INTRODUCTION

Primary liver cancer, also known as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), originates in the liver and is often associated with chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis, infections with hepatitis B or C viruses, or alcohol-related liver disease[1]. Conversely, metastatic liver cancer refers to tumors formed outside the liver that metastasize to the liver and colonize it. Owing to the dual blood supply from the hepatic artery and portal vein, the liver has become the most common parenchymal organ to which most malignant tumors metastasize[2]. Metastatic cancer has become a major clinical challenge because of its high incidence and poor prognosis. Metastatic liver cancer, or liver metastasis, is caused by the spread of cancer cells from other primary sites (such as the colon, rectum, stomach, and breast) to the live[3-6]. The prognosis of patients with liver metastasis varies depending on the type of primary cancer. Liver metastasis in some cancers, such as lung cancer, is associated with a poor prognosis[7].

Currently, the treatment of metastatic liver cancer is completely different from that of the primary cancer. Although tumors grow in the liver, the biological activity of metastatic liver cancer is different from that of tumors at the primary site, and liver metastasis has the characteristics of multifocal and late-stage diseases[7]. The treatment of metastatic liver cancer usually involves systemic treatments such as chemotherapy and targeted therapy[3-6]. Therefore, initially determining the organ or tissue source of the primary cancer is necessary (to obtain pathology findings) and then use systemic treatment (choosing a plan based on the pathology of the primary cancer) and local liver resection, including surgical, ablation, and systemic treatment methods[7-10]. The combination of minimally invasive image-guided therapies, such as radioembolization and percutaneous liver-guided therapy, has expanded the treatment options for patients with obvious metastatic liver disease. However, further research is required to optimize the timing and safety of combining systemic and local regional therapies. Metastatic liver cancer presents a complex clinical environment with different primary cancer origins, prognostic impacts, and challenges in accurate diagnosis and management. Understanding the metastatic patterns, prognostic factors, and immune microenvironments of liver metastases is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies and improving patient prognosis[11-13].

Abnormal alternative splicing (AS) is a molecular characteristic unique to almost all tumor types[14]. Most tumors exhibit a wide range of splicing abnormalities compared to the surrounding healthy tissues, including frequent retention of normally excised introns, inappropriate expression of isoforms that are typically limited to other cell types or developmental stages, splicing errors that damage tumor suppressor genes or promote oncogenic gene expression, and promotion of tumor development through various mechanisms, including increased cell proliferation, reduced apoptosis, enhanced migration and metastasis, drug-resistant chemotherapy, and evasion of immune monitoring[15,16]. Metastatic liver cancer undergoes significant changes over time. In cancer cells derived from the liver and bile ducts, abnormal proteins are synthesized due to abnormal splicing associated with cancer. This leads to the dysproliferation of these cells, ultimately transforming them into invasive, migratory, and multidrug-resistant phenotypes, resulting in a poor prognosis for these liver cancers[8,17,18].

In this review, we highlight the recent developments in AS events. We will also describe the regulation of AS in primary and metastatic liver cancers. In addition, this review integrates the biological functions of AS and splicing products as well as current efforts to develop their potential for clinical application in the diagnosis or treatment of cancer.

ALTERNATE SPLICING

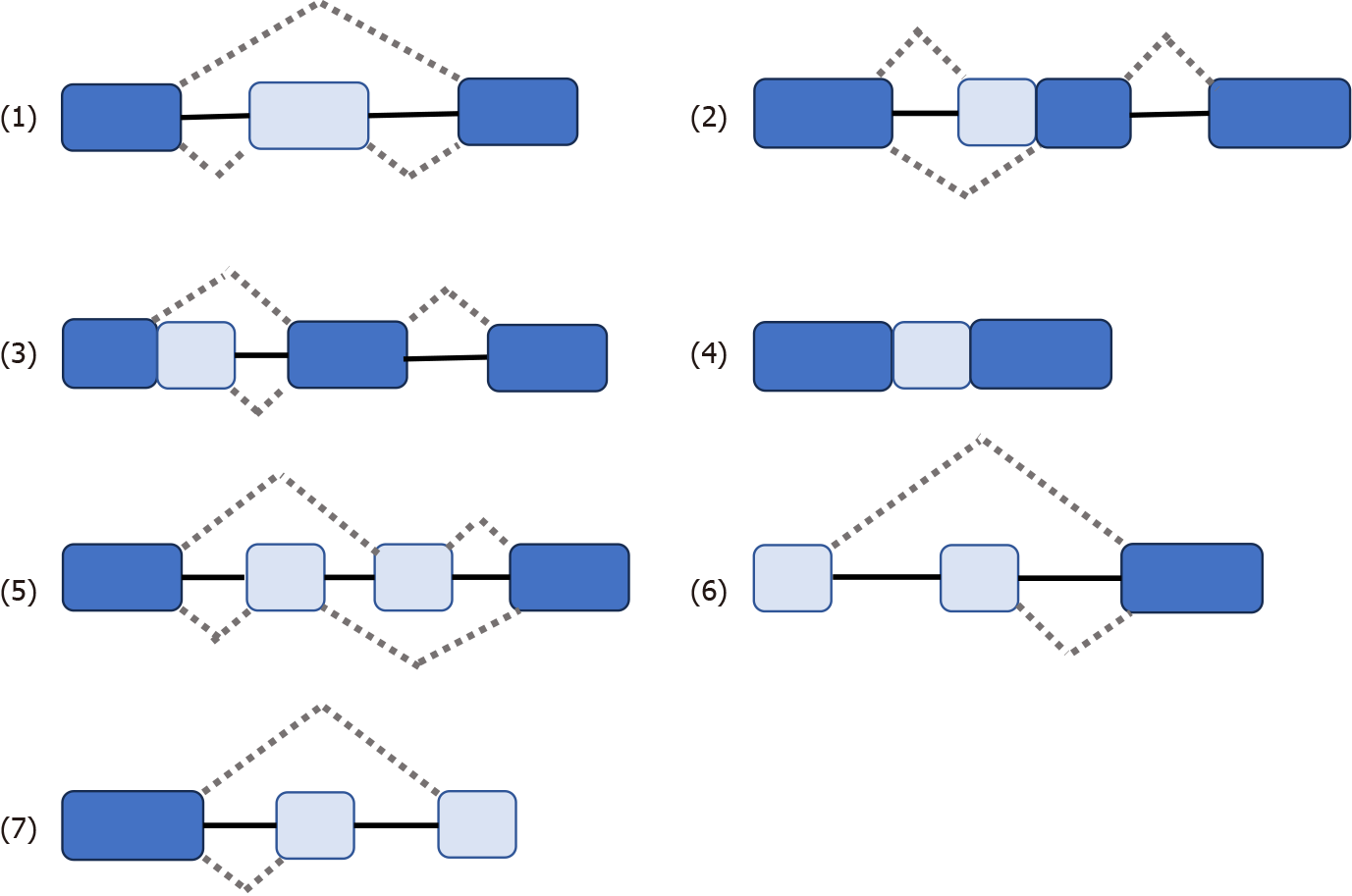

Some genes have one mRNA precursor that produces different mRNA splicing isomers using different splicing methods (choosing different splicing sites) in a process known as variable splicing (or AS)[14,15,18-20]. Variable splicing is the most common and widespread type of splicing[14]. Variable splicing is an important mechanism for regulating gene expression and generating proteomic diversity and is an important reason for the large differences in the number of genes and proteins in eukaryotes[21]. In vivo, there are seven types of variable splicing: (1) Exon skip; (2) Retained intron; (3) Alternate Donor site; (4) Alternate acceptor site; (5) Alternate promoter; (6) Alternate terminator; and (7) Mutually exclusive exons[14,15,17] (Figure 1). During variable splicing, the different exons of a gene sequence are selectively linked to form multiple transcripts. Consequently, the same gene can encode many different proteins, thereby increasing the functional diversity of the gene. This type of splicing is very common in mammals and is found in more than 90% of genes[22]. The development of metastatic cancer is influenced by multifactorial conditions, possibly due to: (1) Altered expression of the spliceosome; (2) mutations affecting genes encoding spliceosome components and related regulatory proteins; (3) disruption of splice site or splicing regulatory sites (enhancers or silencers); and (4) impaired signaling pathways involved in the regulation of splicing mechanisms[17,23,24].

Figure 1 Seven types of variable splicing in vivo.

(1) ES: Exon skip; (2) RI: Retained intron; (3) AD: Alternate Donor site; (4) AA: Alternate acceptor site; (5) AP: Alternate promoter; (6) AT: Alternate terminator; (7) ME: Mutually exclusive exons.

ALTERNATE SPLICING IN PRIMARY LIVER CANCER

Primary HCC tumor tissue exhibits a high degree of differential splicing compared to normal liver tissue. A growing body of research has shown that alterations in the splicing program in HCC tumor cells generate novel protein subtypes that often have different and sometimes opposite functions to their classical counterparts[25]. These changes were significantly associated with patient survival[12]. These findings suggest that AS plays a crucial role in HCC progression and prognosis. Primary liver cancer includes various tumors such as HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (iCCA)[26]. One study showed that differences between HCC and iCCA AS affected hundreds of genes[19]. Thus, alternative and tumor-specific subtypes caused by abnormal splicing are common during liver tumorigenesis[21,27].

AS disorder is also associated with the pathogenesis of liver cancer. For example: Loss of SRSF3 induces IGF2 expression and altering INSR splicing to allow insulin-like growth factor II (IGF2) signaling to be conducted through insulin receptor (IR)-A in hepatocytes[28]. Hepatic IGF2 expression is a carcinogenic driver in aging-related HCC mouse models, causing DNA damage and supporting hepatocyte proliferation. This allowed for the accumulation of somatic mutations. EGFR regulates the selective splicing of IR pre-mRNA in HCC cells. After ligand binding, EGFR activation triggers an intracellular signaling cascade, which implies MEK activation. This stimulates the transcription of genes encoding different splicing factors, namely CUGBP1, hnRNPH, hnRNPA1, hnRNPA2B1, and SF2/ASF. hnRNPF expression is not regulated by the EGFR-dependent pathway. Interaction between splicing factors and IR pre-mRNA promotes the selective splicing of IR exon 11. Consequently, the expression of the IR-A subtype increases to the detriment of IR-B, which allows for the transmission of proliferative signals in response to insulin and IGF2, leading to HCC development[29].

In summary, the dysregulation of AS in liver cancer has been shown to affect various molecular pathways, underscoring the influence of AS dysregulation on the molecular mechanisms of liver cancer development and its extensive involvement in the pathogenesis, progression, and prognosis of HCC. The replacement of gene products produced by abnormal splicing has been linked to positive effects in cancer, making AS a potential target for gene therapy[30]. These findings suggest that understanding AS in liver cancer may lead to the development of novel therapeutic interventions.

METASTASIS MECHANISMS IN METASTATIC LIVER CANCER

Pathogenesis of metastatic liver cancer involves a complex interplay of molecular mechanisms, including the role of splicing factors in cancer progression, AS, and hypoxia-induced splicing changes[31].

Splicing factor changes in metastasis liver cancer

The role of splicing factors in metastatic liver cancer has attracted increasing interest in cancer research. Splicing factors, including those in metastatic liver cancer, play a direct role in cancer development[32]. Abnormal RNA splicing has been recognized as a driver of cancer development and changes in AS of RNA have been associated with liver cancer progression[26]. In addition, alterations in splicing are associated with liver cancer markers, including de-differentiation and genomic instability, which are the core processes of tumor transformation[16].

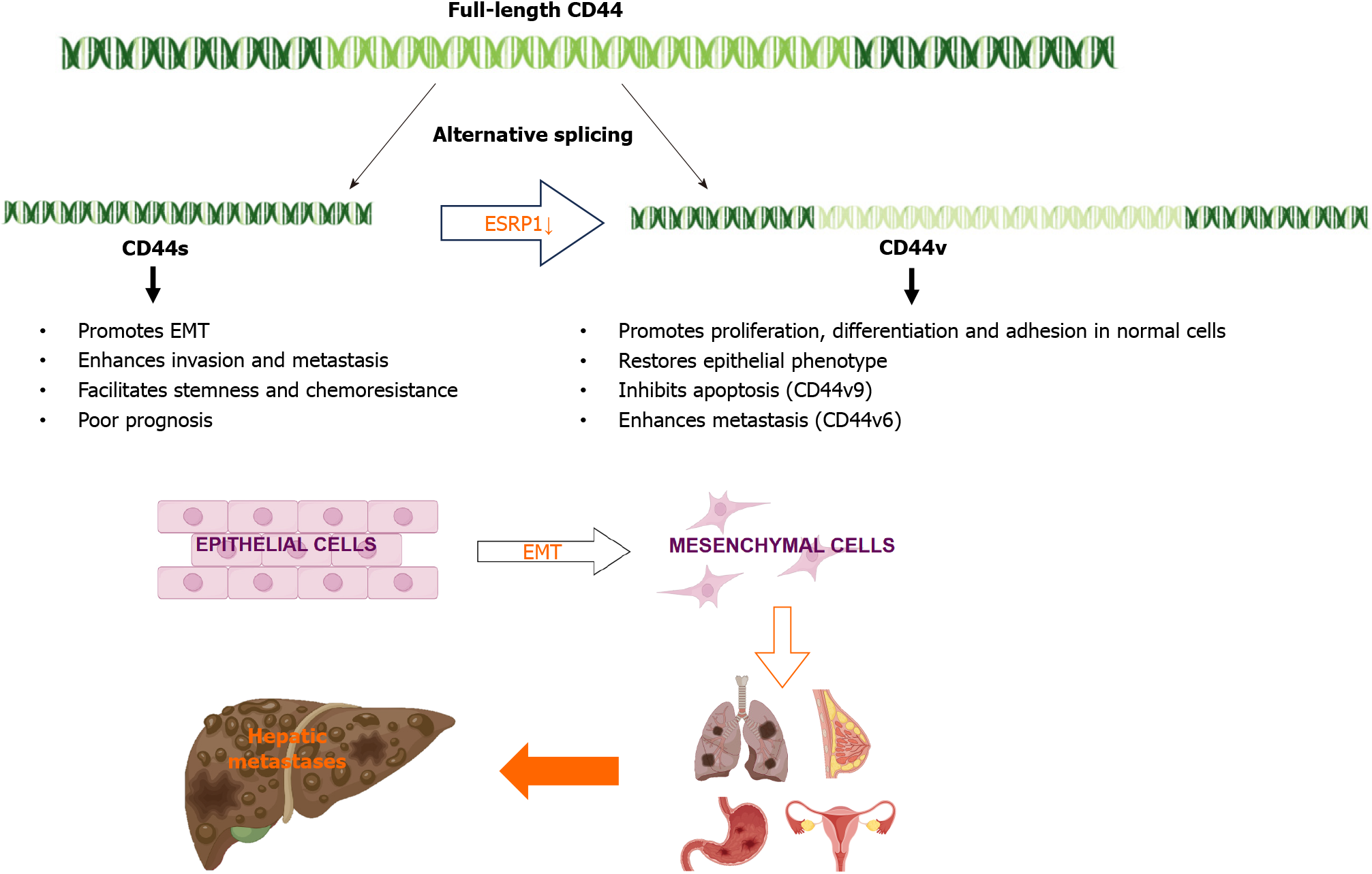

In liver cancer, the AS of specific genes has been shown to contribute to cancer progression and metastasis. For example, epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 (ESRP1) plays a key role in the regulation of CD44 AS[33]. ESRP1 is an epithelium-specific splicing factor that regulates the AS of several genes, including fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 and CD44[34]. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a specific biological process in which epithelial cells are transformed into stromal cells. It is important for epithelial cell-derived malignant tumor cells to acquire migration and invasion abilities. EMT plays a crucial part in embryonic development, chronic inflammation, tissue reconstruction, cancer metastasis, and various fibrotic diseases[35]. The main characteristics of EMT include reduced expression of cell adhesion molecules (such as E-cadherin), transformation of the cytoskeleton from keratin to vimentin, and altered morphological characteristics of mesenchymal cells. Through EMT, epithelial cells lose cell polarity, their connection to the basement membrane, and other epithelial phenotypes, while gaining higher interstitial phenotypes, such as migration and invasion, apoptosis inhibition, and degradation of the extracellular matrix[36]. During EMT, ESRP1 expression is sharply reduced, facilitating the transition from variant CD44 (CD44v) to standard CD44 (CD44s), mediating the expression of isoforms required for EMT. ESRP1 promotes liver metastasis in breast cancer cells by enhancing EMT[34]. ESRP1 regulates subtype conversion and determines gastric cancer metastasis[37]. ESRP1 drives AS of CD44, thereby enhancing invasion and migration of epithelial ovarian cancer cells[38]. ESRP1 has been identified as a favorable prognostic factor for pancreatic cancer[39], alleviating pancreatic metastasis. In contrast, the silencing of ESRP1 has been shown to drive the malignant transformation of human lung epithelial cells[40], suggesting that cancer progression is strongly influenced by splicing factors (Figure 2).

Figure 2 During Epithelial-mesenchymal transition, epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1 expression is reduced, promoting the transition from variant CD44 to standard CD44, and can promote liver metastasis of lung, breast, stomach, and ovarian cancers.

CD44s: Standard CD44; CD44v: Variant CD44; ESRP1: Epithelial splicing regulatory protein 1; EMT: Epithelial-mesenchymal transition.

Abnormal splicing in metastatic liver cancer

AS events have been identified as prognostic factors for HCC, highlighting their potential impact on the development and prognosis of liver cancer[41]. Various AS events may also influence the development of metastatic liver cancer. Studies have shown that abnormal AS events promote malignant cancer progression[42].

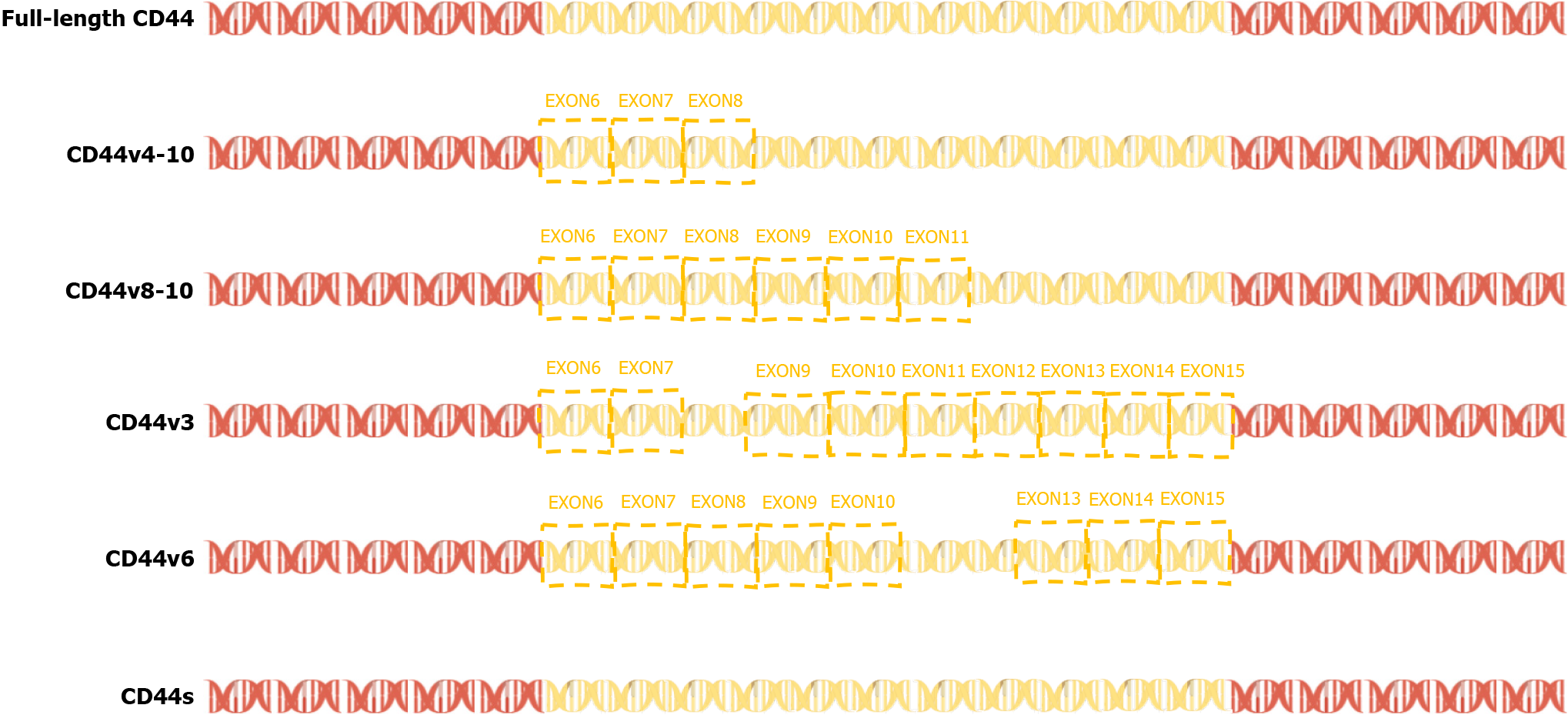

In 2015, a team found that PC-3 and its derived cell lines crossed the transfer barrier in vitro and in vivo, providing an excellent, unbiased system for comprehensively characterizing AS events and identifying the key splicing factors that influence the splicing regulation of transfer. This suggests that partially selective splicing events are associated with metastatic colonization of cancer cells, suggesting a potential role in promoting metastasis[43]. Liver metastasis may occur in different tumors, and different splicing events may promote liver metastasis. For example, the splicing mediated by RBFOX2 shifts from an epithelial-specific event to a mesenchymal-specific event, leading to a higher degree of tissue invasion, which in turn leads to liver metastasis[44]. Different splicing subtypes of the same spliceosome, such as CD44, promote liver metastasis. CD44 is a cell surface glycoprotein involved in cancer progression and metastasis. AS of CD44 mRNA produces various subtypes, including CD44s and CD44v (Figure 3), which are associated with cancer metastasis. The CD44-ZEB1-ESRP1 feedback loop can control the cell phenotype and prognosis of patients with cancer by determining the CD44 subtype expression[45]. Some splicing events that lead to liver cancer metastasis, such as the overexpression of IGF2 and decreased splicing activity of SRSF3, are considered major causes of DNA damage and drivers of liver cancer, indicating the importance of specific splicing factors in liver cancer development. While affecting the process of liver metastasis, it also affects changes in tumor drug resistance. The FUS/circEZH2/KLF5 feedback loop promotes liver metastasis of breast cancer by FUS promoting the reverse splicing process of circEZH2 by binding to the 3’-lateral intron portion of pre-EZH2 to enhance the EMT, and may also influence drug resistance of liver metastases through this mechanism[46]. In summary, AS events are involved in the occurrence and development of metastatic liver cancer, highlighting the importance of splicing regulation in cancer progression and metastasis.

Figure 3 Exons 6-14 of CD44 gene undergo alternative splicing in the membrane-proximal stem region, resulting in a variety of variable splicing variants (CD44 variant isoform, variant CD44; Including CD44v2-v10).

CD44s: Standard CD44; CD44v: Variant CD44.

Hypoxia-induced splicing changes in metastasis liver cancer

Hypoxia is associated with changes in EMT, angiogenesis, local tissue invasion, endothelium, exocytosis, and pre-metastatic niche formation[47]. Hypoxia, a hallmark of the tumor microenvironment, induces AS, thereby promoting the invasive behavior of cancer cells[31]. Hypoxia inhibits cancer cell differentiation and promotes cancer cell invasion and metastasis, emphasizing its role in promoting cancer cell metastasis[48]. Hypoxia-induced splicing changes play a crucial role in the occurrence and progression of cancer metastasis. Hypoxia-induced selective splicing is cell type-specific and has highly conserved universal target genes, indicating that hypoxia has a broad impact on splicing[49]. In the DNA damage response, hypoxia drives the selective splicing of genes towards non-coding subtypes by increasing intron retention[50]. Similarly, hypoxia promotes the expression of splicing subtypes of Myc-related factor X in endothelial cells, mediated by nonsense decay degradation, and another splicing subtype that encodes unstable proteins[51].

Hypoxia leads to significant changes in the selective splicing of prostate cancer cells and increased expression of CLK splicing factor kinase, leading to liver metastasis[52]. In addition, hypoxia regulates CD44 and its variant subtypes through HIF-1α in triple-negative breast cancer, highlighting the role of hypoxia in regulating various splicing events associated with cancer progression[48].

The effect of hypoxia on AS has been recognized as a powerful driving force for tumor pathogenesis and progression, and various studies have emphasized the important influence of hypoxia-induced splicing changes on the pathogenesis of metastatic liver cancer. Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying hypoxia-induced splicing changes is essential for developing targeted therapeutic strategies to mitigate the invasive behavior of metastatic liver cancer cells and improve patient outcomes.

DISCUSSION

The liver has a rich blood supply, so it provides fertile “soil” for metastasis to spread[53]. The liver is one of the largest blood vessel networks in the body. It receives blood from the gut, which contains a lot of nutrients. The blood vessels at the end of the liver also have high pressure, so it is easier to accommodate and colonize metastasized cancer cells[54]. The most common source of metastatic liver cancer is colorectal cancer, followed by pancreatic, breast, melanoma and lung cancer. The common ways of metastasis include direct invasion, lymphatic metastasis and blood-derived metastasis. Malignant tumors that directly invade the organs and tissues around the liver, such as gastric cancer, gallbladder cancer, pancreatic cancer, colon cancer and duodenal cancer. Lymphatic metastasis is more common in digestive system malignancies, pelvic or retroperitoneal malignancies, breast cancer, lung cancer and gallbladder cancer. Hematogenous metastasis can also be further subdivided into hepatic artery and portal vein metastasis. Any tumor cells entering the liver through these vessels can cause liver metastasis, such as esophageal and gastrointestinal tumors and some sarcomatoid tumors with higher malignant degree.

Metastatic liver cancer presents significant clinical challenges owing to its aggressiveness, poor prognosis, and limited treatment options. Studies based on the SEER database emphasize that patients with primary extrahepatic metastases have poor prognosis[55]. In 2020, a practical study of high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation in 250 patients, including a primary liver cancer cohort (n = 80) and metastatic liver cancer cohort (n = 195), yielded 1-year survival rates of 70.69% and 48.00%, respectively[56]. These findings highlight the need for innovative therapeutic modalities to address the adverse effects of metastatic liver cancer. Metastatic liver cancer is a serious detrimental condition. Addressing the challenges associated with metastatic liver cancer requires a comprehensive understanding of its harmful nature and development of targeted treatment strategies.

Mechanisms underlying liver cancer metastasis are complex. In 2012, Biamonti et al[57] explored the role of AS in EMT, elucidating the link between AS and the invasive abilities of cancer cells. Understanding the effects of AS on EMT is critical for elucidating the underlying mechanisms of cancer metastasis and drug resistance. Next, a systematic review of liver transplantation in patients with liver metastases from neuroendocrine tumors highlighted the challenges posed by high recurrence rates, underscoring the need for precise patient selection and new treatment strategies[58]. Breakthroughs in the understanding of variable splicing in metastatic liver cancer have the potential to revolutionize cancer treatment. A comprehensive analysis of tumor AS in 8705 patients showed that tumors had 30% more AS events than normal samples[59]. This highlights the importance of AS in cancer, including metastatic cancer, and illustrates the potential of targeting splicing events for therapeutic interventions. In addition, the 2021 study by Fish et al[60] identified a previously unknown structural splicing enhancer rich in near-box exons with increased inclusions in highly metastatic cells. These findings provide valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of metastasis and offer potential targets for the suppression of cancer metastasis. Subsequently, 2022 revealed an FUS/circEZH2/KLF5 feedback loop that promoted liver metastasis of cancer by enhancing EMT[46]. These findings provide insights into the molecular pathways of liver metastasis and a potential target for therapeutic intervention.

Metastatic liver cancer is a complex and multifaceted disease, and AS has been identified as a key factor in its progression. Several themes regarding the role of AS in metastatic liver cancer have emerged in the literature. AS is associated with EMT, a key process in cancer metastasis[57]. In addition, the splicing of specific genes such as CD44 has been shown to enhance the metastatic potential of cancer cells[61-63]. In addition, regulatory strategies to control AS in cancers, including metastatic liver cancer, remain largely unknown, suggesting gaps in our understanding of the underlying mechanisms[37,60]. In addition, associations between AS and metastatic phenotypes have been studied in various types of cancers, including colorectal and prostate cancers, suggesting that AS has a broader relevance in cancer metastasis[64,65]. Despite these insights, the existing studies of AS for metastatic liver cancer have some shortcomings. The functional mechanisms of AS in cancer, particularly liver metastasis, remain unclear[46,66]. Although a link between AS and cancer metastasis has been established, the specific regulatory procedures governing this process remain unclear[60]. In addition, the literature highlights the disappointing outcomes of liver transplantation for both primary and metastatic liver cancers, suggesting a lack of effective treatment strategies for metastatic liver disease[67]. This finding suggests that further research is needed to develop new treatment options for metastatic liver cancer. However, significant gaps exist in our understanding of the functional mechanisms and regulatory processes involved in AS in metastatic liver cancer. Addressing these gaps is critical for developing effective interventions for this challenging disease. This article is the first review of variable splicing in metastatic liver cancer, with the hope of providing new directions for future research.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, the importance of variable splicing in the development of liver metastases has been increasingly recognized. These breakthroughs underscore the potential of targeting AS events and related molecular pathways to inhibit the development and progression of metastatic cancers. Further research and clinical studies are essential to translate these findings into effective treatments for patients with metastatic liver cancer.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yoshinaga K, Japan S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yuan YY