INTRODUCTION

Blood coagulation is a highly regulated physiological process essential for maintaining vascular integrity and preventing excessive blood loss following injury[1]. The aggregation of platelets at sites of vascular injury plays a central role in blood coagulation, initiating the release of coagulation factors that lead to fibrin clot formation[2]. In the circulating blood, the presence of anticoagulation factors and inhibitors of platelet activation and aggregation prevents the formation of a blood clot inside a blood vessel, known as thrombosis, obstructing the blood flow[2]. Notably, bleeding disorders such as thrombocytopenia, Glanzmann thrombasthenia, and Bernard-Soulier syndrome are associated with defective mechanisms of platelet aggregation, whereas hemophilia and von Willebrand disease arise from genetic mutations or dysfunctions in clotting factors. These conditions often lead to internal or external haemorrhage for which the options for complete cure remain limited[3,4]. Neurotransmitters, primarily known for their roles in neuronal communication, are increasingly recognized to influence platelet production and function. Emerging evidence suggests that acetylcholine (ACh), a major neurotransmitter, also functions as an endogenous inhibitor of platelet activation, as evidenced by the presence of cholinergic receptors, particularly muscarinic and nicotinic subtypes, on the surface of circulating platelets[5–7]. Notably, excessive levels of ACh or exposure to its agonists have been associated with platelet inactivation, resulting in bleeding disorders[6–8]. However, the functional relationship between abnormal neurotransmitter levels and clotting disorders remains largely unexplored and represents a novel aspect of future investigation. In general, abnormal aging, neurocognitive disorders and neuromuscular diseases have been linked to altered levels of ACh and its downstream signaling[9,10]. While cholinergic hypofunction is responsible for neurodegeneration and dementia accompanied by enhanced thrombus formation, over-production of ACh, leading to the cholinergic crisis could represent a potential risk factor for internal haemorrhage and delayed external blood clotting[6,10]. Considering the facts, altered levels of ACh may be an underlying cause of delayed or impaired blood clotting process in aging and various diseases. Notably, aging is associated with multiple alterations in the coagulation system, often resulting in the seemingly adverse condition of heightened risks for both thrombosis and bleeding[11]. The abnormal levels of ACh are recognized as one of the most prominent physiological changes associated with aging and various diseases. Therefore, pharmacological agents that target synthesis, release or the downstream pathways of ACh could be a potential therapeutic strategy for restoring platelet count and supporting coagulation, thereby preventing internal or external bleeding under unforeseen circumstances. Recent studies suggest that certain drugs used to treat movement and neurocognitive disorders, primarily through the modulation of ACh levels and its associated enzymes, are also likely to influence circulating platelet counts[8,12]. However, studies on the platelet-modulating effects of such neurotransmitter-targeting agents and their impact on blood coagulation remains obscure.

Botulinum toxin (BoNT) is a potent neuromodulator that effectively blocks the release of ACh-containing synaptic vesicles at the neuromuscular junctions[13]. While excessive levels of ACh are identified as an underlying determinant of neuromuscular diseases, therapeutic forms of BoNT provide considerable medical relief from abnormal muscle stiffness in neuromuscular diseases and movement disorders[13]. Beyond its neuromuscular applications, the therapeutic benefits of BoNT have been increasingly recognized against various pathogenic conditions, including headache, hyperhidrosis, overactive bladder diseases, eyelid problems, anxiety, and memory loss[13,14]. Besides, BoNT is widely used in various aesthetic facial reconstructive procedures[14,15]. Recent reports revealed that intramuscular injection of BoNT enhances the number of circulating platelets in individuals undergoing cosmetic management[16]. Eventually, the BoNT-mediated increase in platelet count has also been reported in the blood samples of aging experimental mice[17]. Given the established role of ACh in suppressing platelet function and the ability of BoNT to inhibit ACh release, BoNT treatment could potentially enhance platelet activation and aggregation, thereby aiding in defences against haemorrhagic episodes. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of BoNT treatment on experimental bleeding episodes, blood loss, clotting time, and the extent of platelet activation and aggregation involved in coagulation events in aging mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Treatment of BoNT in experimental animals

Male BALB/c mice aged 7-8 months (n = 12) were assigned randomly into two groups, namely the control group (n = 6) and the BoNT group (n = 6). BoNT (50U; BOTOX®, Allergan, Dublin, Ireland) was reconstituted in 5 mL of 0.9% sterile saline as stock. Further, it was diluted around 83-fold with the required volume of sterile saline as a working solution. Mice of around 30 grams in the BoNT group received a single intramuscular injection of BoNT (0.03 U in 250 μL, corresponding to 1 U per kilogram (Kg) of bodyweight (BW), while control mice were administered an equivalent volume of sterile saline as previously described[17]. The injection was delivered into the vastus lateralis muscle of the thigh. After 30 days, animals were subjected to a tail bleeding assay followed by assessments of clotting time, platelet activation, and prothrombin time in the blood samples as per the prescribed and standard protocols[18]. The experimental mice were maintained (20–22 °C) in the animal house facility, Bharathidasan University at a 12-hour light/dark cycle with free access to feed and water as per the standard procedures. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the approval of the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee, under the regulation of the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals, India (Ref No: BDU/IAEC/P27/2018).

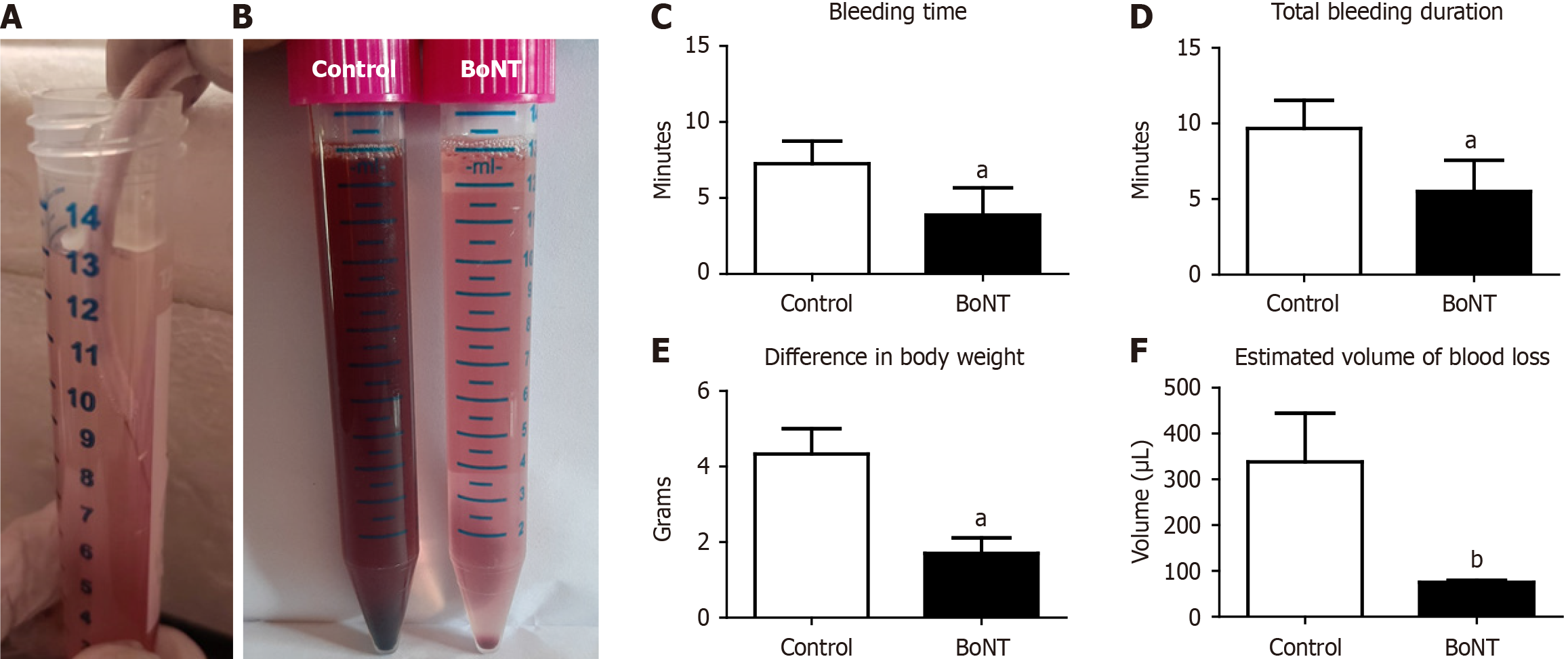

Tail bleeding assay, assessment of blood loss and clotting time in experimental mice

