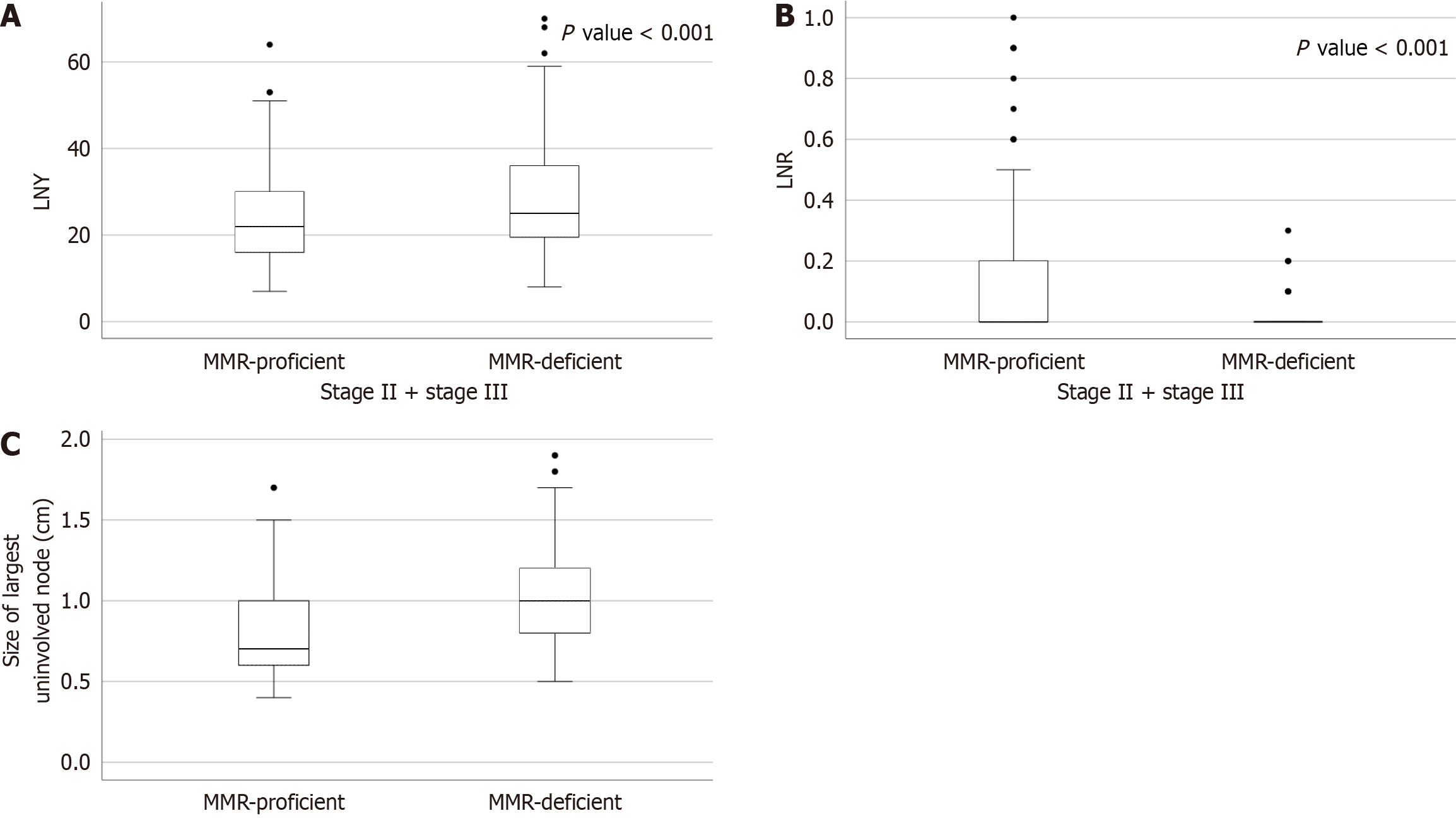

Their mean values were observed concerning the MMR status to ascertain the importance of LNY and LNR in CRC. The mean ± SD values of LNY and LNR were 28.90 ± 12.80 and 0.020 ± 0.05 in MMR-D/MSI-H as compared to 23.95 ± 10.3 and 0.14 ± 0.23 in MMR-P/MSS CRCs, respectively. LNY varied among the patients and was not greater than 12 in all cases. LNY and LNR were significantly higher in MMR-D/MSI-H group compared with the MMR-P/MSS group (P = 0.003 and P < 0.001, respectively) (Table 2). The difference in the LNY and LNR was statistically significant between MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS groups when compared for combined stage II and stage III CRCs (P < 0.001) (Figure 3A and B). Also, the interquartile range of the largest uninvolved lymph node was 1 cm (0.8 cm-1.2 cm) in MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs compared to 0.7 cm (0.6 cm-0.97 cm) in MMR-P/MSS CRCs (Figure 3C).

