Published online Dec 24, 2020. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v11.i12.1070

Peer-review started: July 16, 2020

First decision: August 7, 2020

Revised: August 20, 2020

Accepted: October 20, 2020

Article in press: October 20, 2020

Published online: December 24, 2020

Processing time: 149 Days and 1.3 Hours

Abdominoperineal excision (APE)-related hemorrhage can be challenging due to difficult access to pelvic organs and the risk of massive blood loss. The objective of the present study was to demonstrate the use of preoperative embolization (PE) as a strategy for blood preservation in a patient with a large low rectal tumor with a high risk of bleeding, scheduled for APE.

A 56-year-old man presented to our institution with a one-year history of anal bleeding and rectal tenesmus. The patient was diagnosed with bulky adenocarcinoma limited to the rectum. As the patient refused any clinical treatment, surgery without previous neoadjuvant chemoradiation was indicated. The patient underwent a tumor embolization procedure, two days before surgery performed via the right common femoral artery. The tumor was successfully devascularized and no major bleeding was noted during APE. Postoperative recovery was uneventful and a one-year follow-up showed no signs of recurrence.

Therapeutic tumor embolization may play a role in bloodless surgeries and increase surgical and oncologic prognoses. We describe a patient with a bulky low rectal tumor who successfully underwent preoperative embolization and bloodless abdominoperineal resection.

Core Tip: Abdominoperineal excision (APE) remains a major surgery with considerable morbidity. Half of patients undergoing APE have some type of postoperative complication, and bleeding requiring transfusion of blood products is the main morbidity of the procedure. Preoperative embolization as a strategy for blood preservation in a giant rectal hemangioma has been successfully described.

- Citation: Feitosa MR, de Freitas LF, Filho AB, Nakiri GS, Abud DG, Landell LM, Brunaldi MO, da Rocha JJR, Feres O, Parra RS. Preoperative rectal tumor embolization as an adjunctive tool for bloodless abdominoperineal excision: A case report. World J Clin Oncol 2020; 11(12): 1070-1075

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v11/i12/1070.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v11.i12.1070

An abdominoperineal excision (APE) consists on a combined abdominal and perineal resection of the anorectum and may be performed in benign conditions and malignancies. In low rectal cancer, advances in chemoradiotherapy and surgical devices have warranted a decrease in APE rates. Nevertheless, in those cases with anal sphincter involvement, the operation may undoubtedly be an alternative for oncologic control[1].

Despite the evolution of colorectal surgery, such as the development of laparoscopic access and robotic surgery, proctectomy remains a major surgery with considerable morbidity[2]. Approximately half of patients undergoing APE have some type of postoperative complication, and bleeding requiring transfusion of blood products is the main morbidity of the procedure[3].

APE-related hemorrhage can be challenging due to difficult access to pelvic organs and the risk of massive blood loss (> 1000 mL of blood)[4]. Furthermore, blood loss and blood transfusions have been associated with worse oncologic and postoperative outcomes in non-metastatic colorectal cancer. This effect is not completely understood but immunomodulatory signals leading to immunosuppression may be involved in adverse events[5].

The concept of bloodless surgery involves a series of perioperative strategies to prevent transfusion of blood products[6]. Recent studies have shown promising results in patients who have adopted this strategy, in bloodless centers[7]. Of note, the positive effect on surgical results depends on the adoption of adequate blood conservation methods[6]. The objective of the present study was to demonstrate the use of preoperative embolization (PE) as a strategy for blood preservation in a patient with a large low rectal tumor with a high risk of bleeding, scheduled for APE.

The patient was a 56-year-old man who suffered from anal bleeding and rectal tenesmus.

He presented to our institution with a one-year history of anal bleeding and rectal tenesmus. Worsening of symptoms was progressive. The patient also reported anorectal pain and weigh loss (15% of body weight in the same period).

No underlying diseases were reported by the patient.

Physical examination was normal, except for a rectal mass starting 1 cm from the anal border, circumferential and obstructive.

Laboratory tests were normal, except for a hemoglobin level of 9.4 g/dL. Carcinoembryonic antigen level was 3.34 ng/mL.

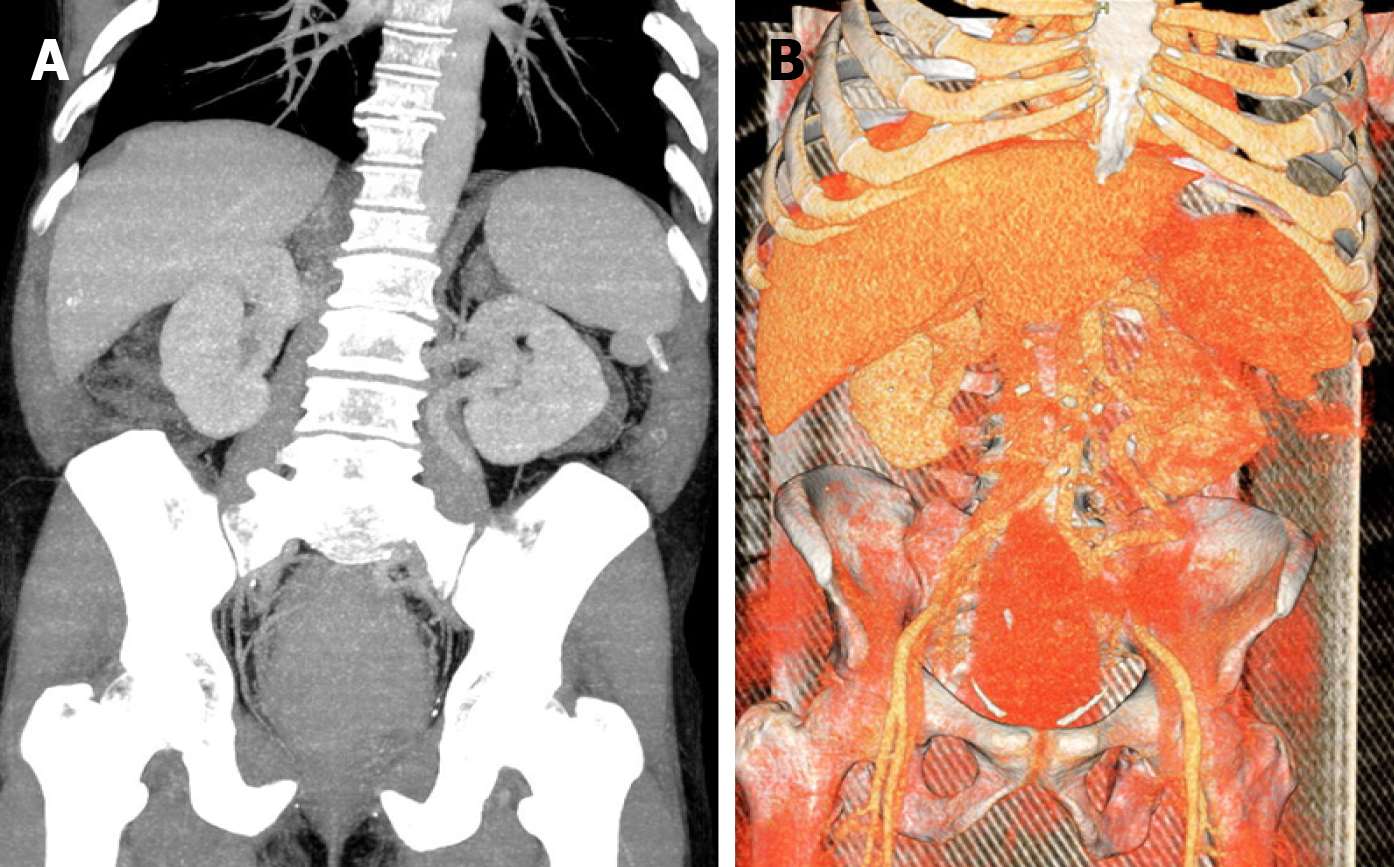

Colonoscopy was incomplete due to the bulky rectal mass. Tumor biopsy revealed a rectal adenocarcinoma. Abdominal and thoracic contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans showed extensive parietal thickening of the rectum, with an extension of 17.5 cm without signs of locoregional and distant metastasis (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with bulky adenocarcinoma limited to the rectum. As he refused any clinical treatment, surgery without previous neoadjuvant chemoradiation was indicated.

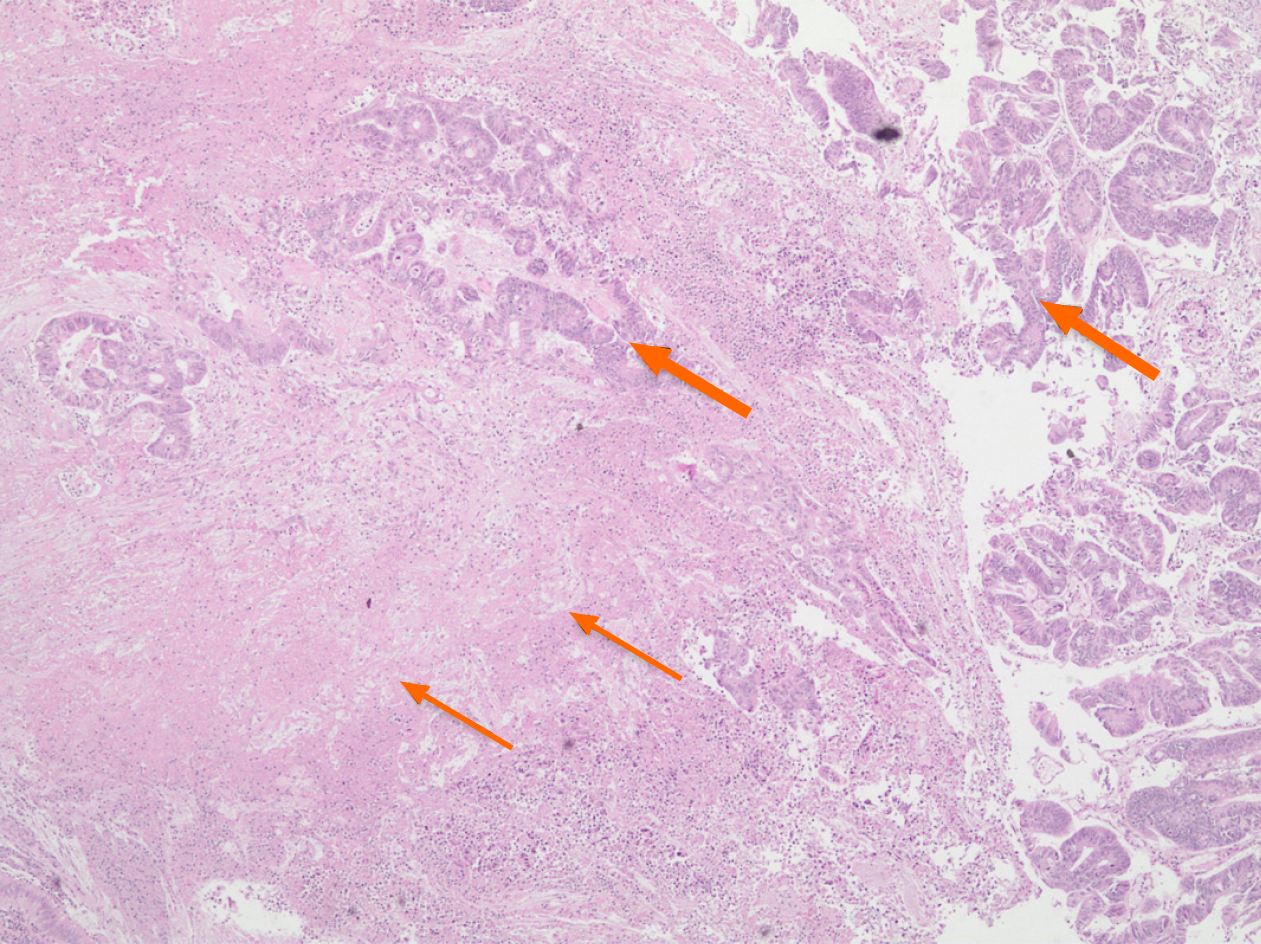

The patient also refused blood transfusion due to religious belief. To decrease bleeding during surgery, the patient underwent a tumor embolization procedure, two days before surgery performed via the right common femoral artery. Devascularization was performed with regular micra tris-acryl gelatin microspheres (500 μm) until partial reduction of vascular flow in the tumor topography. Metal coils were also released in the main trunk of the rectal arteries with subsequent administration of acrylic glue (25% n-butyl-cyanoacrylate). Angiographic control evidenced occlusion of the main branch and preservation of collateral circulation of the rectum and part of the tumor topography by small adjacent rectal branches (Figure 2). Regarding the surgical procedure, due to the absence of an adequate anal margin, we opted for an APE with total mesorectum excision and terminal colostomy in the upper left quadrant of the abdomen. A large rectal tumor occupying the entire pelvis was diagnosed, and there was no involvement of other abdominal organs (Figure 3). There was no blood transfusion during the operation. Pre- and postoperative hemoglobin levels were 9.4 and 9.1 g/dL, respectively. Analysis of the surgical specimen showed an adenocarcinoma of the rectum and anal canal, 15 cm in longitudinal length and invasion of the muscularis propria. A total of 54 disease-free lymph nodes were retrieved. There was no angiolymphatic and perineural invasion; however, extensive tumor necrosis was observed (Figure 4).

Surgical margins were free of neoplasia and tumor staging was classified as pT2pN0cM0. The patient was discharged on the 7th postoperative day due to a metabolic ileus clinically managed. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not performed and no synchronous colonic neoplasms were diagnosed during the colonoscopy performed three months after surgery. Clinical evaluation 12 mo after surgery, showed no evidence of cancer recurrence.

Under normal conditions, the evaluation of blood supply in the distal rectum and mesorectum shows a predominance of blood vessels within the rectal wall[8]. In rectal cancer patients contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound imaging usually reveals well vascularized masses with inhomogeneous enhancement of the contrast resulting from necrotic areas[9]. In the reported case, although atypical, a hypervascularized mass, with a predominance of blood vessels in the mesorectum was observed, as demonstrated by imaging exams. This hypervascularization is a hallmark of cancer and may be associated with the worst oncologic outcomes and with surgical complications (accidents during dissection and greater blood loss)[10].

The most common measures of blood conservation in oncologic patients have been discussed elsewhere and can be grouped according to the period in which they are started[6]. In APE patients, preoperative measures include treatment of anemia, suspension of substances that interfere with coagulation and careful procedure. Intraoperatively, it is important to minimize surgical trauma and to identify the proper surgical plane to perform a fine total mesorectal excision. Also, there is potential for autologous blood salvage and autologous normovolemic hemodilution. Postoperatively, lower levels of hemoglobin should be tolerated whenever possible and laboratory testing should be reduced to a minimum[6].

PE as a strategy to reduce intraoperative blood loss is a concept that has been developed for several anatomical territories. In pelvic tumors, devascularization rates greater than 75% can be obtained[11]. In our experience, PE was safe and successfully reduced intraoperative bleeding in a patient with a giant cavernous hemangioma of the rectum[12]. Although relatively simple and safe, PE can lead to significant tumor necrosis and a higher risk of bleeding, therefore, surgical resection of the tumor mass must be performed early. At our institution, we perform the definitive operation within 48 h after PE.

To the best of our knowledge, PE of bulky rectal tumors with modern techniques has not been described; however the rationale sounds reasonable, since a correlation between devascularization and less blood loss has been observed in other hypervascular tumors such as in renal masses[13]. In our experience, preoperative embolization of locally advanced rectal tumors reduces the blood content within bulky masses and can be used as an effective and safe adjunct to blood conservation. However, prospective and randomized studies are necessary to reveal the causal relationship between PE and reduced blood loss in bulky rectal masses.

Based on our experience and on a literature review we believe that preoperative embolization of rectal cancer may be an adjunctive tool in bloodless rectal surgeries.

| 1. | Hawkins AT, Albutt K, Wise PE, Alavi K, Sudan R, Kaiser AM, Bordeianou L; Continuing Education Committee of the SSAT. Abdominoperineal Resection for Rectal Cancer in the Twenty-First Century: Indications, Techniques, and Outcomes. J Gastrointest Surg. 2018;22:1477-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Han C, Yan P, Jing W, Li M, Du B, Si M, Yang J, Yang K, Cai H, Guo T. Clinical, pathological, and oncologic outcomes of robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic proctectomy for rectal cancer: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. Asian J Surg. 2020;43:880-890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tooley JE, Sceats LA, Bohl DD, Read B, Kin C. Frequency and timing of short-term complications following abdominoperineal resection. J Surg Res. 2018;231:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bonello VA, Bhangu A, Fitzgerald JE, Rasheed S, Tekkis P. Intraoperative bleeding and haemostasis during pelvic surgery for locally advanced or recurrent rectal cancer: a prospective evaluation. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18:887-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kwon HY, Kim BR, Kim YW. Association of preoperative anemia and perioperative allogenic red blood cell transfusion with oncologic outcomes in patients with nonmetastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol. 2019;26:e357-e366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Frank SM, Chaturvedi S, Goel R, Resar LMS. Approaches to Bloodless Surgery for Oncology Patients. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2019;33:857-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Resar LM, Wick EC, Almasri TN, Dackiw EA, Ness PM, Frank SM. Bloodless medicine: current strategies and emerging treatment paradigms. Transfusion. 2016;56:2637-2647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Murad-Regadas SM, Regadas FSP, Dealcanfreitas ID, Regadas Filho FSP, Fernandes GOdS, Albuquerque MCF, Regadas CM, Regadas MM. Establishing the normal ranges of female and male anal canal and rectal wall vascularity with color Doppler anorectal ultrasonography. J Col. 2018;38:207-213. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cartana ET, Gheonea DI, Cherciu IF, Streaţa I, Uscatu CD, Nicoli ER, Ioana M, Pirici D, Georgescu CV, Alexandru DO, Şurlin V, Gruionu G, Săftoiu A. Assessing tumor angiogenesis in colorectal cancer by quantitative contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound and molecular and immunohistochemical analysis. Endosc Ultrasound. 2018;7:175-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Seeber A, Gunsilius E, Gastl G, Pircher A. Anti-Angiogenics: Their Value in Colorectal Cancer Therapy. Oncol Res Treat. 2018;41:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shimohira M, Nagai K, Hashizume T, Nakagawa M, Ozawa Y, Sakurai K, Matsushita Y, Yamada S, Otsuka T, Shibamoto Y. Preoperative transarterial embolization using gelatin sponge for hypervascular bone and soft tissue tumors in the pelvis or extremities. Acta Radiol. 2016;57:457-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carvalho RGd, Feitosa MR, Urbano G, Guzela VR, Joviliano EE, Féres O, Rocha JJRD. Preoperative embolization of a cavernous hemangioma of the rectum. J Col. 2014;34:52-54. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li D, Pua BB, Madoff DC. Role of embolization in the treatment of renal masses. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2014;31:70-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Yoon YS S-Editor: Fan JR L-Editor: Webster JR P-Editor: Wang LL