To investigate the effect of BoNT on the duration of bleeding and volume of blood loss, experimental mice were subjected to a standard tail bleeding assay. The tail bleeding assay is a widely used in vivo experimental method to evaluate hemostasis and degree of coagulation, reflecting the function of platelets and the cascade of events involved in blood clotting in small laboratory animals. Following an anaesthetic procedure as described by Yesudhas et al[17], each mouse was placed on a stage and the tail tip was vertically positioned about 2 cm below the body horizon. A distal 10 mm segment of the tail was amputated with sterile scissors. The tail was immediately immersed in a 15-mL falcon tube containing isotonic 0.9% saline, pre-warmed at 37 °C in a water bath (Kemi, India). The duration of bleeding was recorded using a digital stopwatch and each animal was monitored for 30 minutes to examine re-bleeding events. BW was recorded before and after the tail bleeding assay, and the loss of blood volume was estimated using the following formulas as previously described[19].

Volume of blood loss = (initial body weight before tail bleeding - body weight after tail bleeding) × (average blood volume per Kg BW).

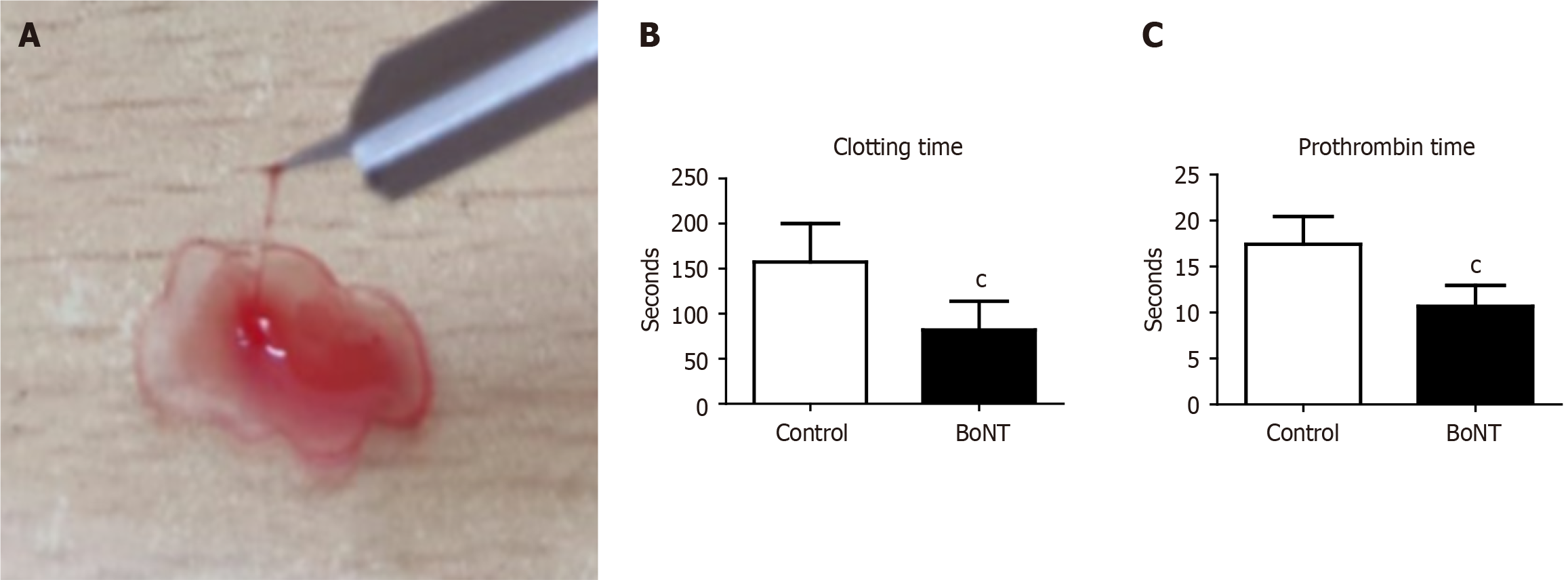

Further, a drop of blood from each animal was placed on a clean microscopic glass slide and the blood was pulled periodically in an upward direction using a lancet needle every 30 seconds. The time taken for the formation of the fibrin threads in the blood sample on the glass slide was estimated as the clotting time.

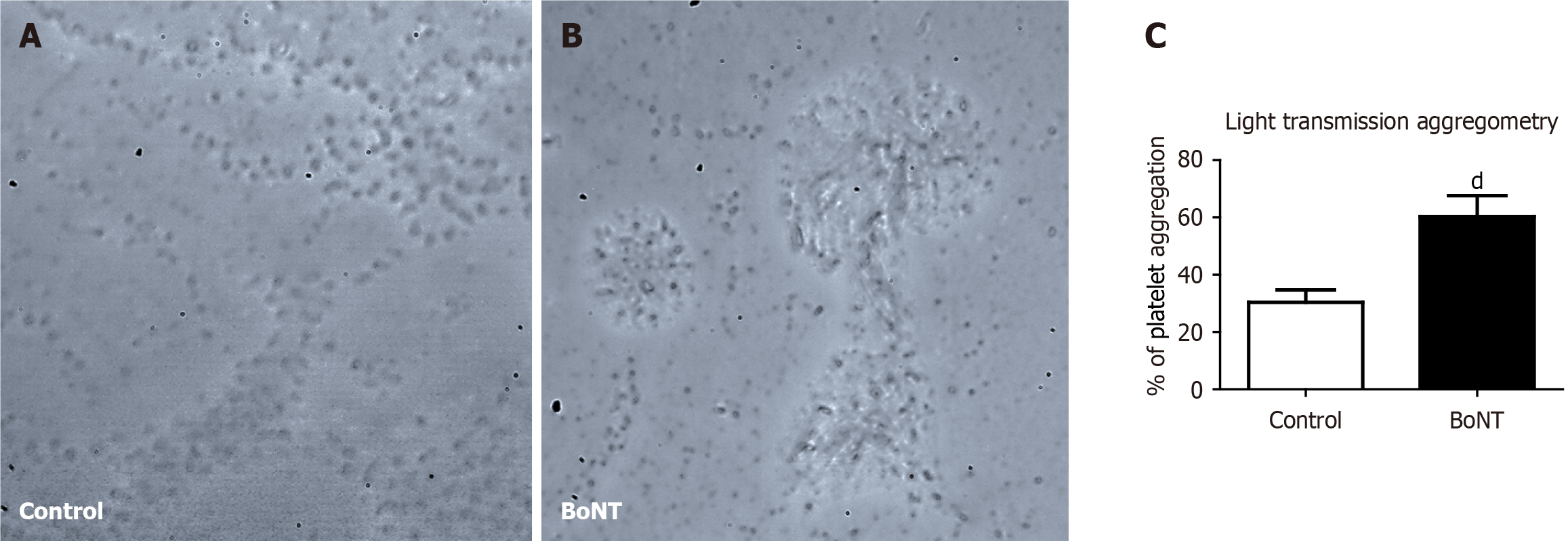

Estimation of prothrombin time and degree of platelet aggregation in the blood samples

Prothrombin time is a widely used experimental measure to evaluate the extrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade. It estimates the time required for plasma to clot upon the addition of thromboplastin and calcium. Prothrombin time reflects the functional activity of fibrinogen, prothrombin and the key conversion of coagulation factors VII and X. To investigate the effect of BoNT on the prothrombin time, around 250 μL of blood was collected from each anesthetized mouse by cardiac puncture. The blood was equally distributed in two sterile containers with 3.2% trisodium citrate buffer (Tulip diagnostics, India) in a 9:1 ratio. One set of blood samples was centrifuged (C-24 Plus, REMI, India) at 2500 g for 15 minutes at room temperature. Further, 100 μL of plasma was separated in a new sterile tube in which 200 μL of prewarmed Uniplastin® sensitive thromboplastin reagent (Tulip Diagnostics, India) was added. The reaction mixture was incubated in a water bath at 37 °C and the time taken for the formation of a visible solid gel clot was recorded using a digital stopwatch to determine the prothrombin time. The other set of blood samples was processed for platelet aggregation analysis. Blood was initially centrifuged at 180 g for 10 minutes to separate plasma containing platelets. The supernatant containing platelets was transferred to a fresh sterile tube and centrifuged again at 1550 g for 10 minutes. As the platelets are sedimented at the bottom of the tube, the upper 2/3rd portion containing platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was carefully removed and added to a separate tube. The platelet pellets were resuspended in the remaining 1/3rd lower portion of plasma by gently shaking the tube and considered platelet-rich plasma (PRP). These samples were used for the light transmission aggregometry (LTA) to measure the platelet aggregation as described previously[20]. A 96-well microtiter plate was incubated with 20 μL of phosphate-buffered saline (HiMedia, India) in which 25 μL of PRP sample and 5 μL of 2.5 μM adenosine diphosphate (SRL, India) were added. In parallel, a similar reaction was performed using 25 μL of PPP counterpart. The final assay volume of 50 μL in the microplate was thoroughly mixed and incubated for 10 minutes[21,22]. Absorbance was measured at 595 nm using a microplate reader. The degree of platelet aggregation was calculated from the optical density (OD) after adding agonists in PRP at a given time using the following formula:

The percentage of platelet aggregation (%) = [(OD of PRP with agonist) - (OD of PRP)]/[(OD of PPP) - (OD of PRP)] × 100.

Statistical analysis

The data values have been represented as mean ± SD. A student’s t-test was applied to measure the statistical significance. All the statistical analyses were made using GraphPad Prism. The significance level was assumed at P < 0.05 unless otherwise indicated.

DISCUSSION

The purified form of BoNT has increasingly been recognized as a therapeutic agent to manage movement deficits in various disorders that include dystonia, ataxia, Huntington’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease[13]. Many neurological and cognitive disorders have been associated with peripheral immunological mechanisms and alterations in circulating platelet levels[21]. Given that BoNT treatment is known to modulate immune responses in the blood, its platelet-enhancing effects have become increasingly evident, suggesting a potential role in regulating blood coagulation parameters[17]. Although the neuromodulator effects of BoNT have been extensively studied, its role on the regulation of blood coagulation remains unexplored. In this study, we demonstrated that BoNT injection in experimental aging mice improved blood coagulation events, as evidenced by reduced blood volume loss, shortened clotting time, decreased prothrombin time, and enhanced platelet aggregation. The present findings provide experimental validation and interpretation of previous observations on BoNT treatment on bleeding-related outcomes.

Notably, existing reports indirectly indicated that intramuscular injection of therapeutic BoNT reduces the risk of bleeding incidents in subjects with different pathological complications[22,23]. BoNT therapy in patients who had been receiving long-term administration of anticoagulants such as warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, appeared to reduce the risk of bleeding complications[24]. Further, Yoshida[25] reported that injection of therapeutic BoNT in oromandibular dystonia patients lowered the risk of arterial bleeding. Moreover, therapeutic BoNTs have been recommended as a potent management therapy for spasticity among patients with hemophilia[26]. Despite these findings, experimental evidence directly demonstrating the effect of BoNT treatment on the regulation of blood coagulation is limited. Therefore, the outcomes of this study provide a strong foundation to support previous observations that BoNT treatment facilitates blood coagulation events.

It is well established that elevated levels of ACh inhibit platelet activation and coagulation, potentially impairing clot formation. Abnormal levels of ACh have been reported to interfere with the release of key clotting factors from the kidney into the bloodstream[27]. Besides, BoNT treatment might also be directly associated with the transcriptional upregulation of clotting factors and compensate for the functions of cofactors that are important for the blood coagulation cascades, regardless of ACh. For example, serotonin has been reported to play a crucial role in promoting platelet aggregation and vasoconstriction of surrounding blood vessels[28], while antidepressant and anxiolytic effects of therapeutic BoNT injection have been reported to act via the induced level of serotonin[29]. Besides, collagen has been identified as the viable thrombogenic component of the sub-endothelium, and following vascular damage, circulating platelets appear to be activated and adhere upon exposure to collagen[30]. Furthermore, BoNT has been reported to promote the production of collagen, its pro-coagulation characteristics might involve platelet activation and adhesion[30]. Moreover, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a key factor responsible for neuroplasticity, is known to be reduced in many neurological disorders[31]. Under physiological conditions, BDNF has been reported to facilitate platelet aggregation through small GTPase Rac1-mediated pathways[32]. Therefore, the reduced BDNF levels observed in several neurological and peripheral disorders could be linked to bleeding tendencies. Notably, BoNT appears to increase BDNF expression; thus, BoNT-mediated mechanisms influencing platelet aggregation may be associated with its ability to upregulate BDNF[29,32].

Transglutaminase (factor XIIIa), stabilizes blood clots by cross-linking fibrin strands by catalyzing the formation of an isopeptide bond between glutamine and lysine residues[33]. Correspondingly, previous studies have reported the stimulatory effect of the recombinant light chain of BoNT on transglutaminase activity responsible for the blood clotting event in a dose-dependent manner[34]. Besides, Choi et al[35] reported a reduced expression of kallikrein-a class of serine proteases involved in blood clot lysis and fibrinolysis-in the skin tissues of BoNT/A-treated mice. Consistent with earlier findings by Loza et al[36], this suggests that BoNT treatment may inhibit clot lysis reactions, thereby contributing to its potential hemostatic properties. Considering the facts, the present study supports the notion that the relatively effective and safe dose of BoNT has putative roles in blood clotting events through platelet activation, thus it can be considered an alternative to antihaemorrhagic medications for managing extreme bleeding diseases, accidental injuries, and surgical procedures. Taken together, these findings support the hypothesis that BoNT may exert systemic procoagulant effects through multiple mechanisms, including suppression of ACh-mediated platelet inhibition, modulation of serotonergic and collagen-mediated platelet responses, stimulation of clot-stabilizing factors like transglutaminase, and inhibition of fibrinolytic enzymes. The multifaceted action of BoNT highlights its potential as an adjunctive or alternative therapeutic option for managing bleeding complications, particularly in aging populations, various bleeding diseases, traumatic injuries and during surgeries where coagulation pathways are impaired.

With reference to its therapeutic effect, the efficacy of BoNT is dose-dependent. While minimal effective doses can achieve pronounced clinical benefits, increasing the dose elevates the risk of adverse effects[37]. Therefore, treatment with BoNT is generally initiated at the lowest effective dose, with subsequent adjustments made according to patient response and tolerability. Several studies have indicated that BoNT at a dose of approximately 1 U/Kg BW in humans and experimental animals elicits various therapeutic benefits; hence, we selected this dose as a candidate approach in our study[38,39]. However, it should be noted that the efficacy and safety profile of BoNT may vary across different species[40]. Notably, the therapeutic effects of BoNT are known to extend beyond its classical action on ACh release[41]. Therefore, reports suggesting its influence on BDNF and ACh-related changes require verification in a dedicated experimental setup, ideally employing more relevant experimental models in future studies. Moreover, the limited number of animals and the single dose of BoNT employed in the present study, together with the possible mechanistic outcomes supported by earlier reports, represent limitations. The use of a fixed dose (1 U/Kg BW) may not fully account for possible dose–response variations, inter-individual differences, or species-specific pharmacodynamics. Therefore, future studies need to be conducted with larger experimental cohorts, incorporating multiple dose-based approaches and extended follow-up periods to strengthen the robustness of the outcomes. In addition, translation into the human context requires cautious validation in well-controlled preclinical bleeding models to establish the efficacy, safety, and BoNT-induced downstream pathways involved in physiological regulation. It is noteworthy that, despite these verifiable shortcomings, the present study can be regarded as a preliminary yet important report highlighting the potential effects of BoNT on blood coagulation. Adding to its previously established platelet-modulating capacity, the outcomes of the present study provide a fresh outlook and are expected to serve as a basis for future investigations aimed at elucidating the therapeutic relevance of BoNT in the regulation of hemostasis and in the biology of circulation in health and disease.

CONCLUSION

Severe trauma, internal haemorrhagic episodes, bleeding disorders, and frequent intake of blood thinners like aspirin and warfarin are associated with an increased risk of systemic disabilities and are among the leading causes of death worldwide. Additionally, bleeding disorders such as nose gum bleeding, menorrhagia, spontaneous conjunctival hemorrhage, and hyphema are frequently characterized by impaired platelet function. Elevated levels of ACh observed in aging and various aging-related diseases are known to play a major role in the inhibition of platelet activation. Mitigating the pathogenic events related to the excess levels of ACh may facilitate valid therapeutic management for clinical conditions with bleeding complications. Notably, BoNT, an antagonist of ACh release, has been used in a therapeutic regimen for many human diseases and conclusive experimental reports have revealed that BoNT is a platelet-generating agent. In addition to this, the present study also provides supportive evidence for its role in the platelet activation and blood clotting process in aging experimental animals. Though the antihaemorrhagic action of BoNT might directly be related to the reduction in the levels of ACh, the effects of the BoNT on the expression and activation of the other biochemical determinants responsible for the extrinsic and intrinsic clotting factors might not be excluded. In conclusion, BoNT injection in aging experimental mice mitigates haemorrhagic episodes. Thus, BoNT-mediated molecular and biochemical changes associated with the coagulation process could be translated into a therapeutic regime to manage bleeding disorders and excessive blood loss during surgical procedures. Although a mild dose of BoNT has been known to be relatively safe, according to Food and Drug Administration recommendations, the possible adverse effects associated with BoNT treatment cannot be completely ignored. Therefore, further studies are required for additional experimental validations of its pro coagulation effects and further risk assessment needs to be considered.