Published online Jan 28, 2026. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v18.i1.114552

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: January 28, 2026

Processing time: 119 Days and 21.7 Hours

Nocardia pneumonia is an infection that occurs in patients with underlying diseases. Previously, due to limited detection methods, its detection rate and typing posed significant challenges. However, with advancements in detection techniques, the detection rate has significantly increased, and different Nocardia species exhibit distinct imaging characteristics.

To retrospectively analyze the etiological and imaging features of pulmonary Nocardia pneumonia and to examine the differences in chest imaging manifestations among different Nocardia species.

The medical records of 102 patients with pulmonary nocardiosis who were admitted to Beijing Chaoyang Hospital from January 2017 to December 2024 were collected. Data including name, gender, underlying comorbidities, etiological characteristics, diagnostic methods, chest computed tomography features, and therapeutic agents were recorded.

Among the 102 patients, 55 were male and 47 were female, with a median age of 61 years. Bronchiectasis was the most common comorbidity, observed in 54 pa

Nocardia pneumonia commonly coexists with bronchiectasis. While metagenomic next-generation sequencing has greatly enhanced its detection rate, Nocardia wallacei pneumonia is distinguished on chest computed tomography by its primary presentation of bronchopneumonia, unlike other types.

Core Tip: This study highlights that bronchiectasis is the most common comorbidity in pulmonary nocardiosis. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing is a key diagnostic tool. Crucially, chest computed tomography reveals distinct imaging patterns: Nocardia wallacei primarily presents as bronchopneumonia, while other species more frequently cause consolidation with nodules/cavities. Immunosuppressed patients exhibit more diverse and complex imaging features.

- Citation: Wang HJ, Zhang YN, An L. Clinical and radiographic feature of pulmonary nocardiosis: A study of 102 cases. World J Radiol 2026; 18(1): 114552

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v18/i1/114552.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v18.i1.114552

Pulmonary nocardiosis is a rare and potentially severe opportunistic infection primarily affecting the lungs[1]. It is caused by Nocardia species, which are aerobic, Gram-positive bacteria commonly found in soil[2]. Although often associated with immunocompromised individuals, pulmonary nocardiosis can also occur in immunocompetent hosts[3].

Nocardia species are the causative agents of nocardiosis, with Nocardia asteroides being the most frequently implicated species[4]. However, other species such as Nocardia brasiliensis, Nocardia otitidiscaviarum, Nocardia transvalensis, Nocardia cyriacigeorgica (N. cyriacigeorgica), Nocardia mexicana, and Nocardia araoensis can also cause pulmonary infections[5,6]. These bacteria are typically acquired through inhalation, leading to pulmonary involvement. In immunocompromised indi

Several factors increase the risk of developing pulmonary nocardiosis, including acquired immune deficiency syndrome, organ transplantation, corticosteroid therapy, other immunosuppressive treatments and other risk factors[7]. The clinical presentation of pulmonary nocardiosis can be nonspecific, often mimicking other common respiratory infections[8]. Common symptoms include fever, cough, sputum production, chest pain, dyspnea and malaise[9].

Diagnosing pulmonary nocardiosis can be challenging due to its rarity and nonspecific clinical presentation. Diagnostic methods include traditional culture methods, which can be used to identify Nocardia species from sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage samples. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) has emerged as a valuable tool for detecting Nocardia and identifying mixed infections, which can impact prognosis[10]. Nanopore sequencing has been used for the detection of pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum[5].

Computed tomography (CT) scans are valuable for detecting pulmonary nocardiosis, often allowing earlier detection and better characterization of abnormalities compared to chest radiography. High-resolution CT can further delineate complex features such as consolidation, nodules, and cavities. Chest radiographs and CT scans can reveal various findings, including consolidation, nodules, masses, cavitation, and pleural effusion[11]. In some cases, pulmonary nocardiosis can present with endobronchial involvement, causing bronchial stenosis and mucosal lesions[12]. CT scans often reveal lung consolidation, nodules, and masses. Cavitation may also occur, and in some cases, chest wall invol

The radiographic appearance of pulmonary nocardiosis can resemble other conditions such as tuberculosis, fungal infections, and even lung cancer. Therefore, a definitive diagnosis requires microbiological confirmation. Follow-up CT scans are useful for monitoring the progression of the disease and the response to treatment[15].

Given the non-specific nature of radiographic findings, correlation with clinical and microbiological data is crucial for diagnosing pulmonary nocardiosis. A high index of suspicion is particularly important in patients with pre-existing risk factors or immunocompromising conditions. Different Nocardia species may exhibit some variations in their pathogenic mechanisms, potentially leading to subtle differences in radiographic presentation, which is not well-defined. Further research is needed to clarify these potential differences. Hence, in the present study, we report the clinical features of 102 pulmonary nocardiosis cases, especially radiographic features in those with different species of Nocardia.

We retrospectively reviewed patients with pulmonary nocardiosis admitted to Beijing Chaoyang Hospital between January 2017 and December 2024. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Nocardia was detected by a culture or next-generation sequencing from respiratory samples or blood culture with subjective and objective symptoms and laboratory test and imaging findings suggesting respiratory infection defined as pulmonary nocardiosis; (2) Had complete medical records, and chest CT and follow-up results; and (3) Aged 18 years or older.

The collected data included age, sex, comorbid conditions, clinical symptoms, diagnostic tests, chest CT findings, etiological results, therapeutic regimens, and prognosis during hospitalization. The chest CT results were based on imaging performed either at initial hospitalization or during outpatient visits prior to medication initiation. All chest CT images of pulmonary nocardiosis were independently reviewed by two physicians to mitigate subjective bias. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, approval No. 2025-ke-359, and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

One hundred and two inpatients with pulmonary nocardiosis from Beijing Chaoyang Hospital between January 2017 and December 2024 were included in this study. Fifty-five patients were male and 47 were female, with a median age of 61 years. The majority of patients had underlying diseases, including bronchiectasis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, bronchial asthma, and diabetes, among others. Only two patients had no underlying diseases, and both had a history of soil exposure. Bronchiectasis was the most common comorbidity, which was observed in 54 patients (52.9%) and in 23 (22.5%) patients with a history of immunosuppression. Among these 102 patients, 41 cases (40%) were confirmed by sputum or bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) culture, while 61 cases (60%) were diagnosed using mNGS. Nocardia gelsenkin was identified as the most prevalent pathogen in nocardial pneumonia, followed by Nocardia abscessus (N. abscessus) and then N. cyriacigeorgica (Table 1).

| Item | n (%) |

| Sex (male) | 55 (53.4) |

| Age (years) | 61 (25.89) |

| Underlying diseases | |

| Bronchiectasis | 54 (52.9) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 8 (7.8) |

| Bronchial asthma | 3 (2.9) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 11 (10.7) |

| None | 2 (1.9) |

| Immunosuppression | 23 (22.5) |

| Others | 11 (10.7) |

| Nocardia typing | |

| Asian Nocardia | 6 (6) |

| Nocardia gelsenkin | 22 (22) |

| N. wallacei | 7 (7) |

| N. abscessus | 14 (14) |

| N. otitidiscaviarum | 5 (5) |

| N. farcinica | 12 (12) |

| N. beijingensis | 2 (2) |

| N. novo | 2 (2) |

| Beautiful Nocardia | 1 (1) |

| Untyped | 30 (29) |

| Detection methods | |

| Sputum/BALF culture | 41 (36/5) |

| Sputum/BALF mNGS | 61 (12/49) |

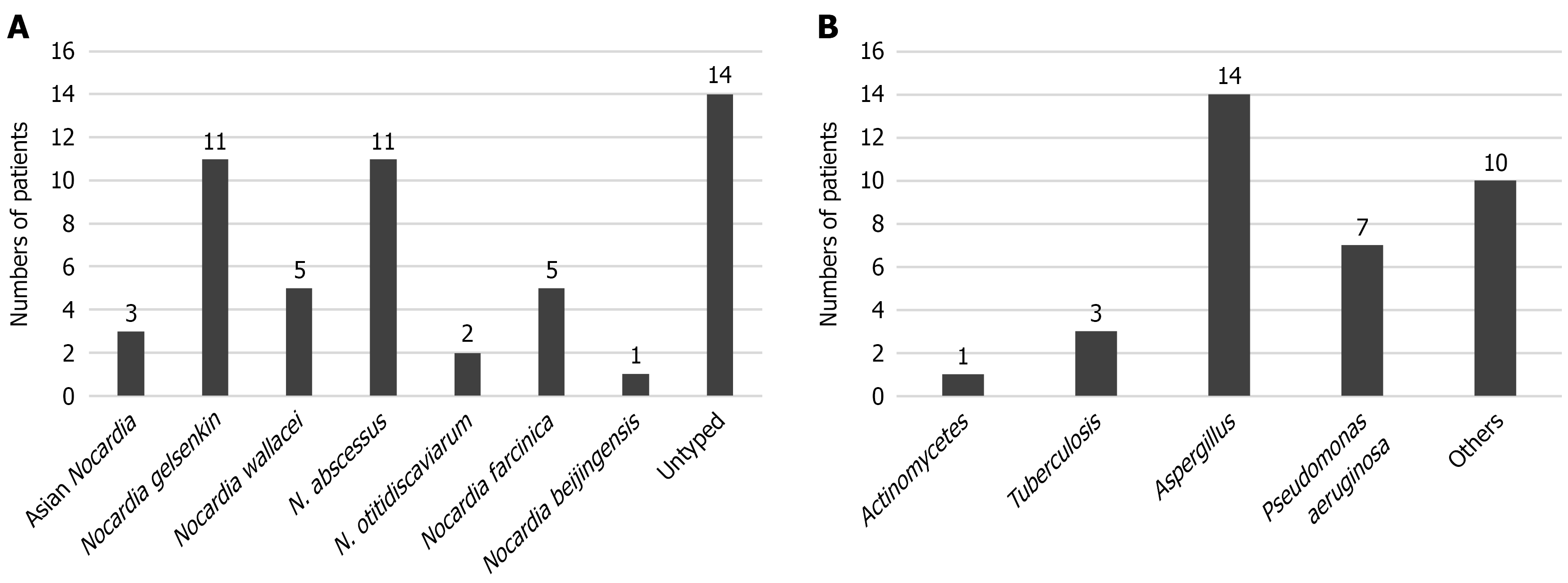

As a next step, we conducted a pathogenicity analysis of the 54 cases with bronchiectasis. Among these patients, Nocardia gelsenkin and N. abscessus remained the most prevalent Nocardia species, while Aspergillus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were identified as the predominant co-pathogens in these pulmonary nocardiosis cases (Figure 1).

Sixty-one patients (59.8%) were diagnosed with pulmonary nocardiosis by mNGS testing of sputum or BALF specimens. Among these, 50% of untyped Nocardia species were detected via mNGS. All 61 cases of pulmonary nocardiosis diag

| Item | Sputum | BALF |

| Culture positive | 1 | 1 |

| Culture negative | 11 | 48 |

| Total | 12 | 49 |

We further analyzed the annual case numbers of nocardiosis, which revealed a significant increase in diagnostic rates, particularly during 2023 and 2024. During these two years, the majority of the 47 cases were diagnosed by mNGS, with only eight cases (17%) confirmed through sputum culture (Table 3). These findings indicate that mNGS testing of sputum/BALF specimens has become the primary method for diagnosing nocardiosis and substantially enhances the detection rate of pulmonary nocardiosis.

| Year | Sputum/BALF culture | Sputum/BALF NGS | Total |

| 2017 | 9 | 0 | 9 |

| 2018 | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| 2019 | 9 | 6 | 15 |

| 2020 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 2021 | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| 2022 | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| 2023 | 7 | 17 | 24 |

| 2024 | 1 | 22 | 23 |

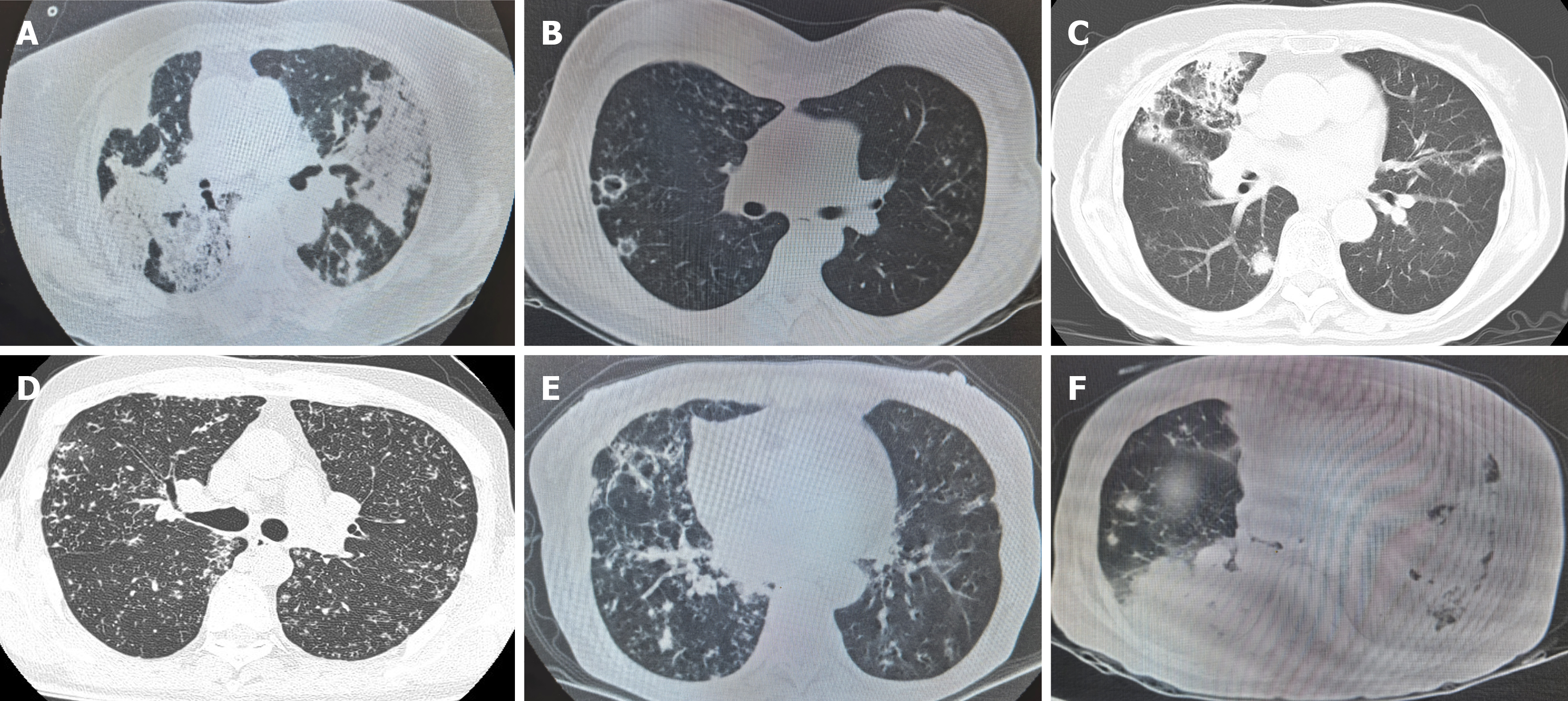

Among these 102 patients with pulmonary nocardiosis, species of Nocardia were identified by different detection methods. As shown in Table 1, Nocardia gelsenkin was the most common Nocardia species, accounting for 22%, followed by N. abscessus (14%), N. cyriacigeorgica (12%), and Nocardia wallacei (N. wallacei) (7%). By collecting the initial chest high-resolution CT scans at diagnosis, we compared and summarized their imaging characteristics, which are presented in Table 4. Among the 22 patients (22%) with Nocardia gelsenkin infection, imaging mainly showed consolidation (59%), accompanied by cavities, nodules, and pleural effusion, while a minority exhibited bronchopneumonia (9%). N. abscessus and N. cyriacigeorgica were similar to Nocardia gelsenkin, primarily manifesting as consolidation, along with cavities, nodules, bronchopneumonia, and pleural effusion. In contrast, most patients with N. wallacei pneumonia presented with bronchopneumonia (86%), accompanied by consolidation and nodules, but no cavities were observed. Additionally, based on the patients’ history of immunosuppression, we identified 18 immunocompromised patients among the 102 cases. In these 18 patients, consolidation was the most prominent imaging feature, accompanied by nodules, cavities, pleural effusion, and bronchopneumonia. The imaging characteristics were more variable and often involved multiple coexisting patterns compared to immunocompetent individuals (Table 4, Figure 2).

| Radiographic features | Immunosuppression (18/102) | Nocardia gelsenkin (22/102) | N. abscessus (14/102) | N. farcinica (12/102) | N. wallacei (7/102) | Asian Nocardia (6/102) |

| Consolidation | 13 | 13 | 11 | 9 | 1 | 4 |

| Nodules | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Cavitation | 5 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 2 |

| Pleural effusion | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Bronchopneumonia | 6 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 2 |

Sixty-one of the 102 patients received sulfonamide monotherapy alone. In terms of combination therapy, minocycline was the most frequently used drug in combination with sulfonamides, followed by amoxicillin, ceftriaxone, imipenem, amikacin, and linezolid. The most common oral agents combined with sulfonamides were amoxicillin and minocycline. In cases of sulfonamide allergy or intolerance, the most frequently adopted alternative regimen was linezolid combined with minocycline, followed by minocycline monotherapy or contezolid. The treatment course typically lasted from 6 months to 12 months, with the longest course in one patient extending to two years (Table 5).

| Medications | n |

| Sulfonamide monotherapy | 61 |

| + Ceftriaxone | 6 |

| + Minocycline | 8 |

| + Linezolid | 3 |

| + Imipenem | 6 |

| + Amikacin | 5 |

| + Amoxicillin | 7 |

| Other medications | |

| Linezolid + minocycline | 3 |

| Minocycline | 2 |

| Contezolid | 1 |

Nocardia pneumonia remains a formidable diagnostic and therapeutic challenge in contemporary medicine. Despite advances in microbiological identification and imaging, its insidious nature and propensity to mimic other pulmonary pathologies such as tuberculosis, fungal infections, or malignancy frequently led to critical delays in diagnosis and treatment[16].

Nocardiosis primarily affects individuals with compromised immune systems, but it can also occur in immunocompetent individuals. Several underlying conditions have been identified as risk factors, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, autoimmune diseases, hematological malignancies, and acquired immune deficiency syndrome[17]. Bronchiectasis is increasingly recognized as a risk factor for Nocardia infection. Nocardia can colonize or cause infection in individuals with bronchiectasis, with the structural lung abnormalities associated with bronchiectasis predisposing individuals to Nocardia-related issues[17]. The improved diagnostic techniques currently available have enhanced the detection and differentiation of Nocardia strains compared to previous studies[18]. Molecular methods, such as 16S rRNA sequencing and mNGS, have enabled more accurate identification of Nocardia species[19]. In contrast to previous studies, our research demonstrates that since the application of mNGS, the detection rate of Nocardia has significantly increased. Among our patients with Nocardia pneumonia, half had bronchiectasis, while only 23% had a history of immunosuppression.

Nocardia species can cause a variety of infections, and imaging plays a crucial role in their diagnosis and management. Different Nocardia species may exhibit distinct imaging features, although considerable overlap exists, and findings should be interpreted in the context of clinical and microbiological data[20]. Common imaging findings include: Nodules and masses: Multiple pulmonary nodules or masses are frequently observed. These can vary in size and distribution[21]. Cavitary lesions can occur within the nodules or masses. Patchy or lobar consolidation may be present, mimicking pneumonia[20]. Pleural effusion: Effusions are possible, although less common[22]. Some cases also demonstrated micronodular densities, bronchial wall thickening, and bronchiectasis. In our study, consolidation was observed to be the most common imaging finding, often accompanied by nodules, cavitation, and pleural effusion. However, N. wallacei infection most frequently presented as bronchopneumonia, which is the first report of this finding in both domestic and international studies. Patients with bronchiectasis have abnormal lung structures, which makes it easier for pathogens to colonize and cause infections. Additionally, Nocardia wallacei may induce an acute inflammatory response in the host characterized predominantly by neutrophil infiltration. This pattern of inflammation is more likely to result in bron

In immunocompetent patients, pulmonary nocardiosis can present with similar radiographic findings to non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections, such as disseminated micronodular densities, bronchial wall thickening, and bronchiectatic changes. In our study, chest imaging of immunocompromised patients primarily showed consolidation, which rarely appeared as an isolated finding. It was typically accompanied by nodules, cavitation, pleural effusion, and bronchopneumonia.

Our study has several limitations, including a small sample size and single-center design. Among the 102 patients included, some were historically diagnosed cases in which the specific Nocardia species could not be identified, which may have impacted the overall findings. However, this study remains the first to report distinct imaging differences between N. wallacei pneumonia and pneumonia caused by other Nocardia species.

Nocardia pneumonia commonly coexists with bronchiectasis. Although mNGS has greatly enhanced its detection rate, N. wallacei pneumonia is distinguished on chest CT by its primary presentation of bronchopneumonia, unlike other types.

| 1. | Chen Y, Fu H, Zhu Q, Ren Y, Liu J, Wu Y, Xu J. Clinical Features of Pulmonary Nocardiosis and Diagnostic Value of Metagenomic Next-Generation Sequencing: A Retrospective Study. Pathogens. 2025;14:656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oliveira Cabrita BM, Correia S, Jordão S, Correia de Abreu R, Alves V, Seabra B, Ferreira J. Pulmonary nocardiosis: A Single Center Study. Respir Med Case Rep. 2020;31:101175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gieger A, Waller S, Pasternak J. Nocardia Arthritidis Keratitis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2017;9:91-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alp E, Yildiz O, Aygen B, Sumerkan B, Sari I, Koc K, Couble A, Laurent F, Boiron P, Doganay M. Disseminated nocardiosis due to unusual species: two case reports. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:545-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li D, Liu Q, Xi X, Huang Z, Zhu C, Ding R, Zhang Q. Case Report: Nanopore Sequencing-Based Detection of Pulmonary Nocardiosis Caused by Nocardia Otitidiscaviarum in an Immunocompetent Patient. Infect Drug Resist. 2025;18:1753-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tajima Y, Tashiro T, Furukawa T, Murata K, Takaki A, Sugahara K, Sakagami A, Inaba M, Marutsuka T, Hirata N. Pulmonary Nocardiosis With Endobronchial Involvement Caused by Nocardiaaraoensis. Chest. 2024;165:e1-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang D, Jiang Y, Lu L, Lu Z, Xia W, Xing X, Fan H. Cushing's Syndrome With Nocardiosis: A Case Report and a Systematic Review of the Literature. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:640998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Peng Y, Dong X, Zhu Y, Lv H, Ge Y. A rare case of pulmonary nocardiosis comorbid with Sjogren's syndrome. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e23902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sadamatsu H, Takahashi K, Tashiro H, Komiya K, Nakamura T, Sueoka-Aragane N. Successful treatment of pulmonary nocardiosis with fluoroquinolone in bronchial asthma and bronchiectasis. Respirol Case Rep. 2017;5:e00229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Miyaoka C, Nakamoto K, Shirai T, Miyamoto M, Sasaki Y, Ohta K. Pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia exalbida mimicking lung cancer. Respirol Case Rep. 2019;7:e00458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Al Umairi RS, Pandak N, Al Busaidi M. The Findings of Pulmonary Nocardiosis on Chest High Resolution Computed Tomography: Single centre experience and review of literature. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2022;22:357-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yadav P, Kumar D, Meena DS, Bohra GK, Jain V, Garg P, Dutt N, Abhishek KS, Agarwal A, Garg MK. Clinical Features, Radiological Findings, and Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Pulmonary Nocardiosis: A Retrospective Analysis. Cureus. 2021;13:e17250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Lee HN, Do KH, Kim EY, Choe J, Sung H, Choi SH, Kim HJ. Comparative Analysis of CT Findings and Clinical Outcomes in Adult Patients With Disseminated and Localized Pulmonary Nocardiosis. J Korean Med Sci. 2024;39:e107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hu Y, Ren SY, Xiao P, Yu FL, Liu WL. The clinical and radiological characteristics of pulmonary cryptococcosis in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21:262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Su R, Wen Y, Liufu Y, Pan X, Guan Y. The Computed Tomography Findings and Follow-up Course of Pulmonary Nocardiosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2023;47:418-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gonzalez LM, Venkatesan R, Amador P, Sanivarapu RR, Rangaswamy B. TB or Not TB: Lung Nocardiosis, a Tuberculosis Mimicker. Cureus. 2024;16:e55412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Steinbrink J, Leavens J, Kauffman CA, Miceli MH. Manifestations and outcomes of nocardia infections: Comparison of immunocompromised and nonimmunocompromised adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Church D, Peirano G, Ugarte-Torres A, Naugler C. Population-based microbiological characterization of Nocardia strains causing invasive infections during a multiyear period in a large Canadian healthcare region. Microbiol Spectr. 2025;13:e0091425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jiao M, Ma X, Li Y, Wang H, Liu Y, Guo W, Lv J. Metagenomic next-generation sequencing provides prognostic warning by identifying mixed infections in nocardiosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:894678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Martínez R, Reyes S, Menéndez R. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis and prognosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2008;14:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cooper CJ, Said S, Popp M, Alkhateeb H, Rodriguez C, Porres Aguilar M, Alozie O. A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bounoua F, Daoudi N, Aghrouch M, Hanchi AL, Soraa N, Serhane H, Moubachir H. Pleuropulmonary nocardiosis, an unusual radiological presentation: Case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18:2725-2729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sia JK, Rengarajan J. Immunology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infections. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/