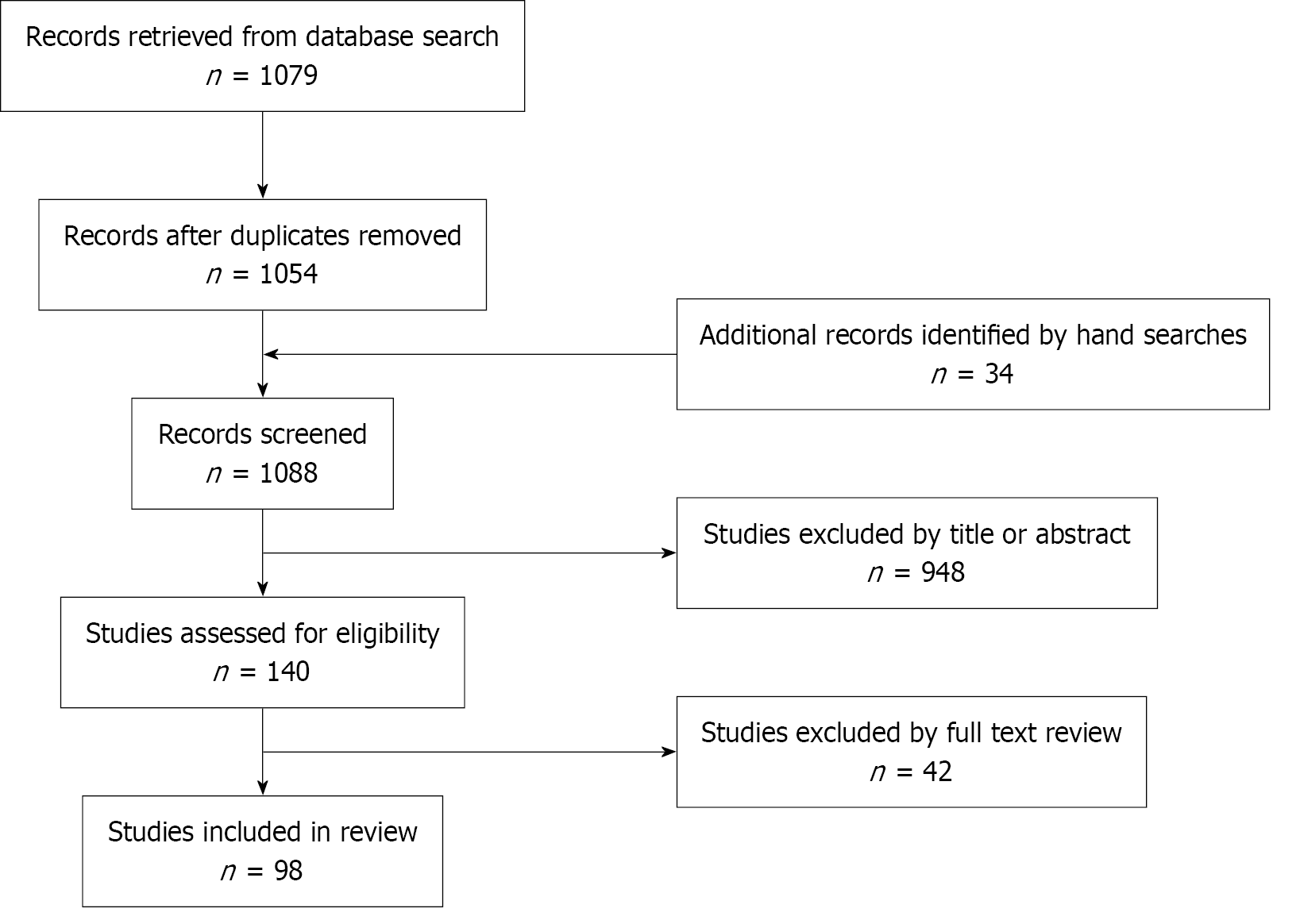

RESULTS

Carbohydrate metabolism

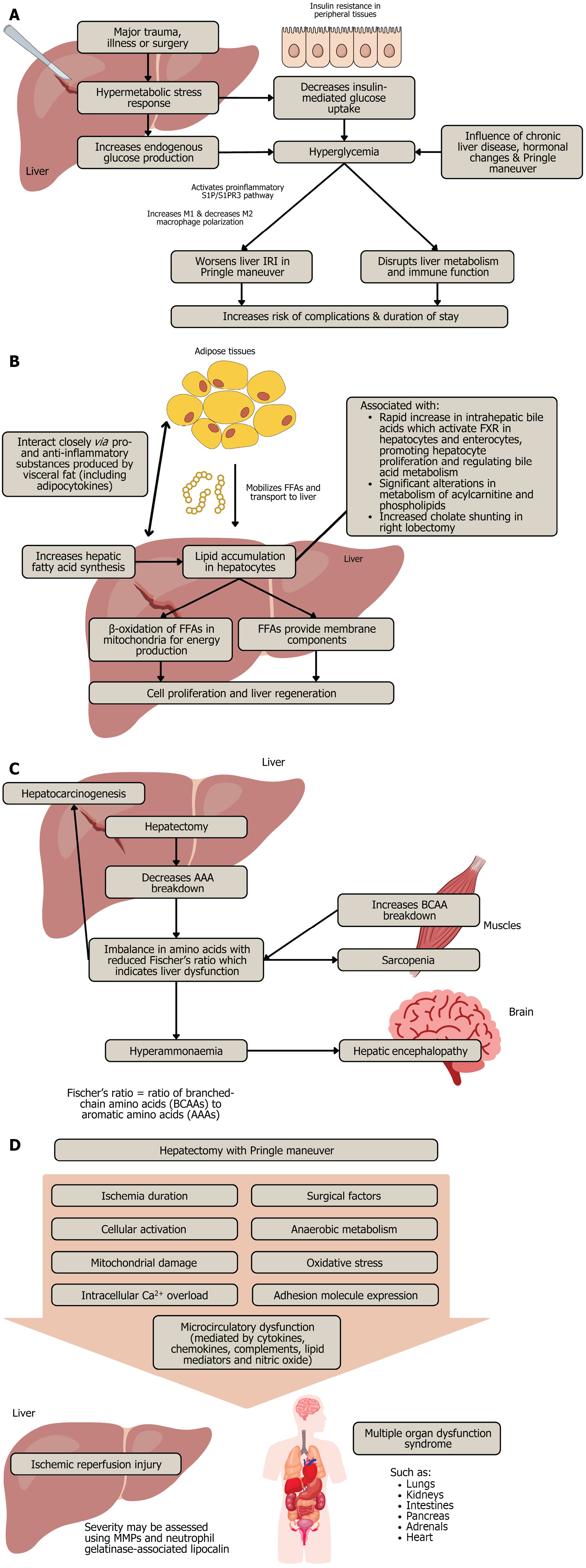

Liver makes and breaks carbohydrates, hence hepatectomy is associated with alterations in glucose homeostasis. The surgical stress following hepatectomy commonly leads to a transient hyperglycaemia with serum glucose levels remaining elevated for up to 16 hours[5]. Major trauma, illness or surgery often activates a hypermetabolic stress response characterised by elevated endogenous glucose production in the liver and decreased insulin-mediated glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, resulting in hyperglycaemia and insulin resistance (Figure 2A)[9]. Chronic liver disease or fibrosis, hormonal changes (such as changes in insulin, cortisol, glucagon and noradrenaline) and the Pringle manoeuvre influence post-hepatectomy hyperglycaemia, which serves as an indicator of glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis[5].

Figure 2 Mechanisms and effects following hepatic resection.

A: Hyperglycaemia; B: Hepatic lipid accumulation; C: Hepatic lipid accumulation; D: Ischaemic-reperfusion injury. IRI: Ischaemic reperfusion injury; FFA: Free fatty acids; AAA: Aromatic amino acids; BCAA: Branched-chain amino acids; FXR: Farnesoid X receptor; MMP: Matrix metalloproteinases.

This elevation, especially if severe (glucose > 200 mg/dL), disrupts liver metabolism and immune function, thereby increasing the risk of postoperative complications, especially infection, and increasing the duration of stay[5,9]. When the Pringle manoeuvre is performed, hyperglycaemia worsens liver ischaemic reperfusion injury (IRI) by activating sphingosine-1-phosphate and sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 3 signalling, and promoting M1 macrophage polarisation while supressing M2 macrophage polarisation, hence targeting this pathway could serve as a potential therapeutic approach for managing liver IRI in hyperglycaemia[10,11]. In patients with colorectal liver metastases, early postoperative hyperglycaemia was associated with increased risk of overall complications and poor outcomes, regardless of diabetes mellitus (DM) status, highlighting the potential importance of perioperative glucose monitoring as quality care target[9].

On the other hand, aggressively treating severe hyperglycaemia in critically ill patients can heighten the risk of serious hypoglycaemia-related complications, leading to increased mortality among adults in the intensive care unit when intensive glucose control is applied[9]. In patients undergoing major liver resection, perioperative glucose and insulin administration while maintaining normoglycemia effectively achieves normoglycemia after surgery by reducing the standard deviation and coefficient of variability of blood glucose, especially in non-diabetic patients.

DM causes vasculopathy, thus it is impairs liver regeneration and directly impacts short-term outcomes after major hepatectomy, with a higher risk of bile leakage, liver failure, Clavien-Dindo grade IV complications, overall morbidity and unplanned readmissions, though it does not increase mortality[12,13]. Hence, identifying high-risk patients preoperatively can help reduce complications and facilitate patient-tailored counselling within a shared decision-making framework. In contrast, major hepatectomy is safe for obese and overweight patients, whose postoperative outcomes are comparable to those of individuals with normal weight. Moreover, DM is also associated with intrahepatic hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) recurrence, overall relapses and reduced local control, including patients with hepatitis B-related HCC, hence more focus should be directed toward the care and management of patients with HCC and DM[14].

In hepatitis B-associated HCC patients post-hepatectomy, the presence of metabolic syndrome increases the risk of postoperative complications, especially post-hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF), hydrothorax and hyperglycaemia, and worsens overall survival and recurrence-free survival, highlighting the need for greater vigilance in addressing metabolic disorders in tumour patients[15].

The utilisation of robot-assisted laparoscopy in patients with synchronous colorectal liver metastases significantly reduced serum cortisol, norepinephrine and glucose levels 3 days after hepatectomy, hence potentially enhancing perioperative outcomes, alleviating stress and lowering the risk of complications[16]. However, as existing literature presents mixed findings, with some studies showing no significant difference or even favouring conventional laparoscopy, further research is needed to confirm the reproducibility and generalisability of these results[17,18].

Lipid metabolism

Liver makes and breaks lipids. After partial hepatectomy, systemic adipose tissue mobilises free fatty acids (FFAs) which are transported to the liver, and hepatic fatty acid synthesis may also increase transiently during regeneration, though the liver primarily relies on external lipid sources from adipose tissue[19]. Hence, hepatocytes accumulate lipids during the early stages of liver regeneration, and this transient steatosis is thought to provide critical substrates for β-oxidation and energy production, as well as membrane components necessary for cell proliferation and liver regeneration[19-21] (Figure 2B). The transient hepatic steatosis is essential and blocking fat accumulation impairs regeneration. β-oxidation of FFAs in mitochondria is vital during regeneration and impaired β-oxidation can delay or impair liver regeneration. Moreover, metabolic disturbances, such as lipid mobilisation, following liver injury act as primary signals that initiate hepatocyte proliferation[21].

The non-protein respiratory quotient (npRQ) measures the ratio of fat to carbohydrate oxidation and can be used to evaluate energy malnutrition through indirect calorimetry[22]. Following hepatectomy, one way to assess hepatic functional reserve is through the indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes (ICGR15), where a lower ICGR15 indicates better liver function and clearance capacity. Postoperative assessments reveal that npRQ significantly decreased in patients undergoing either minor or major resections with low ICGR15, while non-esterified fatty acid levels significantly increased on postoperative day 4 in those undergoing major resections with low ICGR15[23]. Single and multiple regression analyses showed a significant correlation between changes in npRQ and resection volume, after accounting for age, aetiology and ICGR15 in multiple regression, indicating that postoperative nutritional recovery is slower in patients undergoing major compared to minor resections, hence highlighting the need for nutritional support to prevent starvation in major resection cases[23].

Intrahepatic bile acids rapidly increase after liver resection, and they play a key role in liver regeneration by activating the farnesoid X receptor (FXR) in hepatocytes, hence promoting cell proliferation and regulating bile acid metabolism[24]. Furthermore, FXR activation in enterocytes induces fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), which enters the portal circulation and binds to FGFR4 on hepatocytes, further supporting liver regeneration and regulating bile acid production[24]. This FXR-FGF19-FGFR4 pathway is crucial for maintaining liver function, and its therapeutic potential is being explored to enhance liver regeneration and prevent liver failure in patients undergoing major liver resection or injury. In liver regeneration in living liver donors, significant alterations were observed in the levels of 15 primary and secondary plasma bile acids, with the most notable changes occurring 2 days after major hepatectomy and lasting for up to 3 months, as well as in the metabolism of acylcarnitine and phospholipids[25]. Additionally, following right hepatic lobectomy in living donors for liver transplantation, the portal circulation was significantly altered through increased cholate shunting (which is a reduction in clearance of orally administered cholate compared to intravenously administered cholate), spleen enlargement and reduced platelet count, with the rapid early phase of hepatic regeneration contributing to nearly two-thirds of the total regeneration and associated with increased hepatic blood flow and cholate uptake (Figure 2B)[26].

Adipose tissue and the liver interact closely, as pro- and anti-inflammatory substances from visceral fat reach the liver directly via the portal vein, hence adipose tissue has been linked to both harmful and protective effects on liver injury and the regenerative process following liver surgery[27]. Adipocytokines influence steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis, and are widely found in liver resections, thus holding promise as biomarkers for assessing the severity of steatosis and liver damage, though pharmacological regulation of adipocytokines has not yet shown clinical benefits[28].

Chronic fatty liver disease is associated with reduced regenerative capacity, and the degree of steatosis correlates with the extent of impairment, involving mechanisms such as lipid-induced oxidative stress, inflammation and disrupted regenerative signalling pathways[29]. Hepatic steatosis causes alterations in the haemodynamics of liver sinusoids, which increases the likelihood of IRI and elevates the risk of postoperative complications[29]. Patients with any degree of steatosis undergoing hepatectomy for neoplasm face twice the risk of postoperative complications and those with severe steatosis (greater than 30%) have nearly 3 times the risk of death[19]. In cases of liver resection for living related liver donation, patients with mild steatosis exhibit slower liver volume recovery in the first 3 months post-surgery, and reduced liver function recovery 6 to 12 months after the procedure[19]. A study by the Banff Working Group on Liver Allograft Pathology revealed significant variation among pathologists in assessing steatosis in donor liver biopsies, leading to the development of proposed guidelines for standardization, which include defining "large droplet fat" and establishing an algorithmic approach for assessing fat droplet size and hepatocyte involvement, with the intent to improve liver transplantation outcomes[30].

Protein metabolism

Liver makes and breaks proteins, hence hepatectomy leads to imbalances in amino acids, which can result in hyperammonaemia and contribute to hepatic encephalopathy[5]. The liver is crucial for amino acid metabolism, detoxification of ammonia, and maintaining the balance between branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) and aromatic amino acids (AAAs), measured by Fischer’s ratio[5,31]. A reduced Fischer’s ratio, due to increased BCAA catabolism in muscle and decreased AAA breakdown in the liver, indicates liver dysfunction, and is thought to cause hepatic encephalopathy, sarcopenia and hepatocarcinogenesis (Figure 2C). The Pringle manoeuvre affects individual amino acid levels but not the Fischer’s ratio, though there is an inverse correlation between plasma AAA levels and remnant liver volume after hepatectomy. Additionally, the ratio of BCAAs to tyrosine correlates with liver function and jaundice duration post-surgery[5].

In liver regeneration in living liver donors, amino acid metabolism was significantly altered, affecting the sum of AAA and the Fischer’s ratio, both indicators of liver damage, and the symmetrically demethylated arginine-to-arginine ratio, a marker of kidney function[25]. Moreover, after major hepatectomy in children, serum protein levels remained low and did not return to their preoperative levels[32]. These changes in amino acid flux, particularly increased levels of BCAAs and alterations in methionine metabolism, are associated with liver regeneration[21].

A protein and metabolite profile has been identified in the serum of living liver donors that reflects key cellular processes during liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy, highlighting biomarkers such as IGFALS, PHB1, 1433Z, bile acids, serine, and glycine, which could help monitor liver regeneration and prevent complications following hepatectomy[33]. The increase in PHB1 could serve as a potential indicator of mitochondrial activation and effective liver regeneration, while the downregulation of one-carbon metabolism enzymes during the early phase of liver regeneration may support hepatocyte growth[33]. Metabolic reprogramming driven by insulin signalling supports energy production and hepatocyte proliferation, with mitochondrial activation mediated by PHB1 playing a central role. Moreover, the lack of activation of MAT2A and B suggests controlled cell proliferation during liver regeneration[33]. Augmenter of liver regeneration (ALR) is a protein encoded by the GFER gene that specifically supports liver regeneration and responds to various regulatory factors[34]. ALR exists in three isoforms with distinct functions: The long forms are found in the inner mitochondrial space (IMS) and cytosol, while the mitochondrial ALR interacts with Mia40 to ensure proper protein folding during IMS import, and the short form is primarily located in the cytosol and has anti-apoptotic, anti-oxidative, anti-inflammatory and metabolic regulatory functions[34]. Moreover, hepatocyte growth factor has also been found to have a positive correlation with liver regeneration[35].

Following adult living donor liver transplant, recipients experienced a rapid recovery of the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) axis, while donors exhibited altered GH signalling during the early postoperative days[36]. In recipients, GH serum levels decreased, while donors showed an increase in GH to normal levels in the early postoperative period[36]. Recipients’ IGF1 serum levels returned to normal within the first postoperative week, whereas donor IGF1 levels dropped by 50% after donation and returned to preoperative levels after 6 months[36]. Glucagon-like peptide-1 and 2 (GLP-1 and 2) exhibit dynamic, inversely regulated patterns during liver regeneration, likely driven by changes in expression or release rather than degradation capacity[37]. These shifts are more pronounced in cases of PHLF and significant declines in plasma lipid levels also correlate with GLP-2 dynamics. Following hepatectomy, plasma ghrelin levels dropped significantly on day 1 but returned to preoperative levels by day 3, and this temporary decrease and quick normalisation was unaffected by the type of surgical procedures or their invasiveness[38].

Oxygen and energy consumption

Liver makes and breaks lactic acid. In surgery, tissue oxygen debt is reflected by inadequate oxygen consumption (VO2) in the intraoperative and immediate postoperative periods, and tissue VO2 deficit can be calculated as the measured VO2 minus the estimated VO2 requirements corrected for both temperature and anaesthesia[39,40]. In high risk surgical patients, a greater and prolonged VO2 deficit is strongly linked to multiple organ failure, complications, and death[39,40]. Preventing or minimizing oxygen debt by enhancing oxygen delivery can improve outcomes, and ideally, oxygen debt should be repaid within 24 hours post-surgery, as persistent high lactate levels predict increased morbidity[39]. High End-Surgery Arterial Lactate Concentration (ES-ALC) of > 5.0 mmol/L predicts severe complications post-hepatectomy, and these patients had longer surgery and ischaemia duration, more blood losses and greater requirements of fluids and transfusions[41]. It was found that surgery duration and the lowest recorded oxygen delivery value were the strongest predictors of high ES-ALC, and timely correction of blood losses might prevent the ES-ALC increase[41].

In cirrhotic patients undergoing hepatectomy, perioperative use of low-dose vasoactive drugs, particularly dobutamine, preserved immediate liver function postoperatively by maintaining total hepatic blood flow and compliance and enhancing hepatic oxygen supply and uptake[42]. Notably, lactate uptake fell in patients receiving dopamine and saline, but dobutamine recipients retained a positive lactate extraction capacity[42]. Additionally, in patients undergoing liver cancer surgery, the combination of dexmedetomidine and desflurane anaesthesia can reduce anaesthesia recovery time, enhance anaesthesia depth, and decrease cerebral oxygen metabolism without impacting cerebral function, demonstrating good safety[43]. However, desflurane has a high carbon footprint, with a 100-year global warming potential (GWP100) of 2540, where GWP100 is defined as the amount of atmospheric energy the emissions of one tonne of a particular gas will absorb over 100 years, relative to that of one tonne of carbon dioxide, meaning that the same mass of desflurane will warm the atmosphere approximately 2540 times more than CO2[44].

Low haemoglobin level of < 10.16 g/dL was identified as an independent risk factor for postoperative delirium following hepatectomy[45]. Plathypnoea orthodeoxia syndrome (POS) is a rare condition marked by dyspnoea and arterial oxygen desaturation in an upright position, which improve when lying down, and post-hepatectomy POS is an uncommon but serious complication, often requiring both an atrial communication and an anatomical alteration, such as a shift in the position between the vena cava ostium and interatrial septum[46].

IRI during liver resection with Pringle manoeuvre is influenced by ischaemia duration and surgical factors, and involves cellular activation, anaerobic metabolism, mitochondrial damage, oxidative stress, intracellular calcium overload, adhesion molecule expression, and microcirculatory dysfunction mediated by cytokines, chemokines, complements, lipid mediators and nitric oxide (Figure 2D)[5,47,48]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are a major cause of microvascular and tissue damage in IRI as mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation is inhibited during IRI, and oxidative respiratory chain damage leads to ATP depletion and excessive ROS production[49,50]. Mitochondrial dysfunction plays a key role in IRI, as excessive free radicals damage mitochondrial structure, function, and energy metabolism, as well as cause disruptions in mitochondrial fusion and fission which reduce the number of mitochondria, limiting the ability to clear ROS[50]. Mitochondrial membrane permeable transport pores form, resulting in cell necrosis, apoptosis, organ failure, and metabolic dysfunction, which contribute to increased morbidity and mortality[50]. Importantly, the glycocalyx (GCX), a protective mesh covering the endothelial surface, is particularly vulnerable to oxidative damage by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, which can then worsen IRI by causing vasoconstriction, promoting white blood cell adhesion, and activating immune cells[49]. During major liver surgery, GCX in hepatic sinusoids has been shown to be degraded by three ROS (hydroxyl radicals, carbonate radical anions, and hypochlorous acid), and heparanase also contributes to GCX degradation by cleaving it at the endothelial surface[49].

During liver injury caused by ischaemia, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) play a significant role in early leukocyte recruitment and may serve as therapeutic targets (Figure 2D)[48]. MMPs and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin are also potential markers for assessing the severity of IRI. The role of inflammasome-mediated inflammation in IRI has also been described, which might be a potential therapeutic target to alleviate IRI following hepatectomy[51]. Additionally, during liver ischaemia, lipoxygenase is excessively expressed, leading to lipid metabolic disorders[52]. During liver reperfusion, this overexpression triggers the release of proinflammatory cytokines, and lipid peroxidation by lipoxygenase also generates lipid oxygen free radicals, which contribute to iron-mediated cell death, apoptosis and tissue damage[52]. Moreover, intestinal venous congestion from portal triad clamping exacerbates IRI by promoting inflammatory mediators, thus impairing liver function and regeneration[5].

Hepatic IRI not only plays a central role in post-reperfusion damage of the liver itself, but also has widespread effects, contributing to dysfunction and injury in other organs such as the lungs, kidneys, intestines, pancreas, adrenals and heart, partly due to oxidative stress and the inflammatory response triggered by reperfusion[48,53]. The molecular and clinical manifestations of these injuries can lead to multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, commonly seen following liver surgery (Figure 2D). IRI induces shortening and deciliation of kidney primary cilia into the urine due to ROS and oxidative stress, suggesting that primary cilia are involved in IRI-induced acute kidney injury, and that the presence of ciliary proteins in urine could serve as a potential marker for kidney damage[54]. Hepatic IRI is classified into warm IRI, which is caused by liver surgery and systemic ischaemia, and cold IRI, which occurs during liver transplantation[55]. IRI is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, and it also increases the risk of tumour growth and recurrence following oncologic surgery for primary and secondary hepatobiliary cancers[47].

Diseased livers are more vulnerable to IRI and should not tolerate more than 60 minutes of warm ischaemia, with intermittent portal triad occlusion offering better protection against IRI[5]. For instance, IRI is more severe in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), where fat-laden hepatocytes are damaged by chronic oxidative and nitrosative stress, resulting in reduced antioxidant capacity and ATP depletion[56]. ONS is then exacerbated during IRI, leading to significant liver damage. Ischaemic preconditioning (IPC) enhances liver protection against IRI by modulating inflammatory and stress responses, preserving ATP, and improving blood flow through mechanisms like nitric oxide regulation and vasodilation, and can be done via surgical methods such as intermittent clamping. Additionally, administering N-acetylcysteine prior to liver IRI can help enhance IPC and reduce liver damage by lowering transaminase levels, enhancing bile production, and improving overall hepatic function[57]. In patients with HCC undergoing hepatectomy with vascular exclusion, IPC helps prevent IRI and protect liver function as indicated by postoperative transaminase levels, likely attributed to the reduction of sinusoidal epithelial cell apoptosis via downregulation of hepatic Fas mRNA expression and caspase-3 activity[58,59]. However, IPC was shown not to significantly improve outcomes in procedures like orthotopic liver transplantation or liver resection and current clinical evidence does not justify the routine application of IPC in liver surgery[60]. Additionally, IPC and anaesthetic preconditioning were found not to enhance cytoprotection from IRI when intermittent clamping is utilized[61].

In terms of reducing the risk for IRI, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is an energy-sensitive enzyme that regulates metabolic homeostasis[62]. During IRI, ischaemia causes a drop in ATP levels and a rise in the AMP/ATP ratio, which together with increased intracellular Ca2+ and the overproduction of ROS, triggers AMPK activation[62]. AMPK activation may offer protective effects by preserving energy levels, reducing inflammation, preventing hepatocyte apoptosis, and mitigating oxidative stress, hence AMPK could be a potential target for therapeutic interventions in IRI[62]. Moreover, studies have demonstrated that melatonin functions as an endogenous free radical scavenger with antioxidant properties and can alleviate hepatic IRI through its anti-inflammatory and anti-apoptotic effects[55]. Additionally, IRI creates an acidic microenvironment that suppresses the production and function of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ inducible regulatory T cells (iTregs) through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signalling pathway, however neutralising this acidity restores iTreg activity, enabling them to mitigate IRI[63]. Other effective antioxidant therapies with protective effects include hepatoprotective agents, attenuation of the increase in xanthine oxidase activity, and administration of antioxidants like N-acetylcysteine, superoxide dismutase and ornithine.

The liver faces increased energy demands for regeneration and there is reduced hepatic function due to ATP depletion[5]. In a normal liver, energy metabolism adapts to accommodate the increased metabolic load, though a decline in energy levels and reduction in normal functions occurs around postoperative day 4, coinciding with peak regenerative activity. In cirrhotic livers, this recovery is slower, likely due to limited adaptability in managing energy demands after hepatectomy[5]. The disruption in energy metabolism associated with liver regeneration is evidenced by a reduced ATP-to-inorganic phosphate ratio, and this energy depletion corresponds with impaired liver function tests, with recovery aligning with the restoration of liver cell mass. Post-hepatectomy metabolic changes are dependent on the extent of tissue injury and the quantity of remaining functional liver cells[64,65].

As liver regeneration is a high energy-dependent sequence of events, it is influenced by the energy status of hepatocytes[66]. Hence, as the primary energy producers and regulators of cell death, mitochondria play a crucial role in the liver’s response to hepatectomy, and mitochondrial dysfunction is linked to PHLF[66]. Post-hepatectomy, a reduction in detoxification capacity and hepatocyte energy supply in the residual liver tissue was observed, with a metabolic shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, leading to cellular hypoxia and elevated levels of lactate and superoxide radicals[67]. Therefore, there is a definitive role of boosting the energetic status of the liver in improving outcomes in hepatectomy[66].

After hepatectomy, resting energy expenditure increases, with a median rise of 11% and factors associated with a rise of > 11% being age and length of operation[68]. However, it was found that the use of robot-assisted laparoscopy in hepatectomy for colorectal cancer with liver metastases reduced the resting energy expenditure in postoperative days 1 to 3[16]. The liver's response and risk of failure after resection are heavily influenced by metabolic load and sensitivity to cell death, which are likely patient-specific, hence tailoring interventions to address these perioperative factors could support optimal liver regeneration and recovery[69].

DISCUSSION

This review highlights the intricate metabolic changes that occur following hepatectomy, encompassing changes in carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism, alongside alterations in oxygen and energy dynamics. This underscores the liver's central role in maintaining homeostasis during recovery, and aligns with the liver's pivotal role in systemic regulation and its remarkable regenerative capacity. The interplay of these metabolic pathways reveals significant implications for optimising perioperative care and improving long term outcomes, particularly in patients with underlying liver conditions or metabolic comorbidities. The findings presented here emphasise the multifaceted nature of metabolic changes post-hepatectomy, which are influenced by patient-specific factors.

The metabolic response to hepatic insufficiency serves as both a trigger and modulator of hepatocyte proliferation, and molecular mediators linking metabolism to regeneration include nuclear receptors (such as PPARα and FXR) which are implicated in sensing metabolic changes and driving hepatocellular proliferation, as well as growth factors (such as EGF) and intracellular signalling pathways (such as mTORC and AMPK) which play a role in integrating metabolic cues with cell cycle regulation[21]. Conditions like fatty liver disease, ageing, and acute liver failure can impair liver regeneration by disrupting metabolic homeostasis. A better understanding of metabolic regulation may lead to therapeutic strategies, including nutritional interventions and metabolomic biomarkers, to enhance liver regeneration in clinical settings[21].

The identification of predictive biomarkers and the advancements in perioperative care, including tailored nutritional support, glucose and lipid management, strategies to mitigate IRI, and emerging technologies such as robotic surgery and metabolic monitoring, have demonstrated potential in optimising recovery and minimising complications. However, the variability in patient responses highlights the need for personalised approaches and tailored therapeutic strategies to enhance liver regeneration and postoperative outcomes.

Post-hepatectomy complications

Refractory ascites is a significant complication following hepatectomy in cirrhotic patients with HCC, hence surgeons aim to preserve as much liver parenchyma as possible during the procedure to minimise this risk, though refractory ascites can still occur even after minor hepatectomy[70]. In cirrhotic patients with HCC undergoing minor hepatectomy (defined as hepatectomy involving a sub-segmentectomy or less), univariate analyses identified total cholesterol levels, operation duration, Pringle manoeuvre duration, resection of segment VII, intraoperative blood loss and intraoperative blood transfusion as significant risk factors for postoperative refractory ascites[70].

A major risk of liver surgery is PHLF, particularly in patients with HCC and cirrhosis, and risk factors include hepatitis B virus DNA levels, ICGR15, total bilirubin, prothrombin time, cirrhosis severity scoring, and intraoperative direct liver stiffness measurement[71]. In order to mitigate PHLF risk and improve patient outcomes, considerations include patient selection via liver function and tumour size, early risk prediction and longer term follow up[71]. Patients with PHLF showed increased intrahepatic and circulating HMGB1 levels, which were associated with markers of liver injury and cell death, such as K18 and ccK18, and these correlated with patient outcomes in PHLF[72]. Additionally, valine, alanine, and glycerophosphocholine have been identified as key biomarkers for predicting fatal PHLF, concluding that metabolomics proves valuable in predicting PHLF[73]. A longitudinal proteomic study of extracellular vesicles in the plasma of patients undergoing partial hepatectomy revealed proteomic signatures associated with PHLF, which indicate major disruptions in protein translation, proteostasis, intracellular vesicle formation, extracellular matrix remodelling, and metabolic and cell cycle pathways[74]. These changes suggest hepatocyte and endothelial cell damage, and were already present preoperatively, highlighting potential early markers of liver dysfunction[74].

To reduce the risk of IRI, strategies, such as high concentration intravenous glucose pre-surgery to boost hepatic glycogen and ATP content, have shown promise[5]. In liver resection, perioperative steroids administration may also reduce overall postoperative complications, bilirubin, and inflammation[75]. Additionally, normothermic machine perfusion of livers mimics physiologic liver function by using a red blood cell-based solution at 35.5 °C-37.5 °C, thereby reducing hyperfibrinolysis and inflammation, repleting glycogen and ATP, as well as protecting against IRI and hence early allograft dysfunction and biliary complications[76].

In terms of predicting HCC recurrence, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 was identified as a significant biomarker for predicting HCC recurrence, especially when combined with the pre-S2 gene deletion mutation[77]. Furthermore, the downregulation of caudal-type homeobox 1 transcription factor is associated with poor prognosis for HCC patients after hepatectomy, including a higher frequency of early recurrence and poorer overall survival[78]. While the concentration of intra-platelet VWF-Ag increases after hepatectomy, there is a dual effect of intra-platelet VWF on oncological outcome, as low preoperative VWF is linked to a higher risk of post-resection liver dysfunction, while elevated post-resection VWF-Ag is associated with early HCC recurrence[79].

After hepatectomy, alpha fetoprotein (AFP) levels > 500 ng/mL are associated with intrahepatic recurrence and overall relapses[14], and AFP level > 400 ng/mL is significantly correlated with poor overall survival[80-82]. Additionally, preoperative AFP level ≥ 20 ng/mL and preoperative serum protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II level ≥ 200 mAU/mL were significant predictors of disease-free survival[83,84]. Serum albumin is part of the cachexia index, which has also been proven to be a prognostic indicator in HCC patients after hepatectomy. Moreover, heat shock proteins, a group of stress-inducible proteins that help maintain cellular homeostasis and regulate the immune system, are pivotal in liver regeneration, acting as key markers of IRI and significantly impacting liver function[85].

Patients with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD face an elevated risk of postoperative complications and mortality following partial liver resection[86]. These adverse outcomes appear to stem from liver-specific complications as well as the increased cardiovascular sensitivity associated with metabolic syndrome and NAFLD. Additionally, NAFLD may specifically influence the recurrence of colorectal liver metastases[86].

Pringle manoeuvre

The Pringle manoeuvre is a surgical technique that involves the mechanical occlusion of blood flow to the liver by clamping the hepatobiliary structures, effectively reducing both portal and hepatic arterial blood inflow. This technique can be performed routinely or selectively, either proactively to minimize blood loss or reactively in response to excessive bleeding[87]. While abundant literature discusses the utility, benefits and drawbacks of the Pringle manoeuvre, as well as its physiological implications and clinical relevance, the scientific community has not yet fully recognized that this manoeuvre can be achieved without mechanical clamping. A physiological or functional approach entails pharmacological interventions, such as the use of somatostatin analogues, to reduce portal pressure. These interventions may offer similar benefits in minimizing blood loss while exerting less metabolic stress due to the preservation of arterial flow and circulation. Further strategies, including volume reduction through diuretics and the use of vasodilators like glyceryl trinitrate infusion, can help reduce total circulatory volume, thereby indirectly lowering portal pressure. Such approaches could serve as effective alternatives in achieving the physiological effects of the Pringle manoeuvre.

Understanding these alternatives is crucial for improving clinical outcomes following liver resection, which remains the cornerstone of curative management for patients with HCC. While oncological outcomes from liver transplantation are often regarded as superior to those from resection, the limited availability of donor organs, along with health economics and bioethical considerations, do not support the liberal use of liver transplants[88]. Just as one would repair a damaged car rather than replace it entirely, the same logic should apply in surgical decisions regarding liver cancer management.

Nutrition and prehabilitation

In terms of the effect of nutrition on liver regeneration, providing carbohydrates alone hinders liver recovery, instead, liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy and the repair of toxic liver damage can be significantly improved with lipid emulsion (Intralipid) infusion[89]. Lipid emulsions containing ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (ω-3 PUFAs) are a safe and effective option for controlling inflammation and preserving liver function in patients following hepatectomy, leading to fewer overall complications and shorter hospital stays[90]. While long-term intake of ω-3 PUFAs positively impacts metabolism and hepatic recovery, many patients require prompt surgical intervention, making extended n3-PUFA supplementation impractical, and poor adherence may result in incomplete substitution[91]. As a solution, perioperative administration of omegaven offers a convenient and manageable method to protect liver function[91].

Structured triglyceride-based lipid emulsions have shown greater benefits compared to physical mixtures of medium-chain triglycerides and long-chain triglycerides in restoring hepatic and immune functions, demonstrating improvements in liver function markers, including alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, albumin and bilirubin[92]. They also promote better protein metabolism, reduce tissue breakdown, enhance cellular and humoral immunity and do not elevate the liver's metabolic workload, ensuring quicker clearance and a lower risk of immune suppression[92].

For amino acids, the infusion of a balanced amino acid solution (8% Nutramin) inhibits liver regeneration following partial hepatectomy, whereas parenteral administration of an amino acid solution enriched with BCAAs (valine, leucine, isoleucine) promotes the initiation of liver regeneration more effectively than glucose or the commercial amino acid solution (8% Nutramin)[89]. Supplemental BCAAs can support protein synthesis and liver regeneration, rapidly improve liver function, inhibit development of liver cirrhosis and HCC recurrence, and if administered preoperatively, reduce ascites and serum albumin[5,31,93]. In liver cancer patients undergoing resection, perioperative administration of BCAAs was also found to effectively reduce the risk of postoperative infection, shorten hospital stays, and promote weight gain[94]. The molecular adsorbent recirculating system is a safe and effective approach for correcting low Fischer’s ratio and enhancing liver function in patients with PHLF, demonstrating unexpectedly low 60- and 90-day mortality rates compared to historical controls[95].

Prehabilitation involves a comprehensive approach, including physical exercise, nutritional optimization, and psychological support, and plays a crucial role in optimising patients before liver resection, enhancing patient resilience and ultimately improving postoperative outcomes[96]. Clinical data further support its benefits, where a multidisciplinary prehabilitation program involving physiotherapists, dietitians, and case managers showed a reduction in postoperative morbidity and social issues, improved quality-of-life, and a 16.5% cost reduction, despite participants having higher comorbidity burdens[97]. These findings highlight the importance of integrating prehabilitation into liver resection protocols to enhance patient recovery and overall surgical success. It was also found that for patients undergoing major hepatobiliary and pancreatic surgeries for malignancies, a goal-directed prehabilitation program that focused on walking and step count goals did not significantly improve functional capacity (measured by 6-minute walking distance) compared to conventional prehabilitation which comprised standard physical and nutritional support[98].

Limitations and future research

Limitations of this review include the variability in study methodologies and patient populations which limit the generalisability of the conclusions. Additionally, the focus on metabolic changes excludes other critical aspects, such as alterations in immunity, coagulation and liver function tests, which should also be taken into account to provide a full picture of the postoperative changes post-hepatectomy.