Published online Feb 24, 2024. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v15.i2.329

Peer-review started: October 1, 2023

First decision: November 29, 2023

Revised: December 24, 2023

Accepted: January 15, 2024

Article in press: January 15, 2024

Published online: February 24, 2024

Processing time: 141 Days and 20.9 Hours

Pyroptosis impacts the development of malignant tumors, yet its role in colorectal cancer (CRC) prognosis remains uncertain.

To assess the prognostic significance of pyroptosis-related genes and their association with CRC immune infiltration.

Gene expression data were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and single-cell RNA sequencing dataset GSE178341 from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Pyroptosis-related gene expression in cell clusters was analyzed, and enrichment analysis was conducted. A pyroptosis-related risk model was developed using the LASSO regression algorithm, with prediction accuracy assessed through K-M and receiver operating characteristic analyses. A nomo

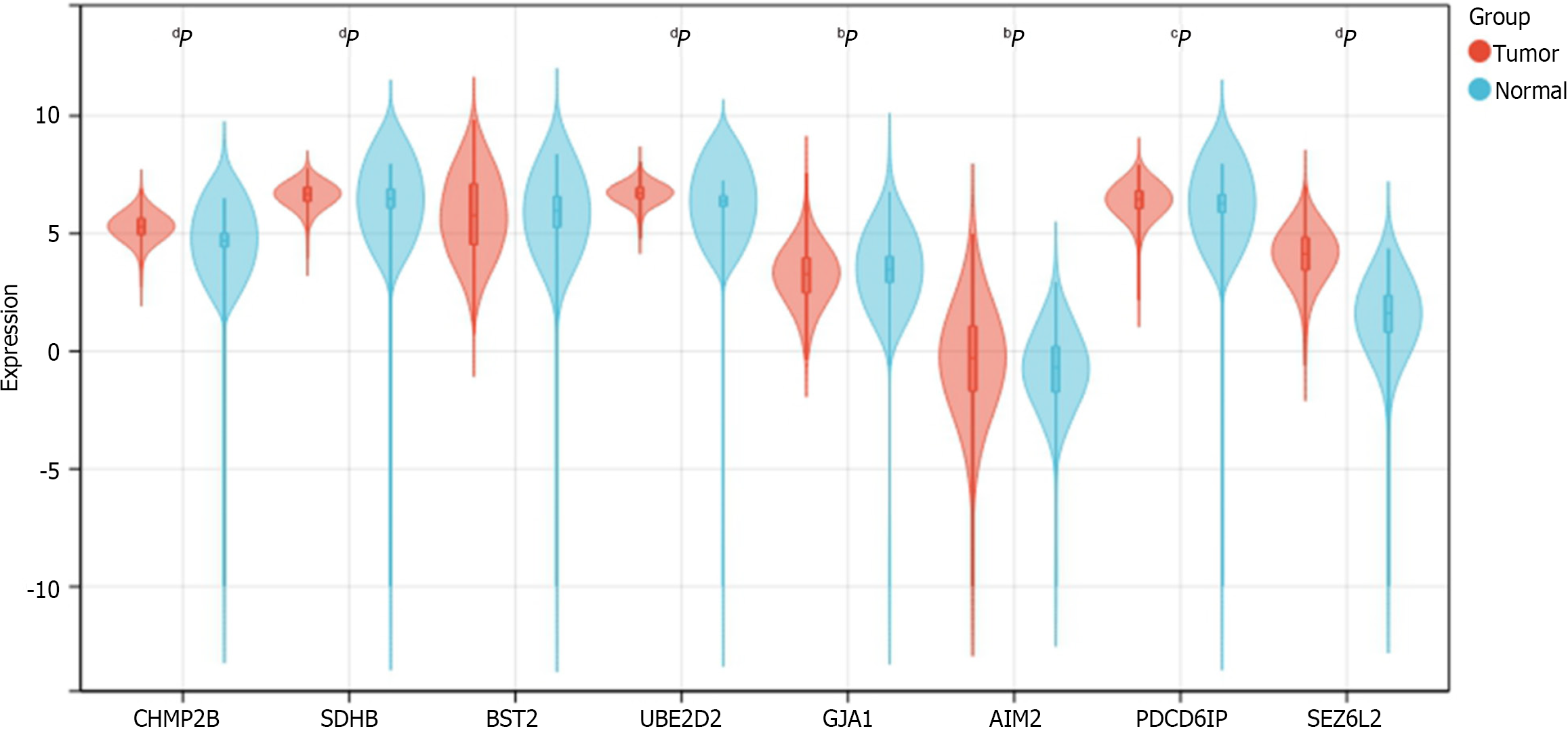

An effective pyroptosis-related risk model was constructed using 8 genes-CHMP2B, SDHB, BST2, UBE2D2, GJA1, AIM2, PDCD6IP, and SEZ6L2 (P < 0.05). Seven of these genes exhibited differential expression between CRC and normal samples based on TCGA database analysis (P < 0.05). Patients with higher risk scores demonstrated increased death risk and reduced overall survival (P < 0.05). Significant differences in immune infiltration were observed between low- and high-risk groups, correlating with pyroptosis-related gene expression.

We developed a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for CRC, affirming its correlation with immune infiltration. This model may prove useful for CRC prognostic evaluation.

Core Tip: We constructed a prognostic model related to pyroptosis in colorectal cancer (CRC) and confirmed the correlation with immune infiltration. This model may be useful for prognostic assessment of CRC.

- Citation: Zhu LH, Yang J, Zhang YF, Yan L, Lin WR, Liu WQ. Identification and validation of a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for colorectal cancer based on bulk and single-cell RNA sequencing data. World J Clin Oncol 2024; 15(2): 329-355

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v15/i2/329.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v15.i2.329

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the prevalent malignancy and consider the second most common cause of cancer deaths globally[1,2]. Genetic, lifestyle, obesity and environmental factors are considered as main causative agents of CRC[3]. Besides, changes in the microenvironment of cells also proved to affect the growth development of this disease[4-8]. The prognosis for CRC is grim, with nearly 20% of patients progressing to stage 4 and an additional 20%-50% of early-stage patients developing metastatic disease[9]. While immunotherapy introduces a promising avenue for CRC treatment, its effectiveness hinges on the intricacies of the immune microenvironment[10-12]. Although numerous biomarkers identified through traditional methods based on bulk RNA sequencing, such as methylation[13], lncRNA[14], and IGFBP-2[15], their accuracy in predicting CRC prognosis and the association with the tumor microenvironment (TME) is insufficient. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop a novel prognostic model with advanced technology for effective risk stratification and prediction of immunotherapy outcomes in CRC.

Pyroptosis, defined as gasdermin-mediated programmed cell death, has been established to influence tumor development[16-19]. By modulating the immune microenvironment, pyroptosis plays a crucial role in the prognosis of various cancers, including CRC. Notably, pyroptosis-related genes like IL-18, CASP1, GSDMB, and GASP5 have been utilized to construct prognostic models for bladder, ovarian, and gastric cancers[20-22]. However, many of these models relied on bulk RNA sequencing levels, and adequate pyroptosis-related prognostic models specifically tailored for CRC are lacking.

To date, single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as the optimal method for discovering, identifying, and validating new biomarkers, particularly in TME research[23]. This technique offers genomic and transcriptomic insights into cancers at the single-cell RNA level, surpassing the limitations of bulk RNA sequencing[24-27]. Leveraging scRNA-seq, we developed a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for CRC and explored potential correlations between pyroptosis and immune infiltration. This study contributes valuable insights for clinical management and immunization research in CRC.

The scRNA-seq dataset GSE178341, obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database[28], encompasses 61 CRC and 27 non-malignant colorectal tissues. This dataset, encompassing diverse clinical conditions, facilitates comprehensive analyses, offering profound insights into the involvement of pyroptosis-related genes in CRC. Additionally, its widespread use allows for robust comparisons and validation with other studies, augmenting the reliability of our research outcomes. The “The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) biolinks” package of R software (version 2.22.4)[19] was employed to retrieve TCGA-colon adenocarcinoma (TCGA-COAD) and TCGA-rectum adenocarcinoma (TCGA-READ) raw counts expression data and clinical data, comprising 578 CRC tumor samples and 106 paracancer samples. Merging these two expression matrices resulted in a baseline fact sheet with 619 cases containing clinical information (Table 1). Prognostic analyses were conducted on the samples that contained COAD and READ data.

| Characteristic | Levels | Overall, n = 619 |

| Pathologic stage | Stage I | 105 (17.5) |

| Stage II | 227 (37.9) | |

| Stage III | 179 (29.9) | |

| Stage IV | 88 (14.7) | |

| Gender | Female | 289 (46.7) |

| Male | 330 (53.3) | |

| Age | ≤ 65 | 269 (43.5) |

| > 65 | 350 (56.5) | |

| BMI | < 25 | 98 (32.2) |

| ≥ 25 | 206 (67.8) |

The R software (https://www.r-project.org/, version 4.1) and the R package Seurat (version 4.0.5)[29] were installed, and the expression matrix of the GSE178341 dataset was created as a Seurat object. Cells with > 20% mitochondrial genes, potentially indicating a stressful state, were excluded. Cells with FEATURE < 200 or > 3000 were also filtered, resulting in 115489 cells.

Subsequently, the sequencing depth of the dataset was normalized using the “NormalizeData” function with the default “LogNormalize” standardization method. The “FindVariableFeatures” function, employing the “vst” method, identified 2000 variable features of the dataset. Data scaling, utilizing the “ScaleData” function, mitigated the impact of sequencing depth. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) identified significant PCs[30], and the Elbowplot function visualized the P value distribution. For the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) analysis, 30 PCs were selected. The Louvain algorithm, through the “FindClusters” function, optimized class groups, resulting in 38 different clusters with a resolution of 0.8. Finally, the “RunUMAP” function enabled dimensionality reduction for dataset visualization and exploration. The “FindAllMarkers” function compared gene expression of cell clusters with the gene expression of all other cell clusters.

The Blueprint Encode in SingleR (version 1.8.1)[31] was employed to annotate cell types in the single-cell data. Identified cell types included T cells, NK cells, B cells, plasma cells, epithelial cells, myeloid cells (DC, Macrophage, Monocyte), stromal cells, mast cells, and endothelial cells. Differential genes between cell types were identified using the “FindAllMarkers” function.

A total of 427 pyroptosis-related genes were obtained from the Gene Cards database (https://www.genecards.org/)[32] (Supplementary Table 1). The genes were intersected with marker genes of cell clusters for obtaining the pyroptosis-related differently expressed genes (DEGs) among cell clusters, A heat map illustrating the expression of DEGs in cell clusters was generated using the “DoHeatmap” function.

Pyroptosis-related DEGs expressing in specific cell types were visualized using the “FeaturePlot” from Seurat. The Pearson correlation coefficient of pyroptosis-related DEGs between cells was calculated using the corr R package. The correlation network was plotted using the “network_plot” function.

The CellChat R package (version 1.1.3)[33] was used to quantitatively infer and analyze the communication network between the identified 11 cell clusters. A circle diagram depicted the interaction between cell groups, while a bubble diagram counted all important ligand pairs during intercellular signaling.

The “c2.cp.kegg.v7.5.1.symbols.gmt” geneset was downloaded from the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/)[34]. The “gsva” method of the R package GSVA (version 1.42.0) was employed for analyzing CRC single-cell data. Gene expression data from an expression matrix with individual genes as features were transformed into an expression matrix with specific genesets as features. The expression matrix was transformed into an enrichment score (ES) matrix for the pathway, obtaining a GSVA ES for each cell corresponding to each pathway. Using the limma R package (version 3.50.0)[35], pathways with significant differences (P < 0.05) were analyzed, and pathway activity scores for each cell group were compared with all other cell groups. The top 3 pathways in each group, ranked from the largest to the smallest t-value, were selected for plotting the heat map.

The TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ transcriptome data underwent quantitative conversion into absolute abundance of immune and stromal cells using the “CIBERSORTx” method[36,37]. This method assessed changes in the proportion of immune cell subsets, including memory B cells, naive B cells, activated dendritic cells, resting dendritic cells, eosinophils, M0 macrophages, M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages, activated mast cells, resting mast cells, monocytes, neutrophils, activated NK cells, resting NK cells, plasma cells, activated memory CD4+ T cells, resting memory CD4+ T cells, naive CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, T follicular helper cells, gamma delta T cells, and regulatory T cells (Tregs). Significant differences between groups with high and low risk were assessed using the t-test method, considering P values < 0.05 as significant.

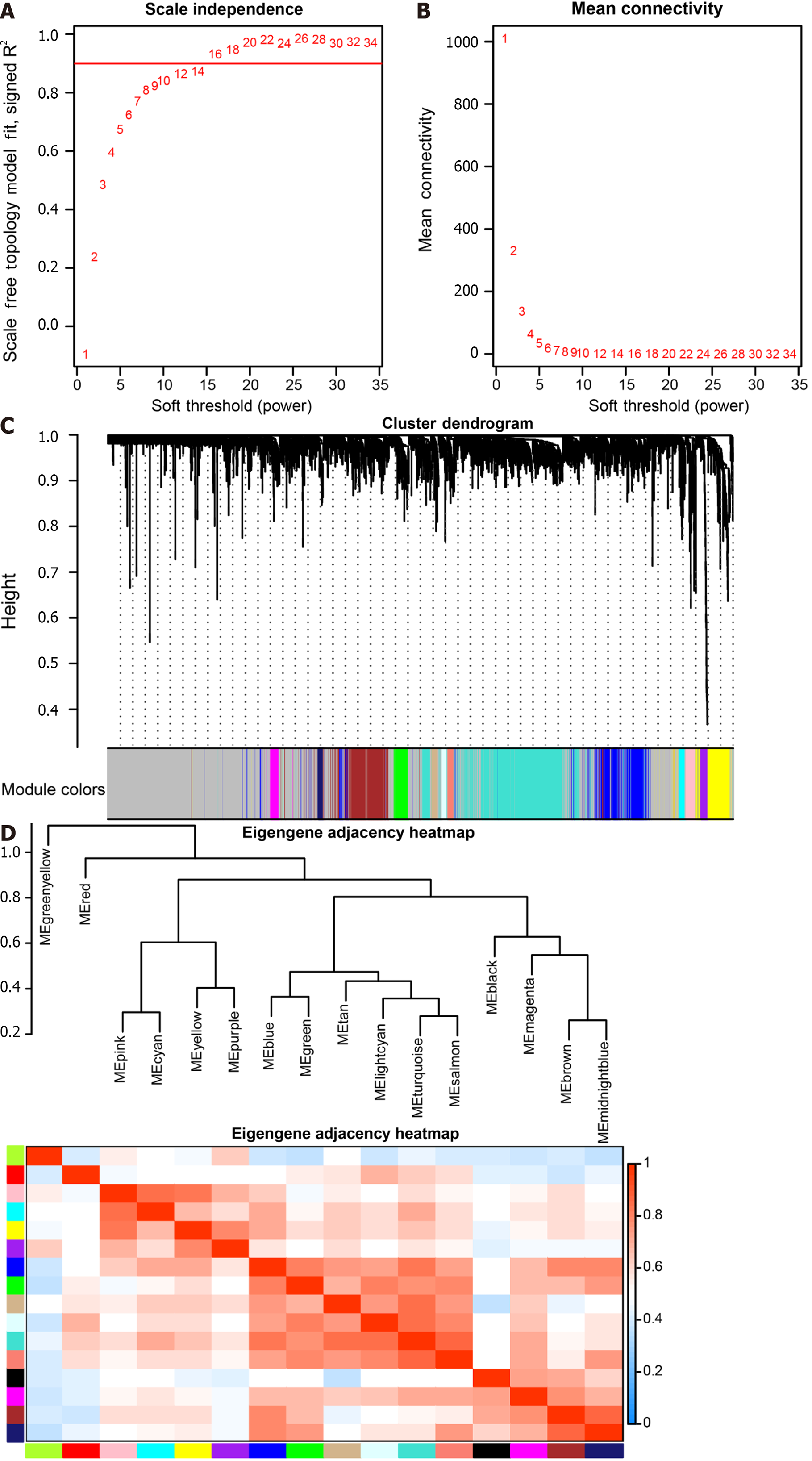

Weighted co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) was employed to construct co-expression networks and identify modules of highly correlated genes[38,39]. The COAD and READ datasets from TCGA were selected as the trait data for WGCNA.

DESeq2 (version 1.34.0)[40] from the R software package was used for analyzing the differential expression of pyroptosis-related genes in TCGA-CRC data. Pyroptosis-related DEGs were identified with a screening threshold of P value < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.5. Clustered heat maps, volcano maps, and Gene Ontology (GO) functional enrichment maps for the relevant genes were generated.

In GO enrichment analyses, each term in biological process (BP), molecular function (MF), and cellular component was analyzed for enrichment significance[41]. This method was applied to characterize the features of pyroptosis-related genes.

Consensus Clustering, a tool for cancer subtype classification, was used for analysis on the 178 key genes derived from scRNA-seq and TCGA datasets using the ConsensusClusterPlus (Version 1.58.0) package of R software[42]. The distance calculation method was Spearman, and the clustering algorithm was PAM (Partitioning Around Medoids). Consistent cumulative distribution function maps, Delta Area Plots, and consistency matrix heat maps were utilized for clustering analysis.

Initially, the pyroptosis-related DEGs underwent univariate Cox analysis to identify genes with significant prognostic value. Subsequently, CRC samples were randomly divided into two parts, with a ratio of 7:3 for training and validation of the prognostic model. The LASSO-COX regression algorithm was applied to establish the prognostic model, and the risk score calculation formula was defined as: RiskScore =∑iCoefficient (genei) × expression (genei).

Where “coef (k)” represents the multivariate Cox regression coefficient; “x (k)” represents the expression value of each single gene, and “n” represents the number of genes.

Initially, the 606 CRC samples were divided into two groups based on high and low risk scores using the median risk score. Subsequently, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were conducted to assess the prognostic accuracy for OS. The risk scores were compared under different clinical feature groups, including age, gender, and TNM stage.

To illustrate the predictive ability of risk scores combined with clinicopathologic characteristics for patient prognosis, both were incorporated into the model. A clinical predictive nomogram was constructed to predict risk, and its predictive ability was evaluated using calibration curves by comparing predicted values with actual survival rates. OS of the predicted scores was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier, and the prognostic accuracy of the model was tested using time ROC analysis.

Tumor mutational burden (TMB), reflecting the quantity of cancer mutations[43], was calculated using the “Maftools” package of R software (version 2.10.0). The somatic mutation levels in TCGA CRC samples were assessed, and the top 10 high-frequency mutated genes were counted to generate a waterfall plot. Subsequently, the impact on survival was explored by grouping according to high or low TMB levels, and comparisons were made between TMB differences in the two groups.

To validate the expression of the 8 prognostic genes between CRC and normal samples, we obtained the uniformly normalized pan-cancer dataset of TCGA TARGET GTEx (PANCAN, n = 19131, G = 60499) from the UCSC (https://xenabrowser.net/) database. Expression data for ENSG00000083937 (CHMP2B), ENSG00000117118 (SDHB), ENSG00000130303 (BST2), ENSG00000131508 (UBE2D2), ENSG00000152661 (GJA1), ENSG00000163568 (AIM2), ENSG00000170248 (PDCD6IP), and ENSG00000174938 (SEZ6L2) in samples from solid tissue normal, primary solid tumor, primary tumor, normal tissue, primary blood derived cancer-bone marrow, and primary blood derived cancer-peripheral blood were downloaded. A log2 (x + 0.001) transformation was applied to each expression value, and the analysis was restricted to CRC. Expression differences between normal and tumor samples were calculated for each tumor using R software. The significance of differences was assessed using unpaired Wilcoxon Rank Sum and Signed Rank Tests. The expression data of the 8 genes in CRC were provided in Supplementary Table 2.

All calculations and analyses were performed using the R programming language. The risk model was constructed using LASSO and COX regression analyses.

The scRNA-seq data from 88 CRC samples underwent analysis, resulting in the identification of 115489 cells after adherence to quality control standards. Standardization and normalization of the data facilitated the extraction of the top 2000 high-variant genes. Subsequently, the selected high-variant genes underwent downscaled by PCA algorithm, followed by clustering analysis using the SNN algorithm. Visualization of the PCA-based downscaling results was achieved through UMAP for single-cell clustering. The successful classification of 115489 cells into 38 independent clusters is depicted in Figure 1A, and differential marker genes for each cluster are outlined in Supplementary Table 3. Using Single R, 11 distinct cell subsets (epithelial cell, myeloid cells, macrophage, monocyte, mast cells, endothelial cells, stromal cell, plasma, B cells, NK cells, and T cells) were identified (Figure 1B). Subsequently, expression patterns of selected datasets corresponding to markers in published articles were visually represented through bubble plots (Figure 1C). Violin plots illustrated differentially marked genes for each cell subset (Figure 1D), and heat maps displayed the top 2 differentially marked genes for each cell type (Figure 1E). The distribution of cells in CRC tissues (T) and non-CRC tissues (N) across each cell type is illustrated in Figure 1F. Notably, T cells are more predominant in CRC tissues, while plasma/B cells are more prevalent in non-CRC tissues. A comparative UMAP plot in tumor and normal samples is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

We intersected the differential genes between cell types and pyroptosis-related genes, resulting in 125 pyroptosis-related DEGs (Supplementary Table 4). Subsequently, we utilized a heat map to depict the expression of these DEGs in each of the 11 cell subsets (Figure 2A). Notably, among the DEGs, GZMA was specifically expressed in the cluster where NK cells and T cells are located (Figure 2B), while IL-1B was found to be specifically expressed in Monocytes (Figure 2C). The correlation among intersecting pyroptosis-related genes was visualized in Figure 2D. Notably, genes such as APOE, VIM, and STAT3 exhibited a high degree of correlation.

We utilized CellChat to construct a graph displaying the total number of interactions among 11 cell subsets and their overall interaction intensity (Figure 3A). The statistical plot depicting cellular interactions identified by CellChat is presented in Supplementary Figure 2. For a clearer examination of interactions among cell subsets, we conducted subset analysis (Figure 3B), resulting in the division of subsets into 27 subclusters (Supplementary Table 5) [B cells: B01, 2138, 1.85%; B02, 1101, 0.95%; B03, 10239, 8.87%; B04, 42, 0.04%. Plasma 1, 8620, Plasma 2, 1491, 1.29%; Plasmablasts, 168, 0.15%. Dendritic cells (DC): DC1, 568, 0.49%; DC2, 891, 0.77%; pDC, 334, 0.29%. Endothelial cells (Endo): Endo, 2636, 2.28%. Epithelial cells: Epithelial Normal (EpiN), 10480, 9.07%. Epithelial tumor (EpiT): 21614, 18.72%. Fibroblasts: FB1, 1329, 1.15%; FB2, 855, 0.74%. Macrophages: M01, 4020, 3.48%; M02, 1593, 1.38%. Mast, 1286, 1.11%; Monocytes, 4804, 4.16%; Mural, 1162, 1.01%; NK, 6448, 5.58%; Schwann, 159, 0.14%; T cells: T01, 12099, 10.48%; T02, 5772, 5.00%; T03, 7925, 6.86%; T04, 6071, 5.26%; T05, 1644, 1.42%]. Based on the 27 cell subclusters, a CellChat heatmap analysis was performed (Figure 3C), identifying 5 key cell subclusters (M01 Macrophage, T05 T cell, FB2 Fibroblast, Plasmablasts, Schwann) for subsequent analysis. The SPP1 signaling pathway influences the effectiveness of immunotherapy in CRC[44]. We individually aligned for CellChat visualization (Figure 3D). It is evident that the M01 subcluster of macrophages was highly active in the SPP1 signaling pathway. Interestingly, the M02 subcluster of macrophages exhibited minimal activity. Additionally, Schwann cells demonstrated significant activity in the SPP1 signaling pathway. Furthermore, γδ T cells (T05) were correlated with the initiation and progression of immune responses. We analyzed the interaction of T05 Ligands and receptors with other cells (Figure 3E and F). Subsequently, CellChat analysis of the 5 key cell clusters mentioned above was performed with tumor cell clusters (Figure 3G). The close interlinking of the key subclusters was observed. We also noted the enrichment of different metabolic pathways among the cell clusters. Gamma-delta T-cells (T05) were enriched in the cell cycle, DNA replication, and base excision repair pathways, aligning with their function in initiating immune responses. Notably, SPP1-macrophage (M01) was enriched in the toll-like receptor signaling pathway and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction, while M02 was enriched in the pathways of retinol metabolism and linoleic acid metabolism (Figure 3H).

We derived the abundance values of immune cells by utilizing the CIBERSORT online tool to analyze TCGA-COAD and TCGA-READ data. The boxplot visually presents the percentage differences in predicted results among various cell subsets (Figure 4A). Notably, immune cells such as M0 Macrophages, M2 Macrophages, and naïve B cells exhibited significant percentage differences. Subsequently, we eliminated immune cells with 0 abundance in more than half of the samples and constructed a Pearson correlation heatmap depicting relationships among 14 immune cell types (Figure 4B). The correlation analysis revealed strong associations between T cell subtypes, monocytes, and macrophage subtypes. For instance, negative correlations were observed between CD8+ T cells and M0 macrophages (R = -0.4), CD8+ T cells and resting memory CD4+ T cells (R = -0.38), Monocytes and M0 macrophages (R = -0.37), as well as resting memory CD4+ T cells and M0 macrophages (R = -0.28). Conversely, positive correlations were identified between CD8+ T cells and M1 macrophages (r = 0.21) and resting memory CD4+ T cells and Monocytes (r = 0.23).

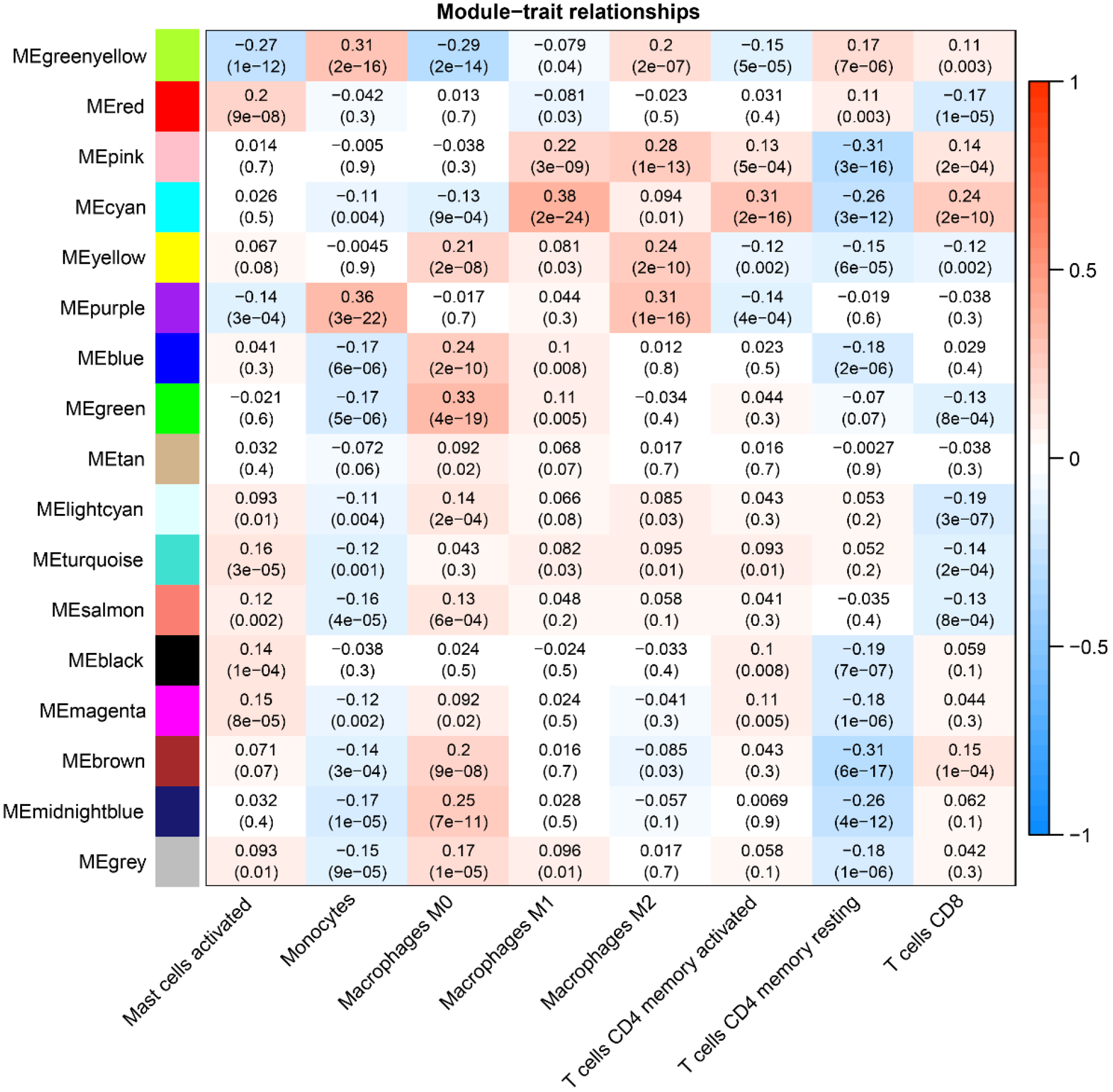

The soft threshold value β was determined to be 16 (Figure 5A and B). Subsequently, we identified 16 modules for further analysis. Hierarchical cluster plots and module correlation heatmaps were generated to visualize the modules (Figure 5C and D). Notably, a significant correlation was observed between the MEcyan module and the M1 Macrophages feature, the MEpurple module and Monocytes and M2 Macrophages features, the MEred module and activated Mast cells, and the Megreen module with M0 Macrophages (Figure 6). From each module, we selected the top 30 genes, resulting in the identification of 120 genes forming the co-expressed gene list (Supplementary Table 6).

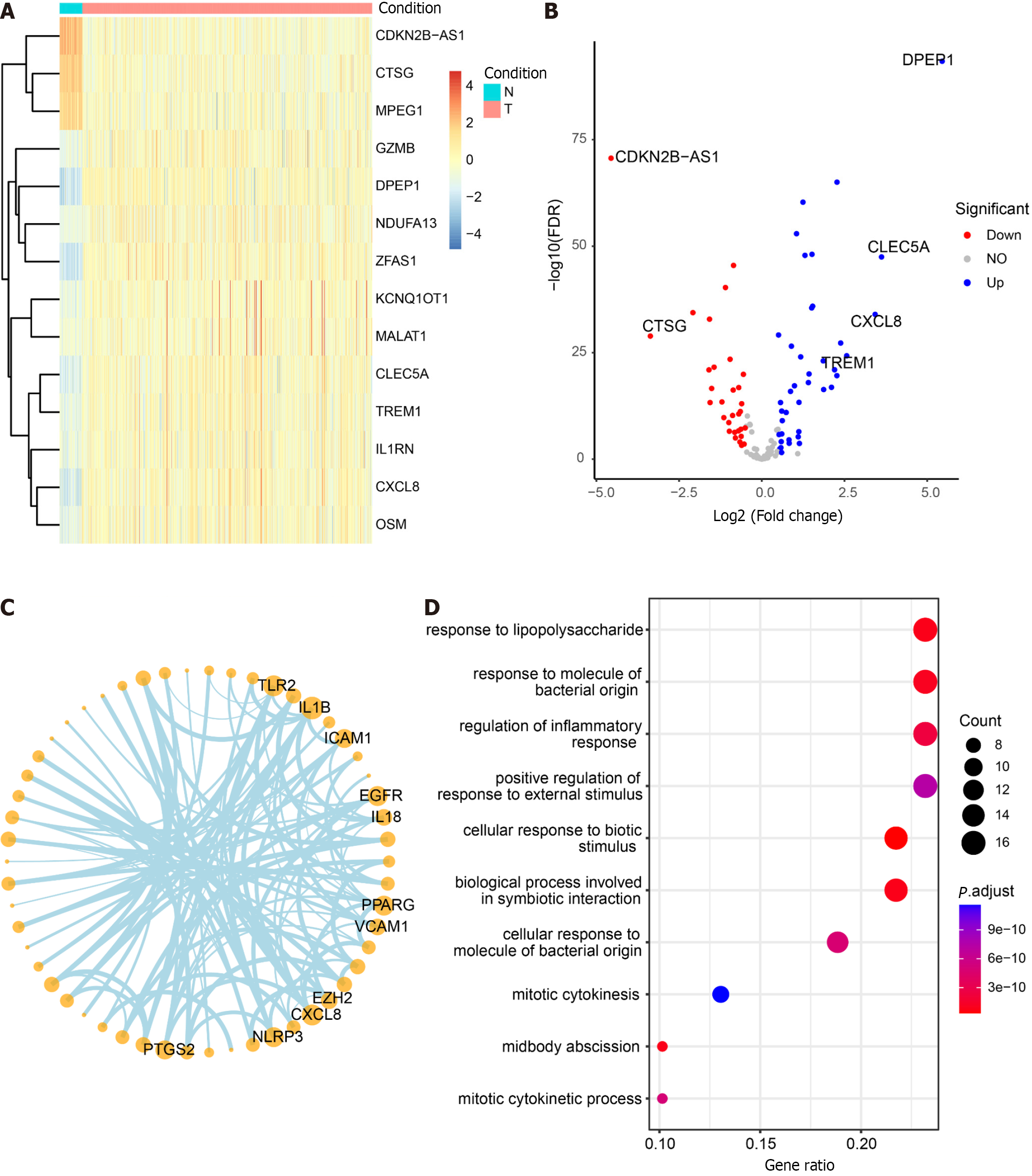

The non-CRC samples from TCGA served as the control group, while the CRC samples were designated as the experimental group for differential analysis (Supplementary Table 7). Among the 125 DEGs, 71 core pyroptosis-related DEGs exhibited significant differential expression in the TCGA dataset (|log2 FC| > 0.5, P < 0.05) (Table 2). The top 14 genes were selected for heatmap display (Figure 7A), and the differential analysis volcano plot provided a visual representation of pyroptosis-related DEGs (Figure 7B), including genes such as CDKN2B-AS1, CTSG, MPEG1, GZMB, and DPEP1, etc., between normal and tumor samples. The Pyroptosis-Related Genes PPI network diagram is presented (Figure 7C, Supplementary Figure 3), with the gene CXCL8 also identified in the differential analysis. Additionally, GO enrichment analysis revealed that the 71 core pyroptosis-related genes were significantly enriched in functions such as the regulation of inflammatory response, mitotic cytokinesis, etc. (Figure 7D, Supplementary Table 8).

| No. | Gene | No. | Gene | No. | Gene |

| 1 | SYMBOL | 25 | FOXP3 | 49 | OSM |

| 2 | APOL1 | 26 | FPR2 | 50 | PDCD6IP |

| 3 | BHLHE40 | 27 | GPX4 | 51 | PGF |

| 4 | BIRC3 | 28 | GZMA | 52 | PKM |

| 5 | BSG | 29 | GZMB | 53 | PLK1 |

| 6 | BST2 | 30 | HMGB1 | 54 | PPARG |

| 7 | BTK | 31 | HSP90AA1 | 55 | PRDM1 |

| 8 | CD14 | 32 | HSP90AB1 | 56 | PTEN |

| 9 | CDKN2B-AS1 | 33 | ICAM1 | 57 | PTGS2 |

| 10 | CEBPB | 34 | IKZF1 | 58 | RBBP7 |

| 11 | CEP55 | 35 | IL18 | 59 | SDHB |

| 12 | CHMP2A | 36 | IL1B | 60 | SEZ6L2 |

| 13 | CHMP2B | 37 | IL1RN | 61 | SUGT1 |

| 14 | CHMP3 | 38 | KCNQ1OT1 | 62 | TCEA3 |

| 15 | CHMP4C | 39 | KIF23 | 63 | TLR2 |

| 16 | CLEC5A | 40 | LY96 | 64 | TREM1 |

| 17 | CTSG | 41 | LYST | 65 | TREM2 |

| 18 | CXCL8 | 42 | MALAT1 | 66 | TRIM31 |

| 19 | CYCS | 43 | MKI67 | 67 | TUBB6 |

| 20 | DNMT1 | 44 | MPEG1 | 68 | TXNIP |

| 21 | DPEP1 | 45 | NAIP | 69 | VCAM1 |

| 22 | EGFR | 46 | NDUFA13 | 70 | VIM |

| 23 | ELAVL1 | 47 | NEAT1 | 71 | VPS4B |

| 24 | EZH2 | 48 | NLRP3 | 72 | ZFAS1 |

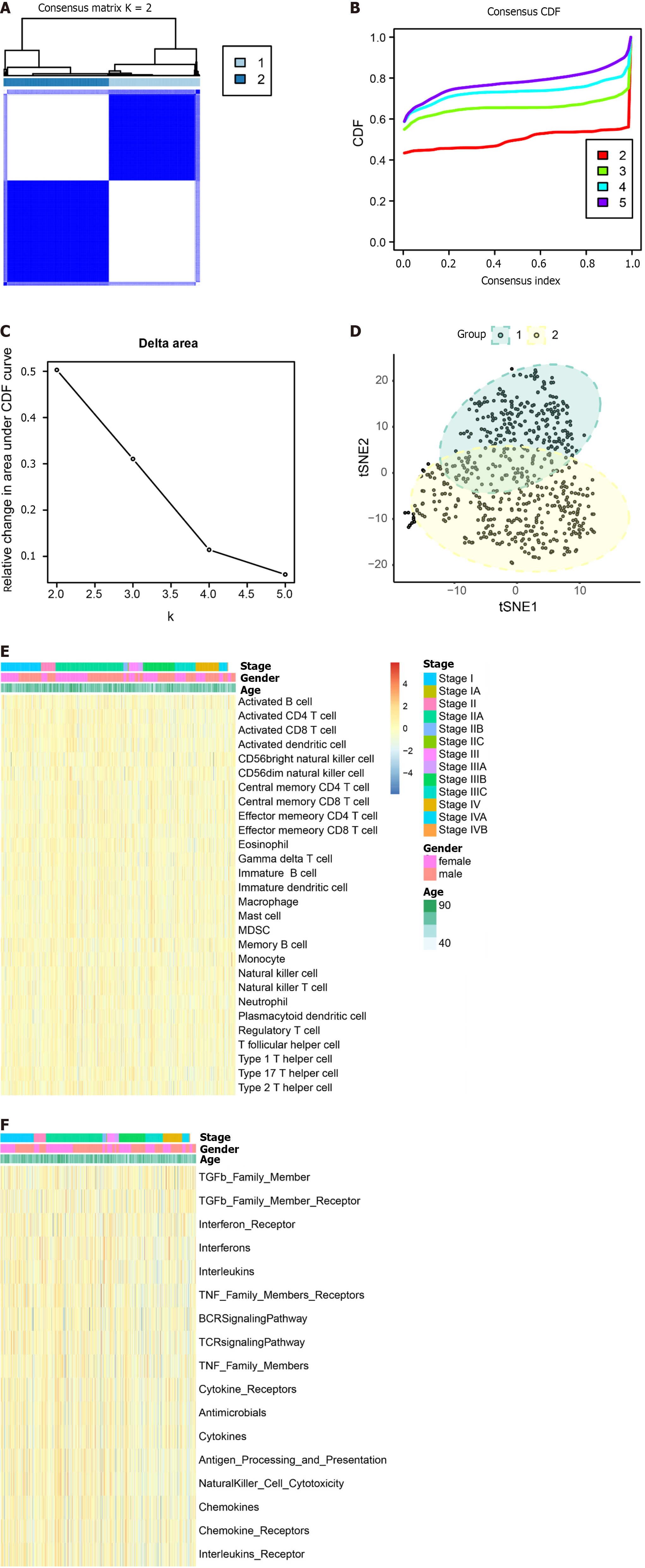

Tumor samples TCGA were subjected to typing through the consensus clustering method. After a thorough evaluation considering the consistency matrix heatmap, cumulative distribution curve, and delta area curve, we determined the cluster number to be 2 (Figure 8A-C). Subsequently, the tSNE algorithm was employed for cluster visualization (Figure 8D). Finally, we conducted single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) with a focus on immune cells (Figure 8E) and immune function (Figure 8F).

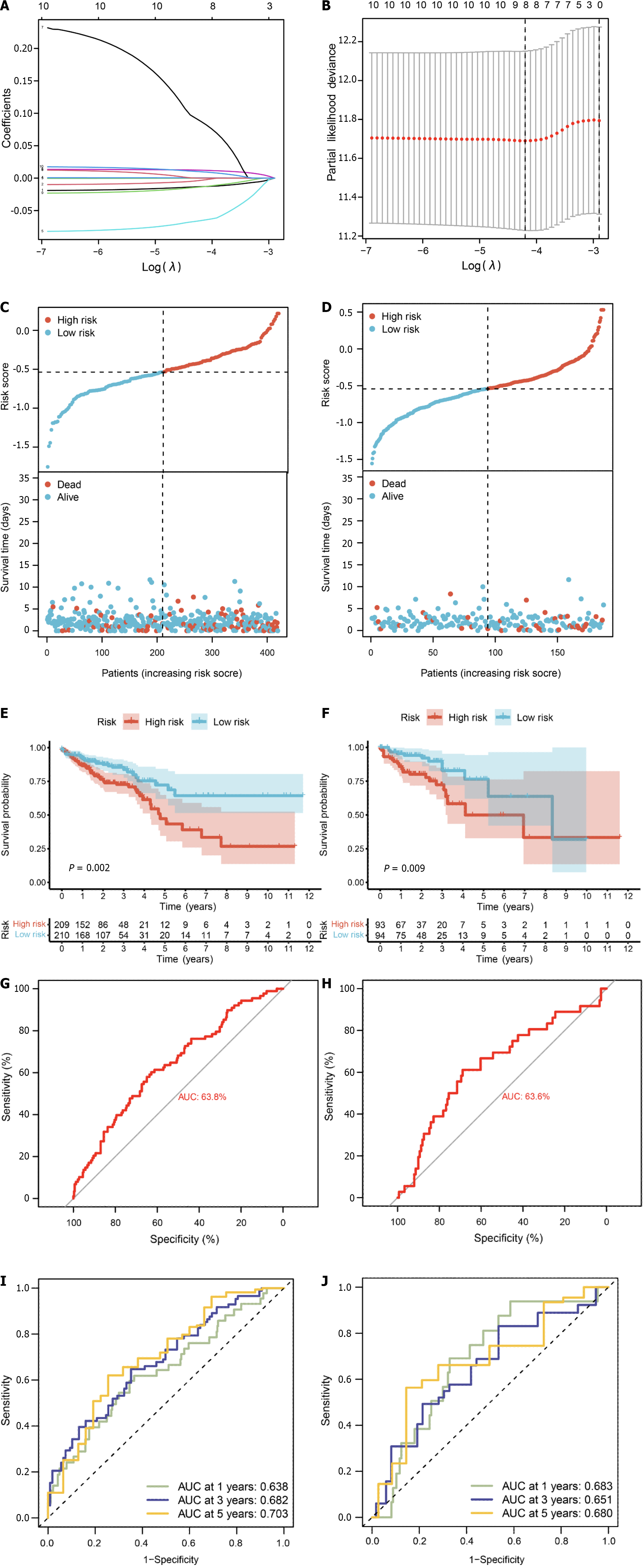

We conducted survival analysis utilizing both single-cell data and TCGA-CRC data, which comprises survival information for 606 samples. In addition to the 71 core genes, we incorporated differential genes specific to single-cell and bulk transcriptomes, resulting in a final set of 178 genes present in the TCGA expression matrix (Supplementary Table 9). Univariate Cox analysis assessed the correlation between these 178 genes and the prognosis of CRC patients, revealing 10 genes significantly correlated with prognosis (P value < 0.05) (Supplementary Table 10). Subsequently, we randomly divided the diseased samples into training and validation sets at a ratio of 7:3. The training set was employed for constructing a prognostic model using LASSO-Cox regression (Figure 9A and B), yielding a risk model composed of 8 genes (CHMP2B, SDHB, BST2, BE2D2, GJA1, AIM2, PDCD6IP, and SEZ6L2). Based on the median value of the risk score, patients were classified into low-risk and high-risk groups. Risk maps and survival states for the training and test sets illustrated an increase in the risk score corresponding to an elevated risk of death and decreased survival time (Figure 9C and D).

To assess prediction accuracy, we performed a ROC analysis. The results indicated a favorable predictive ability of the risk score for OS in CRC patients, with area under curve (AUC) values of 63.8% and 63.6% for the training and validation sets, respectively (Figure 9E and F). Kaplan-Meier curves demonstrated worse OS in patients with high-risk scores compared to those with low-risk scores (P < 0.05, Figure 9G and H). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year AUCs of risk scores based on the prognostic models were all above 0.6 (Figure 9I and J).

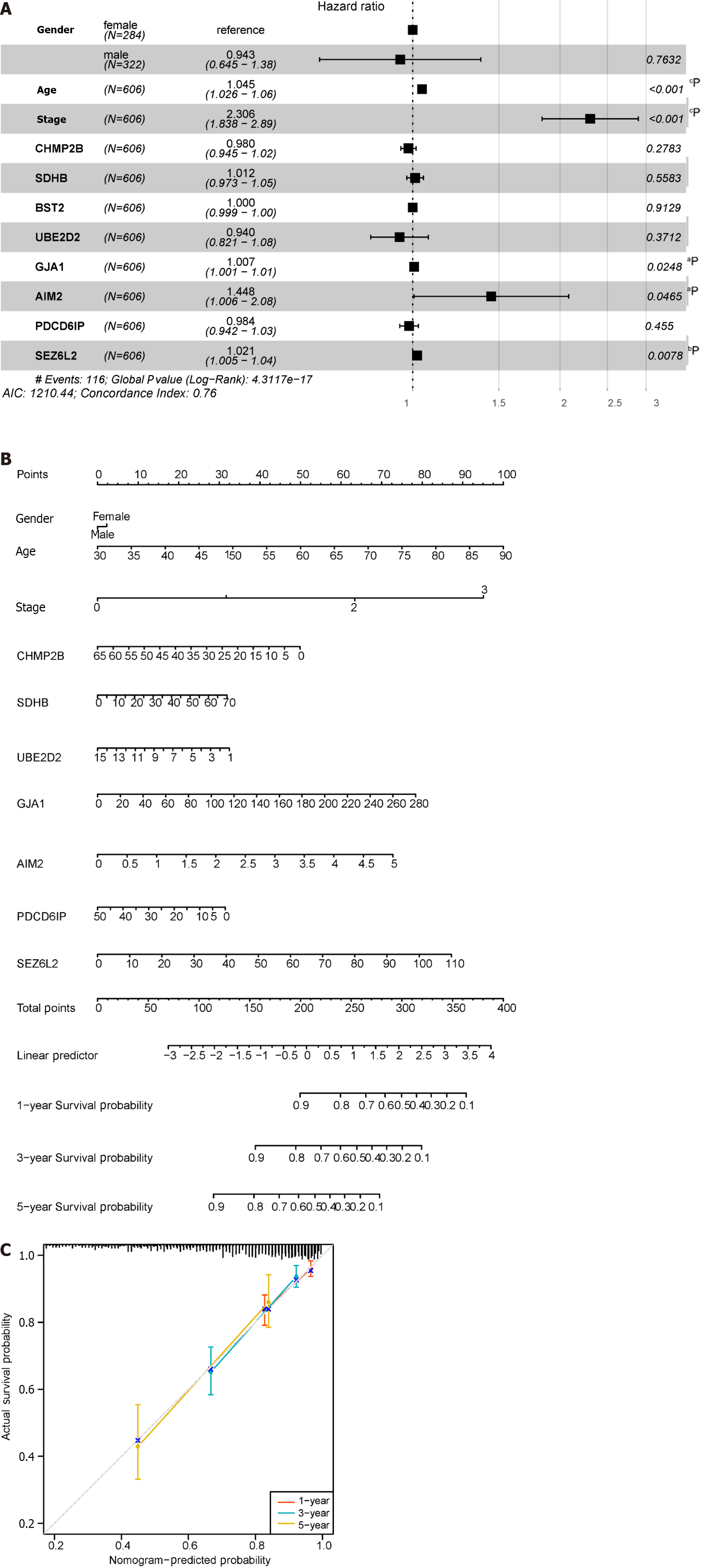

The forest plot (Figure 10A) highlighted strong correlations with clinicopathological features, particularly tumor stage. Additionally, by leveraging clinical data within the dataset, we observed a correlation between pyroptosis-related genes and the age of tumors, with no significant association with gender. Subsequently, by integrating clinicopathological characteristics, a nomogram (Figure 10B) was developed to predict survival probability. The calibration curve indicated accurate results (Figure 10C).

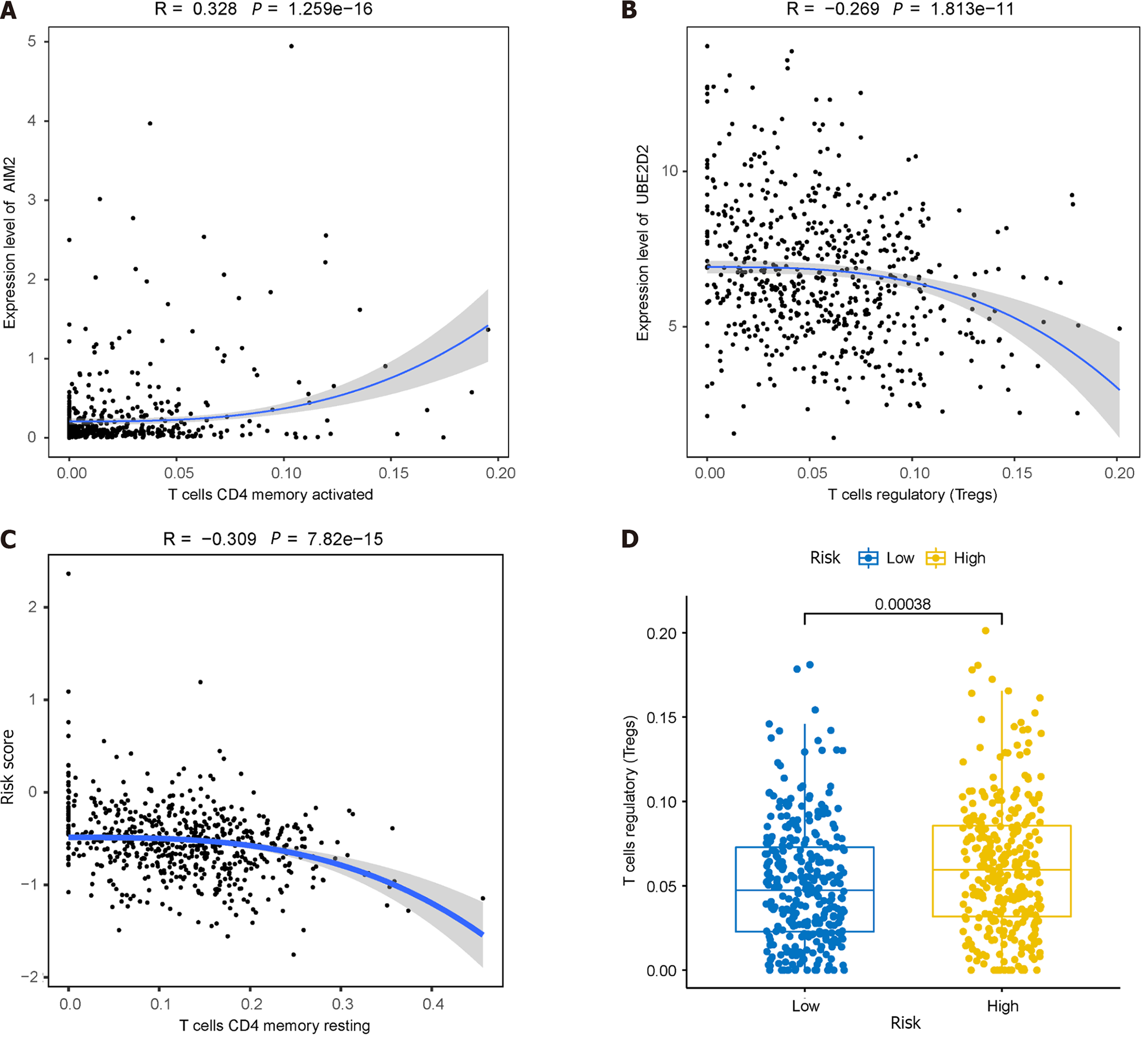

Given the significantly lower survival rate in the high-risk group based on the previous results, we explored potential differences in immune infiltration between the two risk groups. The CIBERSORTx algorithm was employed to calculate immune infiltration in CRC samples from TCGA. The scatterplot depicted correlations between the expression of prognostic genes and immune infiltration in CRC. AIM2 expression showed a positive correlation with the cellular abundance of activated memory CD4+ T cells, while UBE2D2 expression exhibited a negative correlation with the cellular abundance of Tregs (Figure 11A and B). The risk score demonstrated a negative correlation with the cellular abundance of resting memory CD4+ T cells (Figure 11C). Additionally, a significant difference in the abundance of Tregs was observed between the high and low-risk groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 11D).

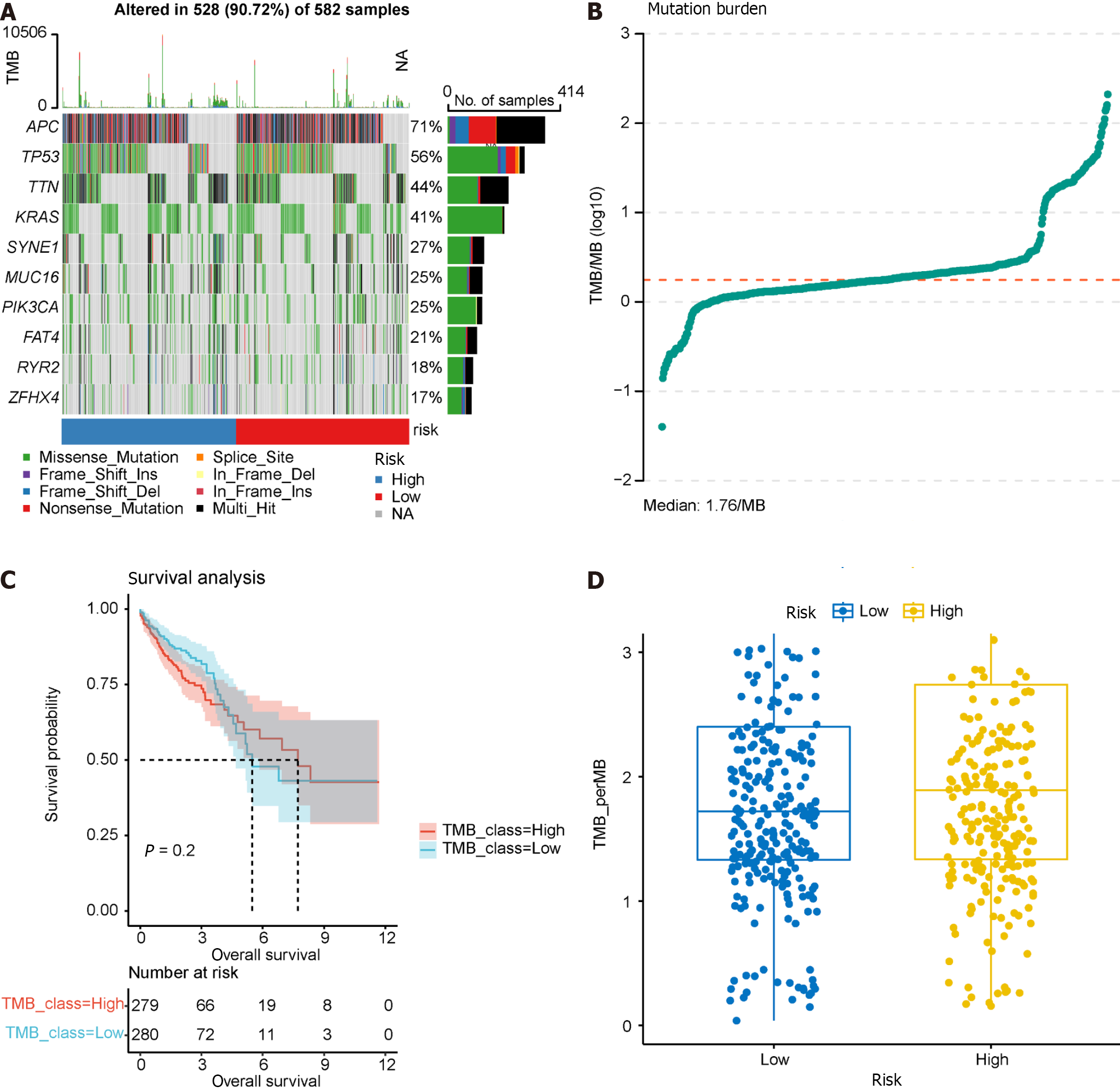

TMB serves as a predictor of immunotherapy response, and we calculated TMB using “maf” files, investigating the relationship between the model groupings and TMB. Waterfall charts were generated for the top 10 frequently mutated genes, revealing common somatic mutation genes such as APC and TP53 in CRC (Figure 12A). TMB was calculated and visualized, with a median TMB of 1.78/Mb (Figure 12B). Subsequently, we explored the impact of TMB on survival (Figure 12C), revealing that TMB had minimal effect on survival in this dataset. Furthermore, no significant difference was observed in TMB between the high- and low-risk groups in the prognostic model (Figure 12D), suggesting that incorporating TMB into the prognostic model for this dataset may not be necessary. Additional studies on the effect of TMB on prognosis may be warranted.

We determined the expression of 8 prognostic genes in CRC samples using TCGA-COADREAD data in the UCSC database. Among them, 7 genes were shown differentially expressed in CRC samples and normal samples. The result showed that CHMP2B, SDHB, UBE2D2, AIM2, PDCD6IP, and SEZ6L2 were significantly up-regulated in CRC samples while GJA1 was significantly down-regulated. No significant expression difference was found between normal and tumor samples for BST2 (Figure 13).

Several studies have shown that pyroptosis plays a crucial role in tumor growth[17-19,45]. It affects prognosis by changing the immune microenvironment and is linked to the effectiveness of immunotherapy[46], Consequently, it has been utilized in building prognostic models for various cancers[21,47,48]. However, most of these studies utilized bulk RNA sequencing, whereas scRNA-seq is more advantageous for investigating cancer prognostic models and the immune microenvironment at a single-cell resolution level[49-51]. Recognizing the pivotal role of pyroptosis in cancers and the unfavorable prognosis of CRC, we developed a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for CRC using the scRNA-seq method. Notably, this is the initial study applying scRNA-seq technology to identify pyroptosis-related genes for constructing CRC prognostic prediction models and exploring the relationship between pyroptosis-related genes and immune infiltration.

By integrating single-cell transcriptome and bulk transcriptome data, we identified 178 pyroptosis-related DEGs from CRC samples. Subsequently, utilizing univariate COX analysis and the LASSO-Cox regression algorithm, we established a risk model comprising 8 pyroptosis-related genes: CHMP2B, SDHB, BST2, UBE2D2, GJA1, AIM2, PDCD

Among the 8 genes, SDHB serves as the catalytic core component of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH), a mitochondrial metabolic enzyme[52]. Mutations in SDHB result in enzyme dysfunction associated with cancer development[52-54]. Wang et al[52] observed that SDHB influences CRC invasion and metastasis through the TGF-β pathway. BST2 (bone marrow stromal antigen 2) is a protein-coding gene overexpressed in several cancers[55]. Chiang et al[56] identified BST2 as a biomarker and prognosticator for CRC[56]. UBE2D2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes E2), associated with hypoxia, prevents the degradation of HIF1α and 2α by proteasome systems. Lee et al[57] reported that UBE2D2 could predict the OS of CRC. GJA1 (gap junction alpha-1), a member of the GJ family, is the predominant one expressed in epithelial tissues. Hu et al[58] demonstrated that GJA1 serves as a prognostic biomarker for CRC. AIM2, an inflammasome sensor, provides cytokine-independent protection, influencing CRC[59]. SEZ6L2 (seizure-related 6 homolog/mouse-like 2) of the SEZ6 family is identified as a potential prognosis biomarker and therapy target for CRC[60]. The six pyroptosis-related genes above have demonstrated potential impacts on CRC prognosis, aligning with our findings. Notably, the existing prognostic models for these genes relied on bulk RNA sequencing and focused solely on whole tumor cells. In our study, risk models were validated at both bulk RNA and single-cell levels. Regarding CHMP2B and PDCD6IP, their roles in pyroptosis have not been fully explored. We are the first to identify these two genes as potential prognostic biomarkers for CRC.

