Published online Mar 5, 2026. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112615

Revised: September 25, 2025

Accepted: November 25, 2025

Published online: March 5, 2026

Processing time: 193 Days and 22.6 Hours

Overlapping pathophysiological mechanisms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, and functional dyspepsia often limit the symptom-based diagnosis precision. Additionally, the easy availability of over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors has increased the instances of self-diagnosis and self-treatment in the Indian population. Prolonged, unsupervised use of acid suppressants may reduce the treatment efficacy and increase the risk of adverse effects, such as infections and nutrient deficiencies. Therefore, a task force of 13 leading gastroenterologists under the Society for Clinical Gastroenterology reviewed the existing evidence to develop expert con

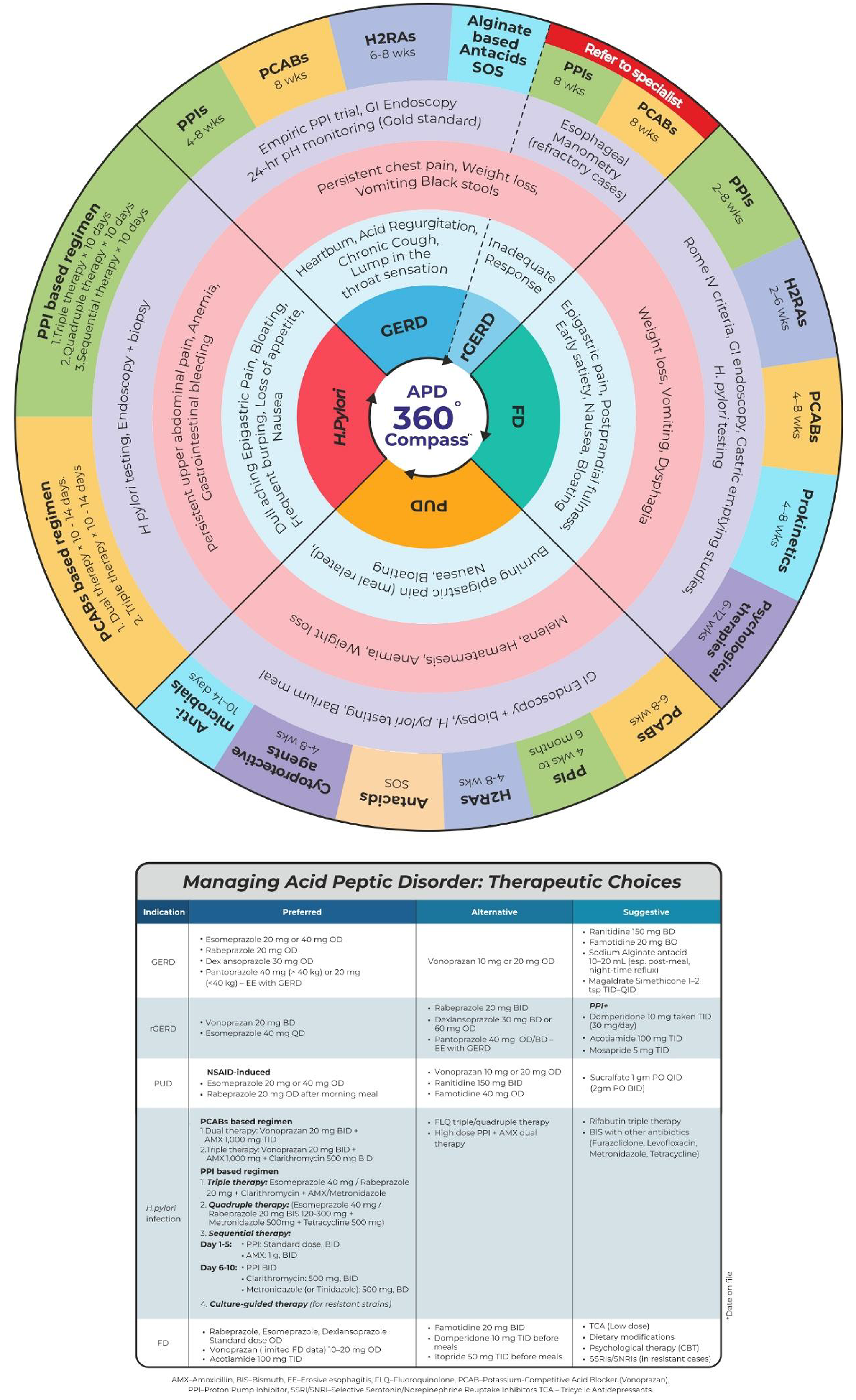

Core Tip: Overlapping mechanisms in gastroesophageal reflux disease, peptic ulcer, and functional dyspepsia often hinder accurate symptom-based diagnosis. In India, easy access to over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors has fuelled self-diagnosis and prolonged unsupervised use, which reduces treatment efficacy and increases risks of infections and nutrient deficiencies. To address this, a task force of 13 gastroenterologists under the Society for Clinical Gastroenterology reviewed evidence and developed 20 expert consensus statements. Through literature review and discussion, they proposed the acid peptic disorders 360° compass algorithm for distinguishing symptoms and guiding rational acid-suppressive therapy. This algorithm aims to improve timely diagnosis, treatment, and the patient’s quality of life.

- Citation: Sinha SK, Kochhar R, Rao KS, Yadav D, Ray S, Singh AP, Sethy PK, Mahajan R, Reddy DV, Sharma VM, Kumar A, Mishra A, Jain S, Swami OC, Patil D. Acid peptic disorder compass: An Indian expert consensus on comprehensive management. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2026; 17(1): 112615

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v17/i1/112615.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.112615

Acid peptic disorders (APD) encompass conditions such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and peptic ulcer disease (PUD), often related to Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), and represent a major global health burden[1,2]. Functional dyspepsia (FD) is another common gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that often co-exists with GERD due to their common pathophysiology[3]. Worldwide prevalence of dyspepsia is around 20%-30%, while in India, according to different studies, it widely varies between 7.6%-49%[4]. The reported prevalence of GERD is 8%-19% in India[5]. Precise diagnosis and prompt management of APD is crucial as it impacts the quality of life as well as work productivity of the patients[6].

Gastric acid suppression is the mainstay treatment for APD[7] and includes antacids, histamine-H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and potassium-competitive acid blockers (PCABs)[8]. PPIs are widely used as initial treatment for APD in clinical practices because of their favorable efficacy, tolerability, and easy availability[9]. Vonoprazan, a recent United States Food and Drug Administration-approved PCAB, is considered to have advantages over PPIs[10]. However, management of APDs is challenging due to overlapping symptoms[3,11], self-medication[12], refractory cases, long-term drug risks, regional healthcare disparities, and antibiotic resistance[1]. Throughout the years, the over-the-counter availability of PPIs and self-management has possibly delayed the treatment for a more serious underlying condition[12]. In addition, chronic use of PPIs without any supervision may lead to acute interstitial nephritis, hypergastrinemia, infections, and hyponatremia[13]. Selecting the right treatment for the right patient, comorbidities, patient adherence to medication regimens, and potential side effects pose additional challenges[14]. Moreover, rural healthcare in India faces compounded challenges due to geographical barriers, limited access to diagnostics, and a shortage of specialized care, often leading to delayed treatment[15]. These difficulties in managing APDs in India underscore the critical need to provide healthcare professionals with a comprehensive, evidence-based update on the APDs. Therefore, the APD 360° compass consensus study aims to provide evidence-based, consensus-driven clinical tool designed to streamline diagnosis, stratify patients, and guide personalized management of APDs through a structured algorithm and wheel diagram. The APD 360° compass offers a comprehensive, integrated overview of GERD, PUD, H. pylori infection, and FD to support clinical decision-making.

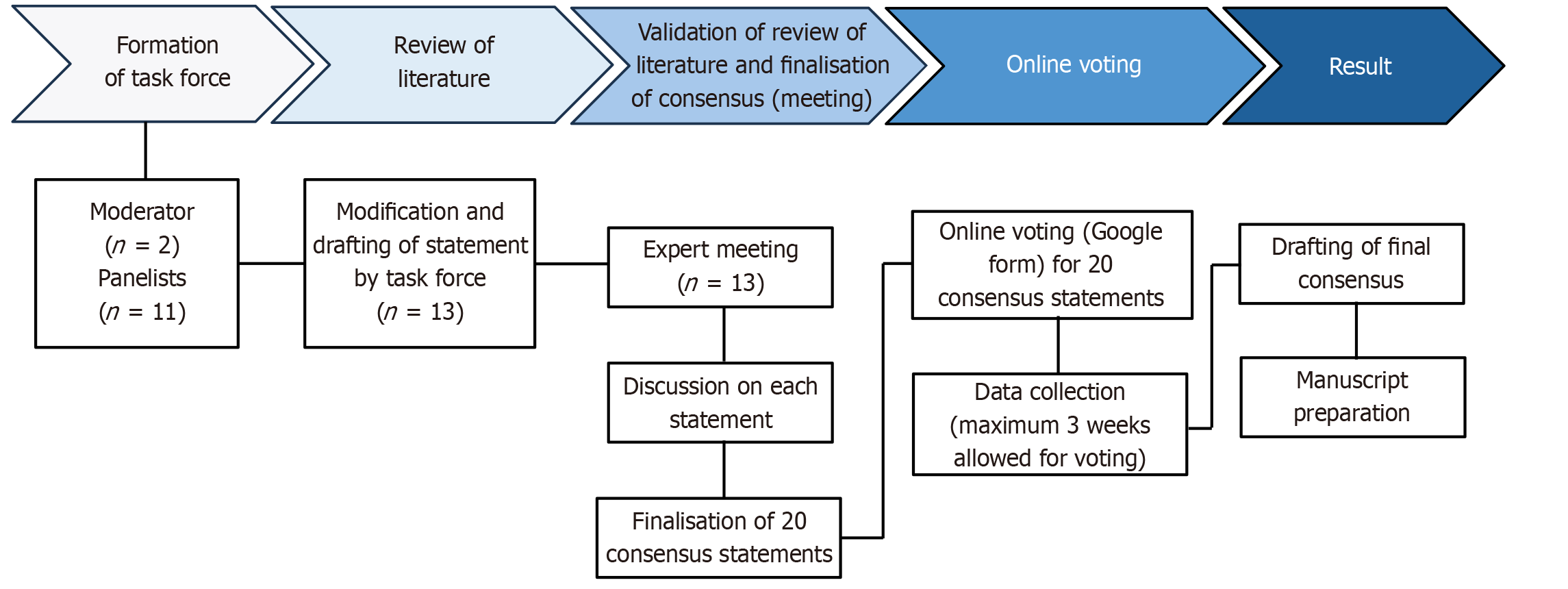

The development of the APD 360° compass was guided by a structured and evidence-based process led by a dedicated task force comprising 13 gastroenterologists under the aegis of the Society for Clinical Gastroenterology. This initiative aimed to formulate consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and management of APDs in the Indian population.

The task force members were selected based on their geographic representation across India, clinical expertise in APDs, and academic contributions to the field. Two senior gastroenterologists, identified for their subject-matter expertise and interest, served as moderators. The moderators defined the scope of the consensus, which included GERD, PUD, H. pylori infection, and FD. These categories were further subdivided into clinically relevant patient profiles such as refractory, recurrent, severe, and complicated cases.

A comprehensive literature search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar to identify relevant publications from 2010 to 2025. The search strategy targeted clinical trials, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, observational and comparative studies, and established clinical guidelines. Keywords included: Acid peptic disorders, acid suppression therapies (PPIs, H2RAs, PCABs), GERD management, peptic ulcer treatment, H. pylori eradication, FD, and Indian consensus guidelines. The moderators synthesized the evidence and guiding principles to draft 22 preliminary consensus statements across 11 subtopics, which were then assigned to respective task force members for in-depth review.

An in-person consensus meeting of approximately eight hours was conducted, during which each assigned subtopic was presented and discussed in detail. The task force deliberated on the evidence, assessed the validity of each statement, and revised it accordingly. This collaborative discussion resulted in the refinement of the original 22 statements to a final set of 20 consensus statements. Following the meeting, further discussions and clarifications were carried out via email to finalize the consensus statements before initiating the voting process.

The finalized statements were circulated via email to all task force members for voting using an online platform (Google forms). Each member was asked to rate the statements using a five-point Likert scale: A - accept completely; B - accept with some reservation; C - accept with major reservation; D - reject with some reservation; and E - reject with major reservation. A statement was considered to have achieved consensus if ≥ 80% of respondents rated it as either “accept completely” or “accept with some reservation” (i.e., A or B).

Voting responses were collated and analyzed. The manuscript was then drafted based on the finalized consensus statements and supporting evidence, followed by a comprehensive review and approval from all task force members prior to submission for publication. Figure 1 illustrates the consensus development process, including literature review, statement formulation, panel discussions, and voting. An APD management algorithm wheel has been prepared based on the guidelines and consensus recommendations that have examined different modalities of therapy for various APD.

The pharmacologic management of APDs has evolved significantly, with a clearer understanding of the pharmacodynamics and clinical utility of acid suppression agents. The recommended regimen for gastric acid suppression with H2RA, PPIs, PCABs, and prokinetics is shown in Table 1[16-28]. The H2RAs, though effective in mild cases, are limited by tachyphylaxis with prolonged use[29]. PPIs remain the cornerstone for most APDs due to their potent and sustained acid suppression; however, interpatient variability in metabolism and delayed onset can impact the outcomes[30,31]. The pharmacokinetic properties of the PPIs[32-34] are presented in Table 2.

| Ref. | GERD | Reflux/erosive esophagitis | NERD | PUD/H. pylori eradication |

| Bhatia et al[16], 2020; Yadlapati et al[17], 2022; Iwakiri et al[18], 2022; ZANTAC® SmPC[19] | Rabeprazole 20 mg OD | Vonoprazan 20 mg OD for 4 weeks (in mild condition) | Ranitidine 150 mg TID | Vonoprazan 20 mg BD (dual/triple therapy) |

| Iwakiri et al[18], 2022; NEXIUM SmPC[20]; PEPCID® SmPC[21] | Esomeprazole 20/40 mg OD | Vonoprazan 20 mg + prokinetics (in severe condition) for 8 weeks | Famotidine 20 mg BD | Esomeprazole 40 mg OD |

| Bhatia et al[16], 2020; Yadlapati et al[17], 2022; Farrell et al[22], 2017 | Dexlansoprazole 30 mg OD | Esomeprazole 40 mg OD | Esomeprazole 20 mg OD | Rabeprazole 20 mg OD (post-breakfast) for up to 4 weeks |

| PROTONIX SmPC[23]; DEXILANT SmPC[24]; Central Drugs Standard Control Organization Government of India[25] | Pantoprazole 40 mg OD | Dexlansoprazole 30/60 mg OD | Dexlansoprazole 30 mg OD | Ilaprazole 5-10 mg OD |

| ZANTAC® SmPC[19]; PEPCID® SmPC[21]; ACIPHEX® SmPC[26]; PRILOSEC SmPC[27] | Famotidine 40 mg OD | Ranitidine 150 mg QID | Rabeprazole 20 mg OD | Omeprazole 20 mg BD or 40 mg OD |

| ZANTAC® SmPC[19]; PEPCID® SmPC[21]; Central Drugs Standard Control Organization Government of India[28] | Ranitidine 150 mg BD | Famotidine 20/40 mg TID | Lafutidine 5-10 mg |

| Agents | Bioavailability (%) | Tmax (hour) | Cmax (mg/mL) | Protein binding (%) | T1/2 (hour) | pKa | AUC 0-24 (mg/hour/L) | V (L/kg) | CL (mL/minute) |

| Esomeprazole | 64-90 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 97 | 1-1.5 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 160-330 | 1.3-1.6 |

| Dexlansoprazole | - | 4-5 | - | 96 | 1-2 | 4.0 | - | - | - |

| Pantoprazole | 77 | 2-3 | 2.5 | 98 | 1-1.9 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 90-225 | 0.8-2.0 |

| Rabeprazole | 52 | 2-5 | 0.4 | 96.3 | 1-2 | 5.0 | 0.8 | - | 0.6-1.4 |

| Omeprazole | 30-40 | 0.5-3.5 | 0.7 | 95 | 0.5-1 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 400-620 | 0.5-1.2 |

| Lansoprazole | 80-85 | 1.7 | 0.5-1.0 | 97 | 1.6 | 4.0 | 2.5 | 400-650 | 0.9-2.1 |

The PCABs reversibly block the potassium channel pump, inhibiting the gastric acid secretion and maintaining elevated intragastric pH for a long time[35]. Vonoprazan (a pyrrole derivative) and tegoprazan (a benzimidazole) are currently available PCABs in the market[8]. Vonoprazan fumarate is a food-independent, first-in-class PCAB. It is commonly used as an alternative to PPIs for H. pylori eradication[35]. Vonoprazan offers a novel mechanism of action with rapid, reversible, consistent, and potent acid suppression. This helps in improving symptom control and healing, particularly in refractory cases or those with nocturnal acid breakthrough[36]. Within two hours of administration, vonoprazan can reach maximum concentration in plasma, and its concentration is 108-fold higher in the secretory canaliculus of the parietal cell, compared to the plasma[37]. Mean half-life is 7.9 hours for vonoprazan and 1.4 hours for PPI lansoprazole, thus vonoprazan has significantly more potent inhibition of intragastric acidity (24-hour holding-time ratio for pH > 4) than PPI lansoprazole[38]. A tailored, patient-centric approach combining pharmacologic precision with behavioural modification optimizes long-term control of APDs[39]. Moreover, lifestyle interventions including dietary adjustments, weight management, sleep posture, and avoidance of known triggers (e.g., NSAIDs, alcohol, and smoking) remain integral to comprehensive care[40]. Inclusion of antioxidants, high fiber and protein in dietary plan, avoiding caffeine, fatty/spicy foods, milk, chewing gum, citrus fruits, or high intake of salt, and stress alleviation will help in maintaining the overall health of the patients[41].

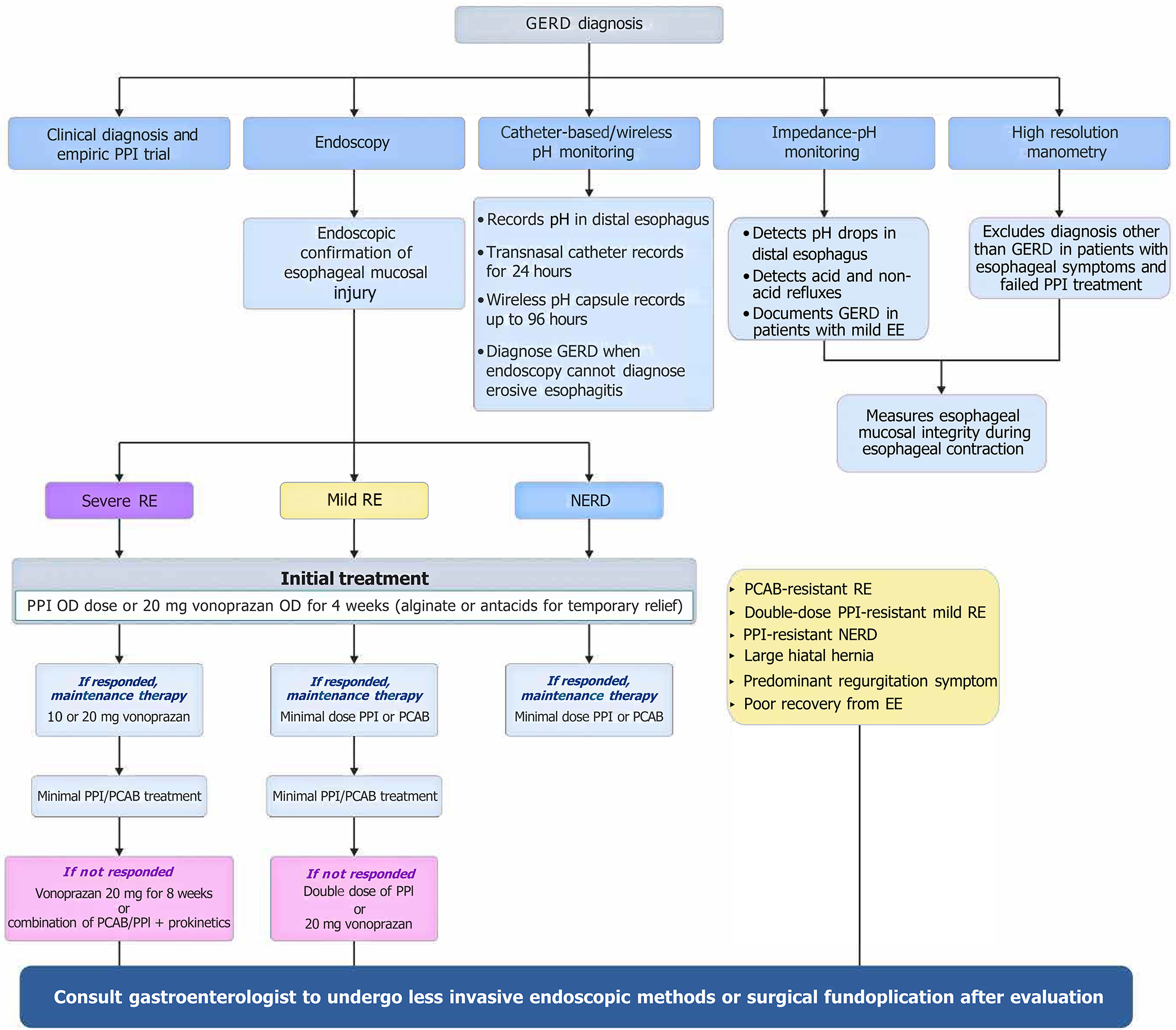

GERD is classified into erosive reflux disease (ERD), characterized by esophageal mucosal injuries, and non-ERD (NERD), having symptoms only, but no visible abnormalities[18]. The 2020 Indian Society of Gastroenterology and Association of Physicians of India consensus guidelines suggested a classical symptom (heartburn and sour regurgitation)-based diagnosis of GERD[16]. The 2022 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines recommended diagnostic endoscopy in patients whose classic GERD symptoms (recurrent reflux of stomach contents, heartburn, and/or regurgitation) are not responding to PPIs, only after stopping PPIs for at least 2 to 4 weeks[31]. No response or improvement in GERD symptoms following an 8-week PPI regimen is termed as refractory GERD[42]. The updated 2024 ACG guideline also suggested endoscopy as the initial evaluation in patients with dysphagia, other alarm symptoms like weight loss, GI bleeding, etc., or Barrett esophagus[43]. An algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of GERD[18,44] is provided in Figure 2.

Initial therapy of GERD: For patients with typical GERD without alarm symptoms, empiric therapy with once-daily PPIs before a meal for 4-8 weeks is recommended.

Statement 1: Once-daily oral PCAB administered independent of a meal can be an alternative to PPI. Level of agreement: A - 69.2%, B - 15.4%, C - 15.4%. A network meta-analysis supported full/standard doses of esomeprazole (40 mg/day for 4-8 weeks) as the first-line GERD therapy[45], while the 2024 Brazilian clinical guideline advised that over 8-week empirical PPI use should be limited to selected cases[46]. The PCABs, including vonoprazan, showed promising results in ERD, NERD, and PPI-resistant GERD[47]. Vonoprazan achieved 87.5% mucosal healing at 20 mg/day and 76.2% relapse prevention at 10 mg/day[48]. The panel recommended starting with once-daily PPIs for 4-8 weeks or PCABs for typical GERD without alarm features.

Statement 2: For the initial treatment of GERD, the efficacy of PCABs is comparable to that of PPIs. Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. The panel acknowledged that both PPIs and PCABs (e.g., vonoprazan) are effective and safe options for initial GERD therapy, as supported by the 2024 Brazilian clinical guidelines and other trials[46]. Vonoprazan demonstrated non-inferior efficacy to PPIs in treating erosive esophagitis and GERD[49,50], with a comparable safety profile confirmed across 14 clinical trials[51]. Additionally, vonoprazan therapy resulted in superior symptom relief and patient satisfaction in PPI-refractory GERD cases[52].

Statement 3: For patients with GERD who respond to 4-8 weeks of therapy, de-escalate the dose of PPI/PCAB or discontinue PPIs or PCABs. Level of agreement: A - 92.3%, B - 7.7%. The 2022 ACG guideline conditionally recommended attempting to discontinue PPIs in patients whose typical GERD symptoms improve following an 8-week empirical trial of PPI therapy[31]. The American Gastroenterological Association suggested dose tapering or abrupt discontinuation of PPIs, solely depending on the indication of PPI withdrawal[53]. The panel also discussed the factors that should be considered while de-escalating or discontinuing PPIs or PCABs in GERD patients. Patients having uncomplicated or NERD on a twice-daily PPI dose can be de-escalated to a once-daily dose, along with monitoring of the dose response. In case of good response, the maintenance dose can go down further to half of the once-daily dose and subsequently completely stopped unless symptoms return. The time for this weaning process may vary based on the physician’s discretion[54]. Tapering the PPI dose may help in successfully discontinuing the medication[55]. Implementation of a de-escalation protocol, provision of training and education for the providers as well as patients, could help in accomplishing discontinuation of PPIs and minimizing the rebound acid hypersecretion. The patients should be aware of the reappearing symptoms and prescribed H2RAs or antacids when required[56].

Statement 4: PCABs appear to be equally suitable for intermittent and on-demand use for acid suppression in the setting of GERD. Level of agreement: A - 38.5%, B - 61.5%. The 2022 Japanese Society of Gastroenterology (JSGE) guideline recommended a standard dose of PPI or PCAB (including on-demand therapy) as the initial therapy for mild reflux esophagitis[18]. The task force members discussed that PCABs are equally suitable for acid suppression when used intermittently or on demand. In patients with NERD, on-demand vonoprazan is a potential alternative to continued daily acid suppression therapy in relieving episodic heartburn[57]. A randomized trial reported that vonoprazan provided quick relief from heartburn symptoms of NERD[58]. Various doses of on-demand vonoprazan (10 mg, 20 mg, and 40 mg) have been proven to improve NERD symptoms within 3 hours of administration[59]. The therapeutic action of PCABs does not depend on a meal or require acidic pH, and the acid inhibition is irreversible, hence it is effective even when a dose is given in an intermittent manner[60]. Intermittent PCAB therapy is effective in healing esophagitis with additional benefits of cost-effectiveness because of fewer numbers of physician visits and required medication days[61].

Statement 5: The safety of PCABs during pregnancy has not been established. Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. Data for PCABs in pregnant and lactating populations are sparse[9]. The American Gastroenterological Association clinical practice update discussed that there are limited safety data for PCABs in pregnant and lactating populations. However, no toxicity of vonoprazan was observed in an animal study[62]. It is recommended to design more studies on the efficacy and safety of PCABs in pregnant women. Use of various acid suppressants in patients with renal/hepatic impairment is summarized in Table 3[19,21,63].

| Treatment | Indication | Dose/frequency | Risk/conditions |

| Renal impairment | |||

| Ranitidine[19] | GERD | 150 mg OD | Risk of toxic reactions: In elderly patients with reduced renal function, in patients with hepatic dysfunction |

| Famotidine[21] | Erosive esophagitis | 20 mg OD or 40 mg every other day | Risk of CNS adverse reactions and QT prolongation in moderate and severe renal impairment |

| GU/DU | |||

| Vonoprazan[63] | Erosive esophagitis | 10/20 mg OD | Not recommended: In severe renal impairment (eGFR < 30 mL/minute), for maintenance of healed erosive esophagitis |

| H. pylori eradication | 20 mg BD | ||

| Hepatic impairment | |||

| Vonoprazan[63] | Erosive esophagitis | 10/20 mg OD | Not recommended for H. pylori eradication in moderate to severe hepatic impairment |

| H. pylori eradication | 20 mg BD | ||

Choice of acid suppressant for recurrent and refractory symptoms: Statement 6: In patients with confirmed GERD, who do not respond to once-daily PPIs, options include twice-daily PPIs, dual-release PPIs, or PCABs. Level of agreement: A - 76.9%, B - 23.1%. While most GERD patients respond to once-daily PPI therapy, some require intensified treatment due to suboptimal response[64]. Many non-responders have functional esophageal disorders such as reflux hypersensitivity or functional heartburn[65]. Studies showed that twice-daily rabeprazole improved symptoms and quality of life more than once-daily dosing, with higher no-recurrence rates in moderate-to-severe erosive esophagitis cases[66,67]. Vonoprazan (20 mg) also achieved 87.5% mucosal healing in PPI-resistant cases, with 76.2% relapse prevention on maintenance[48]. Based on these findings, the panel recommended considering twice-daily PPIs, dual-release PPIs, or PCABs like vonoprazan for confirmed GERD unresponsive to standard PPI therapy.

Statement 7: Patients who do not respond to 4-8 weeks of empiric PPI or PCAB therapy require further investigations and evaluation. Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. The task force recommended further investigation and evaluation in patients not responding to 4-8 weeks of empiric PPI or PCAB therapy. The 2022 ACG guideline strongly recommended performing a diagnostic endoscopy, preferably after withholding PPIs for 2 to 4 weeks, in patients with typical GERD symptoms who fail to respond to an 8-week empiric trial of PPIs or whose symptoms recur upon discontinuation of therapy[31].

Statement 8: For symptomatic treatment of nocturnal acid breakthrough, the use of H2RA at bedtime, in addition to a PPI, is beneficial; alternative treatment options can be twice-daily PPIs, dual-release PPIs, or PCABs. Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. Addition of an H2RA to PPI demonstrated improvement in overall symptoms (72%), night-time reflux symptoms (74%), and GERD-associated sleep disturbance (67%)[68]. The same findings of a decrease in the prevalence rate of nocturnal gastric acid with the addition of an H2RA to PPI have been suggested by a Cochrane review[69]. Combination therapy of bedtime H2RA and PPI is superior to twice-daily PPI in controlling gastric acid secretion and nocturnal acid breakthrough[70]. However, H2RA efficacy may diminish over time due to tachyphylaxis[29], necessitating alternative strategies like PCABs for persistent symptoms. Vonoprazan has greater effectiveness in nighttime acid suppression than esomeprazole, even when compared to tegoprazan[71]. Based on the available evidence and experience of routine practice, the task force members recommended the addition of a bedtime H2RA to PPI for symptomatic treatment of nocturnal acid breakthrough. Additionally, twice-daily PPIs, dual-release PPIs, or PCABs/could be considered.

Acid suppression as maintenance therapy in severe or recurrent GERD: Statement 9: In patients with severe erosive esophagitis on endoscopy (Los Angeles grade C and D), PCABs are preferred over PPI for healing of esophagitis and symptom relief. Such patients require long-term maintenance therapy with PPIs or PCABs. Level of agreement: A - 92.3%, B - 7.7%. Recent meta-analyses confirmed vonoprazan as an effective and safe alternative to PPIs, especially in PPI-refractory GERD[72,73]. Vonoprazan offers faster acid suppression and superior healing of Los Angeles grade C/D erosive esophagitis, compared to PPIs[74,75]. Vonoprazan 20 mg once-daily showed significantly lower treatment failure rates than lansoprazole or omeprazole[75]. Based on the evidence, the panel recommended PCABs as the preferred option for patients with severe erosive esophagitis (Los Angeles grade C/D) for effective healing and symptom control.

Acid suppression in GERD-related complications - peptic stricture and Barrett’s esophagus: Statement 10: In complicated GERD (e.g., Barrett’s esophagus, esophageal peptic stricture), long-term acid suppression therapy with PPIs or PCABs is recommended. Level of agreement: A - 76.9%, B - 7.7%, C - 15.4%. Patients with complicated GERD, such as severe esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, or peptic strictures, typically require uninterrupted, long-term PPI therapy for mucosal healing and prevention of progression[31,76]. High-dose esomeprazole showed superior efficacy over pantoprazole in Barrett’s esophagus[77], though evidence on PPIs’ role in preventing progression to dysplasia or cancer remains mixed[78]. Variability in epithelial regeneration across PPIs has been observed[79]. The panel also acknowledged vonoprazan’s potential role and recommended long-term acid suppression with PPIs or PCABs in patients with complicated GERD.

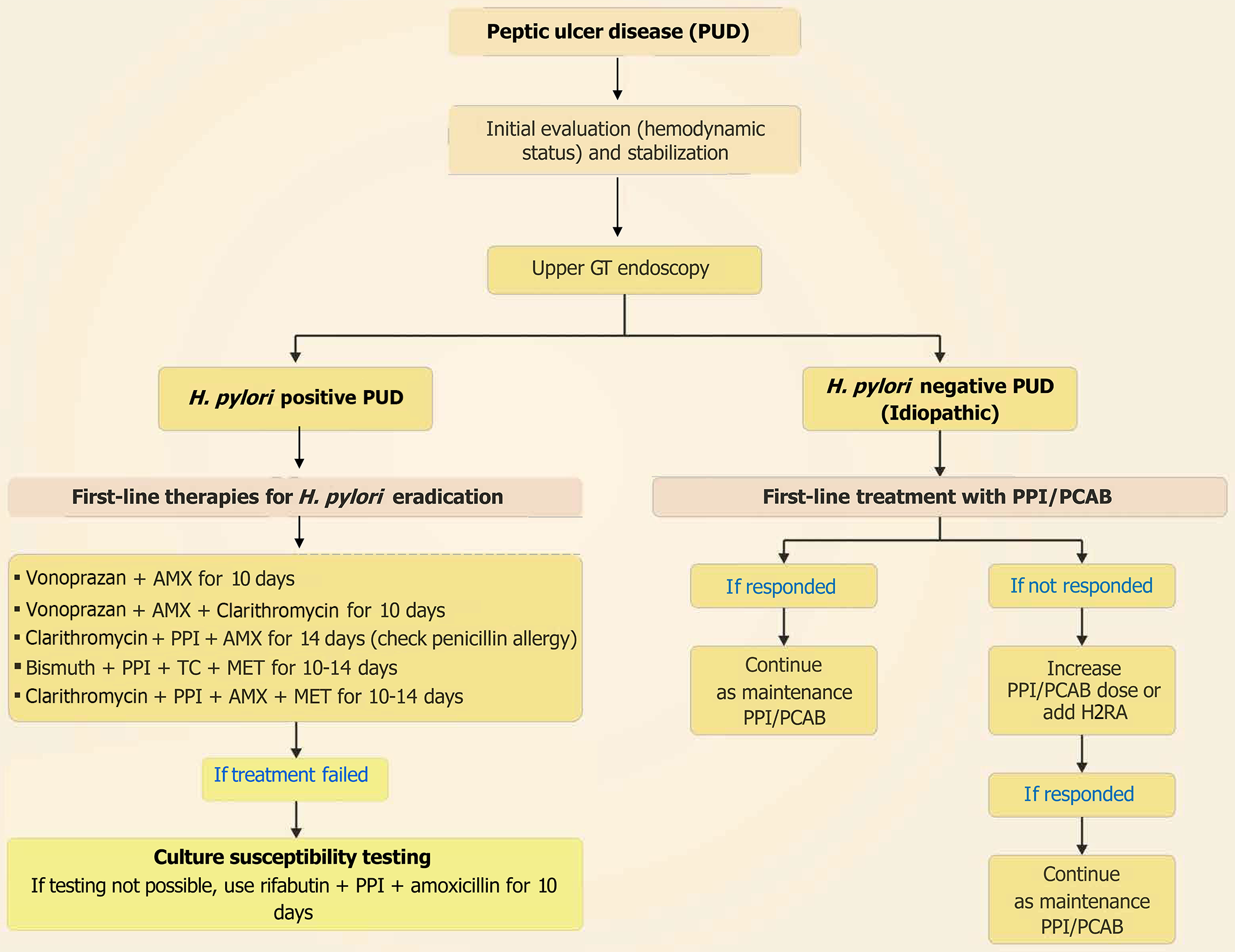

PUD commonly occurs in the stomach (gastric ulcer) or duodenum (duodenal ulcer) and is caused by H. pylori infection or the use of NSAIDs. It may progress to complicated PUD, characterized by acute GI bleeding, if left untreated[80]. Signs and symptoms of PUD include epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting (possibly with blood), anorexia or increased hunger, weight loss, melena, or dyspnea[81]. Uncomplicated PUD, defined as mucosal breaks without bleeding, perforation, or obstruction on endoscopy, may cause anemia without overt bleeding. Timely diagnosis and management are crucial to prevent complications[82]. For ulcers not linked to NSAID use or with active bleeding, infection testing for H pylori is advised[83]. The 2015 European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline recommended immediate assessment of the hemodynamic status of patients presenting with acute upper GI bleeding due to PUD[84]; while the 2021 ACG clinical guideline suggested endoscopy within 24 hours[85]. The 2020 World Society of Emergency Surgery guidelines recommended routine laboratory testing and arterial blood gas analysis for suspected gastroduodenal perforation, a computed tomography scan imaging or chest/abdominal X-ray if computed tomography scan imaging is not available for acute abdomen from suspected perforated peptic ulcer, and imaging with addition of water-soluble contrast (orally/via nasogastric tube) for acute abdomen from suspected perforated peptic ulcer, when free air is not visible in the imaging[86]. Diagnosis and treatment for PUD[30,87-89] are presented in Figure 3.

Choice of acid suppressant in uncomplicated duodenal ulcers and gastric ulcers: Statement 11: For the initial treatment of uncomplicated gastric and duodenal ulcers, oral PPIs or PCABs are recommended for 8-12 weeks. Level of agreement: A - 76.9%, B - 23.1%. The 2020 JSGE guideline recommended PPIs for the treatment of NSAID-induced ulcers in cases where NSAIDs cannot be discontinued[30]. The Japanese national health insurance system only permits use of PPI esomeprazole (20 mg once-daily) for 8 weeks for managing gastric ulcer and 6 weeks for duodenal ulcer[90]. A clinical practice guideline on PPI recommended short-term (2-12 weeks) PPI for peptic ulcer; after that, PPI therapy can be discontinued only if maintenance therapy is not indicated[22]. Vonoprazan could be used over PPIs for concomitant therapy in patients with a high risk of NSAID-induced peptic ulcers[7], or as an alternative to PPI because of its similar tolerability profile in gastric and duodenal ulcer healing, when used for 8 weeks[80]. On the basis of available evidence, the task force members recommended the use of oral PPI or PCABs/vonoprazan for 8-12 weeks in controlling uncomplicated gastric and duodenal ulcers. They further recommended consulting a gastroenterologist in case no optimum response is noticed after 8-12 weeks of PPI or PCABs use.

Statement 12: Patients with a history of PUD receiving long-term NSAIDs or aspirin should undergo evaluation and treatment for H. pylori infection to prevent recurrence of peptic ulcer and complications. Level of agreement: A - 100%, B - 0%. Guidelines suggested testing and eradication therapy for H. pylori to minimize the risk of recurrence and complications in patients with a prior history of PUD, who require long-term NSAIDs[91] or low-dose aspirin[30]. A prospective, randomized controlled trial reported that H. pylori eradication also lowers the recurrence rate of ulcer bleeding in aspirin users[92]. H. pylori eradication significantly reduces ulcer incidence, particularly in NSAID-naïve individuals[93]. However, in patients continuing NSAID therapy, H. pylori eradication alone may not suffice, and additional acid suppression with PPIs might be required[94,95]. Noninvasive evaluation of H. pylori infection through the urea breath test and stool antigen test offers precision in monitoring treatment outcomes without the use of recurrent invasive procedures[96]. The task force group suggested that patients with a history of PUD and receiving long-term NSAIDs or aspirin should undergo evaluation and treatment for H. pylori infection to prevent recurrence and complications. The members also recommended co-administering PPI or PCAB in case NSAIDs cannot be discontinued. The opinion is guideline-supported[30,91].

Choice of acid suppressant in refractory and recurrent PUD: Statement 13: If NSAIDs cannot be discontinued in patients with a history of PUD, co-administration of PPIs or PCABs is recommended for the prevention of ulcer recurrence and complications. Level of agreement: A - 61.5%, B - 38.5%. Long-term NSAIDs, low-dose aspirin, and H. pylori infection are the key risk factors for peptic ulcer bleeding[97]. The panel emphasized evaluating and treating H. pylori in patients on chronic NSAID or aspirin therapy, especially those with prior PUD. Co-administration of acid suppressants, particularly PPIs, is recommended to reduce ulcer recurrence and bleeding risk. A clinical practice guideline from Korea recommended the use of low-dose PPIs for reducing peptic ulcer and its complications in high-risk patients who are taking long-term NSAIDs. Guidelines from Korea and the 2021 JSGE supported low-dose PPIs in high-risk patients on long-term NSAIDs or low-dose aspirin[30,91]. The panel also supported PCABs as effective alternatives to PPIs, with studies showing similar efficacy and safety in preventing NSAID-induced ulcer recurrence[98,99].

Statement 14: In patients at high risk for peptic ulcers, PCABs are equally or more effective than PPIs in preventing ulcer recurrence. Level of agreement: A - 46.2%, B - 53.8%. The panel discussed whether PCABs are equally or more effective than PPIs in preventing ulcer recurrence in patients at high risk for peptic ulcers with reference to current evidence. A systematic review indicated that PCABs are non-inferior to PPIs in preventing ulcer recurrence during NSAID therapy, with comparable safety outcomes[100]. Vonoprazan, a PCAB, prevents drug-induced ulcers and offers faster symptom relief in acid-related disorders[101-103]. Vonoprazan has shown similar effectiveness and long-term safety profile in preventing NSAID-related peptic ulcer recurrence as lansoprazole in at-risk patients[99]. Vonoprazan demonstrated better ulcer healing rates and H. pylori eradication, particularly in H. pylori-positive cases, suggesting its advantage over PPIs in certain clinical contexts[104]. More head-to-head comparisons reflecting the efficacy and safety of PPIs and PCABs in preventing ulcer recurrence are required to guide clinical decision-making and provide better treatment options.

Statement 15: For refractory peptic ulcers persisting after 8-12 weeks of standard anti-secretory therapy and H. pylori eradication, the PPI dose can be doubled, or an alternative PCAB may be considered. Level of agreement: A - 69.2%, B - 30.8%. Despite using standard anti-secretory drug treatment, refractory (for 8 to 12 weeks) peptic ulcers exist, probably due to NSAID use, persistent H. pylori infections, or resistant strains[105]. A 36-week course of oral esomeprazole (20 mg, once- or twice-daily) decreased bleeding from refractory or recurrent ulcer (size ≥ 0.5 cm); however, this needed to be validated when PPIs are no longer continued[106]. In cases where peptic ulcers do not heal despite an adequate course of standard PPI therapy, modifying the treatment approach may be necessary. The panel recommended doubling the PPI dose or an alternative PPI/PCAB therapy in refractory peptic ulcers existing even after 8-12 weeks of standard anti-secretory therapy and H. pylori eradication or a full course of PPI therapy. Evidence from 2009 Korean diagnostic guidelines suggested doubling and extending (additional 6-8 weeks) PPI therapy if ulcer healing is not achieved after 8-12 weeks of standard-dose anti-secretory treatment[105,107].

Acid suppression in bleeding peptic ulcers: Statement 16: In patients with upper GI bleeding, pre-endoscopy intravenous (IV) PPI administration is recommended, especially if early endoscopy or endoscopic expertise is unavailable within 24 hours. Level of agreement: A - 69.2%, B - 30.8%. The 2021 ESGE guideline recommended performing upper GI endoscopy within 24 hours after hemodynamic stabilization, but not urgently within 12 hours[108]. For patients with high-risk stigmata, high-dose IV PPI with a loading dose followed by 72-hour infusion is advised post-endoscopy[109]. Cochrane reviews showed that pre-endoscopy PPI may reduce the need for endoscopic intervention, though its impact on outcomes like mortality or rebleeding is unclear[110,111]. The 2021 ACG also stated initiating PPI at presentation and continuing high-dose therapy post-endoscopy to reduce rebleeding risk[85]. The evidence-based discussion led to the recommendation of administering IV PPI prior to endoscopy, especially when early endoscopy or expertise is unavailable within 24 hours.

Statement 17: Acid suppressive therapy as an adjunct to endoscopic management of bleeding peptic ulcers - during the initial 72 hours, a bolus dose followed by IV PPI infusion or twice-daily PPI or oral PCABs is recommended: (1) Level of agreement: A - 76.9%, B - 23.1%. The 2021 ESGE guideline recommended administering high-dose PPI therapy via IV bolus and continuous infusion (e.g., 80 mg IV bolus followed by 8 mg/hour infusion) for 72 hours in patients with bleeding PUD post-endoscopic hemostasis. Oral/IV bolus dosing twice daily may also be an effective alternative[108]. Oral vonoprazan is a non-inferior alternative to IV PPIs in preventing 30-day rebleeding after endoscopic hemostasis[102]. The 2021 ACG clinical guideline suggested continuous or intermittent high-dose PPI therapy for three days post-endoscopy, followed by twice-daily oral PPI for two weeks to maintain hemostasis and prevent recurrence; in cases of recurrent bleeding, repeat endoscopy or transcatheter embolization is advised[85]. The panel therefore recommended a bolus dose followed by IV PPI infusion, twice-daily PPI, or oral PCABs such as vonoprazan as an adjunct to endoscopic management of bleeding peptic ulcers during the initial 72 hours of bleeding peptic ulcers. High-dose oral PPI is a cost-effective and non-inferior alternative in selected populations; (2) Level of agreement: A - 61.5%, B - 38.5%. Intermittent IV, IV bolus, and oral PPI regimens demonstrated similar clinical effectiveness, suggesting that 72-hour continuous IV infusion may not always be necessary - even in high-risk cases[112]. Similar clinical outcomes between high-dose oral and IV PPIs were observed for preventing rebleeding in high-risk patients[113]. A systematic review and meta-analysis also reported similar efficacy of oral and IV PPIs in preventing rebleeding, reducing the need for surgery, and minimizing mortality across varying ulcer stigmata; oral PPIs also provide additional cost-saving benefits. In addition, patients receiving high-dose oral PPI therapy require fewer blood transfusions, compared to those receiving IV PPIs[114]. Therefore, the panel recommended high-dose oral PPI as a cost-effective and non-inferior alternative to IV PPI therapy when used as an adjunct to endoscopic management of bleeding peptic ulcers. After 72 hours of IV PPI, high-dose oral PPI is recommended for 2-4 weeks to prevent rebleeding or surgery. PCABs may serve as an alternative to high-dose PPIs; and (3) Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. The international consensus group guideline, based on expert opinion, suggested that following the initial 72-hour course of high-dose IV PPI therapy, high-risk patients with bleeding peptic ulcers should continue with oral high-dose PPI therapy, preferably twice daily for the first 14 days. This would effectively maintain acid suppression and lower the chances of rebleeding or surgical intervention[109]. Similarly, the 2021 ACG guideline advised either continuous or intermittent high-dose IV PPI for the initial 3 days after endoscopic hemostasis, followed by twice-daily oral PPI for 2 weeks[85]. Cheng and Sheu[115] reported that extending IV PPI therapy (lower doses) up to 7 days may provide better control of recurrent bleeding episodes in patients with co

Statement 18: For H. pylori eradication, PCAB-based regimens (dual, triple, or bismuth quadruple therapy) are preferred over PPI-based regimens. Standard vonoprazan dosing: 20 mg twice-daily for 10-14 days. Level of agreement: A - 84.6%, B - 15.4%. Vonoprazan-based dual (with amoxicillin) and triple (with amoxicillin and clarithromycin) therapy were reported to be superior to lansoprazole for H. pylori eradication[116]. Vonoprazan-based triple therapy outperformed PPI-based triple therapy with a significant improvement in H. pylori eradication rates[117]. Two-week vonoprazan-based triple therapy outperforms all other regimens, including PPI-based quadruple therapies in terms of eradication rate[118]. Vonoprazan-based quadruple therapy for 10 days or 14 days offers the highest efficacy in H. pylori eradication and is especially recommended in regions with high antibiotic resistance[119]. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis comparing PCABs and PPIs in 8818 patients found that PCAB-based regimens, particularly vonoprazan, showed significantly higher H. pylori eradication rates than PPI-based regimens[120]. Consistent with the literature findings, the panel recommended vonoprazan-based regimens (dual, triple, or bismuth quadruple therapy) over PPI-based regimens for H. pylori eradication. Standard vonoprazan dosing of 20 mg twice-daily for 10-14 days is recommended.

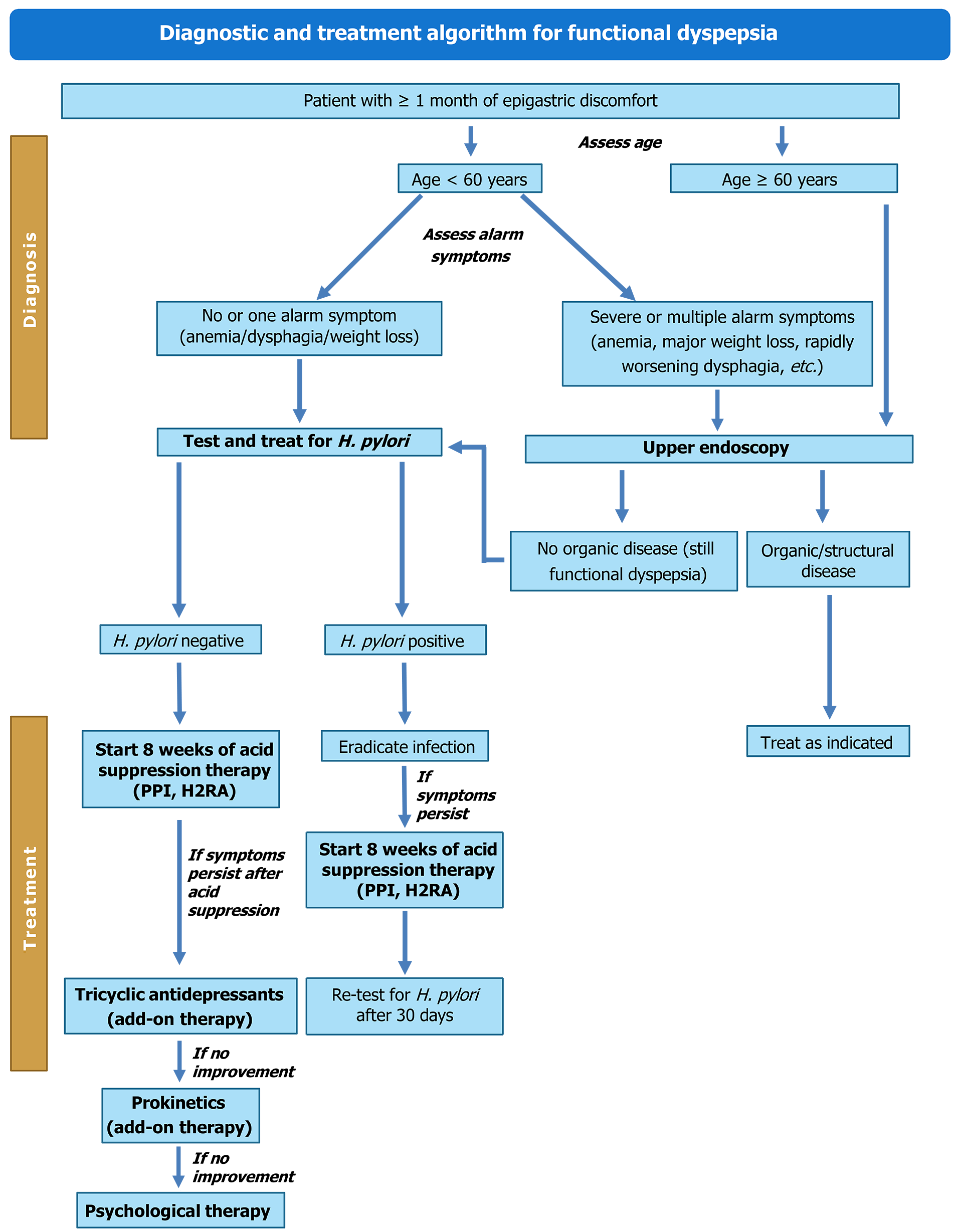

Active symptoms like bothersome epigastric pain/burning, early satiation, and/or postprandial fullness for three months as per the Rome IV criteria indicate the presence of FD[121]. A full blood count in patients aged ≥ 55 years with dyspepsia, celiac serology in patients with FD and irritable bowel syndrome, and urgent endoscopy in the absence of upper GI alarm symptoms in patients (≥ 55 years) with dyspepsia and weight loss or in patients aged > 40 years with a family history of gastroesophageal cancer were recommended[121]. The panel pointed out that in patients aged > 60 years with dyspepsia symptoms for ≥ 1 month, endoscopy should be prioritized. However, in younger patients, H. pylori testing followed by eradication therapy, and if needed, endoscopy should be done. The suggested diagnosis and treatment algorithm for managing FD[121-123] is given in Figure 4.

Statement 19: In patients with symptoms suggestive of FD, acid suppressive therapy should only be offered after investigations and H. pylori testing and eradication. Level of agreement: A - 61.5%, B - 38.5%. H. pylori “test-and-treat” strategy is an increasingly accepted idea for diagnostic-therapeutic approach in patients with FD[124]. H. pylori testing and eradication have been suggested by the 2022 British Society of Gastroenterology guideline for H. pylori-positive patients with FD and empirical acid suppression therapy in patients without H. pylori infection. The guideline further recommended PPIs for their effectiveness and tolerance for the treatment of FD[121]. A PPI- or PCAB-based clarithromycin triple therapy is recommended by the 2024 ACG guideline for patients who remain H. pylori-positive after treatment and if the infection is clarithromycin-sensitive[125]. In patients with PPI-refractory FD, lower-dose vonoprazan (10 mg) showed significant improvement in FD symptoms and quality of life[126]. However, if FD symptoms are not decreased by acid suppressive therapy, then tricyclic antidepressants followed by prokinetics (itopride is preferred) and psychological therapy could be considered[122,123]. The panel recommended that acid suppressive therapy should only be offered after appropriate investigations and after H. pylori testing and eradication in patients with FD symptoms.

Statement 20: Acid suppression in FD can be achieved with H2RAs, PPIs, or PCABs. In patients not responding to PPI or H2RA therapy, PCABs are effective. Level of agreement: A - 46.2%, B - 53.8%. Both PPIs and H2RAs across various doses are more effective than placebo in improving FD symptoms, with standard-dose PPIs ranking highest in treatment efficacy[127]. The 2021 JSGE guideline has suggested the same[128]. Similarly, the 2022 British Society of Gastroenterology guideline affirms that lower-dose PPIs are effective in controlling FD symptoms due to the absence of a clear dose-response relationship. The H2RAs are reported to be well-tolerated and may be an effective option, although the quality of supporting evidence is low[121]. PCABs could be used as an initial therapy for FD, as well as in patients not responding to 8 weeks of conventional PPI therapy[129]. Vonoprazan significantly improved symptoms and quality of life in FD patients unresponsive to PPIs, suggesting that a 10 mg dose could be a viable alternative to PPI[126]. The panel recommended acid suppression in FD using H2RAs, PPIs, or PCABs, with a specific recommendation for PCABs when patients are unresponsive to PPI or H2RA therapy.

The panel proposed a comprehensive algorithm (Figure 5) to provide clear guidance for distinguishing the overlapping symptoms of two or more GI disorders. This will help in timely diagnosis and appropriate medical interventions, aiming to reduce morbidity and mortality and significantly improve the patient’s quality of life. The APD 360° compass, by integrating global and Indian clinical guidelines, will support clinicians in making informed, patient-centred decisions, thus enhancing treatment outcomes and helping to reduce the disease burden.

In summary, start with once-daily PPIs (or twice-daily/dual-release PPIs) or intermittent/on-demand PCABs (e.g., vonoprazan) for managing typical GERD, and perform therapy de-escalation/discontinuation with caution after personalized risk stratification. The same therapy or bedtime H2RA with PPI is recommended for nocturnal acid breakthrough. In severe erosive esophagitis or complicated GERD, the panel acknowledged vonoprazan’s effectiveness. A gastroenterologist can help in controlling an uncomplicated gastric and duodenal ulcer in case of failed treatment with PPI or PCAB/vonoprazan for 8-12 weeks. Additionally, evaluation and eradication of H. pylori are recommended for patients with a prior history of PUD, currently having NSAID or aspirin use. Vonoprazan 20 mg twice-daily for 10-14 days is recommended over PPI for H. pylori eradication. If PUD exists after 8-12 weeks of standard anti-secretory therapy and H. pylori eradication, or a full course of PPI therapy, doubling the PPI dose or an alternative PPI/PCAB therapy is recommended. In addition to endoscopic management of bleeding peptic ulcers, IV PPI (high-dose PPI is a cost-effective alternative), twice-daily PPI, or oral PCAB (vonoprazan) should be considered. Use of H2RA or PPI for patients with FD is recommended. The PCABs are suggested if the patient is non-responsive to the former therapy.

| 1. | Jankovic K, Gralnek IM, Awadie H. Emerging Long-Term Risks of the Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers. Annu Rev Med. 2025;76:143-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rai RR, Gangadhar A, Mayabhate MM. Clinical profiling of patients with Acid Peptic Disorders (APD) in India: a cross-sectional survey of clinicians. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;6:194. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Quach DT, Ha QV, Nguyen CT, Le QD, Nguyen DT, Vu NT, Dang NL, Le NQ. Overlap of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Functional Dyspepsia and Yield of Esophagogastroduodenoscopy in Patients Clinically Fulfilling the Rome IV Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:910929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sud R, Pebbili KK, Desai SA, Bhagat S, Rathod R, Mane A, Kotak B. Dyspepsia - The Indian perspective: A cross sectional study on demographics and treatment patterns of Dyspepsia from across India (Power 1.0 study). J Assoc Physicians India. 2023;71:11-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bai SK, Reddy R. A clinical study on peptic ulcer in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Med Res Prof. 2022;8:102-104. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Thapa R, Pokharel M, Paudel S, Khadka T, Sapkota P, Rana R, Pokharel M, Chhetri D. Acid Peptic Disease among Patients with Acute Abdomen Visiting the Department of Emergency Medicine in a Tertiary Care Centre. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2023;61:636-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Upadhyay R, Soni NK, Vora A, Saraf A, Haldipur D, Mukherjee D, Das D, Tiwaskar M, Nadkar M, Arun N, Kumar RB, Bhadade R, Rai RR, Bhargava S, Parikh S, Shetty S, Kant S, Jalihal U, Prasad VGM, Kotamkar A, Pallewar S, Qamra A. Association of Physicians of India Consensus Recommendations for Vonoprazan in Management of Acid Peptic Disorders. J Assoc Physicians India. 2025;73:68-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al-Frejat Z, Martini N, Esper A, Al-Frejat D, Younes S, Hanna M. GERD: Latest update on acid-suppressant drugs. Curr Res Pharmacol Drug Discov. 2024;7:100198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wong N, Reddy A, Patel A. Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers: Present and Potential Utility in the Armamentarium for Acid Peptic Disorders. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2022;18:693-700. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Aggarwal R. Indian Journal of Gastroenterology –July–August 2023—highlights. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42:443-447. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Geeraerts A, Van Houtte B, Clevers E, Geysen H, Vanuytsel T, Tack J, Pauwels A. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease-Functional Dyspepsia Overlap: Do Birds of a Feather Flock Together? Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:1167-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johnson DA, Katz PO, Armstrong D, Cohen H, Delaney BC, Howden CW, Katelaris P, Tutuian RI, Castell DO. The Safety of Appropriate Use of Over-the-Counter Proton Pump Inhibitors: An Evidence-Based Review and Delphi Consensus. Drugs. 2017;77:547-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | M ZA, Lavu A, Ansari M, V RA, Vilakkathala R. A Cross-Sectional Study on Single-Day Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors in Tertiary Care Hospitals of South India. Hosp Pharm. 2021;56:109-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chasta P, Ahmad A. Reviewing The Peptic Ulcers in Immunocompromised Patients: Challenges and Management Strategies. Int J Pharm Sci. 2025;3:2915-2927. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Ghosh S, Hiwale KM. Challenges in Diagnosis and Management of Unusual Cases of Eosinophilic Enteritis in Rural Health Settings: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2024;16:e55398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Bhatia S, Pareek KK, Kumar A, Upadhyay R, Tiwaskar M, Jain A, Gupta P, Nadkar MY, Prakash A, Dutta A, Chavan R, Kedia S, Ahuja V, Ghoshal U, Agarwal A, Makharia G. API-ISG Consensus Guidelines for Management of Gastrooesophageal Reflux Disease. J Assoc Physicians India. 2020;68:69-80. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yadlapati R, Gyawali CP, Pandolfino JE; CGIT GERD Consensus Conference Participants. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Personalized Approach to the Evaluation and Management of GERD: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:984-994.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Iwakiri K, Fujiwara Y, Manabe N, Ihara E, Kuribayashi S, Akiyama J, Kondo T, Yamashita H, Ishimura N, Kitasako Y, Iijima K, Koike T, Omura N, Nomura T, Kawamura O, Ohara S, Ozawa S, Kinoshita Y, Mochida S, Enomoto N, Shimosegawa T, Koike K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for gastroesophageal reflux disease 2021. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:267-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | ZANTAC®. SmPC: Ranitidine Hydrochloride. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2009/018703s068,019675s035,020251s019lbl.pdf. |

| 20. | NEXIUM. SmPC: Esomeprazole Magnesium. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/022101s014021957s017021153s050lbl.pdf. |

| 21. | PEPCID®. SmPC: Famotidine. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/019462s039lbl.pdf. |

| 22. | Farrell B, Pottie K, Thompson W, Boghossian T, Pizzola L, Rashid FJ, Rojas-Fernandez C, Walsh K, Welch V, Moayyedi P. Deprescribing proton pump inhibitors: Evidence-based clinical practice guideline. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:354-364. [PubMed] |

| 23. | PROTONIX. SmPC: Pantoprazole Sodium. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/022020s011-020987s049lbl.pdf. |

| 24. | DEXILANT. SmPC: Dexlansoprazole. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/022287s014lbl.pdf. |

| 25. | Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. Government of India: List of New Drugs Approved 2011. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://cdsco.gov.in/opencms/resources/UploadCDSCOWeb/2018/UploadApprovalNewDrugs/approvalsnd211.pdf. |

| 26. | ACIPHEX®. SmPC: Rabeprazole Sodium. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2014/020973s035204736s005lbl.pdf. |

| 27. | PRILOSEC. SmPC: Omeprazole. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2012/019810s096lbl.pdf. |

| 28. | Central Drugs Standard Control Organization. Government of India: New Drugs Approved by CDSCO. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://cdscoonline.gov.in/CDSCO/Drugs. |

| 29. | Hunt R, Armstrong D, Katelaris P, Afihene M, Bane A, Bhatia S, Chen MH, Choi MG, Melo AC, Fock KM, Ford A, Hongo M, Khan A, Lazebnik L, Lindberg G, Lizarzabal M, Myint T, Moraes-Filho JP, Salis G, Lin JT, Vaidya R, Abdo A, LeMair A; Review Team:. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guidelines: GERD Global Perspective on Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:467-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kamada T, Satoh K, Itoh T, Ito M, Iwamoto J, Okimoto T, Kanno T, Sugimoto M, Chiba T, Nomura S, Mieda M, Hiraishi H, Yoshino J, Takagi A, Watanabe S, Koike K. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2020. J Gastroenterol. 2021;56:303-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 31.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Katz PO, Dunbar KB, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Greer KB, Yadlapati R, Spechler SJ. ACG Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:27-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 748] [Cited by in RCA: 580] [Article Influence: 145.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 32. | Shin JM, Kim N. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the proton pump inhibitors. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;19:25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Song H, Zhu J, Lu D. Long-term proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use and the development of gastric pre-malignant lesions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD010623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Strand DS, Kim D, Peura DA. 25 Years of Proton Pump Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review. Gut Liver. 2017;11:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Herszényi L, Bakucz T, Barabás L, Tulassay Z. Pharmacological Approach to Gastric Acid Suppression: Past, Present, and Future. Dig Dis. 2020;38:104-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Abraham P, Choudhuri G, Deshmukh S, Kak M, Tiwaskar M, Kochhar R, Sinha SK, Panigrahi SC, Shandil R, Khanna M, Garg R, Lamba GS, Jain M, Poddar P, Mishra A, Shah A, Kantharia C, Shah H, Saha I, Vazifdar K, Jain L, Borse N, Garg P, Kumar M, Sahu M, Nath P, Singh R, Sahu V, Bandyopadhyay S, Jaiswal S, Patil D, Bodas S, Vaghasia S, Khanna S, Swami OC, Chakravarty S, Murthy KV, Kumar V. Vonoprazan in Management of Refractory Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: An Indian Expert Group Consensus Statements. J Assoc Physicians India. 2025;73:e29-e36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Oshima T, Miwa H. Potent Potassium-competitive Acid Blockers: A New Era for the Treatment of Acid-related Diseases. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:334-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Laine L, Sharma P, Mulford DJ, Hunt B, Leifke E, Smith N, Howden CW. Pharmacodynamics and Pharmacokinetics of the Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker Vonoprazan and the Proton Pump Inhibitor Lansoprazole in US Subjects. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117:1158-1161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Heidelbaugh JJ. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of vitamin and mineral deficiency: evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2013;4:125-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ness-Jensen E, Hveem K, El-Serag H, Lagergren J. Lifestyle Intervention in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:175-82.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kulshreshtha M, Srivastava G, Singh M. Pathophysiological status and nutritional therapy of peptic ulcer: An update. Environ Dis. 2017;2:76-86. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Verma S, Padmanabhan P, Sundar B, Dinakaran N. Refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): A clinical, endoscopic, and histopathological perspective –a single centre cross-sectional study. Gastroenterol Endosc. 2024;2:107-111. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 43. | Patti MG, BS Anand. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Treatment & Management. Drugs & Diseases 2024. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176595-treatment?form=fpf. |

| 44. | Liang SW, Wong MW, Yi CH, Liu TT, Lei WY, Hung JS, Lin L, Rogers BD, Chen CL. Current advances in the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Tzu Chi Med J. 2022;34:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhang H, Yang Z, Ni Z, Shi Y. A Meta-Analysis and Systematic Review of the Efficacy of Twice Daily PPIs versus Once Daily for Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:9865963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Moraes-Filho JPP, Domingues G, Chinzon D; Brazilian GERD Counselors. Brazilian Clinical Guideline for The Therapeutic Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (Brazilian Federation of Gastroenterology, FBG). Arq Gastroenterol. 2024;61:e23154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Seo S, Jung HK, Gyawali CP, Lee HA, Lim HS, Jeong ES, Kim SE, Moon CM. Treatment Response With Potassium-competitive Acid Blockers Based on Clinical Phenotypes of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Literature Review and Meta-analysis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2024;30:259-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Hoshino S, Kawami N, Takenouchi N, Umezawa M, Hanada Y, Hoshikawa Y, Kawagoe T, Sano H, Hoshihara Y, Nomura T, Iwakiri K. Efficacy of Vonoprazan for Proton Pump Inhibitor-Resistant Reflux Esophagitis. Digestion. 2017;95:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Cheng Y, Liu J, Tan X, Dai Y, Xie C, Li X, Lu Q, Kou F, Jiang H, Li J. Direct Comparison of the Efficacy and Safety of Vonoprazan Versus Proton-Pump Inhibitors for Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Simadibrata DM, Syam AF, Lee YY. A comparison of efficacy and safety of potassium-competitive acid blocker and proton pump inhibitor in gastric acid-related diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37:2217-2228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Howden CW, Katz P, DeVault KR, Metz DC, Tamene D, Smith N, Hunt B, Chang YM, Spechler SJ. Integrated Analysis of Vonoprazan Safety for Symptomatic Gastro-Oesophageal Reflux Disease or Erosive Oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2025;61:835-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Gotoh Y, Ishibashi E, Honda S, Nakaya T, Noguchi C, Kagawa K, Murakami K. Efficacy of vonoprazan for initial and maintenance therapy in reflux esophagitis, nonerosive esophagitis, and proton pump inhibitor-resistant gastroesophageal reflux disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e19520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Targownik LE, Fisher DA, Saini SD. AGA Clinical Practice Update on De-Prescribing of Proton Pump Inhibitors: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1334-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 45.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Pandolfino J. Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitor therapy and the role of esophageal testing. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:747-764. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Björnsson E, Abrahamsson H, Simrén M, Mattsson N, Jensen C, Agerforz P, Kilander A. Discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors in patients on long-term therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:945-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Swiger C, Hoang M, Wagner E, Zents M. The Adverse Effects of Proton Pump Inhibitors and How to De-Escalate Therapy. Transform Med. 2023;2:75-78. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 57. | Fass R, Vaezi M, Sharma P, Yadlapati R, Hunt B, Harris T, Smith N, Leifke E, Armstrong D. Randomised clinical trial: Efficacy and safety of on-demand vonoprazan versus placebo for non-erosive reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2023;58:1016-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Laine L, Spechler S, Yadlapati R, Schnoll-Sussman F, Smith N, Leifke E, Harris T, Hunt B, Fass R, Katz P. Vonoprazan is Efficacious for Treatment of Heartburn in Non-erosive Reflux Disease: A Randomized Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024;22:2211-2220.e10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Vélez C. On-Demand Vonoprazan for Non-Erosive Reflux Disease Symptoms: A New Option. Nov 19, 2024. [cited 3 August 2025]. Available from: https://gi.org/journals-publications/ebgi/velez_nov2024/. |

| 60. | Mazumder A, Kumar N, Das S. Medical Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and the Challenges: A Review. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2022;12:902-909. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 61. | Habu Y, Hamasaki R, Maruo M, Nakagawa T, Aono Y, Hachimine D. Treatment strategies for reflux esophagitis including a potassium-competitive acid blocker: A cost-effectiveness analysis in Japan. J Gen Fam Med. 2021;22:237-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Patel A, Laine L, Moayyedi P, Wu J. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Integrating Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers Into Clinical Practice: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2024;167:1228-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | VOQUEZNA®. SmPC: Vonoprazan. [cited 17 March 2025]. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2023/215151s000lbl.pdf. |

| 64. | Katz PO, Zavala S. Proton pump inhibitors in the management of GERD. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14 Suppl 1:S62-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Abdallah J, George N, Yamasaki T, Ganocy S, Fass R. Most Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease Who Failed Proton Pump Inhibitor Therapy Also Have Functional Esophageal Disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1073-1080.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Kinoshita Y, Hongo M, Kusano M, Furuhata Y, Miyagishi H, Ikeuchi S; RPZ Study Group. Therapeutic Response to Twice-daily Rabeprazole on Health-related Quality of Life and Symptoms in Patients with Refractory Reflux Esophagitis: A Multicenter Observational Study. Intern Med. 2017;56:1131-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Kinoshita Y, Kato M, Fujishiro M, Masuyama H, Nakata R, Abe H, Kumagai S, Fukushima Y, Okubo Y, Hojo S, Kusano M. Efficacy and safety of twice-daily rabeprazole maintenance therapy for patients with reflux esophagitis refractory to standard once-daily proton pump inhibitor: the Japan-based EXTEND study. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:834-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Rackoff A, Agrawal A, Hila A, Mainie I, Tutuian R, Castell DO. Histamine-2 receptor antagonists at night improve gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms for patients on proton pump inhibitor therapy. Dis Esophagus. 2005;18:370-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Wang Y, Pan T, Wang Q, Guo Z. Additional bedtime H2-receptor antagonist for the control of nocturnal gastric acid breakthrough. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2009:CD004275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Mainie I, Tutuian R, Castell DO. Addition of a H2 receptor antagonist to PPI improves acid control and decreases nocturnal acid breakthrough. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:676-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Yang E, Kim S, Kim B, Kim B, Kim Y, Park SS, Song GS, Yu KS, Jang IJ, Lee S. Night-time gastric acid suppression by tegoprazan compared to vonoprazan or esomeprazole. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2022;88:3288-3296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Agago DE, Hanif N, Ajay Kumar AS, Arsalan M, Kaur Dhanjal M, Hanif L, Wei CR. Comparison of Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers and Proton Pump Inhibitors in Patients With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Cureus. 2024;16:e65141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Narendra IBP. Comparing Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker And Proton Pump Inhibitor For Gastroeshopageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review And Meta-Analysis. Jurnal Inovasi Global. 2025;3:577-589. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 74. | Xiao Y, Zhang S, Dai N, Fei G, Goh KL, Chun HJ, Sheu BS, Chong CF, Funao N, Zhou W, Chen M. Phase III, randomised, double-blind, multicentre study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of vonoprazan compared with lansoprazole in Asian patients with erosive oesophagitis. Gut. 2020;69:224-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Zhuang Q, Chen S, Zhou X, Jia X, Zhang M, Tan N, Chen F, Zhang Z, Hu J, Xiao Y. Comparative Efficacy of P-CAB vs Proton Pump Inhibitors for Grade C/D Esophagitis: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2024;119:803-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Kecskemeti KL, Borgaonkar M, McGrath J. Assessing Frequency and Appropriateness of Proton Pump Inhibitor Deprescription in Patients Requiring Endoscopic Therapy for Esophageal Strictures. J Can Assoc Gastroenterol. 2023;6:229-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | de Bortoli N, Martinucci I, Piaggi P, Maltinti S, Bianchi G, Ciancia E, Gambaccini D, Lenzi F, Costa F, Leonardi G, Ricchiuti A, Mumolo MG, Bellini M, Blandizzi C, Marchi S. Randomised clinical trial: twice daily esomeprazole 40 mg vs. pantoprazole 40 mg in Barrett's oesophagus for 1 year. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1019-1027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Li L, Cao Z, Zhang C, Pan W. Risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett's esophagus using proton pump inhibitors: a systematic review with meta-analysis and sequential trial analysis. Transl Cancer Res. 2021;10:1620-1627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Babic Z, Bogdanovic Z, Dorosulic Z, Petrovic Z, Kujundzic M, Banic M, Marusic M, Heinzl R, Bilić B, Andabak M. One year treatment of Barrett's oesophagus with proton pump inhibitors (a multi-center study). Acta Clin Belg. 2015;70:408-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Miwa H, Uedo N, Watari J, Mori Y, Sakurai Y, Takanami Y, Nishimura A, Tatsumi T, Sakaki N. Randomised clinical trial: efficacy and safety of vonoprazan vs. lansoprazole in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcers - results from two phase 3, non-inferiority randomised controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:240-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 81. | Tilva T, Dholakiya A. A Review on Peptic Ulcer Disease: Diagnosis and Management Approach. Int J Creative Res Thoughts. 2023;11:d158-d176. |

| 82. | Ruigómez A, Johansson S, Nagy P, Martín-Pérez M, Rodríguez LA. Risk of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease in a cohort of new users of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014;14:205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Satoh K, Yoshino J, Akamatsu T, Itoh T, Kato M, Kamada T, Takagi A, Chiba T, Nomura S, Mizokami Y, Murakami K, Sakamoto C, Hiraishi H, Ichinose M, Uemura N, Goto H, Joh T, Miwa H, Sugano K, Shimosegawa T. Evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for peptic ulcer disease 2015. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:177-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ, Lanas A, Sanders DS, Kurien M, Rotondano G, Hucl T, Dinis-Ribeiro M, Marmo R, Racz I, Arezzo A, Hoffmann RT, Lesur G, de Franchis R, Aabakken L, Veitch A, Radaelli F, Salgueiro P, Cardoso R, Maia L, Zullo A, Cipolletta L, Hassan C. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 472] [Cited by in RCA: 519] [Article Influence: 47.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Laine L, Barkun AN, Saltzman JR, Martel M, Leontiadis GI. ACG Clinical Guideline: Upper Gastrointestinal and Ulcer Bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2021;116:899-917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 86. | Tarasconi A, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, Tomasoni M, Ansaloni L, Picetti E, Molfino S, Shelat V, Cimbanassi S, Weber DG, Abu-Zidan FM, Campanile FC, Di Saverio S, Baiocchi GL, Casella C, Kelly MD, Kirkpatrick AW, Leppaniemi A, Moore EE, Peitzman A, Fraga GP, Ceresoli M, Maier RV, Wani I, Pattonieri V, Perrone G, Velmahos G, Sugrue M, Sartelli M, Kluger Y, Catena F. Perforated and bleeding peptic ulcer: WSES guidelines. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 31.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Kavitt RT, Lipowska AM, Anyane-Yeboa A, Gralnek IM. Diagnosis and Treatment of Peptic Ulcer Disease. Am J Med. 2019;132:447-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2017;390:613-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 399] [Cited by in RCA: 606] [Article Influence: 67.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (37)] |

| 89. | Wong SH, Sung JJ. Management of GI emergencies: peptic ulcer acute bleeding. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:639-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Sugimoto M, Furuta T. Efficacy of esomeprazole in treating acid-related diseases in Japanese populations. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2012;5:49-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Joo MK, Park CH, Kim JS, Park JM, Ahn JY, Lee BE, Lee JH, Yang HJ, Cho YK, Bang CS, Kim BJ, Jung HK, Kim BW, Lee YC; Korean College of Helicobacter Upper Gastrointestinal Research. Clinical Guidelines for Drug-Related Peptic Ulcer, 2020 Revised Edition. Gut Liver. 2020;14:707-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Lai KC, Lam SK, Chu KM, Wong BC, Hui WM, Hu WH, Lau GK, Wong WM, Yuen MF, Chan AO, Lai CL, Wong J. Lansoprazole for the prevention of recurrences of ulcer complications from long-term low-dose aspirin use. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:2033-2038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Chan FK, Ching JY, Suen BY, Tse YK, Wu JC, Sung JJ. Effects of Helicobacter pylori infection on long-term risk of peptic ulcer bleeding in low-dose aspirin users. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:528-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Chan FK, Chung SC, Suen BY, Lee YT, Leung WK, Leung VK, Wu JC, Lau JY, Hui Y, Lai MS, Chan HL, Sung JJ. Preventing recurrent upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection who are taking low-dose aspirin or naproxen. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:967-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 445] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ji KY, Hu FL. Interaction or relationship between Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in upper gastrointestinal diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3789-3792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Liao EC, Yu CH, Lai JH, Lin CC, Chen CJ, Chang WH, Chien DK. A pilot study of non-invasive diagnostic tools to detect Helicobacter pylori infection and peptic ulcer disease. Sci Rep. 2023;13:22800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Abrignani MG, Gatta L, Gabrielli D, Milazzo G, De Francesco V, De Luca L, Francese M, Imazio M, Riccio E, Rossini R, Scotto di Uccio F, Soncini M, Zullo A, Colivicchi F, Di Lenarda A, Gulizia MM, Monica F. Gastroprotection in patients on antiplatelet and/or anticoagulant therapy: a position paper of National Association of Hospital Cardiologists (ANMCO) and the Italian Association of Hospital Gastroenterologists and Endoscopists (AIGO). Eur J Intern Med. 2021;85:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Kawai T, Oda K, Funao N, Nishimura A, Matsumoto Y, Mizokami Y, Ashida K, Sugano K. Vonoprazan prevents low-dose aspirin-associated ulcer recurrence: randomised phase 3 study. Gut. 2018;67:1033-1041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 99. | Mizokami Y, Oda K, Funao N, Nishimura A, Soen S, Kawai T, Ashida K, Sugano K. Vonoprazan prevents ulcer recurrence during long-term NSAID therapy: randomised, lansoprazole-controlled non-inferiority and single-blind extension study. Gut. 2018;67:1042-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Dong Y, Xu H, Zhang Z, Zhou Z, Zhang Q. Comparative efficiency and safety of potassium competitive acid blockers versus Lansoprazole in peptic ulcer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1304552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Chinzon D, Moraes-Filho JPP, Domingues G, Guedes JLS, Santos CY, Zaterka S. Vonoprazan in the management of erosive oesophagitis and peptic ulcer-induced medication: a systematic review. Prz Gastroenterol. 2022;17:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Geeratragool T, Kaosombatwattana U, Boonchote A, Chatthammanat S, Preechakawin N, Srichot J, Sudcharoen A, Sirisunhirun P, Termsinsuk P, Rugivarodom M, Limsrivilai J, Maneerattanaporn M, Pausawasdi N, Leelakusolvong S. Comparison of Vonoprazan Versus Intravenous Proton Pump Inhibitor for Prevention of High-Risk Peptic Ulcers Rebleeding After Successful Endoscopic Hemostasis: A Multicenter Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Gastroenterology. 2024;167:778-787.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Wang WX, Li RJ, Li XF. Efficacy and Safety of Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers vs Proton Pump Inhibitors for Peptic Ulcer Disease or Postprocedural Artificial Ulcers: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2024;15:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Ouyang M, Zou S, Cheng Q, Shi X, Zhao Y, Sun M. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers vs. Proton Pump Inhibitors for Peptic Ulcer with or without Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2024;17:698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Kim HU. Diagnostic and Treatment Approaches for Refractory Peptic Ulcers. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:285-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |