Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112978

Revised: September 10, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 135 Days and 2.7 Hours

Aortic adverse remodeling remains a critical complication following thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) for Stanford type B aortic dissection (TBAD), significantly impacting long-term survival. Accurate risk prediction is essential for optimized clinical management.

To develop and validate a logistic regression-based risk prediction model for aortic adverse remodeling following TEVAR in patients with TBAD.

This retrospective observational cohort study analyzed 140 TBAD patients under

Multivariable analysis identified several strong independent predictors of neg

This validated risk prediction model identifies aortic adverse remodeling with high accuracy using routinely available clinical parameters. False lumen involvement thoracoabdominal aorta is the strongest predictor (11.751-fold increased risk). The tool enables preoperative risk stratification to guide tailored TEVAR strategies and improve long-term outcomes.

Core Tip: This study developed and validated a logistic regression-based risk prediction model for aortic adverse remodeling following thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) in patients with type B aortic dissection. The model, incorporating routinely available clinical and imaging variables, demonstrated high predictive accuracy (area under the curve = 0.968). Pan-aortic false lumen involvement was identified as the strongest predictor, increasing the risk of adverse remodeling by nearly 12-fold. This tool facilitates preoperative risk stratification to guide personalized treatment strategies and improve long-term outcomes after TEVAR.

- Citation: Wang LF, Zhu HJ, Wang C, Yan F, Qu CZ. Logistic regression-based risk prediction of aortic adverse remodeling following thoracic endovascular aortic repair in patients with aortic dissection. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 112978

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/112978.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.112978

Aortic dissection (AD) is a critical cardiovascular emergency characterized by a tear in the aortic intima, which allows blood to enter the vessel wall and create a false lumen. According to the Stanford classification, dissections with the primary entry tear located distal to the left subclavian artery are classified as Stanford type B AD (TBAD). Epidemiological data indicate that TBAD accounts for approximately one-third of all AD cases, representing a clinically substantial entity[1]. The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying TBAD are highly complex, and its association with persistently high mortality rates sustains its status as a major focus of medical research.

Clinical trials have demonstrated that thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) offers significant advantages over traditional open surgery for TBAD, including reduced early mortality, lower perioperative complication rates, and shorter hospital stays[2,3]. This innovative approach has improved outcomes and provided a renewed hope for survival among TBAD patients. However, it is important to note that while TEVAR effectively seals the primary entry tear, distal re-entry tears often remain untreated. Consequently, persistent flow into the false lumen through these patent distal tears can lead to the formation of post-operative dissecting aortic aneurysms in a subset of patients, representing a serious long-term complication. This phenomenon, termed aortic adverse remodeling, has a direct and profound impact on long-term survival.

Further studies report that within 5 years after TEVAR, approximately 6.6% to 84% of patients develop thoracic dissecting aortic aneurysms, while 10% to 54% develop abdominal dissecting aortic aneurysms[4]. These data highlight aortic adverse remodeling as a substantial clinical concern, significantly threatening both the long-term prognosis and quality of life of TBAD patients. Therefore, early identification of risk factors for aortic adverse remodeling following TEVAR and the implementation of timely interventions are critically important. This underscores the necessity of close patient follow-up and vigilant monitoring to promptly detect and manage potential complications.

Nevertheless, accurately predicting the risk of aortic adverse remodeling following TEVAR remains challenging. The development of more comprehensive and precise predictive models continues to be a major focus and ongoing challenge in contemporary research. Therefore, this study aims to develop a risk prediction model for aortic adverse remodeling after TEVAR in patients with TBAD by retrospectively analyzing clinical data, imaging features, and surgical records from those treated at our institution. The model is intended to assist in clinical decision-making and improve risk stratification.

This retrospective observational cohort study enrolled patients with TBAD who underwent TEVAR at a tertiary municipal hospital in Zhangjiajie, Hunan Province, China, between January 2019 and November 2024. Based on a single-center database, patients were stratified into two groups according to their postoperative aortic remodeling outcome, defined as an annual growth rate of the aortic diameter exceeding 2.9 mm/year or not. Eligible participants were selected according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and comprehensive clinical data were collected. The study protocol adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Inclusion criteria: Age ≥ 18 years. Radiologically confirmed diagnosis of TBAD by computed tomography angiography (CTA). Underwent successful TEVAR procedure. Availability of complete clinical and imaging follow-up data for at least 6 months postoperatively.

