Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.110861

Revised: July 17, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 190 Days and 13.8 Hours

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of mortality worldwide despite major advances in prevention and treatment. The odd-chain saturated fatty acid pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), primarily obtained from dairy fat, has been associated with cardiometabolic benefits. To summarize recent advances in understanding the role of pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) in CVD biology and risk, and to identify knowledge gaps and future research priorities. A narrative review was conducted, drawing on 115 PubMed-indexed studies on odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs) and cardiovascular outcomes, as well as illustrative mechanistic studies of C15:0. This narrative review synthesized evidence from approximately 115 PubMed-indexed studies on OCFAs and cardiovascular outcomes, along with mechanistic studies of C15:0, identified through targeted searches in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 2000 through May 2025.

Core Tip: Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), an odd-chain saturated fat concentrated in grass-fed dairy, is increasingly recognized as a “good” saturated fat with cardioprotective potential. Prospective cohorts and a recent meta-analysis show that individuals in the highest C15:0 quintile experience 12%-25% fewer cardiovascular events and approximately 14% less incident type 2 diabetes. Mechanistic studies reveal that C15:0 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta and AMP-activated protein kinase, lowers low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor α-driven inflammation, enhances insulin sensitivity, and repairs mitochondrial-endothelial function - findings that prompt calls to test dietary or supplemental C15:0 in randomized trials and to rethink blanket saturated-fat limits.

- Citation: Mercola J. Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) and cardiovascular disease: A narrative review. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(12): 110861

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i12/110861.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i12.110861

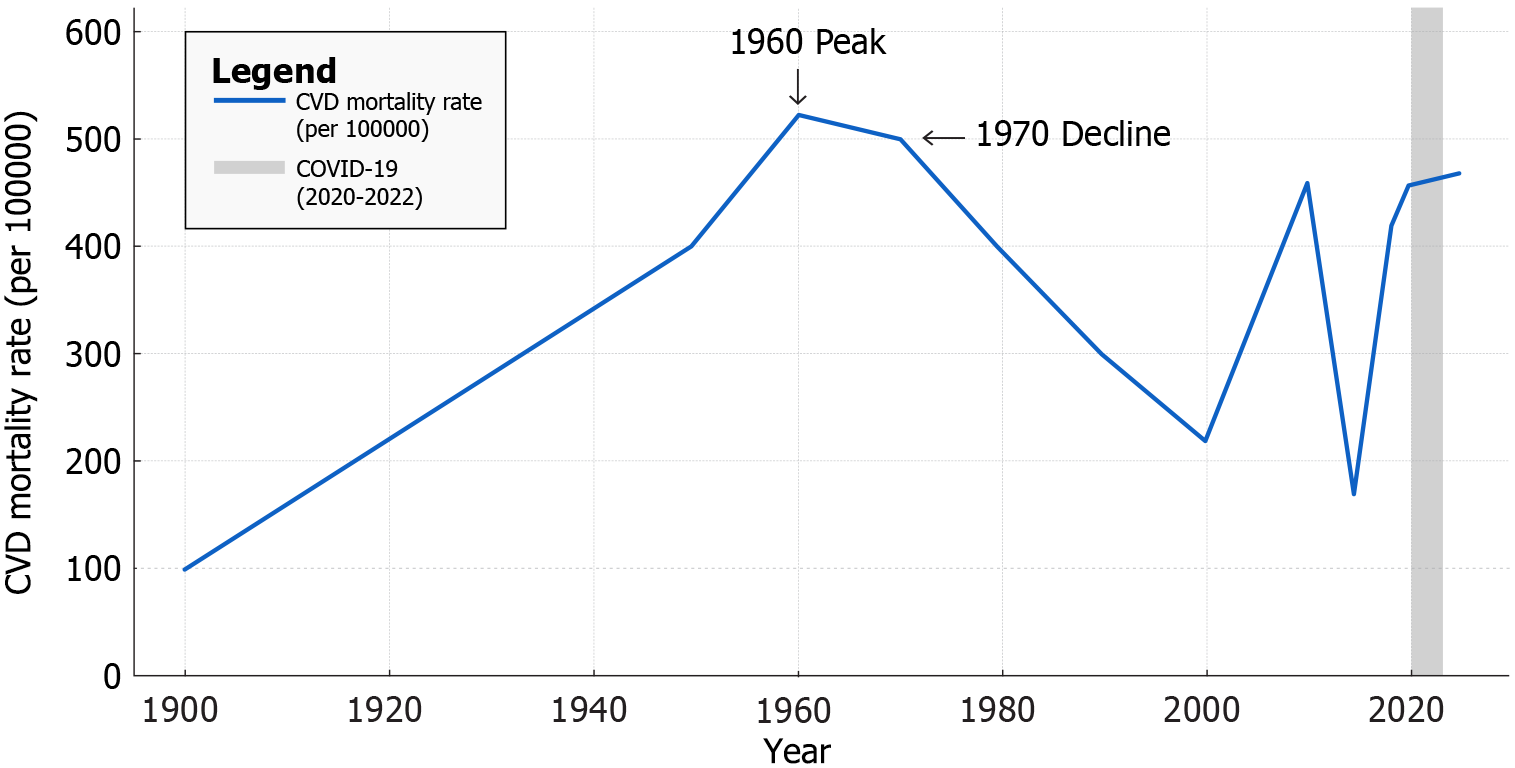

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) encompasses a range of heart and vascular conditions and has been the leading cause of death in the United States since 1921. By the mid-20th century, coronary heart disease (CHD) had reached epidemic proportions, but age-adjusted CVD mortality rates declined by about 60% from 1950 to 1999[1]. This remarkable reduction is attributed to advances in risk factor control and acute care improvements[2]. However, progress has stalled in recent years. Between 2010 and 2019, the United States CVD death rate fell modestly (456.6 per 100000 adults to 416.0 per 100000 adults) only to rise back to approximately 454.5 per 100000 by 2022 amid the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic[2]. CVD still accounts for about one in three United States deaths, reflecting an urgent need for novel preventive strategies alongside traditional approaches[1].

Dietary habits are central to CVD prevention. Historically, saturated fatty acids (SFAs) were targeted as a modifiable risk factor after early studies linked high intake of animal fats with elevated serum cholesterol and heart disease[3]. For decades, guidelines advised restricting all SFAs to improve lipid profiles and reduce CVD events[4]. This broad-brush approach has recently been reassessed as researchers recognize that individual fatty acids have diverse metabolic effects[4]. Despite decades of investigation, the link between total saturated fat intake and CVD remains hotly debated: Contemporary metaanalyses and guideline panels reach conflicting conclusions depending on study selection, background diet, and the nutrients that replace SFAs, highlighting that blanket saturationfat limits may be overly simplistic[3-6]. In particular, odd-chain SFAs (OCSFAs) such as pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) behave differently from the even-chain SFAs (ECSFAs) abundant in meat and tropical oils[7]. OCSFAs are fully hydrogenated fatty acids whose carbon backbone contains an odd number of atoms - most commonly C15:0 and heptadecanoic acid (C17:0). They arise chiefly from rumen microbial fermentation and, unlike the more prevalent ECSFAs, have been linked in cohort studies to lower risks of cardiometabolic disease[8,9].

Intriguingly, higher circulating levels of these odd-chain fatty acids (OCFAs) have been associated with lower risks of CVD and metabolic diseases in epidemiological studies[7]. Yet not all data are supportive: Null findings have been reported in the United Kingdom Biobank and the Danish Diet, Cancer and Health Study, and a recent pooled analysis described a U-shaped association, suggesting that any cardioprotection from C15:0 may plateau - or even reverse - at very high exposures[10,11]. These findings raise the question of whether specific fatty acids like C15:0 could be cardioprotective, countering the conventional paradigm that saturated fat is uniformly harmful[12]. C15:0 is being investigated as a bioactive lipid with potential health benefits, even prompting suggestions that it may represent an essential nutrient for metabolic health[13]. Nevertheless, these inverse associations come from observational cohorts that are predominantly Western, usually depend on a single baseline biomarker, and remain vulnerable to residual confounding, dietsubstitution effects, and reverse causation - limitations that temper causal inference and reinforce the need for randomized trials[5,14,15].

Does greater dietary intake or circulating concentration of C15:0 lower the incidence of CVD compared with lower exposure? This narrative review synthesizes epidemiological and experimental evidence addressing this question[16]. The paper provides historical context on CVD incidence and outcomes to frame the magnitude of the problem[1]. It then synthesizes evidence on dietary sources and biomarkers of C15:0[17], prospective studies linking C15:0 to cardiovascular events, and mechanistic insights spanning lipoprotein modulation, inflammation, insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial function, and vascular effects[18]. The goal is to integrate epidemiologic and experimental data to assess how C15:0 may influence atherosclerosis and cardiometabolic risk[18].

A narrative synthesis was chosen because the current evidence spans heterogeneous epidemiological designs, mechanistic experiments, and emerging translational data that cannot yet be pooled quantitatively; this format allows integration of disparate findings and flexible identification of crosscutting knowledge gaps. Given the nonsystematic design of this review, sources were selected to illustrate key concepts rather than exhaustively cover the literature. No formal meta-analysis was conducted; instead, emphasis is placed on consistency of findings across high-quality cohorts and mechanistic studies. Limitations inherent to a narrative review - including potential selection bias and subjective emphasis - are acknowledged when interpreting the results.

In highlighting recent advances, this review aims to clarify whether increasing C15:0 intake or blood levels might confer cardiovascular benefits and how this knowledge could refine dietary guidelines[19]. It also delineates open questions to guide future research[20]. By bridging population studies with biochemical and clinical insights, the review evaluates the emerging paradigm that not all saturated fats are equal, and that C15:0 may in fact be a “good” saturated fat for cardiometabolic health[7].

