INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular (CV) diseases continue to dominate global mortality charts, responsible for nearly 18.6 million deaths annually[1]. Despite major advances in diagnostics, therapeutics, and risk stratification, acute coronary syndromes (ACS), heart failure (HF), and cardiogenic shock still present high morbidity and mortality rates, particularly in critically ill patients where prognosis is difficult to estimate in real time[2]. Conventional cardiac biomarkers, such as troponins, B-type natriuretic peptides, and C-reactive protein, have provided clinical value for decades, but their limited sensitivity in early or evolving disease, and their inability to reflect the full spectrum of pathophysiological processes (e.g., hemodynamic instability, metabolic disarray, chronic inflammation) has prompted the search for novel biomarkers. The recently published review by Bokhari et al[3] offers a timely synthesis of this evolving field, highlighting emerging molecular players like growth differentiation factor-15, suppression of tumorigenicity 2, osteopontin, adrenomedullin, galectin-3, and various microRNAs. These biomarkers provide insight into endothelial dysfunction, oxidative stress, neurohormonal activation, and myocardial injury. Bokhari et al[3] also advocate for a multiple-marker strategy, integrating traditional and novel biomarkers, to improve risk stratification and early diagnosis.

DPP3: FROM CIRCULATING BIOMARKER TO THERAPEUTIC TARGET

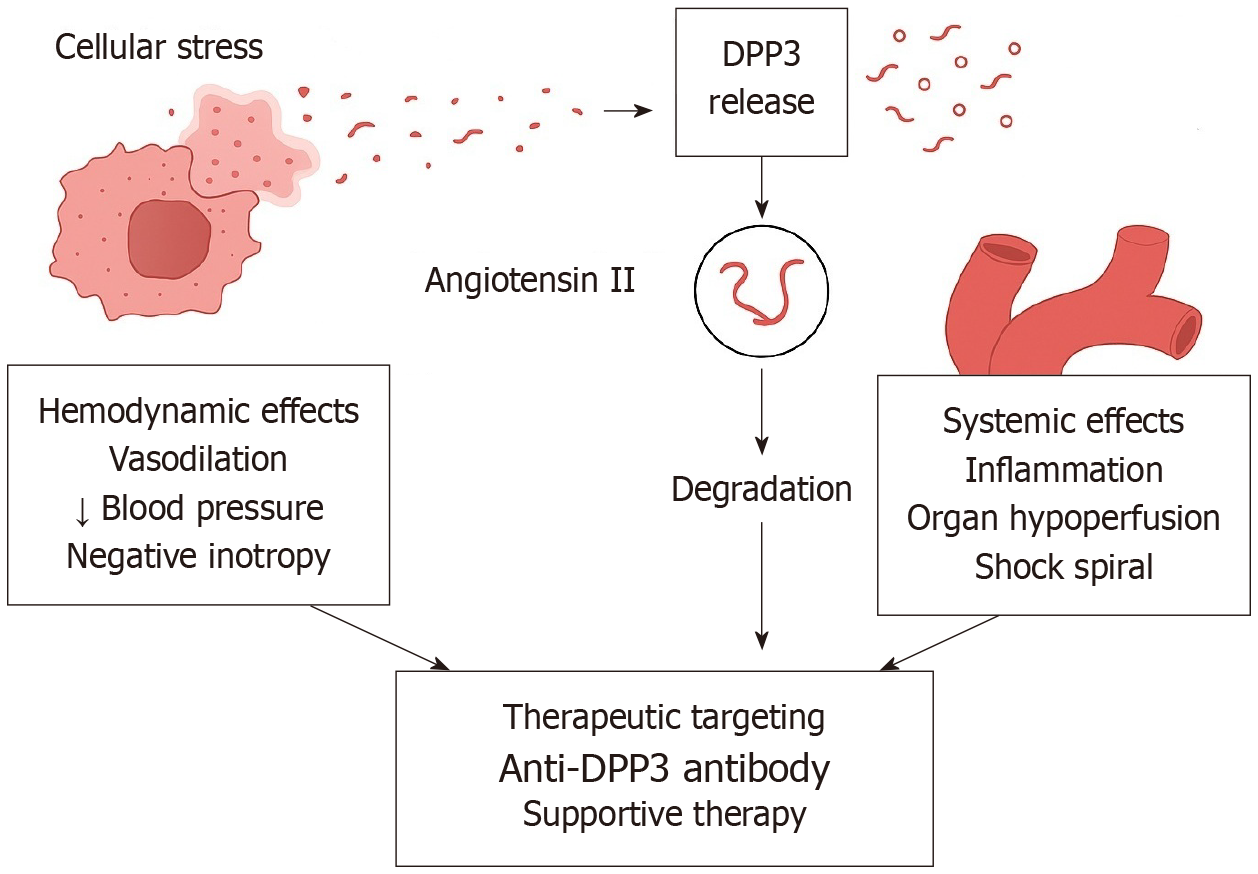

Among the emerging CV biomarkers highlighted in recent literature, dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3) stands out for its dual role, offering mechanistic insight as well as prognostic power in CV diseases. DPP3 is a zinc-dependent intracellular aminopeptidase that hydrolyzes bioactive peptides including angiotensin II (Ang II), enkephalins, and endorphins[4]. Under physiologic conditions, it resides within the cytosol; however, during states of acute cellular damage, such as ischemia, sepsis, or trauma, circulating DPP3 (cDPP3) is released into the bloodstream. Once in circulation, cDPP3 can degrade Ang II, as well as other oligopeptides, resulting in reduced Ang II receptor type 1 activation and subsequent modulation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS)[5,6]. This process promotes vasodilation and myocardial depression, primarily through its effects on vasoactive peptide metabolism and organ perfusion[7]. Mechanistic studies in both animal models and critically ill patients have demonstrated that elevated cDPP3 exerts negative inotropic effects and exacerbates circulatory failure through suppression of Ang II signaling[8,9]. This positions cDPP3 not only as a biomarker of cellular distress, but also as a potential pathophysiological effector (Figure 1). Recent high-impact studies, including that of Wenzl et al[10], have identified cDPP3 as an independent predictor of cardiogenic shock and mortality in ACS. In this landmark study, which included 4787 patients enrolled in the multicenter SPUM-ACS cohort, elevated cDPP3 at admission and 12-24 hours post-presentation was independently associated with a significantly increased risk of in-hospital cardiogenic shock, 30-day mortality, and 1-year mortality, even after adjustment for clinical variables and the GRACE 2.0 risk score. Most striking was the finding that persistently elevated cDPP3 at 24 hours conferred a 13.4-fold higher 30-day mortality risk, compared to patients whose levels normalized. This dynamic behavior makes cDPP3 particularly attractive as a monitoring tool, capturing the trajectory of illness more accurately than static biomarkers. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging data further linked cDPP3 trajectories to infarct size, suggesting it may reflect both myocardial damage and systemic response. Unlike many biomarkers that passively reflect tissue injury, cDPP3 is actively involved in the pathogenesis of hemodynamic collapse, placing it at the intersection of diagnostic and therapeutic innovation. Persistently elevated cDPP3 confers a markedly increased risk of death, suggesting its utility as a prognostic biomarker in acute cardiac settings[11]. In worsening HF, higher DPP3 levels are associated with more severe disease and altered RAAS activity, potentially counteracting the protective ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/Mas pathway[8]. Additionally, DPP3 has been implicated in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by promoting mitophagy and intrinsic apoptosis; its downregulation may confer cardioprotection in experimental models[12]. Conversely, in diabetic mouse models, recombinant cDPP3 administration has shown cardio- and reno-protective effects, partly by degrading cytotoxic complement-derived peptides[13]. Additional studies have validated the prognostic power of cDPP3 in other settings, including septic and vasodilatory shock, underscoring its broad relevance[4,14]. Mechanistically, cDPP3 acts as a myocardial depressant factor. Several preclinical models suggest that exogenous cDPP3 administration induces acute myocardial depression and renal dysfunction, while experimental neutralization of cDPP3 (e.g., with the monoclonal antibody procizumab) has been shown to reverse these deleterious effects, rapidly improve hemodynamics, reduce oxidative stress and partially restore cardiac function. These findings raise the possibility that cDPP3 may evolve from a passive biomarker into a potential therapeutic target[8,11]. This concept appears particularly relevant in the setting of cardiogenic shock, where conventional interventions such as vasopressors and inotropes often fail to reverse the downward spiral of multiorgan failure. Nonetheless, it is important to emphasize that such data remain confined to preclinical or early translational studies, and clinical efficacy in humans has not yet been established. On this basis, patients presenting acute HF, cardiogenic shock, or ACS who show markedly elevated cDPP3 are most likely to benefit from targeted therapies, whereas those with stable or chronic HF without significant cDPP3 elevation, or with preserved hemodynamics, may derive limited benefit and face unintended adverse effects. Interestingly, beyond its detrimental role in acute circulatory collapse, exogenous DPP3 administration has also demonstrated context-dependent protective effects in chronic disease models by mitigating the harmful impact of excessive Ang II[15]. For example, in preclinical studies of chronic HF, a four-week regimen of intravenous DPP3 infusion attenuated Ang II–induced cardiac fibrosis and conferred antifibrotic, cardioprotective benefits[16]. Together, these observations underscore the complex and context-specific biology of DPP3 and highlight the need for cautious interpretation. Rigorous clinical trials are required before cDPP3-directed therapies can be translated into routine practice. The notable side effects associated with emerging therapies that target cDPP3 are not yet fully characterized in humans, as clinical data remain limited and most evidence is derived from preclinical models. In animal studies, cDPP3 inhibition has been associated with decreased renal blood flow and potential alterations in systemic hemodynamics, likely due to increased Ang II activity and reduced degradation of vasoactive peptides[15]. This may theoretically predispose to hypertension, renal hypoperfusion, or fluid overload in susceptible patients, especially those with underlying HF or compromised renal function[7,11]. Elderly patients and those with multiple comorbidities who might receive cDPP3 inhibitor therapies will likely require heightened monitoring and individualized precautions, as age-related decline in renal function, altered pharmacodynamics, and the presence of comorbidities could amplify the risk of adverse effects from cDPP3 inhibition, including acute kidney injury and blood pressure instability[17]. Additionally, because DPP3 is involved in the degradation of multiple peptides, including endogenous opioids, its inhibition may lead to off-target effects such as neurohormonal imbalances and alterations in inflammatory or oxidative stress pathways. However, these potential effects have not been systematically reported in murine models. No specific immunogenicity or hypersensitivity reactions have been described in the available preclinical literature, but these remain theoretical risks with monoclonal antibody therapies. Despite its promise, several practical barriers currently limit the clinical translation of cDPP3. Commercial assays for its measurement are not yet widely available, and there is a lack of standardized platforms or universally accepted cut-off thresholds for risk stratification. Moreover, most current techniques are laboratory-based and not adapted for real-time bedside testing, which restricts their utility in acute care settings where rapid decision-making is critical. Overcoming these methodological hurdles will be essential before cDPP3 can be reliably integrated into multimarker panels or used to guide targeted therapies.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of dipeptidyl peptidase 3 release during cellular stress and its downstream effects.

Cellular stress (e.g., ischemia, acute coronary syndrome, shock) triggers the release of intracellular dipeptidyl peptidase 3 (DPP3) into the plasma. Extracellular DPP3 degrades angiotensin II, leading to impaired renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system signaling. This cascade results in hemodynamic effects such as vasodilation, hypotension, and negative inotropy, as well as systemic consequences including inflammation, organ hypoperfusion, and progression toward a shock spiral. Potential therapeutic interventions include anti-cDPP3 antibodies and supportive therapies aimed at restoring hemodynamic stability and mitigating systemic damage. DPP3: Dipeptidyl peptidase 3.

CONCLUSION

As CV medicine increasingly embraces systems biology and precision medicine, cDPP3 has emerged as a distinctive biomarker that not only signals cellular distress but also actively contributes to hemodynamic deterioration by modulating vascular tone, cardiac contractility, and immune activation. Its dynamic behavior and strong prognostic value sets cDPP3 apart from conventional markers, and its mechanistic involvement suggests a dual clinical role: Providing early identification of high-risk patients while simultaneously offering a novel therapeutic target to improve outcomes. Challenges remain, including the need for standardized assay platforms, validated thresholds, and multicenter validation studies across diverse CV phenotypes. Nonetheless, current evidence highlights cDPP3 as a compelling addition to the CV biomarker repertoire, offering both mechanistic insight and prognostic precision, with the potential to enhance early detection, personalized treatment, and therapeutic monitoring in acute HF, ACS, and cardiogenic shock.