Exclusion criteria: Diagnosis of TBAD, aortic pseudoaneurysm, penetrating aortic ulcer, or intramural hematoma. Pre-existing severe hepatic or renal dysfunction, or multi-organ failure.

Grouping method: From the overall cohort that met the above inclusion and exclusion criteria, patients were categorized into two groups based on the annual growth rate (ΔD/year) of the maximum aortic diameter (typically measured at the site showing the most significant diameter change.) after TEVAR. The annual growth rate was calculated from measurements obtained on the postoperative day 7 and the most recent follow-up CTA scans. Adverse remodeling group: Defined by an annual aortic diameter growth rate of ΔD/year > 2.9 mm/year; favorable remodeling Group: Defined by an annual aortic diameter growth rate of ΔD/year ≤ 2.9 mm/year[5].

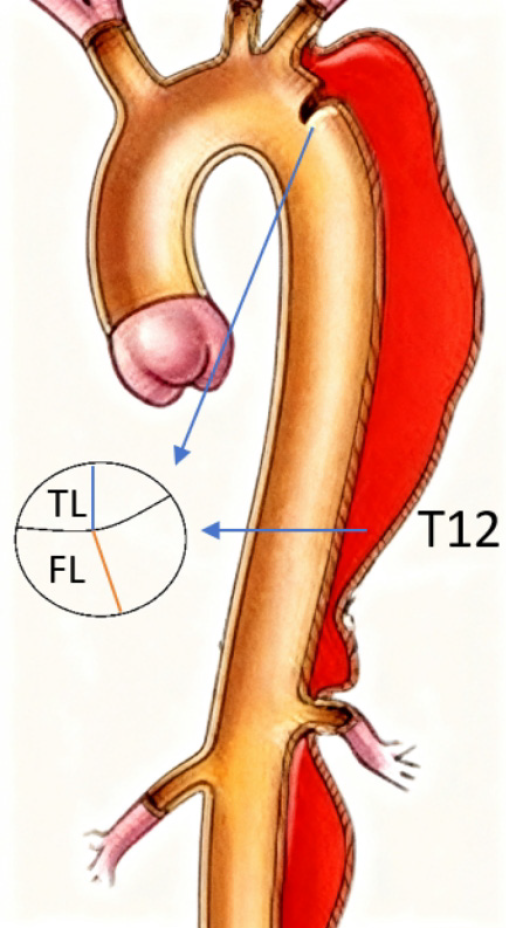

Based on a review of prognostic literature, seven core predictor variables were prespecified for this study: True lumen diameter at the primary entry tear; false lumen diameter at the primary entry tear; true lumen diameter at the T12 vertebral level; false lumen diameter at the T12 vertebral level; extent of dissection involvement; timing of surgery; patency status of the false lumen. Variable selection adhered to the principles of variance inflation factor < 3 and prioritizing clinical significance, with the final model constrained to ≤ 9 predictors.

The sample size was calculated according to the standard requiring ≥ 15-20 events per predictor variable. Accounting for up to 9 potential predictors: Minimum required sample: 9 predictors × 15 cases = 135 patients. With 15% allowance for attrition (e.g., loss to follow-up): 135 × 1.15 = 156 patients. Accounting for an anticipated loss to follow-up of 5 cases, a total of 161 patients were targeted for enrollment to ensure 156 completed the study.

Demographic and clinical parameters were systematically extracted from medical records: Sex; age; comorbidities; smoking history; alcohol consumption history; pain location; body mass index (BMI); number of entry tears in the descending thoracic aorta; number of entry tears in the abdominal aorta; operative duration; intraoperative blood loss; true and false lumen diameters at the primary entry tear; true and false lumen diameters at the T12 vertebral level; extent of false lumen involvement; number of branch vessels originating from the false lumen; timing of surgery.

The annual aortic diameter growth rate (ΔD/year) was calculated using the following formula: ΔD/year = (D-final - D-initial)/(Follow-up time in years).

