Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.113783

Revised: September 17, 2025

Accepted: November 18, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 134 Days and 15.4 Hours

Patient consent discussion is an essential part of preoperative patient preparation. It is the main basis of decision making for the patient. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been established as the standard treatment option for symptomatic aortic stenosis-patients. Current guidelines recommend transfemoral TAVI for patients aged 70 years or older, independently of the surgical risk and for patients below 70 years of age if they are at high surgical risk.

To evaluate beneficial aspects of an explanatory video in addition to conventional medical counseling.

The study was conducted as a prospective, single-arm, monocentric cohort study. Eligible patients received conventional medical counseling, followed by an educational video. Evaluation of the conventional counseling and the educational video was obtained through a 32-item questionnaire. Two hypotheses were tested: Hypothesis 1: Showing an explanatory video in addition to the standard patient consent discussion improves the mediation of medical facts; and hypothesis 2: Showing an explanatory video in addition to the standard patient consent dis

In total, 66 patients, scheduled for transfemoral TAVI were included, 59% of them were male and 41% female, averaging 81 ± 6.1 years old. Conventional medical counseling by the attending physician was the major criterium for overall patient satisfaction and had more influence on the absence of preprocedural tension than the transfer of additional factual knowledge through the video. Nearly two-thirds (61%) reported that the video enhanced their understanding of the procedure’s benefits, while 42% indicated a better understanding of the potential risks and 56% felt that watching the video contributed to decreased preprocedural tension.

Conventional medical counseling was most important for overall patient satisfaction. Educational videos aid in information transfer, in the reduction of preprocedural tension and were strongly sought after by the patients.

Core Tip: We performed a prospective, single-arm, monocentric cohort-study to evaluate possible beneficial aspects of an explanatory video in addition to conventional patient consent discussion in an elderly patient population which was scheduled to receive transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve implantation. In our study, we could show that conventional medical counseling was the major criterium for patient satisfaction and had more influence on preprocedural composure than the transfer of additional factual knowledge by the video. However, educational videos may aid in information transfer and composure-induction and were strongly sought after by the patients.

- Citation: Genske F, Riepe A, Rawish E, Stiermaier T, Eitel I, Frerker C, Schmidt T. Importance of digital media in patient education for transcatheter aortic valve implantation. World J Cardiol 2026; 18(1): 113783

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v18/i1/113783.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v18.i1.113783

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) has been introduced in 2002 by Alain Cribier[1]. Since then, TAVI has been established as the standard treatment option for symptomatic patients with aortic stenosis. Current guidelines recommend transfemoral TAVI for patients aged 70 years or older, independently of the surgical risk and for patients below 70 years of age if they are at high surgical risk[2]. In Germany (and many other countries) the consent discussion between a doctor and the patient is required by law and regulated by the German civil law code (§ 630e Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch). The consent discussion is the main basis of decision-making for the patient and is divided into diagnosis, therapy, process of the procedure and risks and benefits. Additionally therapeutic (or diagnostic) alternatives need to be mentioned. This enables the patient to take the decision autonomously after weighing the potential risks against the benefits. The patient needs to be given a sufficient amount of time to weigh the pros and cons. To further support the patient in his decision and to provide proof of the consent, nowadays standardized forms of consent are used.

Digital health is a collective term that describes the use of digital information, data and communication technologies which aid in the collection, distribution and analysis of health-related information. Its general aim is to improve the health of individuals and of the overall population, as well as patient education and access to health services[3]. Recently, video-assisted learning interventions have shown to be useful and effective implementing healthy lifestyles and increasing awareness for its importance, especially for people with chronic diseases[4].

Due to the advancements in technology in recent years, the way patients and health providers interact has changed. Globally about 6.75 million web searches regarding medical advice are carried out each day[5]. A study by Ahmad et al[6] was able to show that the use of internet-based sources improves patients’ abilities to handle their conditions and enables them to interact more confidently with their attending physician.

Until today, the use of digital media, especially videos, is not standard care in patient education and it is not routinely utilized to aid patient consent before TAVI. As the incidence of almost any disease rises with higher age, patient consent discussions are usually targeted towards an elderly population for which the use and acceptance of digital media may be unusual. Until this day the use of digital media to aid patient consent discussion for the elderly has not been studied. We performed a systematic study to evaluate the beneficial aspects of an explanatory video in addition to conventional patient consent discussion in an elderly patient population who was scheduled to receive transfemoral TAVI.

The present study is a prospective, single-arm, monocentric cohort study conducted at the Heart Center of the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck. Its aim was to evaluate possible beneficial aspects of an explanatory video in addition to conventional patient consent discussions for patients scheduled for transfemoral TAVI. Two hypotheses were tested: Hypothesis 1: Showing an explanatory video in addition to the standard patient consent discussion improves the mediation of medical facts; and hypothesis 2: Showing an explanatory video in addition to the standard patient consent discussion improves patient satisfaction and confidence.

Participation was offered to all patients scheduled for transfemoral TAVI at the University Heart Center Lübeck, Germany after a conventional medical explanatory discussion, who had consented in writing to the procedure and did not have any visual or auditory impairments that could affect their assessment of the video. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows: Inclusion criteria: Age > 18 years, patients of any gender, scheduled for transfemoral TAVI; exclusion criteria: Visual impairment preventing video viewing, auditory impairment preventing understanding of video audio, receiving transaxillary or transapical TAVI, patients deemed incapable of providing consent by the treating physician and insufficient knowledge of the German language.

Each patient initially received conventional medical counseling about the transfemoral TAVI procedure by their attending physician. This counseling involved a standardized patient consent form that used text and diagrams to explain the TAVI procedure as well as possible complications. The form was given to the patients before the oral explanation by their attending physician to prepare them for the counseling. The physician then detailed the procedure’s process, benefits, and risks, followed by addressing any patient-specific questions. The attending physician who performed the counseling was not informed about the patients’ participation in this study.

After routine medical counselling, the patient was asked to participate in the study. Post-consent for study parti

Following the video, the patients completed a 32-item questionnaire assessing clinical characterization of the study population and their media behavior, an evaluation of the conventional information procedure, and an evaluation of the TAVI educational video. Data were scaled nominally, ordinally, or on a five or seven-point Likert scale with verbal scaling. Demographic data and media usage patterns were collected. If a participant owned a smartphone, tablet, or computer, their confidence in using them was assessed on a five-point Likert scale (Table 1). Participants rated the conventional counseling session in terms of understanding the potential benefits and risks of the procedure, satisfaction with the session, personalized attention received, and the reduction of preprocedural tension. These aspects were rated on a seven-point Likert scale (Table 1). Finally, participants evaluated the educational video on TAVI in terms of enhancing understanding of potential benefits and risks, addressing unasked questions, clarity, and the desire for video use in future consultations using the same seven-point Likert scale shown in Table 1.

| Scale | |

| Five-point Likert scale | Predominantly unsure; neither unsure nor confident; predominantly confident; confident; very confident |

| Seven-point Likert scale | Strongly disagree; disagree; slightly disagree; neutral; slightly agree; agree; strongly agree |

A key aim of the counseling process is to reduce the patients’ tension before the upcoming procedure. We performed a linear regression analysis to assess potential influencing factors on patient tension following the overall counseling process. This analysis considered the reduction of preprocedural tension as the dependent variable and examined the impact of three independent variables: (1) Absence of preprocedural tension after the complete counseling process (conventional counseling and additional educational video); (2) Understanding the benefits following conventional medical counseling; and (3) Understanding the benefits following viewing the additional educational video.

In a subsequent linear regression model with different independent variables, the absence of preprocedural tension following the complete counseling process (medical counseling and TAVI video), was analyzed as the dependent variable. The independent variables were the severity of comorbidities based on the logistic European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation score (EuroSCORE), as well as on the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS)-score, and absence of tension following only conventional medical counseling.

In a further regression analysis, factors influencing patients’ desire to view an educational video were examined. The desire to see such a video was set as the dependent variable, and the independent variables included the understanding of the procedure’s benefits and risks following conventional medical counseling, and the understanding of these aspects after viewing the TAVI educational video.

Approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Campus Lübeck (approval No. 21-304), the study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the hospital and the guidelines laid out in the Declaration of Helsinki. Accordingly, only participants capable of providing informed consent were included. All participants were orally and in writing informed about the study procedure, objectives, and data protection regulations. A specifically designed information sheet with a consent form was used for written consent. Participant anonymity was maintained through the assignment of identification numbers.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (SPSS 25.0 for Windows, Armonk, NY, 2017). Frequency distributions of nominal and ordinal data were analyzed using the exact χ2 test, chosen for its reduced sensitivity to small sample sizes in contingency tables. Deviations from this test were specifically noted. The effect size of differences in frequency distributions was calculated using Cramer’s V, with a value of 0.1 indicating a small effect size, 0.3 a medium effect size, and 0.5 a large effect size. The influence of independent variables on a dependent variable was examined through linear regression analysis.

In total, 66 patients were included, 59% of them were male and 41% female, averaging 81 ± 6.1 years old. A majority displayed one or more comorbidities, predominantly arterial hypertension and coronary artery disease. Detailed comor

| Disease | Frequency of occurrence |

| CAD | 63% (42/66) |

| One vessel CAD | 27% (18/66) |

| Two vessel CAD | 18% (12/66) |

| Three vessel CAD | 18% (12/66) |

| Peripheral arterial occlusive disease | 17% (11/66) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 29% (19/66) |

| Arterial hypertension | 88% (58/66) |

| Chronic kidney insufficiency | 5% (35/66) |

| Status post apoplex | 17% (11/66) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 27% (18/66) |

All patients were either currently or previously employed, with 36% regularly using computers at work. Regarding personal digital equipment, 49% owned a smartphone, 44% owned a computer, and 27% owned a tablet. Double entries were possible. The majority felt confident in using these devices (Table 3). Half of the patients (47%) spent time on the internet daily, while 97% watched television, with 69% spending over 120 minutes daily. More than half (56%) preferred newspapers for information, with only 15% considering digital media as reliable without constraints.

| Electronic device | N (ownership) | Predominantly unsecure | Neither unsecure nor confident | Predominantly confident | Confident | Very confident | |

| Computer | 29 | 20% (6/29) | 7% (2/29) | 17% (5/29) | 31% (9/29) | 24% (7/29) | |

| Tablet | 18 | 0% (0/18) | 16 % (3/18) | 16% (3/18) | 44% (8/18) | 22% (4/18) | |

| Smartphone | 32 | 13% (4/32) | 28% (9/32) | 19% (6/32) | 19% (6/32) | 22% (7/32) | |

The evaluation of conventional counseling was conducted using a seven-point Likert scale (Table 1). It focused on patients’ acquired understanding of potential benefits and risks associated with the TAVI procedure, the perception of individualized attention during the counseling, their tension in anticipation of the intervention following the consul

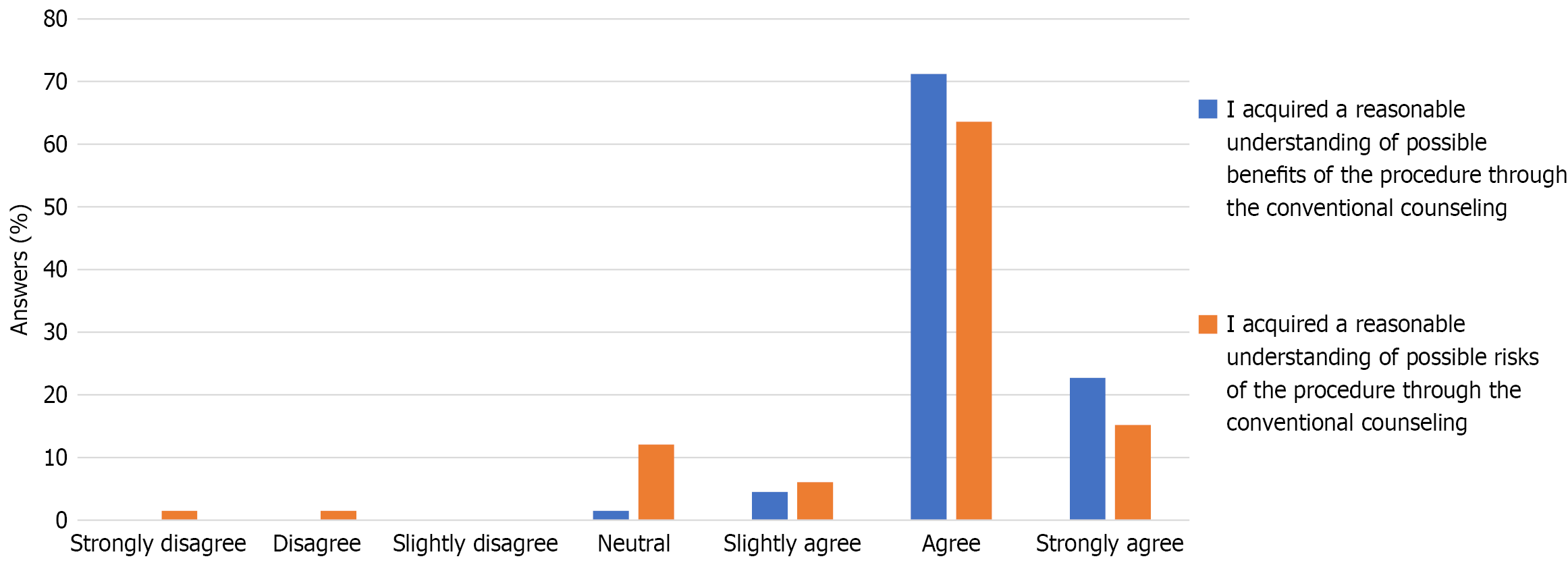

A majority of the patients agreed or strongly agreed that they had developed a good understanding of both the potential benefits (94%; 62/66) and risks (79%; 52/66) of the procedure (Figure 1). While the understanding of benefits and risks of the procedure varied with a trend towards better understanding of the benefits than the risks, there was a medium to high correlation between them [χ2 = 44.709; degrees of freedom (df) = 15; P = 0.034, Cramer-V = 0.475]. After the counseling process all participants stated to have gained an understanding of the benefits (Figure 1).

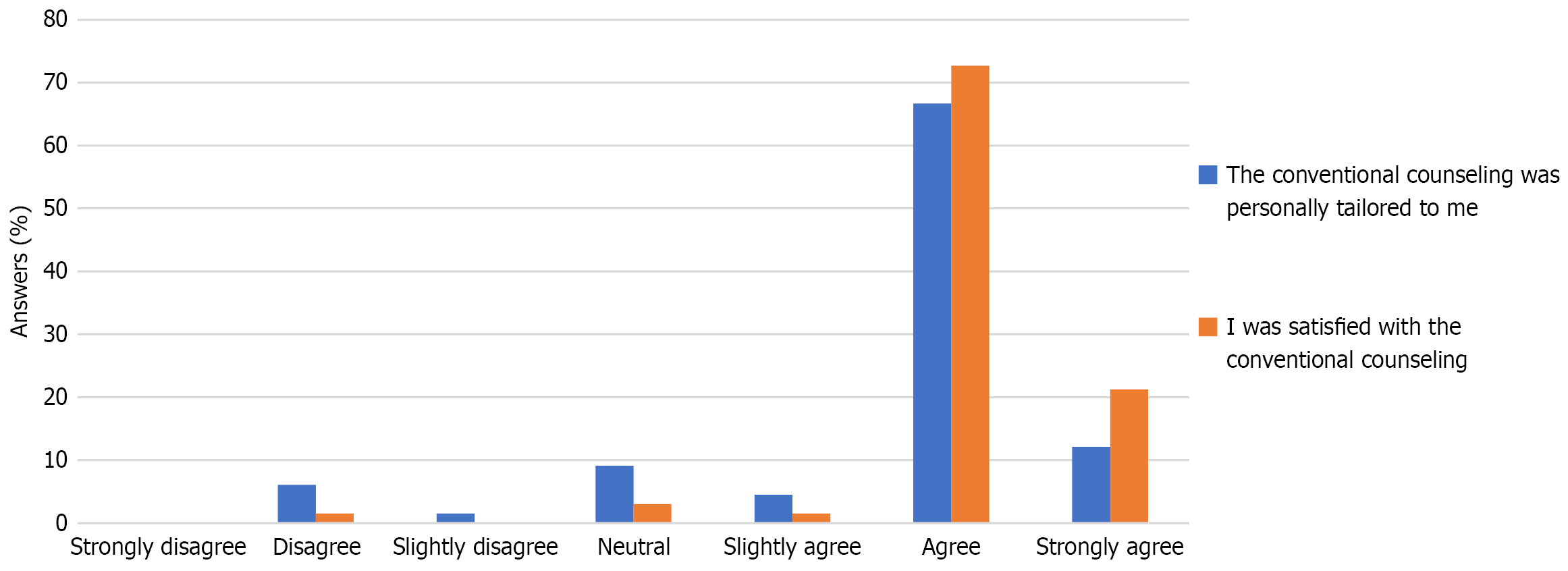

Over 90% of participants agreed or strongly agreed on their satisfaction with the conventional medical counseling (Figure 2). The perception of the counseling being tailored to individual needs was lower, with still about three-quarters (79%) agreeing or strongly agreeing. Indeed, there was a strong correlation between the satisfaction with medical counseling and the perception of it being personalized (χ2 = 110.663; df = 20; P < 0.001, Cramer-V = 0.647).

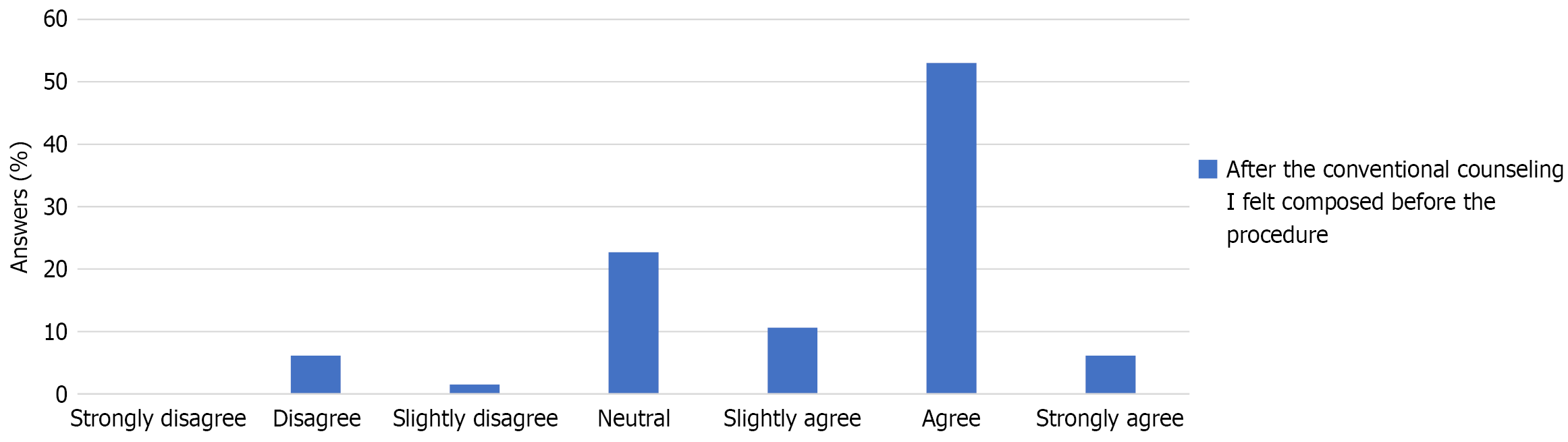

About 59% of the participants felt composed about the planned procedure after counseling, while less than 10% felt tense (Figure 3). A linear regression analysis revealed that the overall satisfaction with conventional medical counseling was the only significant predictor of the absence of a patient’s tension before the procedure, irrespective of their understanding of the potential benefits or risks (R = 0.397, R2 corrected = 0.144, regression coefficient = 0.679, standard error = 0.199, Beta = 0.397, T = 3.14, P = 0.001; Table 4).

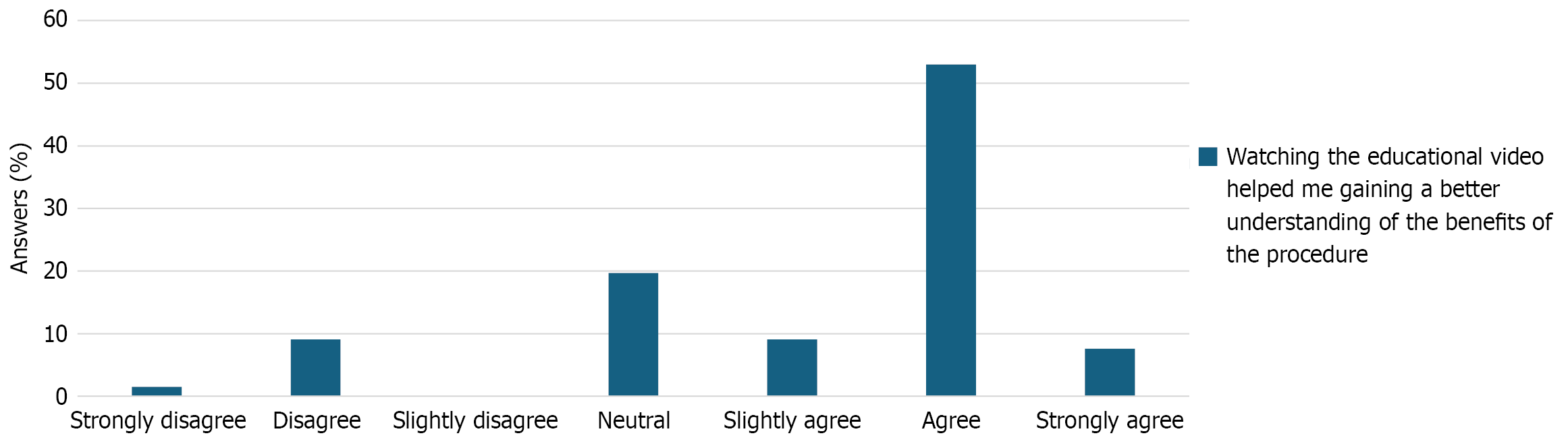

The educational video addressed the procedure’s execution, potential benefits, and risks. Around 90% of participants (59/66) agreed or strongly agreed that the video was clear and easily understandable. Nearly two-thirds (61%) reported that the video enhanced their understanding of the procedure’s benefits compared to conventional medical counseling alone, while 42% indicated a better understanding of the potential risks. More than half of the participants (56%) felt that watching the video contributed to decreased tension before the procedure (Figure 4).

The present study also inquired whether participants received answers to questions about the procedure’s potential benefits or risks from the TAVI educational video - questions they might have been reluctant to ask during the medical consultation. A small portion of participants agreed or partially agreed that they gained additional information about the procedure’s benefits (18%) or risks (20%) from the video, which they had hesitated to ask during the consultation. There is a significant correlation between these two variables (χ2 = 109.940; df = 20; P < 0.001; Cramer-V = 0.645). Despite the small number of participants reporting additional information gain on the potential benefits or risks of the procedure, 70% expressed a desire for educational videos in future interventions.

The linear regression analysis to assess potential influencing factors on patient tension revealed that conventional medical counseling had a higher influence on the presence of preprocedural tension than the understanding of benefits conveyed through either medical counseling or the TAVI educational video (Table 5).

| R | R2 adjusted | Regression coefficient B | SE | Beta | T value | P value | |

| Composure after conventional counseling | 0.600 | 0.350 | 0.661 | 0.126 | 0.519 | 5.256 | 0.000 |

| Understanding of benefits after conventional counseling | 0.637 | 0.387 | 0.584 | 0.281 | 0.205 | 2.076 | 0.042 |

| Understanding of benefits after watching the video | 0.665 | 0.416 | 0.214 | 0.106 | 0.194 | 2.015 | 0.048 |

The subsequent regression analysis on patient tension after the complete counseling process (medical consultation and TAVI educational video) found that the conventional counseling significantly influences how patients perceive the video augmentation. The less tense a patient is after conventional counseling, the more the video augmentation contributes to their composure (Table 4). The severity of comorbidities, as measured by logistic EuroSCORE or STS-score, did not impact preprocedural tension. In the third regression analysis, the most significant factor associated with patients’ desire to view an educational video before a procedure was the reduction of preprocedural tension achieved through conventional counseling (Table 6).

| R | R2 adjusted | Regression coefficient B | SE | Beta | T value | P value | |

| Composure after watching the educational video | 0.568 | 0.312 | 0.319 | 0.067 | 0.492 | 4.754 | 0.000 |

| Understanding of benefits of the procedure after watching the educational video | 0.619 | 0.364 | 0.185 | 0.074 | 0.258 | 2.495 | 0.015 |

The major findings of this study are: (1) Conventional medical counseling by the attending physician is the major criterium for overall patient satisfaction, especially when personally tailored to the patient; (2) Conventional medical counseling by the attending physician has more influence on the reduction of preprocedural tension than the transfer of factual knowledge of risks and benefits through an additional educational video; (3) Educational videos may aid in information transfer and tension reduction but cannot replace conventional medical counseling; and (4) Patient acceptance of the additional educational videos was high, and most of the participants would wish their support also for future interventions.

Previous studies could show that complex matters are more easily remembered if they are presented as a combination of words and pictures, rather than as words alone[7]. Standard procedure for patient consent discussions consists of the spoken medical counseling and handing the patient a consent form which comprises a written explanation, supported by a schematic representation of the procedure. In our study almost all participants (> 90%) were satisfied with the oral counseling and reported a good understanding of the risks (79%) and benefits (94%) of the intervention. After the conventional medical counseling, almost two thirds of the participants (59%) reported to feel calm and serene about the procedure. It could be shown that participants were more satisfied with the counseling if they had the impression that it was personally tailored to them. Patient satisfaction with medical counseling is mainly influenced by empathy and compassion of the counseling physician[8]. Furthermore, we could show that only the overall patient satisfaction matters, whereas the understanding of possible risks and benefits of the procedure did not make a significant difference (Table 4).

These findings are supported by recent literature. In a study by Wang et al[9], the influence of communication on their physician-patient-relation was evaluated. They could show that the ability of the physician to alter his perspective as well as his empathy contributed most to the communication and thus to the physician-patient-relation. High quality communication between a physician and his patient has major influence on patient satisfaction. This is the case even if the communication between the physician and the patient does not take place in persona but rather via video consultation, as Tenfelde et al[8] could show. In their study, they investigated which patient-, physician- and technology-related factors contributed most to patient satisfaction in the context of video consultations. Whereas age, sex and socioeconomic status had no influence on patient satisfaction, physician- and technology-related factors (internet connection issues, privacy concerns, digital literacy, etc.) did. Our study did not investigate the latter, although digital literacy of our study population was evaluated (Table 3). The data was not evaluated regarding possible effects of the study populations’ digital literacy on the understanding of the educational video and thereby on preprocedural tension.

Videos to support medical counseling are currently not routinely used. A literature review conducted in 2021 analyzed the impact of digital patient education in the field of cardiology[10]. One of the main results of this review was that the use of video material significantly influenced patient consent. Compared to conventional medical counseling, the additional educational video for patients schedules for transfemoral TAVI improved knowledge transfer, reduction of fear and nervousness prior to intervention, and understanding of the procedure. In our study, more than 90% of the participants agreed that the video shown to them was easily understandable. It is worth noting that our video was created by a layperson who simply merged sequences of two separate preexisting videos without the help of professional video editing software. Only at the beginning of each segment, a short introductory sequence was added. Whilst choosing the video sequences, emphasis was put on creating short sequences that contain substantial information rather than explaining the whole procedure. It seems that the general benefits of visual support led to the overall good rating of our video by the participants even though it was not professionally produced.

In a conventional medical consultation, there is typically an asymmetrical communication dynamic where an expert imparts knowledge to a layperson (the patient). In such settings, it’s conceivable that the patient may hesitate to ask questions despite seeking answers. This is another aspect where an educational video may aid in information transfer and thereby support conventional medical counseling. After watching the educational video in addition to conventional medical counseling, 61% said they received additional information about the benefits of the procedure and 42% said they better understood the risks. These results are a key finding of our study, and suggest that the additional educational video in addition to conventional medical counseling enhanced the patients’ knowledge about the benefits and risks of the procedure and decreased tension before the procedure for more than half of the patients. This valuation is purely subjective and was not objectified, e.g. by means of a questionnaire. However, these subjective results correspond to previous studies that have been conducted on this matter. In 2008 in a study by Salzwedel et al[11], 209 patients were randomized into three groups. The first group received only conventional medical counseling, the second group additionally saw an informational video beforehand and the third group saw the same video after conventional counseling. There was no difference regarding tension and patient satisfaction, however those patients who viewed the video were better informed about the procedure in question. Another study that was performed in 2015 on patients which were scheduled for coronary angiography could show that providing an explanatory video in addition to conventional medical counseling increases the comprehension of the planned intervention, as well as the overall patient satisfaction[12].

We also assessed preprocedural tension in our study population. More than half of the participants (56%) said that watching the educational video in addition to conventional medical counseling decreased their preoperative tension. This emphasizes the incremental value of the educational video in addition to conventional medical counseling. Again, this valuation was subjective, as we did not use any score, such as the Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale to objectify tension. The importance of tension reduction before interventional procedures and operations has been proven in several studies. A prospective multi-center study by Williams et al[13] showed that preoperative nervousness and anxiety are associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality after cardio-thoracic surgery, independent of the associated operative risk score (STS-score). Kassahun et al[14] reported the same results for a study cohort of patients undergoing complex general surgery. Therefore, decreasing pre-interventional tension and stress for patients is not only a humane thing to do, but also has a direct clinical impact as it has the potential to lower morbidity and mortality rates.

The results of our study showed that tension prior to the planned intervention mainly depends on conventional counseling. Conventional counseling had a greater impact on the reduction of preprocedural tension than the transfer of factual knowledge or the additional educational video (Table 5). A further reduction in preprocedural tension by the educational video could be shown, however, it was seen mainly for participants who reported to be already composed after conventional counseling (Table 4). This leads us to conclude that the emotional support a physician can give to his patients by which he reduces their preprocedural tension cannot be substituted solely by a video. The additional knowledge conveyed through the video can support tension reduction and therefore is an important addition to conventional counseling, but on its own is not sufficient enough and can therefore not replace conventional counseling.

As there are currently no studies with a similar approach, it cannot be ruled out that a different structure of the educational video would have led to different results. This study was not balanced regarding gender. The reason for this is the gender-imbalance of the occurrence of aortic stenosis – it occurs predominantly in the male population[15]. However, gender-specific factors could have influenced the impact of the educational video and thus the results of this study. As this study was an explorative study, it could not be powered to investigate the influence of gender. Furthermore, this study was a monocentric study which did not account for cultural aspects. These should be addressed in future studies.

The present data underline the importance of thorough medical counseling and allow an insight into the value of educational videos as an addition to conventional medical counseling, especially their effect on patient satisfaction and the absence of preprocedural tension. Showing an explanatory video in addition to conventional patient counseling improves the mediation of medical facts as well as improving patient satisfaction and confidence in the planned procedure.

| 1. | Cribier A. Invention and uptake of TAVI over the first 20 years. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19:427-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Praz F, Borger MA, Lanz J, Marin-Cuartas M, Abreu A, Adamo M, Ajmone Marsan N, Barili F, Bonaros N, Cosyns B, De Paulis R, Gamra H, Jahangiri M, Jeppsson A, Klautz RJM, Mores B, Pérez-David E, Pöss J, Prendergast BD, Rocca B, Rossello X, Suzuki M, Thiele H, Tribouilloy CM, Wojakowski W; ESC/EACTS Scientific Document Group. 2025 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2025;ehaf194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 219.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Varma N, Cygankiewicz I, Turakhia M, Heidbuchel H, Hu Y, Chen LY, Couderc JP, Cronin EM, Estep JD, Grieten L, Lane DA, Mehra R, Page A, Passman R, Piccini J, Piotrowicz E, Piotrowicz R, Platonov PG, Ribeiro AL, Rich RE, Russo AM, Slotwiner D, Steinberg JS, Svennberg E. 2021 ISHNE/ HRS/ EHRA/ APHRS collaborative statement on mHealth in Arrhythmia Management: Digital Medical Tools for Heart Rhythm Professionals: From the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology/Heart Rhythm Society/European Heart Rhythm Association/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol. 2021;26:e12795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Denny MC, Vahidy F, Vu KY, Sharrief AZ, Savitz SI. Video-based educational intervention associated with improved stroke literacy, self-efficacy, and patient satisfaction. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kuwabara A, Su S, Krauss J. Utilizing Digital Health Technologies for Patient Education in Lifestyle Medicine. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2020;14:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ahmad F, Hudak PL, Bercovitz K, Hollenberg E, Levinson W. Are physicians ready for patients with Internet-based health information? J Med Internet Res. 2006;8:e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pearson HC, Wilbiks JMP. Effects of Audiovisual Memory Cues on Working Memory Recall. Vision (Basel). 2021;5:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tenfelde K, Bol N, Schoonman GG, Bunt JEH, Antheunis ML. Exploring the impact of patient, physician and technology factors on patient video consultation satisfaction. Digit Health. 2023;9:20552076231203887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Wang P. The Effects of Physicians' Communication and Empathy Ability on Physician-Patient Relationship from Physicians' and Patients' Perspectives. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2022;29:849-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oudkerk Pool MD, Hooglugt JQ, Schijven MP, Mulder BJM, Bouma BJ, de Winter RJ, Pinto Y, Winter MM. Review of Digitalized Patient Education in Cardiology: A Future Ahead? Cardiology. 2021;146:263-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Salzwedel C, Petersen C, Blanc I, Koch U, Goetz AE, Schuster M. The effect of detailed, video-assisted anesthesia risk education on patient anxiety and the duration of the preanesthetic interview: a randomized controlled trial. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:202-209, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lattuca B, Barber-Chamoux N, Alos B, Sfaxi A, Mulliez A, Miton N, Levasseur T, Servoz C, Derimay F, Hachet O, Motreff P, Metz D, Lairez O, Mewton N, Belle L, Akodad M, Mathivet T, Ecarnot F, Pollet J, Danchin N, Steg PG, Juillière Y, Bouleti C; INFOCORO investigators. Impact of video on the understanding and satisfaction of patients receiving informed consent before elective inpatient coronary angiography: A randomized trial. Am Heart J. 2018;200:67-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Williams JB, Alexander KP, Morin JF, Langlois Y, Noiseux N, Perrault LP, Smolderen K, Arnold SV, Eisenberg MJ, Pilote L, Monette J, Bergman H, Smith PK, Afilalo J. Preoperative anxiety as a predictor of mortality and major morbidity in patients aged >70 years undergoing cardiac surgery. Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kassahun WT, Mehdorn M, Wagner TC, Babel J, Danker H, Gockel I. The effect of preoperative patient-reported anxiety on morbidity and mortality outcomes in patients undergoing major general surgery. Sci Rep. 2022;12:6312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Summerhill VI, Moschetta D, Orekhov AN, Poggio P, Myasoedova VA. Sex-Specific Features of Calcific Aortic Valve Disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/