To identify relevant studies for this narrative review, targeted searches were conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from January 2000 through May 2025. The search strategy employed Boolean operators to combine terms related to odd-chain fatty acids and cardiometabolic outcomes, as follows: ("odd-chain fatty acids" OR "odd chain fatty acids" OR "OCFA" OR "pentadecanoic acid" OR "C15:0" OR "heptadecanoic acid" OR "C17:0" OR "margaric acid") AND ("cardiovascular disease" OR "CVD" OR "heart disease" OR "coronary heart disease" OR "atherosclerosis" OR "cardiometabolic risk" OR "metabolic syndrome" OR "type 2 diabetes" OR "insulin resistance"). Additional filters were applied for English-language, peer-reviewed articles, with a preference for human cohort studies, intervention trials, and mechanistic investigations (including animal and in vitro models where relevant to biological pathways). No formal inclusion/exclusion criteria or risk-of-bias tools were predefined, as this is a narrative synthesis rather than a systematic review; however, reference lists of key articles were hand-searched to identify additional sources, and emphasis was placed on highly cited or recent publications to ensure a balanced overview of the evidence. This approach yielded approximately 150 unique records, which were screened by title and abstract for relevance, with full texts reviewed for about 60 studies ultimately informing the synthesis. Formal grey literature searches were not performed. Higher circulating C15:0 levels are consistently associated with lower incident CVD and type 2 diabetes (T2D) in prospective cohorts. Experimental studies demonstrate that C15:0 favorably modulates atherogenic lipoproteins, exerts anti-inflammatory effects [e.g., lowering interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)], enhances insulin sensitivity via AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation, and supports mitochondrial function. These actions collectively may translate into improved endothelial function, blood pressure regulation, and overall cardiac health. C15:0 is emerging as a potentially cardioprotective nutrient. Recognizing C15:0's distinct biological profile could inform more nuanced dietary recommendations and spur trials of C15:0 supplementation to test causality in cardiometabolic disease prevention.

CVD incidence and mortality in the United States have undergone striking transitions over the past century[1]. In 1900, infectious diseases dominated mortality statistics while heart disease was a relatively uncommon cause of death[21]. By 1950, however, CVD - especially CHD and stroke - had surged to become the nation’s leading health threat[21]. Sedentary lifestyles, cigarette smoking, and diets rich in animal fats contributed to an epidemic of atherosclerosis by mid-century[22]. The age-adjusted annual death rate from heart disease peaked around 1960[23]. Heart disease and stroke together accounted for approximately 40% of all United States deaths by the 1970s[23]. This burden spurred public health action and research that ushered in the modern cardiovascular revolution[24].

From the 1970s through the 2010s, age-adjusted CVD mortality declined dramatically in the United States and most high-income countries[23]. Between 1980 and 2014, overall CVD death rates fell by roughly 50%-70% in many populations[23]. In the United States, improvements in control of blood pressure and cholesterol, reductions in smoking, plus advances in acute coronary care (e.g., defibrillation, coronary care units, revascularization) drove this decline[25]. For instance, the age-standardized heart disease death rate in the United States dropped from approximately 520 per 100000 in 1968 to approximately 168 per 100000 by 2015[23]. By the 1990s, some predicted that CVD might cease to be the leading cause of death if trends continued[26]. However, in the past decade these gains have leveled off, and in some demographics reversed, due to factors like the obesity-diabetes epidemic and disparities in risk factor control[27].

Recent data underscore the persistent and evolving challenge of CVD. From 2010 to 2019, the national age-adjusted CVD mortality rate declined modestly, from 456.6 per 100000 to 416.0 per 100000[28]. Then, coincident with the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-2021), CVD death rates rose sharply, by 9.3% through 2022, effectively erasing a decade of progress[29]. An estimated 228000 excess CVD deaths occurred in 2020-2022 beyond pre-2020 trends[29]. Possible contributors include direct cardiac complications of COVID-19[30], delays in care, and worsened risk factor profiles during pandemic lockdowns[31]. Consequently, in 2022 the United States CVD mortality rate was back to roughly the level of 2010[29]. Heart disease remains the leading cause of death[29], with about 20.1 million adults in the United States having coronary artery disease and nearly 928000 Americans expected to suffer a myocardial infarction in 2025, according to recent American Heart Association data[32] (Figure 1).

This historical perspective highlights that while CVD is partly controllable through public health measures, it continues to impose an enormous burden. Against this backdrop, attention has turned to novel preventive avenues - including nutritional strategies - to complement traditional risk factor management.

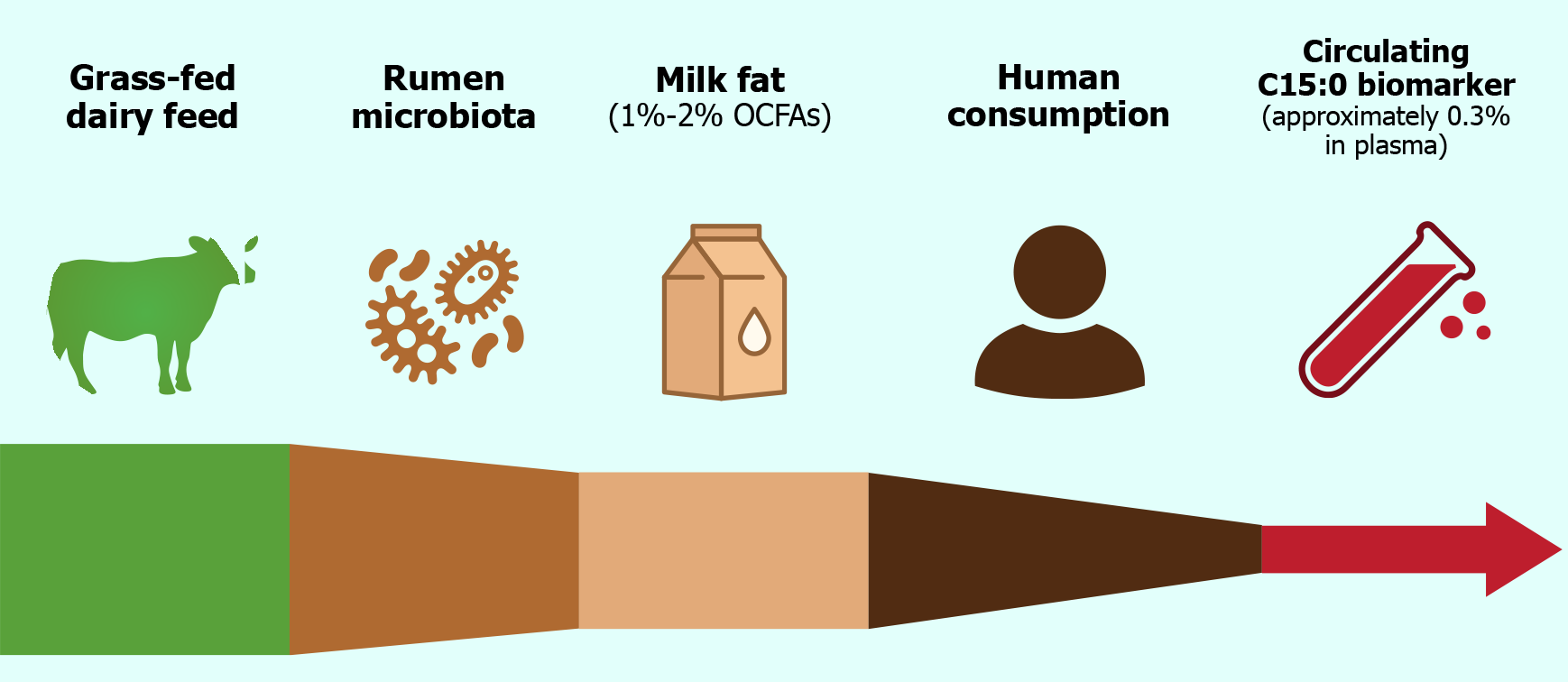

The primary dietary sources of C15:0 are ruminant fats, especially dairy products such as whole milk, butter, cheese, and yogurt[33]. Bovine milk fat typically contains on the order of 1%-2% OCFAs by weight, of which C15:0 and C17:0 are the most prevalent[33]. These OCFAs originate in ruminant animals from the unique metabolism of gut microbiota in the rumen. Fermentation of dietary fiber in ruminants produces propionate, a three-carbon SCFA.

Rumen microbes incorporate propionyl-CoA, derived from propionate, as a primer in fatty acid synthesis, yielding OCFAs that accumulate in ruminant tissues and milk[34]. C15:0 and C17:0 formed via this pathway are thus incorporated into dairy fat and, to a lesser extent, ruminant meat fat[34]. Besides dairy, minor sources of C15:0 include certain types of fish and some plants, but these contributions are quantitatively small[35]. For most individuals, habitual intake of C15:0 is largely a function of dairy fat consumption (Figure 2)[35]. It is crucial to recognize that not all dairy products contain high levels of C15:0[34]. Notably, reduced-fat and skim milk contain much less C15:0 than full-fat dairy, since this fatty acid resides in the milk fat fraction[36]. Milk from ruminants fed a grass-dominant diet also has significantly higher C15:0 content compared to those fed primarily on grains, as grass promotes greater synthesis of this fatty acid by the rumen microbiota[17].

Given its dietary origin, circulating C15:0 has been investigated as an objective biomarker of dairy fat intake[37]. C15:0 can be measured in blood compartments such as plasma phospholipids, cholesterol esters, or red blood cell (RBC) membranes, and reflects medium-term intake (weeks to months)[37]. Epidemiological studies validate C15:0 as a marker of dairy consumption: For example, serum C15:0 levels correlate with self-reported dairy food intake[38]. One study found that a 10-fold increase in full-fat dairy intake produced a proportional increase in plasma C15:0 percentage[38]. Moreover, interventions exchanging dairy fat for other fats result in corresponding changes in circulating C15:0[39]. Together, these observations establish C15:0 as a robust biomarker for recent dairy fat intake, more reliable than self-reported diet alone[37]. This has enabled nutritional epidemiologists to assess associations between “dairy signatures” in the blood and disease outcomes, independent of confounding by other dairy components[38].

Interestingly, humans also have limited endogenous sources of OCFAs[33]. It has been proposed that the α-oxidation of phytanic acid yield odd-chain products, and that gut microbial production of propionate might serve as a substrate for de novo synthesis of C15:0 and C17:0 in the liver[40]. Indeed, experimentally, propionate can be incorporated into OCFAs in mammals[41]. However, the quantitative contribution of this pathway in humans appears to be small under typical conditions. A controlled feeding study published in 2021 found that increasing dietary fiber to boost colonic propionate did not significantly raise circulating C15:0 or C17:0 levels[42]. This suggests that, unless extremely high fiber or direct propionate supplementation is present, endogenous production plays a minor role compared to direct dietary intake. Consistent with this, the ratio of C15:0 to C17:0 in human plasma (approximately 1:2) differs from the ratio in dairy fat (approximately 2:1), hinting that some metabolic processing or selective oxidation of these fatty acids occurs after ingestion[43]. Overall, C15:0 is best regarded as an exogenous nutrient obtained from ruminant fat, and its presence in human tissues serves as a fingerprint of dairy fat consumption[33].

From a nutritional standpoint, C15:0 intake has declined in many populations due to shifts toward low-fat dairy and plant-based diets[44]. For example, a population-wide decrease in whole milk and butter consumption over recent decades has corresponded with a measurable decline in average circulating C15:0 levels[45]. This reduction raises questions about potential unintended health impacts of broadly eliminating OCFAs from the diet - an issue explored further in later sections[13]. First, we examine epidemiologic studies that have related C15:0 status to cardiovascular outcomes[18].

A growing body of prospective cohort studies indicates that people with higher circulating C15:0 experience fewer cardiovascular events over time[46]. One of the earliest clues came from observations in the 1990s that high-fat dairy intake was not positively associated with CVD risk as expected, and in some cases appeared protective[47]. This prompted researchers to use C15:0 (and related fatty acids) as objective measures of dairy fat exposure in cohort analyses[47]. In recent years, consistent inverse associations have been reported between circulating C15:0 and incident CVD[7].

For instance, a 2021 analysis within a Swedish cohort of 4,150 adults found that higher baseline serum C15:0 was associated with significantly lower risk of first CVD events[46]. In multivariable-adjusted models, higher C15:0 was associated with lower incident CVD risk in a linear dose-response manner, with a hazard ratio of 0.75 per interquartile range (95% confidence interval: 0.61-0.93, P = 0.009), representing approximately a 25% lower risk[46]. This linear dose-response relationship suggests a graded benefit of higher C15:0 levels. Interestingly, in the same study, C15:0 showed a U-shaped relation with all-cause mortality with the nadir of mortality risk around the population median of 15:0[46]. This indicates a potential optimal range for C15:0, beyond which no further mortality advantage accrues.

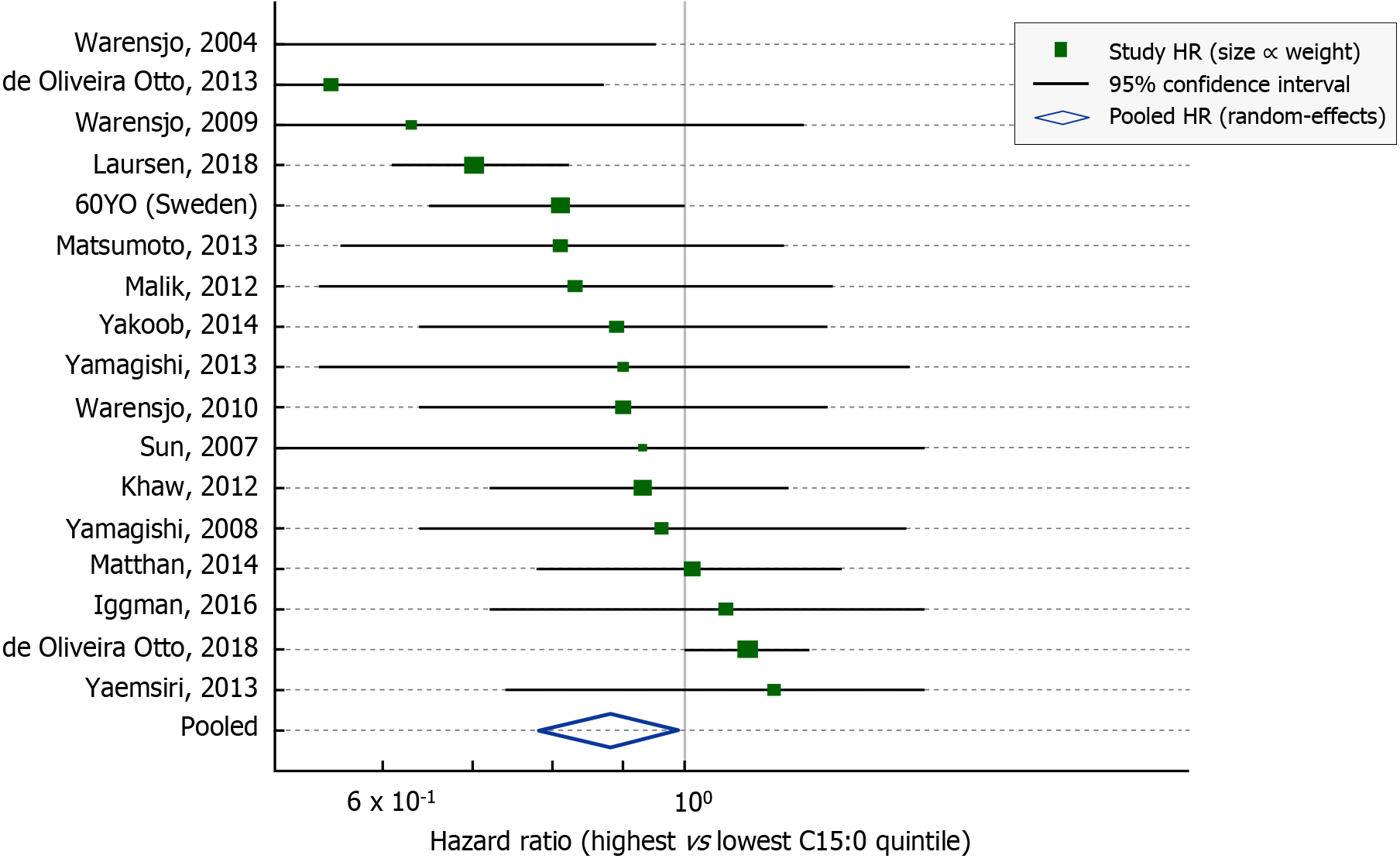

Beyond single cohorts, pooled analyses reinforce the protective association[43]. A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis combined 18 prospective studies (including the Swedish cohort above and others from Europe, the United States, Asia, and Australia) to evaluate dairy fat biomarkers and CVD outcomes[46]. In this meta-analysis by Trieu et al[46], individuals with high circulating 15:0 had an approximate 12% lower risk of total CVD events compared to those with low levels (pooled hazard ratio 0.88, 95% confidence interval: 0.82-0.94). These inverse associations persisted across diverse populations and were robust to adjustment for traditional risk factors (Figure 3)[7]. Notably, another biomarker of dairy, trans-palmitoleic acid showed no significant association with CVD in the same analysis, highlighting that the OCFAs specifically drive the observed benefit rather than all dairy-related fatty acids[43].

Furthermore, some studies suggest that higher 15:0 is particularly linked to lower CHD events[7]. In the Cardiovascular Health Study of older adults, each standard deviation increase in plasma 15:0 was associated with approximately 19% lower CHD risk[48]. An investigation in the multi-ethnic MESA cohort also found trends toward fewer coronary calcifications and cardiovascular events in those with greater OCFA levels, although results did not always reach statistical significance after full adjustments[10]. When examining stroke, the evidence is less abundant but generally consistent: A Dutch cohort reported that higher dairy fat biomarkers were associated with reduced risk of stroke, especially hemorrhagic stroke, but further confirmation is needed[5].

It is important to acknowledge that these observational findings do not prove causation[7]. Individuals with higher C15:0 might have other health-promoting behaviors or metabolic traits[11]. However, many analyses have adjusted for major dietary and lifestyle factors, and the consistency of inverse associations across independent cohorts lends credibility to a possible causal effect[7]. One strength of using C15:0 as an exposure is that it objectively captures dairy fat intake, circumventing errors in self-reported diet[49]. Interestingly, some results suggest that 15:0 might be more strongly related to lower heart failure (HF) risk as well[50]. In the Cardiovascular Health Study, only C15:0 and one very-long-chain SFA (nervonic acid) remained inversely associated with incident HF after accounting for competing risks. People with low circulating C15:0 had higher rates of developing HF over approximately 22 years, hinting at broader cardioprotective effects beyond atherosclerotic events[50].

One pathway through which C15:0 may influence CVD risk is by altering the circulating lipoprotein profile in a cardioprotective manner[45]. High levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and triglyceride-rich lipoproteins are established drivers of atherosclerosis[51]. Diets rich in ECSFAs typically raise LDL-C and can also elevate triglycerides in some cases, thereby promoting CVD[47]. OCFAs however, appear to have a different impact on lipid metabolism[45].

Animal studies provide evidence that C15:0 can attenuate dyslipidemia[16]. In a high-fat diet induced model of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, daily oral supplementation with C15:0 led to significantly lower total cholesterol and triglyceride levels compared to unsupplemented controls[52]. Treated animals had reduced hepatic steatosis and improved plasma lipid profiles despite ongoing high-fat feeding[52]. Similarly, in obese rodent models, C15:0 supplementation prevented further increases in serum cholesterol and triglycerides, suggesting a lipid-lowering effect[16]. These benefits may stem from enhanced fatty acid oxidation and improved hepatic lipid handling in the presence of C15:0[16].

Mechanistically, C15:0 is thought to act as a ligand for nuclear receptors that regulate lipid homeostasis[13]. Notably, C15:0 activates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta (PPARα/δ)[53]. PPARα is the molecular target of fibrate drugs and upregulates genes involved in fatty acid β-oxidation and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) production[54], while PPARδ broadly enhances lipid catabolism and may improve muscle fat burning[55]. Through PPARα activation, C15:0 could promote clearance of triglyceride-rich particles and raise HDL levels, akin to fibrate therapy[53]. PPARδ activation by C15:0 might increase systemic energy expenditure and reduce ectopic lipid deposition[55]. Indeed, gene expression studies in cell models confirm that C15:0 upregulates pathways of lipid oxidation and downregulates lipogenesis markers in hepatocytes[53].

Human data on C15:0’s direct effects on blood lipids are still emerging[45]. Cross-sectional analyses have found that individuals with higher circulating 15:0 tend to have modestly higher HDL-C and lower triglycerides, although these associations can be confounded by overall diet quality[18]. In one study of healthy women, erythrocyte membrane C15:0 was inversely correlated with fasting triglyceride levels and positively correlated with HDL-C, after adjusting for body mass index (BMI) and other factors[45]. This pattern - lower triglycerides and higher HDL - is consistent with an anti-atherogenic profile[43]. LDL-C associations have been less clear, with some analyses showing no significant correlation between OCFAs levels and LDL-C[18]. Importantly, raising ECSFA intake typically elevates LDL-C, but raising OCFAs intake (through dairy foods) does not appear to have the same hypercholesterolemic effect, possibly due to concurrent nutrients in dairy or unique metabolism of these fats[45].

Recent clinical trial evidence adds insight. A 12-week randomized trial in young adults with overweight tested a purified C15:0 supplement (100 mg/day) vs placebo. By study end, those receiving C15:0 had significantly increased circulating C15:0 levels (as expected) and showed trends toward improved lipid parameters. Notably, participants who achieved higher plasma C15:0 concentrations (> 5 µg/mL) experienced reductions in non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides compared to those with lower levels. Although changes did not reach statistical significance in the small sample, the directions were favorable and consistent with animal findings[16]. No adverse effects on LDL-C were observed, suggesting that isolated C15:0 does not raise LDL the way palmitate does. The trial also reported improved total cholesterol-to-HDL ratios in the C15:0 group, hinting at a shift toward cardioprotective lipid distributions[45].

Chronic low-grade inflammation and endothelial dysfunction are central in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis[56]. Another biologic role of C15:0 that may underlie its cardioprotective associations is its ability to dampen inflammatory pathways and preserve endothelial function. Evidence from in vivo models and cell-based systems indicates that C15:0 exerts broad anti-inflammatory effects[57].

Venn-Watson et al[58] first demonstrated that C15:0 supplementation can reduce systemic inflammation in mammals. In their study, obese mice given C15:0 for 12 weeks showed marked attenuation of pro-inflammatory cytokines compared to controls. A follow-up analysis reported that C15:0-treated animals had significantly lower circulating levels of monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-6, and TNFα[57]. These cytokines are key mediators of vascular inflammation: MCP-1 drives recruitment of monocytes into the arterial wall[59], IL-6 promotes hepatic C-reactive protein production and endothelial activation[60], and TNFα induces adhesion molecule expression on endothelium[61]. By lowering MCP-1, IL-6, and TNFα, C15:0 may interrupt the cycle of vascular inflammation that leads to plaque formation and instability[57]. The reduction in these cytokines with C15:0 was accompanied by lower levels of immunoglobulin G and other inflammation-related biomarkers, indicating a broad immunomodulatory effect[16].

Mechanistic insights into how C15:0 mediates anti-inflammatory actions point again to its role as a PPAR agonist[53]. PPARα and PPARδ activation is known to transrepress inflammatory gene expression in macrophages and endothelial cells, largely by antagonizing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells signaling[62]. C15:0’s activation of PPARα/δ likely leads to decreased production of cytokines and adhesion molecules[5]. Additionally, C15:0 has been shown to activate AMPK in various cell types[16]. AMPK activation can inhibit inflammatory responses and improve endothelial nitric oxide (NO) bioavailability by phosphorylating endothelial NO synthase (NOS)[63]. In a direct comparison study, C15:0 exhibited overlapping anti-inflammatory gene expression profiles with the omega-3 fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), but with even broader activity across certain cell systems[60]. For example, C15:0 at micromolar concentrations reduced the secretion of inflammatory mediators in human endothelial cell cultures challenged with endotoxin, comparable to or greater than the effects of EPA[64].

The implications for endothelial function are favorable. By lowering pro-inflammatory cytokines, C15:0 may reduce endothelial cell activation characterized by expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 and intercellular adhesion molecule-1[57]. This would result in fewer monocytes adhering and penetrating into the intima[64]. There is also preliminary evidence that C15:0 might directly support endothelial health. A study found that co-treating endothelial cells with C15:0 prevented some of the detrimental effects of palmitic acid (C16:0) exposure, such as oxidative stress and reduced NO production[13]. While direct vascular function studies in vivo are still limited, the anti-inflammatory profile of C15:0 strongly suggests it would mitigate endothelial dysfunction[13]. In animal models of metabolic syndrome, C15:0 supplementation led to lower plasma markers of endothelial activation and improved insulin-mediated vasodilation, indirectly pointing to better endothelial responsiveness[16].

Furthermore, C15:0’s recently discovered metabolite, pentadecanoylcarnitine, acts on G-protein coupled receptors relevant to vascular tone[65]. Pentadecanoylcarnitine is a full agonist at cannabinoid receptors 1 and 2 (CB1/CB2)[66]. Activation of endothelial CB2 receptors is anti-inflammatory and can promote vasodilation, while CB1 activation in peripheral tissues can cause vasorelaxation (though central CB1 may have opposite effects)[67]. C15:0’s metabolite also antagonizes histamine H1/H2 receptors, which could theoretically blunt histamine-induced endothelial permeability and vasodilation in inflammatory states[68]. These receptor activities of a C15:0-derived molecule underscore the fatty acid’s role in modulating inflammation and vascular signaling in multiple ways[69].

Cardiovascular risk is intimately linked with metabolic health[70]. Insulin resistance, central obesity, dyslipidemia, and hypertension cluster together as the metabolic syndrome, which accelerates atherosclerosis[70]. Intriguingly, higher C15:0 has been associated not only with lower CVD events but also with lower incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) and metabolic syndrome[7], suggesting a role in improving insulin sensitivity and overall metabolic profile. Several lines of evidence support beneficial effects of C15:0 on glucose homeostasis[16].

Prospective cohort studies consistently find that individuals with greater circulating OCSFAs have a substantially reduced risk of developing T2D[16]. In a meta-analysis of eight cohorts, each standard deviation increase in plasma C15:0 was associated with a approximately 14% lower risk of incident T2D[38]. Similarly, C17:0 showed an even stronger inverse association[11]. These relationships persist after adjusting for body adiposity and other dietary factors, implying an intrinsic link between OCFAs and glucose metabolism[11]. In one large study, those in the highest quartile of 15:0 had almost half the risk of T2D compared to those in the lowest quartile[38]. Additionally, higher 15:0 levels have been correlated with lower fasting insulin, lower homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), and better glucose tolerance cross-sectionally. These epidemiological findings align with the idea that OCFAs may enhance insulin sensitivity or reflect diets that promote metabolic health[5].

Controlled experiments lend credibility to a causative role. In vitro studies in skeletal muscle cells have shown that C15:0 directly improves insulin action. One study demonstrated that treating cultured myotubes with C15:0 significantly increased both basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake[71]. This effect was mediated via activation of the AMPK-AS160 pathway, which promotes glucose transporter type 4 (GLUT4) translocation to the cell membrane[72]. Essentially, C15:0 acted as an insulin sensitizer in muscle cells, enhancing their glucose uptake efficiency[16]. It also upregulated genes involved in mitochondrial β-oxidation, indicating improved metabolic flexibility[33]. These cellular results mirror those seen with certain polyunsaturated fatty acids and compounds like metformin that activate AMPK[73].

Animal models reinforce C15:0’s metabolic benefits[53]. In diet-induced obese mice, chronic C15:0 supplementation led to lower fasting glucose and insulin levels relative to controls, suggesting improved whole-body insulin sensitivity[52]. Treated mice had reduced weight gain and adiposity despite equivalent calorie intake, pointing to an increase in energy expenditure or fat oxidation[16]. Indeed, C15:0-fed rodents exhibited upregulation of PPARα target genes in the liver and reduced accumulation of liver fat[53]. Importantly, markers of systemic insulin sensitivity, such as the insulin tolerance test, improved in C15:0-supplemented animals[52]. Another study in a rabbit model of metabolic syndrome found that adding C15:0 mitigated the development of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia over time[74]. These improvements in glycemic control can indirectly benefit the cardiovascular system by reducing the pro-atherogenic influences of hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia.

The link between C15:0 and T2D risk reduction has also been hypothesized to involve gut microbiota[75]. High-fiber diets that foster certain gut microbes produce more propionate, which can raise OCFAs synthesis in the liver[76]. Some have suggested that individuals with fiber-fermenting microbiota profiles might have higher C15:0 and better insulin sensitivity - meaning C15:0 could be a surrogate of a healthy gut environment[57]. However, as noted earlier, direct fiber supplementation did not raise C15:0 in humans, so this connection remains speculative[42]. Nonetheless, it is plausible that a dietary pattern that includes moderate dairy (providing C15:0) alongside fiber is metabolically favorable, and C15:0 is one integrated marker of such a pattern[14].

Clinically, the finding that higher C15:0 is linked to lower new-onset T2D has significant implications[12]. It suggests that consuming foods rich in C15:0, or supplementing it, might help prevent diabetes, thereby also lowering CVD risk given diabetes is a major risk factor. It also raises the provocative notion that some components of dairy fat could be beneficial, contrasting with the traditional view that dairy fat is harmful because of its saturated fat content. Indeed, meta-analyses of observational studies have reported that higher consumption of full-fat dairy is associated with lower incidence of T2D, and C15:0 might be one contributing factor[75].

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a hallmark of both metabolic diseases and cardiac conditions such as HF[77]. Nutrients that support efficient mitochondrial function can have far-reaching benefits for energy metabolism and cell viability[78]. Emerging evidence suggests that C15:0 positively influences mitochondrial bioenergetics, which in turn may impact cardiac muscle performance and resilience[19].

Research by Venn-Watson[13] revealed that C15:0 can “rescue” certain aspects of mitochondrial function under stress. In a series of cell-based assays, C15:0 at physiologically relevant concentrations (around 5-20 μmol/L) was found to restore mitochondrial membrane potential and reduce excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in mitochondria exposed to metabolic stress[16]. Specifically, C15:0 increased the activity of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex II (succinate dehydrogenase), leading to higher production of succinate - a critical substrate in both the tricarboxylic acid cycle and electron transport chain[58]. By enhancing complex II flux, C15:0 helps maintain adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation and prevents buildup of upstream metabolites that can produce ROS. In stressed human cell systems (simulating conditions like oxidative stress and high fat), adding C15:0 led to a significant drop in mitochondrial superoxide levels compared to untreated cells. The optimal concentration for reducing mitochondrial ROS was around 20 μmol/L, at which C15:0 achieved a maximal approximately 30% reduction in ROS output. These findings indicate that C15:0 can act as a mitochondrial antioxidant indirectly, by improving electron transport efficiency and preventing electron leak[79].

The ability of C15:0 to repair mitochondrial function may be related to its incorporation into cell membranes[45]. OCSFAs like C15:0 are relatively resistant to peroxidation and may stabilize mitochondrial membranes[33]. There is a “membrane pacemaker” theory of aging which posits that membranes enriched in peroxidation-resistant fatty acids suffer less oxidative damage over time[80]. By integrating into mitochondrial membranes, C15:0 could reduce lipid peroxidation and preserve the integrity of electron transport complexes[81]. Moreover, C15:0’s activation of AMPK and PPAR pathways promotes mitochondrial biogenesis and turnover, potentially increasing the number of healthy mitochondria in tissues such as cardiac muscle[53].

The heart, with its high energy demands, is particularly sensitive to mitochondrial efficiency[82]. Though direct evidence in humans is pending, several animal studies suggest C15:0 could benefit cardiac function. In diet-induced obese mice, those receiving C15:0 had improved cardiac mitochondrial respiration and higher myocardial ATP levels than controls[13]. Functionally, isolated hearts from C15:0-treated mice demonstrated better contractile recovery after an ischemia-reperfusion challenge, indicating enhanced myocardial resilience[83]. This cardioprotective effect is likely due to reduced oxidative stress and improved metabolic flexibility in the heart[53]. C15:0-fed mice also had lower myocardial fibrosis in high-fat diet models, consistent with less cardiac remodeling under metabolic stress[52].

C15:0’s impact on RBC health also relates to oxygen delivery and cardiac function[13]. Supplementation with C15:0 has been shown to improve RBC stability and reduce hemolysis in vivo. By attenuating anemia (as observed in treated animal models), C15:0 ensures adequate oxygen carrying capacity, which can lighten the load on the heart. Thus, the anti-anemia effect of C15:0 via improving iron metabolism and RBC lifespan - could indirectly preserve cardiac function and reduce HF risk[45].

In HF models, where mitochondrial energy production is insufficient, OCFAs might offer a novel therapeutic angle[16]. Failing hearts often show a shift away from fatty acid oxidation to glucose utilization and a depletion of mitochondrial content[84]. Activating PPARα can encourage the heart to utilize fatty acids more efficiently and potentially reverse some maladaptive metabolic remodeling. While we lack clinical trials in HF patients, it is noteworthy that population studies have linked higher C15:0 with lower incidence of HF hospitalization over long-term follow-up[16]. This raises the hypothesis that lifelong exposure to higher C15:0 (through diet or metabolism) helps maintain myocardial energy balance and prevent the development of cardiomyopathy[46].

Hypertension is a major independent risk factor for CVD, and its pathophysiology involves arterial stiffness, endothelial dysfunction, and neurohormonal dysregulation[85]. While the relationship between fatty acids and blood pressure is complex, there are plausible ways in which C15:0 could influence vascular tone and blood pressure regulation[86].

Epidemiologically, little direct data exists on C15:0 and hypertension incidence or blood pressure levels[5]. However, some cross-sectional studies have noted that individuals with higher OCFA levels tend to have lower blood pressure and lower prevalence of hypertension, though findings are not uniform[19]. In one community-based sample, plasma 15:0 concentrations showed an inverse correlation with systolic blood pressure after adjusting for age and BMI, on the order of a few mmHg difference between top and bottom quartiles[19]. This observation could result from healthier diets or confounding by other factors, but it opens the question of a causal link[7].

Mechanistic evidence points to C15:0’s effects on the endothelium and smooth muscle relaxation[57]. As described, C15:0 reduces endothelial inflammation and likely improves NO bioavailability via AMPK activation[87]. Endothelium-derived NO is a key vasodilator; thus, higher C15:0 could facilitate greater NO-mediated vasodilation and hence lower vascular tone[88]. Additionally, C15:0’s PPARδ activation in vascular smooth muscle might promote a more oxidative, less proliferative phenotype, helping preserve arterial compliance[16].

A novel insight into C15:0’s role in vascular biology comes from its endocannabinoid mimicry. Pentadecanoylcarnitine, an endogenous metabolite of C15:0, acts as a potent agonist at both CB1 and CB2 cannabinoid receptors[66]. The endocannabinoid system is known to modulate blood pressure: Activation of peripheral CB2 receptors generally causes vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects in blood vessels, while CB1 activation can induce transient hypotension by reducing vascular resistance[89]. In experimental models, endocannabinoid agonists can cause blood pressure lowering, and drugs blocking CB1 can raise blood pressure[67]. Therefore, pentadecanoylcarnitine’s CB receptor activation hints that C15:0 might promote vasodilation and lower blood pressure[67]. Moreover, this metabolite’s agonism of serotonin 5-HT1A/1B receptors could influence central sympathetic outflow or local vascular responses, as these receptors are involved in vasomotor control[90]. The metabolite also antagonizes histamine H1/H2 receptors, potentially blunting histamine-induced vasodilation and vascular permeability during inflammatory responses. Collectively, these receptor-mediated activities of C15:0’s derivative suggest a unique role in fine-tuning vascular tone and reactivity[91].

Animal studies provide some support for blood pressure effects[92]. In a rat model prone to hypertension, diets supplemented with OCFAs led to modestly lower blood pressure and less arterial stiffening compared to control high-fat diets which were rich in ECSFAs[93]. Treated rats had improved endothelium-dependent relaxation to acetylcholine, indicating better endothelial function - an important factor in blood pressure regulation. Additionally, chronic C15:0 supplementation in obese rodents attenuated the rise in blood pressure that typically accompanies weight gain, relative to obese animals not receiving C15:0[91]. This suggests a protective effect against the development of hypertension in the context of metabolic syndrome[7].

It should be noted that any blood pressure-lowering influence of C15:0 is likely subtle[92]. Factors like sodium intake, renal function, and overall diet play dominant roles in blood pressure[94]. C15:0 is not expected to have a pharmacologic magnitude of effect akin to antihypertensive medications. However, even a small average reduction 2-4 mmHg in systolic pressure at the population level can have meaningful impacts on CVD outcomes[95]. By improving arterial compliance (through reduced inflammation and better endothelial NO signaling) and possibly affecting central autonomic regulation (through cannabinoid and serotonin pathways), C15:0 could contribute to maintaining normal blood pressure[66].

The gut microbiome has emerged as an important player in cardiometabolic health, influencing everything from inflammation to nutrient harvest and even atherosclerosis via metabolites like trimethylamine N-oxide[96]. In the context of C15:0, the microbiome is relevant both as a source of precursors for OCFAs and as a modulator of host metabolism linked to CVD[97].

As discussed in section 2, rumen bacteria in dairy cows are responsible for producing C15:0 and C17:0 that end up in milk fat[34]. In humans, our gut microbiota can similarly ferment dietary fibers to SCFAs (acetate, propionate, butyrate)[98]. Propionate, in particular, can serve as a substrate for OCFAs synthesis in the liver[33]. A key question has been whether individuals with certain gut microbial compositions (favoring propionate producers like Prevotella or Bacteroidetes) generate more propionate and thus more endogenous C15:0, potentially conferring metabolic benefits. Some cross-sectional studies found that people with higher circulating C15:0 also had higher fiber intake and more SCFA-producing gut microbes, hinting at a microbiome link[99]. One hypothesis is that a high-fiber diet - > more colonic propionate - > more hepatic C15:0 synthesis - > improved metabolic health, which could partly explain why fiber-rich diets are cardioprotective[100].

However, direct evidence suggests that diet-derived propionate might not substantially raise human C15:0 levels except under extreme conditions. The 2021 randomized crossover study by Wu et al[42] gave participants high-fiber vs low-fiber diets and measured plasma OCFAs. Despite large differences in fiber intake (approximately 45 g vs 13 g per day) and presumably colonic SCFA production, circulating C15:0 and C17:0 did not change significantly. This indicates that microbial propionate production is not the rate-limiting step for OCFAs status in humans; direct dietary intake of these fatty acids remains the dominant source[33]. Indeed, when germ-free mice and conventionally raised mice were compared, the presence of gut microbiota did affect hepatic OCFA levels, but diet composition (especially propionate content in feed) was a stronger determinant[43]. One study concluded that bacterial propionate contributes to OCFA formation only when dietary propionate is low, and that high propionate diets can mask microbial contributions[41]. In practical terms, in omnivorous humans consuming various foods, microbiota-driven OCFA synthesis appears to be a minor pathway[33].

