Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.114108

Revised: October 11, 2025

Accepted: December 1, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 125 Days and 5.6 Hours

Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) is a significant factor that negatively impacts the treatment outcomes of coronary heart disease, particularly acute myo

To explore the effects and mechanisms of NAD+ on cell death caused by hypo

Cell viability was assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 assay. Apoptosis in H9c2 cells was evaluated through terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deo

The study demonstrated that NAD+ supplementation protects H9c2 cells from H/R induced cell pyroptosis. Me

These results indicate that NAD+ supplementation may serve as a promising therapeutic strategy for I/R injury.

Core Tip: Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) was a hazardous factor affecting the therapeutic effects of coronary heart disease, especially acute myocardial infarction. The oxidized form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD)-NAD+ is crucial for various cellular functions. This study explored the effects and underlying mechanisms of NAD+ on cell death caused by I/R injury in H9c2 cells. The results showed that supplementing with NAD+ can protect H9c2 cells from pyroptosis induced by I/R injury. Mechanistically, NAD+ supplementation reduces pyroptosis in H9c2 cells triggered by hypoxia/re-oxygenation by inhibiting the activation of the NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome. These results indicate that NAD+ supplementation could be a promising therapeutic strategy for I/R injury.

- Citation: Dong S, Liu YQ, Tu YJ, Gao S, Liu YJ, Liu C, Pei ZW. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide inhibits the production of reactive oxygen species and myocardial cell pyroptosis caused by hypoxia/re-oxygenation injury. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 114108

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/114108.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.114108

Acute and ongoing myocardial ischemia, caused by blockage of coronary blood flow, leads to the irreversible death of heart muscle cells (cardiomyocytes) and impaired heart function. The most effective approach to saving these dying cells has been immediate reperfusion therapy[1]. However, quickly restoring oxygen supply after ischemia can cause further damage and worsen heart dysfunction, a phenomenon known as myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury[2]. Ischemia alone can damage the endothelium and smooth muscle, while reperfusion may cause microvascular injury, complicating the restoration of normal coronary blood flow[2]. Myocardial I/R is a significant factor that negatively impacts treatment outcomes in coronary heart disease, especially in acute myocardial infarction.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly reactive oxygen-containing molecules with at least one oxygen atom and one or more unpaired electrons, allowing them to exist independently[3]. Their increased electron content makes them highly reactive and prone to participate in one-electron oxidative transfer reactions that modify or damage macromolecules[4]. ROS play a crucial role in myocardial I/R injury by oxidizing cellular components and activating key proteolytic enzymes[5]. During ischemia, ROS levels are low but rise sharply during reperfusion due to the return of oxygen[6]. Excessive ROS can cause widespread oxidative damage to cardiomyocytes, leading to loss of cell viability and myocardial stunning[7]. Studies have shown that treatment with antioxidants or ROS scavengers significantly reduces infarct size and lessens cardiomyocyte injury caused by I/R[8]. Importantly, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (reduced form) oxidase (NOX) is the primary enzymatic source of ROS in the cardiovascular system. ROS interacts with mitochondria can further increase ROS production and impair mitochondrial function by inducing pro-apoptotic Bcl2 protein expression and cytochrome c release[9]. Inhibiting ROS production with NOX inhibitors or scavenging ROS with agents like N-acetylcysteine can reduce apoptosis and improve cell survival[10]. NAD+, the oxidized form of NAD, a widespread pyridine nucleotide, is vital for numerous cellular functions, including metabolism, adenosine triphosphate generation, and DNA repair. Adequate NAD+ levels help cells adapt to metabolic stress and maintain genomic stability, mito

The NOD-like receptor pyrin domain-containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome is a multi-protein complex that, upon activation, binds directly to the adaptor protein apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD (ASC) and subsequently activates precursor caspase-1 (pro-caspase-1), forming the NLRP3 inflammasome[13]. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a large multi-protein complex. When activated, NLRP3 directly interacts with the adaptor protein ASC, which then activates the precursor form of caspase-1 (pro-caspase-1) to assemble the NLRP3 inflammasome[13]. This inflammasome converts pro-caspase-1 into its active cleaved form (cleaved-caspase-1), which in turn cleaves pro-interleukin (IL)-1β into its active form IL-1β (cleaved-IL-1β). This process also triggers the release of gasdermin D, which forms pores in the cell membrane and induces pyroptosis[14].

ROS can promote inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome[15]. It has been shown that pyroptosis driven by NLRP3 activation contributes to the worsening of myocardial I/R injury[16]. Furthermore, previous research has indicated that inhibiting NLRP3 activation not only reduces pyroptosis but also mitigates myocardial I/R injury[17]. Therefore, targeting ROS/NLRP3-induced pyroptosis may represent a promising approach to prevent myocardial I/R injury. Moreover, the previous study reported that inhibiting NLRP3 activation not only downregulated pyroptosis but also alleviated myocardial I/R injury[18]. Therefore, manipulating ROS/NLRP3 induced pyroptosis might be a promising strategy to prevent myocardial I/R injury. In this study, we have investigated the protective effects of NAD+ supplementation on H9c2 cell pyroptosis induced by myocardial I/R injury. In addition, the role of ROS and the NLRP3 inflammasome in myocardial I/R injury was also determined.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, United States), unless otherwise specified. NAD+ (HY-B0445, MedChemExpress, NJ, United States) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered solution (PBS; KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China) to prepare a 100 mmol/L stock solution. Acetylcysteine (HY-B0215, MedChemExpress, NJ, United States), used as a ROS inhibitor, was dissolved in PBS to make 10 mmol/L stock solution.

H9c2 cells (RRID: CVCL_0286) were obtained from Procell Life Sciences & Technology (Wuhan, China). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10270106, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, United States), and incubated in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells were sub-cultured once they reached 80% confluence.

Regarding the hypoxia/re-oxygenation (H/R) culture procedure, once the cells reached 70% confluence, the DMEM medium with fetal bovine serum was replaced with an ischemia buffer containing 10 mmol/L deoxyglucose, 137 mmol/L NaCl, 12 mmol/L KCl, 0.49 mmol/L MgCl2, 0.9 mmol/L CaCl2∙2H2O, 0.75 mmol/L sodium dithionite, 20 mmol/L lactate, and 4 mmol/L 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid at pH 6.5. This buffer was aerated with nitrogen gas to remove oxygen. H9c2 cells incubated in the buffer were then placed inside a hypoxia incubator chamber (27310, STEMCELL Technology, Vancouver, Canada), equipped with a single flow meter (27311, STEMCELL Technology, Vancouver, Canada). To eliminate oxygen from the chamber, a gas mixture of 95% nitrogen and 5% CO2 was flushed through the chamber for 20 minutes. Afterwards, the sealed and humidified chamber was incubated at 37 °C to mimic hypoxic conditions. Following 6 hours of hypoxia, reoxygenation treatment was applied for 6 hours, which involved replacing the ischemia buffer with fresh culture medium, taking the cells out from the hypoxia incubator chamber, and incubating them at 37 °C with 5% CO2. For the treatment with NAD+ or acetylcysteine, 1 mmol/L of either NAD+ or acetylcysteine was included in the ischemia buffer throughout the 6-hour hypoxia duration to suppress ROS generation.

The viability of H9c2 cells was measured using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (KGA9305-500, KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China). Briefly, 5000 cells were plated into each well of 96-well plates, and cultured for 24 hours. Following this, the cells underwent H/R treatment, either with or without the addition of NAD+ or acetylcysteine. Cells cultured in the incubator containing 21% oxygen and 5% CO2 served as the control group. Following these treatments, the culture medium was removed, and the cells were rinsed once with PBS. Then, 200 μL of fresh medium containing 10% Cell Counting Kit-8 solution was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 2 hours. Subsequently, 200 μL of the supernatant from each well was transferred to a new 96-well plate, and the optical density at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Infinite M Nano, Tecan, Switzerland). Cell viability was evaluated through three independent experiments.

H9c2 cells were seeded at a density of 10000 cells per glass-bottom petri dish (FCFC016, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), and cultured for 24 hours. Following H/R treatment, with or without NAD+ or acetylcysteine, the cells were incubated for 30 minutes in a live/dead staining solution containing 2 μM calcein acetoxymethyl ester and 4 μM ethidium homodimer-1 (L3224, Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States), at room temperature in the dark. After rinsing twice with PBS, the cells were examined, and images were captured using confocal laser scanning microscopy (DMi8, Leica, Heidelberg, Germany).

Apoptotic death of H9c2 cells was determined using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxyuridine triphosphate nick end labeling (TUNEL) with a one-step TUNEL apoptosis assay kit (C1088, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, the cells were seeded at 10000 cells per glass-bottom petri dish and cultured for 24 hours, then subjected to H/R treatment with or without NAD+ or acetylcysteine. After rinsing twice with PBS, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States) for 30 minutes at room tempera

The level of intracellular ROS was measured using the fluorescent probe dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate (Reactive Oxygen Species Assay Kit, S0033S, Beyotime, Shanghai, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. In brief, following different treatments, cells grown in glass-bottom petri dishes were incubated with 10 μM of dichloro-dihydrofluorescein diacetate at 37 °C for 20 minutes in the dark, followed by three washes with DMEM medium. Fluorescence images indicating intracellular ROS were obtained using confocal laser scanning microscopy.

The intracellular level of NAD was determined with a NAD/NADH quantification kit (MAK037, Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, after various treatments, cells were rinsed with cold PBS. For each assay, 2 × 105 cells were pelleted in a microcentrifuge tube by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 minutes. Cells were then extracted by homogenizing them on ice in 400 μL of the NADH/NAD extraction buffer. Samples were vortexed for 10 seconds and centrifuged at 13000 × g for 10 minutes. The supernatant containing extracted NAD/NADH was transferred to a labeled tube. To measure total cellular NAD (both NADH and NAD+), up to 50 μL of the extracted samples were loaded into a 96-well plate. Then, 100 μL of the master reaction mix was added, mixed thoroughly using a horizontal shaker, and incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes to convert NAD to NADH. Next, 10 μL of the NADH developer was added to each well, and the plate was incubated at room temperature for 3 hours. The reactions were stopped by adding 10 μL of stop solution into each well and mixing well.

For NADH measurement alone, 200 μL of the extracted samples were placed into a microcentrifuge tube and heated at 60 °C for 30 minutes in a water bath to degrade NAD+. Afterwards, the samples were cooled on ice. Concentrations of total NAD and NADH were determined based on a NADH standard curve. The NAD+/NADH ratio in each sample was calculated using the following formula: Ratio = (NADtotal - NADH)/NADH. NADtotal = amount of total NAD (NAD+ + NADH) in unknown sample (pmol) from standard curve. NADH = amount of NADH in unknown sample (pmol) from standard curve.

A two-step reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction method was applied to examine the relative expression levels of the genes, with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase serving as an internal reference. Total RNA was extracted from cells using SevenFast®Total RNA extraction kit for cells (SM130, Seven Biotech, Beijing, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Reverse transcription was performed using a PrimeScript reverse transcription reagent kit (RR036A, TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan). Real-time polymerase chain reaction amplification was carried out with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Perfect Real Time; RR820A, Takara, Shiga, Japan). Polymerase chain reaction amplification and fluorescence detection were performed using the Applied Biosystems™ 7500 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, United States). The primers in this study were designed and synthesized by Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, United States), and the primer sequences were listed in Table 1. The results were expressed as relative expression levels of the target genes compared to the control group, calculated using the Ct method (2-∆∆Ct).

| Gene | Sense (5’-3’) | Anti-sense (5’-3’) |

| GAPDH | AAGAAACCCTGGACCACCCAGC | TGGTATTCGAGAGAAGGGAGGG |

| NLRP3 | AGGACCCACAGTGTAACTTGCA | GCTTGAGTCCCATGTCTCCAA |

| ASC | GGCAATGTGCTGACTGAAGGA | GTAGGGCTGTGTTTGCCTCAA |

| Caspase-1 | TGCCCAGAGCACAAGACTTCT | GCACTTCAATGTGTTCATCATTTG |

Cells were lysed in a lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (KGB5303, KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China). Protein concentration was measured using the BCA protein assay kit (KGB2101, KeyGEN BioTECH, Nanjing, China), and an equal amount of protein was loaded in each lane. Constant voltage electrophoresis was carried out with 10% polyacrylamide gels (SW143-02, Seven Biotech, Beijing, China). Proteins were then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (IPVH00010, Merck, MA, United States). These membranes were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, United States), incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies: Anti-ASC (1:200; sc-514414, Santa Cruz, TX, United States), anti-cryopyrin (1:200; sc-134306, Santa Cruz, TX, United States), anti-caspase-1 (1:200; sc-56036, Santa Cruz, TX, United States), anti-caspase1/P20 (1:2000; 22915-1-AP, Proteintech, Wuhan, China), and anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (1:500; sc-365062, Santa Cruz, TX, United States). After being washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), the polyvinylidene fluoride membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (heavy chain + light chain) antibody (1:10000; SA00012-2, Proteintech, IL, United States) or horseradish peroxidase -conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (heavy chain + light chain; 1:5000; SA00001-2, Proteintech, IL, United States), at room temperature for 90 minutes, followed by another washing with Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20. The enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Seven Biotech, Beijing, China) was used to visualize the protein images.

Each experiment was performed at least three times. The data were presented as means ± SD. ANOVA and Tukey’s test were used to examine the differences among groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

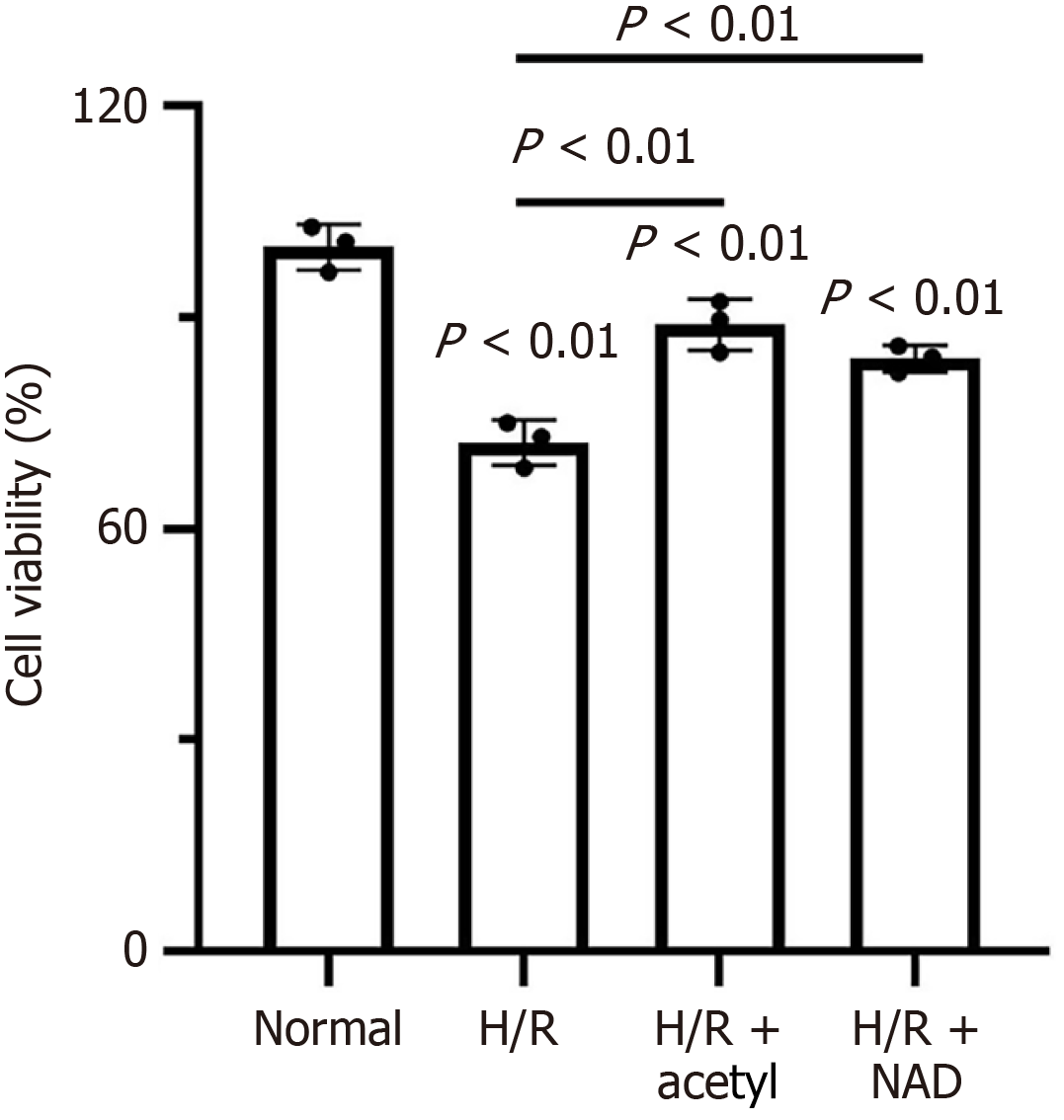

To investigate the effect of NAD+ on cellular activity, H9c2 cells were subjected to H/R treatments, with either 1 mmol/L acetylcysteine, or 1 mmol/L NAD+. As shown in Figure 1, the cell viability in the H/R group was significantly lower than that in the normal group (control group). Both acetylcysteine and NAD+ treatments during H/R significantly improved cell viability, compared to the H/R group alone. Although acetylcysteine had a slightly stronger effect than NAD+, the difference was not statistically significant. Furthermore, the live/dead staining revealed almost no dead cells in the control group, whereas the H/R group exhibited a significantly higher number of dead cells (Figure 2A). Treatment with acetylcysteine or NAD+ significantly increased the number of living cells, compared to the H/R group (Figure 2A). Consistent with the live/dead staining results, the TUNEL assay demonstrated that apoptotic cell death was higher following H/R treatment, compared to the control group (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 1). Notably, apoptosis was significantly reduced by both acetylcysteine and NAD+ treatments (Figure 2B and Supplementary Figure 1).

To investigate whether the cell death caused by H/R stimulation was attributed to oxidative damage, the levels of intracellular ROS in H9c2 cells were measured. The results showed that ROS production increased after H/R stimulation, compared to the control group. Both acetylcysteine and NAD+ significantly reduced ROS generation in H9c2 cells following H/R stimulation (Figure 2C).

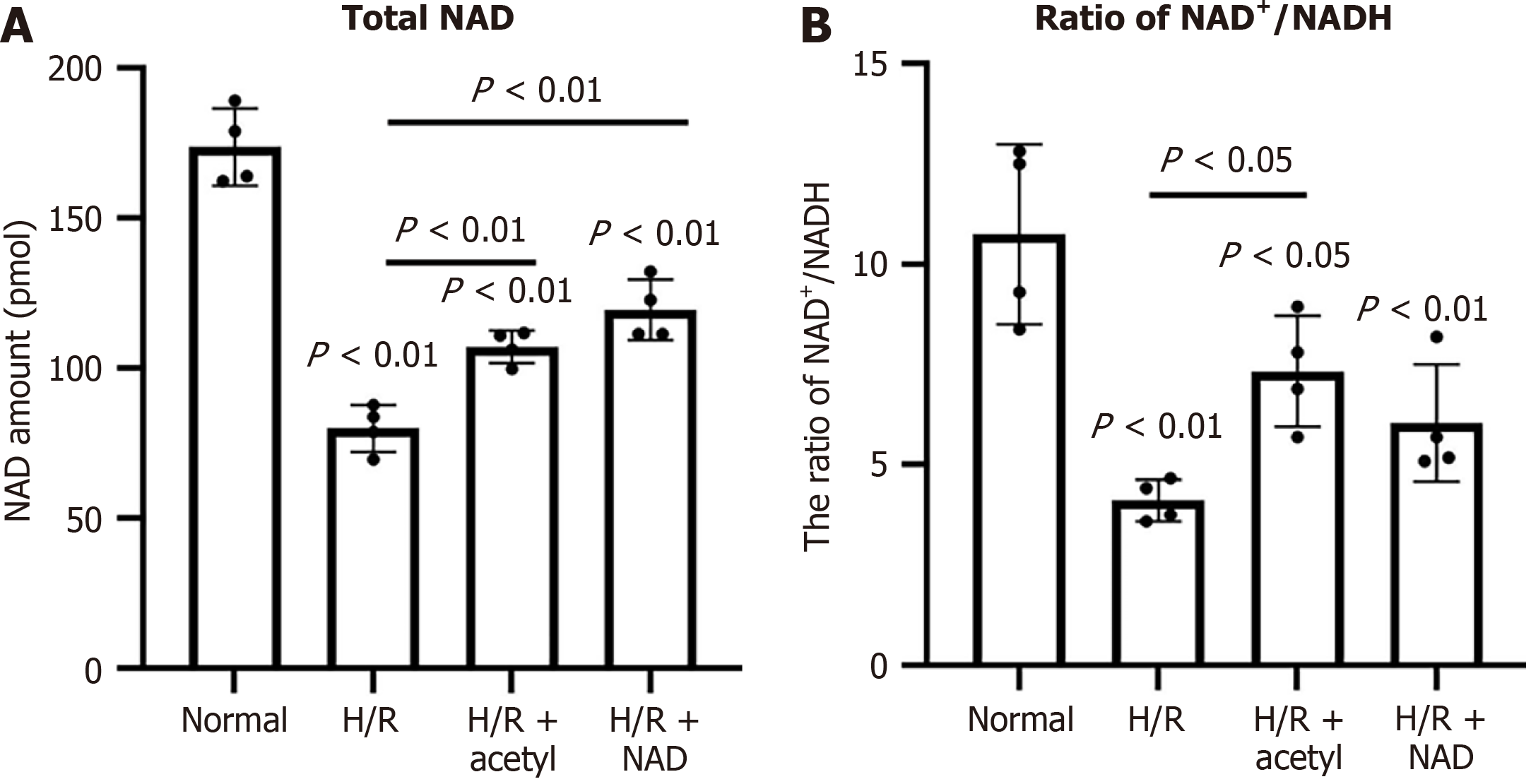

After H/R stimulation, the total NAD content in H9c2 cells decreased significantly compared to the normal group, from 173.58 ± 11.08 pmol to 79.92 ± 7.81 pmol (Figure 3A). Similarly, the NAD+/NADH ratio decreased markedly, from 10.7 ± 0.2 to 4.2 ± 0.9 (Figure 3B). Supplementing with external NAD+ significantly elevated the intracellular NAD concentration, from 79.92 ± 7.81 pmol to 119.55 ± 10.03 pmol, compared to the H/R group (Figure 3A). The NAD+/NADH ratio increased to 5.93 ± 0.44 following treatment with external NAD+, but this change was not significantly different compared to the H/R group (Figure 3B).

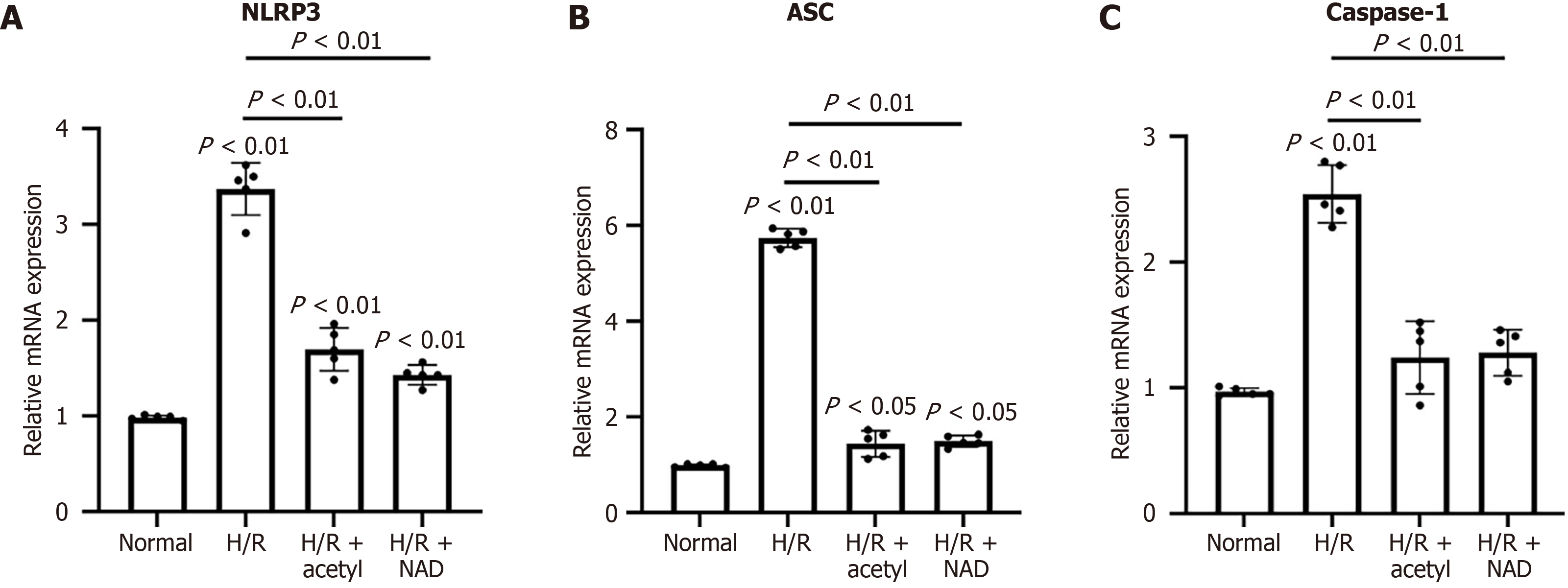

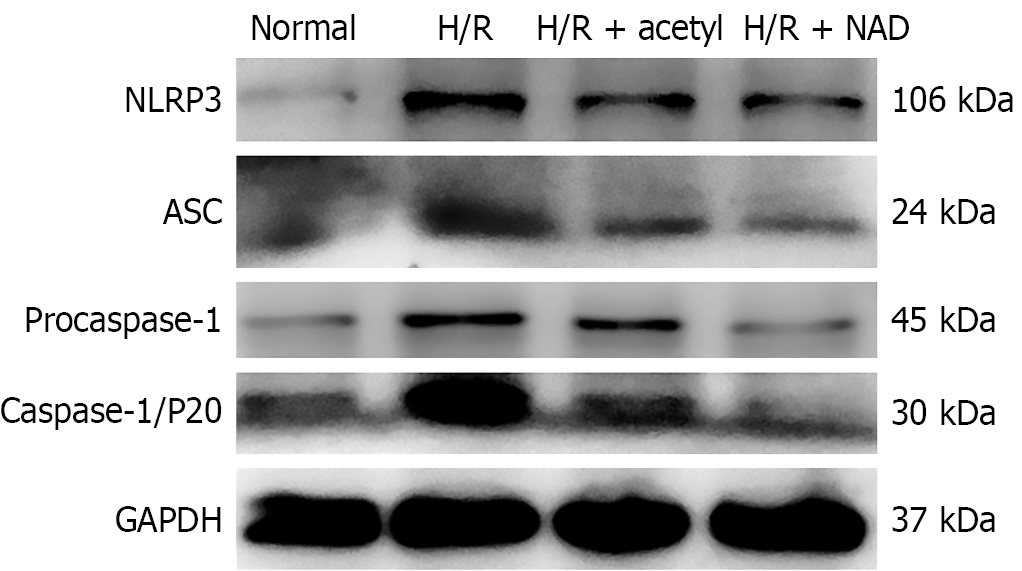

H/R stimulation triggered the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome by elevating the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, at both the mRNA and protein levels, compared to the control group (Figures 4 and 5). Additionally, treatment with acetylcysteine or NAD+ significantly reduced the mRNA levels of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, compared to the H/R group (Figure 4). Furthermore, after H/R stimulation, the levels of NLRP3, ASC, and procaspase-1 proteins were elevated, compared to the control group (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 2). Both acetylcysteine and NAD+ were able to suppress the expression levels of NLRP3, ASC, and procaspase-1 (Figure 5 and Supplementary Figure 2).

This research has shown that supplementing with external NAD+ provides significant protection against cell death in H9c2 cells caused by H/R stress. Additionally, the study explored the potential mechanism underlying the protective effects of NAD+. The findings suggested that exogenous NAD+ supplementation reduced H9c2 cell pyroptosis caused by H/R, by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation. The NLRP3 inflammasome is a NOD-like receptor, consisting of NLRP3, ASC, and procaspase-1. It can recognize diverse stimuli, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns, leading to the activation of procaspase-1 into its active form, caspase-1. ROS, particularly those originating from mitochondria, are one of the critical mediators of NLRP3 inflammasome activation[18]. Moreover, ROS have been identified as an important NLRP3 inflammasome activator in cardiac diseases. Previous studies have shown that ROS activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, which then triggers caspase-1-dependent pyroptosis[19]. The ROS inhibitor has been found to decrease NLRP3 mRNA level, indicating that ROS play a crucial role in regulating NLRP3 gene expression[14].

In this study, we observed that H9c2 cells subjected to H/R stimulation produced higher levels of ROS, compared to cells maintained under normal conditions. Correspondingly, NLRP3 expression was significantly increased in these cells. Treatment with the ROS inhibitor acetylcysteine reduced NLRP3 gene expression. These findings were in accordance with previous studies[14,18]. NAD+ refers to the oxidized form of NAD, and NADH is its reduced form. NAD+ replenishment has been shown to reduce various I/R injuries, including those affecting the brain, kidney, liver, and spinal cord[13,14,18,20]. NAD+ plays a crucial role in several key processes related to cardiovascular disease[21], and has demonstrated significant protective effects against myocardial I/R injury[8,10,21]. Zhang et al[8] demonstrated that administration of NAD+ could dose-dependently decrease I/R induced myocardial infarct size, reduce the apoptotic damage in the heart, and lower TUNEL signals following I/R injury. Liu et al[22] discovered that exogenous NAD administration promoted NAD-dependent protein deacylase sirtuin-5-mediated succinate dehydrogenase subunit A desuccinylation, which reduced succinate dehydrogenase subunit A activity and subsequently decreased ROS production.

In the present study, both NAD+ and the ROS inhibitor acetylcysteine similarly reduced H9c2 cell death, lowered ROS levels, and down-regulated the expression of NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1 after H/R stimulation. These findings suggested that NAD+ may inhibit NLRP3 inflammasome activation by reducing ROS generation. The study also measured intracellular NAD+ levels and the NAD+/NADH ratio to confirm that exogenous NAD+ was taken up by H9c2 cells. Maintaining the NAD+/NADH ratio is vital for cellular redox balance. It has been shown that increasing NAD+ content decreases the NADH/NAD+ ratio and strongly suppresses ROS production[23]. Here, H9c2 cells exhibited significantly reduced intracellular NAD content and NAD+/NADH ratio following H/R stimulation, but supplementation with NAD+ significantly increased both NAD+ levels and the NAD+/NADH ratio. However, the mechanism by which extracellular NAD+ enters H9c2 cells remains unclear. Previous reports indicate that connexin-43 channels in the plasma membrane can actively transport extracellular NAD+[24], and connexin-43 has been identified as responsible for NAD+ entry into cardiomyocytes[25]. Since connexin-43 is also present in the plasma membrane of H9c2 cardiac myoblasts[26], Liu et al[22] have proposed that NAD+ enters H9c2 cells via connexin-43 channels. Mo et al[17] discovered that increased intracellular Ca2+ levels trigger H/R-induced cardiomyocyte pyroptosis through the NLRP3/caspase-1 pathway. Pyroptosis, a recently identified form of programmed necrosis[27], plays a significant role in initiating and sustaining inflammatory responses. It is characterized as a caspase-1-dependent process, with NLRP3 being essential for caspase-1 activation[28]. Inhibiting caspase-1 has been shown to alleviate human myocardial ischemic dysfunction by suppressing IL-18 and IL-1β[29]. The findings of this study also indicate that pyroptosis may be involved in the mechanism by which NAD+ inhibits H/R-induced injury in H9c2 cells.

This study suggests that NAD+ supplementation may protect H9c2 cells against I/R injury-induced pyroptosis. Nevertheless, there are still some limitations: First, different concentrations of NAD+ need to be tested to determine if its protective effect is dose-dependent, and to identify the optimal concentration for future research. Secondly, pyroptosis-related markers should be examined to verify whether pyroptosis plays a role in the protective effects of NAD+ against H/R-induced myocardial cell death. Last but not least, the mechanism by which extracellular NAD+ enters H9c2 cells should be clarified to better understand how cells utilize extracellular NAD+.

This study demonstrated that supplementing with NAD+ protected H9c2 cells from pyroptosis induced by I/R injury by suppressing the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome. These findings suggest that NAD+ supplementation could serve as a potential therapeutic approach for I/R injury.

| 1. | Ghavami S, Gupta S, Ambrose E, Hnatowich M, Freed DH, Dixon IM. Autophagy and heart disease: implications for cardiac ischemia-reperfusion damage. Curr Mol Med. 2014;14:616-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Algoet M, Janssens S, Himmelreich U, Gsell W, Pusovnik M, Van den Eynde J, Oosterlinck W. Myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury and the influence of inflammation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2023;33:357-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 109.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jakubczyk K, Dec K, Kałduńska J, Kawczuga D, Kochman J, Janda K. Reactive oxygen species - sources, functions, oxidative damage. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2020;48:124-127. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Averill-Bates D. Reactive oxygen species and cell signaling. Review. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2024;1871:119573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 76.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim S, Lee W, Jo H, Sonn SK, Jeong SJ, Seo S, Suh J, Jin J, Kweon HY, Kim TK, Moon SH, Jeon S, Kim JW, Kim YR, Lee EW, Shin HK, Park SH, Oh GT. The antioxidant enzyme Peroxiredoxin-1 controls stroke-associated microglia against acute ischemic stroke. Redox Biol. 2022;54:102347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Teodoro JS, Varela AT, Duarte FV, Gomes AP, Palmeira CM, Rolo AP. Indirubin and NAD(+) prevent mitochondrial ischaemia/reperfusion damage in fatty livers. Eur J Clin Invest. 2018;48:e12932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Metcalfe M, David BT, Langley BC, Hill CE. Elevation of NAD(+) by nicotinamide riboside spares spinal cord tissue from injury and promotes locomotor recovery. Exp Neurol. 2023;368:114479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang Y, Wang B, Fu X, Guan S, Han W, Zhang J, Gan Q, Fang W, Ying W, Qu X. Exogenous NAD(+) administration significantly protects against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat model. Am J Transl Res. 2016;8:3342-3350. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Shukla S, Sharma A, Pandey VK, Raisuddin S, Kakkar P. Concurrent acetylation of FoxO1/3a and p53 due to sirtuins inhibition elicit Bim/PUMA mediated mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in berberine-treated HepG2 cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016;291:70-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matasic DS, Brenner C, London B. Emerging potential benefits of modulating NAD(+) metabolism in cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018;314:H839-H852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yaku K, Nakagawa T. NAD(+) Precursors in Human Health and Disease: Current Status and Future Prospects. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2023;39:1133-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhao K, Tang J, Xie H, Liu L, Qin Q, Sun B, Qin ZH, Sheng R, Zhu J. Nicotinamide riboside attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury via regulating SIRT3/SOD2 signaling pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;175:116689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Huang Y, Xu W, Zhou R. NLRP3 inflammasome activation and cell death. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:2114-2127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 1074] [Article Influence: 214.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Luo T, Jia X, Feng WD, Wang JY, Xie F, Kong LD, Wang XJ, Lian R, Liu X, Chu YJ, Wang Y, Xu AL. Bergapten inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and pyroptosis via promoting mitophagy. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2023;44:1867-1878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lin Q, Li S, Jiang N, Shao X, Zhang M, Jin H, Zhang Z, Shen J, Zhou Y, Zhou W, Gu L, Lu R, Ni Z. PINK1-parkin pathway of mitophagy protects against contrast-induced acute kidney injury via decreasing mitochondrial ROS and NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Redox Biol. 2019;26:101254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 73.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Qiu Z, He Y, Ming H, Lei S, Leng Y, Xia ZY. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Aggravates High Glucose- and Hypoxia/Reoxygenation-Induced Injury through Activating ROS-Dependent NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated Pyroptosis in H9C2 Cardiomyocytes. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:8151836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 37.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mo G, Liu X, Zhong Y, Mo J, Li Z, Li D, Zhang L, Liu Y. IP3R1 regulates Ca(2+) transport and pyroptosis through the NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Cell Death Discov. 2021;7:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Muñoz-Planillo R, Kuffa P, Martínez-Colón G, Smith BL, Rajendiran TM, Núñez G. K⁺ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity. 2013;38:1142-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1562] [Cited by in RCA: 1729] [Article Influence: 133.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wang F, Liang Q, Ma Y, Sun M, Li T, Lin L, Sun Z, Duan J. Silica nanoparticles induce pyroptosis and cardiac hypertrophy via ROS/NLRP3/Caspase-1 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2022;182:171-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wang H, Liang X, Luo G, Ding M, Liang Q. Protection effect of nicotinamide on cardiomyoblast hypoxia/re-oxygenation injury: study of cellular mitochondrial metabolism. Mol Biosyst. 2016;12:2257-2264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin Q, Zuo W, Liu Y, Wu K, Liu Q. NAD(+) and cardiovascular diseases. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;515:104-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu L, Wang P, Liu X, He D, Liang C, Yu Y. Exogenous NAD(+) supplementation protects H9c2 cardiac myoblasts against hypoxia/reoxygenation injury via Sirt1-p53 pathway. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2014;28:180-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ying W. NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:179-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1024] [Cited by in RCA: 1158] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bruzzone S, Guida L, Zocchi E, Franco L, De Flora A. Connexin 43 hemi channels mediate Ca2+-regulated transmembrane NAD+ fluxes in intact cells. FASEB J. 2001;15:10-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Pillai VB, Sundaresan NR, Kim G, Gupta M, Rajamohan SB, Pillai JB, Samant S, Ravindra PV, Isbatan A, Gupta MP. Exogenous NAD blocks cardiac hypertrophic response via activation of the SIRT3-LKB1-AMP-activated kinase pathway. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:3133-3144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Song D, Liu X, Liu R, Yang L, Zuo J, Liu W. Connexin 43 hemichannel regulates H9c2 cell proliferation by modulating intracellular ATP and [Ca2+]. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2010;42:472-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Shi J, Zhao Y, Wang K, Shi X, Wang Y, Huang H, Zhuang Y, Cai T, Wang F, Shao F. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526:660-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2573] [Cited by in RCA: 5025] [Article Influence: 456.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Li A, Yu Y, Ding X, Qin Y, Jiang Y, Wang X, Liu G, Chen X, Yue E, Sun X, Zahra SM, Yan Y, Ren L, Wang S, Chai L, Bai Y, Yang B. MiR-135b protects cardiomyocytes from infarction through restraining the NLRP3/caspase-1/IL-1β pathway. Int J Cardiol. 2020;307:137-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pomerantz BJ, Reznikov LL, Harken AH, Dinarello CA. Inhibition of caspase 1 reduces human myocardial ischemic dysfunction via inhibition of IL-18 and IL-1beta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:2871-2876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/