Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.116172

Revised: November 14, 2025

Accepted: January 4, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 97 Days and 6.8 Hours

Myocardial infarction (MI) incidence is increasing in adults aged < 40 years, however, as many as 25% may occur with no traditional risk factors.

To look at non-traditional risk factors for early onset MI.

Based on the guidance of PRISMA-2020, search of PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials between April 2015 and April 2020 for observational studies focusing on the association between non-traditional risk factors and MI in adults aged 18-40 years. Two reviewers independently screened studies, extracted data and checked quality using Newcastle-Ottawa Scale or Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality checklist. The protocol was registered in PROSPERO, No. CRD420251061098.

Thirteen studies (7 cohort, 4 case-control, 2 cross-sectional) from 11 countries met inclusion criteria with a sample size ranging from 154 participants in a pilot case-control study to 5.7 million people in a United States National Inpatient Sample analysis. Psychosocial factors showed consistent associations: Depression showed an MI risk 1.6-3.1-fold higher and being unpartnered was associated with a post-MI readmission risk that was 28%-31% higher. Autoimmune conditions had the greatest associations, with human immunodeficiency virus infection quadrupling odds of MI (4.06), and the risk of systemic lupus erythematosus doubling (2.12). Obstructive sleep apnea increased major adverse cardiovascular events by almost four times (hazard ratio = 3.87). Adhering to the Mediterranean diet was protective (odds ratio = 0.55). Accelerated biological aging (shortening of telomeres) separated young patients with MI from controls. Traditional risk factors did not account for up to 30% of MI cases in each of the cohorts. Most studies were of moderate to high quality, although causes of heterogeneity in design and age stratification of participants mixtures limited causality inference.

Non-traditional psychosocial, autoimmune, inflammatory, and lifestyle factors play an important role in the risk of MI in young adults. Integrating these factors into risk prediction models could improve the early identification of high-risk individuals and target prevention strategies for this vulnerable population.

Core Tip: Non-traditional risk factors such as psychosocial stressors, autoimmune disorders, biological aging and specific lifestyle and environmental exposures play a significant role in myocardial infarction risk and outcome among individuals aged < 40 years. Psychosocial factors like depression, low socioeconomic status, and unpartnered status were significantly associated with adverse events, especially among young women. Autoimmune diseases and inflammation indicators, as well as sleep disorders and unhealthy lifestyle patterns, additionally improved the risk.

- Citation: Patel T, Farhan M, Bhatt NK, Fatah HA, Peniel JJ, Kaulgud VV, Mathew T, Bapat AM, Harazeen WS, Alatta AN, Awosika A. Non-traditional risk factors for myocardial infarction in adults under forty: A systematic review of emerging trends. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(2): 116172

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i2/116172.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i2.116172

Coronary artery disease (CAD) and acute myocardial infarction (MI) are major global causes of morbidity and mortality for which the burden is rising among younger adults[1,2]. Although MI has been described as a disease of the elderly for several decades, recent epidemiological data suggest that the relative incidence of MI events among the young is in

This gap in risk prediction has led to increasing recognition of non-traditional risk factors in the pathogenesis of MI among young adults[9]. Non-traditional risk factors are defined as exposures or conditions not routinely included in standard cardiovascular risk prediction models such as Framingham, Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD), or Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation[6,10]. These encompass a diverse range of factors, including chronic inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), human immu

Identification and analysis of atypical risk factors are essential in youth because they frequently have atypical presentations, non-atherosclerotic etiologies, and are often underrepresented in clinical trials[13-15]. These unique risk profiles and etiologies are not sufficiently accounted for in current guidelines and risk prediction models, which have largely been extrapolated from older populations[6,16]. This calls for improved risk stratification methodology and prevention st

Previous review studies suggest a significant role for non-classical risk factors-especially HIV, SLE, and obstructive sleep apnea-in MI risk in young adults but the generalizability of such associations has usually been limited by older data, more restricted scope or less systematic approaches[8]. The review is unusual by its systematic and comprehensive approach, study selection, data extraction and quality checking. A methodologically sound and focused synthesis brings important gaps in the current literature on risk for MI in young adults and highlights incorporation of non-traditional risk factors in risk assessment and dissemination aimed at young adults at risk for MI.

This systematic review was completed following the PRISMA 2020 guidelines[17] and was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (registration ID: CRD420251061098). The review set out to collate and critically evaluate existing evidence for non-traditional risk factors for MI in young adults over 18 years of age but below 40 years, by employing a structured and transparent approach to study selection, data extraction and quality appraisal. Any modifications to the protocol were entered into PROSPERO with date, description and rationale.

The review was designed using the Population-Exposure-Outcome framework.

Population: Adults aged 18-40 years diagnosed with MI (including ST-elevation MI and non-ST-elevation MI). Adults aged under 40 years with MI were the primary target population. Given the limited number of strictly age-restricted studies, we also included studies with broader age ranges if relevant subgroup data could be extracted or if the majority of participants were under 40.

Exposure: Non-traditional risk factors, explicitly defined as exposures not routinely included in standard cardiovascular risk models (e.g., Framingham, ASCVD, Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation). These include psychosocial stressors (e.g., depression, marital status, SES), autoimmune diseases (e.g., SLE, RA), substance use (e.g., recreational drugs, cannabis, amphetamines, alcohol), environmental exposures (e.g., air pollution, microplastics, periodontitis), sleep disorders (e.g., OSA), and novel biomarkers [e.g., lipoprotein(a), high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, elevated hair cortisol]. Moderately prevalent conditions such as obesity were classified as traditional risk factors and excluded from the primary analysis, while cannabis use was included as non-traditional.

Outcomes: The primary outcome was the occurrence of MI or quantitative effect estimates (odds ratios, hazard ratios, or relative risks) linking non-traditional exposures to MI in the specified age group.

Study design: Observational studies (cohort, case-control, cross-sectional), large registries, and studies providing stratified data for adults under 40.

Language: Studies published in English were included; non-English studies were considered if translation resources were available.

Exclusion criteria: Reviews, editorials, conference abstracts, animal studies, in vitro studies, and studies not primarily addressing MI or non-traditional risk factors in the target population were excluded. Studies focused exclusively on traditional risk factors (e.g., hypertension, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, diabetes, obesity) or lacking stratified data for adults under 40 were also excluded.

A systematic search strategy was employed in the following electronic databases: PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, Scopus and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials. Reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were also used as such. The last search was run on 28 April 2025. A search strategy based on a combination of controlled and free-text terms, adjusted to each database (e.g., Medical Subject Heading, Emtree) was created. Search terms were “myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”, “young adults”, “non-traditional risk factors”, “psychosocial stress”, “autoimmune disease”, “substance abuse”, “environmental exposure”, and “biomarkers”. Boolean operators were used as appropriate.

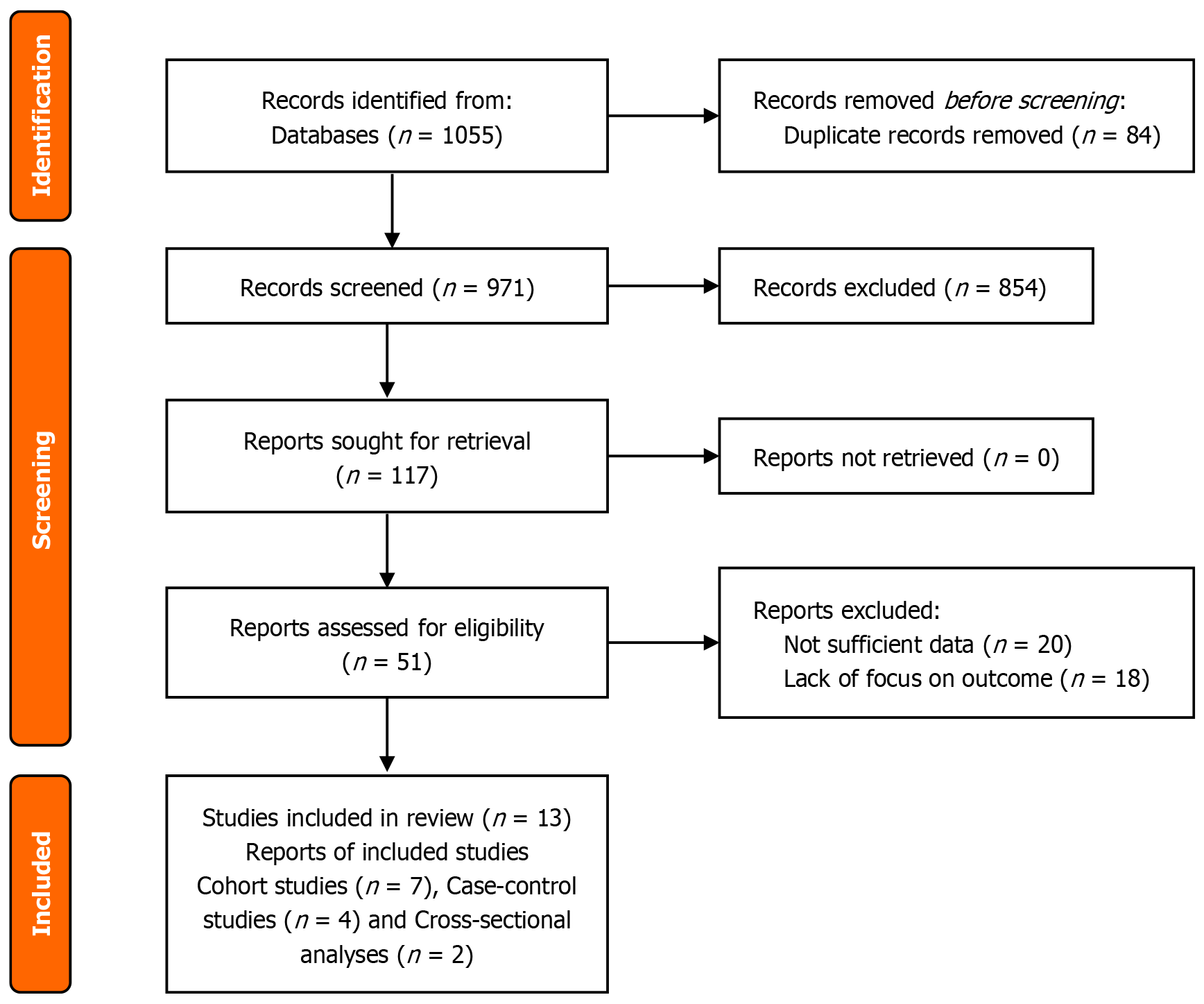

All records identified from the database search were imported into Rayyan systematic review management platform for deduplication. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two reviewers to assess relevance according to the pre-specified inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were then retrieved and assessed in detail by the same reviewers. Discrepancies in study selection were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The study selection process was documented using the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram, which details the number of records identified, screened, excluded (with reasons), and included in the final review (PRISMA, 2020).

Data extraction was conducted independently by two reviewers using a standard form of data extraction that was designed for this review. Data extraction included study features [author(s), year, country, design, sample size], par

The risk of bias in all included cohort and case control studies was evaluated with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which is an assessment of quality across domains of selection, comparability and outcome/exposure. The two included cross-sectional studies were evaluated using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) methods checklist used to evaluate study quality based on 11 items. All studies were independently scored by two reviewers with disag

Since heterogeneity in design, populations and exposures is anticipated, narrative synthesis was carried out. Results were compiled thematically by type of non-orthodox risk factor (e.g., psychosocial, environmental, inflammatory, autoimmune, lifestyle) and summarized with effect estimates and adjustment for confounders. The findings were summarised in narrative and tabular form. Then PRISMA flow diagram was used to describe the selection process of the study, and tables were designed to show the characteristics of the studies (participants characteristics, exposure details, and out

Publication bias was taken into account, as studies showing significant associations are arguably more likely to get published. Selection bias arising from differing definitions of the term “young” and severity of MI was also discussed as a limitation.

A systematic literature search was conducted in four major electronic databases, namely, PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Library and Web of Science, yielding 1055 studies. After duplicate removal there were 971 studies left for title and abstract screening. The full text review resulted in the inclusion of 13 studies in the final synthesis. The flowchart of the study selection is shown in Figure 1.

Thirteen observational studies[18-30] met the inclusion criteria, encompassing diverse designs: Cohort studies (n = 7), case-control studies (n = 4) and cross-sectional analyses (n = 2). These studies spanned 11 countries, including high-income (United States, Sweden, Italy) and low/middle-income regions (India, China, South Korea), reflecting global heterogeneity in risk factor profiles. Sample sizes ranged from 154 participants in a pilot case-control study[21] to 5.7 million in a United States National Inpatient Sample analysis[18]. While most studies focused on adults aged 18-55, five provided stratified data for populations under 45 (Table 1)[19-21,28,30].

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Sample size | Age range | Sex distribution | Comorbidities | MI classification |

| Krittanawong et al[18], 2020 | United States | Retrospective cohort (NIS) | 5764755 | < 55 (mean 45.1 AMI) | 66.6% men, 33.4% women (AMI) | Obesity, smoking, HTN, diabetes, HIV, SLE, OSA, RA | STEMI, NSTEMI |

| Zhu et al[19], 2024 | United States | Prospective cohort (VIRGO) | 2979 | 18-55 (median 48) | 67.2% women, 32.8% men | HTN, diabetes, obesity, smoking, alcohol abuse, prior CVD, COPD | STEMI, NSTEMI, EF |

| Dreyer et al[20], 2021 | United States | Prospective cohort (VIRGO) | 2979 | 18-55 (mean 47.1) | 67.4% women, 32.6% men | HTN, diabetes, obesity, smoking, prior AMI, COPD | STEMI, NSTEMI |

| Gupta et al[21], 2020 | India | Case-control | 154 (77 MI, 77 controls) | 18-45 (mean 35.3 MI) | 65 men/12 women (MI), 58 men/19 women (controls) | Excluded smokers, diabetics, BMI > 35 | AWMI, IWMI, LWMI |

| Cho et al[22], 2019 | South Korea | Population-based cohort | 2705090 | 20 + (stratified) | Not split, large population | HTN, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, SES, depression | AMI (ICD-10) |

| Fan et al[23], 2019 | China | Prospective cohort | 804 | 18-85 (mean 57.5) | 82.6% men | HTN, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, prior MI/PCI, smoking | ACS (STEMI/NSTEMI/UA) |

| Smolderen et al[24], 2015 | United States, Spain, Australia | Cohort (VIRGO) | 3572 | 18-55 (median 48) | 67.1% women, 32.9% men | HTN, diabetes, obesity, smoking, hypercholesterolemia, prior AMI, CHF | STEMI, NSTEMI |

| Turati et al[25], 2015 | Italy | Case-control | 760 cases, 682 controls | 19-79 (median 61 MI) | 76.3% men (MI) | HTN, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, BMI | Non-fatal AMI |

| Orth-Gomér et al[26], 1986 | Sweden | Case-control | 210 (89 MI, 121 controls) | 18-45 (mean 39.5) | 89 men (MI), 121 men (controls) | HTN, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, smoking | MI (survivors < 45) |

| Zhao et al[27], 2023 | China | Cross-sectional | 8103 | 18-99 (mean 50.3) | 53.5% women, 46.5% men | HTN, diabetes, obesity | Not MI-specific |

| Head et al[28], 2019 | United States | Cross-sectional autopsy (PDAY) | 2651 | 15-34 (mean 24.8) | 75% men, 25% women | Excluded major comorbidities | Subclinical atherosclerosis |

| Lu et al[29], 2022 | United States | Case-control (VIRGO/NHANES) | 2264 AMI, 2264 controls | 18-55 (median 48) | 68.9% women, 31.1% men | HTN, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, depression, low income, family history | STEMI, NSTEMI, type 1 |

| Jariwala et al[30], 2022 | India | Retrospective, multicenter | 3656 | < 45 (mean men 37.4, women 41.1) | 69.2% men, 30.8% women | HTN, diabetes, overweight, dyslipidemia, family history, smoking, alcoholism | ACS (STEMI/NSTEMI/UA) |

Young adults with MI exhibited distinct demographic profiles across studies. Women constituted 33%-68% of cohorts, with higher representation in United States-based studies[19,24]. Traditional risk factors like hypertension (28%-64%), smoking (12%-60%), and obesity (20%-51%) remained prevalent but failed to explain up to 30% of MI cases in cohorts excluding these factors[21,28]. Notably, 13% of autopsied young adults (15-34 years) had accelerated coronary atherosclerosis unaccounted for by traditional risk factors[28]. Table 1 presents the study characteristics and participant de

Psychosocial stressors consistently emerged as significant predictors of MI incidence and adverse post-MI outcomes in young adults. Two large United States cohort studies[19,20] found that unpartnered status (single, divorced, or widowed) was associated with a 28%-31% increased risk of 1-year all-cause readmission after MI [adjusted hazard ratio (HR) = 1.28-1.31], with unpartnered women facing the highest risk. Depression, measured by Patient Health Questionnaire-9, was also more prevalent in women with MI (39%) than in men (22%) and independently increased MI risk [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 1.64-3.09][24,29]. Low SES, defined by income or education, amplified risk synergistically with depression, contributing to a 47% higher incidence of MI in South Korean adults [HR = 1.47, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.36-1.60][22]. Across studies, the association between depression and MI was consistent, though the magnitude of effect varied by sex and measurement method.

