Published online Jun 28, 2015. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v7.i6.139

Peer-review started: September 16, 2014

First decision: October 28, 2014

Revised: April 20, 2015

Accepted: May 5, 2015

Article in press: May 6, 2015

Published online: June 28, 2015

Processing time: 274 Days and 4.6 Hours

Several techniques have been reported to address different endovascular device failures. We report the case of a premature deployment of a covered balloon mounted stent during endovascular repair of a post-traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF). A 50-year-old male suffered a fall resulting in loss of consciousness and multiple facial fractures. Five weeks later, he developed decreased left visual acuity, proptosis, chemosis, limited eye movements and cranial/orbit bruit. Cerebral angiography demonstrated a direct left CCF and endovascular repair with a 5.0 mm × 19 mm covered stent was planned. Once in the lacerum segment, increased resistance was encountered and the stent was withdrawn resulting in premature deployment. A 3 mm × 9 mm balloon was advanced over an exchange length microwire and through the stent lumen. Once distal to the stent, the balloon was inflated and slowly pulled back in contact with the stent. All devices were successfully withdrawn as a unit. The use of a balloon to retrieve a prematurely deployed balloon mounted stent is a potential rescue option if leaving the stent in situ carries risks.

Core tip: Increasingly complex neurovascular lesions are now amenable to endovascular therapy due to the development of new devices and techniques. However, malfunction or failure of these devices remains a potential hurdle to a successful treatment. Consequently, a growing body of reports describing rescue and salvage techniques have emerged. In this report, we discuss the endovascular retrieval of a prematurely deployed covered stent during the treatment of a traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula.

- Citation: Miley JT, Rodriguez GJ, Tummala RP. Endovascular retrieval of a prematurely deployed covered stent. World J Radiol 2015; 7(6): 139-142

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v7/i6/139.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v7.i6.139

Increasingly complex neurovascular lesions are now amenable to endovascular therapy due to the development of new devices and techniques. However, malfunction or failure of these devices remains a potential hurdle to a successful treatment. More commonly, endovascular device malfunction has been reported in the setting of intracranial aneurysm coil embolization or stent placement. Consequently, a growing body of reports describing rescue and salvage techniques has emerged[1-6]. In this report, we discuss the endovascular retrieval of a prematurely deployed covered stent during an attempted treatment of a traumatic carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF).

A 50-year-old right-handed man was repairing an elevator when he sustained a 20-foot fall, resulting in loss of consciousness. He was taken to a local hospital where a left wrist, multiple rib and craniofacial fractures were discovered. All fractures were managed conservatively. By the end of his five-week hospital stay, he began to experience a roaring tinnitus that was only mainly audible at night, horizontal diplopia, decreased visual acuity, chemosis and proptosis of the left eye.

One week later, the patient was referred to our institution to address his worsening left ocular symptoms. On initial examination, we noted a cranial and orbital bruit, decreased left visual acuity (20/100), left afferent papillary defect, proptosis, chemosis and limited eye movements in all directions. The remainder of his neurological examination was unremarkable. Computerized tomography of the head demonstrated fractures of the left zygomatic arch, left lateral orbital wall, a prominent left superior ophthalmic vein, and a left parietal hypodensity consistent with a subacute ischemic infarct. A conventional diagnostic cerebral angiogram demonstrated a left CCF in the horizontal cavernous segment of the left intracranial cavernous angiomas (ICA) (barrow type A)[7] with angiographic steal from the intracranial circulation and flow reversal into the cavernous sinus tributary veins.

Due to the symptoms of the patient and concerns for visual loss conservative management was not considered. Given the lack of established guidelines in the treatment of CCFs and our previous successful experience in the treatment of CCFs with a covered stent, it was decided to use a covered stent in the left cavernous ICA at the site of the fistula. In our experience previous cases of CCFs treated at our institution were mainly performed with coil embolization of the cavernous sinus but often requiring several procedures, recently we had a success with the use of a covered stent. Prior to the procedure, emergent internal review board consent was obtained for the off label use of a covered stent. Through a 7 French (Fr) introducer sheath (Cordis, Miami, FL) in the right femoral artery, a 7 Fr Brite Tip multipurpose catheter (Cordis, Miami, FL) was advanced into the distal cervical segment of the left ICA. We navigated a microcatheter (Excelsior SL-10, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) into the proximal left middle cerebral artery and exchanged it over a microwire (Luge Wire, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) for the covered stent delivery system. With the microwire positioned in the distal M2 division, we advanced intracranially a 5 mm × 19 mm covered stent (Graft-Master JoStent, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) over the microwire.

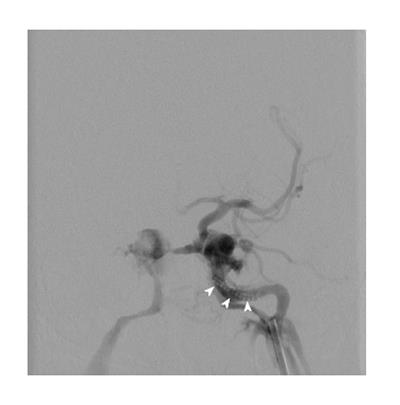

Once the stent delivery system was in the proximal vertical segment of the left cavernous ICA, we noted increased resistance and difficulty in advancing the system past the posterior genu of the cavernous segment. The guide catheter was pushed back proximally as the resistance increased, therefore we determined that the covered stent could not be delivered through our system and it had to be withdrawn. Upon withdrawal of the devices, we noted the stent was no mounted on the balloon. Fluoroscopy demonstrated that the stent had been prematurely deployed into the lacerum segment of the ICA (Figure 1) and the un-inflated balloon of the stent system was not abating the wall of the vessel.

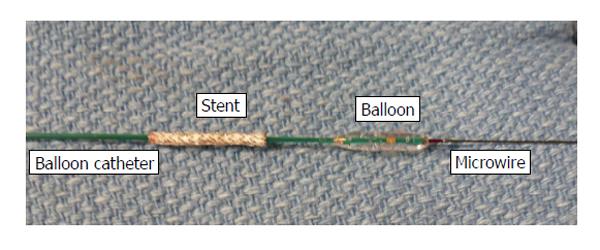

Under roadmap guidance, a 3 mm × 9 mm Maverick balloon (Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) was advanced over a 0.014 microwire (Transcend, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) through the lumen of the stent. The distal end of the microwire was positioned in the left A1. Once the balloon was distal to the stent, the balloon was inflated to a subnominal pressure and pulled back in contact with the distal end of the stent (Figure 2). The stent was dragged back over the wire to the distal end of the guide catheter. Ensuring the stent was trapped between the guide catheter and the balloon all the devices were withdrawn at once (Figure 3).

The patient in the same procedure underwent transvenous coil embolization of the cavernous sinus, however it was required to keep the patient intubated and be brought back the next day to achieve complete embolization of the fistula (coil length of 390 cm). At follow up a few weeks later, the proptosis, chemosis and bruit resolved along with improvement in the extraocular movements and visual acuity.

There is a growing body of literature focused on salvage techniques for neuroendovascular complications, and the operator must be prepared to manage intraprocedural complications including those related to device failure. Effective and successful rescue maneuvers unique to each device should be reported.

The successful use of covered stents in the treatment of CCF has been reported[8-12], but their poor navigability in the intracranial circulation is also well-described. Factors that contribute to a difficult stent delivery into the intracranial circulation include tortuous vascular anatomy, unstable positioning of the guide catheter, and poor stent navigability. The Graft-Master JoStent (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) is composed of a polytetrafluoroethylene sheet fixed between two stainless steel stents, mounted on a semi-compliant balloon that requires a ≥ 7 Fr guide catheter and ≤ 0.014 inch wire for device delivery. This design results in inherent stiffness and poor navigability of the device. Excessive application of force may not overcome the poor navigability and may lead to proximal herniation of the guide catheter or premature deployment of the stent. Our patient did not appear to have prominent tortuous vessels, consequently, we believed that we could advance the covered stent to the cavernous segment with minimal resistance. Although large series are lacking, failure to deploy a covered stent has been previously reported[13]. A better proximal support by having a telescoping system with the guide catheter supported by an additional long sheath may have helped with navigation and prevented premature deployment of the stent. A shorter covered stent (12 mm) could have been easier to advance, however we were not convinced that its length would properly have covered the fistulous point.

The prematurely deployed stent was noted after the removal of the stent delivery microcatheter and its guide wire. In addition, this resulted in loss of access to the lumen of the stent and posed the challenging task to pass a wire back through the stent. Nevertheless, we were concerned that leaving a stent not abating the wall of the vessel could increase the risk of thromboembolic complications with or without stent migration, therefore we chose to attempt the stent retrieval.

The retrieval of misplaced or malfunctioning devices in neuroendovascular procedures have been performed using snares[1], the Alligator retrieval device (Chestnut Medical, Menlo Park, CA)[3] or the Merci retriever (Concentric, Mountain View, CA)[6]. In coronary procedures however, the reported incidence of coronary stent loss or premature stent-balloon separation resulting in embolism is reported to be in the range of 0.27%-3.4%[14,15]. The retrieval in this setting often involves the use of a small distal balloon, loop snare, two wires around the stent or biopsy forceps[14-19]. This migration or premature deployment in neuroendovascular procedures is a relatively uncommon complication since most commercially available intracranial stents are self-expandable[20,21].

The technique of passing a balloon within the lumen of the stent is a well described technique in interventional cardiology for the retrieval of migrated stents[14-16,22,23]. The balloon is used to drag the stent proximally to the tip of the guide catheter. Once all are in contact (balloon-stent-guide catheter), the entire system is removed in one unit. Although in this case the rescue was successful, we acknowledge that the rescue might have carried additional challenges such as failure of retrieval and arterial dissection.

The retrieval of an early deployed balloon mounted stent is possible. The use of a balloon to drag the stent back into the guide catheter is a potential rescue option if leaving the stent in situ carries risks.

Blurred left eye vision, double vision and tinnitus developed after a fall.

Chemosis, proptosis of the left eye, an orbital bruit was noted.

An arteriovenous fistula was suspected and demonstrated with neuroimaging.

A conventional angiogram demonstrated a direct carotid-cavernous fistula (CCF).

Failure of a stent placement led to the definitive transvenous coil embolization.

Unforeseen device failure occurs. Experiences in this regard should be reported.

Covered-stent: No flow is allowed within the struts of the stent, impermeable.

Tortuous vasculature may prevent smooth navigation of rigid devices.

This was described as an interesting manuscript that reviews treatment options of a CCF, and limitations when a covered stent is planned to be used. The authors’ experience in the retrieval of a prematurely deployed covered stent may help the reader if facing a similar case.

| 1. | Dinc H, Kuzeyli K, Kosucu P, Sari A, Cekirge S. Retrieval of prolapsed coils during endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:269-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fessler RD, Ringer AJ, Qureshi AI, Guterman LR, Hopkins LN. Intracranial stent placement to trap an extruded coil during endovascular aneurysm treatment: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:248-251; discussion 251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Henkes H, Lowens S, Preiss H, Reinartz J, Miloslavski E, Kühne D. A new device for endovascular coil retrieval from intracranial vessels: alligator retrieval device. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:327-329. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Lavine SD, Larsen DW, Giannotta SL, Teitelbaum GP. Parent vessel Guglielmi detachable coil herniation during wide-necked aneurysm embolization: treatment with intracranial stent placement: two technical case reports. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:1013-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Prestigiacomo CJ, Fidlow K, Pile-Spellman J. Retrieval of a fractured Guglielmi detachable coil with use of the Goose Neck snare “twist” technique. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1999;10:1243-1247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vora N, Thomas A, Germanwala A, Jovin T, Horowitz M. Retrieval of a displaced detachable coil and intracranial stent with an L5 Merci Retriever during endovascular embolization of an intracranial aneurysm. J Neuroimaging. 2008;18:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barrow DL, Spector RH, Braun IF, Landman JA, Tindall SC, Tindall GT. Classification and treatment of spontaneous carotid-cavernous sinus fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:248-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 755] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Archondakis E, Pero G, Valvassori L, Boccardi E, Scialfa G. Angiographic follow-up of traumatic carotid cavernous fistulas treated with endovascular stent graft placement. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:342-347. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Gomez F, Escobar W, Gomez AM, Gomez JF, Anaya CA. Treatment of carotid cavernous fistulas using covered stents: midterm results in seven patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1762-1768. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hoit DA, Schirmer CM, Malek AM. Stent graft treatment of cerebrovascular wall defects: intermediate-term clinical and angiographic results. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:ONS380-ONS388; discussion ONS388-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lv XL, Li YX, Liu AH, Lv M, Jiang P, Zhang JB, Wu ZX. A complex cavernous sinus dural arteriovenous fistula secondary to covered stent placement for a traumatic carotid artery-cavernous sinus fistula: case report. J Neurosurg. 2008;108:588-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Madan A, Mujic A, Daniels K, Hunn A, Liddell J, Rosenfeld JV. Traumatic carotid artery-cavernous sinus fistula treated with a covered stent. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2006;104:969-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang C, Xie X, You C, Zhang C, Cheng M, He M, Sun H, Mao B. Placement of covered stents for the treatment of direct carotid cavernous fistulas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30:1342-1346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brilakis ES, Best PJ, Elesber AA, Barsness GW, Lennon RJ, Holmes DR, Rihal CS, Garratt KN. Incidence, retrieval methods, and outcomes of stent loss during percutaneous coronary intervention: a large single-center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2005;66:333-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Eggebrecht H, Haude M, von Birgelen C, Oldenburg O, Baumgart D, Herrmann J, Welge D, Bartel T, Dagres N, Erbel R. Nonsurgical retrieval of embolized coronary stents. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2000;51:432-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Colkesen AY, Baltali M, Acil T, Tekin G, Tekin A, Erol T, Sezgin AT, Muderrisoglu H. Coronary and systemic stent embolization during percutaneous coronary interventions: a single center experience. Int Heart J. 2007;48:129-136. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Juszkat R, Dziarmaga M, Zabicki B, Bychowiec B. Successful coronary stent retrieval from the renal artery. Cardiol J. 2007;14:87-90. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Steinberg DH, Satler LF, Pichard AD. Snare extraction of a fractured coronary stent in a saphenous vein graft. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2007;70:241-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ahmar W, Malaiapan Y, Meredith IT. Transradial retrieval of a dislodged stent from the left main coronary artery. J Invasive Cardiol. 2008;20:545-547. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kelly ME, Turner RD, Moskowitz SI, Gonugunta V, Hussain MS, Fiorella D. Delayed migration of a self-expanding intracranial microstent. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008;29:1959-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lubicz B, François O, Levivier M, Brotchi J, Balériaux D. Preliminary experience with the enterprise stent for endovascular treatment of complex intracranial aneurysms: potential advantages and limiting characteristics. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:1063-1069; discussion 1069-1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Qiao S, Gao R, Chen J, Yao M, Yang Y, Qin X, Xu B. Successful retrieval of intracoronary lost balloon-mounted stent using a small balloon. Chin Med J (Engl). 2000;113:93-94. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Kammler J, Leisch F, Kerschner K, Kypta A, Steinwender C, Kratochwill H, Lukas T, Hofmann R. Long-term follow-up in patients with lost coronary stents during interventional procedures. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:367-369. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Battal B, Chen F, El-Ghar MA, Vinh-Hung V

S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/