Published online Feb 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i2.83

Peer-review started: July 7, 2019

First decision: August 20, 2019

Revised: November 23, 2019

Accepted: December 19, 2019

Article in press: December 19, 2019

Published online: February 24, 2020

Processing time: 232 Days and 6.8 Hours

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignancy with a high propensity to metastasize. Esophageal metastasis manifesting as dysphagia is rarely reported in the literature and has not to our knowledge been reported prior to the appearance of the primary disease.

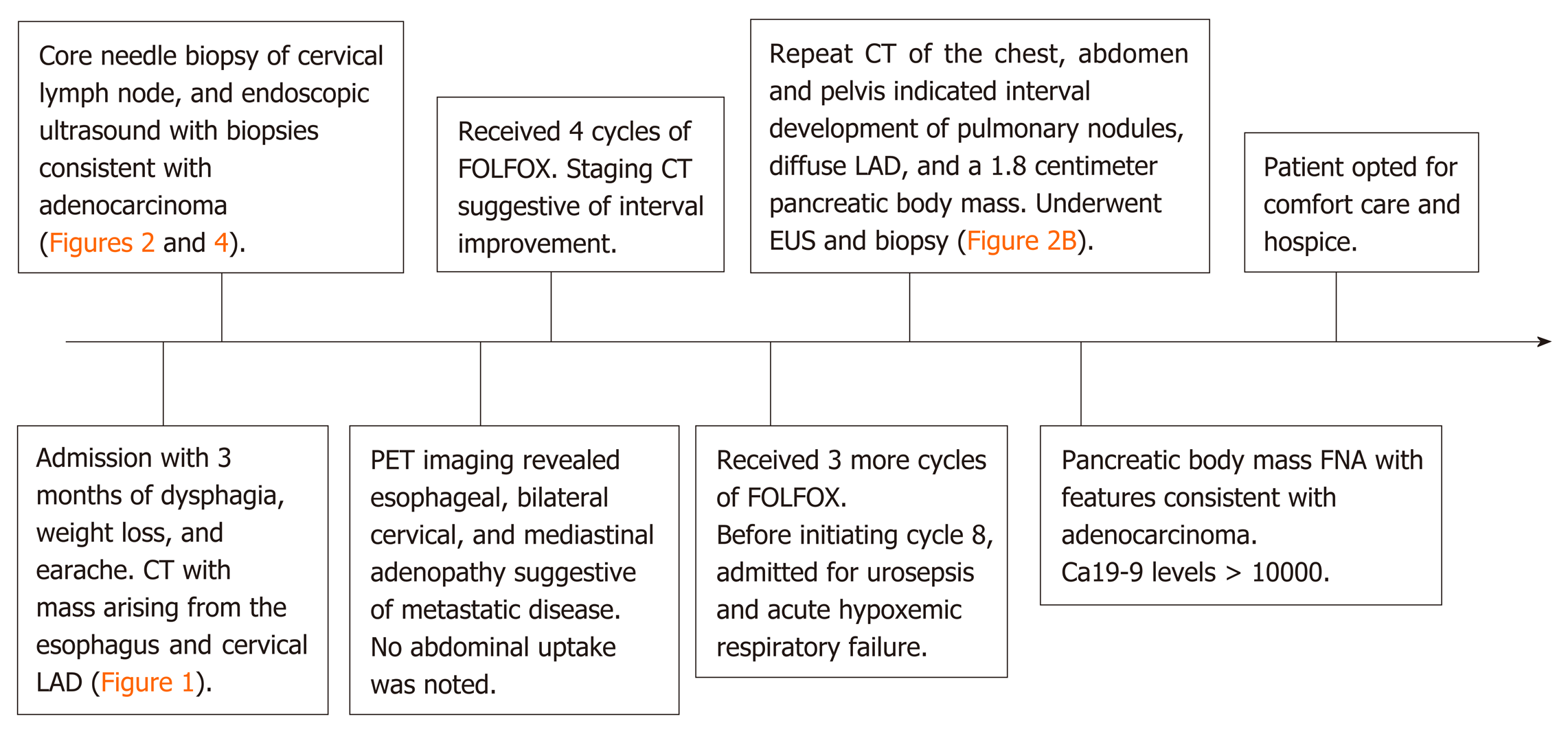

A patient presented with progressive dysphagia to solids and a persistent earache. Computed tomography of the neck and chest revealed a 3.0 cm × 1.8 cm heterogeneous mass originating from the upper third of the esophagus, necrotic cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, and bilateral pulmonary nodules. She underwent a core needle biopsy of a right cervical node, which suggested a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma of unknown primary. She had an upper endoscopy with biopsy of the esophageal mass suggestive of a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. Positron emission tomography imaging revealed increased uptake in the esophageal mass, cervical, and mediastinal lymph nodes. She was started on folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin. Prior to initiation of cycle 8, the patient was found to have a pancreatic body mass that was not present on prior radiographic imaging, confirmed by endoscopic ultrasonography and biopsy to be pancreatic adenocarcinoma. CA19-9 was > 10000 U/mL, suggesting a primary pancreaticobiliary origin.