Accelerated biological aging, as measured by telomere length, was strongly associated with MI in young adults, particularly in those without traditional risk factors. Gupta et al[21] found that MI patients had telomeres nearly seven times shorter than controls (mean T/S ratio 0.115 vs 0.792, P < 0.0001), with the difference most pronounced among women. However, this association was reported in a small case-control study, and longitudinal risk estimates were not available.

Autoimmune diseases demonstrated some of the strongest associations with MI risk. Krittanawong et al[18] reported that HIV infection quadrupled the odds of MI (OR = 4.06, 95%CI: 3.48-4.71), and SLE doubled the risk (OR = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.89-2.39) in young adults. Interestingly, RA was associated with a slightly reduced risk (OR = 0.83, 95%CI: 0.76-0.89), possibly reflecting treatment effects or surveillance bias. These findings were consistent across large administrative datasets, but stratified data for those under 40 were limited.

Environmental and occupational exposures also contributed to MI risk. OSA was associated with a 3.9-fold higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after one year (HR = 3.87, 95%CI: 1.20-12.46)[23], though the overall association was more modest and not limited to young adults. Night shift work and low job autonomy explained 5% of MI risk variance in Swedish men under 45[26]. Adherence to a Mediterranean diet was protective, halving the risk of non-fatal MI (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.40-0.75)[25]. Short sleep duration (≤ 6 hours) worsened cardiovascular health profiles and increased the odds of hypertension and dyslipidemia[27], though the outcome was not MI specifically. Exposure details and outcomes of every study is presented in Table 2.

| Study ID | Non-traditional risk factors assessed | Measurement methods | Outcome measures | Effect estimates (OR/HR/RR with 95%CI) | Covariates adjusted for |

| 1 | HIV, SLE, OSA, RA | ICD-9 codes (NIS) | AMI risk | HIV: OR = 4.06 (3.48-4.71); SLE: OR = 2.12 (1.89-2.39); OSA: OR = 1.16 (1.12-1.20); RA: OR = 0.83 (0.76-0.89) | Age, sex, race, BMI, DM, HTN, HLD, CKD, smoking |

| 2 | Marital/partner status, depression, social support, stress | Structured interview, PHQ-9, Social Support Inventory, Perceived Stress Scale | 1-year all-cause readmission | HR = 1.31 (1.15-1.49) unpartnered vs partnered; adjusted HRs for demo/SES/clinical/psychosocial | Age, sex, race, SES, clinical, psychosocial |

| 3 | Depression, social support, stress, SES | PHQ-9, Social Support Inventory, PSS, SES data | 1-year all-cause readmission | HR = 1.28 (1.15-1.42) unpartnered vs partnered; adjusted HRs | Age, sex, race, MI severity, comorbidities, psychosocial |

| 4 | Telomere length (biological aging) | qPCR for telomere length | Telomere length in MI vs controls | Mean T/S ratio MI 0.115 vs controls 0.792 (P < 0.0001); shorter in MI | Age, gender, BMI |

| 5 | Socioeconomic status, depression | Insurance premium, ICD-10 codes | AMI incidence | HR low SES vs high 1.16 (1.14-1.19); HR depression vs none 126 (1.21-1.31) | Age, sex, comorbidities |

| 6 | OSA | Polygraphy (AHI ≥15) | MACCE, unstable angina | HR = 1.55 (0.94-2.57) MACCE; HR = 3.87 (1.20-12.46) MACCE after 1 years | Age, sex, BMI, HTN, diabetes, prior MI/PCI |

| 7 | Depression, psychosocial stress | PHQ-9, PSS, interview | Prevalence of depressive symptoms at AMI | Women: 39% PHQ-9 ≥ 10, men: 22%; adjusted OR for women 1.64 (1.36-1.98) | Age, sex, SES, comorbidities |

| 8 | Mediterranean diet adherence | Food Frequency Questionnaire, MDS | Non-fatal AMI | MDS ≥ 6: OR = 0.55 (0.40-0.75); per point: OR = 0.91 (0.85-0.98) | Age, sex, BMI, HTN, diabetes |

| 9 | Type A behavior, psychosocial work, education | Jenkins Activity Survey, work environment survey | MI risk, variance explained | Work monotony/poor discretion 5% variance; type A 2%; education NS | Age, sex, education |

| 10 | Sleep duration | Self-report, AHA CVH score | Ideal CVH, BP, glucose, cholesterol | ≤ 6 hours sleep: OR = 1.38 (1.15-1.67) for non-ideal CVH | Age, sex, BMI, comorbidities |

| 11 | Unexplained (likely non-traditional) risk | Autopsy, lesion quantification | Subclinical atherosclerosis | OR high-growth group per year age: 1.125 (1.063-1.190) | Age, cholesterol, BMI, HbA1c, CRP |

| 12 | Depression, low income, family history | PHQ-9, interview, lab, SES | First AMI, PAFs | Women: Depression OR = 3.09 (2.37-4.04); low income OR = 1.79 (1.28-2.50) | Age, sex, SES, comorbidities |

| Men: Depression OR = 1.77 (1.15-2.73) | |||||

| 13 | Hypothyroidism, CTD, RHD, takayasu, SCAD, OCP use | Medical record, interview, labs | Prevalence, in-hospital outcomes | Non-traditional RFs rare; no adjusted effect estimates; in-hospital mortality 1.77%-2% | Age, sex |

Overall, the association between psychosocial stress, depression, and MI was consistent across studies, with stronger effects observed in women. Findings for inflammatory and autoimmune markers were also robust, although some heterogeneity was noted in the strength of association and the populations studied. For example, while HIV and SLE consistently increased MI risk, the association for RA was inverse in the largest cohort. Evidence for environmental and lifestyle factors was generally supportive but sometimes limited by study design or outcome definitions (e.g., sleep duration studies assessed cardiovascular health, not MI directly). The role of telomere length as a marker of biological aging was supported by a single small study, and further research is needed to confirm this association. Table 3 presents the summary of evidence strength.

| Risk factor category | Number of studies | Direction of association | Effect estimates (range) | Strength of evidence |

| Depression/psychosocial | 5 | Positive (risk ↑) | OR = 1.64-3.09, HR = 1.28-1.31 | Strong |

| Low socioeconomic status | 3 | Positive (risk ↑) | HR = 1.16-1.47 | Moderate |

| Autoimmune (HIV, SLE) | 2 | Strong positive (risk ↑) | OR = 2.12-4.06 | Strong |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1 | Negative (risk ↓) | OR = 0.83 | Emerging |

| Telomere length | 1 | Positive (risk ↑, shorter TL) | T/S ratio 0.115 vs 0.792 | Emerging |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 1 | Positive (risk ↑) | HR = 1.55-3.87 | Moderate |

| Mediterranean diet | 1 | Negative (risk ↓) | OR = 0.55 | Moderate |

| Short sleep duration | 1 | Positive (risk ↑) (CV health) | OR = 1.38 | Emerging |

| Occupational stress | 1 | Positive (risk ↑) | 5% variance explained | Emerging |

Subgroup analyses revealed notable effect modification by sex, age, SES, and comorbidities. In a large administrative database, HIV and SLE were strongly associated with MI risk in young adults, but stratified data for those under 40 were not available[18]. Two cohort studies found that unpartnered status was linked to higher 1-year readmission rates after MI, especially among women, though the association was attenuated after psychosocial adjustment and only one study found a significant sex-marital status interaction[19,20]. Age-stratified analysis showed telomere length was especially reduced in MI patients aged 31-45, with the difference most pronounced in females[21]. Combined low SES and depression conferred a substantially higher MI risk[22]. The protective effect of a Mediterranean diet was more evident in those with lower BMI or without hypertension[25]. Sleep duration analyses showed that short sleep (≤ 6 hours) was associated with non-ideal cardiovascular health, though not specifically MI[27]. Details of these analyses are presented in Table 4.

| Study ID | Subgroup (e.g., sex, age, region) | Effect estimates (OR/HR/RR with 95%CI) | Notes |

| 1 | Age (< 40 vs 40-55), sex | HIV: OR = 4.06 (3.48-4.71); SLE: OR = 2.12 (1.89-2.39); OSA: OR = 1.16 (1.12-1.20) for MI risk in young adults | No stratified data < 40; large administrative database; cross-sectional analysis of hospitalizations |

| 2 | Sex (women vs men), marital status (unpartnered vs partnered) | HR = 1.31 (1.15-1.49) unpartnered vs partnered for 1-year readmission; unpartnered women: 37.6% readmission vs unpartnered men: 26.8% | No significant sex-marital status interaction (P = 0.69); effect attenuated after psychosocial adjustment |

| 3 | Sex, marital status | HR = 1.28 (1.15-1.42) unpartnered vs partnered for 1-year readmission; unpartnered women had highest readmission | Significant sex-marital status interaction; psychosocial factors partially mediate risk |

| 4 | Age group (18-30 vs 31-45), sex | Telomere length shorter in MI patients aged 31-45 vs controls (P < 0.05); females with MI had shorter telomeres than female controls (P < 0.01) | No longitudinal MI risk data; small sample; case-control design |

| 5 | SES and depression combined | HR = 1.47 (1.36-1.60) for low SES + depression vs high SES, no depression (AMI risk) | Large population; no stratification < 40; depression by ICD codes; median 11.6 years follow-up |

| 6 | Time (≤ 1 year vs > 1 year), OSA status | HR for MACCE after 1 year in OSA: 3.87 (1.20-12.46); overall HR = 1.55 (0.94-2.57) for OSA vs non-OSA | Mean age 575; not exclusive to young adults; median 1-year follow-up |

| 7 | Sex (women vs men) | Adjusted OR for depressive symptoms at AMI: 1.64 (1.36-1.98) women vs men | Data collected at AMI admission only; no MI risk prediction; age up to 55; no follow-up |

| 8 | BMI (< 25 vs ≥ 25), hypertension status | Stronger inverse association of mediterranean diet with AMI in BMI < 25 and normotensive individuals | Case-control; median age 61; not restricted to young adults; no follow-up |

| 9 | Education level, sex | Men with high education had higher type A and work strain; women with low education had more type A behavior | Small sample; only men in main analysis; older data; case-control; no follow-up |

| 10 | Sleep duration categories (≤ 6 hours, 7 hours, 8 hours, ≥ 9 hours) | OR = 1.38 (1.15-1.67) for short sleep (≤ 6 hours) and non-ideal CVH | Cross-sectional; broad age range; outcome is CV health, not MI; no follow-up |

| 11 | Age (per year increase), high-risk subgroup vs low-risk | OR = 1.125 (1.063-1.190) per year age for high-growth atherosclerosis group | Cross-sectional autopsy study; subclinical outcome; no direct MI data; no follow-up |

| 12 | Sex, AMI subtype (type 1 vs others) | Women: Depression OR = 3.09 (2.37-4.04), men OR = 1.77 (1.15-2.73); family history stronger in men | Case-control; age 18-55; no exclusive < 40 data; robust adjustment; no follow-up |

| 13 | Sex | Non-traditional RFs rare (e.g., hypothyroidism, CTD, SCAD); no significant sex differences | Retrospective; in-hospital outcomes only; no effect estimates for non-traditional RFs; no follow-up |

A summary of risk of bias assessments, including individual scores, quality classification, and key limitations for each study, is provided in Table 5. The risk of bias for all 13 included studies was assessed using the NOS for cohort and case-control studies and the AHRQ tool for cross-sectional studies. Most studies were rated as moderate-to-high quality (NOS score ≥ 5 or AHRQ score ≥ 7), supporting the overall reliability of the evidence. However, common limitations included residual confounding, retrospective data collection, and incomplete adjustment for potential confounders. Several studies also had limitations related to exposure measurement or lack of stratified data for younger age groups.

| Study ID | Study design | Quality tool | Score | Quality classification | Key limitations |

| 1 | Cohort | NOS | 7 | High | Administrative data, coding errors |

| 2 | Cohort | NOS | 7 | High | Residual confounding, observational design |

| 3 | Cohort | NOS | 6 | Moderate | Retrospective data, potential selection bias |

| 4 | Case-control | NOS | 5 | Moderate | Small sample size, cross-sectional design |

| 5 | Cohort | NOS | 8 | High | Limited exposure detail |

| 6 | Cohort | NOS | 7 | High | Short follow-up, single center |

| 7 | Cohort | NOS | 7 | High | Potential residual confounding |

| 8 | Case-control | NOS | 6 | Moderate | Recall bias, dietary assessment |

| 9 | Case-control | NOS | 5 | Moderate | Small sample, self-reported exposures |

| 10 | Cross-sectional | AHRQ | 7 | Moderate | Self-report, cross-sectional design |

| 11 | Cross-sectional | AHRQ | 6 | Moderate | Surrogate outcome, autopsy data |

| 12 | Case-control | NOS | 7 | High | Potential selection bias |

| 13 | Cohort | NOS | 5 | Moderate | Retrospective design, limited non-traditional risk data |

This systematic review emphasizes on the increasing importance of non-traditional risk factors in the pathogenesis of MI under the age of 40 years. While the increase in many classic risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and dyslipidemia, has led to increased rates of premature CAD, a significant proportion of young MI patients present with other risk factors or additional risk factors[15,28]. Of great note, recent large registries such as YOUNG-MI are reporting that 10%-20% of young MI patients lack standard modifiable risk factors, and thus the need to identify emerging con

Psychosocial factors such as depression, stress, social isolation, and low SES were identified as major non-traditional risk factors in young MI patients[19,24,29]. Several studies such as the VIRGO and YOUNG-MI registry cohort groups found that depression is very common in young MI patients, especially among women, with an adjusted odds ratio for depressive symptoms as high as between 1.6 to over 3[12,24,32]. Unpartnered status was also found to increase the risk of a poor outcome post-MI (HR = 1.3) particularly in women[19,20]. These findings are consistent with the study by the International Hearty Wellbeing Program (INTERHEART), which showed that psychosocial stress is an important risk factor for MI globally[33]. Mechanistically, psychosocial stress may induce MI through neuroendocrine activation, endothelial dysfunction and pro-inflammatory pathways[12,34]. Sex-specific analyses showed that women have a greater burden of psychosocial risk factors - resulting in greater relative risk than men[29].

Accelerated biological aging as manifested by reduced telomere length was linked to MI in young adults without traditional risk factors[21]. This finding supports the hypothesis that premature cellular senescence is a contributing factor for early atherosclerosis and MI[35]. Although limited by small sample size and the cross-sectional design, these results are consistent with larger evidence for a role for telomere attrition in cardiovascular risk. Recent reviews also strongly emphasize the emerging role of biomarkers such as lipoprotein(a), although there is currently some incon

Autoimmune diseases, such as SLE and HIV infection were strongly linked to the risk of MI in young adults[15]. Chronic systemic inflammation and immune dysregulation in these conditions increase the rate of atherosclerosis and thrombosis[39,40]. The inverse association shown with RA in one study may be related to treatment or to bias in surveillance and needs further study[18]. These findings highlight the importance of cardiovascular risk assessment and management in the young patient with autoimmune disease[16].

OSA was linked with a nearly 4-fold higher risk of major adverse cardiovascular events after 1 year in young patients with acute coronary syndrome[23]. Mechanisms can include intermittent hypoxia and sympathetic activation[41]. Short sleep duration was also associated with impaired CVD health parameters such as hypertension and dysglycemia, al

In various articles, the link between psychosocial stress, depression and MI was independent, especially with regard to women[24,29]. Inflammatory and autoimmune markers also displayed strong associations but the strength of effect varied[18]. Evidence for environmental and lifestyle factors was quite supportive but sometimes limited by study design or outcome definitions[23,27]. Limitations of included studies include heterogeneity in terms of design, exposure definitions and age ranges, with some studies including adults up to 55 years[28]. Many used cross sectional or administrative data which may cause bias and limit causal inference[17]. Little longitudinal data and stratified analyses for adults strictly under 40 were limited. Small sample sizes and the reliance of International Classification of Diseases coding in some cohorts may further limit the generalizability.

These findings have important clinical implications to risk assessment and prevention on young adults. Current risk models, like the ones suggested by the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, do not adequately take into account non-traditional risk factors[16]. Incorporation of factors related to the psyche, autoimmunity and lifestyle into risk prediction tools could lead to better identification of high-risk individuals in early stages[31,33]. We recommend development and validation of a non-traditional risk score prototype specific to young adults, which may be used to devise targeted preventive strategies and interventions.

Future research efforts should focus on prospective cohort studies in adults under 40 characterized in detail about psychosocial, biological, autoimmune, and environmental exposures. Integration of novel biomarkers, genetics information and sex-specific studies will improve the risk stratification. Interventional studies addressing modifiable, non-traditional risk factors, including depression, sleep disorders and environmental exposures, are warranted to assess their effectiveness on MI prevention and outcomes in the population.

This systematic review shows that non-traditional risk factors such as psychosocial stressors, autoimmune disorders, biological aging and specific lifestyle and environmental exposures play a significant role in MI risk and outcome among individuals aged < 40 years. Psychosocial factors like depression, low SES and unpartnered status were significantly associated with adverse events, especially among young women. Autoimmune diseases and inflammation indicators, as well as sleep disorders and unhealthy lifestyle patterns, additionally improved the risk. The evidence highlights considerable heterogeneity in the risk profiles and important sex differences. However, the current literature has limitations such as variations in study design, age stratification, and no longitudinal data. Moving forward, adding non-traditional risk factors to clinical risk assessment and prevention strategies is important in early identification and better mana

| 1. | Vaduganathan M, Mensah GA, Turco JV, Fuster V, Roth GA. The Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk: A Compass for Future Health. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;80:2361-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1319] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Collet C, Onuma Y, Andreini D, Sonck J, Pompilio G, Mushtaq S, La Meir M, Miyazaki Y, de Mey J, Gaemperli O, Ouda A, Maureira JP, Mandry D, Camenzind E, Macron L, Doenst T, Teichgräber U, Sigusch H, Asano T, Katagiri Y, Morel MA, Lindeboom W, Pontone G, Lüscher TF, Bartorelli AL, Serruys PW. Coronary computed tomography angiography for heart team decision-making in multivessel coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:3689-3698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Arora S, Stouffer GA, Kucharska-Newton AM, Qamar A, Vaduganathan M, Pandey A, Porterfield D, Blankstein R, Rosamond WD, Bhatt DL, Caughey MC. Twenty Year Trends and Sex Differences in Young Adults Hospitalized With Acute Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2019;139:1047-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 544] [Article Influence: 77.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Singh A, Gupta A, DeFilippis EM, Qamar A, Biery DW, Almarzooq Z, Collins B, Fatima A, Jackson C, Galazka P, Ramsis M, Pipilas DC, Divakaran S, Cawley M, Hainer J, Klein J, Jarolim P, Nasir K, Januzzi JL, Di Carli MF, Bhatt DL, Blankstein R. Cardiovascular Mortality After Type 1 and Type 2 Myocardial Infarction in Young Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1003-1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Butler J, Hammonds K, Talha KM, Alhamdow A, Bennett MM, Bomar JVA, Ettlinger JA, Traba MM, Priest EL, Schmedt N, Zeballos C, Shaver CN, Afzal A, Widmer RJ, Gottlieb RL, Mack MJ, Packer M. Incident heart failure and recurrent coronary events following acute myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2025;46:1540-1550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sofogianni A, Stalikas N, Antza C, Tziomalos K. Cardiovascular Risk Prediction Models and Scores in the Era of Personalized Medicine. J Pers Med. 2022;12:1180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moshkani Farahani M, Ghiasi SMS, Karamali M, Golchin Vafa R. Evaluating Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among Healthcare Professionals in Iran. Med Sci Monit. 2025;31:e947409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wang L, Lei J, Wang R, Li K. Non-Traditional Risk Factors as Contributors to Cardiovascular Disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2023;24:134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gupta A, Wang Y, Spertus JA, Geda M, Lorenze N, Nkonde-Price C, D'Onofrio G, Lichtman JH, Krumholz HM. Trends in acute myocardial infarction in young patients and differences by sex and race, 2001 to 2010. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:337-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 285] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sepehrinia M, Pourmontaseri H, Sayadi M, Naghizadeh MM, Homayounfar R, Farjam M, Dehghan A, Alkamel A. Comparison of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and Framingham risk scores (FRS) in an Iranian population. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Risk Prev. 2024;21:200287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | DeFilippis EM, Singh A, Divakaran S, Gupta A, Collins BL, Biery D, Qamar A, Fatima A, Ramsis M, Pipilas D, Rajabi R, Eng M, Hainer J, Klein J, Januzzi JL, Nasir K, Di Carli MF, Bhatt DL, Blankstein R. Cocaine and Marijuana Use Among Young Adults With Myocardial Infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71:2540-2551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rosengren A, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Sliwa K, Zubaid M, Almahmeed WA, Blackett KN, Sitthi-amorn C, Sato H, Yusuf S; INTERHEART investigators. Association of psychosocial risk factors with risk of acute myocardial infarction in 11119 cases and 13648 controls from 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:953-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1484] [Cited by in RCA: 1501] [Article Influence: 68.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Choudhury L, Marsh JD. Myocardial infarction in young patients. Am J Med. 1999;107:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bucholz EM, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Lindau ST, D'Onofrio G, Geda M, Spatz ES, Beltrame JF, Lichtman JH, Lorenze NP, Bueno H, Krumholz HM. Editor's Choice-Sex differences in young patients with acute myocardial infarction: A VIRGO study analysis. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2017;6:610-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Krittanawong C, Khawaja M, Tamis-Holland JE, Girotra S, Rao SV. Acute Myocardial Infarction: Etiologies and Mimickers in Young Patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2023;12:e029971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC Jr, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 1288] [Article Influence: 161.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 52244] [Article Influence: 10448.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Krittanawong C, Liu Y, Mahtta D, Narasimhan B, Wang Z, Jneid H, Tamis-Holland JE, Mahboob A, Baber U, Mehran R, Wilson Tang WH, Ballantyne CM, Virani SS. Non-traditional risk factors and the risk of myocardial infarction in the young in the US population-based cohort. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;30:100634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhu C, Dreyer RP, Li F, Spatz ES, Caraballo C, Mahajan S, Raparelli V, Leifheit EC, Lu Y, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA, D'Onofrio G, Pilote L, Lichtman JH. Association of marital/partner status with hospital readmission among young adults with acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0287949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dreyer RP, Raparelli V, Tsang SW, D'Onofrio G, Lorenze N, Xie CF, Geda M, Pilote L, Murphy TE. Development and Validation of a Risk Prediction Model for 1-Year Readmission Among Young Adults Hospitalized for Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e021047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gupta MD, Miglani M, Bansal A, Jain V, Arora S, Kumar S, Virani SS, Kalra A, Yadav R, Pasha Q, Yusuf J, Mukhopadhyay S, Tyagi S, Girish MP. Telomere length in young patients with acute myocardial infarction without conventional risk factors: A pilot study from a South Asian population. Indian Heart J. 2020;72:619-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Cho Y, Lim TH, Kang H, Lee Y, Lee H, Kim H. Socioeconomic status and depression as combined risk factors for acute myocardial infarction and stroke: A population-based study of 2.7 million Korean adults. J Psychosom Res. 2019;121:14-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fan J, Wang X, Ma X, Somers VK, Nie S, Wei Y. Association of Obstructive Sleep Apnea With Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e010826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Smolderen KG, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, D'Onofrio G, Zhou S, Lichtman JH, Geda M, Bueno H, Beltrame J, Safdar B, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA. Depressive symptoms in younger women and men with acute myocardial infarction: insights from the VIRGO study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4:e001424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Turati F, Pelucchi C, Galeone C, Praud D, Tavani A, La Vecchia C. Mediterranean diet and non-fatal acute myocardial infarction: a case-control study from Italy. Public Health Nutr. 2015;18:713-720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Orth-Gomér K, Hamsten A, Perski A, Theorell T, de Faire U. Type A behaviour, education and psychosocial work characteristics in relation to ischemic heart disease--a case control study of young survivors of myocardial infarction. J Psychosom Res. 1986;30:633-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zhao M, Chen T, Huang C, Zhong Q. Association between sleep duration and ideal cardiovascular health in Chinese adults: results from the China health and nutrition survey. Fam Pract. 2023;40:314-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Head T, Henn L, Andreev VP, Herderick EE, Deo SK, Daunert S, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ. Accelerated coronary atherosclerosis not explained by traditional risk factors in 13% of young individuals. Am Heart J. 2019;208:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lu Y, Li SX, Liu Y, Rodriguez F, Watson KE, Dreyer RP, Khera R, Murugiah K, D'Onofrio G, Spatz ES, Nasir K, Masoudi FA, Krumholz HM. Sex-Specific Risk Factors Associated With First Acute Myocardial Infarction in Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e229953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jariwala P, Padmavathi A, Patil R, Chawla K, Jadhav K. The prevalence of risk factors and pattern of obstructive coronary artery disease in young Indians (< 45 years) undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: A gender-based multi-center study. Indian Heart J. 2022;74:282-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Singh A, Collins B, Qamar A, Gupta A, Fatima A, Divakaran S, Klein J, Hainer J, Jarolim P, Shah RV, Nasir K, Di Carli MF, Bhatt DL, Blankstein R. Study of young patients with myocardial infarction: Design and rationale of the YOUNG-MI Registry. Clin Cardiol. 2017;40:955-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | DeFilippis EM, Collins BL, Singh A, Biery DW, Fatima A, Qamar A, Berman AN, Gupta A, Cawley M, Wood MJ, Klein J, Hainer J, Gulati M, Taqueti VR, Di Carli MF, Nasir K, Bhatt DL, Blankstein R. Women who experience a myocardial infarction at a young age have worse outcomes compared with men: the Mass General Brigham YOUNG-MI registry. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:4127-4137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, McQueen M, Budaj A, Pais P, Varigos J, Lisheng L; INTERHEART Study Investigators. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7301] [Cited by in RCA: 7609] [Article Influence: 345.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Santosa A, Rosengren A, Ramasundarahettige C, Rangarajan S, Gulec S, Chifamba J, Lear SA, Poirier P, Yeates KE, Yusuf R, Orlandini A, Weida L, Sidong L, Yibing Z, Mohan V, Kaur M, Zatonska K, Ismail N, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Iqbal R, Palileo-Villanueva LM, Yusufali AH, AlHabib KF, Yusuf S. Psychosocial Risk Factors and Cardiovascular Disease and Death in a Population-Based Cohort From 21 Low-, Middle-, and High-Income Countries. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2138920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Haycock PC, Heydon EE, Kaptoge S, Butterworth AS, Thompson A, Willeit P. Leucocyte telomere length and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g4227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 716] [Cited by in RCA: 679] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kozarova M, Lackova A, Kozelova Z, Tomco L. Lipoprotein (a): A Novel Cardiovascular Risk Factor. Balkan Med J. 2023;40:234-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Faresjö Å, Theodorsson E, Stomby A, Quist H, Jones MP, Östgren CJ, Dahlqvist P, Faresjö T. Higher hair cortisol levels associated with previous cardiovascular events and cardiovascular risks in a large cross-sectional population study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24:536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Iob E, Steptoe A. Cardiovascular Disease and Hair Cortisol: a Novel Biomarker of Chronic Stress. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2019;21:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Manzi S, Meilahn EN, Rairie JE, Conte CG, Medsger TA Jr, Jansen-McWilliams L, D'Agostino RB, Kuller LH. Age-specific incidence rates of myocardial infarction and angina in women with systemic lupus erythematosus: comparison with the Framingham Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1280] [Cited by in RCA: 1283] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1685-1695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6103] [Cited by in RCA: 6466] [Article Influence: 307.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, Daniels S, Floras JS, Hunt CE, Olson LJ, Pickering TG, Russell R, Woo M, Young T; American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Stroke Council; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; American College of Cardiology Foundation. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/american College Of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council On Cardiovascular Nursing. In collaboration with the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute National Center on Sleep Disorders Research (National Institutes of Health). Circulation. 2008;118:1080-1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 287] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Xie Y, Xu E, Bowe B, Al-Aly Z. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2022;28:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1452] [Cited by in RCA: 1319] [Article Influence: 329.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Rajagopalan S, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD. Air Pollution and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:2054-2070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 844] [Article Influence: 120.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/