Immune cells within the TME play a pivotal role in influencing the tumor process[61]. Pyroptosis has been demon

We explored the relationship between the expression of pyroptosis-related genes and clinical data in CRC using the TCGA dataset. Our findings revealed an association between the expression of these genes and patient age and tumor stage, while no correlation was observed with gender.

Furthermore, we delved into the functional roles of pyroptosis in CRC. Functional analyses indicated significant enrichment of pyroptosis-related genes in the regulation of inflammatory responses. Notably, key intermediate factors such as GSDMD, IL-1β, and IL-18, known for their involvement in the pyroptosis process, were identified as contributors to the regulation of inflammatory responses[70]. This underscores our study's demonstration of the regulatory role of pyroptosis in inflammatory responses, thereby impacting tumor progression.

Finally, we validated the differential expression of the eight prognostic genes in CRC and normal samples using TCGA-COADREAD data from the UCSC database. Out of these, seven genes-CHMP2B, SDHB, UBE2D2, GJA1, AIM2, PDCD6IP, and SEZ6L2-showed significant differential expression, with six genes up-regulated and one gene down-regulated. This outcome suggests that these seven pyroptosis-related genes could be potential targets for clinical treatment in CRC. However, further data and validation from clinical trials are required. To advance research in this area, additional experiments involving patients, as well as in vitro and in vivo studies, are currently underway in our laboratory.

Leveraging scRNA-seq analysis, we formulated a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for CRC. This model demonstrates efficacy in predicting prognosis, survival OS, and effectively stratifying risk. The eight pyroptosis-related genes comprising the risk score play crucial roles in regulating inflammatory responses, modulating immune infiltration, and influencing the onset and progression of CRC. The insights derived from this study hold promise for enhancing clinical management and immune therapy strategies for CRC patients.

Pyroptosis impacts the development of malignant tumors, yet its role in colorectal cancer (CRC) prognosis remains uncertain.

To explore the role of pyroptosis in CRC prognosis.

To assess the prognostic significance of pyroptosis-related genes and their association with CRC immune infiltration.

Single-cell sequencing combined with Gene Expression Omnibus database and The Cancer Genome Atlas database.

We constructed a prognostic model and demonstrated that pyroptosis is associated with immune infiltration in CRC.

We developed a pyroptosis-related prognostic model for CRC, affirming its correlation with immune infiltration.

This model may prove useful for CRC prognostic evaluation.

This study is a joint effort of many investigators and staff members, and their contribution is gratefully acknowledged.

| 1. | Ciardiello F, Ciardiello D, Martini G, Napolitano S, Tabernero J, Cervantes A. Clinical management of metastatic colorectal cancer in the era of precision medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:372-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ye C, Deng Y, Sun W, Yuan Y. Editorial: Recent advances of drug resistance research in colorectal cancer therapy. Front Oncol. 2022;12:1059223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Mühlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, Abujamel T, Dogan B, Rogers AB, Rhodes JM, Stintzi A, Simpson KW, Hansen JJ, Keku TO, Fodor AA, Jobin C. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1374] [Cited by in RCA: 1735] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Khan S. Potential role of Escherichia coli DNA mismatch repair proteins in colon cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2015;96:475-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Khan S, Imran A, Khan AA, Abul Kalam M, Alshamsan A. Systems Biology Approaches for the Prediction of Possible Role of Chlamydia pneumoniae Proteins in the Etiology of Lung Cancer. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0148530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Khan S, Zaidi S, Alouffi AS, Hassan I, Imran A, Khan RA. Computational Proteome-Wide Study for the Prediction of Escherichia coli Protein Targeting in Host Cell Organelles and Their Implication in Development of Colon Cancer. ACS Omega. 2020;5:7254-7261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khan S, Zakariah M, Palaniappan S. Computational prediction of Mycoplasma hominis proteins targeting in nucleus of host cell and their implication in prostate cancer etiology. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:10805-10813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Khan S, Zakariah M, Rolfo C, Robrecht L, Palaniappan S. Prediction of mycoplasma hominis proteins targeting in mitochondria and cytoplasm of host cells and their implication in prostate cancer etiology. Oncotarget. 2017;8:30830-30843. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 2083] [Article Influence: 173.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 10. | Ganesh K, Stadler ZK, Cercek A, Mendelsohn RB, Shia J, Segal NH, Diaz LA Jr. Immunotherapy in colorectal cancer: rationale, challenges and potential. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:361-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1114] [Cited by in RCA: 1368] [Article Influence: 195.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sahu A, Kose K, Kraehenbuehl L, Byers C, Holland A, Tembo T, Santella A, Alfonso A, Li M, Cordova M, Gill M, Fox C, Gonzalez S, Kumar P, Wang AW, Kurtansky N, Chandrani P, Yin S, Mehta P, Navarrete-Dechent C, Peterson G, King K, Dusza S, Yang N, Liu S, Phillips W, Guitera P, Rossi A, Halpern A, Deng L, Pulitzer M, Marghoob A, Chen CJ, Merghoub T, Rajadhyaksha M. In vivo tumor immune microenvironment phenotypes correlate with inflammation and vasculature to predict immunotherapy response. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu J, Dai S, Jiang K, Xiao Q, Yuan Y, Ding K. Combining single-cell sequencing to identify key immune genes and construct the prognostic evaluation model for colon cancer patients. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11:e465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Tepus M, Yau TO. Non-Invasive Colorectal Cancer Screening: An Overview. Gastrointest Tumors. 2020;7:62-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Xu MD, Qi P, Du X. Long non-coding RNAs in colorectal cancer: implications for pathogenesis and clinical application. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:1310-1320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Diehl D, Hessel E, Oesterle D, Renner-Müller I, Elmlinger M, Langhammer M, Göttlicher M, Wolf E, Lahm H, Hoeflich A. IGFBP-2 overexpression reduces the appearance of dysplastic aberrant crypt foci and inhibits growth of adenomas in chemically induced colorectal carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:2220-2225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C, Chen X. Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 996] [Cited by in RCA: 1638] [Article Influence: 327.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou B, Zhang JY, Liu XS, Chen HZ, Ai YL, Cheng K, Sun RY, Zhou D, Han J, Wu Q. Tom20 senses iron-activated ROS signaling to promote melanoma cell pyroptosis. Cell Res. 2018;28:1171-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 508] [Article Influence: 63.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hu J, Pei W, Jiang M, Huang Y, Dong F, Jiang Z, Xu Y, Li Z. DFNA5 regulates immune cells infiltration and exhaustion. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22:107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Molina-Crespo Á, Cadete A, Sarrio D, Gámez-Chiachio M, Martinez L, Chao K, Olivera A, Gonella A, Díaz E, Palacios J, Dhal PK, Besev M, Rodríguez-Serrano M, García Bermejo ML, Triviño JC, Cano A, García-Fuentes M, Herzberg O, Torres D, Alonso MJ, Moreno-Bueno G. Intracellular Delivery of an Antibody Targeting Gasdermin-B Reduces HER2 Breast Cancer Aggressiveness. Clin Cancer Res. 2019;25:4846-4858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ye Y, Dai Q, Qi H. A novel defined pyroptosis-related gene signature for predicting the prognosis of ovarian cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 332] [Article Influence: 66.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shao W, Yang Z, Fu Y, Zheng L, Liu F, Chai L, Jia J. The Pyroptosis-Related Signature Predicts Prognosis and Indicates Immune Microenvironment Infiltration in Gastric Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:676485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Zhang Q, Tan Y, Zhang J, Shi Y, Qi J, Zou D, Ci W. Pyroptosis-Related Signature Predicts Prognosis and Immunotherapy Efficacy in Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Front Immunol. 2022;13:782982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lei Y, Tang R, Xu J, Wang W, Zhang B, Liu J, Yu X, Shi S. Applications of single-cell sequencing in cancer research: progress and perspectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2021;14:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 408] [Article Influence: 81.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Abrams D, Kumar P, Karuturi RKM, George J. A computational method to aid the design and analysis of single cell RNA-seq experiments for cell type identification. BMC Bioinformatics. 2019;20:275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bartoschek M, Oskolkov N, Bocci M, Lövrot J, Larsson C, Sommarin M, Madsen CD, Lindgren D, Pekar G, Karlsson G, Ringnér M, Bergh J, Björklund Å, Pietras K. Spatially and functionally distinct subclasses of breast cancer-associated fibroblasts revealed by single cell RNA sequencing. Nat Commun. 2018;9:5150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 639] [Article Influence: 79.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim C, Gao R, Sei E, Brandt R, Hartman J, Hatschek T, Crosetto N, Foukakis T, Navin NE. Chemoresistance Evolution in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Delineated by Single-Cell Sequencing. Cell. 2018;173:879-893.e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 756] [Cited by in RCA: 770] [Article Influence: 96.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhang L, Li Z, Skrzypczynska KM, Fang Q, Zhang W, O'Brien SA, He Y, Wang L, Zhang Q, Kim A, Gao R, Orf J, Wang T, Sawant D, Kang J, Bhatt D, Lu D, Li CM, Rapaport AS, Perez K, Ye Y, Wang S, Hu X, Ren X, Ouyang W, Shen Z, Egen JG, Zhang Z, Yu X. Single-Cell Analyses Inform Mechanisms of Myeloid-Targeted Therapies in Colon Cancer. Cell. 2020;181:442-459.e29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 1040] [Article Influence: 173.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 28. | Pelka K, Hofree M, Chen JH, Sarkizova S, Pirl JD, Jorgji V, Bejnood A, Dionne D, Ge WH, Xu KH, Chao SX, Zollinger DR, Lieb DJ, Reeves JW, Fuhrman CA, Hoang ML, Delorey T, Nguyen LT, Waldman J, Klapholz M, Wakiro I, Cohen O, Albers J, Smillie CS, Cuoco MS, Wu J, Su MJ, Yeung J, Vijaykumar B, Magnuson AM, Asinovski N, Moll T, Goder-Reiser MN, Applebaum AS, Brais LK, DelloStritto LK, Denning SL, Phillips ST, Hill EK, Meehan JK, Frederick DT, Sharova T, Kanodia A, Todres EZ, Jané-Valbuena J, Biton M, Izar B, Lambden CD, Clancy TE, Bleday R, Melnitchouk N, Irani J, Kunitake H, Berger DL, Srivastava A, Hornick JL, Ogino S, Rotem A, Vigneau S, Johnson BE, Corcoran RB, Sharpe AH, Kuchroo VK, Ng K, Giannakis M, Nieman LT, Boland GM, Aguirre AJ, Anderson AC, Rozenblatt-Rosen O, Regev A, Hacohen N. Spatially organized multicellular immune hubs in human colorectal cancer. Cell. 2021;184:4734-4752.e20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 476] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 110.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Satija R, Farrell JA, Gennert D, Schier AF, Regev A. Spatial reconstruction of single-cell gene expression data. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:495-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2637] [Cited by in RCA: 4746] [Article Influence: 431.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim S, Kang D, Huo Z, Park Y, Tseng GC. Meta-analytic principal component analysis in integrative omics application. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1321-1328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aran D, Looney AP, Liu L, Wu E, Fong V, Hsu A, Chak S, Naikawadi RP, Wolters PJ, Abate AR, Butte AJ, Bhattacharya M. Reference-based analysis of lung single-cell sequencing reveals a transitional profibrotic macrophage. Nat Immunol. 2019;20:163-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1097] [Cited by in RCA: 3291] [Article Influence: 470.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Safran M, Dalah I, Alexander J, Rosen N, Iny Stein T, Shmoish M, Nativ N, Bahir I, Doniger T, Krug H, Sirota-Madi A, Olender T, Golan Y, Stelzer G, Harel A, Lancet D. GeneCards Version 3: the human gene integrator. Database (Oxford). 2010;2010:baq020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 718] [Cited by in RCA: 1400] [Article Influence: 87.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jin S, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Zhang L, Chang I, Ramos R, Kuan CH, Myung P, Plikus MV, Nie Q. Inference and analysis of cell-cell communication using CellChat. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3052] [Cited by in RCA: 5184] [Article Influence: 1036.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, Ghandi M, Mesirov JP, Tamayo P. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4238] [Cited by in RCA: 9502] [Article Influence: 863.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16184] [Cited by in RCA: 28257] [Article Influence: 2568.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, Newman AM, Alizadeh AA. Profiling Tumor Infiltrating Immune Cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1711:243-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 993] [Cited by in RCA: 2753] [Article Influence: 344.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Steen CB, Liu CL, Alizadeh AA, Newman AM. Profiling Cell Type Abundance and Expression in Bulk Tissues with CIBERSORTx. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2117:135-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 374] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Langfelder P, Horvath S. WGCNA: an R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10254] [Cited by in RCA: 18006] [Article Influence: 1000.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yin Y, Wu S, Niu L, Huang S. A ZFP42/MARK2 regulatory network reduces the damage of retinal ganglion cells in glaucoma: a study based on GEO dataset and in vitro experiments. Apoptosis. 2022;27:1049-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34752] [Cited by in RCA: 63753] [Article Influence: 5795.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 41. | The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D330-D338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2608] [Cited by in RCA: 3220] [Article Influence: 460.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wilkerson MD, Hayes DN. ConsensusClusterPlus: a class discovery tool with confidence assessments and item tracking. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1572-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1686] [Cited by in RCA: 4111] [Article Influence: 256.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jardim DL, Goodman A, de Melo Gagliato D, Kurzrock R. The Challenges of Tumor Mutational Burden as an Immunotherapy Biomarker. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:154-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 870] [Article Influence: 174.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Qi J, Sun H, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Xun Z, Li Z, Ding X, Bao R, Hong L, Jia W, Fang F, Liu H, Chen L, Zhong J, Zou D, Liu L, Han L, Ginhoux F, Liu Y, Ye Y, Su B. Single-cell and spatial analysis reveal interaction of FAP(+) fibroblasts and SPP1(+) macrophages in colorectal cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13:1742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 603] [Article Influence: 150.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Cheng Z, Han J, Jiang F, Chen W, Ma X. Prognostic pyroptosis-related lncRNA signature predicts the efficacy of immunotherapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2022;32:101389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Li L, Jiang M, Qi L, Wu Y, Song D, Gan J, Li Y, Bai Y. Pyroptosis, a new bridge to tumor immunity. Cancer Sci. 2021;112:3979-3994. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Song J, Sun Y, Cao H, Liu Z, Xi L, Dong C, Yang R, Shi Y. A novel pyroptosis-related lncRNA signature for prognostic prediction in patients with lung adenocarcinoma. Bioengineered. 2021;12:5932-5949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Fu XW, Song CQ. Identification and Validation of Pyroptosis-Related Gene Signature to Predict Prognosis and Reveal Immune Infiltration in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:748039. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Wang Z, Guo X, Gao L, Wang Y, Ma W, Xing B. Glioblastoma cell differentiation trajectory predicts the immunotherapy response and overall survival of patients. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:18297-18321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Zheng H, Liu H, Ge Y, Wang X. Integrated single-cell and bulk RNA sequencing analysis identifies a cancer associated fibroblast-related signature for predicting prognosis and therapeutic responses in colorectal cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lim B, Lin Y, Navin N. Advancing Cancer Research and Medicine with Single-Cell Genomics. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:456-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Wang H, Chen Y, Wu G. SDHB deficiency promotes TGFβ-mediated invasion and metastasis of colorectal cancer through transcriptional repression complex SNAIL1-SMAD3/4. Transl Oncol. 2016;9:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Hoekstra AS, de Graaff MA, Briaire-de Bruijn IH, Ras C, Seifar RM, van Minderhout I, Cornelisse CJ, Hogendoorn PC, Breuning MH, Suijker J, Korpershoek E, Kunst HP, Frizzell N, Devilee P, Bayley JP, Bovée JV. Inactivation of SDH and FH cause loss of 5hmC and increased H3K9me3 in paraganglioma/pheochromocytoma and smooth muscle tumors. Oncotarget. 2015;6:38777-38788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Hao HX, Khalimonchuk O, Schraders M, Dephoure N, Bayley JP, Kunst H, Devilee P, Cremers CW, Schiffman JD, Bentz BG, Gygi SP, Winge DR, Kremer H, Rutter J. SDH5, a gene required for flavination of succinate dehydrogenase, is mutated in paraganglioma. Science. 2009;325:1139-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 553] [Cited by in RCA: 551] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Cai D, Cao J, Li Z, Zheng X, Yao Y, Li W, Yuan Z. Up-regulation of bone marrow stromal protein 2 (BST2) in breast cancer with bone metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Chiang SF, Kan CY, Hsiao YC, Tang R, Hsieh LL, Chiang JM, Tsai WS, Yeh CY, Hsieh PS, Liang Y, Chen JS, Yu JS. Bone Marrow Stromal Antigen 2 Is a Novel Plasma Biomarker and Prognosticator for Colorectal Carcinoma: A Secretome-Based Verification Study. Dis Markers. 2015;2015:874054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lee JH, Jung S, Park WS, Choe EK, Kim E, Shin R, Heo SC, Lee JH, Kim K, Chai YJ. Prognostic nomogram of hypoxia-related genes predicting overall survival of colorectal cancer-Analysis of TCGA database. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hu W, Li S, Zhang S, Xie B, Zheng M, Sun J, Yang X, Zang L. GJA1 is a Prognostic Biomarker and Correlated with Immune Infiltrates in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:11649-11661. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Sharma BR, Kanneganti TD. Inflammasome signaling in colorectal cancer. Transl Res. 2023;252:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | An N, Zhao Y, Lan H, Zhang M, Yin Y, Yi C. SEZ6L2 knockdown impairs tumour growth by promoting caspase-dependent apoptosis in colorectal cancer. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:4223-4232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lei X, Lei Y, Li JK, Du WX, Li RG, Yang J, Li J, Li F, Tan HB. Immune cells within the tumor microenvironment: Biological functions and roles in cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2020;470:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 1041] [Article Influence: 148.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Chen X, Chen H, Yao H, Zhao K, Zhang Y, He D, Zhu Y, Cheng Y, Liu R, Xu R, Cao K. Turning up the heat on non-immunoreactive tumors: pyroptosis influences the tumor immune microenvironment in bladder cancer. Oncogene. 2021;40:6381-6393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Erkes DA, Cai W, Sanchez IM, Purwin TJ, Rogers C, Field CO, Berger AC, Hartsough EJ, Rodeck U, Alnemri ES, Aplin AE. Mutant BRAF and MEK Inhibitors Regulate the Tumor Immune Microenvironment via Pyroptosis. Cancer Discov. 2020;10:254-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 58.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pagès C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, Zinzindohoué F, Bruneval P, Cugnenc PH, Trajanoski Z, Fridman WH, Pagès F. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960-1964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4318] [Cited by in RCA: 5013] [Article Influence: 250.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (19)] |

| 65. | Prall F, Dührkop T, Weirich V, Ostwald C, Lenz P, Nizze H, Barten M. Prognostic role of CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage III colorectal cancer with and without microsatellite instability. Hum Pathol. 2004;35:808-816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 66. | Laghi L, Bianchi P, Miranda E, Balladore E, Pacetti V, Grizzi F, Allavena P, Torri V, Repici A, Santoro A, Mantovani A, Roncalli M, Malesci A. CD3+ cells at the invasive margin of deeply invading (pT3-T4) colorectal cancer and risk of post-surgical metastasis: a longitudinal study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:877-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Lu H, Sun Y, Zhu Z, Yao J, Xu H, Huang R, Huang B. Pyroptosis is related to immune infiltration and predictive for survival of colon adenocarcinoma patients. Sci Rep. 2022;12:9233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ge P, Wang W, Li L, Zhang G, Gao Z, Tang Z, Dang X, Wu Y. Profiles of immune cell infiltration and immune-related genes in the tumor microenvironment of colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;118:109228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Deng D, Luo X, Zhang S, Xu Z. Immune cell infiltration-associated signature in colon cancer and its prognostic implications. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:19696-19709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Van Opdenbosch N, Lamkanfi M. Caspases in Cell Death, Inflammation, and Disease. Immunity. 2019;50:1352-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 920] [Article Influence: 131.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khan S, India S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang XD