Published online Mar 5, 2026. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112754

Revised: September 11, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: March 5, 2026

Processing time: 190 Days and 12.2 Hours

Post-operative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is a common but often overlooked issue, especially in older adults after surgery. This review looks into how the gut and brain are connected—a relationship known as the gut-brain axis—and how tiny microbes living in our gut might influence our brain health during recovery. The gut microbiota helps produce important substances like short-chain fatty acids and neurotransmitters that play a key role in memory, mood, and brain fun

Core Tip: This review explores the important connection between gut health and brain function, especially in patients recovering from surgery. It focuses on how disturbances in gut microbes after surgery can lead to inflammation, impaired gut barrier function, and memory issues—collectively known as post-operative cognitive dysfunction. The article highlights growing evidence that restoring gut balance using probiotics and other microbiota-based therapies may help reduce inflammation and support better cognitive recovery. By drawing attention to the gut-brain link, this review opens up new possibilities for non-invasive strategies to protect the brain and improve mental clarity in post-surgical patients.

- Citation: Joshi R, Gupta N, Gupta A, Khanna P, Verma N, Kaur S. Gut-brain axis and post-operative cognitive dysfunction: A multifactorial perspective on microbiota, inflammation, and cognitive health. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2026; 17(1): 112754

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v17/i1/112754.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112754

The gut-brain axis (GBA) is an intricate and bidirectional communication network linking the gastrointestinal tract and the brain through neural, hormonal, and immune pathways. This axis plays a pivotal role in maintaining cognitive and emotional health. The concept of the GBA has garnered significant attention in recent years due to its growing recognition as a key factor in influencing brain function and overall mental well-being[1,2].

The gut microbiota, composed of trillions of microorganisms residing in the gastrointestinal tract, is crucial for various bodily functions, including digestion and immunity. However, its role extends beyond these traditional functions. Emerging research has demonstrated that the gut microbiota is integral in modulating cognition, mood, and neuroplasticity. These microorganisms produce a range of metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), neurotransmitters like serotonin, and neurotrophic factors such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)[3].

SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate, and acetate, are particularly significant as they influence brain function by modulating inflammation, energy homeostasis, and the integrity of the blood-brain barrier[4]. Certain gut microbes support brain function by promoting neurotransmitter synthesis and barrier integrity[2].

The gut microbiome refers to the diverse community of microorganisms—including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and archaea—residing primarily in the gastrointestinal tract[1,5]. These microbes collectively influence digestion, immunity, and neurological health through a network of neural, immune, and endocrine pathways known as the GBA[4,6]. Characterization of the gut microbiome is commonly performed using 16S rRNA sequencing for taxonomic profiling and shotgun metagenomic sequencing to assess microbial diversity, functional genes, and metabolic pathways[7,8]. Un

The primary aim of this review is to explore the potential of gut microbiota in promoting brain health and its therapeutic promise for addressing cognitive dysfunction through the GBA. We aim to shed light on its capacity to enhance cognitive resilience. The search strategy for the qualitative synthesis began with the identification of relevant studies through comprehensive database searches and other sources. The search strategy which we used were - ("Gut-Brain Axis" OR "Gut Microbiota" OR "Gut Metabolites") AND ("Cognitive Health" OR "Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction" OR "POCD") AND ("Microbial Modulation" OR "Intestinal Dysbiosis"), ("Gut-Brain Axis" AND "Gut Microbiota" AND "Cognitive Dysfunction") AND ("Postoperative Outcomes" OR "Surgical Cognitive Complications"), ("Gut Microbiota" AND ("Cognitive Health" OR "Cognitive Function") AND ("Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction" OR "Anesthesia")) AND ("Microbial Composition" OR "Gut Bacteria"), ("Gut Microbiota" AND "Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction" AND ("Metabolites" OR "Microbial Dysbiosis")) AND ("Inflammation" OR "Intestinal Permeability"), ("Gut-Brain Axis" AND "Post-Operative Cognitive Dysfunction") AND ("Neuroinflammation" OR "Microbiota-Immune Interaction").

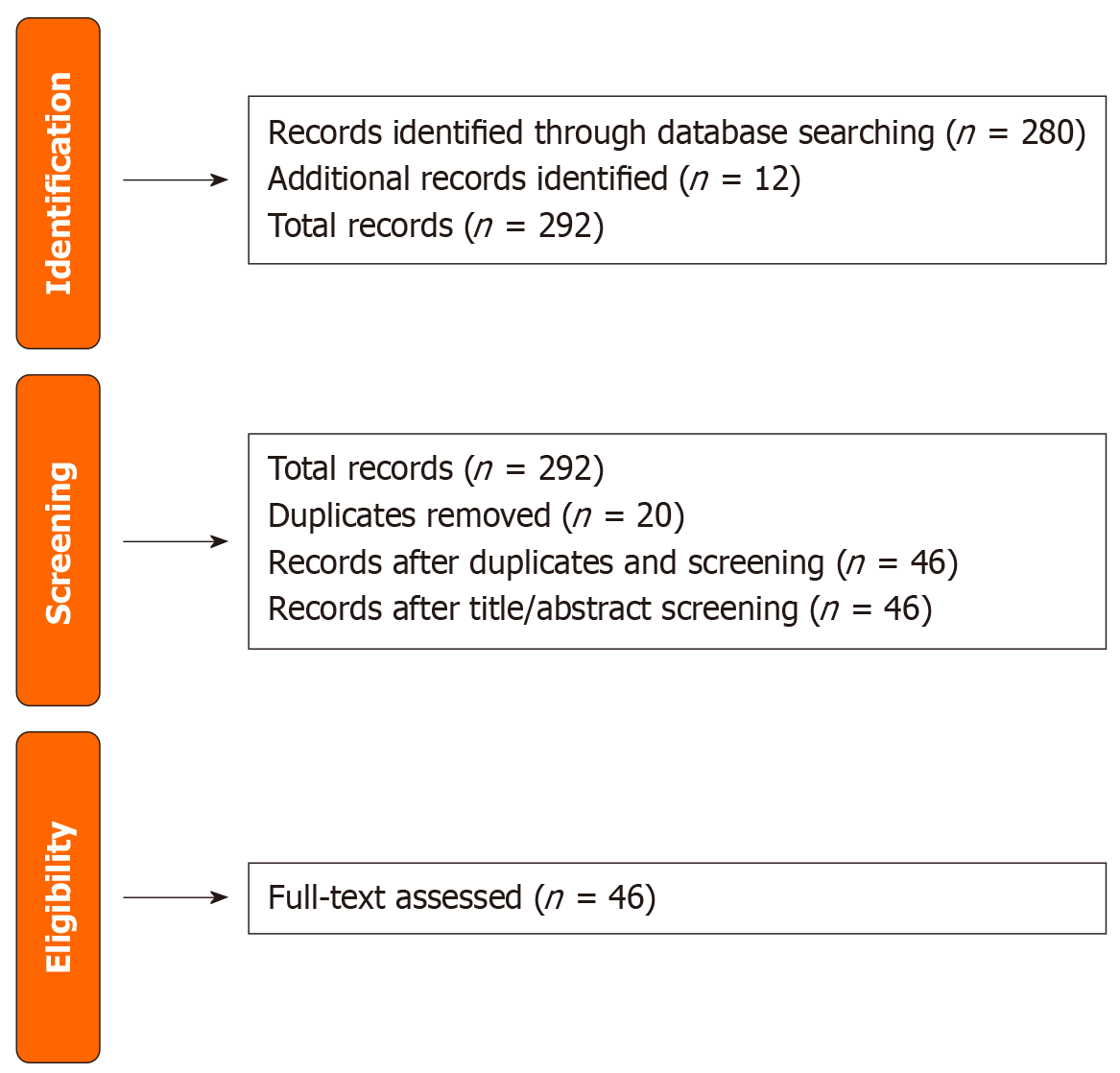

Initially, 280 records were identified from various databases, supplemented by an additional 12 records obtained through manual searches, reference lists, grey literature, and expert consultations. After the removal of 20 duplicate records, 46 unique records remained for the title and abstract screening phase. This screening aimed to exclude studies that did not meet the basic inclusion criteria. The next step involved obtaining and assessing the full texts of these 46 articles for eligibility based on predefined criteria, including relevance, methodology, and quality of evidence. This systematic approach ensured a thorough and transparent selection process, enhancing the reliability and validity of the research findings. The selection process of this review is shown in Figure 1.

Post-operative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) is best understood as a multifactorial syndrome arising from the interaction of several theoretical frameworks. Though neuroinflammation, the GBA, oxidative stress, and disrupted neuroplasticity are individually important, their dynamic interplay is critical[9,10]. Systemic inflammation triggered by surgery can impair the gut barrier, leading to increased permeability and the release of inflammatory molecules that exacerbate neuroinflammation through the GBA[1,6]. Additionally, oxidative stress, resulting from an imbalance between free radicals and antioxidants, acts as a convergence point where inflammation and gut dysbiosis amplify damage to neurons[2,3]. The timing of these events disrupts the brain's ability to recover and adapt, contributing to the persistent cognitive deficits seen in POCD[11,12].

The gut microbiota plays a pivotal role in this communication by influencing the production of neurotransmitters and neurotrophic factors, which are critical for cognitive function.

Serotonin production: One of the most well-known neurotransmitters influenced by gut bacteria is serotonin, often referred to as the “happiness hormone”. Approximately 90% of the body’s serotonin is synthesized in the gut, where it is derived from the amino acid tryptophan. The presence and activity of certain gut bacteria can significantly affect the availability of tryptophan and its conversion to serotonin. SCFAs play a crucial role in this process. SCFAs, such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate, can enhance the production of serotonin by stimulating enterochromaffin cells in the gut to produce more of this neurotransmitter[3]. The serotonin produced in the gut can then influence brain function by interacting with the vagus nerve, which transmits signals directly to the brain, thereby impacting mood, cognition, and overall mental health[1].

BDNF expression: BDNF is another critical component influenced by gut microbiota. BDNF is essential for neuroplasticity, which is the brain's ability to adapt and reorganize itself, and is crucial for learning, memory, and cognitive resilience. SCFAs, particularly butyrate, have been shown to upregulate BDNF expression in the brain, enhancing cognitive functions and providing neuroprotective effects[6]. The interaction between gut bacteria and BDNF highlights the profound impact that gut health can have on brain function.

Microbial contributions to GBA and cognitive health: Akkermansia muciniphila (A. kkermansia) is a keystone bacterium in the gut microbiota that plays a crucial role in maintaining gut barrier integrity, producing SCFAs, and modulating neurotransmitter levels, all of which are essential for cognitive and brain health. This bacterium strengthens the gut barrier by promoting mucin production, preventing pro-inflammatory molecules from entering the bloodstream and triggering inflammation[7]. Additionally, it facilitates the production of SCFAs (butyrate, acetate, and propionate) through the fermentation of dietary fibers. These SCFAs maintain the blood-brain barrier’s integrity, modulate inflammation, and serve as energy sources for enterocytes[6]. A. muciniphila also enhances neurotransmitter production by increasing the availability of tryptophan, a precursor for serotonin synthesis. SCFAs stimulate enterochromaffin cells to produce serotonin, which is vital for mood regulation and cognitive function[3]. Furthermore, the bacterium increases levels of BDNF through butyrate production, promoting neuroplasticity, learning, and memory[1]. By combining these mechanisms—gut barrier reinforcement, SCFA production, and neurotransmitter modulation—A. muciniphila links gut health to cognitive resilience. Moreover, A. muciniphila helps restore metabolite balance in the gut. By maintaining gut barrier integrity and reducing inflammation, it modulates tryptophan and its metabolites, such as kynurenic acid, influencing cognitive outcomes. Enhanced SCFA production positively affects the GBA, promoting beneficial metabolite synthesis and reducing neuroinflammation[8]. This modulation of metabolite levels is crucial for maintaining cognitive health and preventing disorders like POCD.

Gut metabolites are bioactive compounds produced by gut microbiota that have profound effects on cognitive outcomes. These metabolites include SCFAs, neurotransmitters, and various other compounds that can influence brain function and cognitive health.

Tryptophan and serotonin: Tryptophan is an essential amino acid that serves as a precursor for serotonin synthesis. The availability of tryptophan in the gut and its subsequent conversion to serotonin is significantly influenced by gut microbiota. Disruptions in gut microbiota can lead to altered tryptophan metabolism, impacting serotonin levels and, consequently, cognitive function[13]. Tryptophan is metabolized through multiple pathways in the gut, with one significant pathway being the conversion to kynurenine, which can then lead to the production of kynurenic acid and quinolinic acid, both of which have notable effects on the brain.

Kynurenic acid: Kynurenic acid, a metabolite produced from tryptophan through the kynurenine pathway, has neuroprotective properties under normal conditions. However, its overproduction can lead to neurotoxic effects and cognitive impairments. Elevated levels of kynurenic acid have been associated with cognitive decline and neuroinflammation, as observed in conditions like POCD[14]. The balance between beneficial and detrimental effects of kynurenic acid is delicate and can be influenced by gut microbiota composition.

Microbiota-based interventions in post-operative cognitive dysfunction: POCD is a significant clinical issue, particularly affecting elderly patients after surgery. The underlying mechanisms of POCD are multifaceted, involving neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and disruptions in the gut microbiota, known as gut dysbiosis[12]. Gut dysbiosis can exacerbate neuroinflammation post-surgery by increasing the permeability of the gut barrier, leading to the translocation of pro-inflammatory molecules into the bloodstream, thereby reaching the brain and contributing to neuroinflammatory responses[9].

Gut microbial community has been identified as a key player in maintaining gut health and mitigating these disruptions. This bacterium enhances gut barrier function by promoting the production of mucus and tight junction proteins, which are crucial for maintaining the integrity of the gut lining[15]. By restoring the gut barrier, gut- associated microbes reduces the translocation of harmful substances that can trigger systemic inflammation and subsequent neuroinflammation. Furthermore, microbes inhabiting the gut produces SCFAs, such as butyrate, which have anti-inflammatory properties. SCFAs can cross the blood-brain barrier and exert protective effects against neuroinflammation and oxidative stress, both of which are implicated in POCD[6]. Additionally, by modulating tryptophan metabolism, these microbes can influence the kynurenine pathway, reducing the production of neurotoxic metabolites such as quinolinic acid while gut-microbiota modulating therapies alleviates cognitive dysfunction and prevents synaptic reduction in the hippocampus of Sprague-Dawley (SD) mice by inhibiting microglial activation and synaptic engulfment, increasing serum acetate and butanoic acid levels[16]. SCFAs pretreatment inhibits microglial synaptic engulfment and prevents neuronal synaptic loss following lipopolysaccharides (LPS) stimulation. Supplementation with commensal bacteria may prevent SD-induced cognitive dysfunction by increasing SCFAs production and maintaining microglial homeostasis[7]. A. muciniphila, enriched by metformin, improves cognitive function in aged mice by reducing the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). It modulates inflammation-related pathways and enhances gut health, reducing systemic and neuroinflammation, and balancing metabolite production. Future clinical studies are needed to confirm these benefits and develop effective probiotic treatments incorporating A. muciniphila for cognitive recovery in post-operative patients[7].

Post-operative dysbiosis refers to the disruption of normal gut microbiota composition following surgical interventions. Multiple perioperative factors—such as general anesthesia, opioid use, stress, perioperative fasting, and antibiotic administration—are known to reduce microbial diversity and diminish the abundance of beneficial commensals like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium[11,17].

This microbial imbalance can increase intestinal permeability, allowing the translocation of microbial products such as LPS into systemic circulation[9]. These LPS molecules can cross the blood-brain barrier and activate microglia, resulting in neuroinflammation—an important pathophysiological mechanism behind POCD[1,12].

Moreover, post-operative dysbiosis often leads to a significant reduction in SCFA production, particularly butyrate, which plays a vital role in maintaining gut epithelial health and modulating systemic immunity[6]. This SCFA depletion compromises mucosal integrity and further amplifies inflammatory signaling both locally and centrally[3].

Restorative strategies, including the use of prebiotics, probiotics, and fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), are being actively explored to re-establish microbial homeostasis. These interventions aim to reduce neuroinflammation, enhance SCFA production, and improve post-operative recovery and cognitive outcomes. Evidence from a meta-analysis by Kocsis et al[17] demonstrates that probiotics improve gut microbial composition and metabolic health in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, supporting the broader concept that probiotics can enhance microbial balance and may have therapeutic relevance in postoperative recovery[7,17].

Beyond microbial diversity loss and reduced SCFA production, recent studies emphasize endotoxemia as a key mechanistic link between perioperative gut dysbiosis and adverse neurological outcomes. Surgical stress and perioperative interventions can amplify gut-derived endotoxemia, further linking dysbiosis to postoperative cognitive risk. Surgery-induced barrier disruption allows LPS and other microbial metabolites to leak into systemic circulation, triggering systemic inflammation and neuroimmune activation. Circulating LPS can also comprise blood-brain barrier integrity, facilitating neuroinflammation. Elevated endotoxin levels have been associated with impaired hippocampal function and worsening cognitive outcomes following anesthesia and surgery. These findings highlight endotoxemia as a critical mediator between perioperative gut microbiota changes and neurocognitive complications, underscoring the need for perioperative strategies to preserve microbial diversity and gut barrier integrity[9,11,18].

While A. muciniphila plays a central role in maintaining gut barrier integrity and cognitive health, several other commensal bacteria significantly influence postoperative and disease-associated neurocognitive outcomes. Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species enhance gut epithelial function, modulate immune responses, and produce neuroactive metabolites such as gamma-aminobutyric acid, contributing to improved stress resilience and memory function[6,10,19,20]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, a major butyrate producer, supports intestinal homeostasis and exerts potent anti-inflammatory effects, indirectly reducing neuroinflammation[6]. Streptococcus thermophilus, widely used in probiotic formulations such as VSL#3, enhances SCFA production and improves gut-brain communication, particularly in the perioperative setting[19]. Together, these taxa illustrate that cognitive outcomes are shaped by a broader microbial network rather than a single keystone species, emphasizing the need for multi-strain or community-level microbiota-targeted interventions.

The GBA—a bidirectional communication network linking the gut microbiota with the central nervous system—has become central to understanding the interplay between gut health and cognitive function. Among the diverse microbial species, A. muciniphila, a gram-negative, anaerobic bacterium, plays a pivotal role in maintaining intestinal barrier integrity, regulating immune responses, and influencing metabolic processes. There is a growing need to explore the impact of both overall gut microbial communities and A. muciniphila on cognitive function across various diseases, including metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative conditions, psychiatric illnesses, autoimmune diseases, and cancer-related cognitive impairments.

Gut microbiota, liver disease, and hepatic encephalopathy: The gut-liver-brain axis plays a key role in linking microbial imbalance to hepatic and cognitive dysfunction. In patients with liver disease, dysbiosis reduces beneficial SCFA-producing bacteria and allows overgrowth of pathogenic taxa, leading to increased intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation. LPS and other endotoxins enter the portal circulation, triggering systemic inflammation and impairing hepatic detoxification capacity. Gut microbes also contribute to excessive ammonia production, which, in the context of reduced hepatic clearance, crosses the blood–brain barrier and induces astrocyte swelling, neuroinflammation, and cognitive decline characteristic of hepatic encephalopathy.

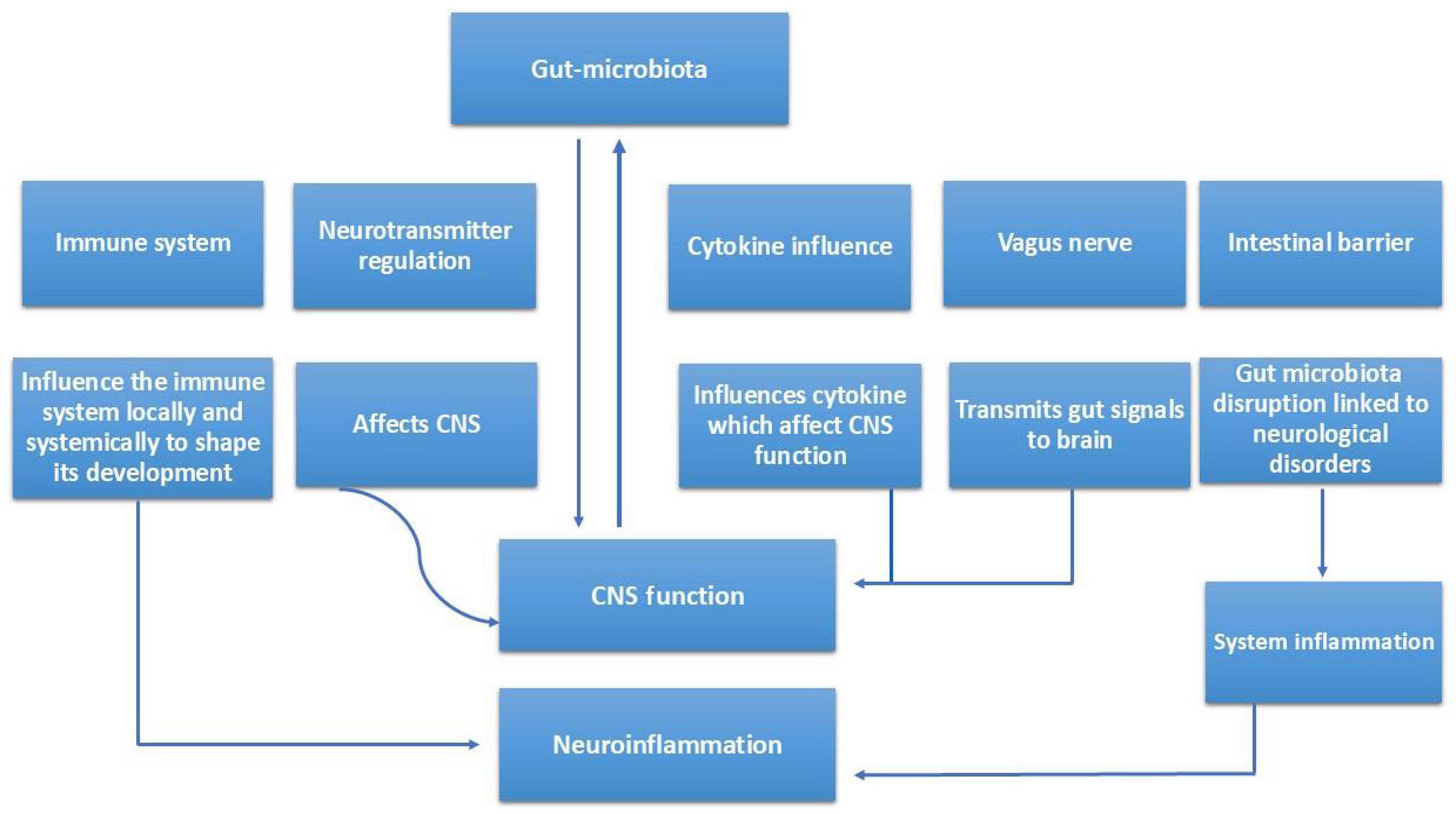

Perioperative factors—including surgical stress, fasting, opioids, and broad-spectrum antibiotics—further disrupt gut microbial diversity, exacerbating endotoxemia and increasing postoperative neurocognitive risk in patients with liver dysfunction. Microbiota-targeted strategies such as probiotics, prebiotics, and FMT show promise in restoring gut-liver-brain homeostasis, reducing toxin burden, and improving cognition[18,21,22]. The potential mechanisms linking gut microbiota with the central nervous system function and neuroinflammation are illustrated in Figure 2.

The GBA and A. muciniphila: The GBA operates via neural, endocrine, immune, and microbial pathways. Gut microbes influence this axis through mucin regulation, immune modulation, and metabolite production. According to Derrien et al[5], gut microbiota enhances mucin production, strengthening the intestinal barrier and preventing systemic inflammation. A. muciniphila also limits the leakage of LPS into the bloodstream, reducing systemic and neuroinflammation[5,18]. Furthermore, it produces SCFAs such as acetate and butyrate, which maintain the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and exert neuroprotective effects[8]. These pathways form the basis of A. muciniphila’s cognitive benefits.

Cognitive benefits in metabolic disorders: Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus: Obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus contribute to cognitive impairments through insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and systemic inflammation. Microbiota-based interventions have shown promise in mitigating these effects. Studies by Everard et al[15] and Amar et al[23] found that microbiota supplementation in high-fat-diet-induced obese mice reduced fasting glucose and insulin levels, improving cognitive outcomes by enhancing insulin sensitivity. Moreover, Cani et al[18] demonstrated that lowering LPS levels curbs neuroinflammatory cascades linked to hippocampal dysfunction. In human diabetic patients, clinical trials observed improvements in executive function and memory, linked to reduced oxidative stress[24].

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is linked to cognitive decline via ammonia accumulation and chronic inflammation. Gut microbiota supplementation has been found to enhance bile acid metabolism, reducing neurotoxicity[25]. According to Delzenne et al[21], gut microbes also reduce neurotoxin levels such as ammonia. Patients with corrected dysbiosis, particularly those with improved A. muciniphila levels, showed better working memory and attention[21,22].

Neurodegenerative diseases: Alzheimer’s disease (AD): Altered gut microbiota, including reduced A. muciniphila, is an emerging early marker of AD. SCFAs produced by gut bacteria activate microglia, aiding in amyloid-beta clearance[26]. Supplementation of A. muciniphila has been shown to lower neuroinflammatory markers like tumour necrosis factor alpha and IL-6 in AD mouse models[27]. Clinical studies also link higher commensal bacteria levels with better cognitive scores in AD patients[28].

Parkinson’s disease: Gut dysbiosis in Parkinson’s disease (PD) often precedes motor and cognitive symptoms. Gut modulation therapies have shown that A. muciniphila protects dopaminergic neurons, improving motor and cognitive symptoms[29,30]. It also modulates neuroinflammation by reducing gut-derived inflammatory signals. Human studies report enhanced verbal memory and cognitive flexibility in PD patients with higher A. muciniphila levels[31].

Psychiatric disorders: Depression is often linked to gut dysbiosis and increased gut permeability. Gut-targeted therapies enhance neurotransmitter regulation and immune balance. SCFAs influence the synthesis of serotonin and dopamine precursors[32], while reducing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis hyperactivation and systemic inflammation[33]. A meta-analysis by Luo et al[34] noted that individuals with depression typically show reduced gut microbial diversity, and probiotic use improves mood and cognitive symptoms.

Schizophrenia: Patients with schizophrenia exhibit reduced A. muciniphila levels. Though direct evidence remains limited, its known effects on gut integrity and neuroinflammation suggest therapeutic potential[35].

Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases: In multiple sclerosis (MS), gut dysbiosis worsens neuroinflammation. Next-generation microbial therapies enhance myelin regeneration and reduce inflammatory cytokines, leading to better spatial memory in animal models[36]. Ongoing human trials aim to evaluate A. muciniphila’s role in improving cognitive outcomes in MS[37].

Rheumatoid arthritis-related cognitive issues stem from chronic inflammation. Gut microbial balance helps reduce joint and systemic inflammation, impacting cognitive domains[38] According to Braniste et al[39], A. muciniphila supports BBB integrity, shielding the brain from LPS-induced damage.

Chemotherapy-induced cognitive impairment, or "chemo brain", is increasingly tied to gut microbiota disruptions. Supplementation helps restore microbial diversity and lower systemic inflammation, thus improving cognition[40]. Pilot studies show that A. muciniphila supplementation enhanced memory and processing speed in cancer patients[41].

Study conducted by Jiang et al[19], underscored the critical role of specific bacteria in maintaining gut-brain health. By using VSL#3 in his study, it highlights the therapeutic potential of probiotics in preventing and managing postoperative cognitive dysfunction, particularly in aging populations. VSL#3 is a high-potency probiotic formulation containing a combination of eight bacterial strains: Lactobacillus (L. acidophilus, L. plantarum, L. paracasei, L. delbrueckii spp. bulgaricus), Bifidobacterium (B. breve, B. longum, B. infantis), and Streptococcus thermophilus. In the study, administering VSL#3 effectively restored the balance of disrupted gut microbiota caused by anesthesia and surgery in aged mice. This probiotic intervention mitigated cognitive deficits, such as memory impairments, by reducing gut permeability, decreasing systemic inflammation, and promoting the production of neuroprotective metabolites. These findings highlight the potential of VSL#3 in preserving gut-brain health and preventing postoperative cognitive dysfunction in aging populations[19]. A randomized control trial by Zhang et al[20] tested the probiotic Peifeikang (Live Combined Bifidobacterium) containing Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus acidophilus, and Streptococcus faecalis, each with ≥ 1.0 × 107 CFU per 210 mg capsule. Participants took four capsules (840 mg) twice daily, starting one day before and continuing for six days post-surgery. The study aimed to evaluate probiotics' efficacy in reducing POCD in elderly orthopedic surgery patients by maintaining gut microbiota balance (Table 1).

| Cognitive disorder | Key gut microbiota changes | Mechanistic pathways | Impact on cognition | Microbiota-targeted interventions | Ref. |

| Post-operative cognitive dysfunction | ↓ A. muciniphila, ↓ Lactobacillus, ↓ Bifidobacterium; dysbiosis post-surgery, anesthesia, antibiotics | ↑ Gut permeability → systemic LPS → neuroinflammation; ↓ SCFAs → BBB compromise; microglial activation & synaptic loss | Memory & attention deficits post-surgery; delayed recovery | VSL#3, Peifeikang probiotics; SCFA supplementation; gut barrier restoration | [7,9,12,16,20] |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Dysbiosis: ↑ pathogenic taxa, ↓ SCFA producers | ↑ Ammonia & endotoxemia → systemic & neuroinflammation; impaired hepatic detoxification | Confusion, poor executive function | Probiotics, prebiotics, FMT | [18,21,22,45] |

| Obesity & type 2 diabetes | ↓ A. muciniphila, ↑ Gram-negative bacteria | Endotoxemia (LPS) → insulin resistance; hippocampal dysfunction | Cognitive decline, poor executive function | A. muciniphila supplementation; dietary modulation | [1,18,23,24] |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | Altered bile acid metabolism; ↓ A. muciniphila | Ammonia & bile acid dysregulation; chronic inflammation | Memory & attention deficits | Probiotics; bile acid-targeted therapies | [21,22,25] |

| Alzheimer’s disease | ↓ SCFA-producing bacteria; ↓ A. muciniphila | Microglia activation; ↑ TNF-α, IL-6 | Memory loss; cognitive decline | A. muciniphila, multi-strain probiotics, FMT | [26-28] |

| Parkinson’s disease | Dysbiosis; ↓ SCFA producers; ↓ A. muciniphila | Gut inflammation → α-synuclein aggregation; gut–brain immune signaling | Motor & cognitive symptoms | Probiotics, diet, FMT | [29-31] |

| Depression | ↓ Microbial diversity; altered Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio | SCFAs regulate serotonin & dopamine; hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation | Low mood; impaired cognition | Psychobiotics, probiotics, fiber | [32-34] |

| Schizophrenia | ↓ A. muciniphila; dysbiosis | Barrier dysfunction; systemic inflammation; neurotransmitter disruption | Cognitive impairment; psychosis | Early microbiota therapy research | [35] |

| Multiple sclerosis | Dysbiosis; ↓ SCFA producers | Immune dysregulation → demyelination; ↑ cytokines | Poor memory; cognitive decline | Next-gen probiotics; A. muciniphila | [36,37] |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | Altered gut microbiome; ↓ A. muciniphila | Chronic inflammation; compromised BBB | Brain fog; fatigue | Probiotic therapies (research) | [38,39] |

| Chemo brain (cancer therapy cognitive impairment) | Severe microbiota disruption post-chemo | LPS & cytokines → neuroinflammation; SCFA depletion | Memory loss; slower processing | A. muciniphila, probiotics, FMT | [40,41] |

The therapeutic potential of microbial interventions for cognitive support as a probiotic for cognitive health is an area of growing interest. Probiotics are live microorganisms that confer health benefits to the host when administered in adequate amounts. The beneficial effects of gut flora on gut health and its implications for cognitive function make it a promising candidate for therapeutic applications. (1) Probiotic Applications: Studies have demonstrated that A. muciniphila can improve gut barrier function, reduce inflammation, and modulate gut microbiota composition. These effects can translate into improved cognitive outcomes by enhancing neurotransmitter synthesis and reducing neuroinflammation. The administration of A. muciniphila has shown promise in preclinical models, where it improved metabolic profiles and cognitive performance[15]. The bacterium’s ability to produce SCFAs and other beneficial metabolites plays a significant role in its probiotic potential, as these compounds are known to support cognitive health by modulating the GBA; (2) Challenges: Despite the promising preclinical findings, translating these results to human studies poses several challenges. Variability in human gut microbiota, differences in diet and lifestyle, and the complexity of human cognitive functions make it difficult to predict the exact effects of A. muciniphila in humans. Moreover, the safety and efficacy of long-term probiotic administration need thorough evaluation. The regulatory landscape for probiotics also presents challenges, as rigorous clinical trials are required to establish the therapeutic benefits and safety of probiotics in humans[42]; and (3) Opportunities: Advances in microbiome research and personalized medicine offer new opportunities for developing targeted probiotic therapies.

FMT as a therapeutic strategy: FMT is an emerging therapeutic intervention designed to restore gut microbial diversity by transferring stool from a healthy donor to a dysbiotic host. Originally established for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections, FMT has gained attention for its potential to modulate systemic inflammation, repair intestinal barrier function, and influence neurocognitive outcomes. Preclinical studies demonstrate that FMT can reduce LPS-mediated neuroinflammation, normalize SCFA levels, and improve synaptic plasticity in animal models of neurological disorders[43,44]. Early human studies suggest FMT may improve gut-brain communication and alleviate symptoms in conditions such as hepatic encephalopathy and PD, highlighting its potential as an adjunct therapy in surgery-related cognitive impairment[45,46].

While further randomized trials are needed to confirm efficacy and optimize donor selection, delivery route, and long-term safety, FMT represents a promising tool for resetting the gut microbiome and mitigating neuroinflammatory cascades implicated in postoperative cognitive dysfunction.

Future research should focus on clinical trials to confirm the efficacy and safety of intestinal microbiota, potentially revolutionizing cognitive health management through microbiome-based therapies. The development of targeted interventions that modulate the gut microbiota to enhance cognitive function represents a promising frontier in medical research. These future studies should explore optimal dosages, treatment durations, and specific patient populations that would benefit most from gut microbiota- modulating therapies. Additionally, investigating the synergistic effects of microbiota- derived intervations with other probiotics, prebiotics, or dietary interventions could lead to more comprehensive strategies for promoting cognitive health and preventing cognitive decline.

Certain beneficial microbes plays a crucial role in cognitive health through the GBA. This keystone bacterium helps maintain gut barrier integrity, modulate immune responses, and produce beneficial metabolites like SCFAs, which collectively enhance cognitive functions. It shows promise in mitigating cognitive dysfunction in diseases such as hepatic encephalopathy, AD, type 2 diabetes, and inflammatory bowel diseases by reducing neuroinflammation and regulating neurotransmitters like serotonin and BDNF.

Additionally, notably species such as A. muciniphila is effective in addressing POCD. By restoring gut health, mitigating neuroinflammation, and balancing metabolite production, it offers a promising avenue for supporting cognitive recovery in post-operative patients. Its ability to reduce systemic inflammation and enhance gut-brain communication makes it a valuable therapeutic candidate for improving cognitive outcomes after surgery.

This exploration highlights the deep interconnectedness of gut and brain health, emphasizing the potential of commensal bacteria in enhancing cognitive resilience and well-being. Future research in this area is crucial for translating these findings into clinical applications and developing effective treatments for cognitive disorders.

The authors acknowledge the academic support of their respective departments at AIIMS New Delhi.

| 1. | Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:701-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2403] [Cited by in RCA: 3143] [Article Influence: 224.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Fekete M, Lehoczki A, Major D, Fazekas-Pongor V, Csípő T, Tarantini S, Csizmadia Z, Varga JT. Exploring the Influence of Gut-Brain Axis Modulation on Cognitive Health: A Comprehensive Review of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Symbiotics. Nutrients. 2024;16:789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stasi C, Sadalla S, Milani S. The Relationship Between the Serotonin Metabolism, Gut-Microbiota and the Gut-Brain Axis. Curr Drug Metab. 2019;20:646-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cryan JF, O'Mahony SM. The microbiome-gut-brain axis: from bowel to behavior. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:187-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 606] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Derrien M, Vaughan EE, Plugge CM, de Vos WM. Akkermansia muciniphila gen. nov., sp. nov., a human intestinal mucin-degrading bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1469-1476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1124] [Cited by in RCA: 1545] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 6. | Fung TC, Olson CA, Hsiao EY. Interactions between the microbiota, immune and nervous systems in health and disease. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:145-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 980] [Cited by in RCA: 1411] [Article Influence: 156.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Passel MW, Kant R, Zoetendal EG, Plugge CM, Derrien M, Malfatti SA, Chain PS, Woyke T, Palva A, de Vos WM, Smidt H. The genome of Akkermansia muciniphila, a dedicated intestinal mucin degrader, and its use in exploring intestinal metagenomes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Plovier H, Everard A, Druart C, Depommier C, Van Hul M, Geurts L, Chilloux J, Ottman N, Duparc T, Lichtenstein L, Myridakis A, Delzenne NM, Klievink J, Bhattacharjee A, van der Ark KC, Aalvink S, Martinez LO, Dumas ME, Maiter D, Loumaye A, Hermans MP, Thissen JP, Belzer C, de Vos WM, Cani PD. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med. 2017;23:107-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 967] [Cited by in RCA: 1583] [Article Influence: 158.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Terrando N, Rei Fidalgo A, Vizcaychipi M, Cibelli M, Ma D, Monaco C, Feldmann M, Maze M. The impact of IL-1 modulation on the development of lipopolysaccharide-induced cognitive dysfunction. Crit Care. 2010;14:R88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhu G, Zhao J, Zhang H, Chen W, Wang G. Probiotics for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Foods. 2021;10:1672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Liu F, Duan M, Fu H, Zhao G, Han Y, Lan F, Ahmed Z, Cao G, Li Z, Ma D, Wang T. Orthopedic Surgery Causes Gut Microbiome Dysbiosis and Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction in Prodromal Alzheimer Disease Patients: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. Ann Surg. 2022;276:270-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zywiel MG, Hurley RT, Perruccio AV, Hancock-Howard RL, Coyte PC, Rampersaud YR. Health economic implications of perioperative delirium in older patients after surgery for a fragility hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:829-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Clarke G, Grenham S, Scully P, Fitzgerald P, Moloney RD, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The microbiome-gut-brain axis during early life regulates the hippocampal serotonergic system in a sex-dependent manner. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:666-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1388] [Article Influence: 106.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Ostapiuk A, Urbanska EM. Kynurenic acid in neurodegenerative disorders-unique neuroprotection or double-edged sword? CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022;28:19-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Everard A, Belzer C, Geurts L, Ouwerkerk JP, Druart C, Bindels LB, Guiot Y, Derrien M, Muccioli GG, Delzenne NM, de Vos WM, Cani PD. Cross-talk between Akkermansia muciniphila and intestinal epithelium controls diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9066-9071. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2639] [Cited by in RCA: 3487] [Article Influence: 268.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Li N, Tan S, Wang Y, Deng J, Wang N, Zhu S, Tian W, Xu J, Wang Q. Akkermansia muciniphila supplementation prevents cognitive impairment in sleep-deprived mice by modulating microglial engulfment of synapses. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2252764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kocsis T, Molnár B, Németh D, Hegyi P, Szakács Z, Bálint A, Garami A, Soós A, Márta K, Solymár M. Probiotics have beneficial metabolic effects in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Sci Rep. 2020;10:11787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Fava F, Knauf C, Burcelin RG, Tuohy KM, Gibson GR, Delzenne NM. Selective increases of bifidobacteria in gut microflora improve high-fat-diet-induced diabetes in mice through a mechanism associated with endotoxaemia. Diabetologia. 2007;50:2374-2383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1237] [Cited by in RCA: 1310] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Jiang XL, Gu XY, Zhou XX, Chen XM, Zhang X, Yang YT, Qin Y, Shen L, Yu WF, Su DS. Intestinal dysbacteriosis mediates the reference memory deficit induced by anaesthesia/surgery in aged mice. Brain Behav Immun. 2019;80:605-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang X, Chen Y, Tang Y, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Su D. Efficiency of probiotics in elderly patients undergoing orthopedic surgery for postoperative cognitive dysfunction: a study protocol for a multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2023;24:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Delzenne NM, Knudsen C, Beaumont M, Rodriguez J, Neyrinck AM, Bindels LB. Contribution of the gut microbiota to the regulation of host metabolism and energy balance: a focus on the gut-liver axis. Proc Nutr Soc. 2019;78:319-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Boursier J, Mueller O, Barret M, Machado M, Fizanne L, Araujo-Perez F, Guy CD, Seed PC, Rawls JF, David LA, Hunault G, Oberti F, Calès P, Diehl AM. The severity of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with gut dysbiosis and shift in the metabolic function of the gut microbiota. Hepatology. 2016;63:764-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 763] [Cited by in RCA: 1114] [Article Influence: 111.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Amar J, Chabo C, Waget A, Klopp P, Vachoux C, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Smirnova N, Bergé M, Sulpice T, Lahtinen S, Ouwehand A, Langella P, Rautonen N, Sansonetti PJ, Burcelin R. Intestinal mucosal adherence and translocation of commensal bacteria at the early onset of type 2 diabetes: molecular mechanisms and probiotic treatment. EMBO Mol Med. 2011;3:559-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 637] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hu L, Luo M, Huang H, Wu L, Ouyang W, Tong J, Le Y. Perioperative probiotics attenuates postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trial. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:1037904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Le Roy T, Llopis M, Lepage P, Bruneau A, Rabot S, Bevilacqua C, Martin P, Philippe C, Walker F, Bado A, Perlemuter G, Cassard-Doulcier AM, Gérard P. Intestinal microbiota determines development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Gut. 2013;62:1787-1794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 601] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yang J, Liang J, Hu N, He N, Liu B, Liu G, Qin Y. The Gut Microbiota Modulates Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease: Elucidating Crucial Factors and Mechanistic Underpinnings. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30:e70091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhuang Z, Yang R, Wang W, Qi L, Huang T. Associations between gut microbiota and Alzheimer's disease, major depressive disorder, and schizophrenia. J Neuroinflammation. 2020;17:288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zhang Y, Geng R, Tu Q. Gut microbial involvement in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. Aging (Albany NY). 2021;13:13359-13371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Qian Y, Yang X, Xu S, Wu C, Song Y, Qin N, Chen SD, Xiao Q. Alteration of the fecal microbiota in Chinese patients with Parkinson's disease. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;70:194-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 40.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Heintz-Buschart A, Pandey U, Wicke T, Sixel-Döring F, Janzen A, Sittig-Wiegand E, Trenkwalder C, Oertel WH, Mollenhauer B, Wilmes P. The nasal and gut microbiome in Parkinson's disease and idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder. Mov Disord. 2018;33:88-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 421] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Unger MM, Spiegel J, Dillmann KU, Grundmann D, Philippeit H, Bürmann J, Faßbender K, Schwiertz A, Schäfer KH. Short chain fatty acids and gut microbiota differ between patients with Parkinson's disease and age-matched controls. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2016;32:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 598] [Cited by in RCA: 878] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Foster JA, Rinaman L, Cryan JF. Stress & the gut-brain axis: Regulation by the microbiome. Neurobiol Stress. 2017;7:124-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 790] [Article Influence: 87.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kelly JR, Borre Y, O' Brien C, Patterson E, El Aidy S, Deane J, Kennedy PJ, Beers S, Scott K, Moloney G, Hoban AE, Scott L, Fitzgerald P, Ross P, Stanton C, Clarke G, Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Transferring the blues: Depression-associated gut microbiota induces neurobehavioural changes in the rat. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;82:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 849] [Cited by in RCA: 1219] [Article Influence: 121.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Luo Y, Zeng B, Zeng L, Du X, Li B, Huo R, Liu L, Wang H, Dong M, Pan J, Zheng P, Zhou C, Wei H, Xie P. Gut microbiota regulates mouse behaviors through glucocorticoid receptor pathway genes in the hippocampus. Transl Psychiatry. 2018;8:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kang EJ, Cha MG, Kwon GH, Han SH, Yoon SJ, Lee SK, Ahn ME, Won SM, Ahn EH, Suk KT. Akkermansia muciniphila improve cognitive dysfunction by regulating BDNF and serotonin pathway in gut-liver-brain axis. Microbiome. 2024;12:181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cekanaviciute E, Yoo BB, Runia TF, Debelius JW, Singh S, Nelson CA, Kanner R, Bencosme Y, Lee YK, Hauser SL, Crabtree-Hartman E, Sand IK, Gacias M, Zhu Y, Casaccia P, Cree BAC, Knight R, Mazmanian SK, Baranzini SE. Gut bacteria from multiple sclerosis patients modulate human T cells and exacerbate symptoms in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:10713-10718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 762] [Article Influence: 84.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Tremlett H, Bauer KC, Appel-Cresswell S, Finlay BB, Waubant E. The gut microbiome in human neurological disease: A review. Ann Neurol. 2017;81:369-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 382] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Li J, Fan R, Zhang Z, Zhao L, Han Y, Zhu Y, Duan JA, Su S. Role of gut microbiota in rheumatoid arthritis: Potential cellular mechanisms regulated by prebiotic, probiotic, and pharmacological interventions. Microbiol Res. 2025;290:127973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Braniste V, Al-Asmakh M, Kowal C, Anuar F, Abbaspour A, Tóth M, Korecka A, Bakocevic N, Ng LG, Kundu P, Gulyás B, Halldin C, Hultenby K, Nilsson H, Hebert H, Volpe BT, Diamond B, Pettersson S. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6:263ra158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in RCA: 1848] [Article Influence: 168.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 40. | Derosa L, Routy B, Thomas AM, Iebba V, Zalcman G, Friard S, Mazieres J, Audigier-Valette C, Moro-Sibilot D, Goldwasser F, Silva CAC, Terrisse S, Bonvalet M, Scherpereel A, Pegliasco H, Richard C, Ghiringhelli F, Elkrief A, Desilets A, Blanc-Durand F, Cumbo F, Blanco A, Boidot R, Chevrier S, Daillère R, Kroemer G, Alla L, Pons N, Le Chatelier E, Galleron N, Roume H, Dubuisson A, Bouchard N, Messaoudene M, Drubay D, Deutsch E, Barlesi F, Planchard D, Segata N, Martinez S, Zitvogel L, Soria JC, Besse B. Intestinal Akkermansia muciniphila predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 2022;28:315-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 494] [Article Influence: 123.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhu X, Shen J, Feng S, Huang C, Wang H, Huo F, Liu H. Akkermansia muciniphila, which is enriched in the gut microbiota by metformin, improves cognitive function in aged mice by reducing the proinflammatory cytokine interleukin-6. Microbiome. 2023;11:120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hill C, Guarner F, Reid G, Gibson GR, Merenstein DJ, Pot B, Morelli L, Canani RB, Flint HJ, Salminen S, Calder PC, Sanders ME. Expert consensus document. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:506-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4055] [Cited by in RCA: 6018] [Article Influence: 501.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 43. | Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, Leong RWL, Connor S, Ng W, Paramsothy R, Xuan W, Lin E, Mitchell HM, Borody TJ. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1218-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 945] [Article Influence: 105.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 44. | Qiao CM, Zhou Y, Quan W, Ma XY, Zhao LP, Shi Y, Hong H, Wu J, Niu GY, Chen YN, Zhu S, Cui C, Zhao WJ, Shen YQ. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation from Aged Mice Render Recipient Mice Resistant to MPTP-Induced Nigrostriatal Degeneration Via a Neurogenesis-Dependent but Inflammation-Independent Manner. Neurotherapeutics. 2023;20:1405-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Bajaj JS, Kassam Z, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Liu E, Cox IJ, Kheradman R, Heuman D, Wang J, Gurry T, Williams R, Sikaroodi M, Fuchs M, Alm E, John B, Thacker LR, Riva A, Smith M, Taylor-Robinson SD, Gillevet PM. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial. Hepatology. 2017;66:1727-1738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 351] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 53.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Xue LJ, Yang XZ, Tong Q, Shen P, Ma SJ, Wu SN, Zheng JL, Wang HG. Fecal microbiota transplantation therapy for Parkinson's disease: A preliminary study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/