Esophageal metastasis diagnosed before primary pancreatic adenocarcinoma is rare. This case highlights the profound metastatic potential of pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Core tip: Pancreatic adenocarcinoma is an aggressive malignancy with a high mortality rate and propensity to metastasize. We present a rare case of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma to the esophagus and cervical lymph nodes presenting as dysphagia and an earache months before the primary pancreatic mass was detected on radiographic imaging. This case highlights the highly aggressive nature of pancreatic adenocarcinomas and the metastatic potential early in the disease course. In the setting of metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown primary, clinicians should consider the possibility of a pancreatic origin.

- Citation: Burns EA, Kasparian S, Khan U, Abdelrahim M. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma with early esophageal metastasis: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(2): 83-90

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i2/83.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i2.83

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAC) is an aggressive malignancy that is often locally advanced and widely metastatic by the time symptoms manifest. It is the most common subtype of pancreatic cancer with an increasing incidence, a male predominance, a median age of 71-years-old, and an annual worldwide incidence of 1-10 cases per 100000 people[1]. It is the 4th leading cause of death from cancer in men and women, and is the 3rd leading cause of death due to solid tumors in the Unites States, with an estimated 5-year survival of 9%[1,2]. The most common sites of metastasis are the liver, peritoneum, lungs, bones, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands, though literature supports evidence of wide spread metastatic disease to many other organs[3].

Cancer can disseminate early in the disease course and can occur years before the primary malignancy is detected. This has been documented in various solid malignancies, including the breast, prostate, lungs, colon, kidneys, and malignant melanomas[4]. The following case illustrates a unique presentation of an earache and dysphagia due to PAC metastases months prior to the development of a primary pancreatic mass.

An 80-year-old female presented to the hospital with dysphagia to solids and a persistent right earache.

The patient’s symptoms started 3-mo ago when she noticed progressive and persistent right ear pain and dysphagia to solids associated with a 10-pound weight loss, fatigue, and generalized malaise. She had no other significant medical or surgical history. She had no history of gastroesophageal reflux, alcohol use, tobacco use, or family history of cancer.

The patient has no past medical history.

Vitals on admission were within normal variation, and physical exam was significant for bilateral supraclavicular lymphadenopathy.

Labs indicated a mild neutrophilic leukocytosis and normocytic anemia. Blood biochemistries, coagulation times including prothrombin, partial thromboplastin, and international normalized ratio, and electrocardiogram were within normal limits.

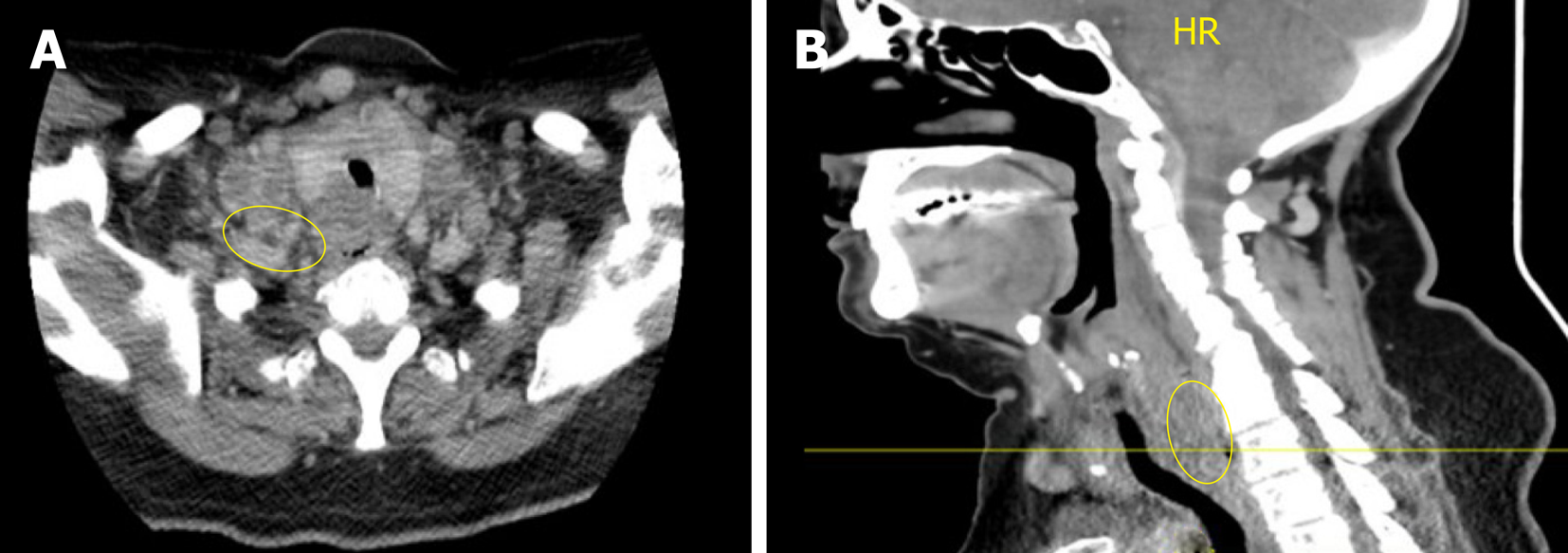

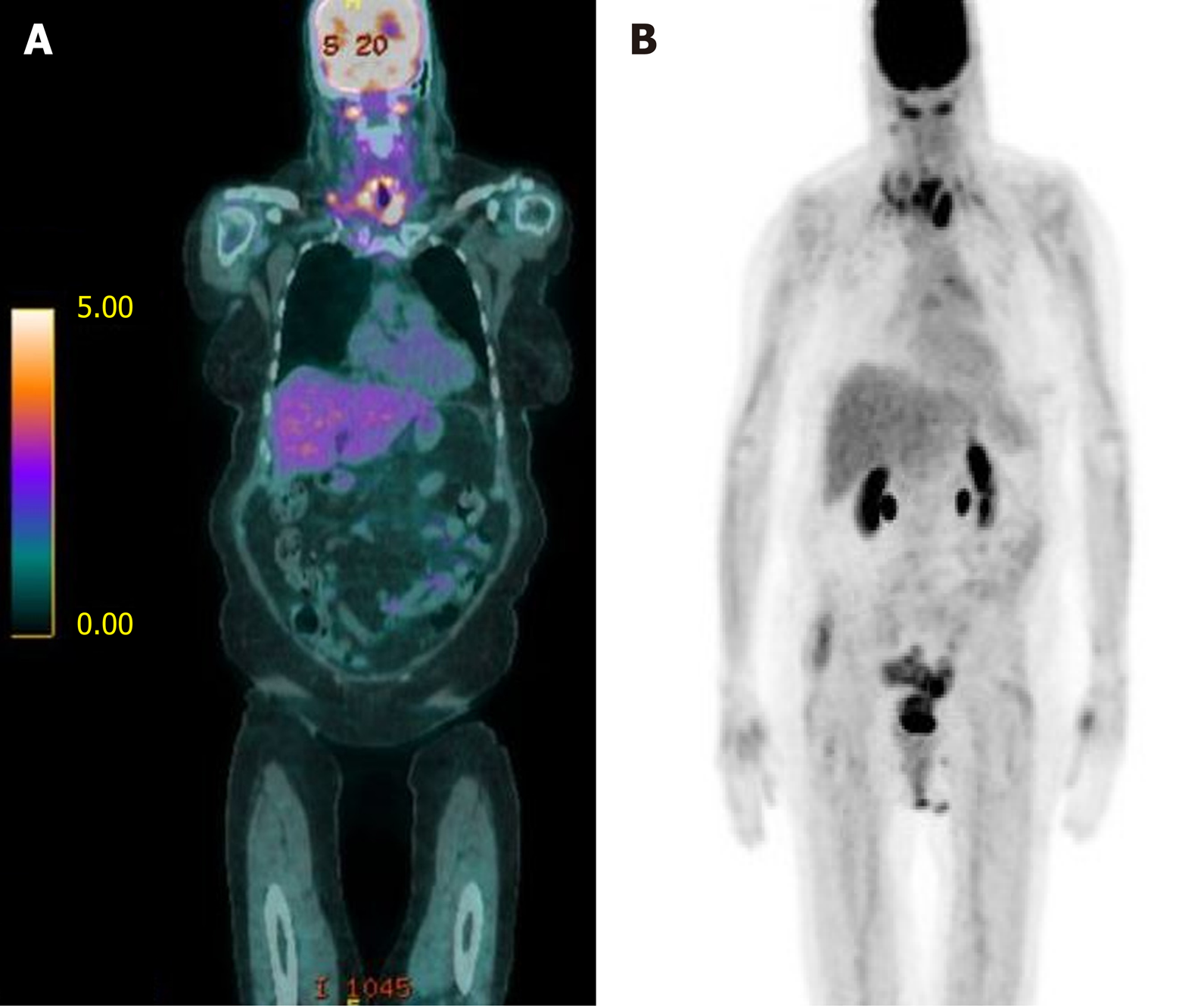

Computed tomography (CT) of the neck and chest revealed a 3.0 cm × 1.8 cm heterogeneous mass originating from the upper third of the esophagus that extended into the superior mediastinum, necrotic cervical and supraclavicular lymphadenopathy, and bilateral pulmonary nodules (Figure 1). Positron emission tomography (PET) imaging revealed an upper esophageal mass (SUV of 6.7), as well as bilateral lower cervical (SUV 5.1) and mediastinal (SUV 3.9) adenopathy consistent with metastatic disease (Figure 2). No abdominal uptake was visualized.

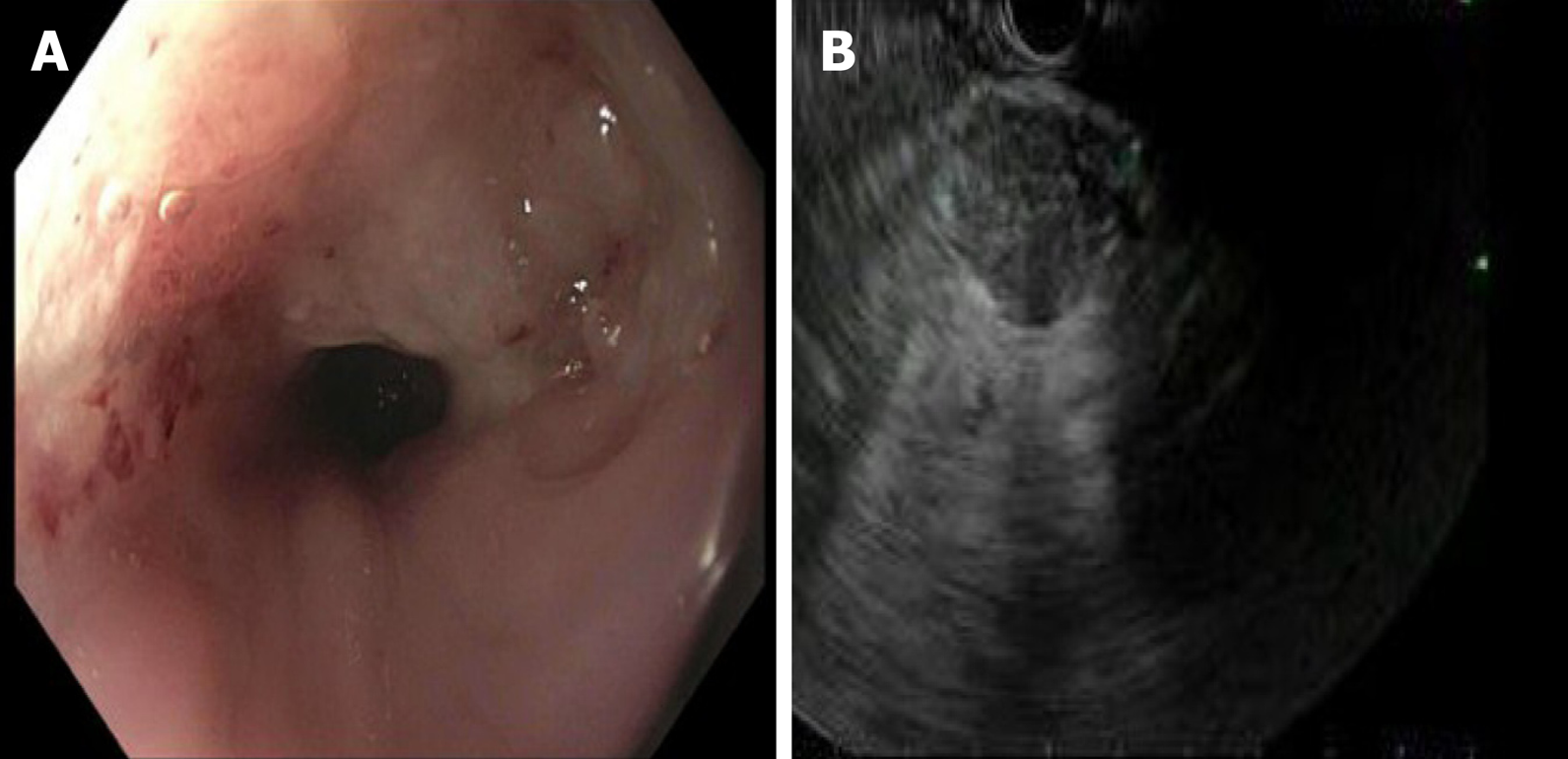

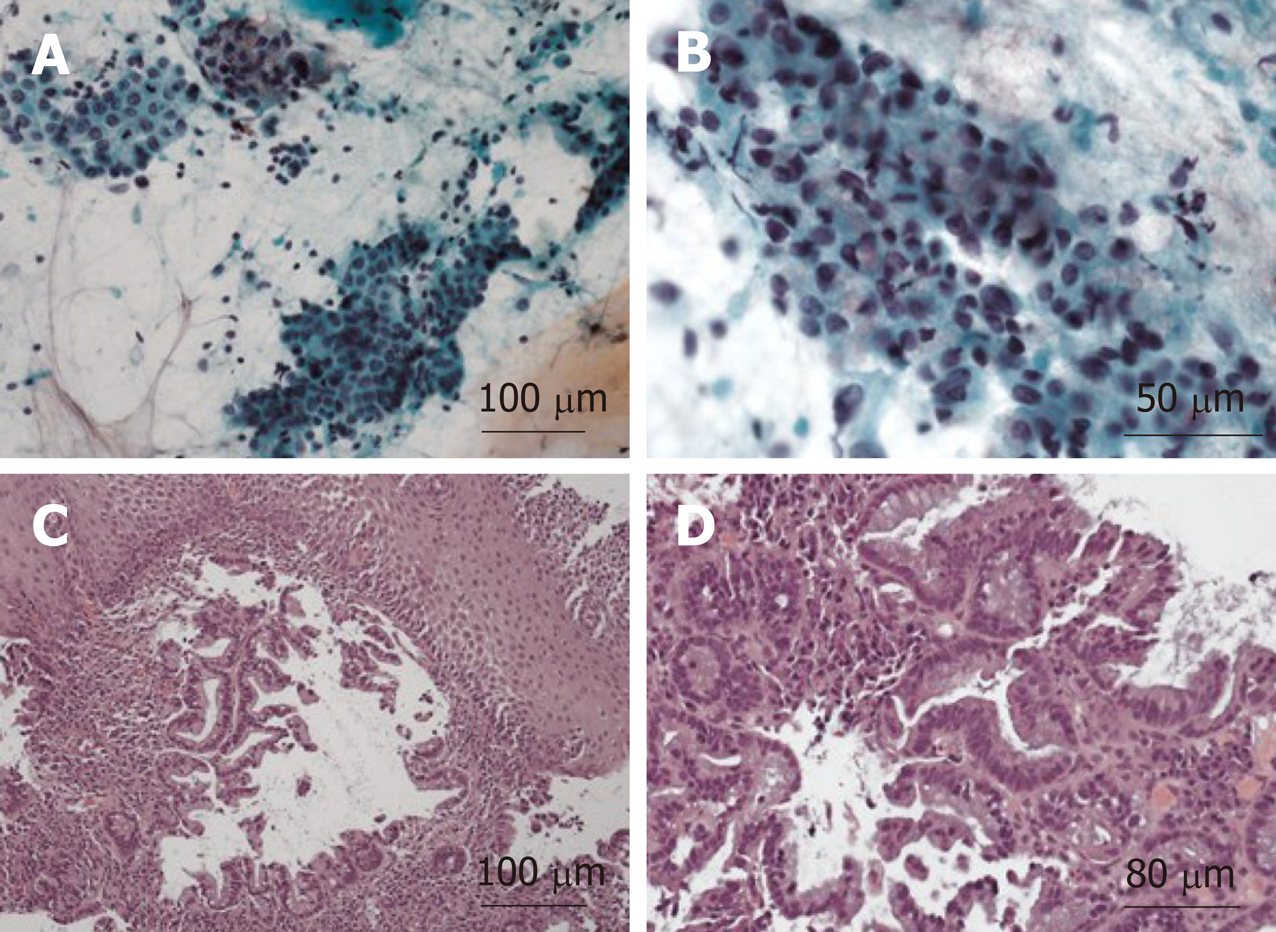

The patient underwent a core needle biopsy of her right cervical node, which demonstrated the presence of malignant mucin secreting glands on a background of extensively fibrotic stroma. Immunohistochemical staining was positive for Caudal Type Homeobox 2 (CDX-2), weakly positive for thyroid transcription factor 1, and HER-2 negative, indicative of an adenocarcinoma. She had an upper endoscopy which demonstrated a mass in the upper third of the esophagus (Figure 3A and B, Figure 4). Biopsies of the esophageal mass demonstrated glandular epithelium, high grade columnar dysplasia with papillary architecture, and nuclear crowding and hyperchromasia with overlying squamous epithelium. Flow cytometry of the esophageal biopsy reported a well-differentiated adenocarcinoma. The patient was initiated on folinic acid, fluorouracil, and oxaliplatin (FOLFOX) since the primary site of the malignancy was unknown. Repeat radiographic staging after 4 cycles of FOLFOX with CT scan of the neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated improvement of her primary mass and lymphadenopathy. Prior to initiation of cycle 8, the patient was hospitalized for significant dehydration and hypotension secondary to urosepsis. A CT of the abdomen and pelvis was concerning for new bibasilar pulmonary nodules, bilateral effusions, and a 1.8-centimeter mass in the body of the pancreas not previously seen on CT or PET imaging (Figure 4). CT of the chest further demonstrated bilateral supraclavicular, subcarinal, and subhilar lymphadenopathy concerning for disease progression. She underwent fine needle aspiration of a left cervical lymph node that yielded cytologic features consistent with adenocarcinoma (Figure 4). Flow cytometry of her pleural fluid also indicated metastatic adenocarcinoma. An endoscopic ultrasound with biopsy of her pancreatic body mass demonstrated infiltrating glands with cytologic atypia and abundant intracytoplasmic mucin with an associated desmoplastic stromal reaction, indicative of a well to moderately differentiated PAC (Figure 2B). There was no loss of normal mismatch repair expression, and absent PD-L1 expression. Her CA 19-9 was > 10000 U/mL, CA 125 was 309 U/mL, and CEA was 71.6 ng/mL, suggestive of a pancreaticobiliary origin of the metastatic adenocarcinoma.

Ultimately, the primary etiology was suspected to be metastatic adenocarcinoma arising from the pancreatic body (Stage 4, T2N2M1).

The patient received 7 cycles of FOLFOX with initial interval improvement in metastatic disease. Before cycle 8 was initiated, she was noted to have disease progression. She opted for comfort care and hospice prior to initiation of alternative chemotherapy (Figure 5).

After noting disease progression, the patient and her family chose to focus on quality of life rather than pursuing further treatment and opted for hospice care. She passed away 11 mo after her initial presentation.

PAC has the capability to metastasize early in the disease course and present with symptoms related to locally or systemically advanced disease, posing a significant treatment obstacle that ultimately contributes to its high mortality rate. Carcinogenesis of PAC follows a series of stepwise mutations causing the normal mucosa to transform into an invasive malignancy[5]. It can be divided into three phases: Acquisition of driver mutations, clonal expansion, and introduction into local and distant microenvironments[6]. The three most frequently described malignant precursors include pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia, mucinous cystic neoplasms, and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms[5]. PanIN is the most common precursor in PAC[5] and is most commonly associated with KRAS oncogene activation, which has been estimated to occur in up to 90% of PAC[7]. KRAS activation leads to uncontrollable cellular proliferation leading to clonal expansion. This often results in additional mutations in progeny cells, including the inactivation of tumor suppressor genes cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A, TP53, and SMAD4, the latter being associated with metastatic disease rather than tumor formation[8]. In sum, the time from the acquisition of the original driver mutations to the birth of the non-metastatic parental cell takes approximately 10 years, with at least 5 more years to acquire metastatic capabilities[9]. During the process of carcinogenesis, a subpopulation of cells can invade through the basement membrane and disseminate into the stroma and bloodstream[9]. However, cancer cells do not necessarily have to follow a pre-conceived dogma, and mouse models have demonstrated that dissemination can occur early in carcinogenesis, especially to sites of inflammation[10]. Though most of these cells do not survive[11], very few surviving cells are needed to establish metastasis[12], and it is possible that these cells become fully malignant prior to the primary tumor site invading into the pancreatic stroma. This unique case demonstrated the presence of metastatic disease that manifested prior to the presence of radiographically significant primary pancreatic disease on CT or PET imaging. A pancreatic mass was not present until 6 mo after the initial diagnosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma of unknown primary, which may indicate a profound metastatic potential very early in tumor carcinogenesis.

Tumors arising from the body of the pancreas are uncommon, accounting for one-third of pancreatic neoplasms[13]. Ductal carcinoma is the most common subtype, which often presents late in the disease course[13] due to absence of biliary obstruction. By the time the mass is recognized on either physical exam or imaging, local infiltration, metastasis to regional lymph nodes, or hematogenous spread to distant organs has often begun[14,15]. The initial presentation of metastatic disease in the absence of imaging characteristics of PAC is uncommon. Ear pain is an atypical initial symptom of pancreatic cancer and was likely a result of distant lymphatic metastasis to the cervical lymph nodes. Dysphagia due to esophageal metastasis is a rare but documented symptom of pancreatic cancer that is seldom reported in the literature[16]. It can be one of the earliest manifestations of PAC yet is indicative of advanced metastatic carcinoma[17]. This case demonstrates that even in the absence of a primary pancreatic mass, patients found to have malignant dysphagia with an unknown primary should be monitored for the development of radiographically or clinically evident PAC.

Although CT and PET imaging are utilized in the staging workup, they may not be able detect occult lesions, a possibility in our patient’s case. For CT imaging, sensitivity ranges from between 67%-77% when identifying tumors less than 2 cm[18-20]. The sensitivity of FDG-PET imaging for PAC range from 61%-100%[21,22] but does not improve diagnostic detection of occult primaries when they were unknown[23], as was the case in this patient.

Regardless if a mass was present on this patient’s pancreas on initial presentation, a concurrent primary esophageal adenocarcinoma or metastatic PAC cannot readily be distinguished by radiographic appearance alone. In this uncommon circumstance, the assessment of CA19-9 may be beneficial in clarifying the origin in certain circumstances. CA 19-9 is one of the most validated biomarkers for PAC, and while it can be elevated in both primary esophageal and PAC, levels > 200 U/mL in the presence of a pancreatic mass is virtually diagnostic of a primary pancreatic malignancy[24]. In an analysis of 24 case series, Ballehaninna et al[25] demonstrated that if the diagnostic threshold of CA 19-9 were increased to 1000 U/mL in pancreatic cancer, then the specificity was 99.8%, with a sensitivity of 41%. In a more recent study involving 26 case series, the sensitivity of CA 19-9 ranged from 79%-81% and specificity of 82%-90%[26]. It is unknown if the same specificity applies when using CA 19-9 to differentiate between two gastrointestinal adenocarcinomas of unknown primary. In this case, tumor markers at presentation were not evaluated. However, a CA 19-9 value would not have been diagnostic, nor would it change management in the radiographic absence of a pancreatic lesion using different imaging modalities. In addition, CA 19-9 can be elevated in malignancies other than pancreatic cancer (including cholangiocarcinomas) and many other benign pancreaticobiliary disorders including acute cholangitis, cirrhosis and other cholestatic diseases.

Adenocarcinoma found in the upper esophagus is an uncommon occurrence seldom encountered. While the esophageal carcinoma in the present case is likely an early manifestation of metastatic disease arising from an initially radiographically absent pancreatic primary, other etiologies must be considered. Another possible differential diagnosis with the rare but documented potential to result in the formation of an upper esophageal adenocarcinoma is a focus of gastric heterotopia. Ectopic gastric mucosa is typically an asymptomatic finding that is incidentally diagnosed during endoscopic biopsies, and has an estimated incidence ranging from 3.6%-10%[27,28]. If visualized endoscopically, gastric heterotopia is often a salmon colored round patch that is well demarcated from surrounding esophageal stratified squamous mucosa[29]. Histologically, gastric heterotopia has fundic type gastric mucosa with chief and parietal cells commonly in the absence of clinically evident reflux symptoms[28]. It is thought that ectopic gastric tissue stems from incomplete replacement of columnar epithelium with squamous epithelium during fetal development, or it is acquired later in life from chronic reflux, like the patho-physiologic development of Barrett’s esophagus[30-33].

Gastric heterotopia resulting in proximal esophageal adenocarcinoma is a rare occurrence, with less than 5 dozen cases reported. While the mechanism of invasive carcinoma arising from gastric heterotopia is unknown, it is possible that it occurs through a metaplasia-dysplasia cascade in a similar fashion invasive carcinoma arises from Barret’s esophagus[33]. In the setting of Barrett’s esophagus, intestinal metaplasia replaces the stratified squamous epithelial layer that normally lines the esophagus with mucin containing goblet cells scattered amongst a background of foveolar columnar epithelium[34]. In the rare occurrence of histologic progression to a neoplastic process, dysplasia of gastric mucosa or intestinal metaplasia may be present[29]. Interestingly, in adenocarcinomas attributed to proximal esophageal gastric heterotopia, intestinal metaplasia associated with BE is reported in approximately 5% of cases and only sporadically through case reports[35]. In the present case, esophageal biopsy demonstrated glandular epithelium, high grade columnar dysplasia with papillary architecture, and nuclear crowding and hyperchromasia with overlying squamous epithelium consistent with the esophageal mucosa. Histology consistent with gastric heterotropia was not found, making this possibility a less likely cause of the proximal esophageal carcinoma.

PAC is an aggressive malignancy that has often metastasized by the time symptoms manifest. Metastatic disease presenting as an earache has not been described before in the literature and is indicative of the profound and potentially early metastatic potential of PAC. Furthermore, dysphagia due to esophageal metastasis is a rarely described and often early phenomenon in the disease course consistent with advanced disease. Metastatic PAC without a detectable primary mass is a unique clinical scenario and patients with esophageal metastasis of unknown primary lesions should be monitored closely for the interval development of PAC. While not diagnostic in the nascence of a primary lesion, CA19-9 may be useful in discerning whether PAC is the primary disease in certain circumstances.

| 1. | Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2140-2141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13300] [Cited by in RCA: 15622] [Article Influence: 2231.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 3. | Yachida S, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. The pathology and genetics of metastatic pancreatic cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:413-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Friberg S, Nyström A. Cancer Metastases: Early Dissemination and Late Recurrences. Cancer Growth Metastasis. 2015;8:43-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McGuigan A, Kelly P, Turkington RC, Jones C, Coleman HG, McCain RS. Pancreatic cancer: A review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:4846-4861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1338] [Cited by in RCA: 1341] [Article Influence: 167.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (47)] |

| 6. | Makohon-Moore A, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Pancreatic cancer biology and genetics from an evolutionary perspective. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:553-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mohammed S, Van Buren G 2nd, Fisher WE. Pancreatic cancer: advances in treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:9354-9360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Caldas C, Kern SE. K-ras mutation and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Pancreatol. 1995;18:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Malkoski SP, Wang XJ. Two sides of the story? Smad4 loss in pancreatic cancer versus head-and-neck cancer. FEBS Lett. 2012;586:1984-1992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, Antal T, Leary R, Fu B, Kamiyama M, Hruban RH, Eshleman JR, Nowak MA, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Iacobuzio-Donahue CA. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2041] [Cited by in RCA: 1982] [Article Influence: 123.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rhim AD, Mirek ET, Aiello NM, Maitra A, Bailey JM, McAllister F, Reichert M, Beatty GL, Rustgi AK, Vonderheide RH, Leach SD, Stanger BZ. EMT and dissemination precede pancreatic tumor formation. Cell. 2012;148:349-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1400] [Cited by in RCA: 1711] [Article Influence: 122.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fidler IJ. Metastasis: quantitative analysis of distribution and fate of tumor emboli labeled with 125 I-5-iodo-2'-deoxyuridine. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970;45:773-782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Barreto SG, Shukla PJ, Shrikhande SV. Tumors of the Pancreatic Body and Tail. World J Oncol. 2010;1:52-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shoup M, Conlon KC, Klimstra D, Brennan MF. Is extended resection for adenocarcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas justified? J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:946-952; discussion 952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Christein JD, Kendrick ML, Iqbal CW, Nagorney DM, Farnell MB. Distal pancreatectomy for resectable adenocarcinoma of the body and tail of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:922-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rosati LM, Kummerlowe MN, Poling J, Hacker-Prietz A, Narang AK, Shin EJ, Le DT, Fishman EK, Hruban RH, Yang SC, Weiss MJ, Herman JM. A rare case of esophageal metastasis from pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: a case report and literature review. Oncotarget. 2017;8:100942-100950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Langton L, Laws JW. Dysphagia in carcinoma of the pancreas. J Fac Radiol. 1954;6:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bronstein YL, Loyer EM, Kaur H, Choi H, David C, DuBrow RA, Broemeling LD, Cleary KR, Charnsangavej C. Detection of small pancreatic tumors with multiphasic helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Legmann P, Vignaux O, Dousset B, Baraza AJ, Palazzo L, Dumontier I, Coste J, Louvel A, Roseau G, Couturier D, Bonnin A. Pancreatic tumors: comparison of dual-phase helical CT and endoscopic sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1315-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Ichikawa T, Haradome H, Hachiya J, Nitatori T, Ohtomo K, Kinoshita T, Araki T. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: preoperative assessment with helical CT versus dynamic MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;202:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Farma JM, Santillan AA, Melis M, Walters J, Belinc D, Chen DT, Eikman EA, Malafa M. PET/CT fusion scan enhances CT staging in patients with pancreatic neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2465-2471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Strobel K, Heinrich S, Bhure U, Soyka J, Veit-Haibach P, Pestalozzi BC, Clavien PA, Hany TF. Contrast-enhanced 18F-FDG PET/CT: 1-stop-shop imaging for assessing the resectability of pancreatic cancer. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1408-1413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gutzeit A, Antoch G, Kühl H, Egelhof T, Fischer M, Hauth E, Goehde S, Bockisch A, Debatin J, Freudenberg L. Unknown primary tumors: detection with dual-modality PET/CT--initial experience. Radiology. 2005;234:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Forsmark CE, Lambiase L, Vogel SB. Diagnosis of pancreatic cancer and prediction of unresectability using the tumor-associated antigen CA19-9. Pancreas. 1994;9:731-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ballehaninna UK, Chamberlain RS. The clinical utility of serum CA 19-9 in the diagnosis, prognosis and management of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: An evidence based appraisal. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:105-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 26. | Goonetilleke KS, Siriwardena AK. Systematic review of carbohydrate antigen (CA 19-9) as a biochemical marker in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:266-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 31.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Poyrazoglu OK, Bahcecioglu IH, Dagli AF, Ataseven H, Celebi S, Yalniz M. Heterotopic gastric mucosa (inlet patch): endoscopic prevalence, histopathological, demographical and clinical characteristics. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:287-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Borhan-Manesh F, Farnum JB. Incidence of heterotopic gastric mucosa in the upper oesophagus. Gut. 1991;32:968-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chong VH. Clinical significance of heterotopic gastric mucosal patch of the proximal esophagus. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:331-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tanaka M, Ushiku T, Ikemura M, Shibahara J, Seto Y, Fukayama M. Esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in cervical inlet patch with synchronous Barrett's esophagus-related dysplasia. Pathol Int. 2014;64:397-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | von Rahden BH, Stein HJ, Becker K, Liebermann-Meffert D, Siewert JR. Heterotopic gastric mucosa of the esophagus: literature-review and proposal of a clinicopathologic classification. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:543-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Chejfec G, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Is there a link between cervical inlet patch and Barrett's esophagus? Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:717-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Riddiough GE, Hornby ST, Asadi K, Aly A. Gastric adenocarinoma of the upper oesophagus: A literature review and case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;30:205-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jain S, Dhingra S. Pathology of esophageal cancer and Barrett's esophagus. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Peitz U, Vieth M, Evert M, Arand J, Roessner A, Malfertheiner P. The prevalence of gastric heterotopia of the proximal esophagus is underestimated, but preneoplasia is rare - correlation with Barrett's esophagus. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

P-Reviewer: Sugimura H, Vagholkar K S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL