Published online Dec 24, 2019. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v10.i12.382

Peer-review started: June 4, 2019

First decision: August 2, 2019

Revised: September 9, 2019

Accepted: November 4, 2019

Article in press: November 4, 2019

Published online: December 24, 2019

Processing time: 202 Days and 10.8 Hours

Weight gain is a potential negative outcome of breast-cancer treatment, occurring in 50%-to-96% of breast-cancer patients, although the amount of weight gain is inconsistently reported in the literature. Research has also shown a relationship between overweight/obesity and breast-cancer mortality. Correspondingly, weight management is a self-care approach known to benefit quality of life (QOL). These research questions and analysis add to existing literature by examining participants’ body mass index (BMI) trend and its relationship with QOL indicators over seven years.

To examine: (1) BMI trends among breast cancer survivors; and (2) The trends’ relationship to QOL indicators over seven years.

During the Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Project, 378 patients’ weight and height were recorded by nurses prior to or just after beginning breast cancer treatment and repeated at quarterly-to-semiannual intervals over seven years. Additionally, participants annually completed the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), a valid and reliable tool assessing QOL and health concepts, including physical function, pain, and emotional well-being. BMI trends, change in BMI, and change in SF-36 subscales over seven years were calculated using a random-intercept repeated-measures regression. Patients were placed into BMI categories at each time point: Normal, Overweight and Obese. As patients’ weights changed, they were categorized accordingly.

During the seven-year study and while controlling for age and residence, participants gained an average of 0.3534 kg/m2 (P = 0.0009). This amount remained fairly consistent across BMI categories with those in the normal-weight category (n = 134) gaining 0.4546 kg/m2 (P = 0.0003); Overweight (n = 190) gaining 0.2985 kg/m2 (P = 0.0123); and obese (n = 199) gaining 0.3147 kg/m2, (P = 0.0649). Age (under or over 55) and region (metro/micro vs small/rural) were significantly associated with BMI increase in both the normal and obese categories. There were statistically significant (P < 0.0100) changes in five of the eight SF-36 domains; however, the directions of change were different and somewhat divergent from that hypothesized. Controlling for age and region, these five were statistically significant, so there were no change or differences between the micropolitan/metropolitan and small town/rural groups.

Although only modest increases in mean BMI were observed, mean BMI change was associated with selected QOL indicators, suggesting the continued need for self-care emphasis during breast cancer survivorship.

Core tip: This analysis examined body mass index (BMI) and quality of life (QOL) data from over 300 breast cancer patients from diagnosis to seven years’ survival. BMI trends and quality of life adjustments were recognized. The need for continued support and surveillance through the years of survivorship is underscored. The results support continued research in this important area. Application of such findings for survivorship care-planning in the clinical setting has potential to enhance optimal self-care and QOL in living with a chronic condition such as breast cancer survivorship.

- Citation: Anbari AB, Deroche CB, Armer JM. Body mass index trends and quality of life from breast cancer diagnosis through seven years’ survivorship. World J Clin Oncol 2019; 10(12): 382-390

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v10/i12/382.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v10.i12.382

There are 3.5 million breast cancer survivors (BCS) living in the United States[1]. Increasingly, women diagnosed with breast cancer are living longer and healthier lives. However, they are at a lifelong risk for developing complications from their previous cancer treatments[2]. Knowing this, emphasis has been placed on survivorship care-planning which highlights the specific needs of BCS, including mitigating the psychological and physical effects of treatment, as well as promoting healthy behaviors[2].

Weight gain is a potential negative outcome of breast cancer treatment, occurring in 50% to 96% of breast cancer patients[3]. More recently, Raghavendra et al[4] found that 33.7% of 1281 long-term survivors in their study gained more than 5% of their pre-treatment weight after 5 years of endocrine therapy. That said, the amount of weight gain and reasons for it remain inconsistently reported in the literature[5-9]. Research has also shown a relationship between overweight/obesity and breast-cancer mortality[3,8,10].

Both weight loss and gain remain common after treatment for breast cancer, with weight loss being a marker for mortality risk[5]. Moreover, weight gain after breast cancer diagnosis (treatment) has been associated with higher risk for co-morbid conditions such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease[11]. However, weight gain or a higher body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis have also been found to actually increase certain quality of life (QOL) domains[12]. Regardless of amount or timing, weight gain and body changes caused by cancer treatments are known to cause distress among BCS[9,13].

The impact of a breast cancer diagnosis and treatment sequelae on QOL domains can vary depending on the age and rural/urban residence of the survivor. The median age of a BCS is 62 years which means they typically have many additional years of specific survivorship care ahead of them, activities involving special screening and/or symptom management[1]. In addition, BCS living in rural areas may face different challenges than their urban counterparts. First, women living in rural settings are more likely to have higher BMI at diagnosis of breast cancer[14]. Furthermore, rural BCS may face additional difficulties in accessing follow-up care, adjusting to new roles or limitations, and navigating mental health changes[15].

This study’s purpose was to examine: (1) BMI trends among BCS; and (2) The trends’ relationship to QOL indicators over seven years’ survivorship as measured by the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36). Research questions were: (1) How do patients’ BMI change from breast cancer diagnosis to seven years’ survivorship? and (2) When controlling for age and rural residence, what is the relationship between BMI change and QOL (as indicated by change in SF-36 subscale scores) from diagnosis to seven years’ survivorship?

During the Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Project, 378 women diagnosed with breast cancer agreed to have their weight and height recorded by nurses prior to or just after beginning breast cancer treatment as a part of their overall survivorship assessment[16]. An initial height was measured in centimeters by the research nurses using a wall-mounted height rod. Weight measurements using a standing scale were repeated at quarterly-to-semiannual intervals over the following seven years (17 total possible visits; Visit 1 through Visit 17). For analysis purposes, Time 1 was either right after diagnosis or right after the first treatment (surgery). Time points from that point forward corresponded to quarterly, semi-annually, and annual measurements during study enrollment. The study was approved by the Health Sciences Institutional Review Board and all participants signed an informed consent.

BMI was calculated using the participant’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of her height in meters (kg/m2). BMI was calculated and recorded for each study visit. For this analysis, participants were assigned into one of three BMI categories of Normal (BMI equal to 18.5000 to 24.9999), Overweight (BMI equal to 25.0000 to 29.9999), and Obese (BMI greater than or equal to 30.0000). The six participants with BMIs in the Underweight category (BMI less than 18.5000) were included in the Normal category for analysis.

Participants’ dates of birth were collected upon enrollment in the study and used to calculate age by comparison to date of each data collection time point. Participants’ zip codes were collected upon enrollment in the study at the time of diagnosis. Participants were placed into two categories using the Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes (RUCA) for zip code categorization process provided by United States Department of Agriculture[17]. For this analysis we chose to compare Micropolitan/Metropolitan and Small Town/Rural.

Finally, participants completed the SF-36 annually. Participants were given the survey to fill out on their own and return to the research office. The SF-36 is a valid and reliable tool assessing QOL and health domains, including physical function, pain, and emotional well-being[18]. The SF-36 is publicly available and has been frequently used to assess breast cancer and QOL[19,20]. It includes eight health concepts or subscales: (1) Limitations in physical activities; (2) Limitations in social activities; (3) Limitations in usual role activities; (4) Pain; (5) Mental health; (6) Limitations in role activities related to emotional well-being; (7) Vitality; and (8) General health perceptions[15]. The SF-36 survey has consistent reliability; 0.93 (physical functioning) and 0.90 (mental health); to 0.82 to 0.85 (bodily pain, emotional and physical attribution, and social functioning); to 0.78 (general health perceptions)[21].

BMI trends: Patients were placed into one of the three BMI categories at each time point: Normal, Overweight, and Obese. As a patient’s weight changed, she was recategorized accordingly. Using a random-intercept repeated-measures regression analysis, BMI trends within each of the BMI categories were assessed using a sample size equal to 322 and 4059 observations. This method was used because the data were rich and longitudinal and allowed accounting for the non-dependency between observations within a participant[22]. Results of this method modeled the average BMI change over time, while also controlling for other influences on BMI change, such as region and age. The random-intercept model allows each person to have her own starting point (intercept) while the slopes are assumed equal.

Using the 2010 RUCA codes, participants were grouped into two regional categories: micropolitan/metropolitan (more than 50000 persons); and rural/small town (less than 49999)[17]. Using just above the median age of the natural onset of menopause[23], which can influence weight changes, participants were grouped into two categories: Under 55 years of age and equal to or over 55 years of age.

Change in BMI and SF-36 subscale scores: Change in BMI and its relationship to the SF-36 scores in each of the eight QOL domains was calculated using a repeated-measures general linear mixed model with a variance components covariance structure. The variance components covariance structure assumes equal correlation between any two time-points, in this case, visits[22]. BMI change was the dependent variable and the change in the eight SF-36 domains were the independent variables, while controlling for age categorized into two groups (under 55 and equal to or over 55 years) and region categorized into two groups (micropolitan/metropolitan and rural/small).

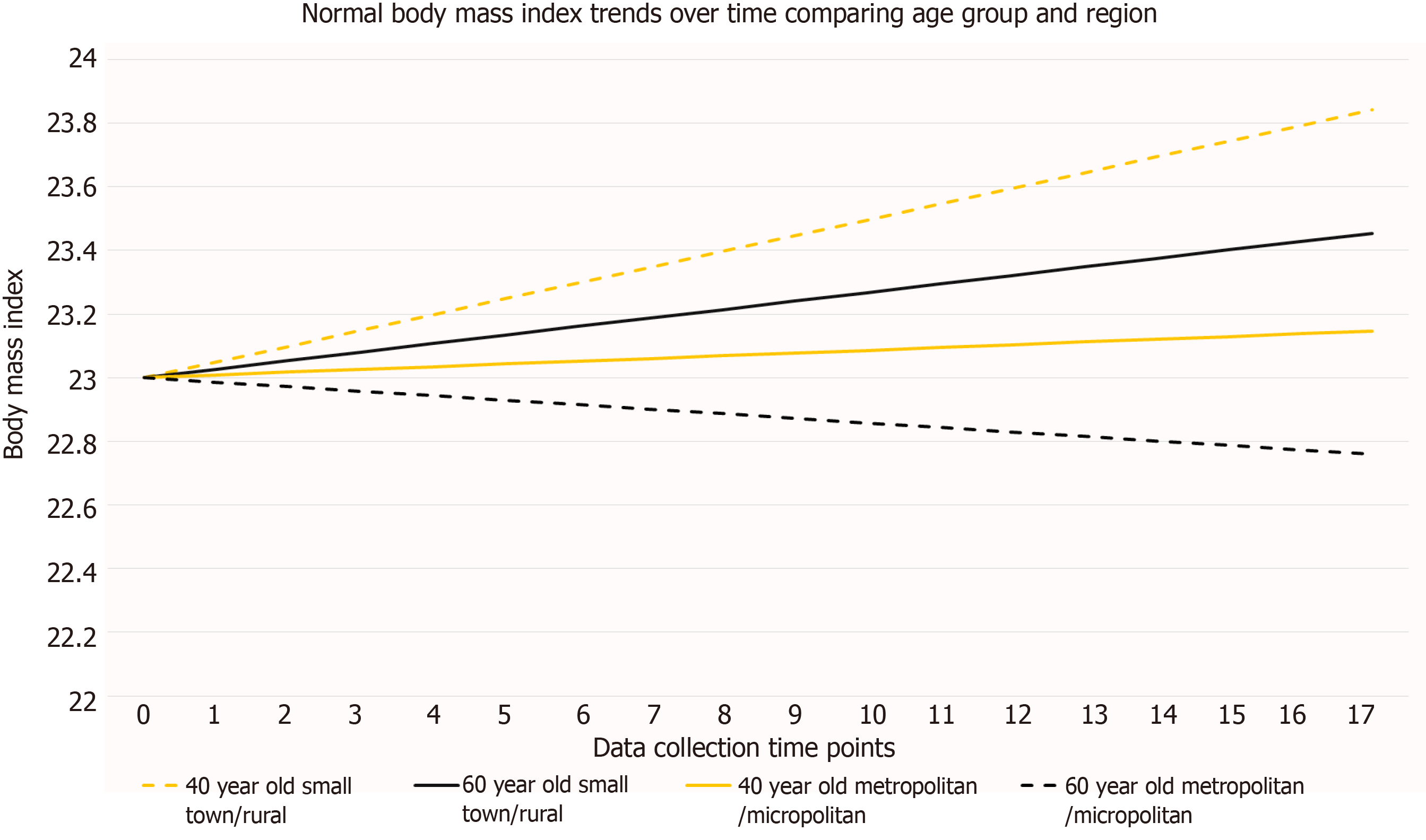

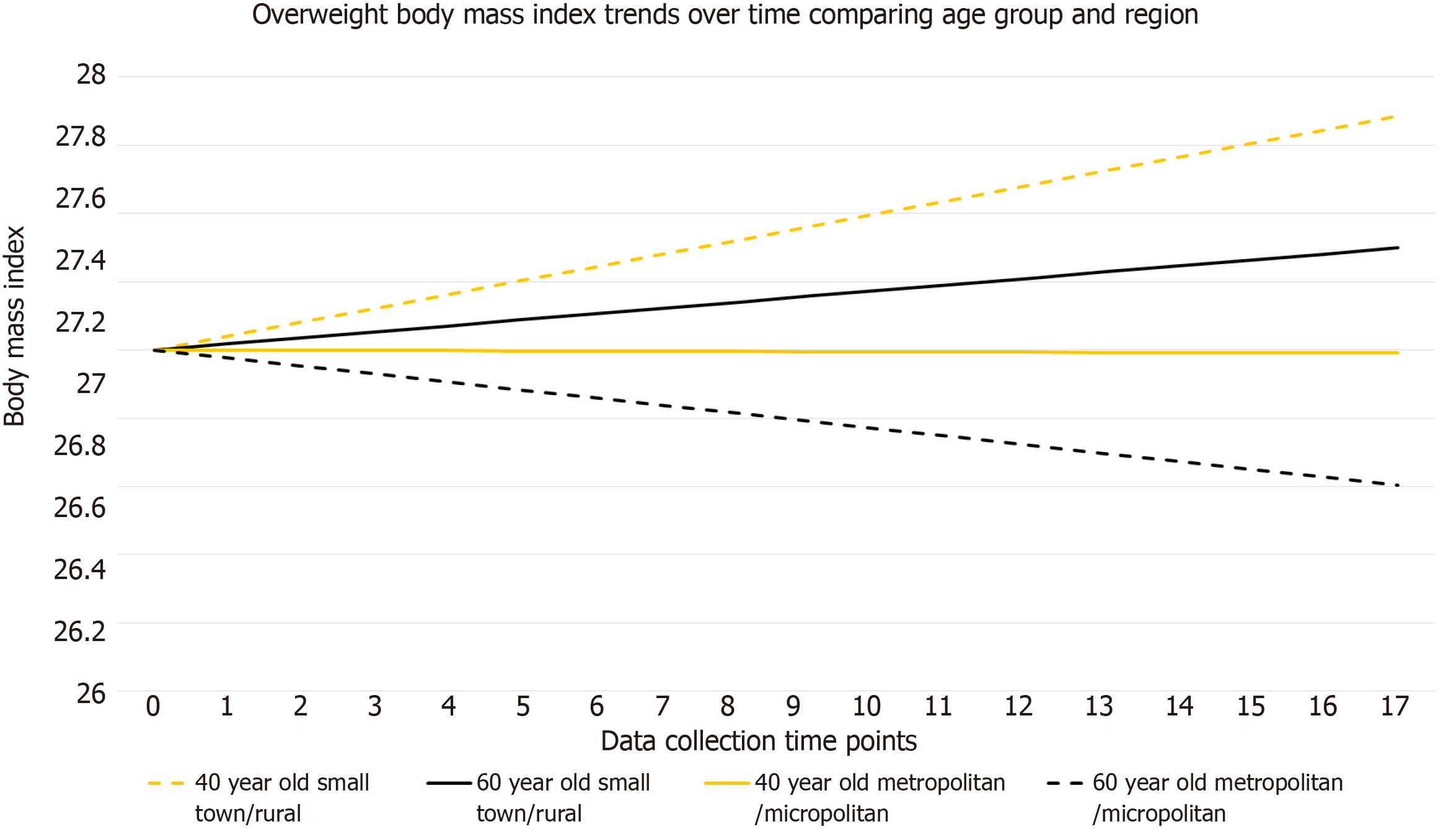

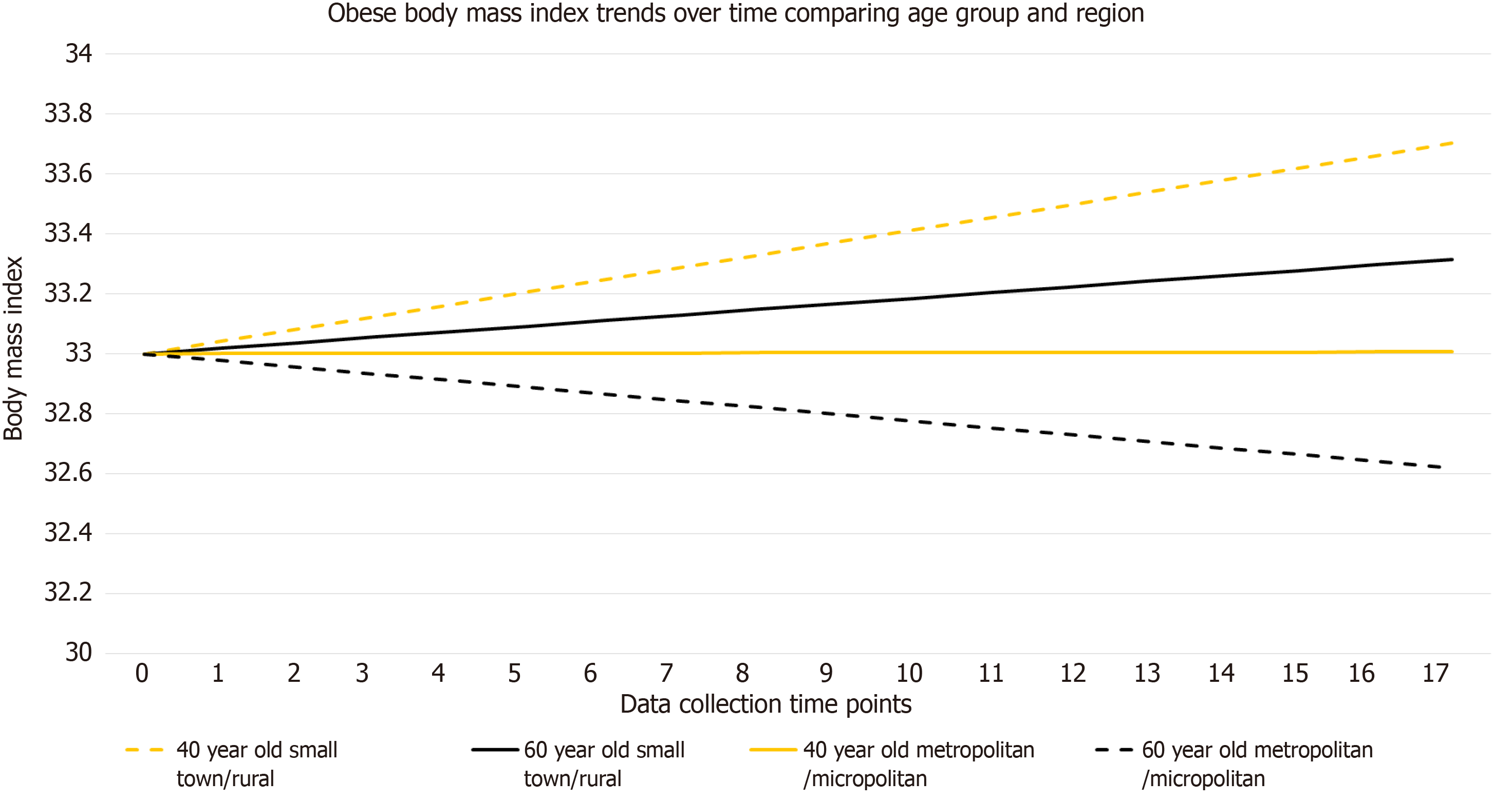

During the seven-year study (visit 1 to visit 17), participants gained an average of 0.3534 kg/m2 (P = 0.0009). This modest gain remained fairly consistent across BMI categories, with those in the Normal category (n = 134) gaining 0.4546kg/m2 (P = 0.0003); Overweight (n = 190) gaining 0.2985 kg/m2 (P = 0.0123); and Obese (n = 199) gaining 0.3147 kg/m2, (P = 0.0649) as seen in Table 1 and Figures 1-3. For the normal BMI group, visit (time variable) was significant which indicates that on average, the normal group’s BMI changed significantly by 17 × 0.0267 or 0.4546 kg/m2 from visit 1 to visit 17 (P = 0.0003). Likewise, for the overweight BMI group, visit (time variable) was significant which indicates that on average, the group’s BMI changed significantly by 17 × 0.01756 or 0.2985 kg/m2 from visit 1 to visit 17 (P = 0.0123). Results were consistent for the obese group, with an estimated BMI increase of 0.0185 × 17 or 0.3146 kg/m2; however, this change did not meet the level of statistical significance (P = 0.0649). Age (under or over 55) and region (micro/metro vs rural/small) were significantly associated with BMI increase in both the normal and obese categories (P < 0.0500 for both categories).

| Normal group | Overweight group | Obese group | |

| Mean BMI change (SE) | Mean BMI change (SE) | Mean BMI change (SE) | |

| n = 134; 1007 observations | n = 190; 1311 observations | n = 195; 1741 observations | |

| Age (< 55 yr vs ≥ 55 yr) | -0.5349 kg/m2a (0.1141) | -0.01760 kg/m2 (0.2591) | 1.1078 kg/m2a (0.0815) |

| micropolitan/metropolitan vs small/rural | -0.6950 kg/m2a (0.1228) | 0.07948 kg/m2 (0.2549) | -0.7554 kg/m2a (0.0864) |

BMI change corresponded significantly (P < 0.0500) to five SF-36 domain scores: Physical functioning; role limitations related to physical functioning; role limitations related to emotional problems; social functioning; and energy/fatigue (Table 2). The relationships with these five domains were statistically significant when controlling for age and commuting region; however, there were no change or differences between the micropolitan/metropolitan and small town/rural groups. Referring to Table 2 and extrapolating this further, each domain is scaled to range zero to 100. If a person’s score changes from a 0 to 100 score, which would be extreme, but not necessarily impossible, within our sample, their BMI is expected to decrease by 0.5120 kg/m2. Considering the overweight BMI category is only 4.9000 kg/m2 wide (25.0000-29.9 kg/m2), this could be a clinically significant change.

| Effect | Estimate | SE | P value |

| 36-Item Short Form domain | |||

| Physical functioning | -0.0093 | 0.0033 | 0.0052 |

| Role limitations related to physical functioning | 0.0039 | 0.0016 | 0.0124 |

| Pain | 0.0023 | 0.0025 | 0.3643 |

| General health | -0.0004 | 0.0042 | 0.9181 |

| Emotional well-being | 0.0089 | 0.0048 | 0.0656 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | -0.0039 | 0.0017 | 0.0216 |

| Social functioning | 0.0079 | 0.0032 | 0.0135 |

| Energy fatigue | -0.0104 | 0.0037 | 0.0045 |

| Under 55 yr of age vs 55 and over | 0.3870 | 0.1156 | 0.0021 |

| micropolitan/metropolitan vs small town/rural | 0.0571 | 0.1149 | 0.6194 |

There were statistically significant changes in five of the eight SF-36 domains; however, their directions of change were varied and somewhat divergent from what one might hypothesize, as one might presume that QOL in each domain would decrease somewhat with weight gain. Although modestly, three QOL domains moved statistically significantly in the opposite direction as BMI – that is, as BMI increased, the participants’ QOL decreased, as would be hypothesized. These domains were: Physical functioning (SE = -0.0093; P = 0.0052); role limitations related to emotional problems (SE = -0.0039; P = 0.0216); and energy/fatigue (SE = -0.0104; P = 0.0045).

The remaining two statistically-significant QOL-affected domains, role limitations related to physical functioning (SE = 0.0039; P = 0.0052); and social functioning (SE = 0.0079; P = 0.0014), moved in the same direction as BMI, as would not necessarily be hypothesized to occur. For example, as social functioning increased, BMI is expected to also increase by 0.0082 kg/m2.

This analysis adds to the literature regarding weight changes during breast cancer treatment. Like previous findings, slight BMI changes were observed over the seven years post-diagnosis. The slight change was not surprising, as weight change over time of BCS has been found to be similar to non-BCS[24]. This finding could be supported by a number of possible reasons. Few studies control for location of residence (commuting region). Because residence was statistically significant and associated with weight gain, future research about residence and risk for weight gain for women diagnosed with breast cancer could reveal additional approaches to addressing this groups’ survivorship needs. There is also the possibility that, despite an intervention not being implemented during this prospective study, participants might have adjusted their health behaviors simply because they were being monitored over time. Thus, only slight BMI changes over seven years were realized.

BMI change was also modestly associated with selected QOL indicators, even when controlling for age and commuting region. Our results support previous studies that have found slightly overweight women might maintain a better QOL or observe less QOL changes, than their normal, obese, or even non-cancer counterparts[11]. Our results also support previous studies that found only slight weight gains over time with no association with age[4]. There is also the possibility that participants adjusted to their health status changes over the seven years of participation and thus only small changes in their QOL were reported. Similar findings were presented in a study by Tessier, Blanchin, and Sebille where an adaptation and shift in BCS’ subjective well-being and health-related QOL were noted over time[25].

This analysis did not control for or factor in the varying treatment regimens of participants. Different types and stages of breast cancer are approached differently and thus the long-term effects of treatment vary widely. Including types of treatments as a variable, with this already-limited sample size of 379 participants, would have weakened the power of the modeling used. A final consideration with this analysis is the age of the data collection time period of 2001 to 2008. Oncological surgical practices (e.g., breast conservation surgery and sentinel lymph node biopsy), neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy treatments, as well as duration, amount, and localization of radiation sessions, have evolved since completion of the data collection.

The modest increases in BMI, paired with modest changes in QOL, suggest the continued need for self-care emphasis during breast cancer survivorship. Self-care optimally includes weight management at a current state during treatment and survivorship, rather than an emphasis on weight loss. Young et al[26] found that BCS who gained weight or lost weight had a higher risk of functional limitations. Furthermore, exercise can improve physical function and body composition without overt weight loss, thus supporting encouragement of increasing physical activity and weight maintenance (rather than weight loss alone)[10]. These results support this finding that perhaps an emphasis on weight maintenance during and after treatment is a key component of survivorship care-planning. Rather than emphasis on weight loss, perhaps the approach and future research should surround weight maintenance (or prevention of weight gain) that involves increased physical activity and dietary adjustments, both known to reduce fatigue, increase cardiovascular health, and perhaps decrease body fat percentages[27]. Our findings support the notion that survivorship care-planning should involve the patient and should factor in age, commuting region, late side-effects, and health promotion[2,28].

Weight gain is a potential negative outcome of breast-cancer treatment, occurring in 50%-to-96% of breast cancer patients, although the amount of weight gain is inconsistently reported in the literature. Weight gain can influence quality of life (QOL) during survivorship and even cancer reoccurrence.

We were motivated to do this analysis to examine body mass index (BMI) trends among breast cancer survivors and the trends’ relationship to QOL indicators over seven years. Identifying trends and their relationships to QOL provides insight into cancer survivorship care and care-planning.

We conducted this analysis to assess BMI trends among breast cancer survivors and to investigate whether those trends were related to quality of life. We identified small positive upticks in BMI over time amongst our participants. Future research should continue to examine weight changes in this population.

Data for this analysis were collected during a study entitled the Breast Cancer and Lymphedema Project. Three-hundred seventy-eight women enrolled in the study at breast cancer diagnosis or just after surgery for breast cancer treatment. Participants were followed over seven years and the research team recorded their weight and 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) scores at designated intervals during the study. BMI trends, change in BMI, and change in SF-36 subscales over seven years were calculated using a random-intercept repeated-measures regression. This method was selected because the data were longitudinal, and it allows for non-dependency between collection time points.

We found small upward trends in our participants’ BMI and those upward trends corresponded in a statistically significant way to several of the SF-36 subscales. Age and region were also significantly associated with BMI increase in the normal and obese BMI categories. Our results add to the existing body of work regarding BMI and breast cancer treatment. These results contribute to what is known and support efforts to continue research into breast cancer survivorship and the potentially chronic sequelae of treatment.

We place an emphasis on the need for continued support and surveillance through the years of survivorship. Our results support continued research in breast cancer survivorship research. Application of weight management and health promotion for survivorship care-planning in the clinical setting has potential to enhance optimal self-care and QOL in living with a chronic condition such as breast cancer survivorship.

We believe future research involving breast cancer survivors should go beyond weight loss and perhaps focus more on weight management, healthy lifestyle changes, and health promotion. Our results also bring awareness to the potential influences of rural and urban environments and how those environments may contribute to our understanding of the issues surrounding cancer survivorship.

The research team would like to thank the research nurses and graduate student research assistants who assisted with the collection and management of these data and the cancer center clinical team who supported this research. We would especially like to thank the breast cancer survivors who volunteered to participate to help future survivors.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zhang YY S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Qi LL

| 1. | American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Facts & Figures 2017-2018. Atlanta: American Cancer Society 2017; 44 Available from: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistcs/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures/breast-cancer-facts-and-figures-2017-2018.pdf. |

| 2. | Runowicz CD, Leach CR, Henry NL, Henry KS, Mackey HT, Cowens-Alvarado RL, Cannady RS, Pratt-Chapman ML, Edge SB, Jacobs LA, Hurria A, Marks LB, LaMonte SJ, Warner E, Lyman GH, Ganz PA. American Cancer Society/American Society of Clinical Oncology Breast Cancer Survivorship Care Guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:43-73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 548] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 51.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vance V, Mourtzakis M, McCargar L, Hanning R. Weight gain in breast cancer survivors: prevalence, pattern and health consequences. Obes Rev. 2011;12:282-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Raghavendra A, Sinha AK, Valle-Goffin J, Shen Y, Tripathy D, Barcenas CH. Determinants of Weight Gain During Adjuvant Endocrine Therapy and Association of Such Weight Gain With Recurrence in Long-term Breast Cancer Survivors. Clin Breast Cancer. 2018;18:e7-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cespedes Feliciano EM, Kroenke CH, Bradshaw PT, Chen WY, Prado CM, Weltzien EK, Castillo AL, Caan BJ. Postdiagnosis Weight Change and Survival Following a Diagnosis of Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:44-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gross AL, May BJ, Axilbund JE, Armstrong DK, Roden RB, Visvanathan K. Weight change in breast cancer survivors compared to cancer-free women: a prospective study in women at familial risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24:1262-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Playdon MC, Bracken MB, Sanft TB, Ligibel JA, Harrigan M, Irwin ML. Weight Gain After Breast Cancer Diagnosis and All-Cause Mortality: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sadim M, Xu Y, Selig K, Paulus J, Uthe R, Agarwl S, Dubin I, Oikonomopoulou P, Zaichenko L, McCandlish SA, Van Horn L, Mantzoros C, Ankerst DP, Kaklamani VG. A prospective evaluation of clinical and genetic predictors of weight changes in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123:2413-2421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vance V, Mourtzakis M, Hanning R. Relationships Between Weight Change and Physical and Psychological Distress in Early-Stage Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42:E43-E50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Makari-Judson G, Braun B, Jerry DJ, Mertens WC. Weight gain following breast cancer diagnosis: Implication and proposed mechanisms. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:272-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 11. | Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1925-1932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1626] [Cited by in RCA: 1579] [Article Influence: 92.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xia J, Tang Z, Deng Q, Wang J, Yu J. Being slightly overweight is associated with a better quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pila E, Sabiston CM, Taylor VH, Arbour-Nicitopoulos K. "The Weight Is Even Worse Than the Cancer": Exploring Weight Preoccupation in Women Treated for Breast Cancer. Qual Health Res. 2018;28:1354-1365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Befort CA, Nazir N, Perri MG. Prevalence of obesity among adults from rural and urban areas of the United States: findings from NHANES (2005-2008). J Rural Health. 2012;28:392-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bettencourt BA, Schlegel RJ, Talley AE, Molix LA. The breast cancer experience of rural women: a literature review. Psychooncology. 2007;16:875-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Armer JM, Stewart BR. Post-breast cancer lymphedema: incidence increases from 12 to 30 to 60 months. Lymphology. 2010;43:118-127. [PubMed] |

| 17. | United States Department of Agriculture. United States Department of Agriculture 2010 Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes. 2016; Available from: https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-codes/documentation/. |

| 18. | Rand Health. 36-Item Short Form Survey from the RAND Medical Outcomes Study. Available from: https://www.rand.org/health/surveys_tools/mos/36-item-short-form.html. |

| 19. | Treanor C, Donnelly M. A methodological review of the Short Form Health Survey 36 (SF-36) and its derivatives among breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:339-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23352] [Cited by in RCA: 24482] [Article Influence: 720.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 21. | McHorney CA, Ware JE, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Med Care. 1993;31:247-263. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Diggle PJ, Heagarty P, Liang KY, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press 2002; 170-180. |

| 23. | Gold EB. The timing of the age at which natural menopause occurs. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2011;38:425-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yerushalmi R, Dong B, Chapman JW, Goss PE, Pollak MN, Burnell MJ, Levine MN, Bramwell VHC, Pritchard KI, Whelan TJ, Ingle JN, Shepherd LE, Parulekar WR, Han L, Ding K, Gelmon KA. Impact of baseline BMI and weight change in CCTG adjuvant breast cancer trials. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1560-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tessier P, Blanchin M, Sébille V. Does the relationship between health-related quality of life and subjective well-being change over time? An exploratory study among breast cancer patients. Soc Sci Med. 2017;174:96-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Young A, Weltzien E, Kwan M, Castillo A, Caan B, Kroenke CH. Pre- to post-diagnosis weight change and associations with physical functional limitations in breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8:539-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fazzino TL, Fabian C, Befort CA. Change in Physical Activity During a Weight Management Intervention for Breast Cancer Survivors: Association with Weight Outcomes. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25 Suppl 2:S109-S115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Alfano CM, Leach CR, Smith TG, Miller KD, Alcaraz KI, Cannady RS, Wender RC, Brawley OW. Equitably improving outcomes for cancer survivors and supporting caregivers: A blueprint for care delivery, research, education, and policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:35-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |