Published online Sep 5, 2024. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97570

Revised: August 22, 2024

Accepted: August 28, 2024

Published online: September 5, 2024

Processing time: 92 Days and 15.3 Hours

Liver transplantation (LT) in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and chronic liver disease (CLD) is limited by factors such as tumor size, number, portal venous or hepatic venous invasion and extrahepatic disease. Although previously established criteria, such as Milan or UCSF, have been relaxed globally to accommodate more potential recipients with comparable 5-year outcomes, there is still a subset of the population that has advanced HCC with or without portal vein tumor thrombosis without detectable extrahepatic spread who do not qualify or are unable to be downstaged by conventional methods and do not qualify for liver transplantation. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) such as atezolizumab, pembrolizumab, or nivolumab have given hope to this group of patients. We completed a comprehensive literature review using PubMed, Google Scholar, reference citation analysis, and CrossRef. The search utilized keywords such as 'liver transplant', 'HCC', 'hepatocellular carcinoma', 'immune checkpoint inhibitors', 'ICI', 'atezolizumab', and 'nivolumab'. Several case reports have documented successful downstaging of HCC using the atezolizumab/bevaci

Core Tip: The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors as a downstaging therapy has been followed with great interest since the results of the IMBRAVE study, especially for multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma beyond criteria and certain cases with portal vein tumor thrombosis. Multiple case reports have shown benefit but with a degree of caution. Our review aims to identify the key points and recommendations for the safe usage of these life-saving immunomodulators in the setting of liver transplantation using the current available literature.

- Citation: Pahari H, Peer JA, Tripathi S, Singhvi SK, Dhir U. Downstaging of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma followed by liver transplantation using immune checkpoint inhibitors: Where do we stand? World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2024; 15(5): 97570

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2150-5349/full/v15/i5/97570.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4292/wjgpt.v15.i5.97570

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary liver cancer and is a leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, especially in patients with chronic liver disease[1,2]. Liver transplantation (LT) is considered a curative treat

Despite this expansion, a distinct subset of patients, particularly those with portal vein tumor thrombosis or multi-nodular HCC, have been unable to receive LT. The grim prognosis of such patients and the aggressive nature of the disease make conventional downstaging therapies infeasible. Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) and radiofrequency ablation (RFA) are examples of locoregional therapies that downsize HCC; however, the extent of the disease in these patients hinders the efficacy of such therapies[4,5].

Recent advancements in systemic therapy for HCC have introduced new possibilities for the downstaging of advanced HCC, particularly through immunotherapy. This includes immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) such as atezolizumab, a programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) inhibitor, and bevacizumab, a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor[6,7]. The combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab has become the new standard of care and has shown significant benefits for overall survival[8].

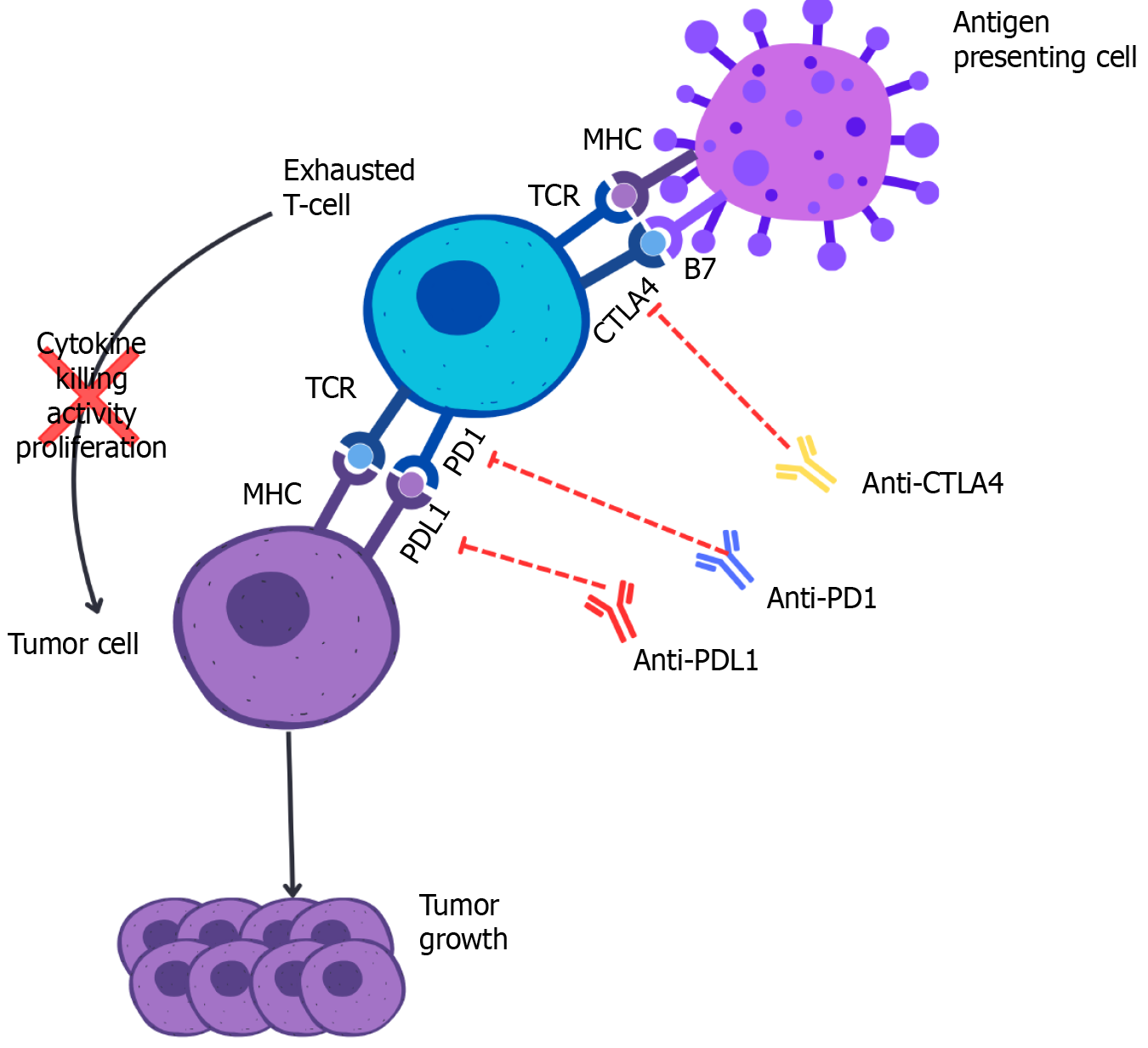

Although the advent of ICIs has provided a novel approach for advanced HCC management, there is limited evidence and no robust guidelines regarding the use of ICIs to downsize advanced HCC to meet LT parameters. Pre-transplant downstaging with ICIs awaits further evidence for approval; however, there is anecdotal evidence of an ICI-induced complete pathological response before LT[9]. As shown in Figure 1, the presence of ICI [antibodies against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), PD-1/PD-L1] in the chronic inflammatory or cirrhotic microenvironment has been demonstrated to establish immune exhaustion in HCC. The blockade of T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling or downstream signaling pathways of TCR impairs cytokine production, proliferative capacity, and antigen-induced killing of tumor cells by exhausted T cells. Furthermore, inhibition of TCR signaling with the major histocompatibility complex further optimizes host tumor growth. Immune exhaustion in HCC is primarily driven by the PD1/PDL1 pathway and CTLA-4 signaling[10]. In HCC, targeting these pathways through immune checkpoint inhibition, specifically blocking PDL1 and CTLA-4 increases the antitumor reaction against tumor cells, leading to significant downstaging.

This systematic review aimed to evaluate the current evidence regarding the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC prior to LT. We analyzed the outcomes, safety, and challenges associated with this therapeutic approach, providing insights into its potential role in expanding eligibility for LT among patients with advanced HCC. By synthesizing data from clinical studies, case reports, and real-world experiences, this review seeks to inform future research directions and clinical practices for managing advanced HCC with ICIs.

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using PubMed, Google Scholar, and CrossRef to gather relevant studies on the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC before LT. The search terms used were 'liver transplant', ‘HCC’, ‘hepatocellular carcinoma’, ‘immune checkpoint inhibitors’, ‘ICI’, ‘atezolizumab’, and 'nivolumab’. The search was limited to the articles published in English between January 2010 and May 2024. The reference lists of the identified articles were also reviewed to ensure the inclusion of other relevant studies.

Studies were included in the review if they met the following criteria: (1) Reported on the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC; (2) Included patients who underwent LT following ICI therapy; (3) Data on clinical outcomes such as tumor response, adverse effects, and post-transplant outcomes; and (4) Included case reports, case series, clinical trials, and observational studies.

Studies were excluded if they: (1) Were neither published in nor translated into English; (2) Did not provide sufficient details on the outcomes of ICI therapy; and (3) Were reviews, editorials, or opinion pieces without original data.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers. The following information was collected from each study. Study design and setting. Patient demographics and baseline characteristics. Details of ICI therapy, including the agents used, dosing, and duration. Downstaging outcomes, including tumor response rates and time to response. Adverse effects of ICI therapy, particularly immune-related adverse events. Details of liver transplantation, including the timing of post-ICI therapy, surgical outcomes, and post-transplant complications. Long-term outcomes, including recur

Discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion and consensus between the reviewers.

The quality of the included studies was assessed using criteria adapted from the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for clinical trials. The following factors were considered: Selection bias: The representativeness of the study population. Comparability: Adjusting for confounding variables. Outcome assess

Narrative synthesis was conducted because of the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of the study design, patient populations, and outcomes reported. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the baseline characteristics of the study population, treatment protocols, and clinical outcomes. The key findings are tabulated and discussed in the context of the existing literature.

For quantitative outcomes, such as tumor response rates and survival data, the results were pooled using a random-effects model when appropriate. The heterogeneity of the pooled studies was assessed using the I² statistic, with values greater than 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. Sensitivity analyses were performed to explore the impact of study quality and other potential sources of heterogeneity on the pooled estimates.

As this study involved a systematic review of published literature, no ethical approval was required. Ethical standards were maintained by accurately representing the findings of the included studies and acknowledging all sources.

Following this rigorous methodological approach, we aimed to provide a comprehensive and reliable synthesis of the current evidence regarding the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC before LT, addressing both the potential benefits and challenges associated with this therapeutic strategy.

Eight studies with different designs, patient populations, and clinical settings were included in this systematic review. These studies provide insights into the use of ICIs for the downstaging of advanced HCC before LT (Table 1). The reviewed studies demonstrate that ICIs can significantly downstage advanced HCC, making patients eligible for LT. Tabrizian et al[11] reported on nine patients treated with nivolumab before LT, where the majority experienced sub

| Ref. | Design | Sample size | ICIs used | Key findings |

| Tabrizian et al[11] | Case series | 9 | Nivolumab | Significant PD-L1 expression in donor allograft may indicate a subclinical all-immune response and identify patients at high risk of rejection |

| Chen et al[12] | Case report | 1 | Toripalimab | The effect of PD-1 antibody leads to the failure of the graft’s attempt to achieve “immune escape” by expressing PD-L1, which results in fatal acute rejection response |

| Nordness et al[13] | Case report | 1 | Nivolumab | Profound caution is needed when using nivolumab in patients with HCC who are either still awaiting or have previously undergone solid organ transplant. It is unclear given their mechanism of action, if a defined waiting period would be helpful before transplant |

| Kumar et al[14] | Case report | 1 | Atezolizumab, Bevacizumab | Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab effective as downstaging therapy for liver transplantation in HCC with PVTT |

| Aby et al[15] | Case report | 1 | Nivolumab | In carefully selected patients, ICI may serve as a bridge to LT |

| Chouik et al [16] | Case report | 1 | Atezolizumab + Bevacizumab | Complete clinical remission achieved; successful LT with no recurrence at 10-month follow-up |

| Kuo et al[17] | Case series | 4 | Atezolizumab, Nivolumab, Pembrolizumab | Safe washout period of 42 days recommended for LT following ICI therapy |

| Schnickel et al[18] | Case Series | 5 | Nivolumab | Pretransplant use of ICIs, particularly within 90 days of LT, was associated with biopsy-proven acute cellular rejection and immune-mediated hepaticnecrosis |

The time interval between the last dose of ICIs and LT is crucial for minimizing immune-related complications. Tabrizian et al[11] recommended a washout period of at least 30 days because their findings showed that patients receiving ICIs within this timeframe experienced no severe allograft rejection. Nordness et al[13] suggested that the half-life of nivolumab (approximately 25 days) necessitates careful consideration and proposed that ICIs should not be administered within six weeks before LT activation owing to the risk of prolonged immune effects. Aby and Lake reported successful LT with nivolumab cessation 16 days prior to the procedure but emphasized that individual risk factors and immune responses must guide the timing[15]. Kuo et al[17] conducted a study to optimize the washout period for ICIs, including atezolizumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab. They found that a washout period of at least four to six weeks was effective in minimizing postoperative complications and improving outcomes. This study supports the importance of individualized timing in balancing therapeutic benefits with safety.

The reviewed studies indicate promising survival outcomes for patients treated with ICIs before LT. Tabrizian et al[11] observed no deaths or tumor recurrences at a median follow-up of 16 months post-transplant, underscoring the potential of ICIs to improve long-term survival. Aby and Lake[15] reported that their patient remained well with normal liver function 16 months post-LT, suggesting that ICIs can contribute to favorable long-term outcomes when managed appropriately. Nordness et al[13] cautioned that the use of nivolumab can lead to fatal outcomes in some cases, high

The use of ICIs in a pre-transplant setting for HCC is associated with significant complications, primarily immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Chen et al[12] reported a case of fatal acute hepatic necrosis caused by toripalimab-induced immune rejection post-LT, highlighting the severe risks involved. Nordness et al[13] documented a fatal outcome following pre-transplant nivolumab use, reinforcing the need for extreme caution and careful patient selection. Tabrizian et al[11] noted that although there were no severe allograft rejections in their cohort, one patient experienced mild acute rejection, which was manageable with increased immunosuppression. Aby and Lake[15] reported early T cell–mediated rejection in a patient who was successfully treated with high-dose steroids and thymoglobulin, indicating that prompt management of complications can lead to positive outcomes. These studies collectively underscore the importance of vigilant monitoring and aggressive management of irAEs to mitigate the risks associated with ICI therapy in patients awaiting liver transplantation.

The selection of patients for ICI therapy before LT is critical for optimizing outcomes and minimizing risks. Tabrizian et al[11] emphasized the importance of identifying patients who could potentially benefit from ICIs without a significant risk of severe immune-related adverse events. They highlighted that patients initially outside the Milan criteria due to tumor burden or vascular invasion could still be eligible for LT following effective downstaging with ICIs. Chen et al[12] discussed the need for a thorough pretreatment evaluation to identify candidates who can tolerate ICIs and benefit from their tumor-reducing effects without experiencing severe complications.

Nordness et al[13] underscored the necessity of individualized patient assessment, including detailed evaluations of tumor characteristics, liver function, and overall health, to ensure that the benefits of ICI therapy outweigh the associated risks. Their findings suggested that patients with significant tumor burden but otherwise stable liver function could be ideal candidates for ICI therapy as a bridge to LT. Aby and Lake[15] highlighted that patients with complex HCC, such as those with malignant PVTT, could still be considered for ICI therapy if they demonstrated a good response to initial treatments and maintained overall health stability.

Overall, careful patient selection based on comprehensive clinical evaluations and stringent criteria is essential for maximizing the efficacy and safety of ICI therapy in pre-transplant settings. This approach helps identify patients most likely to benefit from ICIs while minimizing the risk of severe complications, thereby improving the overall outcomes for patients with advanced HCC awaiting LT.

This systematic review synthesizes data from eight key studies examining the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC prior to LT. The findings from these studies demonstrate the significant potential of ICIs, particularly when used in combination with agents such as bevacizumab, to effectively reduce tumor burden in patients with advanced HCC. This reduction in tumor size and extent has enabled patients who were previously deemed ineligible for LT because of extensive disease to become candidates for transplantation.

The inclusion of ICIs in pre-transplant treatment regimens represents a paradigm shift in the management of advanced HCC. Traditional downstaging methods, such as TACE and RFA, have shown limited success in patients with extensive disease. ICIs offer a novel therapeutic avenue that leverages the immune system to target and destroy cancer cells, thereby achieving significant tumor regression. The reviewed studies highlighted the transformative impact of ICIs on the treatment landscape of advanced HCC. For instance, Tabrizian et al[11 and Nordness et al[13] provided compelling evidence of tumor necrosis and successful downstaging, allowing subsequent LT without severe complications. Moreover, the studies underscore the importance of patient selection and the timing of therapy cessation to maximize benefits and minimize risks.

ICIs have demonstrated substantial efficacy in achieving meaningful tumor regression, thereby facilitating successful LT in patients with advanced HCC. This effectiveness is crucial, as it allows patients with extensive disease to become eligible for LT. For instance, Tabrizian et al[11] reported significant tumor necrosis with nivolumab, enabling LT without severe complications. Similarly, the combination of ICIs with agents such as bevacizumab has been shown to enhance these outcomes by leveraging both immune activation and anti-angiogenesis mechanisms, providing a dual attack on tumor growth and vascular support. The effectiveness of ICIs in downstaging HCC is a critical advancement in this field. ICIs such as nivolumab and toripalimab have shown significant tumor reduction, which is pivotal for enabling LT in patients who were previously deemed ineligible owing to extensive tumor burden. The combination of ICIs with be

Determining the optimal timing for LT post-ICI therapy is critical for minimizing the risk of irAEs. An appropriate washout period between the last dose of ICIs and LT can mitigate perioperative risks and ensure patient safety. The reviewed studies suggested varying washout periods; however, a personalized assessment based on patient-specific factors is crucial. Kuo et al[17] recommended a washout period of at least 30 days and observed no severe allograft rejection within this timeframe. In contrast, Nordness et al[13] suggested avoiding ICI use within six weeks before LT activation due to the prolonged immune effects of nivolumab. Fisher et al[19] emphasized the need for individualized timing based on patient-specific factors. These insights suggest that while general recommendations can be made, personalized assessment is crucial for determining the appropriate washout period. The timing between the last dose of ICIs and LT is essential to minimize immune-related complications. Ensuring an adequate washout period is vital for balancing the therapeutic benefits of ICIs with the safety requirements of LT. Studies have suggested washout periods ranging from 16 days to several weeks, with personalized assessments being crucial for determining the most appropriate interval for each patient[11,17].

ICIs have shown the potential to significantly improve long-term survival outcomes in patients treated before LT. By facilitating significant tumor regression and enabling LT, ICIs can extend survival rates in patients with advanced HCC who would otherwise have limited treatment options. Studies have reported no deaths or tumor recurrences at a median follow-up of 16 months post-transplantation, highlighting the potential of ICIs to enhance long-term survival[11]. This suggests that when used judiciously and with appropriate patient management, ICIs can significantly improve survival rates for patients with advanced HCC undergoing LT who would otherwise have limited treatment options. The potential of ICIs to improve long-term survival outcomes for patients treated before LT is promising. Studies have reported no deaths or tumor recurrences at a median follow-up of 16 months post-transplantation, highlighting the potential of ICIs to enhance long-term survival. These findings underscore the importance of careful patient selection and monitoring to balance the benefits and risks associated with their use.

Although ICIs offer significant benefits, they are associated with irAEs that require vigilant monitoring and mana

Effective patient selection is crucial to optimize the benefits and minimize the risks of ICI therapy before LT. Comprehensive clinical evaluations and stringent criteria are essential for identifying suitable candidates for this treatment approach. Studies have emphasized the importance of selecting patients who can benefit from ICIs without a significant risk of severe irAEs. Thorough pretreatment evaluations are necessary to ensure that patients can tolerate ICIs and benefit from tumor reduction without experiencing severe complications[12]. Overall, careful patient selection based on comprehensive evaluations is critical for maximizing the efficacy and safety minimizing the risks of ICI therapy in the pre-transplant setting. Comprehensive clinical evaluation and stringent criteria are necessary to identify suitable candidates for this treatment approach. Studies have emphasized the importance of thorough pre-treatment evaluations to ensure that patients can tolerate ICIs and benefit from tumor reduction without experiencing severe complications.

The potential use of ICIs in patients with HCC and PVTT is particularly noteworthy for downstaging advanced HCC for LT. Kumar et al[14] reported the first case of successful downstaging using a combination of atezolizumab and bevacizumab. This combination therapy resulted in significant tumor shrinkage, enabling the patient to qualify for LT. This case underscores the potential of combining ICIs with antiangiogenic agents to enhance downstaging outcomes. Additionally, Aby and Lake[15] highlighted that patients with complex HCC, including those with malignant PVTT, could still be considered for ICI therapy if they demonstrate a good response to initial treatments and maintain overall health stability. This evidence suggests that ICIs, particularly when used in combination with other therapeutic agents, provide a viable pathway for curative surgery in patients with advanced and complicated HCC. Soin et al[20] described comparable findings that provided a powerful testament to the curative effects of downstaging in the treatment of advanced HCC with PVTT. Based on a similar concept, Bhangui et al[21] also reported acceptable long-term results after LT in an intention-to-treat strategy for HCC with PVTT if good patient selection depending on tumor biology, imaging-based downstaging with decreased tumor marker levels, and a minimum waiting period with stable disease were achieved. Traditional downstaging methods have had limited success in such complex cases; however, the advent of ICIs, particularly in combination with agents such as bevacizumab, offers a novel therapeutic approach. This strategy not only targets the primary tumor but also addresses the vascular component, thereby enhancing the overall efficacy of the treatment and improving patient outcomes.

Recommendations for optimizing the use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC prior to LT are well established (Table 2). ICIs should be considered for patients with HCC requiring downstaging therapy before LT as well as for those with HCC complicated by PVTT who are potential candidates for transplantation. Contraindications include a history of severe autoimmune diseases that can be exacerbated by ICIs, ongoing significant infections, and decompensated liver disease where the risks outweigh the benefits. ICIs should be initiated as part of a structured pre-transplant downstaging protocol to reduce tumor size within transplant criteria and control disease progression in advanced HCC with PVTT. It is crucial to stop ICIs at least 4-6 weeks before the planned LT to reduce the risk of graft rejection and ensure the resolution of immune activation. Regular monitoring of liver function and immune response during ICI treatment, as well as close follow-up after cessation, is necessary to detect and manage late-onset immune-related adverse events and ensure patient readiness for transplantation. Post-LT, the implementation of standardized immunosuppressive regimens tailored to the patient's condition and prior ICI therapy, along with adaptive management of immunosuppression based on patient response, is recommended to optimize outcomes[22,23].

| Aspect | Recommendation |

| Indications | HCC: Patients requiring downstaging therapy before liver transplantation. PVTT: Patients with HCC complicated by PVTT who are candidates for liver transplantation |

| Contraindications | Autoimmune diseases: History of severe autoimmune diseases that could be exacerbated by ICIs. Infections: Ongoing significant infections that may be worsened by immunotherapy. Liver disease: Decompensated liver disease where the risks of ICIs outweigh potential benefits |

| Timing of ICI initiation | Pre-transplant downstaging: Start ICIs as part of a structured downstaging protocol for HCC to shrink tumors to within transplant criteria. Advanced HCC management: Initiate ICIs in patients with advanced HCC and PVTT to control disease progression pre-transplant |

| Timing of ICI cessation | Before liver transplantation: Stop ICIs at least 4-6 weeks prior to planned liver transplantation to reduce the risk of graft rejection. Immune resolution: Ensure resolution of immune activation and monitoring for potential adverse effects post-ICI cessation before proceeding to LT |

| Monitoring and follow-up | Regular assessment: Frequent monitoring of liver function and immune response during ICI treatment. Post-ICI cessation: Close follow-up after stopping ICIs to detect and manage any late-onset immune-related adverse events and ensure patient readiness for transplantation |

| Immunosuppressive strategy post-LT | Standardized protocols: Implement standardized immunosuppressive regimens tailored to the patient's condition and prior ICI therapy to prevent graft rejection. Adaptive management: Adjust immunosuppression based on patient response and any emerging complications post-transplant |

Despite these promising findings, several limitations should be addressed in future studies. The heterogeneity in study designs, patient populations, and treatment protocols complicates the ability to draw definitive conclusions. The small sample sizes of some studies, particularly case reports, limit the generalizability of the results. Future research should focus on large-scale prospective studies to validate the efficacy and safety of ICIs in pre-transplant settings. Establishing standardized protocols for ICI administration, washout periods, and post-transplant monitoring is crucial. Additionally, evaluating long-term outcomes, including recurrence rates, graft survival, and overall survival, will provide a comprehensive understanding of the benefits and risks associated with this therapeutic approach. Addressing these research gaps will help optimize the integration of ICIs into the treatment paradigm for advanced HCC, ultimately improving patient outcomes. Current knowledge gaps include a lack of standardized protocols for ICI administration and variability in study design. Researchers should focus on large-scale prospective studies to validate these findings and develop uniform guidelines for ICI use in the pre-transplant setting, thereby enhancing patient outcomes.

Future research should address the heterogeneity in study design, patient populations, and treatment protocols to draw more definitive conclusions. In the next five years, we anticipate significant advancements in the integration of ICIs into standard treatment protocols for advanced HCC. With ongoing large-scale studies, we are likely to see the development of standardized guidelines for ICI administration and post-transplant care. Additionally, improvements in patient selection criteria and personalized treatment approaches will enhance the safety and efficacy of ICIs, potentially making liver transplantation accessible to a broader range of patients with advanced HCC. This evolution could lead to improved long-term survival rates and reduced recurrence, firmly establishing ICIs as the cornerstone for the management of advanced HCC.

The use of ICIs for downstaging advanced HCC before LT represents a significant advancement in the management of this challenging disease. Evidence from the reviewed studies indicates that ICIs, particularly in combination with agents such as bevacizumab, can effectively reduce tumor burden. This therapeutic approach expands the pool of patients eligible for LT, offering new hope to those who were previously deemed ineligible because of extensive disease or advanced tumor characteristics. The ability to downstage tumors and facilitates LT opens up curative treatment possibilities for a broader patient population, potentially improving overall survival rates and quality of life.

However, while the potential benefits are substantial, careful consideration of the timing and management of ICI therapy is crucial for mitigating the associated risks. The timing of therapy cessation before LT is particularly important for minimizing the risk of irAEs during the perioperative period. Studies have suggested a washout period of at least four to six weeks between the last dose of ICI and LT to ensure that patients are in optimal condition for surgery. This interval allows for stabilization of the immune system and reduces the likelihood of perioperative complications.

The management of potential adverse effects also requires a multidisciplinary approach involving close monitoring and prompt intervention at the first sign of irAEs. Comprehensive pre-transplant evaluations and post-transplant care are essential to ensure patient safety and improve outcomes. As the field evolves, further research is essential to refine treatment protocols, establish standardized guidelines, and evaluate long-term outcomes, including recurrence rates, graft survival, and overall survival.

Future studies should focus on large-scale prospective trials to validate the efficacy and safety of ICIs in pre-transplant settings. Additionally, exploring the potential of combining ICIs with other therapeutic modalities and identifying biomarkers to predict responses to therapy could further enhance patient outcomes. By addressing these research gaps and continuously improving clinical practices, the integration of ICIs into the treatment paradigm for advanced HCC can be optimized, offering significant benefits to patients and advancing the fields of oncology and transplantation medicine.

| 1. | Yang JD, Hainaut P, Gores GJ, Amadou A, Plymoth A, Roberts LR. A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma: trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2184] [Cited by in RCA: 3113] [Article Influence: 444.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (17)] |

| 2. | Sahin TK, Rizzo A, Aksoy S, Guven DC. Prognostic Significance of the Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH) Score in Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mahipal A, Tella SH, Kommalapati A, Lim A, Kim R. Immunotherapy in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Is There a Light at the End of the Tunnel? Cancers (Basel). 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | O'Connor JK, Trotter J, Davis GL, Dempster J, Klintmalm GB, Goldstein RM. Long-term outcomes of stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of hepatocellular cancer as a bridge to transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:949-954. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Block PD, Strazzabosco M, Jaffe A. Approach to immunotherapy for HCC in the liver transplant population. Clin Liver Dis (Hoboken). 2024;23:e0158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kudo M. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Basics and Ongoing Clinical Trials. Oncology. 2017;92 Suppl 1:50-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shen KY, Zhu Y, Xie SZ, Qin LX. Immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment and immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and prospectives. J Hematol Oncol. 2024;17:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zeng Z, Yang B, Liao ZY. Current progress and prospect of immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2020;20:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hayakawa Y, Tsuchiya K, Kurosaki M, Yasui Y, Kaneko S, Tanaka Y, Ishido S, Inada K, Kirino S, Yamashita K, Nobusawa T, Matsumoto H, Kakegawa T, Higuchi M, Takaura K, Tanaka S, Maeyashiki C, Tamaki N, Nakanishi H, Itakura J, Takahashi Y, Asahina Y, Okamoto R, Izumi N. Early experience of atezolizumab plus bevacizumab therapy in Japanese patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in real-world practice. Invest New Drugs. 2022;40:392-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Giannini EG, Aglitti A, Borzio M, Gambato M, Guarino M, Iavarone M, Lai Q, Levi Sandri GB, Melandro F, Morisco F, Ponziani FR, Rendina M, Russo FP, Sacco R, Viganò M, Vitale A, Trevisani F; Associazione Italiana per lo Studio del Fegato (AISF) HCC Special Interest Group. Overview of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy for Hepatocellular Carcinoma, and The ITA.LI.CA Cohort Derived Estimate of Amenability Rate to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Clinical Practice. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tabrizian P, Florman SS, Schwartz ME. PD-1 inhibitor as bridge therapy to liver transplantation? Am J Transplant. 2021;21:1979-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Chen GH, Wang GB, Huang F, Qin R, Yu XJ, Wu RL, Hou LJ, Ye ZH, Zhang XH, Zhao HC. Pretransplant use of toripalimab for hepatocellular carcinoma resulting in fatal acute hepatic necrosis in the immediate postoperative period. Transpl Immunol. 2021;66:101386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nordness MF, Hamel S, Godfrey CM, Shi C, Johnson DB, Goff LW, O'Dell H, Perri RE, Alexopoulos SP. Fatal hepatic necrosis after nivolumab as a bridge to liver transplant for HCC: Are checkpoint inhibitors safe for the pretransplant patient? Am J Transplant. 2020;20:879-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kumar P, Krishna P, Nidoni R, Adarsh CK, Arun MG, Shetty A, Mathangi J, Sandhya, Gopasetty M, Venugopal B. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab as a downstaging therapy for liver transplantation in hepatocellular carcinoma with portal vein thrombosis: The first report. Am J Transplant. 2024;24:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Aby ES, Lake JR. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy Before Liver Transplantation-Case and Literature Review. Transplant Direct. 2022;8:e1304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chouik Y, Erard D, Demian H, Schulz T, Mazard T, Hartig-Lavie K, Antonini T, Mabrut JY, Mohkam K, Rode A, Merle P. Case Report: Successful liver transplantation after achieving complete clinical remission of advanced HCC with Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab combination therapy. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1205997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kuo FC, Chen CY, Lin NC, Liu C, Hsia CY, Loong CC. Optimizing the Safe Washout Period for Liver Transplantation Following Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors with Atezolizumab, Nivolumab, or Pembrolizumab. Transplant Proc. 2023;55:878-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schnickel GT, Fabbri K, Hosseini M, Misel M, Berumen J, Parekh J, Mekeel K, Dehghan Y, Kono Y, Ajmera V. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma following checkpoint inhibitor therapy with nivolumab. Am J Transplant. 2022;22:1699-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fisher J, Zeitouni N, Fan W, Samie FH. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in solid organ transplant recipients: A patient-centered systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1490-1500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Soin AS, Bhangui P, Kataria T, Baijal SS, Piplani T, Gautam D, Choudhary NS, Thiagarajan S, Rastogi A, Saraf N, Saigal S. Experience With LDLT in Patients With Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Portal Vein Tumor Thrombosis Postdownstaging. Transplantation. 2020;104:2334-2345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bhangui P. Liver transplantation and resection in patients with hepatocellular cancer and portal vein tumor thrombosis: Feasible and effective? Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2024;23:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Li Z, Zhai Y, Wu F, Cao D, Ye F, Song Y, Wang S, Liu Y, Song Y, Tang Y, Jing H, Fang H, Qi S, Lu N, Li YX, Wu J, Chen B. Radiotherapy with Targeted Therapy or Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Hepatocellular Carcinoma with Hepatic Vein and/or Inferior Vena Cava Tumor Thrombi. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2024;11:1481-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fu Y, Guo X, Sun L, Cui T, Wu C, Wang J, Liu Y, Liu L. Exploring the role of the immune microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: Implications for immunotherapy and drug resistance. Elife. 2024;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/