Published online Mar 5, 2026. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.111833

Revised: August 21, 2025

Accepted: January 6, 2026

Published online: March 5, 2026

Processing time: 216 Days and 4 Hours

Stricture formation in Crohn’s disease (CD) poses a significant clinical challenge, often requiring differentiation between inflammatory and fibrotic components to guide appropriate therapy.

To evaluate the utility of multimodal intestinal ultrasound - including small inte

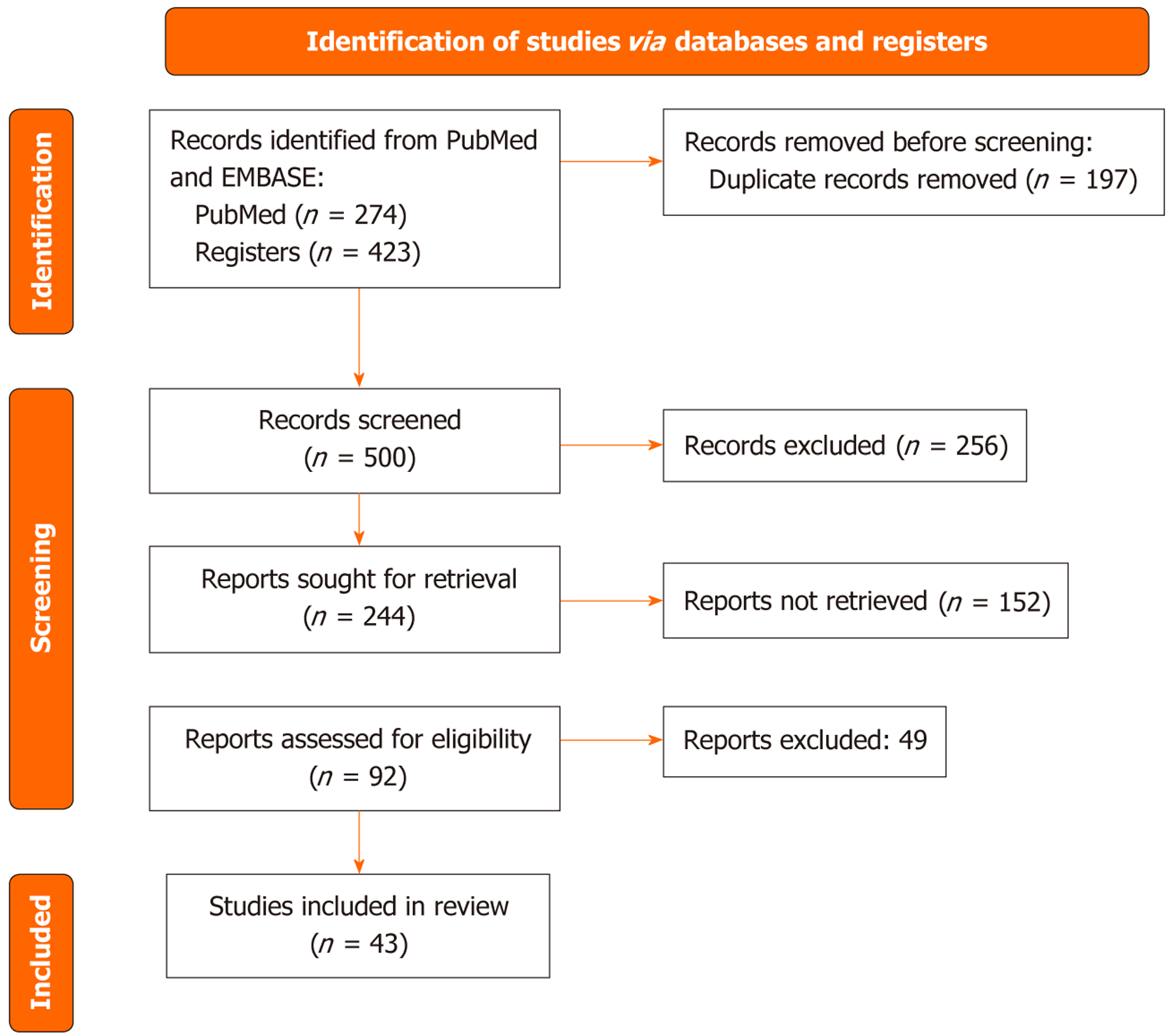

A review was conducted in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Sys

Across heterogeneous study designs, SICUS demonstrated high sensitivity for stricture detection (typically approximately 88%-98%) with specificity that varied by cohort and criteria. Common thresholds included bowel wall thickness > 3 mm, luminal narrowing < 1 cm, and/or prestenotic dilation > 2.5 cm. CEUS effectively distinguished fibrotic from inflammatory strictures using time-intensity curve metrics: Fibrotic strictures showed reduced peak enhancement (e.g., 25 dB vs 38 dB), and lower perfusion area under the curve (AUC) values (e.g., 570 intensity time units vs 1168 intensity time units), reflecting diminished vascularity. Cutoffs such as peak enhancement < 30 dB and AUC < 700 units were associated with fibrosis. Elastography - particularly shear wave elastography achieved AUCs of 0.88-0.91 for fibrosis detection using cutoffs of 2.5-2.9 m/second (sensitivity 80%-88%, specificity 85%-100%). Strain ratio thresholds between 2.2 and 3.0 also differentiated fibrotic from inflammatory lesions with diagnostic AUCs up to 0.91. Among elastog

Multimodal intestinal ultrasound - including SICUS, CEUS, and elastography - offers a comprehensive, radiation-free framework to detect, localize, and phenotype CD strictures. While performance is promising, variability in thresholds and reference standards limits generalizability. Standardized acquisition, predefined cut-offs, and mul

Core Tip: Multimodal intestinal ultrasound - including contrast-enhanced ultrasound, small intestine contrast ultrasonography, and ultrasound-based elastography - offers a noninvasive, radiation-free, and accurate approach to characterize Crohn’s disease strictures. Small intestine contrast ultrasonography reliably detects strictures and disease extent with performance comparable to cross-sectional imaging. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound perfusion parameters such as peak enhancement and AUC help differentiate inflammation from fibrosis, especially when combined with elastography. Shear wave elastography provides quantitative stiffness assessment, with velocities > 2.5 m/second indicating fibrosis. These tools support precise stricture phenotyping and may guide tailored therapy and surgical decision-making.

- Citation: Pal P, Kata P, Mateen MA, Ankam VK, Jha DL, Gupta R, Tandan M, Duvvur NR. Multimodality ultrasound in Crohn’s disease strictures. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2026; 17(1): 111833

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v17/i1/111833.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v17.i1.111833

Stricture formation is a common and clinically significant complication of Crohn’s disease (CD), affecting up to 30%-50% of patients within 10 years of diagnosis. These strictures often lead to obstructive symptoms, reduced quality of life, and surgical interventions. However, not all strictures behave the same: While inflammatory strictures may respond to medical therapy, fibrotic strictures typically require endoscopic or surgical intervention. Accurately distinguishing between these phenotypes is essential to avoid overtreatment, delay in surgery, or ineffective biologic therapy. As tran

Despite the widespread use of cross-sectional imaging modalities like magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) and computed tomography (CT) enterography, their ability to distinguish inflammation from fibrosis remains limited, with variability in both interpretation and correlation with histology. Endoscopy provides mucosal views but fails to assess mural or extramural features such as prestenotic dilation, fistulae, or mesenteric changes. Moreover, repeated use of radiation-based techniques is undesirable, particularly in younger or treatment-naïve patients. A reliable, accessible, and reproducible bedside tool for noninvasive stricture characterization - especially for routine monitoring and postoperative assessment - remains an important clinical gap[2].

This review explores the role of multimodal intestinal ultrasound (IUS), including small intestine contrast ultrasonography (SICUS), contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS), and ultrasound elastography, in the detection and phenotyping of CD strictures. By synthesizing evidence across studies, it attempts to highlight diagnostic thresholds, comparative accuracy with gold standards, and emerging biomarkers such as perfusion kinetics and stiffness metrics. The review aims to support clinicians in adopting validated ultrasound techniques for individualized, radiation-free, and cost-effective assessment of CD strictures across diverse clinical scenarios.

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews 2020 guidelines. No protocol was registered a priori. Eli

From 697 records, 43 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Study designs included prospective/retrospective cohorts, surgical validation, and ex vivo analyses. Reference standards comprised surgery/histology, MRE/CT enterography (CTE), endoscopy, and clinical follow-up. Tables 1, 2, and 3 summarize key characteristics (design, setting/centers, sample size), index test definitions and cut-offs, reference standards, and diagnostic accuracy.

| Ref. | Design | Number | Reference standard | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Definition (if stated) | Comparator modality (if any) | Kappa (if any) | Comments/additional findings |

| Calabrese et al[7], 2013 | Prospective comparative study | 38 | Surgical and histopathological findings | 95.5 | 80 | Lumen < 1 cm or upstream dilation > 2.5 cm with wall thickening | CT-enteroclysis | Not reported | High correlation with surgical lesion extent (ρ = 0.83) |

| Onali et al[8], 2012 | Prospective validation | 13 | Surgical and histological findings | 92 | Not separately stated | Wall thickening + lumen narrowing ± prestenotic dilation | CT-enteroclysis | Not reported | Feasible in all patients; comparable to CTE for all complications |

| Parente et al[4], 2004 | Prospective cohort | 102 | Barium enteroclysis, ileocolonoscopy | 89 | 93 | Stiff wall, lumen narrowing + upstream dilation | Conventional US, BE | 0.95 (for expert vs reference) | PEG-enhanced US improved sensitivity, reduced interobserver variability |

| Calabrese et al[14], 2009 | Prospective postoperative study | 72 | Ileocolonoscopy (Rutgeerts’ score) | 92.5 | 20 | BWT > 3 mm, lumen < 1 cm ± dilation > 2.5 cm | None | Not stated | BWT correlated with endoscopic recurrence (r = 0.67) |

| Calabrese et al[5], 2005 | Prospective comparative study | 38 | Surgical/histological findings | 95 | 80 | Wall thickening, lumen < 1 cm, ± dilation > 2.5 cm | CT-enteroclysis | Not reported | High correlation with extent of disease (ρ = 0.83) |

| Pallotta et al[13], 2012 | Prospective study vs surgical findings | 49 | Surgical/pathology | 97.5 | 100 | Lumen < 1 cm, wall thickening, ± dilation > 2.5 cm | IUS | 0.93 | Also reported fistula (96%) and abscess (100%) accuracy |

| Kumar et al[10], 2014 | Retrospective comparative study | 25 | Intraoperative findings | 88 | 88 | Wall thickening + fixed loop or absence of peristalsis | MRE | 0.73 | Substantial agreement with MRE and surgery |

| Chatu et al[6], 2012 | Retrospective | 52 | Multimodal including surgery | 88 | Not stated | Wall thickening + narrowed lumen | CT/MRE | Not reported | SICUS helped define disease extent and complications |

| Aloi et al[11], 2015 | Pediatric prospective cohort | 26 | MRE | 85.7 | 100 | Not precisely defined | MRE | 0.82 | High agreement between modalities |

| Ref. | Study design | n (CD strictures) | CEUS modality | Reference standard | Key findings |

| Goertz et al[25], 2018 | Prospective cohort | 30 | Quantitative CEUS (peak enhancement, AUC, TTP) | Surgery or clinical follow-up | CEUS correlated well with histological fibrosis; peak enhancement and AUC were lower in fibrotic vs inflammatory strictures |

| Horjus Talabur Horje et al[21], 2015 | Prospective observational | 30 | CEUS with dynamic perfusion analysis | Surgical pathology | CEUS showed correlation with fibrosis; fibrotic strictures had lower contrast uptake |

| Servais et al[22], 2021 | Prospective cohort | 34 | Qualitative CEUS, quantitative (AUC, TTP, PI) | Histopathology | Combined CEUS + elastography improved diagnostic accuracy for fibrostenotic vs inflammatory |

| Wilkens et al[20], 2018 | Prospective diagnostic accuracy study | 25 | Quantitative CEUS | Surgery | Moderate accuracy in distinguishing fibrosis; combined CEUS + DCE-MRE showed complementary roles |

| Lu et al[2], 2022 | Prospective study | 40 | CEUS and SWE | Histology | CEUS parameters and shear wave velocity discriminated fibrosis; AUC and PE were reduced in fibrotic strictures |

| Ma et al[16], 2020 | Prospective study | 20 | Quantitative CEUS + elastography | CT and endoscopy | CEUS differentiated inflammatory vs fibrotic stenosis; AUC and PE were higher in the inflammatory group |

| Nylund et al[24], 2013 | Pilot feasibility study | 15 | Quantitative CEUS | Endoscopy | CEUS is feasible and safe; potential for stricture characterization; inflammation showed higher perfusion |

| Quaia et al[17], 2018 | Prospective pilot study | 20 | Visual CEUS + strain elastography | Histopathology | Combined CEUS + elastography improved accuracy (AUC up to 0.95); good inter-reader agreement |

| Serra et al[18], 2017 | Prospective study | 29 | CEUS + strain elastography | Histology | No correlation between CEUS parameters and histologic fibrosis; overlap of inflammation and fibrosis |

| Sidhu et al[19], 2023 | Prospective pediatric study | 25 (11 surgical) | CEUS + SWE | Surgical pathology | CEUS AUC correlated with fibrosis and muscular hypertrophy; it helped identify candidates for surgery |

| Ripollés et al[26], 2013 | Prospective observational | 28 | B-mode, CDI, CEUS with PME and TTP analysis | Surgical specimens | PME correlated with inflammatory activity; CEUS showed low PME in fibrotic strictures |

| Schirin-Sokhan et al[29], 2011 | Pilot prospective | 18 | Quantitative CEUS with QONTRAST software | Endoscopy + histology + follow-up | No significant correlation between quantitative CEUS and histologic fibrosis; Limberg score and CDAI better correlated with inflammation |

| Wilkens et al[28], 2022 | Prospective cohort | 18 | CEUS + DCE-MRE + elastography | Biomechanical stiffness ex vivo | CEUS perfusion did not correlate with stricture stiffness; DCE-MRE slope correlated better with mechanical stiffness |

| Ponorac et al[27], 2021 | Prospective single-center | 24 | Quantitative CEUS (PI, TTP, AUC) | Surgical pathology | Lower AUC and TTP values in fibrotic strictures; CEUS is useful in stricture phenotype classification |

| Quaia et al[23], 2012 | Prospective pilot | 28 | CEUS with PME, wash-in slope | Endoscopy + MRE | PME is significantly lower in fibrostenotic than in inflammatory strictures; good intraobserver reproducibility |

| Ref. | Study design | n (CD strictures) | Elastography modality | Reference standard | Key findings |

| Abu-Ata et al[37], 2023 | Prospective | 33 | SWE | Histology | SWE cut-off > 2.5 m/second had 80% sensitivity, 85% specificity; good fibrosis correlation |

| Baumgart et al[30], 2015 | Ex vivo study | 16 | Strain elastography | Histology, tensiometry | Strain 1.56 (fibrotic) vs 3.74 (non-fibrotic), P < 0.0001; correlated with collagen |

| Chen et al[31], 2023 | Prospective | 52 | SWE | Histology | ρ = 0.74 with fibrosis; SWE differentiated fibrosis with high accuracy |

| Dillman et al[41], 2014 | Ex vivo | 12 | Strain elastography | Histology | Inverse correlation with fibrosis grade (ρ = -0.66), hydroxyproline (ρ = -0.72) |

| Ding et al[39], 2019 | Prospective | 25 | SE, ARFI, pSWE | Histology | pSWE AUC = 0.833; SWE superior to SE/ARFI in fibrosis detection |

| Fraquelli et al[33], 2015 | Prospective | 47 | Strain elastography | Histology | SR: 2.64 (severe) vs 1.16 (mild/no fibrosis), AUC = 0.91 |

| Fufezan et al[38], 2015 | Pilot pediatric | 24 | SWE | Clinical indices | Higher SWE values with more active disease; a scoring system proposed |

| Lu et al[2], 2022 | Prospective | 40 | SWE + CEUS | Histology | SWE + CEUS showed distinct profiles for fibrosis vs inflammation |

| Ma et al[16], 2020 | Prospective | 20 | SWE + CEUS | CT/endoscopy | SWE and CEUS parameters significantly differed in fibrotic vs inflammatory groups |

| Matsumoto et al[36], 2023 | Prospective | 21 | SWE | IUS + clinical | SWE decreased only in ustekinumab group (P = 0.028); tracked stiffness after biologics |

| Mazza et al[34], 2022 | Prospective | 31 | RTE | Histology + MRE | SR AUC = 0.88 for fibrosis; RTE outperformed MRE delayed enhancement (AUC = 0.61) |

| Orlando et al[35], 2018 | Prospective | 34 | Strain elastography | Histology | SR > 2.52 predicted fibrosis with 90% sensitivity, 88% specificity |

| Sconfienza et al[32], 2016 | Prospective | 18 | Axial strain sonoelastography | Histology | Improved fibrosis detection vs MRE; better visual pattern recognition |

| Serra et al[18], 2017 | Prospective | 29 | Strain elastography | Histology | No correlation between SR and fibrosis; overlapping inflammation/fibrosis |

| Sidhu et al[19], 2023 | Prospective pediatric | 25 | SWE + CEUS | Surgery | SWE + CEUS identified fibrosis/muscular hypertrophy; helpful for surgical planning |

| Stidham et al[40], 2011 | Animal + ex vivo | 31 | Strain UEI | Histology, tensiometry | UEI strain -2.07 (inflamed) vs -1.10 (fibrotic), Young’s modulus 2.75 kPa vs 0.3 kPa |

| Zhang et al[42], 2023 | Retrospective | 37 | SWE | Histology | Emean > 21.3 kPa AUC = 0.877 for fibrosis; SWE stronger fibrosis correlation vs CTE |

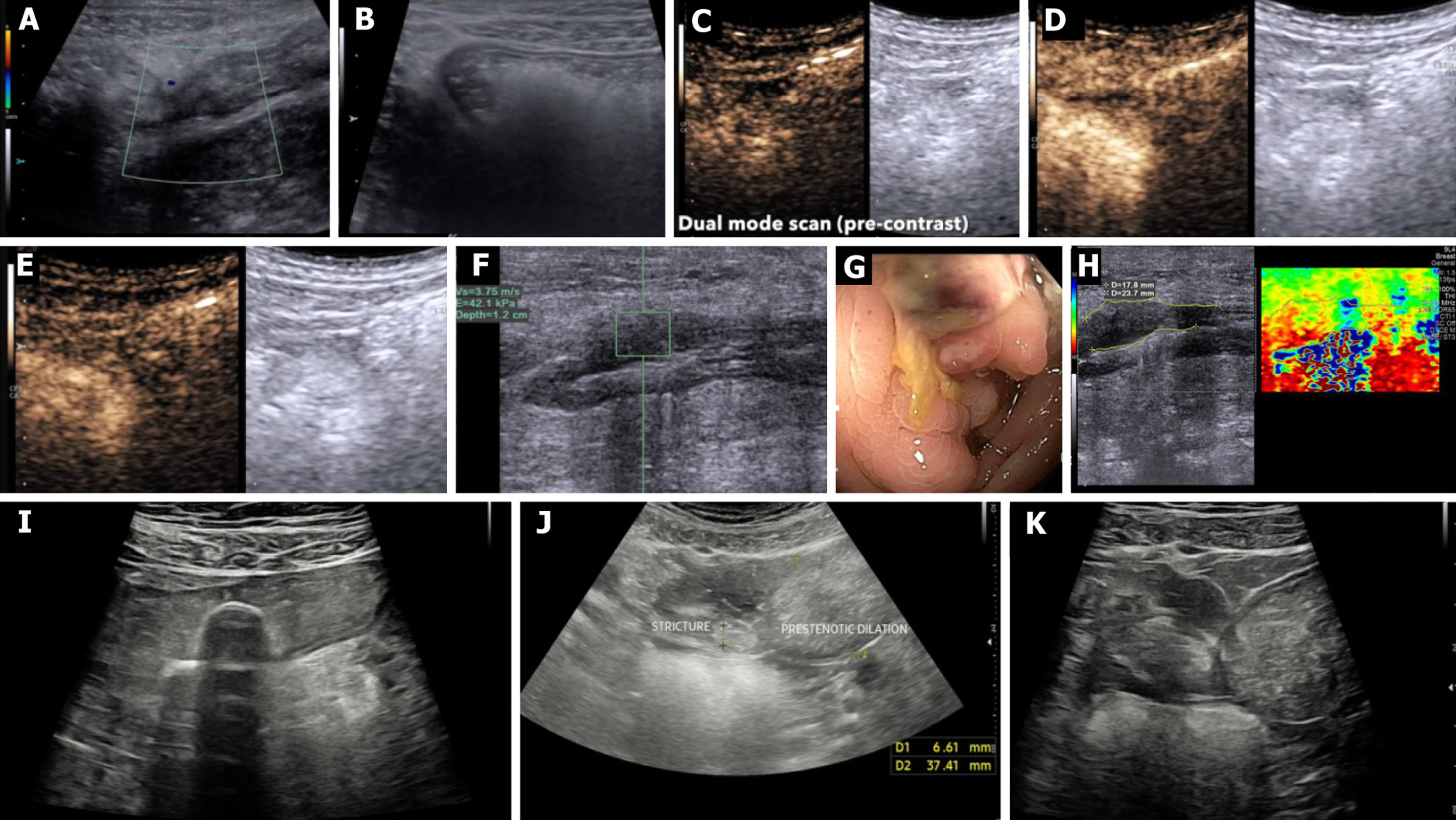

SICUS consistently detected strictures and disease extent with high sensitivity (typically approximately 88%-98%) and context-dependent specificity, with commonly used definitions including bowel wall thickness (BWT) > 3 mm, luminal diameter < 1 cm, and/or prestenotic dilation > 2.5 cm. CEUS differentiated perfusion profiles of inflammatory vs fibrotic strictures using time-intensity curve (TIC) metrics [e.g., peak enhancement (PE) and area under the curve (AUC)], and complemented B (Brightness)-mode. Elastography - particularly shear wave elastography (SWE) - quantified stiffness and correlated with histologic fibrosis in several surgical validation cohorts; commonly reported thresholds for fibrosis ranged around shearwave velocity approximately 2.5-2.9 m/second or strain-ratio approximately > 2.2-3.0.

SICUS is a non-invasive, radiation-free imaging modality developed to overcome the limitations of conventional transabdominal ultrasound (TAS) in evaluating small bowel lesions, particularly in CD (Table 1). By administering an oral anechoic contrast solution (typically 30 minutes after injection of polyethylene glycol 500 mL), SICUS achieves uniform small bowel distension, improving loop separation and wall visibility from the duodenojejunal flexure to the ileocecal valve. This enables better delineation of disease extent, mural abnormalities, and complications such as strictures, pre

In a pivotal pediatric study by Pallotta et al[3], SICUS demonstrated superior diagnostic accuracy compared to TAS and comparable performance to radiological standards [small bowel follow-through (SBFT)]. SICUS achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity for detecting small bowel CD in undiagnosed patients and 96% sensitivity and 100% specificity in those with established disease. It also outperformed IUS in identifying both proximal (93% vs 50%) and distal (97% vs 83%) small bowel involvement, with almost perfect agreement with SBFT (κ = 0.93). Additionally, SICUS accurately assessed the length of lesions (mean 23 cm), with a strong correlation to radiology (r = 0.86), while TUS significantly underestimated disease extent. Notably, SICUS identified small bowel strictures with 94% sensitivity, compared to 70% with TUS, and detected strictures missed by both TUS and SBFT, including jejunal lesions confirmed at surgery[3]. These findings establish SICUS as a first-line tool in the evaluation and follow-up of CD, especially in pediatric populations where ra

Several prospective studies (Table 1) have compared SICUS to traditional modalities such as SBFT, small bowel enema (SBE), and ileocolonoscopy (IC), particularly for evaluating small bowel strictures in CD. In a pivotal prospective study involving 102 patients, Parente et al[4] demonstrated that SICUS achieved higher sensitivity for detecting strictures (89%) compared to conventional ultrasound (74%) and showed excellent correlation with barium enteroclysis for assessing disease extent (r = 0.94). Importantly, SICUS also improved interobserver agreement and significantly reduced variability in BWT and lesion localization[4]. The study concluded that SICUS was comparable to barium enteroclysis in characterizing lesion location and extent, while offering the added advantages of reduced cost, improved tolerability, and no radiation exposure.

In another prospective head-to-head comparison, Calabrese et al[5] evaluated SICUS against conventional TAS and SBE in 40 patients with CD. SICUS had a sensitivity of 94% for detecting strictures compared to 78% with SBE, and it provided more accurate estimates of disease extent (mean stricture length 15.7 cm vs 12.4 cm with SBE, P < 0.05). SICUS also performed better in detecting multiple strictures and assessing bowel elasticity, which could help distinguish fibrotic from inflammatory stenosis. The overall agreement for stricture detection between SICUS and intraoperative findings was stronger than with SBE, confirming its clinical reliability.

Chatu et al[6] conducted a large retrospective United Kingdom study including 143 patients who underwent SICUS and were compared against SBFT, CT, histology, and IC. SICUS demonstrated 93% sensitivity and 99% specificity for detecting small bowel CD, with kappa agreement coefficients of 0.88 with SBFT and 0.91 with CT. Among patients with strictures, SICUS identified all cases confirmed by SBFT or CT, and in two cases, it revealed additional pathology missed by SBFT. The agreement between SICUS and histology (k = 0.62) was also notable, outperforming C-reactive protein (k = 0.07) as a surrogate of disease activity. Additionally, SICUS provided valuable data in patients with prior resections and helped in surgical decision-making when IC was incomplete or inconclusive[6]. Collectively, these studies underscore SICUS as a highly accurate, non-invasive alternative to SBFT and SBE, with better tolerability, no radiation, and the added benefit of detecting both mural and transmural disease characteristics. While IC remains essential for mucosal evaluation and histology, SICUS offers critical complementary information, particularly for detecting fibrostenotic disease and proximal small bowel involvement that may be inaccessible to endoscopy.

Several studies (Table 1) have directly compared SICUS with CTE for the characterization of strictures in CD, consistently demonstrating comparable diagnostic performance. In a prospective study of 59 patients, Calabrese et al[7] reported that SICUS identified ileal strictures with 95.5% sensitivity, 80% specificity, and 91.5% diagnostic accuracy, with strong correlation to CTE in assessing both BWT (ρ = 0.79) and disease extent (ρ = 0.89). Notably, the correlation between SICUS and surgical measurements of disease length (ρ = 0.83) was higher than that of CTE (ρ = 0.68), suggesting better surgical concordance[7]. Similarly, in a surgical validation study, Onali et al[8] found that both SICUS and CTE detected strictures in nearly all patients, with SICUS slightly outperforming CTE for identifying prestenotic dilation (85% vs 82%) and achieving equivalent accuracy for detecting fistulas and abscesses. Chatu et al[6] supported these findings in a real-world UK cohort, reporting strong agreement between SICUS and CT (κ = 0.91) for detecting small bowel CD and strictures, with SICUS identifying all strictures that were also detected by CT and proving useful even when CT was inconclusive. These data collectively affirm that SICUS matches CTE in stricture detection and extent characterization, with the add

Multiple studies (Table 1) have demonstrated that SICUS performs comparably to MRE in detecting and characterizing strictures in CD. In a prospective pediatric study, Hakim et al[9] reported substantial agreement between SICUS and MRE in identifying strictures (κ = 0.77), proximal and distal disease location (κ = 0.78-0.87), and upstream dilatation (κ = 0.68), with SICUS detecting some dilatations missed by MRE. Kumar et al[10], in a surgical validation study, showed that SICUS achieved a sensitivity of 87.5% and κ = 0.73 for strictures compared to surgical findings, while MRE demonstrated slightly higher sensitivity (100%) and κ = 0.88. However, SICUS had superior sensitivity for detecting fistulae (88% vs 67%), bowel wall thickening (95% vs 82%), and dilatation (100% vs 67%) compared to MRE. Notably, the concordance between SICUS and MRE was almost perfect for identifying strictures and their number/Location (κ = 0.84-0.85), and substantial for mucosal thickening and fistulae (κ = 0.61-0.65)[10]. In a pediatric comparison by Aloi et al[11], SICUS and MRE were both effective in detecting ileal and colonic involvement, with SICUS demonstrating higher sensitivity for jejunal disease (92% vs 75%), while MRE was slightly more sensitive in the mid and proximal ileum. Collectively, these findings suggest that SICUS is a valid, accurate, and radiation-free alternative to MRE for stricture characterization in both children and adults, particularly advantageous in routine and repeated assessments where patient tolerance or access to MRE may be limiting.

SICUS and small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) offer complementary strengths in the assessment of CD, with SICUS excelling in transmural and stricturing disease, and SBCE in mucosal lesion detection. In a prospective multicenter pediatric study, Aloi et al[11] found comparable diagnostic yields between SICUS and SBCE for detecting ileal invo

Both Pallotta et al[13] and Kumar et al[10] evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of SICUS against intraoperative findings in CD. In Pallotta’s prospective study of 49 surgical CD patients, SICUS demonstrated excellent sensitivity and specificity for detecting strictures (97.5%, 100%; κ = 0.93), fistulas (96%, 90.5%; κ = 0.88), and abscesses (100%, 95%; κ = 0.89), with strong agreement in stricture location and number. The extension of strictures measured by SICUS closely matched surgical values (6.6 cm vs 6.8 cm, not significant)[13]. Kumar et al’s retrospective study[10] (n = 25) yielded similarly high concordance: Sensitivity/specificity of 88% each for strictures (κ = 0.73), 86%/94% for fistulas (κ = 0.82), and 100%/95% for abscesses (κ = 0.87). Both studies confirm that SICUS reliably identifies and localizes CD-related complications - comparable to intraoperative assessment - supporting its use as a noninvasive, radiation-free, and accurate modality in the preoperative evaluation of complicated small bowel CD.

SICUS has demonstrated high diagnostic accuracy in detecting postoperative recurrence (POR) of CD when compared with IC, the current gold standard. In a prospective study of 72 patients, Calabrese et al[14] reported that SICUS had a sensitivity of 92.5%, positive predictive value of 94%, and accuracy of 87.5% for detecting POR. Importantly, SICUS findings such as increased BWT > 3 mm, stricture, and prestenotic dilation significantly correlated with Rutgeerts’ endoscopic scores (r = 0.67, P < 0.0001), with greater BWT and lesion extent observed in patients with advanced recurrence (scores ≥ 3). SICUS was especially valuable in patients with anastomotic stenosis, where it enabled visualization of the neoterminal ileum that was inaccessible to endoscopy[14]. Similarly, Castiglione et al[15] showed that oral contrast-enhanced sonography - a variant of SICUS - achieved 82% sensitivity and 94% specificity, with a BWT threshold ≥ 4 mm accurately distinguishing severe recurrence (grades 3-4) from mild or no recurrence. Both studies underscore SICUS’s ability to detect transmural and stenosing disease recurrence with high correlation to endoscopic severity grading, supporting its utility as a noninvasive, repeatable modality for postoperative surveillance, especially in patients who are asymptomatic, at high risk, or unwilling to undergo endoscopy.

Common SICUS criteria included BWT > 3 mm, luminal diameter < 1 cm, and/or prestenotic dilation > 2.5 cm; across surgical and radiologic validation cohorts, these definitions yielded sensitivity typically approximately 88%-98% with context-dependent specificity.

Several prospective studies (Table 2) have explored the role of CEUS in distinguishing inflammatory from fibrotic strictures in CD, with mixed results. Lu et al[2] demonstrated that CEUS parameters - particularly PE and AUC - were significantly reduced in fibrotic compared to inflammatory strictures, aligning well with histologic fibrosis scores. Similarly, Ma et al[16] found that CEUS combined with SWE could differentiate stricture phenotypes, with inflammatory lesions showing higher AUC and PE values. Quaia et al[17] also found that CEUS, especially when integrated with elastography, offered high diagnostic accuracy (AUC up to 0.95) in characterizing strictures, showing good interobserver agreement. In contrast, Serra et al[18] reported no significant correlation between CEUS enhancement patterns and histologic fibrosis grades; most strictures exhibited mixed inflammatory and fibrotic features, potentially confounding perfusion-based discrimination. Notably, in pediatric CD, Sidhu et al[19] observed significantly elevated AUC values on CEUS in patients requiring surgical resection, with strong correlation to muscularis propria hypertrophy and histologic fibrosis. Adding to this body of evidence, de Voogd et al[1] developed the Stricture Score Amsterdam by integrating B-mode ultrasound and CEUS parameters, including wash-in AUC and wall stratification loss, to accurately differentiate inflammatory and chronic strictures. The Stricture Score Amsterdam achieved an area under the receiver operating curve values of 0.88 and 0.90 for inflammatory and chronic phenotypes, respectively, with good interobserver agreement, underscoring CEUS’s reproducibility and added value beyond Doppler alone[1]. Together, these studies suggest that CEUS, particularly when integrated with structural and perfusion metrics, offers a valuable non-invasive tool in the mul

CEUS and MRE are increasingly employed to assess transmural disease in CD. Comparative studies show key dis

Quantitative analysis of CEUS using TICs offers valuable insight into the differentiation of inflammatory vs fibrotic Crohn’s strictures. Two key studies - Quaia et al[23] and Nylund et al[24] - demonstrate the diagnostic relevance of TIC-derived perfusion metrics. Quaia et al[23] found that inflammatory strictures showed significantly higher percentage of maximal enhancement and area under the enhancement curve (AUC) compared to fibrotic strictures (45.9% vs 37.3%, and 1168 vs 570, respectively; both P < 0.05), while time to PE was not significantly different[23]. Similarly, Nylund et al[24] used a pharmacokinetic modeling approach and reported that fibrotic segments had substantially lower absolute blood volume (0.9 mL/100 mL vs 3.4 mL/100 mL) and blood flow (22.6 mL/minute/100 mL vs 45.3 mL/minute/100 mL) than inflamed tissue, with no significant difference in mean transit time. These findings suggest that perfusion magnitude parameters (e.g., peak intensity, AUC, and flow) are more reliable than kinetic parameters [e.g., time to peak (TTP)] for fibrosis discrimination, and support the clinical utility of TIC-based CEUS quantification in evaluating Crohn’s strictures.

Quantitative CEUS offers valuable insight into treatment monitoring in CD, particularly through software-generated TIC analysis. Goertz et al[25] evaluated CEUS-derived parameters in patients undergoing vedolizumab therapy and found that amplitude-based parameters, such as PE and wash-in AUC, significantly decreased in clinical responders over 14 weeks, while remaining stable or increased in non-responders. Notably, the wash-in rate was the only parameter to show a statistically significant decline across all responders (P = 0.016), indicating its potential as a robust early biomarker of therapeutic efficacy. In contrast, time-derived parameters such as TTP, rise time, and fall time did not consistently correlate with clinical response[25]. These findings align with earlier studies demonstrating that amplitude-related perfusion metrics outperform timing parameters in differentiating inflammatory activity. Thus, CEUS TIC analysis - par

Several studies (Table 2) have investigated the relationship between CEUS parameters and histologic features of CD strictures, aiming to differentiate between inflammation and fibrosis. In a prospective surgical validation study, Serra et al[18] assessed CEUS, color Doppler, and real-time elastography (RTE) in resected bowel segments but found no significant correlation between CEUS perfusion patterns and histological scores of inflammation or fibrosis. Vascular signal intensity on CEUS also did not correlate with histologic vessel density, highlighting the limitations of qualitative CEUS for distinguishing fibrotic from inflammatory strictures in mixed lesions[18]. In contrast, Servais et al[22] applied TIC analysis and found that time-based CEUS parameters - specifically TTP and rise time - correlated well with histologic inflammation severity, achieving area under the receiver operating curves of 0.88 and 0.86, respectively. Although fibrosis was less consistently assessed due to the underrepresentation of low-fibrosis cases, the study demonstrated CEUS’s utility in identifying active inflammatory processes[22]. Ripollés et al[26] also observed that percentage enhancement increase was associated with histologic inflammation, while TTP inversely correlated with fibrosis, suggesting that perfusion delay may reflect transmural fibrotic remodeling. Additionally, Ponorac et al[27] reported a moderate correlation between quantitative CEUS perfusion metrics and histologic inflammation grades, although findings were tempered by variability in histologic scoring and sample size. Together, these studies suggest that while qualitative CEUS alone may have limited histologic concordance, quantitative TIC-derived parameters - especially time-based indices - offer meaningful correlation with inflammatory activity and may assist in the noninvasive characterization of CD strictures.

In a unique prospective ex vivo study, Wilkens et al[28] investigated whether CEUS and DCE-MRE could predict the biomechanical stiffness of CD strictures by comparing imaging features with direct mechanical testing on surgically resected intestinal specimens. The stiffness of the stricture, quantified as circumferential Young’s modulus, was signi

In a prospective pilot study, Schirin-Sokhan et al[29] investigated the ability of CEUS to differentiate inflammatory from fibrostenotic small bowel strictures in CD using a novel computerized algorithm. Eighteen patients with significant small bowel strictures underwent standardized CEUS with time-intensity curve analysis using QONTRAST software, alongside color Doppler and clinical evaluation. Despite reliable quantification of vascularity parameters - PE, TTP, and rise rate - none of these quantitative CEUS metrics showed significant correlation with the histologic or clinical classification of strictures. Instead, a composite “stenosis score” incorporating histology, Rutgeerts score, and therapeutic response was more reflective of stricture phenotype. Interestingly, semiquantitative measures such as the Limberg score and Crohn’s disease Activity Index were significantly associated with inflammatory stenosis, and a high CEUS rise rate was associated with earlier need for surgery in inflammatory cases[29]. This suggests that while CEUS-based perfusion metrics may not reliably distinguish fibrosis from inflammation at a single time point, they may hold prognostic value, particularly in str

Across studies using TIC analysis, lower PE (e.g., approximately ≤ 30 dB) and reduced perfusion AUC (e.g., approximately ≤ 700 intensity time units) were associated with fibrosis, whereas higher values suggested inflammatory activity.

Ultrasound-based elastography has been increasingly explored for differentiating fibrotic from inflammatory strictures in CD (Table 3). In a landmark study, Baumgart et al[30] demonstrated that RTE could detect increased stiffness in fibrotic bowel segments compared to unaffected tissue, showing a good correlation with surgical histology. Similarly, Chen et al[31] employed SWE and found that shear wave speed was significantly higher in fibrotic vs inflammatory strictures (2.78 m/second vs 1.59 m/second, P < 0.001), with a high AUC (AUC = 0.902) for fibrosis detection. Sconfienza et al[32] applied axial strain sonoelastography to classify strictures into elastic, intermediate, and stiff categories and observed a strong correlation with histologic fibrosis, highlighting its potential for preoperative stricture characterization. However, findings from Serra et al[18] were more cautious - while they attempted to correlate strain ratios (SRs) from RTE with histologic scores, no significant association was found, possibly due to high coexisting inflammation within fibrotic segments. Taken together, these studies suggest that while elastography - especially SWE and axial strain methods - holds promise for noninvasive fibrosis detection in CD strictures, results may vary by technique, operator, and disease phen

SR from RTE provides a semi-quantitative assessment of bowel wall stiffness and has been evaluated as a marker to differentiate fibrotic from inflammatory strictures in CD. In a prospective surgical validation study, Fraquelli et al[33] reported that SR values were significantly higher in patients with severe histologic fibrosis (median SR: 2.64) compared to those with mild or no fibrosis (median SR: 1.16), with an AUC of 0.91 for detecting high-grade fibrosis. Mazza et al[34] also demonstrated a strong correlation between SR and histological fibrosis score (r = 0.76), with mean SR values of 3.0 ± 0.5 in fibrotic segments vs 1.7 ± 0.4 in non-fibrotic ones, and found SR to outperform MRE-based fibrosis indices. In the study by Orlando et al[35], SR values were significantly higher in fibrostenotic strictures (mean SR: 3.18 ± 1.07) compared to predominantly inflammatory lesions (mean SR: 1.45 ± 0.58), with an optimal cut-off SR > 2.2 yielding a sensitivity of 83% and specificity of 88%. There was no improvement in strain ratio after anti-TNF therapy. Another study by Matsumoto et al[36], showed SWE indices did not change in the infliximab or bio-switch groups, while only the ustekinumab group showed a significant shear wave speed reduction. This likely reflects longstanding fibrosis in bio-switch patients and suggests that early ustekinumab may better suppress fibrotic progression, pending histological confirmation. In contrast, Serra et al[18] reported no statistically significant difference in SR across fibrosis grades, with overlapping values and poor correlation with histologic scores, possibly due to high coexisting inflammation and technical variability in strain measurement. Taken together, these findings suggest that SR thresholds between 2.2 and 3.0 may help discriminate fibrotic strictures in selected settings, but variability across studies underscores the need for technical standardization and multi-institutional validation before clinical adoption.

SWE has emerged as a promising quantitative tool to differentiate fibrotic from inflammatory strictures in CD. In a prospective study, Chen et al[31] demonstrated that fibrotic strictures exhibited significantly higher shear wave velocities (2.78 ± 0.53 m/second) than inflammatory ones (1.59 ± 0.41 m/second), with an AUC of 0.902 for fibrosis detection. Similarly, Lu et al[2] reported velocities of 3.43 ± 0.70 m/second in fibrotic segments vs 2.13 ± 0.60 m/second in inflammatory ones, alongside significantly higher Young’s modulus values (40.2 ± 7.3 kPa vs 22.2 ± 6.7 kPa), correlating well with histology[2]. Ma et al[16] supported these findings, showing shear wave speeds of 3.63 ± 0.86 m/second in fibrotic strictures and 2.51 ± 0.66 m/second in inflammatory ones, with parallel differences in elasticity modulus (42.1 ± 14.5 kPa vs 21.4 ± 8.8 kPa). Abu-Ata et al[37] also found SWE effective, distinguishing fibrotic (2.9 ± 0.6 m/second) from inflammatory strictures (1.7 ± 0.5 m/second) with strong histologic correlation. In pediatric CD, Fufezan et al[38] reported slightly elevated velocities in active disease (1.59 ± 0.27 m/second) compared to inactive (1.39 ± 0.24 m/second), suggesting SWE’s potential in pediatric monitoring. However, Sidhu et al[19] noted minimal SWE differences between fibrotic and inflammatory groups (1.26 m/second vs 1.23 m/second), though CEUS in the same study performed better. Based on current evidence, a shear wave velocity cut-off of approximately 2.5 m/second appears to distinguish fibrotic from inflammatory strictures in most adult studies, though variability across patient populations, techniques, and equi

Ding et al[39] conducted a prospective study comparing three ultrasound elastography techniques - strain elastography (SE), acoustic radiation force impulse (ARFI) imaging, and point SWE (p-SWE) - in 25 patients with suspected CD strictures. Histopathology was used as the reference standard. The results showed that p-SWE outperformed both SE and ARFI in distinguishing fibrotic from inflammatory strictures. Specifically, a shear wave velocity cut-off of 2.73 m/second yielded a sensitivity of 75%, specificity of 100%, accuracy of 96%, and an AUC of 0.833 (P < 0.05). In contrast, SE and

Several preclinical and ex vivo studies (Table 3) have validated ultrasound-based elastography for distinguishing fibrotic from inflammatory CD strictures. In a TNBS-induced rat colitis model, Stidham et al[40] demonstrated that TAS elasticity imaging could differentiate stricture phenotype, with significantly lower normalized strain in inflamed segments (-2.07 ± 0.71) compared to fibrotic segments (-1.10 ± 0.40, P < 0.05). These values correlated with ex vivo tensiometry: Fibrotic colon showed a Young’s modulus of 2.75 kPa vs 0.30 kPa in healthy control tissue (P < 0.01)[40]. Using ex vivo human ileal specimens, Baumgart et al[30] applied RTE and reported median strain values of 1.56 in fibrotic bowel vs 3.74 in non-fibrotic regions (P < 0.0001), correlating strongly with histological collagen deposition. Dillman et al[41] further confirmed this relationship in a blinded study using resected ileal specimens, showing that strain values from ultrasound elas

Multiple studies (Table 3) have explored the correlation between elastographic findings and histological measures of fibrosis and inflammation in CD strictures. Chen et al[31] demonstrated that SWE significantly differentiated fibrotic from inflammatory strictures, with higher mean shear wave velocities in fibrotic segments and a strong correlation with histologic fibrosis scores (ρ = 0.74, P < 0.001). Similarly, Abu-Ata et al[36] found that SWE velocity values correlated well with histological fibrosis grade, reporting a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 85% using a 2.5 m/second cut-off. Lu et al[2] further corroborated this association by integrating CEUS with SWE, noting that fibrotic segments had significantly higher stiffness values and lower enhancement, both of which aligned with histological scoring. On the SE side, Fraquelli et al[33] showed that the mean SR correlated inversely with fibrosis severity (SR: 2.3 ± 1.0 in mild vs 4.5 ± 1.4 in severe fibrosis, P < 0.01). However, Serra et al[18] reported no significant correlation between SR and histologic fibrosis (P = 0.877), possibly due to overlapping inflammation and fibrosis in many segments. In experimental validation, Stidham et al[39] used ex vivo tissue and rat models to confirm that ultrasound-based elasticity imaging could accurately differentiate inflammatory from fibrotic tissue, with strain values of -0.87 in fibrotic vs -1.99 in normal bowel (P = 0.0008), and strong inverse correlation with Young’s modulus (r = -0.81). Collectively, these findings suggest that while not universally con

Recent studies (Table 3) have highlighted that ultrasound elastography - particularly SWE - may provide greater specificity for detecting fibrosis compared to MRE or CTE. In a prospective study, Mazza et al[34] found that RTE SRs significantly correlated with histologic fibrosis (ρ = 0.63, P < 0.01), whereas delayed enhancement on MRE showed weaker correlation (ρ = 0.32, P = 0.09), suggesting RTE may outperform MRE in fibrosis detection. Similarly, Sconfienza et al[32] observed that axial strain sonoelastography could distinguish inflammatory from fibrotic strictures with greater clarity than MR findings, which were often limited by overlapping features. Zhang et al[42] directly compared SWE and CTE in 37 surgical CD cases: SWE showed strong correlation with fibrosis (r = 0.653), using a cut-off of 21.3 kPa (AUC: 0.877; sensitivity 88.9%, specificity 89.5%), while CTE correlated better with inflammation (r = 0.479), using a 4.5-point score (AUC: 0.766). When combined, SWE and CTE improved diagnostic accuracy (AUC: 0.918; specificity: 94.7%)[41]. These findings suggest that while CTE and MRE are valuable for detecting inflammation and complications, elastogra

In a large retrospective cohort of 225 patients presenting with chronic diarrhea, Kapoor et al[43] evaluated the utility of combining SWE and shear wave dispersion (SWD) with IUS for characterizing bowel wall abnormalities. Among 76 patients with thickened bowel walls, 33 had fibrotic strictures - 11 of which were due to CD. These fibrotic CD strictures demonstrated a mean Young’s modulus (E) of 33 kPa and SWD of 9 m/second/kHz, indicating stiff yet non-viscous bowel wall changes. This contrasted with inflammatory CD cases, which had high SWD (mean 19.5 m/second/kHz) and normal stiffness (E approximately 6.5 kPa), reflecting increased tissue viscosity without fibrosis. Mixed phenotype stri

Most adult cohorts reported shearwave velocity thresholds around 2.5-2.9 m/second indicating fibrosis, with sensitivities approximately 80%-88% and specificities ≈85%-100%; reported strainratio thresholds ranged approximately 2.2-3.0 in surgical validation studies.

This scoping review demonstrates that multimodal IUS, including SICUS, CEUS, and elastography, offers high diagnostic accuracy for detecting and characterizing CD strictures. SICUS consistently identified strictures and assessed disease extent with sensitivity ranging from 88% to 98%. CEUS provided valuable perfusion-based differentiation between inflammatory and fibrotic lesions, with PE < 30 dB and AUC < 700 units correlating with fibrosis. Elastographic moda

CEUS effectively identified perfusion differences between inflammatory and fibrotic strictures using TIC-derived parameters. While some studies showed conflicting histologic correlations, the integration of CEUS with elastography enhanced diagnostic accuracy. CEUS was particularly useful for therapy monitoring, with amplitude-based parameters (e.g., PE and wash-in AUC) reflecting biologic response[25]. Its role is complementary to MRE, offering bedside feasibility and radiation-free monitoring[20]. Among elastographic techniques, SWE emerged as the most reproducible and quantitatively robust modality, with strong correlation to histologic fibrosis and defined velocity thresholds[38]. SR also performed well in surgical validation studies but showed variability across operators and equipment[33]. Ex vivo and preclinical models supported the mechanistic basis of elastographic stiffness metrics, reinforcing their translational value[30,39].

The review included heterogeneous study designs, varied reference standards, and different ultrasound platforms, which may affect generalizability. Few studies employed standardized acquisition protocols or centralized image analysis. Histologic correlation, while strong in some studies, was not universally available or uniformly scored. Pediatric data were limited, and there is a lack of large, multicenter validation studies comparing all modalities head-to-head. Add

Future research should focus on multicenter prospective trials with histologic validation to standardize cutoff values and optimize acquisition protocols. Development of composite sonographic scores integrating B-mode, SICUS, CEUS, and elastographic features may enhance diagnostic precision. Training programs and certification in advanced IUS techniques should be promoted to improve operator consistency. With increasing evidence, multimodal IUS could become the frontline tool for stricture evaluation, replacing radiation-based imaging in selected scenarios. Technological advancements in artificial intelligence assisted analysis may further enhance its diagnostic capability. Included studies varied in patient selection, index definitions and thresholds, image acquisition platforms, and reference standards (surgery, histology, cross-sectional imaging, endoscopy, or clinical follow-up). Pediatric data were sparse, and few mul

Standardize CEUS TIC acquisition and reporting (PE, AUC) and define modality-specific cut-offs for fibrosis vs inflammation. Validate shear-wave elastography thresholds across vendors and body habitus; establish reference phantoms and quality metrics. Develop composite IUS scores integrating B-mode, SICUS, CEUS, and elastography, with surgical/histologic validation. Prioritize multicenter prospective cohorts with prespecified outcomes, blinded reads, and core lab analysis.

In conclusion, multimodal IUS, including SICUS, CEUS, and elastography, offers a comprehensive, radiation-free strategy for the detection and phenotyping of CD strictures. Each modality contributes unique diagnostic insights - from mural visualization and perfusion assessment to tissue stiffness quantification. With high accuracy, histologic correlation, and potential for real-time decision-making, these techniques support individualized management and improved outcomes in CD. Ongoing efforts toward standardization, validation, and dissemination are critical for widespread clinical adoption.

| 1. | de Voogd F, Beek KJ, Pruijt M, van Rijn K, van der Bilt J, Buskens C, Bemelman W, Neefjes-Borst A, Mookhoek A, D'Haens G, Stoker J, Gecse KB. Intestinal Ultrasound and Its Advanced Modalities in Characterizing Strictures in Crohn's Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;S1542-3565(25)00489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lu C, Gui X, Chen W, Fung T, Novak K, Wilson SR. Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography and Contrast Enhancement: Effective Biomarkers in Crohn's Disease Strictures. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:421-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pallotta N, Civitelli F, Di Nardo G, Vincoli G, Aloi M, Viola F, Capocaccia P, Corazziari E, Cucchiara S. Small intestine contrast ultrasonography in pediatric Crohn's disease. J Pediatr. 2013;163:778-84.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Parente F, Greco S, Molteni M, Anderloni A, Sampietro GM, Danelli PG, Bianco R, Gallus S, Bianchi Porro G. Oral contrast enhanced bowel ultrasonography in the assessment of small intestine Crohn's disease. A prospective comparison with conventional ultrasound, x ray studies, and ileocolonoscopy. Gut. 2004;53:1652-1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Calabrese E, La Seta F, Buccellato A, Virdone R, Pallotta N, Corazziari E, Cottone M. Crohn's disease: a comparative prospective study of transabdominal ultrasonography, small intestine contrast ultrasonography, and small bowel enema. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chatu S, Pilcher J, Saxena SK, Fry DH, Pollok RC. Diagnostic accuracy of small intestine ultrasonography using an oral contrast agent in Crohn's disease: comparative study from the UK. Clin Radiol. 2012;67:553-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calabrese E, Zorzi F, Onali S, Stasi E, Fiori R, Prencipe S, Bella A, Petruzziello C, Condino G, Lolli E, Simonetti G, Biancone L, Pallone F. Accuracy of small-intestine contrast ultrasonography, compared with computed tomography enteroclysis, in characterizing lesions in patients with Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:950-955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Onali S, Calabrese E, Petruzziello C, Zorzi F, Sica G, Fiori R, Ascolani M, Lolli E, Condino G, Palmieri G, Simonetti G, Pallone F, Biancone L. Small intestine contrast ultrasonography vs computed tomography enteroclysis for assessing ileal Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6088-6095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Hakim A, Alexakis C, Pilcher J, Tzias D, Mitton S, Paul T, Saxena S, Pollok R, Kumar S. Comparison of small intestinal contrast ultrasound with magnetic resonance enterography in pediatric Crohn's disease. JGH Open. 2020;4:126-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kumar S, Hakim A, Alexakis C, Chhaya V, Tzias D, Pilcher J, Vlahos J, Pollok R. Small intestinal contrast ultrasonography for the detection of small bowel complications in Crohn's disease: correlation with intraoperative findings and magnetic resonance enterography. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:86-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Aloi M, Di Nardo G, Romano G, Casciani E, Civitelli F, Oliva S, Viola F, Maccioni F, Gualdi G, Cucchiara S. Magnetic resonance enterography, small-intestine contrast US, and capsule endoscopy to evaluate the small bowel in pediatric Crohn's disease: a prospective, blinded, comparison study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:420-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Petruzziello C, Calabrese E, Onali S, Zuzzi S, Condino G, Ascolani M, Zorzi F, Pallone F, Biancone L. Small bowel capsule endoscopy vs conventional techniques in patients with symptoms highly compatible with Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;5:139-147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pallotta N, Vincoli G, Montesani C, Chirletti P, Pronio A, Caronna R, Ciccantelli B, Romeo E, Marcheggiano A, Corazziari E. Small intestine contrast ultrasonography (SICUS) for the detection of small bowel complications in crohn's disease: a prospective comparative study versus intraoperative findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:74-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Calabrese E, Petruzziello C, Onali S, Condino G, Zorzi F, Pallone F, Biancone L. Severity of postoperative recurrence in Crohn's disease: correlation between endoscopic and sonographic findings. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1635-1642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Castiglione F, Bucci L, Pesce G, De Palma GD, Camera L, Cipolletta F, Testa A, Diaferia M, Rispo A. Oral contrast-enhanced sonography for the diagnosis and grading of postsurgical recurrence of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1240-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ma C, Huang PL, Kang N, Zhang J, Xiao M, Zhang JY, Cao XC, Dai XC. The clinical value of multimodal ultrasound for the evaluation of disease activity and complications in inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9:4146-4155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Quaia E, Gennari AG, Cova MA, van Beek EJR. Differentiation of Inflammatory From Fibrotic Ileal Strictures among Patients with Crohn's Disease Based on Visual Analysis: Feasibility Study Combining Conventional B-Mode Ultrasound, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound and Strain Elastography. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2018;44:762-770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Serra C, Rizzello F, Pratico' C, Felicani C, Fiorini E, Brugnera R, Mazzotta E, Giunchi F, Fiorentino M, D'Errico A, Morselli-Labate AM, Mastroroberto M, Campieri M, Poggioli G, Gionchetti P. Real-time elastography for the detection of fibrotic and inflammatory tissue in patients with stricturing Crohn's disease. J Ultrasound. 2017;20:273-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sidhu SD, Joseph S, Dunn E, Cuffari C. The Utility of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound and Elastography in the Early Detection of Fibro-Stenotic Ileal Strictures in Children with Crohn's Disease. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2023;26:193-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wilkens R, Hagemann-Madsen RH, Peters DA, Nielsen AH, Nørager CB, Glerup H, Krogh K. Validity of Contrast-enhanced Ultrasonography and Dynamic Contrast-enhanced MR Enterography in the Assessment of Transmural Activity and Fibrosis in Crohn's Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:48-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Horjus Talabur Horje CS, Bruijnen R, Roovers L, Groenen MJ, Joosten FB, Wahab PJ. Contrast Enhanced Abdominal Ultrasound in the Assessment of Ileal Inflammation in Crohn's Disease: A Comparison with MR Enterography. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Servais L, Boschetti G, Meunier C, Gay C, Cotte E, François Y, Rozieres A, Fontaine J, Cuminal L, Chauvenet M, Charlois AL, Isaac S, Traverse-Glehen A, Roblin X, Flourié B, Valette PJ, Nancey S. Intestinal Conventional Ultrasonography, Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography in Assessment of Crohn's Disease Activity: A Comparison with Surgical Histopathology Analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2022;67:2492-2502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Quaia E, De Paoli L, Stocca T, Cabibbo B, Casagrande F, Cova MA. The value of small bowel wall contrast enhancement after sulfur hexafluoride-filled microbubble injection to differentiate inflammatory from fibrotic strictures in patients with Crohn's disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2012;38:1324-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nylund K, Jirik R, Mezl M, Leh S, Hausken T, Pfeffer F, Ødegaard S, Taxt T, Gilja OH. Quantitative contrast-enhanced ultrasound comparison between inflammatory and fibrotic lesions in patients with Crohn's disease. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:1197-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Goertz RS, Klett D, Wildner D, Atreya R, Neurath MF, Strobel D. Quantitative contrast-enhanced ultrasound for monitoring vedolizumab therapy in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a pilot study. Acta Radiol. 2018;59:1149-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ripollés T, Rausell N, Paredes JM, Grau E, Martínez MJ, Vizuete J. Effectiveness of contrast-enhanced ultrasound for characterisation of intestinal inflammation in Crohn's disease: a comparison with surgical histopathology analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ponorac S, Gošnak RD, Urlep D, Ključevšek D. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography in the evaluation of Crohn disease activity in children: comparison with histopathology. Pediatr Radiol. 2021;51:410-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wilkens R, Liao DH, Gregersen H, Glerup H, Peters DA, Buchard C, Tøttrup A, Krogh K. Biomechanical Properties of Strictures in Crohn's Disease: Can Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasonography and Magnetic Resonance Enterography Predict Stiffness? Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Schirin-Sokhan R, Winograd R, Tischendorf S, Wasmuth HE, Streetz K, Tacke F, Trautwein C, Tischendorf JJ. Assessment of inflammatory and fibrotic stenoses in patients with Crohn's disease using contrast-enhanced ultrasound and computerized algorithm: a pilot study. Digestion. 2011;83:263-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Baumgart DC, Müller HP, Grittner U, Metzke D, Fischer A, Guckelberger O, Pascher A, Sack I, Vieth M, Rudolph B. US-based Real-time Elastography for the Detection of Fibrotic Gut Tissue in Patients with Stricturing Crohn Disease. Radiology. 2015;275:889-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chen YJ, Mao R, Li XH, Cao QH, Chen ZH, Liu BX, Chen SL, Chen BL, He Y, Zeng ZR, Ben-Horin S, Rimola J, Rieder F, Xie XY, Chen MH. Real-Time Shear Wave Ultrasound Elastography Differentiates Fibrotic from Inflammatory Strictures in Patients with Crohn's Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2183-2190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Sconfienza LM, Cavallaro F, Colombi V, Pastorelli L, Tontini G, Pescatori L, Esseridou A, Savarino E, Messina C, Casale R, Di Leo G, Sardanelli F, Vecchi M. In-vivo Axial-strain Sonoelastography Helps Distinguish Acutely-inflamed from Fibrotic Terminal Ileum Strictures in Patients with Crohn's Disease: Preliminary Results. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2016;42:855-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fraquelli M, Branchi F, Cribiù FM, Orlando S, Casazza G, Magarotto A, Massironi S, Botti F, Contessini-Avesani E, Conte D, Basilisco G, Caprioli F. The Role of Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging in Predicting Ileal Fibrosis in Crohn's Disease Patients. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:2605-2612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mazza S, Conforti FS, Forzenigo LV, Piazza N, Bertè R, Costantino A, Fraquelli M, Coletta M, Rimola J, Vecchi M, Caprioli F. Agreement between real-time elastography and delayed enhancement magnetic resonance enterography on quantifying bowel wall fibrosis in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Orlando S, Fraquelli M, Coletta M, Branchi F, Magarotto A, Conti CB, Mazza S, Conte D, Basilisco G, Caprioli F. Ultrasound Elasticity Imaging Predicts Therapeutic Outcomes of Patients With Crohn's Disease Treated With Anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor Antibodies. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Matsumoto H, Hata J, Yo S, Sasahira M, Misawa H, Oosawa M, Handa O, Umegami E, Shiotani A. Serial Changes in Intestinal Stenotic Stiffness in Patients with Crohn's Disease Treated with Biologics: A Pilot Study Using Ultrasound Shear Wave Elastography. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2023;34:1006-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Abu-Ata N, Dillman JR, Rubin JM, Collins MH, Johnson LA, Imbus RS, Bonkowski EL, Denson LA, Higgins PDR. Ultrasound shear wave elastography in pediatric stricturing small bowel Crohn disease: correlation with histology and second harmonic imaging microscopy. Pediatr Radiol. 2023;53:34-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fufezan O, Asavoaie C, Tamas A, Farcau D, Serban D. Bowel elastography - a pilot study for developing an elastographic scoring system to evaluate disease activity in pediatric Crohn's disease. Med Ultrason. 2015;17:422-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ding SS, Fang Y, Wan J, Zhao CK, Xiang LH, Liu H, Pu H, Xu G, Zhang K, Xu XR, Sun XM, Liu C, Wu R. Usefulness of Strain Elastography, ARFI Imaging, and Point Shear Wave Elastography for the Assessment of Crohn Disease Strictures. J Ultrasound Med. 2019;38:2861-2870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Stidham RW, Xu J, Johnson LA, Kim K, Moons DS, McKenna BJ, Rubin JM, Higgins PD. Ultrasound elasticity imaging for detecting intestinal fibrosis and inflammation in rats and humans with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:819-826.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Dillman JR, Stidham RW, Higgins PD, Moons DS, Johnson LA, Keshavarzi NR, Rubin JM. Ultrasound shear wave elastography helps discriminate low-grade from high-grade bowel wall fibrosis in ex vivo human intestinal specimens. J Ultrasound Med. 2014;33:2115-2123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Zhang M, Xiao E, Liu M, Mei X, Dai Y. Retrospective Cohort Study of Shear-Wave Elastography and Computed Tomography Enterography in Crohn's Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kapoor A, Singh A, Kapur A, Mahajan G, Sharma S. Use of shear wave imaging with intestinal ultrasonography in patients with chronic diarrhea. J Clin Ultrasound. 2024;52:163-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/