D-initial was defined as the maximum aortic diameter (measured at the site of most significant change) on the first post-operative CTA scan, typically obtained on postoperative day 7; D-final was defined as the maximum aortic diameter on the most recent follow-up CTA scan. All CTA measurements were performed by two independent vascular surgeons using standardized techniques, and the average value was used for analysis. Discrepancies exceeding 10% were adjudicated by a senior radiologist. Follow-up protocol consisted of CTA scans at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively, and annually thereafter. The number of CTA scans per patient and the time intervals between scans were recorded for analysis.

Dual independent data entry with cross-verification was performed to ensure accuracy. All forms underwent consistency validation prior to database locking. Data were curated in Microsoft Excel®, then migrated to SPSS v26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) for statistical processing.

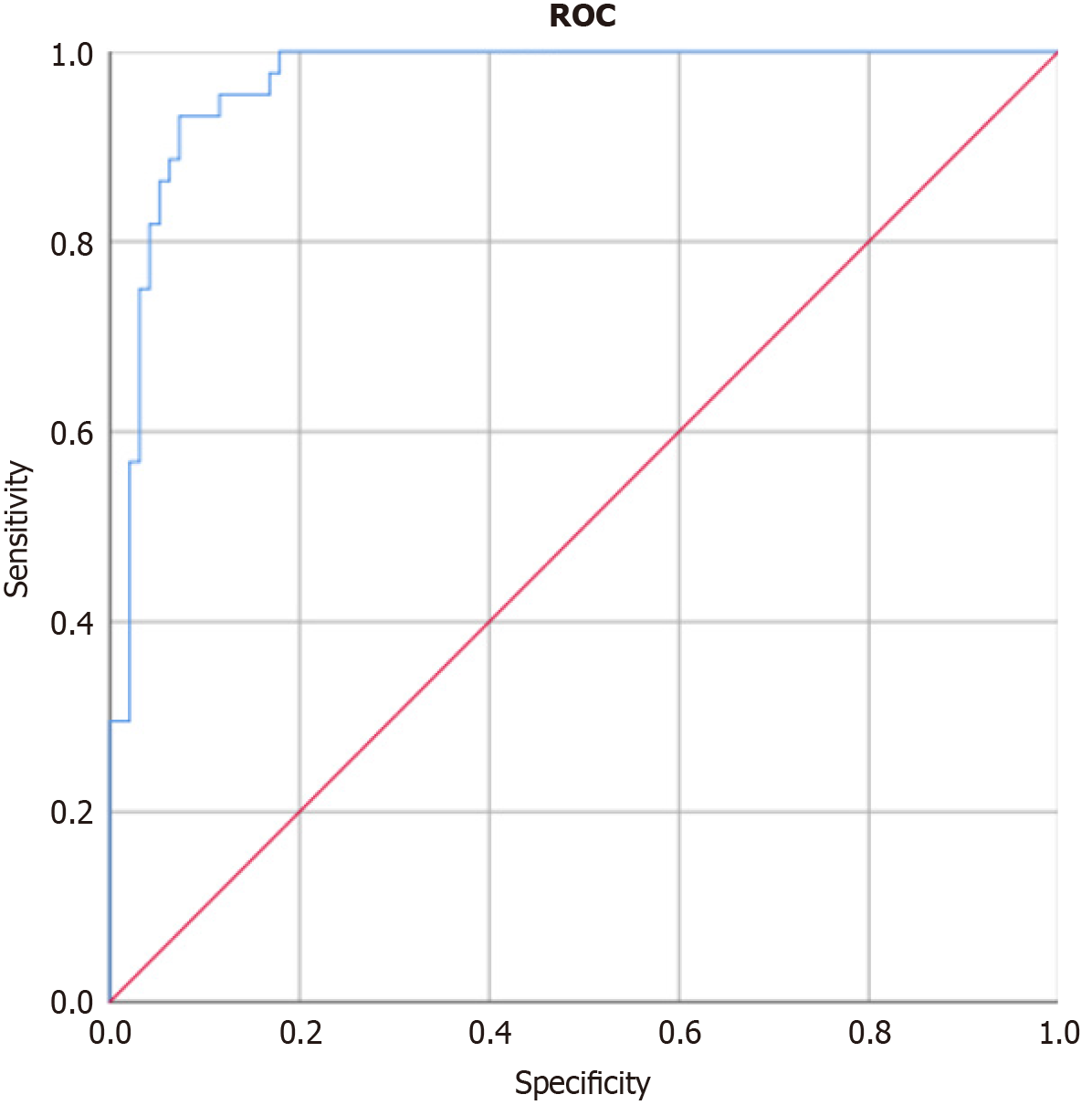

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD; non-normally distributed continuous variables as median (interquartile range); categorical variables as frequencies (percentages). Intergroup comparisons utilized χ² tests. Following variable selection and coding, univariate analysis identified factors with P < 0.05 for inclusion in multivariable logistic regression to determine independent predictors of aortic adverse remodeling post-TEVAR in TBAD patients. Model performance was assessed via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with area under the curve (AUC) calculation, while calibration was evaluated using the Hosmer-Lemeshow (HL) goodness-of-fit test; a P > 0.05 for the HL test indicated adequate model fit (no significant difference between predicted and observed outcomes), whereas P < 0.05 suggested poor fit. Statistical significance was defined as two-tailed P < 0.05 throughout the analysis.

A total of 140 TBAD patients who underwent TEVAR, met the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, and completed the required follow-up were ultimately included in the final analysis. Based on residual aortic diameter growth rates during follow-up (> 2.9 mm/year), patients were stratified into favorable remodeling (n = 95) and adverse remodeling (n = 45) groups. The favorable remodeling group comprised 49 males and 46 females (mean age: 57.37 ± 13.97 years), while the adverse remodeling group included 22 males and 23 females (mean age: 56.84 ± 14.34 years). No significant dif

| Favorable remodeling group (n = 95) | Adverse remodeling group (n = 45) | t/χ² | P value | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 49 (51.58) | 22 (48.89) | 0.088 | 0.766 |

| Female | 46 (48.42) | 23 (51.11) | ||

| Age | 57.37 ± 13.97 | 56.84 ± 14.34 | 0.205 | 0.837 |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 90 (94.74) | 39 (86.67) | 2.75 | 0.097 |

| Diabetes | 46 (48.42) | 23 (51.11) | 0.088 | 0.766 |

| Coronary heart disease | 34 (35.79) | 14 (31.11) | 0.297 | 0.586 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 37 (38.95) | 15 (33.33) | 0.412 | 0.521 |

| Chronic renal failure | 7 (7.37) | 4 (8.89) | 0.098 | 0.755 |

| Smoking history | 29 (30.53) | 10 (22.22) | 1.048 | 0.306 |

| Alcohol consumption | 19 (20) | 12 (26.67) | 0.787 | 0.375 |

| Pain location | ||||

| Chest pain/Back pain | 47 (49.47) | 24 (53.33) | 0.182 | 0.670 |

| Abdominal pain | 10 (10.53) | 6 (13.33) | 0.238 | 0.626 |

| Chest and abdominal pain | 38 (40) | 15 (33.33) | 0.577 | 0.448 |

| BMI | 23.64 ± 7.64 | 22.15 ± 9.45 | 1.042 | 0.299 |

No significant differences were observed between groups in the number of entry tears in the descending thoracic aorta, number of entry tears in the abdominal aorta, operative duration, or intraoperative blood loss (P > 0.05). Statistically significant differences were identified in the following parameters (P < 0.05). True and false lumen diameters at the primary entry tear; true and false lumen diameters at the T12 vertebral level; extent of false lumen involvement; Number of branch vessels originating from the false lumen; timing of surgery; detailed comparative data are presented in Table 2.

| Favorable remodeling group (n = 95) | Adverse remodeling group (n = 45) | t/χ² | P value | |

| True lumen diameter at primary entry tear | 14.45 ± 4.69 | 11.13 ± 3.68 | 4.137 | 0.001 |

| False lumen diameter at primary entry tear (mm) | 17.05 ± 2.05 | 20.42 ± 3.58 | -7.061 | 0.001 |

| True lumen diameter at T12 level (mm) | 12.66 ± 3.62 | 10.24 ± 3.28 | 3.804 | 0.001 |

| False lumen diameter at T12 level (mm) | 15.20 ± 1.85 | 19.58 ± 2.77 | -11.060 | 0.001 |

| Extent of false lumen involvement | ||||

| Thoracic aorta | 7 (7.37) | 0 | 7.461 | 0.024 |

| Suprarenal abdominal aorta | 41 (43.16) | 13 (28.89) | ||

| Thoracoabdominal aorta | 47 (49.47) | 32 (71.11) | ||

| Branch vessels from false lumen | 1.95 ± 0.66 | 2.49 ± 0.84 | -4.143 | 0.001 |

| Entry tears in descending aorta | 3.04 ± 0.82 | 3.13 ± 0.82 | -0.614 | 0.540 |

| Entry tears in abdominal aorta | 1.95 ± 0.66 | 1.93 ± 0.65 | 0.118 | 0.906 |

| Patency of false lumen | 34 (35.79) | 29 (64.44) | 10.131 | 0.002 |

| Timing of surgery | ||||

| Acute phase | 4 (4.21) | 9 (20) | 17.672 | 0.001 |

| Subacute phase | 88 (92.63) | 29 (64.44) | ||

| Chronic phase | 3 (3.16) | 7 (15.56) | ||

| Operative duration (minute) | 70.56 ± 15.12 | 69.73 ± 17.88 | 0.063 | 0.95 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 29.47 ± 12.93 | 32.12 ± 15.24 | -0.224 | 0.823 |

| Left subclavian artery revascularization | ||||

| Performed | 33 (34.74) | 19 (42.22) | 0.733 | 0.392 |

| Not performed | 62 (65.26) | 26 (57.78) |

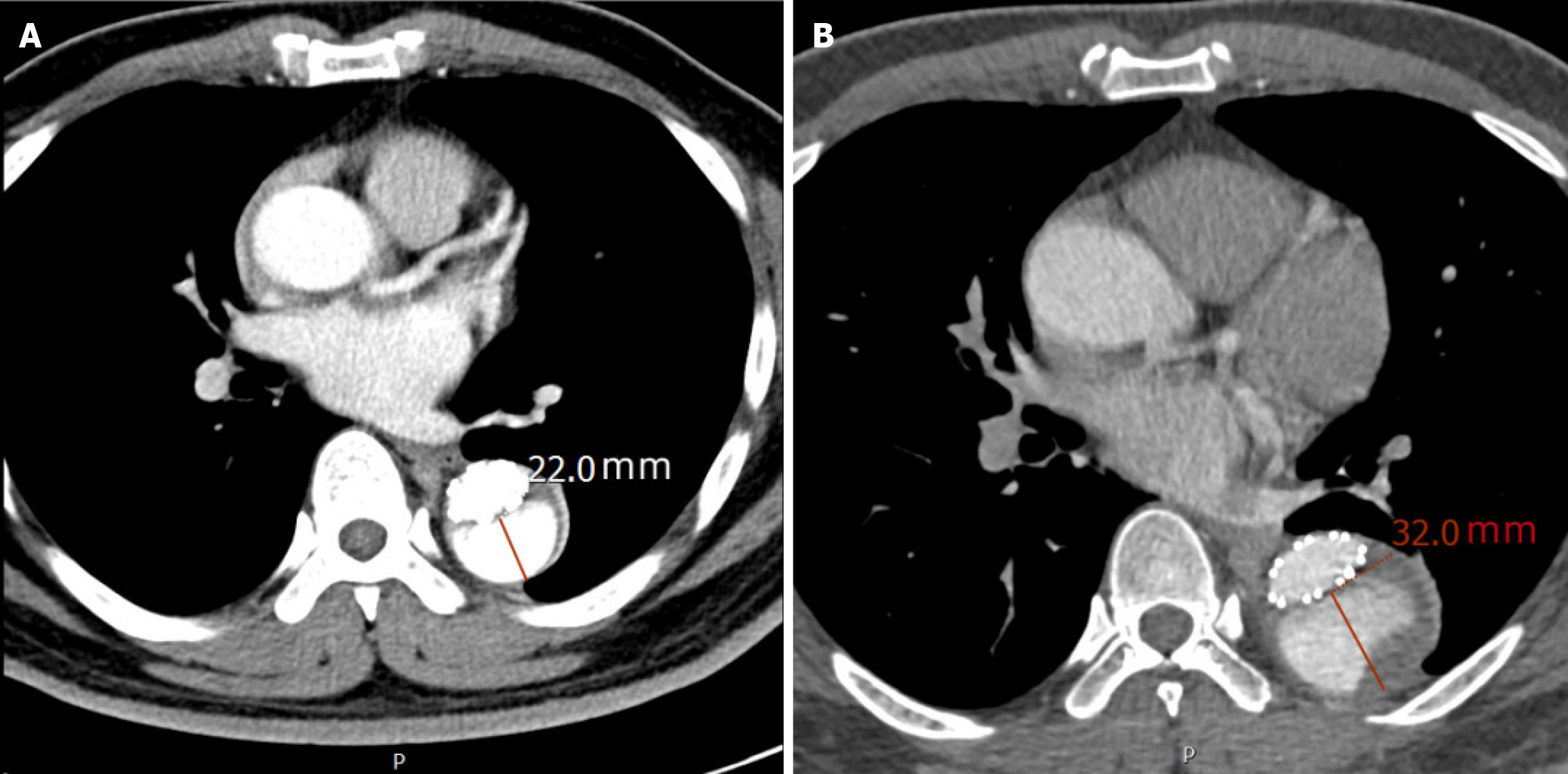

The average follow-up duration for the entire cohort was 28.5 ± 9.3 months. The adverse remodeling group had a significantly longer follow-up time (35.2 ± 8.1 months) compared to the favorable remodeling group (25.1 ± 7.6 months) (P < 0.001), which is consistent with the more aggressive monitoring protocol for patients exhibiting aortic expansion. The average number of postoperative CTA scans per patient was 4.8 ± 1.2. The imaging intervals were consistent with the follow-up protocol, with no significant difference in the average number of scans per year between the two groups (P = 0.215). Measurement of the true and false lumens at the primary entry tear and T12 levels is shown in Figure 1; Figure 2 demonstrates a typical example of aortic adverse remodeling.

Clinically and surgically relevant variables demonstrating significant intergroup differences were incorporated as predictors, including true and false lumen diameters at the primary entry tear and at the T12 vertebral level, the extent of false lumen involvement, patency of the false lumen, the number of branch vessels originating from the false lumen, and the timing of surgery. These variables were used as independent predictors in a logistic regression model with post-TEVAR aortic remodeling status (positive/negative) as the outcome. The model demonstrated excellent calibration (HL χ² = 4.353, P = 0.824).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis identified the following independent predictors of aortic remodeling status after TEVAR. Larger false lumen diameters at both the primary entry tear [odds ratio (OR): 1.561, 95%CI: 1.197-2.035; P = 0.001] and the T12 level (OR: 1.564, 95%CI: 0.894-1.766; P = 0.001) were significant risk factors for adverse remodeling. Conversely, larger true lumen diameters at both locations were associated with a reduced risk, acting as protective factors (primary entry: OR: 0.931; T12: OR: 0.902), although these associations were not statistically significant (P = 0.448 and P = 0.317, respectively).

Regarding the extent of false lumen involvement, using thoracic aorta involvement as the reference, extension to the thoracoabdominal aorta was identified as the strongest significant risk factor for adverse remodeling (OR: 11.751, 95%CI: 9.841-15.612; P = 0.001). Involvement limited to the thoracic aorta itself demonstrated a protective effect (OR: 0.925, 95%CI: 0.614–0.831; P = 0.015). Patency of the false lumen was also a strong and significant risk factor (OR: 5.639, 95%CI: 4.372-8.181; P = 0.004).

In terms of surgical timing, with subacute phase intervention as the reference, acute phase intervention was a significant risk factor (OR: 1.175, 95%CI: 0.886–1.925; P = 0.045). Both subacute and chronic phase interventions were associated with a protective effect (OR: 0.224 and OR: 0.287, respectively), although these results were not statistically significant. The number of branch vessels originating from the false lumen was not a significant predictor (OR: 1.595, P = 0.366) (Table 3).

| Variable1 | β | SE | Wald χ² | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| True lumen diameter at primary entry tear | -0.071 | 0.094 | 0.576 | 0.931 | 0.774-1.120 | 0.448 |

| False lumen diameter at primary entry tear (mm) | 0.445 | 0.135 | 10.820 | 1.561 | 1.197-2.035 | 0.001 |

| True lumen diameter at T12 level (mm) | -0.103 | 0.103 | 1.000 | 0.902 | 0.736-1.104 | 0.317 |

| False lumen diameter at T12 level (mm) | 0.589 | 0.165 | 12.807 | 1.564 | 0.894-1.766 | 0.001 |

| False lumen involvement: Thoracic aorta | -0.314 | 0.075 | 7.125 | 0.925 | 0.614-0.831 | 0.015 |

| False lumen involvement: Suprarenal abdominal aorta | -0.369 | 0.751 | 0.242 | 0.691 | 0.159-3.011 | 0.023 |

| False lumen involvement: Thoracoabdominal aorta | 8.545 | 12.254 | 24.687 | 11.751 | 9.841-15.612 | 0.001 |

| Branch vessels from false lumen | 0.467 | 0.517 | 0.816 | 1.595 | 0.579-4.390 | 0.366 |

| Patency of false lumen | 1.730 | 0.721 | 5.751 | 5.639 | 4.372-8.181 | 0.004 |

| Acute phase intervention | 1.476 | 0.284 | 5.118 | 1.175 | 0.886-1.925 | 0.045 |

| Subacute phase intervention | -1.497 | 1.104 | 1.839 | 0.224 | 0.026-1.947 | 0.175 |

| Chronic phase intervention | -1.248 | 0.856 | 1.125 | 0.287 | 0.014-1.537 | 0.145 |

To evaluate the discriminatory performance of our prediction model for aortic adverse remodeling, we constructed a ROC curve (Figure 3). The model demonstrated excellent discriminatory ability, with an AUC of 0.968 (95%CI: 0.942-0.994; P < 0.001).

Current research on aortic adverse remodeling following TEVAR for TBAD remains dynamic. Extensive investigations have examined hemodynamic parameters, biomarkers, and genetic features to identify key determinants of this process[6-8]. For example, high-resolution MRI and computational fluid dynamics analyses have shown that aberrant hemodynamic conditions-characterized by altered flow velocities and pressure distributions after TEVAR-may play a significant role in adverse remodeling[6,7]. Other studies have focused on biomarkers, such as inflammatory responses and matrix metalloproteinase activity, to clarify the molecular mechanisms driving dissection progression[8]. Addi

Current methodologies for assessing aortic morphological changes after TEVAR remain poorly standardized. Various methodologies are currently employed: Some researchers utilize the true lumen index [true lumen diameter/(true lumen diameter + false lumen diameter)] and false lumen index [FLI = false lumen diameter/(true lumen diameter + false lumen diameter)][12], while others rely on comparisons of pre- and postoperative maximum aortic diameter, true and false lumen cross-sectional areas, volumetric measurements, or total aortic volume[13]. Several factors informed our selection of endpoint measures: First, changes in aortic true and false lumen diameters generally parallel those observed in area and volume. Second, area and volumetric measurements require more complex protocols and are subject to greater observer variability. Third, diameter-based measurements remain the clinically preferred parameter for routine decision-making. Based on these considerations, our study used serial diameter measurements of the true and false lumens along with false lumen thrombosis status as key morphological endpoints. Notably, true lumen diameters at both the primary entry tear and the T12 vertebral level showed a positive correlation with favorable aortic remodeling, whereas false lumen diameters at these sites were inversely correlated with positive remodeling outcomes.

This study further established the extent of dissection involvement as a significant determinant of aortic remodeling following TEVAR. More extensive dissection was correlated with less favorable remodeling outcomes, likely due to the presence of multiple entry and re-entry tears in complex dissections that may not be completely treated by TEVAR alone[14]. For TBAD patients with extensive involvement, staged procedures or combined abdominal endograft deployment should be considered to improve outcomes[15]. Notably, left subclavian artery revascularization showed no significant association with remodeling patterns—a finding that contrasts with some previous reports[16]. This discrepancy may be explained by the limited sample size restricting subgroup analyses, highlighting the need for large-scale multicenter studies to clarify this clinical inconsistency. In summary, post-TEVAR aortic remodeling in TBAD is multifactorial. Key predictors of adverse remodeling include true and false lumen diameters, extents of false lumen involvement, number of branch vessels originating from the false lumen, and timing of intervention. Comprehensive preoperative assessment is essential to facilitate tailored management strategies, optimize surgical efficacy, and improve long-term outcomes.

This validated risk prediction model identifies aortic adverse remodeling with high accuracy using routinely available clinical parameters. Pan-aortic false lumen involvement is the strongest predictor (11.7-fold increased risk). The tool enables preoperative risk stratification to guide tailored TEVAR strategies and improve long-term outcomes.

| 1. | Pape LA, Awais M, Woznicki EM, Suzuki T, Trimarchi S, Evangelista A, Myrmel T, Larsen M, Harris KM, Greason K, Di Eusanio M, Bossone E, Montgomery DG, Eagle KA, Nienaber CA, Isselbacher EM, O'Gara P. Presentation, Diagnosis, and Outcomes of Acute Aortic Dissection: 17-Year Trends From the International Registry of Acute Aortic Dissection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66:350-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 507] [Cited by in RCA: 827] [Article Influence: 75.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nienaber CA, Kische S, Ince H, Fattori R. Thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair for complicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:1529-1533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanna JM, Andersen ND, Ganapathi AM, McCann RL, Hughes GC. Five-year results for endovascular repair of acute complicated type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59:96-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Famularo M, Meyermann K, Lombardi JV. Aneurysmal degeneration of type B aortic dissections after thoracic endovascular aortic repair: A systematic review. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66:924-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Erbel R, Aboyans V, Boileau C, Bossone E, Bartolomeo RD, Eggebrecht H, Evangelista A, Falk V, Frank H, Gaemperli O, Grabenwöger M, Haverich A, Iung B, Manolis AJ, Meijboom F, Nienaber CA, Roffi M, Rousseau H, Sechtem U, Sirnes PA, Allmen RS, Vrints CJ; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2873-2926. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2374] [Cited by in RCA: 3213] [Article Influence: 267.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sengupta S, Zhu Y, Hamady M, Xu XY. Evaluating the Haemodynamic Performance of Endografts for Complex Aortic Arch Repair. Bioengineering (Basel). 2022;9:573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Canaud L, Gandet T, Sfeir J, Ozdemir BA, Solovei L, Alric P. Risk factors for distal stent graft-induced new entry tear after endovascular repair of thoracic aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69:1610-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Radak D, Djukic N, Tanaskovic S, Obradovic M, Cenic-Milosevic D, Isenovic ER. Should We be Concerned About the Inflammatory Response to Endovascular Procedures? Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2017;15:230-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yang CP, Hsu CP, Chen WY, Chen IM, Weng CF, Chen CK, Shih CC. Aortic remodeling after endovascular repair with stainless steel-based stent graft in acute and chronic type B aortic dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1600-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim KM, Donayre CE, Reynolds TS, Kopchok GE, Walot I, Chauvapun JP, White RA. Aortic remodeling, volumetric analysis, and clinical outcomes of endoluminal exclusion of acute complicated type B thoracic aortic dissections. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:316-24; discussion 324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Giles KA, Beck AW, Lala S, Patterson S, Back M, Fatima J, Arnaoutakis DJ, Arnaoutakis GJ, Beaver TM, Berceli SA, Upchurch GR, Huber TS, Scali ST. Implications of secondary aortic intervention after thoracic endovascular aortic repair for acute and chronic type B dissection. J Vasc Surg. 2019;69:1367-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Huang X, Huang L, Sun L, Xu S, Xue Y, Zeng Q, Guo X, Peng M. Endovascular repair of Stanford B aortic dissection using two stent grafts with different sizes. J Vasc Surg. 2015;62:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Patterson BO, Cobb RJ, Karthikesalingam A, Holt PJ, Hinchliffe RJ, Loftus IM, Thompson MM. A systematic review of aortic remodeling after endovascular repair of type B aortic dissection: methods and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:588-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nienaber CA, Clough RE. Management of acute aortic dissection. Lancet. 2015;385:800-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 482] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Thommen V, Gualandro DM, Puelacher C, Durak K, Glarner N, Cardozo FAM, Bolliger D, Caramelli B, Mujagic E, Mueller C; BASEL-PMI Investigators. Prevalence, phenotypes, and long-term outcomes of cardiac complications after arterial vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2025;S0741-5214(25)01600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Song Y, Liu L, Jiang B, Wang Y. Risk factors of cerebral complications after Stanford type A aortic dissection undergoing arch surgery. Asian J Surg. 2022;45:456-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/