Published online Sep 28, 2013. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i9.345

Revised: August 9, 2013

Accepted: August 28, 2013

Published online: September 28, 2013

Processing time: 126 Days and 19.5 Hours

Xanthomas are rare bone tumors that occur more often in the appendicular skeleton and typically appear radiographically benign, with a narrow zone of transition and a sclerotic rim. We report the case of a 57-year-old woman with hyperlipidemia presenting with bilateral shoulder pain after minor trauma. Radiographic and histopathologic investigation demonstrated intraosseous xanthoma with atypical features, including multifocality, a wide zone of transition and pathologic fractures-characteristics more commonly associated with aggressive lesions such as multiple myeloma or metastasis. The diagnosis, imaging, and histological appearance of xanthoma of bone are reviewed.

Core tip: Primary xanthoma of bone is very rare, and the clinical and radiological presentation of this case is distinctly uncommon. This condition can occur in patients with both normal and abnormal lipid profiles. The radiological features are protean and can appear both aggressive and nonaggressive, hence the diagnosis can usually only be made with a biopsy.

- Citation: Ali S, Fedenko A, Syed AB, Matcuk G, Patel D, Gottsegen C, White E. Bilateral primary xanthoma of the humeri with pathologic fractures: A case report. World J Radiol 2013; 5(9): 345-348

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i9/345.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i9.345

Xanthoma is a clinically “nodular” condition resulting from improper accumulation of cholesterol or triglycerides in histiocytes, and often results in soft-tissue and subcutaneous nodules. Xanthomas of bone, however, are very rare[1]. These lesions usually occur in the appendicular skeleton, especially the long bones such as the tibia. No bone is spared, however, and lesions can occur anywhere in the appendicular or axial skeleton including the bony pelvis, spine and skull base. Most xanthomas of bone occur in patients with a hyperlipidemic state[1,2] and may be associated enzyme deficiencies such as lipoprotein lipase[3], although there have been documented cases of osseous xanthoma in patients with a normal lipid profile[4]. We present an unusual case of a woman that presented with bilateral shoulder pain and pathologic fractures after minor trauma, and was found to have bilateral primary xanthomas despite clinical and radiographic findings atypical for xanthoma of bone.

A 57-year-old woman was in her usual state of good health until she fell and sustained fractures of the bilateral proximal humeri. At this time, it was felt that the fractures were likely pathologic as aggressive appearing osteolytic lesions were seen in the humeri on radiographs. The patient was evaluated by medical oncologists who performed a metastatic workup, which was negative. There was concern that the patient may have a primary tumor of bone despite the bilaterality of the lesions.

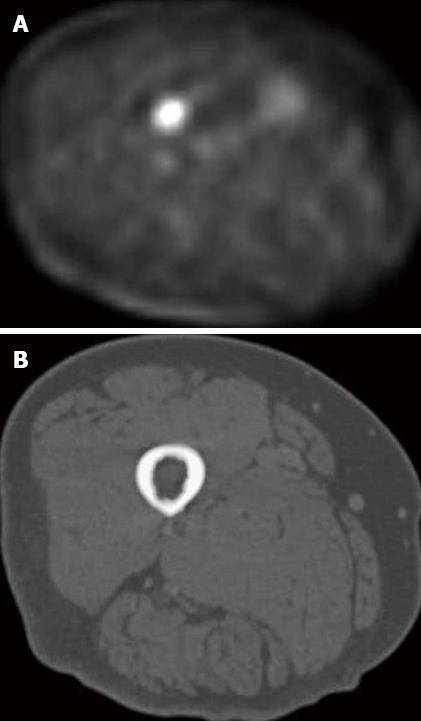

The radiographs demonstrated bilateral comminuted proximal humeral pathologic fractures, with underlying poorly defined permeative lytic lesions that extended into the diaphysis on the right, and remained confined to the proximal humerus on the left (Figure 1). There was no internal matrix, visible soft tissue mass or periosteal reaction. Whole body and axial positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was subsequently performed to evaluate the possibility of bony metastasis, and showed increased uptake of F-18 FDG in the proximal humeri and in the proximal right femur (Figures 2A, B and 3A). Although the proximal humeral uptake could have been attributed to the fractures, the proximal femoral lesion could not be as it appeared morphologically normal on CT (Figure 3B). A decision was made not to pursue an MRI, but to proceed directly to biopsy of the humeral lesions.

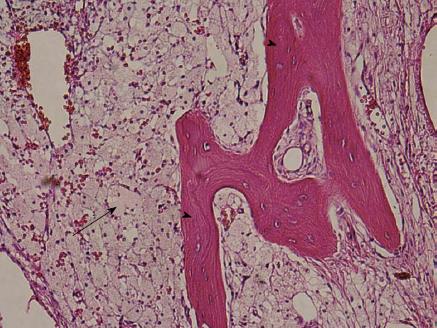

The patient was taken to the operating room for biopsy and possible resection and reconstruction. A frozen section was obtained during surgery and revealed numerous histiocytes and macrophages, but no tumor cells were seen. The entire lesion was excised and the proximal humerus was resected. The gross pathologic sample showed multiple tan colored bone and soft tissue fragments. Histology showed foamy lipidic histiocytic cells infiltrating the bone marrow (Figure 4). Immunoperoxidase staining of the histiocytic cells was positive for CD68, and negative for keratin and CD45. These findings indicated that the bone sample was histopathologically consistent with lipid granulomatosis or xanthomatosis of bone. Furthermore, the patient’s lipid profile demonstrated a triglyceride level of 1626 mg/dL and a total cholesterol level of 438 mg/dL, both markedly elevated (Table 1). HDL and LDL levels were both relatively unremarkable with values of 37 mg/dL and 107 mg/dL respectively. The rest of the biochemical and hematological profiles were normal. The combination of radiologic features, foamy histiocytic cells on histology, and elevated lipid profile is consistent with a diagnosis of osseous xanthoma, most likely secondary to the patient’s hyperlipidemic state.

| Test name | Lipid panel result (mg/dL) | Reference range (mg/dL) |

| Total cholesterol | 438 (H) | < 200 |

| Triglyceride | 1626 (H) | < 200 |

| HDL | 37 | > 45 |

| LDL | 107 | < 160 |

This patient underwent proximal humeral resection and reconstruction with endoprosthesis (Figure 5). Histological evaluation of the proximal femoral lesion was not obtained, as follow up imaging was planned. If the size and metabolic activity of the femoral lesion decreased with control of her lipid profile, then the lesions would be assumed to be additional xanthomas. Lack of change with strict lipid control would warrant further biopsy.

Two weeks after the resection, the patient was seen in clinic and had no major complaints. Her wound was dry and intact. The skin staples were removed.

The final diagnosis was primary hyperlipidemia. Subsequent management of the patient was wound care and follow up of the humeral prosthesis. Aggressive management of her triglyceride and cholesterol levels was commenced by her internist and endocrinologist, including the use of statins and diet, in order to prevent recurrence.

The variable nature of osseous xanthoma can represent a diagnostic challenge. Typically, osseous xanthoma appears lytic with a narrow zone of transition. A sclerotic rim is often completely or partly present[5], making it difficult to differentiate from more common benign lesions such as nonossifying fibroma, fibrous dysplasia, simple bone cyst or brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism[1,5]. Rarely, lesions can have an aggressive appearance with a wide zone of transition and may be multifocal resembling multiple myeloma or metastases[6], as shown in the humeri in this case. Bone expansion can also be seen[5]. Significant marrow accumulation of lipid results in a structurally weak bone, and pathologic fractures may occur especially in the weightbearing tibia, femur, and pelvis[6], but is distinctly uncommon in a nonweightbearing bone such as the humerus. Radionuclide bone scans typically show uptake of Tc99m-MDP, and multifocal lesions that are not radiographically visible may be detected[7]. PET or PET-CT scans show intense uptake of F-18 FDG. In the case presented, the maximum standardized uptake value (SUV max) of the right proximal femur lesion was 6.9, which is markedly elevated, even though the femur was morphologically normal on CT. MRI is nonspecific, with lesions showing low T1 signal, although there is often peripheral T1 hyperintensity due to lipid accumulation, and elevated T2 signal. An exophytic soft tissue component is not uncommon, and reactive bone sclerosis may result in peripheral low signal intensity on all sequences. Contrast enhancement is variable[8].

The radiologic differential diagnosis depends on the age of the patient. In a patient above 40 years, the lesions can be indistinguishable from osseous metastasis or multiple myeloma. Combined with a positive bone or PET scan, as in this case, biopsy is usually warranted. In younger patients, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, Erdheim-Chester disease, and less likely primary bone tumor should also be considered[5].

Osseous xanthoma typically occurs in the setting of hyperlipidemia, especially primary or familial hyperlipidemia[1]. It is more commonly reported in familial hyperlipidemia types IIb and III[2,9], and rarely in types I, IV, and V[9,10]. Osseous xanthoma in the absence of hyperlipidemia has also been reported[4,11].

Histologically, the typical appearance is a lesion consisting of sheets of foam cells and occasional mononuclear or multinucleated giant cells. Xanthoma lesions may stain positively with Factor 13-A, a marker characteristic of some histiocytic proliferations[11].

Treatment is typically with curettage and bone grafting and is usually curative, however internal fixation may be indicated in some cases especially after a pathologic fracture[11]. Adjuvant radiotherapy may be indicated when curettage is incomplete or difficult to achieve, as in the skull base or spine[11-13].

In conclusion, we have described an uncommon clinical and radiological presentation of osseous xanthoma, a rare cause of bone tumor. Although classically described as lytic with well-defined borders, this patient demonstrated that the radiologic characteristics of osseous xanthoma may include multifocal lesions, poorly defined margins and pathologic fractures in nonweightbearing bones. The variability of appearance of osseous xanthoma reinforces the need for tissue biopsy in diagnosis.

P- Reviewer Lipar M S- Editor Qi Y L- Editor A E- Editor Liu XM

| 1. | Dallari D, Marinelli A, Pellacani A, Valeriani L, Lesi C, Bertoni F, Giunti A. Xanthoma of bone: first sign of hyperlipidemia type IIB: a case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;274-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Inserra S, Einhorn TA, Vigorita VJ, Smith AG. Intraosseous xanthoma associated with hyperlipoproteinemia. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1984;218-222. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Torigoe T, Terakado A, Suehara Y, Kurosawa H. Xanthoma of bone associated with lipoprotein lipase deficiency. Skeletal Radiology. 2008;37:1153-1156. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Boisgard S, Bringer O, Aufauvre B, Joudet T, Kemeny JL, Michel JL, Levai JP. Intraosseous xanthoma without lipid disorders. Case-report and literature review. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67:71-74. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bertoni F, Unni KK, McLeod RA, Sim FH. Xanthoma of bone. Am J Clin Pathol. 1988;90:377-384. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yokoyama K, Shinohara N, Wada K. Osseous xanthomatosis and a pathologic fracture in a patient with hyperlipidemia. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;307-310. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kovac A, Kuo YZ, Sagar V. Radiographic and radioisotope evaluation of intra-osseous xanthoma. Br J Radiol. 1976;49:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yamamoto T, Kawamoto T, Marui T, Akisue T, Hitora T, Nagira K, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M. Multimodality imaging features of primary xanthoma of the calcaneus. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hamilton WC, Ramsey PL, Hanson SM, Schiff DC. Osseous xanthoma and multiple hand tumors as a complication of hyperlipidemia. Report of a case. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1975;57:551-553. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Siegelman SS, Schlossberg I, Becker NH, Sachs BA. Hyperlipoproteinemia with skeletal lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1972;87:228-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alden KJ, McCarthy EF, Weber KL. Xanthoma of bone: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2008;28:58-64. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Huang GS, Huang CW, Lee CH, Taylor JA, Lin CG, Chen CY. Xanthoma of the sacrum. Skeletal Radiol. 2004;33:674-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zak IT, Altinok D, Neilsen SS, Kish KK. Xanthoma disseminatum of the central nervous system and cranium. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:919-921. [PubMed] |