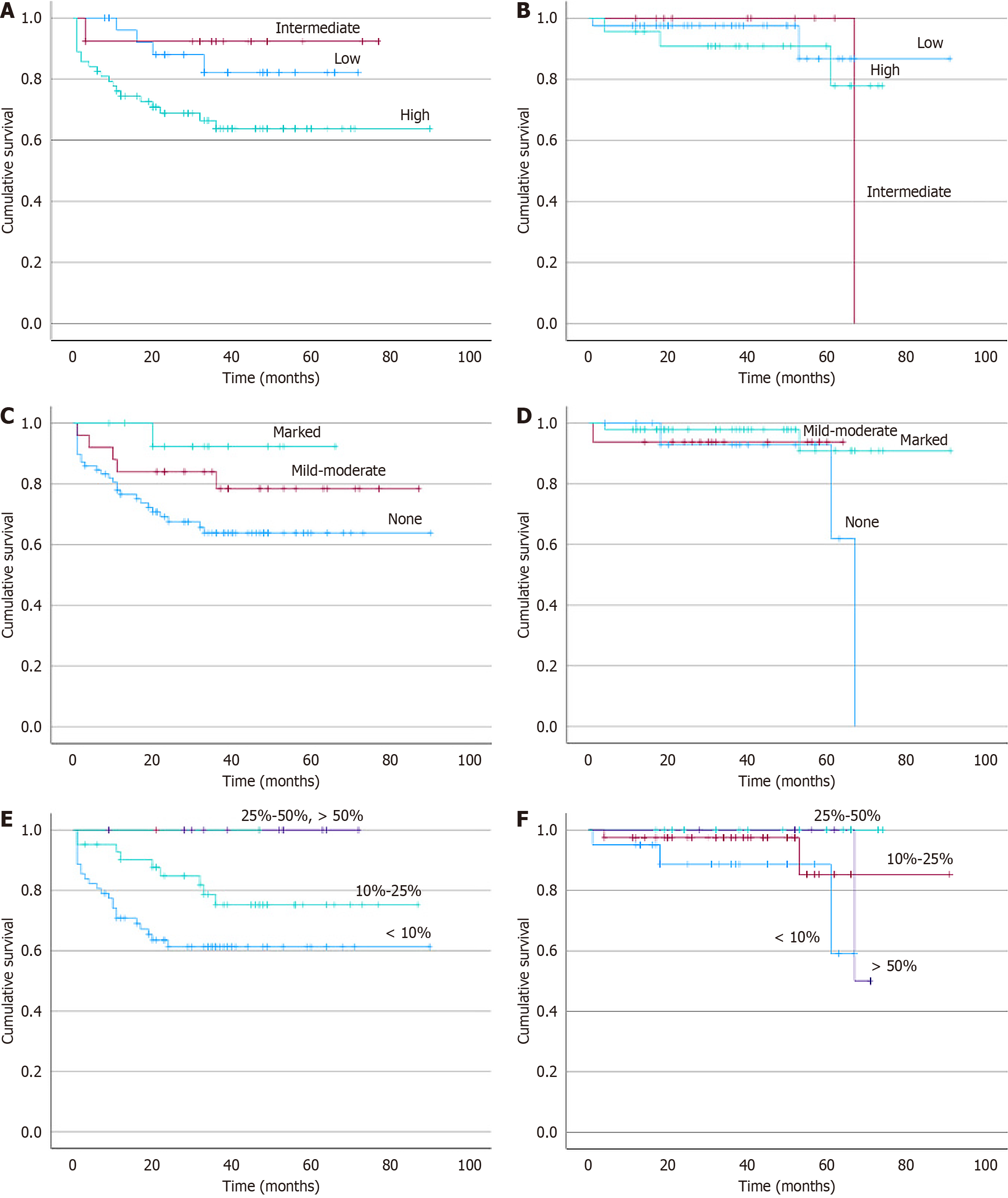

The median follow-up duration was 33 months. Total of 223 CRC patients, 160 (71.7%) were alive, 38 (17%) were dead, and 25 (11.2%) were lost to follow-up. The overall survival for the MMR-P/MSS CRC group was 71% at five years, and the MMR-D/MSI-H CRC group was 92% at five years (P < 0.001). The overall survival of all patients concerning tumor budding, IETILs, and PLR has been shown in Figure 4.

While most CRCs progress through the chromosomal instability pathway, approximately 15% show MSI due to impaired MMR mechanisms[3]. The rate of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs at our institute is 18.9% when evaluated for all the CRC cases that have undergone MMR/MSI testing. However, in this study, we observed a higher rate of 39.01% for MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs amongst the selected CRC patients. This increase in MMR-D/MSI-H cases can be attributed to excluding a substantial number of cases, particularly those in the rectum, which tend to present at advanced stages requiring preoperative treatment and mainly exhibit MMR-P/MSS status. Additionally, patients with metastatic disease were excluded from the study at the time of presentation.

Prior studies show that MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs are frequently reported in the younger age group[4,5]. However, our study did not identify any statistically significant age difference between the MMR-D/MSI-Hand MMR-P/MSS /MSS/MSS CRC groups. Similarly, literature has suggested a female sex predilection for MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs[4,5,19]; however, we did not find any such preponderance within our study group. The variations in the results could be due to the study’s limited sample size and the exclusion of many cases based on predefined exclusion criteria. MMR-D/MSI-H CRC group of our study displayed a preference for the right side of the colon (P < 0.001), aligning with the findings from previous research in the literature[4,5,19].

The majority of the patients of MMR-D/MSI-H CRC were diagnosed at stage II, with stage III being the next most common stage. In contrast, patients in the MMR-P/MSS group predominantly presented with stage III disease, followed by stage II. These stage distribution patterns were consistent with previous studies[4,5,19] and provided insights into our study’s differing clinical profiles of MMR-D/MSI-H and MMR-P/MSS CRC patients. MMR-P/MSS CRCs often exhibit a higher frequency of chromosomal instability. They are more likely to present at advanced stages, such as stages III/IV, compared to MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, which usually present at earlier stages, such as stages I/II, thus indicating a good prognosis.

MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs show no differences in histopathological features compared to MMR-P/MSS CRCs[4,5,11-16,19]. These distinctions are crucial in the diagnosis and prognosis of CRC subtypes. Unsurprisingly, MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs were mainly of the adenocarcinoma histologic subtype, followed by the mucinous subtype. However, the grading was predominantly moderately differentiated (G2) in our study, in contrast to poorly differentiated (G3) histology demonstrated by Liang et al[4] and others[5,19]. Furthermore, MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs exhibited low tumor budding and lower lymphovascular invasion and PNI rates than MMR-P/MSS CRCs (P < 0.001), thus imparting a good prognosis. While our study did not find a predisposition for poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with medullary features in MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, it did reveal low tumor budding, consistent with earlier research findings[23].

In line with previous research[24,25] our study similarly highlighted immune solid cell infiltration, influencing anti-tumor immunity, as one of the contributing factors to the favorable prognosis of MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs. In a study by Williams et al[25], patients with TIL-high and MMR-D/MSI-H tumors, comprising approximately 15% of cases, displayed the most favorable prognosis. In contrast, patients with TIL-low and MMR-D/MSI-H tumors showed a poorer disease-free survival (DFS) rate, akin to those with TIL-low and MMR-P tumors, collectively accounting for approximately 70% of cases[25]. Patients with TIL-high and MMR-P/MSS tumors demonstrated an intermediate DFS rate[25]. Our study found that PLR and IETILS had statistically significant differences between MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs and MMR-P/MSS CRCs (P < 0.001).

Several factors influence the quantity of harvested lymph nodes. Specifically, LNY tends to be higher in right-sided colon neoplasms, larger tumors, poorly differentiated morphology, significant inflammatory infiltrate, and MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs. In MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, the generation of frameshift mutations within coding microsatellites forms neoantigens[26]. This triggers the immune system, leading to a significantly robust lymphocytic infiltration, a distinctive hallmark of this cancer type[27]. This heightened immune response increases the number of TILs within the primary tumor and surrounding lymph nodes. The draining lymph nodes show hyperplastic changes, leading to more significant and more detectable lymph nodes during surgical resection and higher LNY[28]. In MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, this elevated immune response may contribute to better control of tumor growth and a lower likelihood of lymph node metastasis, hence, low LNR.

Our study also observed similar findings with the MMR-D/MSI-H CRC group, leading to a larger uninvolved lymph node, higher LNY, and lower LNR than the MMR-P/MSS CRC group. In a study by Zannier et al[19] on 1037 CRC cases, a higher LNY and a lower LNR were observed in MMR-D/MSI CRC neoplasms than in MMR-P CRC neoplasms (P < 0.001)[19]. They also suggested the role of prominent antitumor reactions leading to hyperplastic lymph nodes[19]. However, Arnold et al[18] counter the notion that MSI-driven mechanisms solely dictate LNY in CRC, proposing a significant variance in LNY between the proximal and distal colon as a factor[18].

Numerous studies have substantiated the prognostic significance of LNY and LNR in CRCs[12-16]. A higher LNY and low LNR are associated with a good prognosis[12-16]. Belt et al[17] studied the association between LNY, MSI status, and recurrence rate in colon cancer. Tumors exhibiting a high LNY are notably associated with the MSI phenotype (high LNY: 26.3%, MSI tumors vs low LNY: 15.1%, MSI tumors; P = 0.01), mainly in stage III tumors. MSI tumors with high LNY had a better DFS when compared to MSI tumors with low LNY[17]. Hence, the lymph node size can be considered a semi-quantitative parameter reflecting the local immune response, potentially linking increased LNY and improved survival benefits.

A statistically significant difference was also observed when we compared LNY and LNR of stage II and III MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs with the MMR-P/MSS CRC group, suggesting an association with good prognosis. In our study, the MMR-D/MSI-H CRC group showed a lower stage at presentation when compared to the MMR-P/MSS CRC group and, thus, better overall survival. This overall good prognosis of the MMR-D/MSI-H group can be attributed to heightened immune responses, leading to increased lymphocytic infiltration within the tumor and better control of tumor growth with less metastasis.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective nature, due to which inherent biases may be present. The Food and Drug Administration has approved pembrolizumab for patients with advanced/metastatic MMR-D/MSI-H CRCs, emphasizing its clinical significance. More recently, dostarlimab, an anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 antibody, has demonstrated remarkable efficacy, achieving a 100% remission rate in adults with MMR-D recurrent or advanced CRCs[29]. Additionally, adjuvant immunotherapy has shown significant survival benefits in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer[30]. These findings suggest a promising potential for extrapolating similar immunotherapeutic strategies to early-stage CRC.

Our findings underscore the promising prognosis associated with MMR-D/MSI-H CRC and provide valuable insights for tailoring therapeutic approaches to this specific subgroup of CRCs. The high immune infiltration and mutational burden of MMR-D/MSI-H tumors make them ideal candidates for immunotherapy, with durable responses observed in some patients. However, resistance to immunotherapy can occur due to factors like intratumoral heterogeneity and immune evasion mechanisms. Ongoing research aims to elucidate further the complex interplay between MMR-D/MSI-H status, the tumor immune microenvironment, and therapeutic response to optimize treatment strategies for this CRC subtype.

| 1. | Xi Y, Xu P. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Transl Oncol. 2021;14:101174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 687] [Cited by in RCA: 1586] [Article Influence: 317.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Mármol I, Sánchez-de-Diego C, Pradilla Dieste A, Cerrada E, Rodriguez Yoldi MJ. Colorectal Carcinoma: A General Overview and Future Perspectives in Colorectal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 968] [Article Influence: 107.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Fassan M, Scarpa A, Remo A, De Maglio G, Troncone G, Marchetti A, Doglioni C, Ingravallo G, Perrone G, Parente P, Luchini C, Mastracci L. Current prognostic and predictive biomarkers for gastrointestinal tumors in clinical practice. Pathologica. 2020;112:248-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liang Y, Cai X, Zheng X, Yin H. Analysis of the Clinicopathological Characteristics of Stage I-III Colorectal Cancer Patients Deficient in Mismatch Repair Proteins. Onco Targets Ther. 2021;14:2203-2212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Viñal D, Martinez-perez D, Martínez-recio S, Ruiz I, Jiménez Bou D, Peña J, Martin-montalvo G, Rueda-lara A, Alameda M, Gutiérrez Sainz L, Custodio AB, Palacios ME, Ghanem I, Rodriguez Salas N, Feliu J. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcomes of patients with deficient mismatch repair colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:181-181. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Popat S, Hubner R, Houlston RS. Systematic review of microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:609-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1365] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Sahin IH, Akce M, Alese O, Shaib W, Lesinski GB, El-Rayes B, Wu C. Immune checkpoint inhibitors for the treatment of MSI-H/MMR-D colorectal cancer and a perspective on resistance mechanisms. Br J Cancer. 2019;121:809-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 41.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | André T, Shiu KK, Kim TW, Jensen BV, Jensen LH, Punt C, Smith D, Garcia-Carbonero R, Benavides M, Gibbs P, de la Fouchardiere C, Rivera F, Elez E, Bendell J, Le DT, Yoshino T, Van Cutsem E, Yang P, Farooqui MZH, Marinello P, Diaz LA Jr; KEYNOTE-177 Investigators. Pembrolizumab in Microsatellite-Instability-High Advanced Colorectal Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2207-2218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 962] [Cited by in RCA: 2063] [Article Influence: 343.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sargent DJ, Marsoni S, Monges G, Thibodeau SN, Labianca R, Hamilton SR, French AJ, Kabat B, Foster NR, Torri V, Ribic C, Grothey A, Moore M, Zaniboni A, Seitz JF, Sinicrope F, Gallinger S. Defective mismatch repair as a predictive marker for lack of efficacy of fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy in colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3219-3226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1132] [Cited by in RCA: 1244] [Article Influence: 77.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Umar A, Boland CR, Terdiman JP, Syngal S, de la Chapelle A, Rüschoff J, Fishel R, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Hamelin R, Hamilton SR, Hiatt RA, Jass J, Lindblom A, Lynch HT, Peltomaki P, Ramsey SD, Rodriguez-Bigas MA, Vasen HF, Hawk ET, Barrett JC, Freedman AN, Srivastava S. Revised Bethesda Guidelines for hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (Lynch syndrome) and microsatellite instability. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2154] [Cited by in RCA: 2270] [Article Influence: 103.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Washington MK, Goldberg RM, Chang GJ, Limburg P, Lam AK, Salto-Tellez M, Arends MJ, Nagtegaal ID, Klimstra DS, Rugge M, Schirmacher P, Lazar AJ, Odze RD, Carneiro F, Fukayama M, Cree IA; WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. Diagnosis of digestive system tumours. Int J Cancer. 2021;148:1040-1050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee CHA, Wilkins S, Oliva K, Staples MP, McMurrick PJ. Role of lymph node yield and lymph node ratio in predicting outcomes in non-metastatic colorectal cancer. BJS Open. 2019;3:95-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Betge J, Harbaum L, Pollheimer MJ, Lindtner RA, Kornprat P, Ebert MP, Langner C. Lymph node retrieval in colorectal cancer: determining factors and prognostic significance. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32:991-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ceelen W, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Pattyn P. Prognostic value of the lymph node ratio in stage III colorectal cancer: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:2847-2855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Rosenberg R, Friederichs J, Schuster T, Gertler R, Maak M, Becker K, Grebner A, Ulm K, Höfler H, Nekarda H, Siewert JR. Prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer is associated with lymph node ratio: a single-center analysis of 3,026 patients over a 25-year time period. Ann Surg. 2008;248:968-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang CH, Li YY, Zhang QW, Biondi A, Fico V, Persiani R, Ni XC, Luo M. The Prognostic Impact of the Metastatic Lymph Nodes Ratio in Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2018;8:628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Belt EJ, te Velde EA, Krijgsman O, Brosens RP, Tijssen M, van Essen HF, Stockmann HB, Bril H, Carvalho B, Ylstra B, Bonjer HJ, Meijer GA. High lymph node yield is related to microsatellite instability in colon cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1222-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arnold A, Kloor M, Jansen L, Chang-Claude J, Brenner H, von Winterfeld M, Hoffmeister M, Bläker H. The association between microsatellite instability and lymph node count in colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2017;471:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zannier F, Angerilli V, Spolverato G, Brignola S, Sandonà D, Balistreri M, Sabbadin M, Lonardi S, Bergamo F, Mescoli C, Scarpa M, Bao QR, Dei Tos AP, Pucciarelli S, Urso ELD, Fassan M. Impact of DNA mismatch repair proteins deficiency on number and ratio of lymph nodal metastases in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;243:154366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Amin MB, Gress DM, Meyer Vega, Edge SB. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York: Springer, 2018. |

| 21. | Lugli A, Kirsch R, Ajioka Y, Bosman F, Cathomas G, Dawson H, El Zimaity H, Fléjou JF, Hansen TP, Hartmann A, Kakar S, Langner C, Nagtegaal I, Puppa G, Riddell R, Ristimäki A, Sheahan K, Smyrk T, Sugihara K, Terris B, Ueno H, Vieth M, Zlobec I, Quirke P. Recommendations for reporting tumor budding in colorectal cancer based on the International Tumor Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016. Mod Pathol. 2017;30:1299-1311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 575] [Cited by in RCA: 798] [Article Influence: 88.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | College of American Pathologists. Cancer Protocol Templates. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with primary carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Jun, 2017. [cited 24 October 2024]. Available from: extension://ngbkcglbmlglgldjfcnhaijeecaccgfi/https://documents.cap.org/protocols/cp-gilower-colonrectum-17protocol-4010.pdf. |

| 23. | Ryan É, Khaw YL, Creavin B, Geraghty R, Ryan EJ, Gibbons D, Hanly A, Martin ST, O'Connell PR, Winter DC, Sheahan K. Tumor Budding and PDC Grade Are Stage Independent Predictors of Clinical Outcome in Mismatch Repair Deficient Colorectal Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol. 2018;42:60-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mei Z, Liu Y, Liu C, Cui A, Liang Z, Wang G, Peng H, Cui L, Li C. Tumour-infiltrating inflammation and prognosis in colorectal cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2014;110:1595-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 244] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Williams DS, Mouradov D, Jorissen RN, Newman MR, Amini E, Nickless DK, Teague JA, Fang CG, Palmieri M, Parsons MJ, Sakthianandeswaren A, Li S, Ward RL, Hawkins NJ, Faragher I, Jones IT, Gibbs P, Sieber OM. Lymphocytic response to tumour and deficient DNA mismatch repair identify subtypes of stage II/III colorectal cancer associated with patient outcomes. Gut. 2019;68:465-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schwitalle Y, Kloor M, Eiermann S, Linnebacher M, Kienle P, Knaebel HP, Tariverdian M, Benner A, von Knebel Doeberitz M. Immune response against frameshift-induced neopeptides in HNPCC patients and healthy HNPCC mutation carriers. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:988-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 260] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Dolcetti R, Viel A, Doglioni C, Russo A, Guidoboni M, Capozzi E, Vecchiato N, Macrì E, Fornasarig M, Boiocchi M. High prevalence of activated intraepithelial cytotoxic T lymphocytes and increased neoplastic cell apoptosis in colorectal carcinomas with microsatellite instability. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1805-1813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Murphy J, Pocard M, Jass JR, O'Sullivan GC, Lee G, Talbot IC. Number and size of lymph nodes recovered from dukes B rectal cancers: correlation with prognosis and histologic antitumor immune response. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1526-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shuvo PA, Tahsin A, Rahman MM, Emran TB. Dostarlimab: The miracle drug for the treatment of colorectal cancer. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;81:104493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tang WF, Ye HY, Tang X, Su JW, Xu KM, Zhong WZ, Liang Y. Adjuvant immunotherapy in early-stage resectable non-small cell lung cancer: A new milestone. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1063183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/