Nonetheless, the gut microbiome’s overall influence on host cardiometabolic health could intersect with C15:0 in other ways. OCFAs may reflect a diet that fosters beneficial microbes. Fermented dairy products like yogurt contain probiotics and tend to correlate with metabolic benefits beyond their fat content[101]. It is possible that individuals with higher C15:0 also have a gut microbiome enriched in anti-inflammatory or metabolically favorable bacteria, which together produce a milieu protective against CVD[7]. For instance, certain ruminal bacteria or their analogues in humans might produce unique metabolites or cell wall components that improve lipid and glucose metabolism in the host[99]. These could synergize with C15:0’s direct effects[101].

Conversely, the absence of OCFAs in diets (such as strict vegan diets with no dairy) might coincide with microbial patterns that are not as beneficial[102]. Some researchers have speculated that declining C15:0 levels population-wide (from reduced dairy fat intake) could be an unintended marker of a shift in the microbiome linked with more processed, high-sugar diets replacing dairy[33]. Those diets can encourage dysbiosis and gut-derived inflammation (for example, higher endotoxemia), which can promote atherosclerosis[103]. While speculative, this perspective suggests we consider OCFAs as part of a broader network of diet-gut-heart interactions[104].

The emerging data on C15:0 have stimulated discussion about its potential inclusion in dietary recommendations and therapeutic strategies[105]. Traditionally, saturated fat intake has been counseled to be as low as possible for cardiovascular health[6]. The evidence reviewed here complicates that narrative, indicating that at least one SFA - C15:0 - may be beneficial. This has several translational implications[105].

If C15:0 is indeed cardioprotective, what intake level should individuals target? There is no official dietary reference intake for C15:0, as it has never been historically classified as an essential fatty acid[33]. Conventionally, circulating levels in Western populations consuming dairy tend to cluster around 0.2%-0.4% of total plasma fatty acids[49]. Epidemiologic data indicate that individuals at the higher end of this range - or slightly above - exhibit the lowest risk of disease, as evidenced by studies[7]. For instance, a recent clinical trial demonstrated that an end-of-treatment plasma C15:0 concentration exceeding 5 µg/mL, approximately 0.25%-0.3% of total fatty acids, was associated with measurable health improvements[45]. This concentration may serve as a practical target achievable through dietary means. To attain such levels, one might consume approximately 3-4 servings of full-fat dairy daily, providing an estimated 20-50 mg of C15:0[104]. Notably, observational studies have shown that moderate dairy intake does not correlate with increased CVD risk and, in many instances, is associated with a reduced incidence of stroke and T2D[9] - findings that challenge longstanding concerns about full-fat dairy consumption.

However, these observations reflect conventional dietary intakes, and virtually no research has explored the effects of higher C15:0 levels[33]. Such elevated concentrations, which could exceed the typical 0.2%-0.4% range, would only be pragmatically achievable through supplementation with C15:0, as dietary sources alone are unlikely to suffice[13]. Emerging research efforts are beginning to address this knowledge gap, investigating the potential clinical benefits - such as enhanced cardioprotection - and any associated side effects of these higher levels[79]. For example, preliminary research is examining whether supplemental C15:0 in the 1-2 g/day can safely elevate circulating levels beyond those conventionally observed and how such increases might influence health outcomes[79]. While self-medication with C15:0 is premature pending more definitive trials, these products provide a practical means to elevate C15:0 intake without increasing ECFAs. Safety-wise, doses up to 100-200 mg/day have been well tolerated, with no evidence of raising LDL-C or causing weight gain - in fact, animal toxicology studies suggest a wide safety margin and potential benefits at these doses[45].

From a public health perspective, embracing C15:0’s benefits may involve nuanced dietary guidance[7]. Rather than blanket advice to minimize all saturated fat, guidelines could encourage inclusion of certain whole foods that provide C15:0 and have net favorable nutrient profiles[15]. This aligns with modern nutrition science shifting focus from single nutrients to whole foods and dietary patterns[106]. For instance, fermented dairy products are associated with lower CVD risk despite containing saturated fat, and C15:0 may be one factor behind this paradox[107]. Research priorities include conducting intervention studies where increasing C15:0 intake through diet or supplements, is the primary manipulation, and then observing effects on surrogate endpoints like LDL particle number, inflammatory markers, glucose tolerance, blood pressure, and possibly arterial function[45]. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) in humans designed to test causality would be especially informative - for example, giving a C15:0 supplement vs placebo to individuals with metabolic syndrome for 6-12 months to see if CVD risk factors improve[53].

Another priority is exploring C15:0 in patient populations such as those with HF or diabetes[7]. Given its multifaceted mechanisms, C15:0 might serve as an adjunct therapy to improve outcomes or reduce medication requirements[13]. For instance, could adding C15:0 help glycemic control in diabetes or improve exercise tolerance in HF by enhancing mitochondrial function? These questions merit investigation. Additionally, it will be important to determine if there are any long-term adverse effects of elevated C15:0 intake. So far, observational studies have not flagged any harms - if anything, higher C15:0 associates with lower risk of diseases like cancer and dementia as well[108]. Toxicology assessments in animals have not found evidence of organ damage or pro-arrhythmic potential with C15:0[109].

Research on C15:0 has surged in the past decade, but several important knowledge gaps remain[33]. First, causality needs to be established. To date, the evidence linking C15:0 to lower CVD and T2D risk is largely observational[7]. Randomized trials in humans are needed to determine if increasing C15:0 intake directly leads to improved clinical outcomes or surrogate endpoints[7]. A priority is a long-term RCT assessing whether C15:0 supplementation can favorably alter lipids, inflammation, glycemic control, or blood pressure in at-risk individuals. Such a trial would also clarify optimal dosing and safety over an extended period[45].

Second, the mechanistic understanding, while advanced, is not complete. Further studies should dissect how C15:0 interacts with cellular pathways in different tissues. For example, how exactly does C15:0 incorporation into cell membranes affect membrane proteins and receptors[33]? Does C15:0 influence gut hormone secretion (such as glucagon-like peptide-1) or adipokine release, which could link to metabolic effects? The discovery of pentadecanoylcarnitine’s receptor targets raises new questions about neural and immune pathways that C15:0 might modulate[81]. Future work employing metabolomics and receptor assays could uncover additional bioactive metabolites of C15:0 and their roles[110].

Another gap lies in population diversity. Most epidemiologic studies on C15:0 have been in European or American cohorts with significant dairy consumption[33]. It is unclear if the inverse associations hold in populations with low-dairy diets. Studying groups with minimal C15:0 exposure could illuminate whether extremely low levels confer higher risk. Additionally, genetic studies might identify metabolic pathways that govern C15:0 status and interact with diet, providing insight into inter-individual variability[111].

The interplay between C15:0 and other dietary components warrants investigation. Does the matrix of dairy (calcium, protein, vitamin D) amplify or attenuate C15:0’s effects[33]? Would adding C15:0 to a low-fat diet reproduce the benefits seen with dairy-inclusive diets? Also, understanding the time-course is important: How quickly do beneficial changes manifest after raising C15:0 intake, and how long are they sustained[112]? These questions could be addressed in controlled feeding studies of varying durations.

Finally, the broader implications for dietary guidelines need careful consideration[106]. If evidence solidifies that C15:0 is cardioprotective, nutrition policy may need to shift from blanket SFA limits to a more nuanced approach distinguishing fatty acid subtypes[7]. This would involve educating both clinicians and the public that certain foods high in specific SFAs (like dairy fat containing C15:0) can be part of a heart-healthy diet[113]. Ongoing and future cohort studies will be instrumental in corroborating that message across different cultural diets and baseline risk profiles[7].

C15:0 has emerged as a structurally distinctive SFA with an expanding evidence base for cardioprotection. A recent pooled analysis of three large prospective cohorts reported an approximately 12% hazard reduction for incident CVD per standarddeviation increase in circulating C15:0, independent of traditional risk factors[5]. Given that CVD remains the leading global cause of mortality, according to the 2025 American Heart Association update[23], nutrients capable of closing the prevention gap warrant close scrutiny. Intervention data now suggest causality. A 12-week, double-blind randomized trial showed that 200 mg/day of purified C15:0 safely elevated plasma levels and tended to lower non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides without raising LDL-C[45]. These neutral-to-favorable lipid changes mirror workshop conclusions that the cardiometabolic impact of dairy fat depends more on fattyacid subtype than total saturated-fat content[105].

Mechanistic findings provide biological plausibility. C15:0 is an agonist of PPARα/δ and AMPK, pathways that enhance β-oxidation, bolster mitochondrial respiration and suppress reactive-oxygen-species generation. In cardio

Gut-liver interactions add an additional axis of benefit: Parabacteroides distasonis converts dietary inulin to C15:0, thereby suppressing dietinduced steatohepatitis and systemic inflammation[52]. Cell-membrane incorporation studies indicate that C15:0 stabilizes mitochondrial dynamics and maintains ATP output under metabolic stress[33]. Conversely, AMPK-deficiency models illustrate that loss of this signaling axis impairs fatty-acid oxidation and vascular repair, underscoring the relevance of C15:0-PPAR/AMPK crosstalk[114].

Despite these advances, several uncertainties remain. First, all population studies are observational, leaving residual confounding a possibility. Second, optimal dosing is undefined; the randomized trial achieved plasma concentrations typical of the upper quintile of habitual dairy consumers, but higher supplementlevel intakes have yet to be tested over longer periods. Third, the relative contribution of endogenous (microbial-propionate-derived) vs exogenous C15:0 to cardiometabolic benefit is unresolved, as increases in colonic propionate do not consistently translate into higher OCSFA pools in humans[5].

These gaps inform research priorities: (1) Adequately powered, multi-center trials testing ≥ 1 g/day C15:0 against LDL-particle number, vascular inflammation and glycemic control; (2) Mendelian-randomization studies leveraging genetic determinants of OCSFA metabolism; and (3) Exploration of microbiome engineering to enhance endogenous production. From a dietary-guideline perspective, current evidence challenges blanket recommendations to replace regularfat dairy with low-fat alternatives. Comprehensive reviews indicate that milk, yogurt and cheese are neutrally associated with CVD risk irrespective of fat content[105], implying that retaining natural C15:0 within whole-food matrices may be advantageous.

Moderate consumption of grass-fed dairy, supplying approximately 20-50 mg C15:0/day, appears metabolically neutral and potentially beneficial, with safety confirmed up to 200 mg/day in humans[45]. Converging epidemiological, interventional and mechanistic data position C15:0 as a promising bioactive lipid capable of addressing persistent gaps in CVD prevention. Deliberate differentiation between odd- and even-chain saturated fats in both research and policy frameworks is warranted; the forthcoming decade of well-designed trials will determine whether C15:0 transitions from biomarker to therapeutic nutrient.

This narrative review has inherent limitations that must be acknowledged when interpreting its conclusions. First, as a narrative non-systematic review, the selection of literature may be subjective and prone to bias. The paper prioritized recent and high-impact studies to illustrate key points, but we may have overlooked some relevant publications. Unlike a formal systematic review, we did not comprehensively search all databases or formally assess study quality using predefined criteria. Thus, there is a risk of emphasis on findings that support the review’s premise while underrepresenting null or conflicting results. To mitigate this, we did attempt to cite meta-analyses and representative cohort studies rather than isolated positive findings.

Second, much of the evidence connecting C15:0 to CVD outcomes comes from observational studies[7]. These can suffer from residual confounding and cannot prove causation[14]. Individuals with high C15:0 levels might differ in many ways such as diet, lifestyle, socioeconomic status from those with low levels[5]. Although multivariate adjustments were made in cited studies, unknown confounders could still influence the results[15]. Third, the translational implications remain speculative at this stage. No large clinical trial has tested C15:0 supplementation for CVD prevention or any hard outcome. Therefore, any recommendations about intake targets or supplement use are based on surrogate endpoints and inference. There may be unrecognized harms of isolated C15:0 intake or thresholds beyond which additional C15:0 provides no benefit. Long-term safety data in humans are lacking. For instance, while short-term studies showed no LDL-C increase, it is possible that chronic high-dose C15:0 could have unforeseen metabolic or signaling effects[45].

Additionally, many mechanistic insights come from animal or cell studies, which do not always translate neatly to human physiology. Doses of C15:0 used in rodents may not be equivalent to typical human intakes. Rodent models of CVD and diabetes have differences. Thus, caution is needed in extrapolating mechanistic data to clinical relevance. Finally, publication bias might be at play in this emerging field - positive results on C15:0 may be more likely published and disseminated, whereas studies that found no association might be less visible. As with any new paradigm challenging conventional wisdom, there is a need for balanced scrutiny. We have tried to present both supportive and cautionary perspectives, but our review could inadvertently paint an overly optimistic picture of C15:0. In light of these limitations, the conclusions of this review should be viewed as hypothesis-generating. Further rigorous research is required to validate the propositions made herein and to guide evidence-based recommendations regarding penta

In summary, accumulating evidence supports a context-specific role for OCFA C15:0 in cardiometabolic health. This review distils three overarching insights that advance the field: (1) Population-based cohorts consistently link higher C15:0 exposure with lower cardiovascular risk; (2) Mechanistic studies converge on complementary lipid-lowering, antiinflammatory, and mitochondrialsupportive actions; and (3) Early-phase supplementation trials demonstrate biological plausibility and real-world translational potential. By crystallizing these insights, the present synthesis reframes C15:0 as a candidate cardioprotective nutrient and sets a research agenda for precision-fatty-acid nutrition. C15:0 has emerged as a fascinating example of a nutrient that defies the traditional categorization of saturated fats as universally harmful. This OCFA - obtained mainly through dairy fat - is consistently associated with favorable cardiometabolic outcomes in population studies. Individuals with higher circulating C15:0 tend to experience lower rates of CVD, T2D, and perhaps other chronic diseases. The totality of evidence reviewed suggests that C15:0 is not merely a passive marker of dairy intake, but an active fatty acid with multi-system benefits.

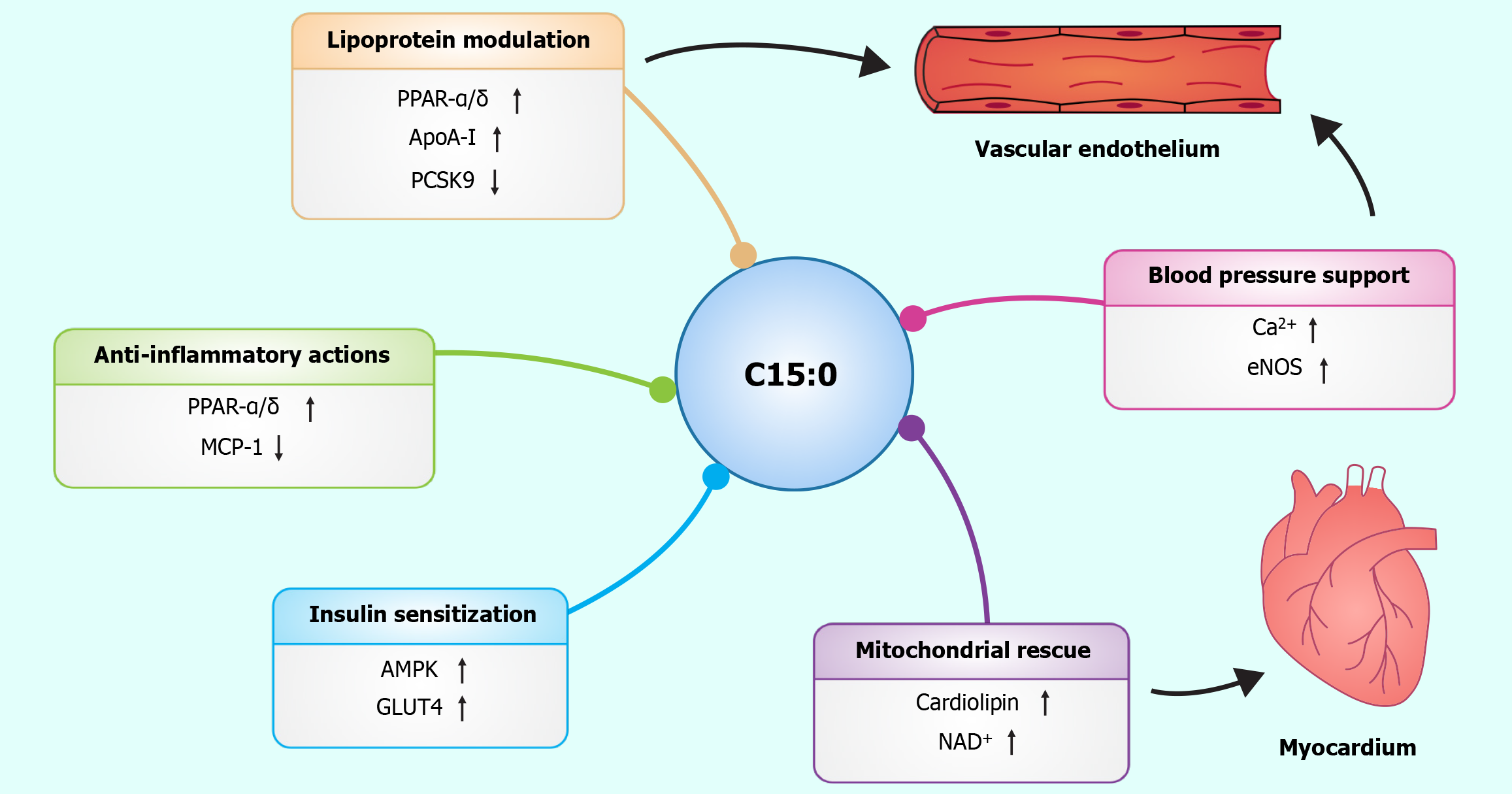

Mechanistically, C15:0 favorably influences several pathways integral to CVD development. It produces a more atheroprotective lipid profile suppresses inflammation and oxidative stress, enhances insulin sensitivity, and supports mitochondrial function and energy homeostasis. These effects converge to reduce endothelial dysfunction, slow atherogenesis, and improve metabolic health - all of which contribute to cardiovascular risk reduction (Figure 4). Importantly, C15:0 accomplishes this without the adverse effects typically attributed to SFAs, highlighting that context and molecular structure matter in nutrition.

From a clinical and public health perspective, these insights beckon a re-examination of dietary guidance. Foods rich in C15:0, like certain dairy products, may confer benefits that outweigh their SFA content. It would be premature to recommend C15:0 supplementation for all, but these findings open the door to personalized nutrition strategies. Those with low C15:0 levels, for instance, individuals avoiding all grass fed dairy, might eventually be identified as at-risk for a “C15:0 deficiency” state, analogous to insufficient omega-3 status, though this concept requires validation.

Pentadecanoic acid (C15:0) represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of saturated fatty acids and cardiovascular health. This odd-chain saturated fatty acid, obtained primarily through grass-fed dairy consumption, demonstrates consistent inverse associations with cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes in prospective cohort studies. The biological mechanisms underlying these associations—including favorable lipoprotein modulation, anti-inflammatory effects, enhanced insulin sensitivity, and mitochondrial support—provide a compelling mechanistic rationale for the observed epidemiological findings.

The accumulated evidence challenges the traditional view that all saturated fats uniformly increase cardiovascular risk. C15:0 illustrates that molecular structure and metabolic fate, rather than simple saturation status, determine the health effects of dietary fatty acids. This distinction has important implications for dietary guidance, suggesting that moderate consumption of C15:0-rich foods like grass-fed dairy products may contribute to, rather than detract from, cardiovascular health.

Future research priorities include adequately powered randomized controlled trials testing C15:0 supplementation on clinical endpoints, Mendelian randomization studies to strengthen causal inference, and investigations into optimal dosing strategies. As our understanding evolves, C15:0 may transition from a biomarker of dairy intake to a therapeutic nutrient with defined intake recommendations. In the meantime, a diet that includes natural sources of odd-chain fatty acids, particularly from high-quality dairy products, may represent one component of a heart-healthy lifestyle that deserves reconsideration in light of this emerging evidence.

| 1. | Martin SS, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Barone Gibbs B, Beaton AZ, Boehme AK, Commodore-Mensah Y, Currie ME, Elkind MSV, Evenson KR, Generoso G, Heard DG, Hiremath S, Johansen MC, Kalani R, Kazi DS, Ko D, Liu J, Magnani JW, Michos ED, Mussolino ME, Navaneethan SD, Parikh NI, Perman SM, Poudel R, Rezk-Hanna M, Roth GA, Shah NS, St-Onge MP, Thacker EL, Tsao CW, Urbut SM, Van Spall HGC, Voeks JH, Wang NY, Wong ND, Wong SS, Yaffe K, Palaniappan LP; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. 2024 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2024;149:e347-e913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1087] [Cited by in RCA: 1572] [Article Influence: 786.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 2. | Aggarwal R, Yeh RW, Joynt Maddox KE, Wadhera RK. Cardiovascular Risk Factor Prevalence, Treatment, and Control in US Adults Aged 20 to 44 Years, 2009 to March 2020. JAMA. 2023;329:899-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 58.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Venier D, Capocasa M. Macronutrients and cardiovascular diseases: A narrative review of recent scientific literature. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2025;68:32-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mazur M, Przytuła A, Szymańska M, Popiołek-Kalisz J. Dietary strategies for cardiovascular disease risk factors prevention. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2024;49:102746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Retterstøl K, Rosqvist F. Fat and fatty acids - a scoping review for Nordic Nutrition Recommendations 2023. Food Nutr Res. 2024;68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Griffin BA, Lovegrove JA. Saturated fat and CVD: importance of inter-individual variation in the response of serum low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Proc Nutr Soc. 2025;84:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shi F, Chowdhury R, Sofianopoulou E, Koulman A, Sun L, Steur M, Aleksandrova K, Dahm CC, Schulze MB, van der Schouw YT, Agnoli C, Amiano P, Boer JMA, Bork CS, Cabrera-Castro N, Eichelmann F, Elbaz A, Farràs M, Heath AK, Kaaks R, Katzke V, Keski-Rahkonen P, Masala G, Moreno-Iribas C, Panico S, Papier K, Petrova D, Quirós JR, Ricceri F, Severi G, Tjønneland A, Tong TYN, Tumino R, Wareham NJ, Weiderpass E, Di Angelantonio E, Forouhi NG, Danesh J, Butterworth AS, Kaptoge S. Association of circulating fatty acids with cardiovascular disease risk: analysis of individual-level data in three large prospective cohorts and updated meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025;32:233-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Puttappa N, Kumar RS, Kuppusamy G, Radhakrishnan A. Nano-facilitated drug delivery strategies in the treatment of plasmodium infection. Acta Trop. 2019;195:103-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao B, Gan L, Graubard BI, Männistö S, Fang F, Weinstein SJ, Liao LM, Sinha R, Chen X, Albanes D, Huang J. Plant and Animal Fat Intake and Overall and Cardiovascular Disease Mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2024;184:1234-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liang J, Zhou Q, Kwame Amakye W, Su Y, Zhang Z. Biomarkers of dairy fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta analysis of prospective studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:1122-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li Z, Lei H, Jiang H, Fan Y, Shi J, Li C, Chen F, Mi B, Ma M, Lin J, Ma L. Saturated fatty acid biomarkers and risk of cardiometabolic diseases: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Front Nutr. 2022;9:963471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang S, Hu C, Lin H, Jia X, Hu R, Zheng R, Li M, Xu Y, Xu M, Zheng J, Zhao X, Li Y, Chen L, Zeng T, Ye Z, Shi L, Su Q, Chen Y, Yu X, Yan L, Wang T, Zhao Z, Qin G, Wan Q, Chen G, Dai M, Zhang D, Qiu B, Zhu X, Liu R, Wang X, Tang X, Gao Z, Shen F, Gu X, Luo Z, Qin Y, Chen L, Hou X, Huo Y, Li Q, Wang G, Zhang Y, Liu C, Wang Y, Wu S, Yang T, Deng H, Zhao J, Mu Y, Xu G, Lai S, Li D, Ning G, Wang W, Bi Y, Lu J; 4C Study Group. Association of circulating long-chain free fatty acids and incident diabetes risk among normoglycemic Chinese adults: a prospective nested case-control study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2024;120:336-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Venn-Watson S. The Cellular Stability Hypothesis: Evidence of Ferroptosis and Accelerated Aging-Associated Diseases as Newly Identified Nutritional Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0) Deficiency Syndrome. Metabolites. 2024;14:355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kiesswetter E, Neuenschwander M, Stadelmaier J, Szczerba E, Hofacker L, Sedlmaier K, Kussmann M, Roeger C, Hauner H, Schlesinger S, Schwingshackl L. Substitution of Dairy Products and Risk of Death and Cardiometabolic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Curr Dev Nutr. 2024;8:102159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jayedi A, Soltani S, Emadi A, Ghods K, Shab-Bidar S. Dietary intake, biomarkers and supplementation of fatty acids and risk of coronary events: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64:12363-12382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Venn-Watson S, Schork NJ. Pentadecanoic Acid (C15:0), an Essential Fatty Acid, Shares Clinically Relevant Cell-Based Activities with Leading Longevity-Enhancing Compounds. Nutrients. 2023;15:4607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Techeira N, Keel K, Garay A, Harte F, Mendoza A, Cartaya A, Fariña S, López-Pedemonte T. Milk fatty acid profile from grass feeding strategies on 2 Holstein genotypes: Implications for health and technological properties. JDS Commun. 2023;4:169-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wu S, Luo H, Zhong J, Su M, Lai X, Zhang Z, Zhou Q. Differential Associations of Erythrocyte Membrane Saturated Fatty Acids with Glycemic and Lipid Metabolic Markers in a Chinese Population: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients. 2024;16:1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Huang L, Li S, Zhou Q, Ruan X, Wu Y, Wei Q, Xie H, Zhang Z. Associations of erythrocyte membrane fatty acids with blood pressure in children. Clin Nutr. 2025;46:30-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou X, Sun X, Zhao H, Xie F, Li B, Zhang J. Biomarker identification and risk assessment of cardiovascular disease based on untargeted metabolomics and machine learning. Sci Rep. 2024;14:25755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Shahjehan RD, Sharma S, Bhutta BS. Coronary Artery Disease. 2024 Oct 9. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Mensah GA, Fuster V, Murray CJL, Roth GA; Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaborators. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks, 1990-2022. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:2350-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 888] [Article Influence: 296.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Martin SS, Aday AW, Allen NB, Almarzooq ZI, Anderson CAM, Arora P, Avery CL, Baker-Smith CM, Bansal N, Beaton AZ, Commodore-Mensah Y, Currie ME, Elkind MSV, Fan W, Generoso G, Gibbs BB, Heard DG, Hiremath S, Johansen MC, Kazi DS, Ko D, Leppert MH, Magnani JW, Michos ED, Mussolino ME, Parikh NI, Perman SM, Rezk-Hanna M, Roth GA, Shah NS, Springer MV, St-Onge MP, Thacker EL, Urbut SM, Van Spall HGC, Voeks JH, Whelton SP, Wong ND, Wong SS, Yaffe K, Palaniappan LP; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Committee. 2025 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics: A Report of US and Global Data From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2025;151:e41-e660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 405.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Van Dyke M, Greer S, Odom E, Schieb L, Vaughan A, Kramer M, Casper M. Heart Disease Death Rates Among Blacks and Whites Aged ≥35 Years - United States, 1968-2015. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Stieglis R, Verkaik BJ, Tan HL, Koster RW, van Schuppen H, van der Werf C. Association Between Delay to First Shock and Successful First-Shock Ventricular Fibrillation Termination in Patients With Witnessed Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest. Circulation. 2025;151:235-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Joseph P, Lanas F, Roth G, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Lonn E, Miller V, Mente A, Leong D, Schwalm JD, Yusuf S. Cardiovascular disease in the Americas: the epidemiology of cardiovascular disease and its risk factors. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2025;42:100960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hardy ST, Jaeger BC, Foti K, Ghazi L, Wozniak G, Muntner P. Trends in Blood Pressure Control among US Adults With Hypertension, 2013-2014 to 2021-2023. Am J Hypertens. 2025;38:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 39.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Woodruff RC, Tong X, Loustalot FV, Khan SS, Shah NS, Jackson SL, Vaughan AS. Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Trends, 2010-2022: An Update with Final Data. Am J Prev Med. 2025;68:391-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Woodruff RC, Tong X, Khan SS, Shah NS, Jackson SL, Loustalot F, Vaughan AS. Trends in Cardiovascular Disease Mortality Rates and Excess Deaths, 2010-2022. Am J Prev Med. 2024;66:582-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 65.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tsampasian V, Bäck M, Bernardi M, Cavarretta E, Dębski M, Gati S, Hansen D, Kränkel N, Koskinas KC, Niebauer J, Spadafora L, Frias Vargas M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Vassiliou VS. Cardiovascular disease as part of Long COVID: a systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2025;32:485-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Papajorgji-Taylor D, Sheppler CR, McMullen C, O'Connor PJ, Gold R. Virtual care is a double-edged sword: Adjusting preventive care service delivery in community health clinics during COVID-19. J Family Med Prim Care. 2024;13:3792-3797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2024;403:2133-2161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2282] [Cited by in RCA: 2742] [Article Influence: 1371.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ciesielski V, Legrand P, Blat S, Rioux V. New insights on pentadecanoic acid with special focus on its controversial essentiality: A mini-review. Biochimie. 2024;227:123-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |